Abstract

Most amyloids are pathological, but fragments of Pmel17 form a functional amyloid in vertebrate melanosomes essential for melanin synthesis and deposition. We previously reported that only at the mildly acidic pH (4–5.5) typical of melanosomes, the repeat domain (RPT) of human Pmel17 can form amyloid in vitro. Combined with the known presence of RPT in the melanosome filaments and the requirement of this domain for filament formation, we proposed that RPT may be the core of the amyloid formed in vivo. Although most of Pmel17 is highly conserved across a broad range of vertebrates, the RPT domains vary dramatically, with no apparent homology in some cases. Here, we report that the RPT domains of mouse and zebrafish, as well as a small splice variant of human Pmel17, all form amyloid specifically at mildly acid pH (pH ∼5.0). Protease digestion, mass per unit length measurements, and solid-state NMR experiments suggest that amyloid of the mouse RPT has an in-register parallel β-sheet architecture with two RPT molecules per layer, similar to amyloid of the Aβ peptide. Although there is no sequence conservation between human and zebrafish RPT, amyloid formation at acid pH is conserved.

Keywords: Amyloid, Electron Microscopy (EM), NMR, Protein Assembly, Protein Folding, Protein Structure, Melanosome

Introduction

Amyloid is a filamentous β-sheet-rich protein polymer usually associated with Alzheimer disease, Parkinson disease, type II diabetes, and other pathological conditions, but several functional amyloids have been identified. The external curli fibers of Escherichia coli are involved in biofilm formation and adhesion to host cells (1); the hydrophobin amyloids protect fungal cell surfaces (2), and the [Het-s] prion of Podospora anserina appears to help the host by facilitating heterokaryon incompatibility (3).

Pmel17 is a protein important for melanin synthesis and deposition that forms intralumenal filaments in melanosomes, the endosome/lysosome-like organelle in which melanin synthesis takes place (reviewed in Refs. 4, 5). Pmel17 is made as a transmembrane protein, processed by a series of proteolytic steps and glycosylations and assembled into a filamentous form in stage II melanosomes. There, Pmel17 filaments facilitate melanization, perhaps acting as a template on which melanin is deposited or by adsorbing toxic by-products of the melanin biosynthetic process (reviewed in Ref. 6).

The gene for Pmel17 was first identified by a single gene mouse mutant called Silver, in which the normal black coat color was lost as animals grew and aged (7). The mouse Pmel17 cDNA, mapping at the Silver locus, defined the protein with its single transmembrane region and repeat domain (8). Comparisons of orthologs from a number of vertebrate species have revealed the domain structure shown in supplemental Fig. 1 (6, 9). Human Pmel17 consists of (N- to C-terminal) a signal peptide (residues 1–23 in the human protein), an N-terminal domain, the polycystic kidney disease-like domain (PKD),2 the repeat domain (RPT), the Kringle-like domain (KLD or KRG), the transmembrane domain, and the cytoplasmic C-terminal domain. Most parts of Pmel17 are well aligned across species, with the striking exception of the RPT region, where the mouse RPT (mRPT) has only 50% sequence identity and the zebrafish repeat (zfRPT) domain appears unrelated to that of humans (Fig. 1). What is conserved, however, is the presence of a repeat structure in this domain of every species examined (supplemental Fig. 1).

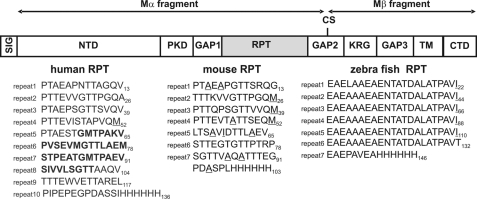

FIGURE 1.

Domains within pre-melanosomal protein (Pmel17). SIG, signal peptide; NTD, N-terminal domain; PKD, polycystic kidney disease-like domain; RPT, repeat domain (see below); KRG, Kringle-like domain; TM, transmembrane domain; CTD, C-terminal domain; GAP1, GAP2, and GAP3, undefined domains. The Kex2/Furin-like cleavage C-terminal to RPT at “CS” that generates Mα and Mβ is necessary for fibril formation. N-Glycosylation and O-glycosylated RPT sites differ among the Pmel17 orthologs and have not been precisely mapped except for the human long form. Sequences of human short RPT (hsRPT), mouse RPT (mRPT), and zebrafish RPT (zfRPT) are shown. The hsRPT domain lacks the 42 amino acids shown in boldface. Underlined residues were used in solid-state NMR experiments.

Detailed and careful cell biological studies by several groups have defined the requirements for transport of Pmel17 to the early melanosomes and for filament formation (10–12). The N-terminal domain and PKD are necessary for proper sorting of Pmel17, but RPT, Kringle-like domain, and C-terminal domain are dispensable for this aspect. RPT is needed for filament formation, although the Kringle-like domain is not. Because the N-terminal domain and PKD are necessary for sorting of Pmel17 into melanosomes, it is difficult to determine whether they are needed for filament formation. Current evidence indicates that a region at the junction of NTR and PKD is indeed involved in filament formation (12). Antibodies specific for RPT or PKD decorate the filaments in melanosomes (13) indicating that at least parts of these regions are part of the filaments. Pmel17 is cleaved several times in the course of melanosome maturation, including a Kex2/Furin-like cut C-terminal to RPT that is necessary for filament formation (14). Glycosylation of Pmel17 appears to be necessary for filament formation in vivo (15), suggesting that attempts to define the amyloid core using recombinant proteins must be interpreted with caution.

