Abstract

The Hippo pathway controls tissue growth and tumorigenesis by inhibiting cell proliferation and promoting apoptosis. Recent genetic studies in Drosophila identified Kibra as a novel regulator of Hippo signaling. Human KIBRA has been associated with memory performance and cell migration. However, it is unclear whether or how KIBRA is connected to the Hippo pathway in mammalian cells. Here, we show that KIBRA associates with and activates Lats (large tumor suppressor) 1 and 2 kinases by stimulating their phosphorylation on the hydrophobic motif. KIBRA overexpression stimulates the phosphorylation of Yes-associated protein (YAP), the Hippo pathway effector. Conversely, depletion of KIBRA by RNA interference reduces YAP phosphorylation. Furthermore, KIBRA stabilizes Lats2 by inhibiting its ubiquitination. We also found that KIBRA mRNA is induced by YAP overexpression in both murine and human cells, suggesting the evolutionary conservation of KIBRA as a transcriptional target of the Hippo signaling pathway. Thus, our study revealed a new connection between KIBRA and mammalian Hippo signaling.

Keywords: Cellular Regulation, Oncogene, Serine Threonine Protein Kinase, Signal Transduction, Tumor Suppressor, Hippo Signaling Pathway, KIBRA, YAP

Introduction

Precise coordination of cell proliferation and cell death is essential for animal development and organ regeneration. Recent studies in Drosophila have led to the discovery of the Hippo signaling pathway, which controls organ size, tumorigenesis, and cell contact inhibition by regulating cell proliferation and apoptosis (1–6). The core components of the Hippo pathway Hippo (Hpo),3 Salvador (Sav), Warts (Wts), and Mob as tumor suppressor (Mats) form a kinase cascade to regulate the downstream transcriptional co-activator Yorkie (Yki) (1, 7) and target genes such as cyclin E, Drosophila inhibitor of apoptosis (diap1), and the microRNA bantam (1, 5, 8, 9). Upon activation, the Ste20-like kinase Hpo phosphorylates and activates another serine/threonine kinase Wts (10–12), which in turn phosphorylates and inactivates Yki (7, 13). Adaptor proteins Sav and Mats regulate the kinase complexes (12, 14). In Drosophila, Hpo, Sav, Mats, and Wts function as tumor suppressors. Inactivation of any of these or overexpression of the Yki oncoprotein, results in massive tissue overgrowth characterized by excessive cell proliferation and diminished apoptosis (1).

Components of the Hippo network are highly conserved in mammals (3, 15). Several human orthologs of the Hippo signaling components can rescue the respective Drosophila mutants in vivo (7, 12, 14). Furthermore, a number of the mammalian genes in this emerging signaling pathway have already been associated with cancer. Down-regulation of Lats1 and Lats2 (mammalian orthologs of Wts) by promoter hypermethylation is associated with a biologically aggressive phenotype in breast cancer (16). Moreover, mice lacking Lats1 develop several types of tumors (17). Like its counterpart Yki in Drosophila (7), overexpression of YAP in mouse liver dramatically increases the organ size and eventually induces hepatocellular carcinoma (18, 19). Consistently, tissue-specific ablation of both mammalian Ste20-like kinases 1 and 2 (Mst1 and Mst2, Hpo orthologs) in mouse liver leads to hepatocellular carcinoma, confirming the tumor suppressive function of Mst1 and Mst2 (20–22).

Genetic screens identified Kibra as a regulator of the Hippo pathway (23–25). Kibra contains two WW domains and functions together with tumor suppressors Merlin (Mer) and Expanded (Ex) to regulate the Hippo signaling activity in Drosophila (23–25). In humans, KIBRA expression is enriched in kidney and brain (26) and has been associated with memory performance (27–29) and age-dependent risk of Alzheimer disease (30). KIBRA is phosphorylated by atypical protein kinase C ζ (PKCζ) (31) and has been shown to play a role in cell migration (32, 33). However, whether and how KIBRA is involved in the Hippo signaling pathway in mammalian cells remains to be determined. In this study, we show that KIBRA associates with both Lats1 and Lats2 to regulate the Hippo signaling activity in human cells. Our data reveal a new connection between KIBRA and the mammalian Hippo pathway.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Expression Constructs

The human full-length KIBRA cDNA (isoform 1) has been described previously (25). We used this cDNA as a PCR template to clone KIBRA into pcDNA3.1/FLAG (Invitrogen) vector or pcDNA3.1/3xMyc (Invitrogen) to generate N-terminal FLAG-tagged or Myc-tagged KIBRA, respectively. To make N-terminal HA-tagged KIBRA, we first inserted an HA tag into pcDNA3.1+ (Invitrogen) with HindIII and BamHI digestion. The resulting vector, pcDNA3.1+HA, was then used to clone KIBRA PCR products. Deletion constructs were made by PCR and verified by sequencing and restriction enzyme digestion. Point mutations were generated by the QuikChange Site-directed PCR mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and verified by sequencing. Expression constructs Myc-WW45, FLAG-Mst1, FLAG-Mst2, Myc-Lats1, and Lats1-KD, Myc-Lats2, and Lats2-KD have been described previously (19, 34). GFP-YAP was from Addgene.

Cell Lines and Transfection

HEK293T, HEK293GP, and MDA-MB-231 (a breast adenocarcinoma cell line) cell lines were maintained in DMEM (high glucose) containing 10% FBS and l-glutamine plus 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Human pancreatic Nestin-expressing (HPNE) cells and HPNE cells expressing YAP or empty vector were maintained and established as described (19, 35). All of the transient overexpression transfections were performed using Attractene (Qiagen) following the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were harvested at 2 days post-transfection. RNA interference was performed using HiPerFect (Qiagen). For DNA and siRNA co-transfection, Attractene reagents were used. siRNA oligonucleotides were purchased from Dharmacom and GenePharma. MG132 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was dissolved in DMSO at 10 mm. Okadaic acid (from Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was dissolved in methanol at 1 mm. Cycloheximide was purchased from Research Products International Corp. and dissolved in 96% ethanol at 20 mg/ml. All other chemicals were either from Sigma or Thermo Fisher.

