Abstract

Phospholipase Cδ3 (PLCδ3) is a key enzyme regulating phosphoinositide metabolism; however, its physiological function remains unknown. Because PLCδ3 is highly enriched in the cerebellum and cerebral cortex, we examined the role of PLCδ3 in neuronal migration and outgrowth. PLCδ3 knockdown (KD) inhibits neurite formation of cerebellar granule cells, and application of PLCδ3KD using in utero electroporation in the developing brain results in the retardation of the radial migration of neurons in the cerebral cortex. In addition, PLCδ3KD inhibits axon and dendrite outgrowth in primary cortical neurons. PLCδ3KD also suppresses neurite formation of Neuro2a neuroblastoma cells induced by serum withdrawal or treatment with retinoic acid. This inhibition is released by the reintroduction of wild-type PLCδ3. Interestingly, the H393A mutant lacking phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate hydrolyzing activity generates supernumerary protrusions, and a constitutively active mutant promotes extensive neurite outgrowth, indicating that PLC activity is important for normal neurite outgrowth. The introduction of dominant negative RhoA (RhoA-DN) or treatment with Y-27632, a Rho kinase-specific inhibitor, rescues the neurite extension in PLCδ3KD Neuro2a cells. Similar effects were also detected in primary cortical neurons. Furthermore, the RhoA expression level was significantly decreased by serum withdrawal or retinoic acid in control cells, although this decrease was not observed in PLCδ3KD cells. We also found that exogenous expression of PLCδ3 down-regulated RhoA protein, and constitutively active PLCδ3 promotes the RhoA down-regulation more significantly than PLCδ3 upon differentiation. These results indicate that PLCδ3 negatively regulates RhoA expression, inhibits RhoA/Rho kinase signaling, and thereby promotes neurite extension.

Keywords: Neurochemistry, Neurodifferentiation, Phospholipase C, Phospholipid Metabolism, Rho, Neurite Outgrowth

Introduction

Neurite outgrowth and patterning are essential for wiring the nervous system during the development of cerebral cortex or maturation of cerebellum. Several studies have demonstrated that the Rho family of small GTPases, Cdc42, Rac, and Rho, has an important role in neurite outgrowth and neuronal migration, which mainly occurs via the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton (1). Activation of Cdc42 or Rac has been shown to promote neurite outgrowth and to regulate the formation of the cerebral cortex as shown in conditional knock-out mice or by the acute depletion of these molecules by means of in utero electroporation (2, 3). Conversely, Rho activity prevents neurite initiation and induces neurite retraction. Therefore, the concurrent Cdc42 and Rac activation and Rho inactivation are required for normal neurite initiation and outgrowth, thus regulating the organization of the developing brain. The inactivation of Rho during neuritogenesis appears to be regulated by several mechanisms. Rho GTPase-activating proteins, which enhance the intrinsic rate of GTP hydrolysis of Rho, suppress Rho activity during neurite formation (4). Recent studies also showed that Rho activity is down-regulated by the targeted degradation of the Rho protein via the ubiquitin/proteasome pathway (5).

The turnover of phosphoinositides is also implicated in neurite formation and extension (6). Generation of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2)3 as well as phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate seems to regulate neurite retraction in a growth factor-dependent manner, and several Rho family proteins are involved in the phosphoinositide signaling network in response to stimuli (7). Phospholipase C (PLC) is a key enzyme in phosphoinositide metabolism by catalyzing the hydrolysis of PI(4,5)P2, which leads to the generation of 2 second messengers, namely diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3). DAG stimulates activation of protein kinase C, and IP3 releases Ca2+ from the intracellular stores. On the basis of their structure and regulatory mechanism, 13 PLC isozymes have been identified and grouped into six classes, β, γ, δ, ϵ, ζ, and η, based on their structure and regulatory mechanisms. Among these classes, PLCδ is evolutionarily conserved from yeasts to mammals, and therefore, it is expected to have important physiological functions (8). The PLCδ class consists of the three isozymes, namely PLCδ1, -δ3, and -δ4 (9). We previously reported that PLCδ1 is necessary for skin homeostasis (10–12) and that PLCδ4 plays an essential role in the acrosome reaction of sperm (13, 14). However, the physiological functions of PLCδ3 still remain to be determined.