Melanosomes, early or late, are acidic compartments (13, 16–19). This acidification is necessary for proper melanin formation, as shown, for example, by the lack of pigmentation of mice with a P (for pink eyed) mutation defective for melanosome acidification (20), and these mutants have disordered melanosome filaments (21).

Of the several human Pmel17 fragments we examined, only RPT (hlRPT) (residues 315–444) formed amyloid (22), and that only at the mildly acid pH typical of melanosomes (22, 23). These filaments are stable at pH 4.0–6.0 but dissolve at pH 7.0, have typical straight unbranched amyloid morphology (like melanosome filaments), are high in β-sheet by electron diffraction and solid-state NMR, and facilitate melanin synthesis in vitro. This RPT fragment shows anomalously slow migration during denaturing gel electrophoresis (22) making it similar to the migration of RPT-containing fragments found in melanosome filaments (11, 24). This suggested that RPT, known to be necessary for filament formation and to be present in the filaments, is the core of the Pmel17 filaments, similar to the prion domains of the yeast prion proteins Ure2p and Sup35p (reviewed in Ref. 25).

Recently, it was found that a PKD fragment also forms amyloid filaments in vitro at neutral pH, suggesting a role for this domain as well in filament formation (24). Other fragments examined under these conditions formed aggregates lacking the typical morphology of amyloid, but nonetheless they were high in β-sheet content.

One test of the role of RPT in amyloid formation is to examine the corresponding region from Pmel17 orthologs. We show here that the dramatically different mouse and zebrafish RPT domains (mRPT and zfRPT) also form amyloid with a similar pH dependence to that previously found for the human Pmel17 RPT fragment. We further find that the small splice variant of human RPT (hsRPT) (26) also forms amyloid in vitro. These results support our view that RPT is in the core of the Pmel17 amyloid.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

hsRPT, mRPT, and zfRPT Protein Expression and Purification

Pmel17 clones for mRPT (accession number BC082555) and zfRPT (accession number BC117628) were purchased as cDNA from Open Biosystems. RPT domains (Fig. 1) with C-terminal His tags were subcloned into pET21a(+) (Novagen) (supplemental Table 1) and expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) RIPL (Stratagene). Shaken cultures (1 liter of Luria Broth) were grown at 37 °C to an A600 = 0.4–0.6 and then induced with 1.0 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside for 4 h. For isotopic labeling, cells were grown in defined amino acid medium as described previously (27). Cells were collected by centrifugation at 4 °C and then resuspended in denaturing buffer (8 m guanidine, 100 mm NaCl, 100 mm K2HPO4, pH 8.0, and 10 mm imidazole) and incubated for 60 min at room temperature with gentle agitation. The generated lysate was spun at 70,000 × g for 45 min. The pellet was discarded, and the supernatant was mixed with nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose (from Qiagen; 5 ml per 1 liter of culture) and incubated at room temperature for 60 min with agitation. The mixed nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid lysate was poured into a column and washed with 10 column volumes of buffer (8 m Gdn-HCl, 100 mm NaCl, 100 mm K2HPO4, pH 8.0, and 20 mm imidazole). The protein was eluted with buffer containing 8 m GuHCl, 100 mm NaCl, 100 mm K2HPO4, pH 8.0, and 250 mm imidazole. RPT aggregates were generated by dialyzing purified protein into 125 mm potassium acetate buffer, pH 5.0, and incubating at room temperature with agitation.

Electron Microscopy

Diluted samples were adsorbed on carbon-coated copper grids, stained with 3% aqueous uranyl acetate, and visualized with an FEI Morgagni transmission electron microscope operating at 80 kV.

Electron Diffraction

A suspension of hsRPT or mRPT fibers (2 mg/ml monomer concentration) was applied to a carbon-coated copper grid and incubated for ∼30 min. Excess liquid was blotted, and the grid was quickly washed with 0.5 mm potassium acetate, pH 5.0, before air drying. Electron diffraction images were collected using an 80-kV electron beam with a 350-mm camera length. Diffraction distances and atomic spacing were calibrated using thallous chloride crystals under identical microscope conditions.

Circular Dichroism Secondary Structure Analysis

RPT fibers (0.1 mg/ml) in 5.0 mm potassium acetate buffer, pH 5.0, or 5.0 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, were analyzed using a Jasco J-715 spectropolarimeter as described previously (28).

Amyloid-specific Dye Assays

Thioflavin T fluorescence was performed using a Photon Technology International QuantaMaster fluorimeter as described previously (29). RPT fibrils were dispensed into a quartz cuvette to a final concentration of 10 μg/ml. The assay was performed in 50 mm buffers, pH 5.0–8.0, and 0.01 mg/ml thioflavin T with constant stirring at room temperature. Excitation was 440 nm, and data were collected at 482 nm. For intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence, RPT fibers (0.1 mg/ml protein) in 50 mm buffers, pH 4.0–9.0, were mixed with constant stirring in a quartz cuvette. Excitation was 280 nm, and data were collected between 310 and 410 nm.

Mass Per Length Measurements

Dark field electron microscopy was used to measure the mass per unit length of unstained mRPT filaments, as described by Chen et al. (30).