Retrovirus Packaging and Infection

To generate shRNA against human KIBRA, oligonucleotides were synthesized (target sequences were as follows: 5′-GGTTGGAGATTACTTCATA-3′ and 5′-AACATATGCTGAAGGATTA-3′) and cloned into pSuper-Retro-puro vector following the company's instructions (Oligoengine). The resulting plasmid was co-transfected with a construct expressing VSV-G gene into the virus packaging cell line HEK293GP to produce retrovirus expressing shRNA against KIBRA. The obtained retroviral supernatant was further filtered and used to infect the MDA-MB-231 cells with polybrene (Millipore) at final concentration 10 μg/ml. The following day, virus supernatant was replaced with fresh growth medium. The transduced cells were then selected with 1 μg/ml of puromycin (at 48 h post-infection) to establish stably expressing KIBRA shRNA cell lines. To make the KIBRA siRNA resistant construct, the corresponding sequence (KIBRA siRNA 1) was changed into 5′-GGTcGGcGAcTAtTTCATA-3′ by PCR mutagenesis. The resulting KIBRA cDNA was cloned into MaRXIV vector and used to infect the MDA-MB-231 KIBRA RNAi 1 cell line and selected with G418 (600 μg/ml) for 7 days. To establish the KIBRA overexpressing stable cell line, KIBRA was cloned into MaRXIV-puro-FLAG vector, and virus packaging and infection were done as described above.

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blot Analysis

At 48 h after transfection, cells were lysed in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (150 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mm PMSF with protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science), and phosphatase inhibitors (10 mm pyrophosphate, 10 mm β-glycerophosphate, 1.5 mm sodium orthovanadate, and 25 mm sodium fluoride). Proteins were immunoprecipitated with appropriate antibodies and Sepharose 4 Fast Flow Protein G beads (GE Healthcare). The proteins were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore). HRP-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG were from Pierce. ECL and SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent substrate kits (Pierce) were used as HRP substrates.

Antibodies

Anti-KIBRA antisera were raised in rabbits against the synthetic peptide sequence, SAQERYRLEEPGTEGKQ, corresponding to amino acids 584–600 of the human KIBRA protein, conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (GenScript). The obtained antisera were further purified on a peptide affinity column. Mouse monoclonal antibodies against FLAG, HA, and Myc were from Sigma-Aldrich. Anti-β-actin and anti-GFP antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-YAP, anti-phospho-Ser127 YAP, anti-phospho-Thr183 Mst1/Thr180 Mst2, and anti-phospho-Thr1079 Lats1 were from Cell Signaling. Anti-Lats1, anti-Lats2, anti-Mst1, and anti-Mst2 antibodies were from Bethyl Laboratories. Anti-Merlin antibodies were from Sigma.

Quantitative Real-time PCR

Total cellular RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent following the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed with a Titan one-tube RT-PCR kit following the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Applied Science). RNA was reverse transcribed with oligo(dT) primers at 42 °C for 50 min using the Superscript III First Strand System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen). For real-time quantitative PCR, 1 μl of the RT reaction was amplified using the SYBR Green Master Mix (Bio-Rad) in a total volume of 25 μl on a 7300 Real-time PCR System (Bio-Rad) with 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, annealing at 61 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. Real-time quantitative PCR was done in triplicate, using GAPDH as a housekeeping control. Relative fold differences in expression of KIBRA in control and YAP-overexpressing HPNE cells were determined using the 2-ΔΔCt method. Primer sequences were as follows: ctccgaggccagagctgtaaggaac (human KIBRA, forward) and ctagaggacttgtgactcagtac (human KIBRA, reverse); gcggccttcctccgtcaagtcc (mouse KIBRA, forward) and gatgttcatccgaggccgggtg (mouse KIBRA, reverse); gatgacatcaagaaggtggtgaag (human GAPDH, forward) and tccttggaggccatgtgggccat (human GAPDH, reverse); and ggaaagctgtggcgtgatggc (mouse GAPDH, forward) and gcctgcttcaccaccttcttg (mouse GAPDH, reverse).

RESULTS

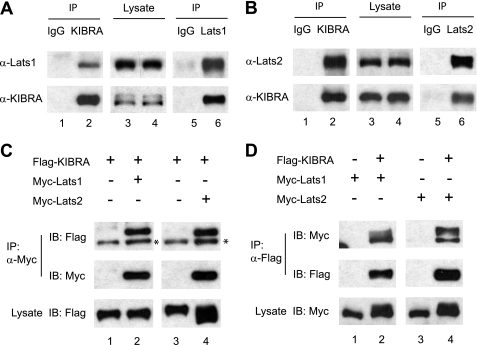

KIBRA Associates with Lats1 and Lats2

To further characterize the function of KIBRA and to explore the relationship between KIBRA and the Hippo signaling in mammalian cells, we generated an anti-KIBRA antibody and performed immunoprecipitations on lysates of HEK293T cells. As expected, KIBRA interacts with endogenous Merlin (supplemental Fig. 1). We found that KIBRA also strongly associates with Lats1 and Lats2. Fig. 1, A and B, showed that immunoprecipitation of KIBRA but not mock immunoprecipitation with IgG control co-precipitates both endogenous Lats1 and Lats2 and vice versa. These interactions were also confirmed by co-transfection of FLAG-tagged KIBRA and Myc-tagged Lats1 and Lats2 (Fig. 1, C and D).

FIGURE 1.