Because PLCδ3 is abundantly expressed in neuronal tissues and neuronal cell lines, we examined the role of PLCδ3 in neuronal differentiation. Here, we first show that PLCδ3 is an essential regulator of neuritogenesis in Neuro2A neuroblastoma cells, cerebellar granule cells, cortical neurons, and the developing cerebral cortex. We also demonstrate that PLCδ3 suppresses the Rho signaling pathway during neuritogenesis via the down-regulation of RhoA level.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmid Constructs

mPLCδ3-pENTR/U6 was generated according to Brummelkamp et al. (15). In brief, PLCδ3-specific sense and antisense sequences, flanking a 6-base hairpin, were annealed and inserted into pENTR/U6 or pGSU6-GFP vector for PLCδ3 knockdown (KD) by following the manufacturer's protocol. The oligonucleotides used for PLCδ3 knockdown were as follows: PLCδ3-targeting oligonucleotide, 5′-gatgagcttcaaggagatc-3′ and 5′-gatctccttgaagctcatc-3′ for granule cells and 5′-acagtaagatgagcttcaa-3′ and 5′-ttgaagctcatcttactgt-3′ for Neuro2a; and scramble oligonucleotide, 5′-gaattctccgaacgtgtca-3′ and 5′-tgacacgttcggagaattc-3′ for granule cells, and 5′-ctagtaagactagaagtgt-3′ and 5′-acacttctagtcttactag-3′ for Neuro2a. PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis was performed to generate GFP-PLCδ3 mutants. For the constitutively active (CA) mutant, Ala482–Gln519 was deleted and inserted with the Glu-Ser-Glu-Ser linker (16). As for CA-R79D, Arg79 in CA mutant was replaced with Asp by site-directed mutagenesis. The GST-tagged PLCδ3 H393A mutant, a catalytic mutant of GST-PLCδ3, was constructed by site-directed mutagenesis by using the following primers with the NaeI site: 5′-gggaacctgtcatctacgccggccacacgctcacct-3′ and 5′-aggtgagcgtgtggccggcgtagatgacaggttccc-3′. Wild-type PLCδ3 and all the PLCδ3 mutants were subcloned into pEGFP-C for expression, and the GST-H393A construct was prepared by using the GST-FastBac vector for the Baculovirus/Sf-9 expression system (17).

Culture, Knockdown, and Extensional Induction of Neuro2a Cells, Cerebellar Granule Cells, and Primary Cortical Neurons

Neuro2a cells were seeded at 1.5 × 104 cells in 35-mm dishes in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 1 mm sodium pyruvate and 10% fetal bovine serum 18–24 h before the transfection. Knockdown of PLCδ3 in Neuro2a was conducted by using the pENTR/U6 vector carrying the targeting sequence specific for mouse PLCδ3 and the scramble sequence as a control. For transient expression, DNA was introduced with FuGENE 6 by following the manufacturer's protocol (Roche Applied Science). The medium was changed to DMEM without serum after 24 h of transfection, and the cells were cultured for 48 h to induce neurite formation. Neuro2a cells were treated with 100 ng/ml phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate for 48 h or 0.5 μm ionomycin (Invitrogen) or 0.25 μm thapsigargin (Sigma) for 24 h.

Culture of cerebellar granule cells was essentially carried out as described previously (18). Cerebella were collected from P2-3 ICR mice, and granule cells were plated onto a 27-mm glass dish precoated with 100 μg/ml poly-l-lysine and 20 μg/ml laminin by adjusting the cell numbers to 1 × 106 cells/well. Transfection was performed with 100 μl of OptiMEM containing 1.25 μl of Lipofectamine LTX and 0.5 μg of pGSU-U6 vector carrying scrambled or PLCδ3 targeting sequence with EGFP flanked by internal ribosome entry site sequence as an indicator. The differentiation was induced by changing the medium by lowering the serum concentration from 10 to 5% with 4 μm cytosine arabinoside.

Cortical neurons were isolated from E14 embryos and cultured for 3 or 7 days in nerve-cell culture medium (Sumitomo Bakelite Co., Ltd.) with 4 μm cytosine arabinoside. Transfection was carried out with pCAGGS-EGFP and pGSU encoding scrambled or PLCδ3 targeting sequence by using AMAXA Nucleofector system (NucleofectorTM II). Preparation of astrocytes was followed as described previously (19).