Proteinase K Assay

Proteinase K digestion was performed by incubating 2 μg/ml proteinase K with 0.5 mg/ml fibrous hsRPT, mRPT, and zfRPT for 16 h. Reactions were performed in 125 mm potassium acetate buffer, pH 5.0, at room temperature in a total volume of 1.0 ml. The reactions were terminated by the addition of 4% TCA. Samples were lyophilized and resuspended in 5% acetic acid prior to LC-MS analysis.

Solid-state NMR Methods

Dipolar recoupling (PITHIRDS-CT) experiments (31) and one-dimensional spectra using selectively labeled samples were carried out at 9.39 tesla (100.4 MHz 13C NMR frequency) using an InfinityPlus spectrometer (Varian) and magic angle spinning probes (Varian) with 3.2-mm diameter rotors. Measurements were carried out with magic angle spinning at 20 kHz at room temperature, using 1H-13C cross-polarization (32) and two-pulse phase-modulated 1H decoupling (33). In the PITHIRDS-CT experiments, pulsed spin-lock detection was used for improved signal-to-noise ratio (34), except for experiments with [1-13C]Ile and [1-13C]Met-labeled mRPT samples for which two carbonyl peaks were resolved (Fig. 5 and supplemental Fig. 5). Except as indicated, filaments were washed with 0.5 mm potassium acetate buffer, pH 5.0, pelleted at 50,000 × g, and packed by centrifugation into thick-walled rotors. Each PITHIRDS-CT data point is the result of >2048 scans with a 4-s recycle delay.

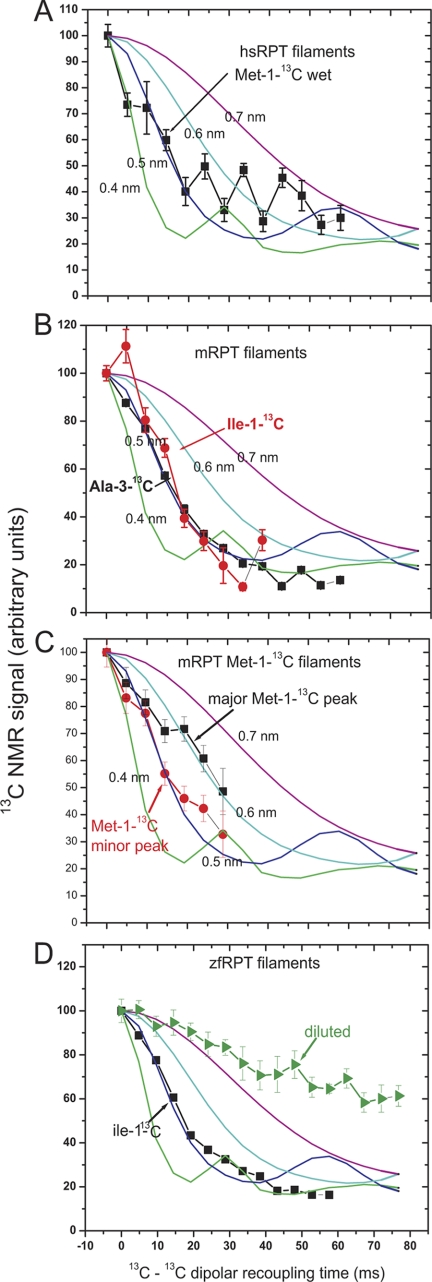

FIGURE 5.

Solid-state NMR 13C-13C dipolar recoupling experiments of 13C-labeled filaments using the PITHIRDS-CT pulse sequence (31). A, wet filaments of hsRPT labeled with [1-13C]Met in 0.5 mm potassium acetate pH 5.0. The data are uncorrected for natural abundance. B, wet mRPT labeled with [1-13C]Ile (1 residue) or [3-13C]Ala (8 residues). C, wet mRPT labeled with [1-13C]Met (3 residues). The two peaks (see Table 1) are plotted separately and no correction for natural abundance 13C is made. D, dry zfRPT labeled with [1-13C]Ile (5 residues).

The raw PITHIRDS-CT data (Sraw) were corrected for the 1.1% natural abundance of 13C, except as otherwise noted. The fraction of natural abundance 13C (fna) is calculated from the total number of carbonyl carbons (for 1-13C-labeled amino acids) or of methyl carbons (for methyl-labeled alanine). Natural abundance 13C atoms are widely spaced, and so their signal (Sna) decays slowly, according to Sna(t) = 100–0.2t, where t is the dipolar recoupling time in milliseconds. The corrected signal (S(t)) is as shown in Equation 1,

|

Two-dimensional Solid-state NMR Experiments

Uniformly 15N,13C-labeled amyloid fibrils were pelleted and packed into a 3.2-mm zerconia rotor for magic angle spinning experiments. The sample was measured by 1H-13C cross-polarization in conjunction with finite pulse radio frequency-driven recoupling (35) or radio frequency-assisted diffusion (36, 37) pulse sequences to detect solid-state NMR signals and correlate 13C resonance frequencies of bonded or spatially close carbons (e.g. in the same amino acid residue). The same fibril sample was examined using the INEPT pulse sequence (38), with MAS at 4 kHz and 1H decoupling at 12 kHz. This experiment is based on 1H-13C J-coupling and yields a 1H-13C two-dimensional spectrum that shows signals from mobile protein regions that are not included in the fibril core.