KIBRA associates with Lats1 and Lats2 in human cells. KIBRA proteins were immunoprecipitated (IP) from HEK293T cells by an antibody against human KIBRA (normal rabbit IgG included as controls). The immunoprecipitates were subsequently probed with anti-Lats1 (A) or anti-Lats2 (B) antibodies. A fraction of total cell lysates was also probed with the indicated antibodies to determine the expression levels. Similar immunoprecipitations were done with anti-Lats1 (A) or anti-Lats2 (B) antibodies, and KIBRA protein was detected in both Lats1- and Lats2-IP, but not in control IP. C and D, FLAG-tagged KIBRA and Myc-tagged Lats1 or Lats2 were transfected into HEK293T cells as indicated. At 48 h after transfection, cells were lysed, and proteins were immunoprecipitated using antibodies against the indicated epitope tags. Immunoprecipitated products were subjected to Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies to confirm the presence of appropriate proteins. *, a nonspecific signal. A fraction of total cell lysate was also probed with the indicated antibodies to confirm expression before IP. IB, immunoblot.

WW Domains Are Required for KIBRA to Interact with Lats2

To map the interaction domains, we generated series of FLAG-tagged KIBRA constructs with different deletions at the N terminus. When these constructs were transfected and immunoprecipitated by FLAG antibody from HEK293T cell lysates, we found that deletion of the first 100 amino acids of KIBRA abolished the interaction between KIBRA and Lats2 (Fig. 2A; data not shown), suggesting that KIBRA binds to Lats2 through its N-terminal 100 amino acids.

FIGURE 2.

The WW domains of KIBRA are required for its binding to Lats2. A, schematic diagram of various KIBRA constructs. Boxed 1 and 2 represent the first (amino acids 7–39) and the second (amino acids 54–86) WW domain, respectively. C2, C2-like domain; ΔN100, N-terminal 100-amino acid deletion; W1*, the first WW domain mutant (W34A/P37A); W2*, the second WW domain mutant (P84A); W*W*, KIBRA with mutations at both WW domains (W34A/P37A and P84A); ΔWW, amino acids 1–86 deletion. B, FLAG-tagged KIBRA constructs were transfected into HEK293T cells as indicated. At 48 h after transfection, cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody. Immunoprecipitated products were subjected to Western blot with Lats2 antibody to check the presence of endogenous Lats2. C, HEK293T cells were co-transfected with the indicated DNAs. IPs and Western blots were done as in B. D, schematic diagram of Lats2 constructs. Both the PPPY motif and the kinase domains are shown. E, Myc-tagged KIBRA and FLAG-tagged Lats2 (WT and PY mutant) were transfected into HEK293T cells as indicated. At 48 h after transfection, cells were lysed, immunoprecipitated, and subjected to Western blot analysis with indicated antibodies to check the presence of the appropriate proteins. F, FLAG-tagged KIBRA was co-transfected with Myc-tagged Lats2 wild-type or mutant constructs as indicated. Forty-eight hours post-transfection, cells were lysed, and proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc and subjected to Western blotting to probe for FLAG-tagged KIBRA. IB, immunoblot.

KIBRA contains two WW domains in its N terminus (amino acids 7–39 for WW1 and amino acids 54–86 for WW2, Fig. 2A) (26). We made additional mutations within this region (Fig. 2A) and tested their ability to associate with Lats2. A KIBRA protein mutant containing mutations in both WW domains (W34A/P37A and P84A) largely impaired but did not abolish the interaction between KIBRA and Lats2 (Fig. 2B). A KIBRA mutant with changes in either one of the WW domains (W34A/P37A or P84A) could co-immunoprecipitate with Lats2 as efficiently as WT KIBRA (data not shown). Similarly, in cultured Drosophila cells, a P86A mutation in the first WW domain of Kibra does not affect its interaction with Wts (24); however, the effect of mutations in both WW domains on the interaction between Kibra and Wts has not been determined. Notably, KIBRA lacking the N-terminal 86 amino acids (ΔWW) did not associate with Lats2 (Fig. 2, A–C). Interestingly, the same domain is also required for binding to Lats1 (supplemental Fig. 2). This finding indicates that the intact WW domains are required for KIBRA to interact with Lats1/2 or that other regions (e.g. the first six amino acids before the first WW domain or amino acids 40–53 between the two WW domains) are also involved in binding.

WW domains are predicted to bind to PPxY motifs (36). Lats2 contains a single PPxY motif (515PPPY518) (Fig. 2D). Reciprocally, a Lats2 protein mutated in its PPxY motif (Y518A) partially but not completely lost interaction with KIBRA (Fig. 2E), further implying that another region besides the PPxY motif in Lats2 is involved in associating with KIBRA. Indeed, further deletion tests revealed that amino acids 667–788 (in the Lats2 kinase domain) are required for interaction with KIBRA (Fig. 2, D and F). Thus, the binding between KIBRA and Lats2 requires the N-terminal 86 amino acids of KIBRA and the PPPY motif and amino acids 667–788 in Lats2.