Western Blots

Cells were cultured as described above, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then lysed with lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 120 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, and 1% Triton X-100). After sonication, the lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 14,800 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatants were subjected to SDS-PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidine difluoride (PVDF) membrane, and probed with appropriate antibodies for 1 h at room temperature as follows: anti-PLCδ3, anti-Rac (Sigma), and anti-β-actin (Sigma) antibodies. Anti-RhoA and anti-Cdc42 antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Blots were incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h (Dako Cytomation), and detection was performed using the electrochemiluminescence (ECL) system (Amersham Biosciences).

Real Time Reverse Transcriptase-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from control and PLCδ3KD Neuro2a cells cultured with or without serum by using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen), and reverse transcription was performed with SuperScript III (Invitrogen). The quantitative RT-PCR assay was carried out with the sequence-specific primers on the ABI PRISM 7000 (Applied Biosystems) with the QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR kit (Applied Biosystems) for real time monitoring of amplification. The expression of β-actin mRNA was used to normalize the expression of RhoA, Rac1, and Cdc42 mRNA. Primers for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were used for the determination of the PLCδ expression. The primers used were as follows: Rho, 5′-ctggtgattgttggtgatgg-3′ (forward) and 5′-gcggtcataatcttcctgtc-3′ (reverse); Cdc42, 5′-gcgcgggatctgaaggctgtca-3′ (forward) and 5′-tgcttttagtatgacgacaacacca-3′ (reverse); Rac, 5′-ccagtgaatctgggcctatggg-3′ (forward) 5′-tggccagcccctgcgggtag-3′ (reverse); β-actin, 5′-accaactgggacgacatggagaaga-3′ (forward) and 5′-acgaccagaggcatacagggacag-3′ (reverse); GAPDH, 5′-ccatgccatcactgccaccc-3′ (forward) and 5′-tgtcatcatacttggcaggtttc-3′ (reverse); PLCδ1, 5′-cgcagccaagtgcaacacaag-3′ (forward) and 5′- ggaagccatctcatagaatgcc-3′ (reverse); PLCδ3, 5′-gcgcagcttctaagcacatattc-3′ (forward) and 5′-cttgaaggcgatggtgaggc-3′ (reverse); and PLCδ4, 5′-aggtgatcagtggccaacaac-3′ (forward) and 5′-ttgttctccacatggctggtc-3′ (reverse).

Cellular Imaging by Immunofluorescence

PLCδ3KD cells transfected with mutant GFP-PLCδ3 or the Myc-tagged mutant Rho family GTPase were cultured on cover glass in 35-mm dishes. Samples were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS for 30 min and incubated with rhodamine/phalloidin for 1 h at room temperature. The samples were mounted with the Slow-fade gold antifade kit (Molecular Probes), and the morphology of the cells was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy (Keyence BZ-8000). The percentage of neurite outgrowth was calculated by counting the GFP-positive or Rho family GTPase-transfected cells bearing neurites that were longer than two cell body lengths after a 48-h serum withdrawal. The localization of GFP, GFP-PLCδ1, GFP-PLCδ3, and GFP-PLCδ3 mutants was analyzed by using Olympus FV1000 confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus). For cortical neurons or granule cells, samples were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 min and permeabilized with PBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100. After blocking with PBS containing 1% BSA and 1% goat serum, cells were incubated with anti-MAP2, anti-Tau1 (Millipore), or anti-Tuj1 (Sigma) antibody for 2 h at room temperature or overnight at 4 °C. Alexa Fluor secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) were used for the detection of immunofluorescence and analyzed by Olympus FV1000 confocal laser scanning microscope.

Baculovirus Expression and Purification

Recombinant GST-PLCδ3, GST-H393A, GST-CA, and GST-CA-R79D were prepared by the baculovirus/Sf9 expression system. Infected Sf9 cells were lysed with lysis buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.12 m NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, and 1% Triton X-100) containing protease inhibitor mixtures (Roche Applied Science). The cell lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 min after sonication, and the supernatants were incubated with glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads at 4 °C overnight. Recombinant PLCδ3 was purified with elution buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 50 mm glutathione) and dialyzed three times in ice-cold PBS.