RESULTS

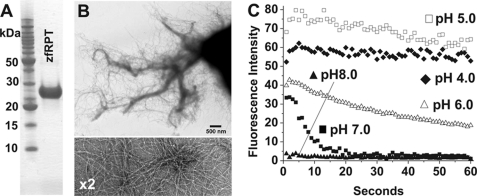

Human Splice Variant RPT Domain Forms Amyloid Specifically at Mildly Acidic pH

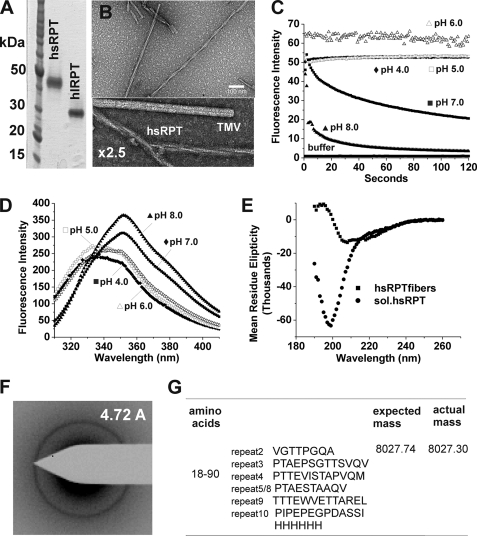

We first examined amyloid formation in vitro of a small splice variant, hsRPT, which contains a 42-amino acid truncation between repeats 5 and 8 (in bold in Fig. 1) (26), using a similar protocol as described previously (22). Paradoxically, purified hsRPT showed a slower migration on SDS-PAGE than hlRPT (Fig. 2A). At pH 5.0 with gentle agitation, we observed small filaments after 1 day of incubation, which became long unbranched straight fibers after several days. High magnification electron micrographs revealed these fibers to have a twisted ribbon morphology, suggesting they may be composed of two or more filaments, with an average fiber diameter of 18 nm (Fig. 2B and supplemental Fig. 2). No fiber formation could be observed at pH ≥7.0 when monitored using thioflavin T, as has been found for the human unspliced RPT (22). Moreover, amyloid formed at pH 5.0 quickly dissolved (within minutes) when exposed to neutral pH, yet remained stable under acidic conditions (Fig. 2C). Probing the C terminus of hsRPT by fluorescence using the sole tryptophan residue showed that at pH 5.0 hsRPT was blue-shifted by 20 nm, indicative of the tryptophan being shielded from the aqueous buffer (Fig. 2D). At a more neutral pH, a red shift was observed, indicating the residue is solvent-exposed. Circular dichroism studies showed that fibers exposed to pH 8.0 after overnight dialysis adopted a random coil conformation, whereas fibers at pH 5.0 had predominantly β-sheet, with some possible α-helical content (Fig. 2E). Electron diffraction with unoriented fibers (Fig. 2F) showed a ring corresponding to 4.72 ± 0.02 Å indicating a β-sheet pattern. As described below, one- and two-dimensional NMR data show that most residues examined have chemical shifts also indicative of β-sheet structure. Limited proteinase K digestion experiments revealed a proteinase K-resistant fragment corresponding to residues 18–90 as observed by LC-MS (Fig. 2G). Taken together, these data reveal that under acidic conditions reminiscent of the human melanosomal pH, hsRPT fibers adopt a β-sheet-rich conformation that has all the hallmarks of an amyloid. Upon exposure to neutral pH, these fibers dissolve and adopt a random coil conformation, a possible mechanism used for the regulation of hsRPT amyloid formation in vivo. Furthermore, the anomalous migration of hsRPT observed by SDS-PAGE may explain why no smaller fragments of the short Pmel17 isoform have been identified in vivo.

FIGURE 2.

RPT domain of the human splice variant (hsRPT) (26) forms fibers under nondenaturing conditions. A, SDS-PAGE (12%) analysis of His-tagged human hsRPT and unspliced human RPT purified under denaturing conditions. B, electron micrograph of hsRPT fibers formed at pH 5.0 with gentle agitation. High resolution electron micrograph image of hsRPT and tobacco mosaic virus for comparison is shown. C, hsRPT fibers monitored by thioflavin T over time at pH 4.0–8.0. D, intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence assay of hsRPT fibers formed at pH 5.0 and measured at pH 4.0–8.0. E, circular dichroism spectra of hsRPT fibers measured at pH 5.0 and 8.0. F, electron diffraction of fibers formed in vitro at pH 5.0 exhibits a reflection at 4.72 ± 0.02. G, limited proteinase K digestion of fibers reveals a proteinase K-resistant fragment corresponding to residues 18–90.

Mouse RPT Domain Forms Amyloid Specifically at Mildly Acidic pH

We next tested amyloid formation of the RPT domain of mouse Pmel17 (accession number NP_001096686), which shares only 50% sequence identity to human unspliced RPT (Fig. 1). At pH 5.0, mRPT formed small filaments after 1 day with gentle agitation, which became long twisted fibers after several days. High resolution electron micrograph images show mRPT fibers to have apparent width modulation indicating a twisted structure, possibly composed of paired filaments wrapped around one another (Fig. 3B and supplemental Fig. 3). These paired filaments had an average diameter of 14 nm. Under more neutral conditions (pH >6.0), no aggregation could be observed as monitored by thioflavin T and electron microscopy, even with prolonged incubation times. Hence, mRPT remained monomeric and could only form filaments under acidic conditions (∼pH 5.0).