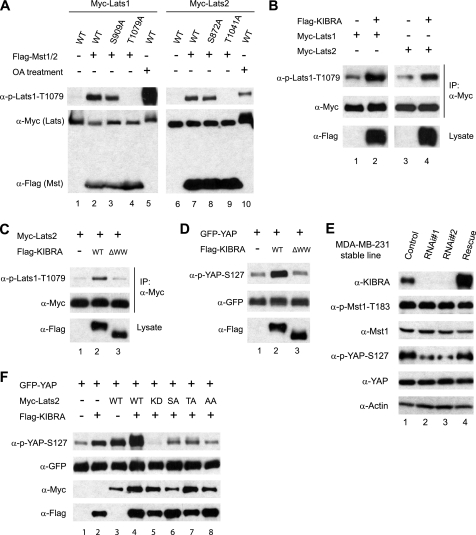

KIBRA Stimulates Lats1 and Lats2 Phosphorylation

Lats1 and Lats2 are serine/threonine protein kinases. Phosphorylation of both an autophosphorylation site (Ser909 for Lats1 and Ser872 for Lats2) and a site in the hydrophobic motif (Thr1079 in Lats1 and Thr1041 in Lats2) is required for their kinase activity (34). The association between KIBRA and Lats1 and Lats2 prompted us to investigate whether KIBRA can promote Lats1/2 kinase activity. We made use of a phosphospecific antibody against the hydrophobic site. The specificity of the antibody is shown in Fig. 3A. Co-transfection of Mst1/2 substantially induced Thr1079/Thr1041 phosphorylation, which was abolished by a Lats1 T1079A mutation or a Lats2 T1041A mutation (Fig. 3A, lanes 4 and 9). As positive controls, okadaic acid treatment stimulated phosphorylation on Thr1079/Thr1041 of Lats1/2 (Fig. 3A, lanes 5 and 10). KIBRA overexpression promoted hydrophobic motif phosphorylation on both Lats1 and Lats2 (Fig. 3B), which is consistent with a previous report wherein a phosphospecific antibody against the Drosophila Wts hydrophobic motif was used (25). Therefore, KIBRA promotes Lats1 and Lats2 kinase activity by stimulating phosphorylation on their hydrophobic sites. Interestingly, the KIBRA protein with its WW domains deleted (ΔWW) is virtually unable to promote the phosphorylation of Lats2, suggesting that the association with Lats2 protein is required for KIBRA to activate the kinase (Fig. 3C).

FIGURE 3.

KIBRA regulates Lats and YAP phosphorylation. A, HEK293T cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids. Cells were treated with or without okadaic acid (OA, 1 μm) for 30 min at 48 h post-transfection, and lysates were probed with anti-phospho-Thr1079 (Thr1041 of Lats2) of Lats1. The membrane was stripped and reprobed with anti-Myc and FLAG antibodies to detect the Lats1/2 and Mst1/2 expression levels, respectively. B, KIBRA promotes both Lats1 and Lats2 phosphorylation. Myc-tagged Lats1 or Lats2 were transfected with empty vector or FLAG-tagged KIBRA, and cellular proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc antibody. Samples were then probed with phospho-specific antibody against Lats1 Thr1079. A portion of total cell lysates was probed with an anti-FLAG antibody to show KIBRA expression. C, Myc-tagged Lats2 was co-transfected with empty vector or FLAG-tagged KIBRA or KIBRA mutants as indicated. IP and Western blotting were done as in B. D, GFP-YAP was transfected with FLAG-KIBRA or its derivatives into HEK293T cells. Total cell lysates were probed with indicated antibodies. ΔWW indicates FLAG-KIBRA with N-terminal amino acids 1–86 deleted. E, MDA-MB-231 cell lines stably expressing control shRNA or shRNA targeting human KIBRA were established (see “Experimental Procedures”). The pooled rescue (Rescue) cells were made by infection of a KIBRA construct resistant to KIBRA RNAi 1 (see “Experimental Procedures”). Lysates from these cell lines were subjected to Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies. F, HEK293T cells were transfected with indicated DNA constructs. Lysates were made at 48 h post-transfection and probed with indicated antibodies. KD, kinase-dead form (K697R); SA, S872A mutant; TA, T1041A mutant; AA, Lats2 with both S872A and T1041A mutations.

KIBRA Regulates YAP Phosphorylation

YAP is a critical substrate of Lats1 and Lats2 kinases (37, 38). Lats1/2 inactivates YAP by phosphorylating serine 127 of YAP (19, 37, 38). We therefore investigated the ability of KIBRA to stimulate YAP Ser127 phosphorylation. Indeed, overexpression of KIBRA resulted in a significant increase of YAP Ser127 phosphorylation (Fig. 3D). As expected, KIBRA with its WW domains deleted was not able to promote YAP Ser127 phosphorylation (Fig. 3D). However, mutation of neither the first WW domain nor the second WW domain alone affected the ability of KIBRA to promote YAP phosphorylation (supplemental Fig. 3). Consistent with our overexpression results, stable knockdown of KIBRA markedly reduced the endogenous phospho-Ser127 level of YAP in MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 3E). Importantly, this effect was largely rescued by expressing siRNA-resistant KIBRA (Fig. 3E). From these observations, we speculate that KIBRA promotes YAP Ser127 phosphorylation by activating Lats1 and Lats2 kinases. To further test this hypothesis, we co-transfected KIBRA with WT Lats2 or various Lats2 mutants. As shown in Fig. 3F, co-transfection of Lats2-KD (K697R mutant, kinase-inactive form) markedly blocked YAP Ser127 phosphorylation stimulated by KIBRA (compare lane 5 with lanes 2–4). Nonphosphorylatable mutant forms (Lats2 S872A or T1041A) partially blocked phosphorylation, as compared with Lats2-KD (Fig. 3F). Thus, our data are consistent with a model in which KIBRA regulates YAP phosphorylation through Lats kinases.

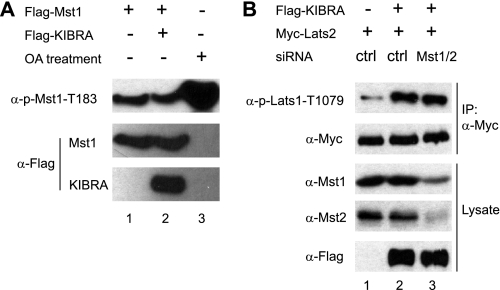

Mst1/2 Are Dispensable for KIBRA to Regulate Phosphorylation of Lats2

Lats1 and Lats2 are phosphorylated and activated by upstream Mst kinases (Fig. 3A, 34). Furthermore, epistatic studies in Drosophila have placed Kibra upstream of Hpo, which is the ortholog of mammalian Mst1/2 (23–25). Therefore, we speculated KIBRA could also activate Mst1/2. Surprisingly, the activity of Mst1/2 revealed by a phosphospecific antibody against the autophosphorylation sites (Thr183 in Mst1 and Thr180 in Mst2) is not affected in KIBRA-knockdown MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 3E). Similarly, overexpression of KIBRA did not affect the phospho-level of Mst1/2 (Fig. 4A). We further showed that KIBRA could stimulate Lats2 phosphorylation with Mst1 and Mst2 knockdown (Fig. 4B). Our data suggest, at least in the cells we tested, a new mechanism exists through which KIBRA regulates Lats1/2 and YAP phosphorylation independent of Mst1/2 kinases.