Measurement of PLC Activity

The PLC activity was assayed by hydrolysis of PI(4,5)P2 in a 50-μl reaction mixture containing 20,000 dpm of [3H]PI(4,5)P2 (PerkinElmer Life Sciences), 40 μm PI(4,5)P2, and 50 μm phosphatidylethanolamine as phospholipids micelles. The micelles were incubated with recombinant PLC at 37 °C for 5 min, and the reaction was stopped by adding 1 ml of chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v). Radioactive IP3 was extracted with 0.25 ml of 1 n HCl, and radioactivity in the upper aqueous phase was measured for 1 min in a liquid scintillation counter (17).

Knockdown by in Utero Electroporation

Pregnant ICR mice carrying E14 embryos were anesthetized, and a right ventral incision was made to access the uterus. 1 μl of plasmid DNA (5 μg/ml) with 0.1% Fast Green containing 4 μg of pGSU vector for siRNA and 1 μg of CAGGS-EGFP vector for visualization, respectively, was injected into the lateral ventricles of embryonic brains from outside the uteri with a glass micropipette. For confirmation of PLCδ3 knockdown in developing cortex in vivo, 1 μg of FLAG-PLCδ3 vector, with 3 μg of pGSU-U6 knockdown vector and 1 μg of CAGGS-EGFP vector, was introduced into the lateral ventricles of E14 embryonic brain as the same way described above. By holding the embryo in utero with forceps-type electrodes, 50 ms of 33-V electric pulses were delivered four times at intervals of 950 ms. After the electroporation, uteri were placed back in the abdominal cavity, allowing the embryos to continue their development. At the postnatal day 0 or 2 (P0 or P2) stage, electroporated brains were sectioned by cryostat to obtain the dorso-lateral region of the cerebral cortices.

Immunohistochemistry

Frozen sections of fixed embryonic brains with 4% paraformaldehyde were treated with blocking buffer supplied with TSA biotin system (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) for 30–60 min and subsequently incubated with anti-MAP2 or anti-GFP antibody for 1 h at room temperature. After three times washes in PBS, sections were treated with Alexa 488- or 568-conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes) for 1 h at room temperature. Sections were also stained with 2 μg/ml Hoechst 33258 for 5 min, and the fluorescent images were obtained by Olympus FV1000 confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus).