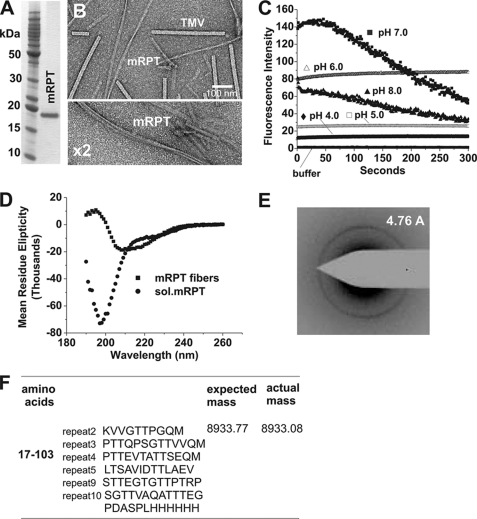

FIGURE 3.

RPT domain of mouse Pmel17 forms fibers under nondenaturing conditions at pH 5.0. A, SDS-PAGE (12%) analysis of His-tagged mRPT purified under denaturing conditions. B, electron micrograph of mRPT fibers formed at pH 5.0 with agitation. High resolution image of mRPT and tobacco mosaic virus is shown. C, mRPT fibers formed at pH 5.0 and monitored by thioflavin T over time at pH 4.0–8.0. D, circular dichroism spectra of mRPT fibers at pH 5.0 and 8.0. E, electron diffraction of fibers formed in vitro at pH 5.0 exhibits a reflection at 4.76 ± 0.02. F, proteinase K digestion of fibers reveal a proteinase K -resistant fragment corresponding to residues 17–103.

On binding to mRPT fibers at pH 4.0 and 5.0, thioflavin T displayed a moderate increase of fluorescence compared with pH 6.0 and above. A time course of mRPT fibers incubated at pH 4.0–8.0 and monitored by ThT showed that at pH 4.0–6.0 the mRPT fibers remain stable with little if any loss in fluorescence. At pH 7.0 and above, a gradual loss in fluorescence is observed (Fig. 3C). Comparison of mRPT and hsRPT fibers shows mRPT to be slightly more stable under neutral conditions (Fig. 2C versus 3C). Circular dichroism studies showed that mRPT fibers produced a random coil conformation after overnight dialysis at pH 8.0, compared with β-sheet and α-helical content at pH 5.0 (Fig. 3D). Electron diffraction data of these fibers supported a β-sheet pattern (Fig. 3E), with a major band corresponding to 4.76 Å. Limited proteinase K digestion showed residues 17–103 form a proteinase K-resistant fragment (Fig. 3F).

Zebrafish RPT Domain Forms Amyloid Specifically at Mildly Acidic pH

We finally examined amyloid formation of the low complexity repeat region of Pmel17 from zebrafish (accession number AAT37511.1), which shares no sequence similarity with human and mouse RPT. Initial attempts using various purified zebrafish Pmel17 fragments spanning this repeat sequence failed to form amyloid under conditions outlined previously (supplemental Table 1). However, we did find filament formation using the zebrafish Pmel17 fragment shown in Fig. 1. At pH 5.0 with gentle agitation, fibril formation was observed after several days. These fibrils were shown by electron microscopy to be straight, unbranched, and bundled, with significantly different appearance from those of mouse or human RPT fibrils. High magnification electron microscopy images show these filaments to be less than 4 nm in diameter (Fig. 4B and supplemental Fig. 4). Under less acidic conditions, no aggregation could be observed. Stability of these fibrils under various pH conditions show that at pH 4.0 and 5.0, zfRPT fibrils are stable over time with little loss in ThT fluorescence (Fig. 4C). At pH 7.0 and above, a rapid decrease in ThT fluorescence is observed indicating that these fibrils quickly dissociate. Electron microscopic examination likewise showed that fibrils remained at pH 4.0 and 5.0 but were nearly completely dissolved at pH 7.0 and above.

FIGURE 4.

RPT domain of zebrafish Pmel17 forms fibers under nondenaturing conditions. A, SDS-PAGE (12%) analysis of His-tagged zfRPT purified under denaturing conditions. B, electron micrograph images of zfRPT fibers formed at pH 5.0. C, zfRPT fibers formed at pH 5.0 and monitored by thioflavin T over time at pH 4.0–8.0.

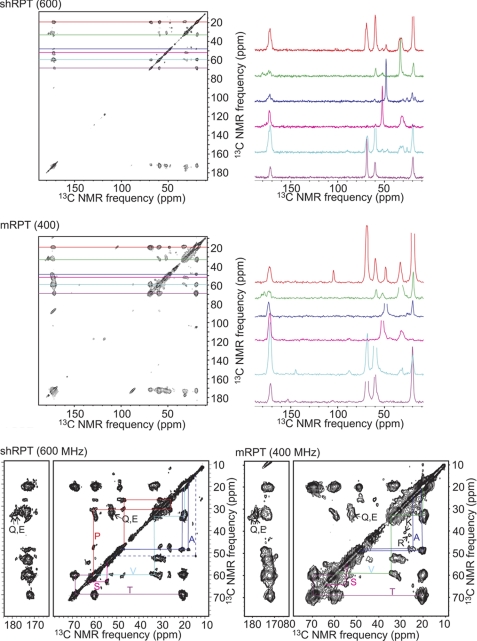

Solid-state NMR Structural Studies of hsRPT, mRPT, and zfRPT Fibrils

One-dimensional solid-state NMR spectra of hsRPT, mRPT, and zfRPT show chemical shifts of the carbonyl carbon labels at lower frequencies compared with the average random coil values, indicating that these residues are in β-sheet conformation (Table 1) (39). The sole exception is a minor fraction of the sole isoleucine residue of mRPT.