FIGURE 4.

Mst1/2 are dispensable for KIBRA to stimulate the phosphorylation of Lats2. A, FLAG-tagged Mst1 or empty vector was co-transfected with or without FLAG-KIBRA into HEK293T cells. At 48 h after transfection, cells were treated with (lane 3) or without okadaic acid (OA; lanes 1 and 2) for 1 h. Total cell lysates were probed with anti-p-Mst1-Thr183, and the membrane was stripped and reprobed with FLAG antibody. B, control siRNA or siRNA against Mst1 and Mst2 were co-transfected with Myc-tagged Lats2 and FLAG-tagged KIBRA as indicated. IP and Western blotting were done as in Fig. 3.

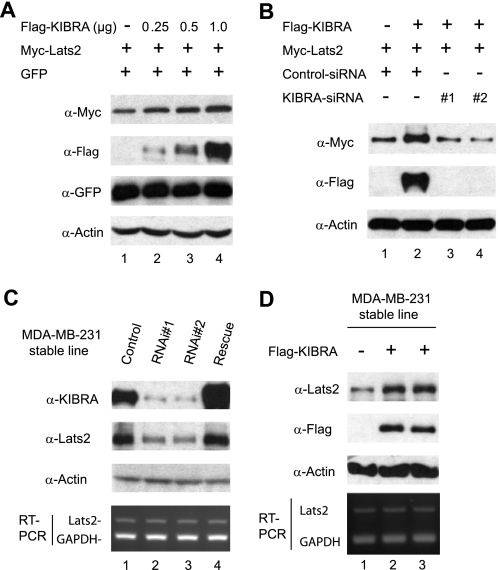

KIBRA Up-regulates Lats2 Protein Level

In the course of these experiments, we noticed that Lats2 protein levels were increased in the presence of KIBRA. To examine whether KIBRA affects Lats2 protein abundance, we transfected Myc-tagged Lats2 with increasing amounts of FLAG-tagged KIBRA. Co-expression of KIBRA resulted in an increase of Lats2 levels (Fig. 5A). To exclude the possibility that this is an artifact due to transfection efficiency, we included the same amount of a GFP construct in all transfections. The expression level of GFP was not significantly changed by KIBRA co-expression, suggesting KIBRA specifically up-regulates Lats2 protein level (Fig. 5A). To further confirm the specificity, we co-transfected Lats2 and KIBRA with control siRNA (scrambled sequence) or siRNA against KIBRA. FLAG-tagged KIBRA was effectively knocked down by co-transfection of KIBRA siRNA but not scrambled siRNA, and this resulted in a marked decrease in Lats2 protein level (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Effects of KIBRA expression on Lats2 protein levels. A, HEK293T cells were transfected with Myc-tagged Lats2 and pEGFP-C1(GFP) with or without increasing amounts of FLAG-tagged KIBRA. At 48 h after transfection, total cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis to detect the Lats2 and GFP protein levels. The lysates were also probed with anti-FLAG to detect the KIBRA expression, and with anti-β-actin antibody to show equal loading. B, HEK293T cells were transfected with Myc-Lats2 with (lanes 2–4) or without (lane 1) FLAG-KIBRA together either with siRNA oligonucleotides targeting the human KIBRA sequence (lanes 3 and 4) or with a scrambled oligonucleotide (lanes 1 and 2). At 48 h post-transfection, total cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis using indicated antibodies. C, MDA-MB-231 cell lines stably expressing control shRNA or shRNA targeting human KIBRA were established (see “Experimental Procedures”). The rescue cells were generated as in Fig. 3. Total protein lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-Lats2 and anti-KIBRA antibodies to detect the Lats2 and KIBRA protein levels, respectively. Two pooled lines are shown. Semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed with primers amplifying Lats2 and GAPDH (control) (bottom panel). D, MDA-MB-231 cell lines stably expressing control vector or FLAG-KIBRA were established (see “Experimental Procedures”). Total protein lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-Lats2 antibody to detect the endogenous Lats2 protein level and with anti-FLAG antibody to confirm KIBRA expression (two separately generated lines are shown). Total RNA was also isolated from these cell lines and semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed with primers amplifying Lats2 and GAPDH (control) (bottom panel).

To further confirm the importance of KIBRA in controlling Lats2 levels, we measured the steady-state levels of Lats2 in KIBRA knockdown cells. Fig. 5C shows that stable reduction of KIBRA in MDA-MB-231 cells caused a significant decrease in endogenous Lats2. Importantly, addition of an siRNA-resistant form of KIBRA largely restored the Lats2 level, confirming the specificity of KIBRA knockdown (Fig. 5C). Accordingly, endogenous Lats2 levels were increased when KIBRA was overexpressed in MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 5D). Thus, our data suggest KIBRA controls the Lats2 protein level, and this is not likely regulated at the transcriptional level since Lats2 mRNA levels are not affected in KIBRA overexpression or knockdown cells (Fig. 5, C and D, bottom panels).

KIBRA Prolongs Lats2 Half-life

The observed correlation between KIBRA expression and Lats2 abundance prompted us to test whether KIBRA prevents Lats2 from degradation. To investigate this possibility, we first measured Lats2 half-life in the presence or absence of overexpressed KIBRA. Forty-eight hours post-transfection, cells were treated with cycloheximide to inhibit protein synthesis. In the presence of overexpressed KIBRA, the half-life of transfected Myc-tagged Lats2 was strikingly prolonged (Fig. 6A). We also measured the half-life of endogenous Lats2 with or without KIBRA knockdown. In agreement with our overexpression data, reduction of KIBRA by RNA interference resulted in more rapid degradation of endogenous Lats2 protein (Fig. 6B).

FIGURE 6.