RESULTS

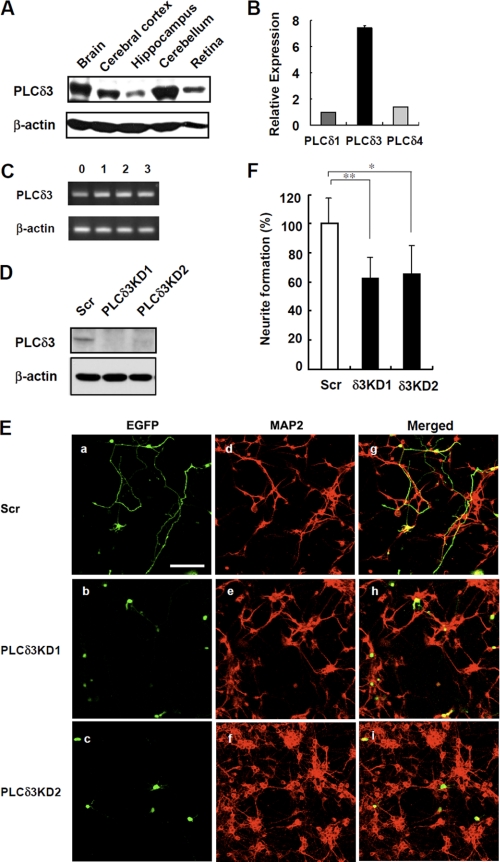

PLCδ3 Regulates Neurite Outgrowth in Cerebellar Granule Cells

Several studies have shown that PI3K and several PLC isoforms are involved in neurite outgrowth by using neuroblastoma cell lines and cortical neurons (6, 20). Therefore, we tried to examine the physiological function of PLCδ3 in neuronal cells. PLCδ3 is enriched in the mouse adult brain and is especially abundant in the cerebellum and cerebral cortex (Fig. 1A). To characterize the physiological importance of PLCδ3 in neurite extension, we first examined the effects of PLCδ3 knockdown on neurite in cerebellar granule cells isolated from the cerebellum. In isolated granule neurons, the expression of PLCδ3 was relatively high among PLC δ-type isozymes (Fig. 1B). Cultured granule cells show progressive exogenesis during the first several days preceding the development of shorter dendrites (18), and PLCδ3 is expressed throughout the 3 days of culture in vitro (Fig. 1C). We used two distinct targeting sequences for PLCδ3KD and confirmed the PLCδ3 targeting sequence for each shRNA was effective to suppress the expression of endogenous PLCδ3 in Neuro2a cells (Fig. 1D). Then transient PLCδ3KD was performed using the pGSU6-GFP vector carrying the scrambled or PLCδ3 targeting sequences in granule cells. GFP expression is regulated by the internal ribosome entry site sequence in the pGSU6-GFP vector and was utilized as a marker for the transfected cells. An anti-MAP2 antibody was also used as a marker of granule cells (Fig. 1E). No residual glial fibrillary acidic protein-positive astrocyte remained in the culture in the presence of cytosine arabinoside (Fig. 1E and supplemental Fig. 1). Interestingly, the neurites of GFP-positive PLCδ3KD cells were less elongated than those of control GFP-positive cells (Fig. 1E). The number of granule neurons with neurites longer than two cell body lengths was counted, and the ratio of neurite formation in PLCδ3KD cells knocked down by PLCδ3KD1 or PLCδ3KD2 shRNA was ∼60 or 65% that observed in control cells, respectively (Fig. 1F). These results strongly suggest that PLCδ3 is involved in neuronal extension in cerebellar granule cells.

FIGURE 1.

PLCδ3 regulates neuronal outgrowth in cerebellar granule cells. A, expression of PLCδ3 was analyzed in the whole brain, cerebral cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum, and retina by Western blots with a monoclonal anti-PLCδ3 antibody that specifically recognizes the X-Y region of PLCδ3. β-Actin is used as the loading control. B, expression levels of PLCδ isozymes in isolated cerebellar granule cells were determined by qRT-PCR. The relative amounts are represented as the ratio to that of PLCδ1 mRNA. C, PLCδ3 was expressed throughout the 3-day culture of cerebellar granule cells isolated from P2–3 ICR mice. The amounts of PLCδ3 were examined by RT-PCR. D, endogenous PLCδ3 was effectively down-regulated by transfection with pGSU6-GFP vector carrying scrambled sequence or two distinct shRNA targeting mouse PLCδ3 sequence in Neuro2a cells. The expression levels of PLCδ3 were determined by Western blots. E, PLCδ3 knockdown caused significant inhibition of neurite outgrowth of cerebellar granule cells. 18 h after plating, cultured granule cells were transfected with control pGSU6-GFP (Scr, panels a, d, and g) or PLCδ3 shRNA expressing pGSU6-GFP (PLCδ3KD1, panels b, e, and h, or PLCδ3KD2, panels c, f, and i) and cultured for another 48 h. Note that PLCδ3 knockdown caused lower population of the granule cells with neurite compared with GFP-positive control cells (panels a–c). Middle (panels d–f) shows the granule cells stained with anti-MAP2 antibody, and right (panels g–i) shows the merged image. Scale bar, 100 μm. F, percentage of neurite formation in both GFP and MAP2-positive cells was evaluated and represented as a relative value. The rate of neurite outgrowth was determined by the population of neurons showing more than two cell body lengths. The data indicate the mean ± S.D. of five experiments obtained from average number of 600 GFP-positive cells counted for each transfection by microscopy. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 (Tukey's multiple comparison test).

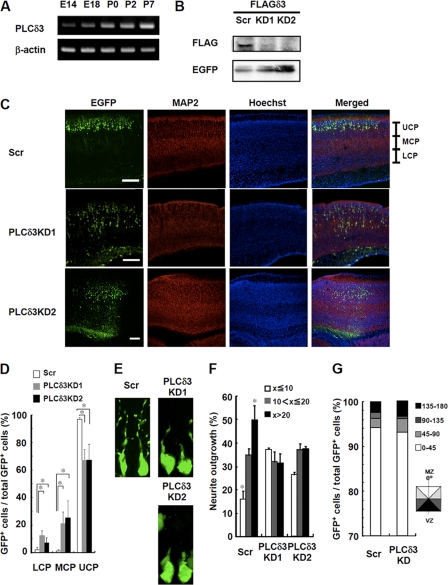

PLCδ3 Knockdown in the Embryonic Cerebral Cortex Causes the Retardation of Neuronal Migration