TABLE 1.

Chemical shift data indicate β-sheet structure

| Sample | Label (no. of residues) | Chemical shift | Random coil | Fraction of peak area |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ppm | ppm | |||

| hsRPT wet | [1-13C]Met (1)a | 169.86 | 174.6 | 1.0 |

| mRPT wet | [1-13C]Ile (1) | 174.63 | 174.7 | 0.19 |

| 173.37 | 174.7 | 0.81 | ||

| [1-13C]Met (3)a | 172.44 | 174.6 | 0.70 | |

| 168.88 | 174.6 | 0.30 | ||

| zfRPT dry | [1-13C]Ile (5) | 172.84 | 174.7 | 1.0 |

| Wet | [1-13C]Ile (5) | 172.55 | 174.7 | 1.0 |

a The initiator methionine is removed in E. coli during synthesis as shown by mass spectral analysis.

The in-register parallel β-sheet architecture is often observed in human pathogenic amyloid filaments (40–45) and in infectious amyloids of yeast prions (27, 46–48). This structure may be demonstrated by labeling a single atom (carbonyl or methyl carbon) and showing by solid-state NMR that the nearest labeled neighbor is the same atom in another molecule at a distance of about 4.7 Å, the spacing between β-strands in a β-sheet (49). The PITHIRDS-CT method of producing homonuclear dipolar recoupling (31) allows measuring this distance (r) because the time scale for signal decay is proportional to 1/r3.

The hsRPT fibrils labeled at the single Met residue with [13C]carbonyl and examined by the PITHIRDS-CT dipolar recoupling method show the rapid initial signal decay indicative of a nearest neighbor distance of about 0.5 nm (Fig. 5A). Because there is only one Met per hsRPT molecule, the nearest neighbor must be in another molecule. This result suggests the in-register parallel architecture, but it is not conclusive because we have only established this distance for a single site.

Wet mouse RPT filaments labeled with [1-13C]Ile (one residue) or with [3-13C]Ala (eight residues) were examined using the PITHIRDS-CT method (Fig. 5B). In both cases, the signal decayed at a rate indicative of a distance of about 0.5 nm between the nearest neighbor Ala methyl groups or Ile carbonyl groups, indicative of an in-register parallel architecture. There is only a single Ile residue, so the nearest neighbor in this case must be in another mRPT molecule. The same experiment carried out with wet filaments labeled with [1-13C]Met showed that both peaks gave rapid initial decay, indicating that at least two of the three Met residues are in in-register parallel structure (Fig. 5C).

Zebrafish RPT filaments, carbonyl-labeled at the five Ile residues, showed a one-dimensional spectrum with a chemical shift to lower frequency indicating β-sheet structure (Table 1). Dry filaments gave a rapid signal decay in the PITHIRDS-CT experiment, and the decay was substantially slowed when filaments were made starting with a mixture of fully [1-13C]Ile-labeled and unlabeled molecules (Fig. 5D). These results show that the nearest neighbor was about 0.5 nm distant and that the nearest neighbor was generally in another molecule.

Two-dimensional Solid-state NMR Experiments

Because of strong overlapping in the spectra, a result of the highly repeated sequence and duplicated amino acid residues in the Pmel sequences, the resolved signals (as shown in Fig. 6) can only be identified by residue type (Thr, Ser, Val, Pro, and Ala) or as groups of residues with similar α/β carbon chemical shifts (Glu and Gln). These observed residues in solid-state NMR spectra reflect the solid phase of the protein sequence that constitutes the fibril core. The chemical shifts of the α/β carbons of Thr, Ser, Val, and Ala residues in the fibril core imply prevailing β-sheet structures in both mRPT and hsRPT fibrils. We also saw relatively strong cross-peaks from the side chain atoms of Lys-17 (a unique residue site) and Arg in the solid-state NMR spectrum of labeled mRPT fibrils. Interestingly, the backbone of Lys-17 in mRPT was identified in the INEPT NMR spectrum of mobile residues.

FIGURE 6.

Two-dimensional 13C-13C spectra of uniformly 15N, 13C-labeled hsRPT and mRPT.

Additional structural characterization was obtained from the INEPT spectrum of the labeled mRPT (supplemental Fig. 6), which detects mobile parts of the protein sequence. Almost all residues observed in the INEPT spectrum had random coil chemical shifts indicating highly flexible secondary structures were adopted by these residues that are not in the fibril core. Partial assignments of the mobile residues in mRPT can be obtained from the knowledge that residues followed by a proline have distinct 13Cα/1Hα chemical shifts. Thus we identified Ala-5, Lys-17, Arg-77, Gly-91, and Ser-95 (supplemental Fig. 6) to be outside the fibril core. The appearance of Lys-17 residues in both flexible and nonflexible regions may result from heterogeneous fibril morphologies and/or more complicated interactions between the fibril core and flexible sections.