KIBRA prolongs Lats2 half-life. A, HEK293T cells were transfected with Myc-Lats2, together with either empty vector or FLAG-KIBRA, as indicated. At 48 h post-transfection, cells were treated with 20 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) for different time points as indicated. Total protein lysates were subjected to Western blot with indicated antibodies. The amounts of Lats2 were quantified by densitometry. The ratio between Lats2 and actin at the zero time point was arbitrarily set to 1. B, MDA-MB-231 cell lines stably expressing control shRNA or shRNA targeting human KIBRA were treated with 20 μg/ml cycloheximide for different time points. Total protein lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-Lats2 and anti-KIBRA antibodies to detect the endogenous Lats2 and KIBRA protein levels, respectively. The same blot was also probed with an anti-β-actin antibody to show equal loading. The relative Lats2 levels were determined as in A. C, HEK293T cells were transfected with Myc-Lats2, and the cells were treated with DMSO or 25 μm MG132 for 4 and 8 h, respectively. Cell lysates were harvested and analyzed by Western blot with the indicated antibodies. D, HEK293T cells were transfected with Myc-tagged Lats2, FLAG-tagged Ub, and HA-tagged KIBRA as indicated. At 48 h post-transfection, cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with an anti-Myc antibody. Co-precipitating proteins were detected with anti-FLAG antibody. A portion of total cell lysates was also probed with anti-HA or anti-FLAG antibodies to check the expression levels of KIBRA and ubiquitin, respectively. E, control siRNA and siRNA against KIBRA (two independent oligonucleotides) were co-transfected as indicated. IP and Western blotting were done as in D.

Like many other proteins, Lats2 is degraded through the proteasomal pathway because a proteasome inhibitor MG132 greatly increased Lats2 protein levels (Fig. 6C). Ubiquitination of target proteins is very common prior to proteasomal degradation. To determine whether Lats2 is ubiquitylated, Myc-Lats2 was co-transfected with FLAG-tagged ubiquitin (Ub) in HEK293T cells. As expected, FLAG-Ub was detected in Myc-Lats2 immunoprecipitates, consistent with the possibility that Lats2 is ubiquitylated in vivo (Fig. 6D, lane 2). Interestingly, addition of KIBRA partially inhibited Lats2 ubiquitination (Fig. 6D, lane 3). Accordingly, KIBRA knockdown increased Lats2 ubiquitination when Lats2 was co-expressed with Ub (Fig. 6E). These observations indicate that KIBRA prevents Lats2 from proteasomal degradation by at least partially inhibiting Lats2 ubiquitination.

KIBRA Is a Transcriptional Target of Hippo Signaling

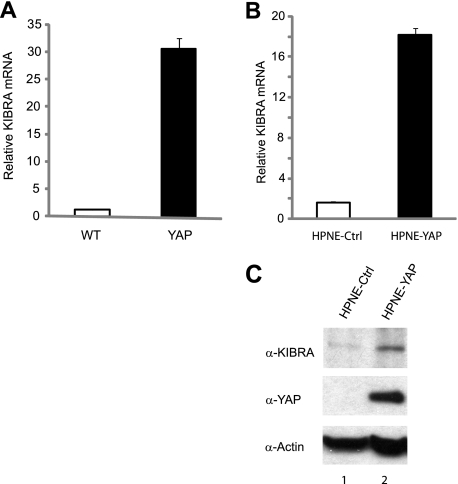

Several upstream regulators of the Hippo pathway, including Mer and Ex, are also transcriptional targets of Hippo signaling in Drosophila (39). A recent study of Drosophila demonstrated that Kibra is also a transcriptional target of Hippo signaling (24). It is not known whether this is also the case in mammalian cells, but our finding that KIBRA mRNA levels were up-regulated in YAP transgenic liver suggests that it may be (19). Quantitative RT-PCR confirmed that KIBRA mRNA levels were increased ∼30-fold in YAP-overexpressing mouse livers compared with the WT (Fig. 7A). We next tested whether an increase in YAP also elevates KIBRA in human cells. To this end, we established an HPNE cell line stably expressing YAP. Interestingly, KIBRA mRNA levels were significantly up-regulated in YAP-transfected HPNE cells (Fig. 7B). As expected, KIBRA protein levels were also elevated in cells stably overexpressing YAP (Fig. 7C). These observations suggest that KIBRA is an evolutionarily conserved transcriptional target of the Hippo pathway.

FIGURE 7.

KIBRA is a transcriptional target of the Hippo pathway. A, YAP overexpression induces KIBRA expression in mouse livers. Total RNA was isolated from WT (n = 3) and YAP-transgenic (n = 3, 2 weeks of YAP induction) mouse livers and subjected to quantitative RT-PCR. B, YAP induces KIBRA expression in human cells. Total RNA was isolated from HPNE cells stably expressing empty vector or YAP and subjected to quantitative RT-PCR. C, total protein lysates from the cells in B were subjected to Western blot analysis with anti-KIBRA, anti-YAP, and anti-β-actin antibodies. Error bars in A and B represent S.D. from three independent experiments. Ctrl, control.

DISCUSSION

Kibra was recently identified as a regulator of the Hippo pathway by three independent groups (23–25). In Drosophila, loss of Kibra function causes increased proliferation and reduced apoptosis and regulates Hippo signaling targets, which are typical phenotypes of loss-of-function of Hippo components. Human KIBRA has been reported to interact with several partners and involved in different cellular functions (40); however, the signaling pathway through which it functions has remained elusive. Our study has revealed a new connection between KIBRA and the Hippo pathway in human cells, suggesting that KIBRA may also function through the Hippo pathway in mammals and further implying the existence of a potential role for KIBRA in regulating cell proliferation and cell death.