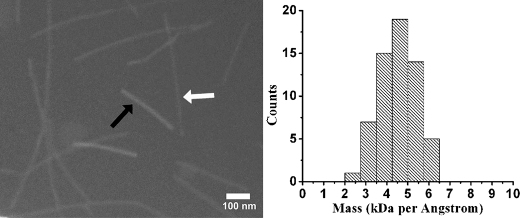

Mass Per Unit Length

Measurements of mass per unit length of unstained mouse RPT filaments were carried out using dark field electron microscopy as described previously (30). We found a mean mass/length of 2.12 ± 0.3 monomers/4.7 Å (Fig. 7). Given the twisted appearance and mass per length data, these fibrils seem to be twisted pairs of finer filaments, each with an in-register parallel β-sheet structure, similar to that of one form of Aβ amyloid filament (50).

FIGURE 7.

Mass per length measurements of mRPT fibrils. Dark field electron microscopy images are shown of mRPT fibers (white arrow) and tobacco mosaic virus (black arrow). Distribution of the mass per length values of mRPT fibrils reveals a mean mass/length of 2.12 ± 0.3 monomers/4.7 Å.

DISCUSSION

It may have been expected that because the RPT domain of Pmel17 is the most variable part of the protein, that amyloid formation, a feature shared by many Pmel17s across many species, would be determined by another more conserved part of the protein. Indeed, Watt et al. (24) suggested that the variation in the number and sequence of repeats in RPT makes it an improbable candidate for the core of the evolutionarily conserved functional amyloid fibrils. In this light, our finding that the very divergent mouse and zebrafish RPT domains form amyloid, in the same pH-dependent way as we previously found for human Pmel17, indicates that the variation of RPT is not a disqualifier as the amyloid core. Similarly, prion formation by the yeast Ure2 and Sup35 proteins does not depend on the sequence of their prion domains, only the amino acid composition (51, 52). Watt et al. (24) have shown convincing evidence that PKD can form amyloid, and like RPT, PKD is detected in the filaments in melanosomes, indicating that PKD is also a component of the filaments. Taken together, one could imagine fragments of Pmel17 such as RPT and PKD cooperating in some way to form the filamentous material seen in melanosomes.

The pH sensitivity of amyloid formation and stability is easily understood mechanistically in light of the many acidic residues in the RPT regions of each species. When a glutamate residue is protonated at acid pH, it could form hydrogen bonds in a manner similar to the β-zippers that are important in Huntington and yeast prion amyloids (53–55). The pH specificity also makes biological sense because Pmel17 is located in other cellular sites where filament formation does not (and should not) occur (10, 15, 56). Thus, our work may provide the mechanism of the physiological pH control of Pmel17 fiber assembly.

The paired helical filament appearance of mouse RPT amyloid, the mass per unit length of about two monomers per 4.7 Å, and the solid-state NMR data indicating an in-register parallel architecture are all consistent with a structure analogous to that of one type of Aβ fibrils (41). Protease digestion experiments indicated that the core of the filaments included most of the length of the mouse RPT domain except for the N-terminal 16 residues. The two-dimensional spectrum of uniformly 13C,15N-labeled mRPT fibrils shows Lys-17 side chain atoms in both flexible and nonflexible regions, suggesting the boundary of the N-terminal amyloid core is near this residue. Interestingly, the C terminus remains intact after proteinase K digestion, yet solid-state NMR experiments suggest that Arg-77, Gly-91, and Ser-95 are all outside the amyloid core. We interpret this as a result of interactions that occur between the fibril core and flexible sections of the protein.

The multihelical appearance of hsRPT is in contrast to the straight single filaments observed previously for hlRPT (22, 23), suggesting that the short splice variant forms a structure that is distinct from the full-length form. Further work will be needed to determine the detailed structure of the filaments of the RPT domain peptides. Whether the structural constraints we obtain correspond to genuine Pmel filaments can only be confirmed by studies of filaments isolated from animals or tissue culture cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mickey Marks for hPmel plasmids, and Julio Valencia and Vincent Hearing for valuable advice and reading the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health NIDDK Intramural Program.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–6 and Table 1.

- PKD

- polycystic kidney disease-like domain

- RPT

- repeat domain

- mRPT

- mouse RPT

- zfRPT

- zebrafish RPT

- hsRPT

- human splice RPT

- hlRPT

- human long RPT.

REFERENCES

- 1. Chapman M. R., Robinson L. S., Pinkner J. S., Roth R., Heuser J., Hammar M., Normark S., Hultgren S. J. (2002) Science 295, 851–855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wösten H. A., de Vocht M. L. (2000) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1469, 79–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Saupe S. J. (2007) Prion 1, 110–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Raposo G., Marks M. S. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 786–797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yamaguchi Y., Hearing V. J. (2009) Biofactors 35, 193–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Theos A. C., Truschel S. T., Raposo G., Marks M. S. (2005) Pigment Cell Res. 18, 322–336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dunn L. C., Thigpen L. W. (1930) J. Hered. 21, 495–498 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kwon B. S., Chintamaneni C., Kozak C. A., Copeland N. G., Gilbert D. J., Jenkins N., Barton D., Francke U., Kobayashi Y., Kim K. K. (1991) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 9228–9232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Adema G. J., de Boer A. J., van 't Hullenaar R., Denijn M., Ruiter D. J., Vogel A. M., Figdor C. G. (1993) Am. J. Pathol. 143, 1579–1585 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Theos A. C., Truschel S. T., Tenza D., Hurbain I., Harper D. C., Berson J. F., Thomas P. C., Raposo G., Marks M. S. (2006) Dev. Cell 10, 343–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hoashi T., Muller J., Vieira W. D., Rouzaud F., Kikuchi K., Tamaki K., Hearing V. J. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 21198–21208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leonhardt R. M., Vigneron N., Rahner C., Van den Eynde B. J., Cresswell P. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 16166–16183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Raposo G., Tenza D., Murphy D. M., Berson J. F., Marks M. S. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 152, 809–824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Berson J. F., Theos A. C., Harper D. C., Tenza D., Raposo G., Marks M. S. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 161, 521–533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Valencia J. C., Rouzaud F., Julien S., Chen K. G., Passeron T., Yamaguchi Y., Abu-Asab M., Tsokos M., Costin G. E., Yamaguchi H., Jenkins L. M., Nagashima K., Appella E., Hearing V. J. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 11266–11280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Saeki H., Oikawa A. (1983) J. Cell. Physiol. 116, 93–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Devi C. C., Tripathi R. K., Ramaiah A. (1987) Eur. J. Biochem. 166, 705–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bhatnagar V., Anjaiah S., Puri N., Darshanam B. N., Ramaiah A. (1993) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 307, 183–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Puri N., Gardner J. M., Brilliant M. H. (2000) J. Invest. Dermatol. 115, 607–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brilliant M. H. (2001) Pigment Cell Res. 14, 86–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hearing V. J., Phillips P., Lutzner M. A. (1973) J. Ultrastruct. Res. 43, 88–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McGlinchey R. P., Shewmaker F., McPhie P., Monterroso B., Thurber K. R., Wickner R. B. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 13731–13736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pfefferkorn C. M., McGlinchey R. P., Lee J. C. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. in press [Google Scholar]

- 24. Watt B., van Niel G., Fowler D. M., Hurbain I., Luk K. C., Stayrook S. E., Lemmon M. A., Raposo G., Shorter J., Kelly J. W., Marks M. S. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 35543–35555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wickner R. B., Edskes H. K., Shewmaker F., Nakayashiki T. (2007) Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5, 611–618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nichols S. E., Harper D. C., Berson J. F., Marks M. S. (2003) J. Invest. Dermatol. 121, 821–830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shewmaker F., Wickner R. B., Tycko R. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 19754–19759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McPhie P. (2001) Anal. Biochem. 293, 109–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kryndushkin D. S., Shewmaker F., Wickner R. B. (2008) EMBO J. 27, 2725–2735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen B., Thurber K. R., Shewmaker F., Wickner R. B., Tycko R. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 14339–14344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tycko R. (2007) J. Chem. Phys. 126, 064506 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pines A., Gibby M. G., Waugh J. S. (1973) J. Chem. Phys. 59, 569–590 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bennett A. E., Rienstra C. M., Auger M., Lakshmi K. V., Griffin R. G. (1995) J. Chem. Phys. 103, 6951–6958 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Petkova A. T., Tycko R. (2002) J. Magn. Reson. 155, 293–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ishii Y. (2001) J. Chem. Phys. 114, 8473–8483 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Takegoshi K., Yano T., Takeda K., Terao T. (2001) Chem. Phys. Lett. 344, 631–637 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Morcombe C. R., Gaponenko V., Byrd R. A., Zilm K. W. (2004) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 7196–7197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Morris G. A., Freeman R. (1979) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 101, 760–762 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wishart D. S., Sykes B. D., Richards F. M. (1991) J. Mol. Biol. 222, 311–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Antzutkin O. N., Balbach J. J., Leapman R. D., Rizzo N. W., Reed J., Tycko R. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 13045–13050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Petkova A. T., Ishii Y., Balbach J. J., Antzutkin O. N., Leapman R. D., Delaglio F., Tycko R. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 16742–16747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Der-Sarkissian A., Jao C. C., Chen J., Langen R. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 37530–37535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tycko R. (2006) Q. Rev. Biophys. 39, 1–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Luca S., Yau W. M., Leapman R., Tycko R. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 13505–13522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Margittai M., Langen R. (2008) Q. Rev. Biophys. 41, 265–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Baxa U., Wickner R. B., Steven A. C., Anderson D. E., Marekov L. N., Yau W. M., Tycko R. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 13149–13162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wickner R. B., Dyda F., Tycko R. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 2403–2408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shewmaker F., Kryndushkin D., Chen B., Tycko R., Wickner R. B. (2009) Biochemistry 48, 5074–5082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Benzinger T. L., Gregory D. M., Burkoth T. S., Miller-Auer H., Lynn D. G., Botto R. E., Meredith S. C. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 13407–13412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Petkova A. T., Yau W. M., Tycko R. (2006) Biochemistry 45, 498–512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ross E. D., Baxa U., Wickner R. B. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 7206–7213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ross E. D., Edskes H. K., Terry M. J., Wickner R. B. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 12825–12830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Perutz M. F., Johnson T., Suzuki M., Finch J. T. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 5355–5358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chan J. C., Oyler N. A., Yau W. M., Tycko R. (2005) Biochemistry 44, 10669–10680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Nelson R., Sawaya M. R., Balbirnie M., Madsen A. Ø., Riekel C., Grothe R., Eisenberg D. (2005) Nature 435, 773–778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Valencia J. C., Hoashi T., Pawelek J. M., Solano F., Hearing V. J. (2006) Pigment Cell Res. 19, 250–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.