Kibra functions upstream of Hpo and associates with Mer and Ex to regulate Hippo signaling in Drosophila (23–25). The association between KIBRA and neurofibromatosis type 2/Mer seems to be conserved in human cells (24, 41). In this study, we show that KIBRA also binds to Lats1 and Lats2 and that binding is required for KIBRA to regulate Lats and YAP activity. However, we could not detect a significant change of Mst1/2 activity upon KIBRA overexpression or depletion. These observations suggest that KIBRA, at least in certain human cells, can regulate Hippo signaling activity in both Mst1/2-dependent (through association with neurofibromatosis type 2/Mer) and Mst1/2-independent (directly through Lats1/2) manners. This dual activity may also be the case in Drosophila as Kibra associates with Wts to regulate Yki phosphorylation in cultured Drosophila cells (24). Both Mst1 and Mst2 knock-out mice have been generated recently (20–22); thus, Mst1- and Mst2-negative mouse embryonic fibroblast cells will provide an excellent system to further test this hypothesis.

Our data suggest that KIBRA regulates Lats2 by a 2-fold mechanism. First, KIBRA affects Lats2 kinase activity by modulating the phosphorylation of the hydrophobic motif site (Thr1041), and binding is required for regulating the phosphorylation. In addition, KIBRA also stabilizes Lats2 protein. Surprisingly, the WW domains are not involved for the latter function because KIBRA with deleted WW domains can still stabilize Lats2 (data not shown). The precise mechanism by which KIBRA stabilizes Lats2 is currently unclear. Identification of the specific E3 ligase involved in Lats2 ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation will be highly informative.

Several components of the Hippo signaling, including Mer and Ex, are also its transcriptional targets in Drosophila (39). However, none of these genes has been shown to be targets of Hippo pathway in mammalian cells. The identification of KIBRA as a transcriptional target of both the mammalian (Fig. 7, this study) and Drosophila Hippo pathway (24) provides the first evidence suggesting the existence of an evolutionarily conserved negative feedback loop. How KIBRA mRNA is induced by YAP is not yet known. In mammalian cells, the Hippo/YAP signaling pathway regulates downstream targets mainly through the transcriptional factors TEAD1–4 (42). However, we could not detect TEAD binding sites in the KIBRA promoter region (data not shown), suggesting that YAP may function together with an undiscovered transcriptional factor to regulate KIBRA transcription.

The Hippo pathway plays a pivotal role in organ size control and tumorigenesis by regulating cell proliferation and apoptosis. Recent studies in Drosophila identified PKCζ and Crumbs as novel regulators of the Hippo signaling pathway(43–45), providing a mechanism through which these cell polarity regulators control cell proliferation and survival. There are two cell polarity complexes, the aPKC-PAR3-PAR6 (PAR for partitioning defective) and the Pals1-PATJ-Crb complex (Pals1 for protein associated with Lin7–1; PATJ for Pals1-associated tight junction protein; and Crb for Crumbs3) (46, 47). The biochemical association linking these proteins to the core Hippo signaling is still missing. Interestingly, it was shown that KIBRA interacts with both the apical polarity regulator PKCζ (31) and PATJ (32). Whether KIBRA functions as such a link is an uninvestigated but intriguing possibility. It will be interesting to determine whether KIBRA plays a role in the maintenance of cell polarity and the establishment of tight junction of human epithelial cells.

KIBRA interacts with the postsynaptic protein dendrin and synaptopodin via its WW domains and is thought to play a role in synaptic plasticity and cell migration of podocytes (26, 32). Our data reveal that the WW domains are also required for KIBRA to interact with Lats2 and to regulate YAP phosphorylation. How these interactions are coordinated and whether these interactions are cell type-specific are unknown. Of note, in cultured Drosophila cells, a truncated Kibra protein lacking the WW domains interacts more efficiently with Mer, and it was suggested that the physical interaction between Kibra and Mer is modulated by binding of other factors to the WW domains of Kibra (23). It will be interesting to examine whether Lats1/2 are some of the “other factors.” In addition, it remains unclear whether dendrin and synaptopodin control synaptic plasticity and podocyte migration through the Hippo signaling pathway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Duojia Pan (Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine) for various reagents, Dr. Hamid Band (University of Nebraska Medical Center) for FLAG-Ub DNA construct, and Dr. Jing (Jenny) Wang (University of Nebraska Medical Center) for reagents and suggestions on retrovirus packaging. We also thank Drs. Robert Lewis, Joyce Solheim, and Keith Johnson for critical reading and comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant 5P20-RR018759-07 from the National Center for Research Resources and a grant from the Nebraska Department of Health and Human Services (to J. D.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–3.

- Hpo

- Hippo

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- Lats

- large tumor suppressor

- Mst

- mammalian Ste20-like

- KD

- kinase-dead

- Ub

- ubiquitin

- YAP

- yes-associated protein

- Sav

- Salvador

- Wts

- Warts

- Mer

- Merlin

- Ex

- Expanded

- Mats

- Mob as tumor suppressor

- Yki

- Yorkie

- HPNE

- human pancreatic Nestin-expressing.

REFERENCES

- 1. Pan D. (2010) Dev. Cell 19, 491–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhao B., Lei Q. Y., Guan K. L. (2008) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 20, 638–646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhao B., Li L., Lei Q., Guan K. L. (2010) Genes Dev. 24, 862–874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kango-Singh M., Singh A. (2009) Dev. Dyn. 238, 1627–1637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Saucedo L. J., Edgar B. A. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 613–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Harvey K., Tapon N. (2007) Nat. Rev. Cancer. 7, 182–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Huang J., Wu S., Barrera J., Matthews K., Pan D. (2005) Cell 122, 421–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Edgar B. A. (2006) Cell 124, 267–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reddy B. V., Irvine K. D. (2008) Development 135, 2827–2838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harvey K. F., Pfleger C. M., Hariharan I. K. (2003) Cell 114, 457–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pantalacci S., Tapon N., Léopold P. (2003) Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 921–927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wu S., Huang J., Dong J., Pan D. (2003) Cell 114, 445–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Oh H., Irvine K. D. (2008) Development 135, 1081–1088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lai Z. C., Wei X., Shimizu T., Ramos E., Rohrbaugh M., Nikolaidis N., Ho L. L., Li Y. (2005) Cell 120, 675–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zeng Q., Hong W. (2008) Cancer Cell. 13, 188–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Takahashi Y., Miyoshi Y., Takahata C., Irahara N., Taguchi T., Tamaki Y., Noguchi S. (2005) Clin. Cancer Res. 11, 1380–1385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. St John M. A., Tao W., Fei X., Fukumoto R., Carcangiu M. L., Brownstein D. G., Parlow A. F., McGrath J., Xu T. (1999) Nat. Genet. 21, 182–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Camargo F. D., Gokhale S., Johnnidis J. B., Fu D., Bell G. W., Jaenisch R., Brummelkamp T. R. (2007) Curr. Biol. 17, 2054–2060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dong J., Feldmann G., Huang J., Wu S., Zhang N., Comerford S. A., Gayyed M. F., Anders R. A., Maitra A., Pan D. (2007) Cell 130, 1120–1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhou D., Conrad C., Xia F., Park J. S., Payer B., Yin Y., Lauwers G. Y., Thasler W., Lee J. T., Avruch J., Bardeesy N. (2009) Cancer Cell. 16, 425–438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lu L., Li Y., Kim S. M., Bossuyt W., Liu P., Qiu Q., Wang Y., Halder G., Finegold M. J., Lee J. S., Johnson R. L. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 1437–1442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Song H., Mak K. K., Topol L., Yun K., Hu J., Garrett L., Chen Y., Park O., Chang J., Simpson R. M., Wang C. Y., Gao B., Jiang J., Yang Y. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 1431–1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Baumgartner R., Poernbacher I., Buser N., Hafen E., Stocker H. (2010) Dev. Cell. 18, 309–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Genevet A., Wehr M. C., Brain R., Thompson B. J., Tapon N. (2010) Dev. Cell. 18, 300–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yu J., Zheng Y., Dong J., Klusza S., Deng W. M., Pan D. (2010) Dev. Cell. 18, 288–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kremerskothen J., Plaas C., Büther K., Finger I., Veltel S., Matanis T., Liedtke T., Barnekow A. (2003) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 300, 862–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Papassotiropoulos A., Stephan D. A., Huentelman M. J., Hoerndli F. J., Craig D. W., Pearson J. V., Huynh K. D., Brunner F., Corneveaux J., Osborne D., Wollmer M. A., Aerni A., Coluccia D., Hänggi J., Mondadori C. R., Buchmann A., Reiman E. M., Caselli R. J., Henke K., de Quervain D. J. (2006) Science 314, 475–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bates T. C., Price J. F., Harris S. E., Marioni R. E., Fowkes F. G., Stewart M. C., Murray G. D., Whalley L. J., Starr J. M., Deary I. J. (2009) Neurosci. Lett. 458, 140–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schaper K., Kolsch H., Popp J., Wagner M., Jessen F. (2008) Neurobiol. Aging 29, 1123–1125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Corneveaux J. J., Liang W. S., Reiman E. M., Webster J. A., Myers A. J., Zismann V. L., Joshipura K. D., Pearson J. V., Hu-Lince D., Craig D. W., Coon K. D., Dunckley T., Bandy D., Lee W., Chen K., Beach T. G., Mastroeni D., Grover A., Ravid R., Sando S. B., Aasly J. O., Heun R., Jessen F., Kölsch H., Rogers J., Hutton M. L., Melquist S., Petersen R. C., Alexander G. E., Caselli R. J., Papassotiropoulos A., Stephan D. A., Huentelman M. J. (2010) Neurobiol. Aging 31, 901–909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Büther K., Plaas C., Barnekow A., Kremerskothen J. (2004) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 317, 703–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Duning K., Schurek E. M., Schlüter M., Bayer M., Reinhardt H. C., Schwab A., Schaefer L., Benzing T., Schermer B., Saleem M. A., Huber T. B., Bachmann S., Kremerskothen J., Weide T., Pavenstädt H. (2008) J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 19, 1891–1903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rosse C., Formstecher E., Boeckeler K., Zhao Y., Kremerskothen J., White M. D., Camonis J. H., Parker P. J. (2009) PLoS. Biol. 7, e1000235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chan E. H., Nousiainen M., Chalamalasetty R. B., Schäfer A., Nigg E. A., Silljé H. H. (2005) Oncogene 24, 2076–2086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lee K. M., Yasuda H., Hollingsworth M. A., Ouellette M. M. (2005) Lab. Invest. 85, 1003–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Einbond A., Sudol M. (1996) FEBS Lett. 384, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhao B., Wei X., Li W., Udan R. S., Yang Q., Kim J., Xie J., Ikenoue T., Yu J., Li L., Zheng P., Ye K., Chinnaiyan A., Halder G., Lai Z. C., Guan K. L. (2007) Genes Dev. 21, 2747–2761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hao Y., Chun A., Cheung K., Rashidi B., Yang X. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 5496–5509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hamaratoglu F., Willecke M., Kango-Singh M., Nolo R., Hyun E., Tao C., Jafar-Nejad H., Halder G. (2006) Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 27–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schneider A., Huentelman M. J., Kremerskothen J., Duning K., Spoelgen R., Nikolich K. (2010) Front. Aging. Neurosci. 2, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhang N., Bai H., David K. K., Dong J., Zheng Y., Cai J., Giovannini M., Liu P., Anders R. A., Pan D. (2010) Dev. Cell. 19, 27–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhao B., Ye X., Yu J., Li L., Li W., Li S., Yu J., Lin J. D., Wang C. Y., Chinnaiyan A. M., Lai Z. C., Guan K. L. (2008) Genes Dev. 22, 1962–1971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Grzeschik N. A., Parsons L. M., Allott M. L., Harvey K. F., Richardson H. E. (2010) Curr. Biol. 20, 573–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Robinson B. S., Huang J., Hong Y., Moberg K. H. (2010) Curr. Biol. 20, 582–590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ling C., Zheng Y., Yin F., Yu J., Huang J., Hong Y., Wu S., Pan D. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 10532–10537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Margolis B., Borg J. P. (2005) J. Cell Sci. 118, 5157–5159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shin K., Fogg V. C., Margolis B. (2006) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 22, 207–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.