We next examined the importance of PLCδ3 on the development of the cerebral cortex in vivo. PLCδ3 levels were gradually increased throughout the development of the cerebral cortex (Fig. 2A). We then examined the involvement of PLCδ3 in neuronal migration in cortical plates using in utero electroporation method. We confirmed that two kinds of PLCδ3 sequences worked for the knockdown in vivo by the co-transfection with FLAG-tagged PLCδ3 in the cortex by in utero electroporation (Fig. 2B). We then introduced the pGSU-shRNAi vector containing each of the two different sequences into the lateral ventricles of embryonic mice brains at E14, and we observed migrating neurons in the cerebral cortex. When we used control vector, GFP-positive neurons reached the upper cortical plate (UCP) at postnatal day 2 stage (Fig. 2C). Conversely, the migrating neurons in PLCδ3KD brain of both sequences were abnormally retarded in the lower or middle cortical plate (Fig. 2C). We calculated the ratio of migrating neurons in each region (Fig. 2D). In the control cerebral cortex, the majority of the migrating neurons were present in the UCP, whereas the ratio of migrating neurons in the UCP was only ∼60%, and the ratio in the middle or lower cortical plate was increased in the PLCδ3KD brain. Furthermore, we analyzed the morphology of GFP-positive migrating neurons. Fig. 2E shows the images of the representative neurons with an average length of leading edges in each case. PLCδ3 knockdown caused an inhibition of leading process in cortical plate (Fig. 2E). Migrating neurons were categorized into three groups based on their length at P0 as follows: less than or equal to 10 μm, 10–20 μm, and more than 20 μm. 50% of the control cells was more than 20 μm in length, and only 15% of those were less than or equal to 10 μm, whereas only about 35% of the PLCδ3KD cells were more than 20 μm in length, and nearly 30% of those exhibited a length shorter than 10 μm (Fig. 2F). On the other hand, more than 90% of the migrating PLCδ3KD neurons were tangentially oriented toward the marginal zone from the ventricular zone as well as control GFP-positive neurons, suggesting that PLCδ3 does not regulate the orientation of cortical migration (Fig. 2G). These results suggest that PLCδ3 is required for extension of leading edge and regulation of the cortical neuronal migration in the developing cerebral cortex.

FIGURE 2.

PLCδ3 knockdown in embryonic cerebral cortex causes the retardation of neuronal migration. A, expression of PLCδ3 during embryonic or postnatal brain development. RNA was isolated from cerebral cortex at E14, 18, P0, P2, or P7 stage, and the amounts of PLCδ3 were determined by RT-PCR. B, PLCδ3 knockdown in vivo was successfully conducted with two distinct targeting sequences. The pCAGGS-EGFP and pGSU6 vector carrying scrambled (Scr) or PLCδ3 targeting sequence was co-introduced with FLAG-PLCδ3 sensitive to shRNAs into the lateral ventricles by in utero electroporation at E14 stage. The transfection efficiency and the expression level of exogenous FLAG-PLCδ3 at P2 stage in cortex were determined by immunoprecipitation with anti-EGFP and anti-FLAG antibodies, and each immunoprecipitant was subjected to Western blotting with anti-FLAG and anti-EGFP antibodies, respectively. C, PLCδ3 knockdown by in utero electroporation method inhibits neuronal migration in cerebral cortical plates. Transient PLCδ3 knockdown was performed at E14 stage with CAGGS-EGFP vector, and the migration of EGFP-positive cortical neurons was analyzed at P2 stage. Note that PLCδ3KD neurons show significant retardation of the cortical migration to marginal zone. The region of cortical plate was divided into lower (LCP), middle (MCP), and upper (UCP) region. Scale bar, 200 μm. D, numbers of migrating neurons in each region were counted, and the extent of neuronal migration was represented as the percentage of GFP-positive neurons. The values were obtained from average numbers of 1000 GFP-positive cells from the sections. Steel's multiple comparison test (analysis of variance with post hoc test) showed significant difference between control and each PLCδ3 knockdown treatment (*, p < 0.05). E, representative morphology of GFP-positive control or PLCδ3KD neurons was shown. Note that PLCδ3 knockdown caused the inhibition of neurite outgrowth. F, percentage of neurite outgrowth was indicated by categorizing the migrating cortical neurons showing less than or equal to 10 μm, 10–20 μm, or more than 20 μm. The populations were obtained from average number of 1800 GFP-positive migrating neurons. Statistical analysis showed significant difference between the indicated population of GFP-positive control and PLCδ3KD cells (*, p < 0.05). G, orientation of GFP-positive migrating neurons at P0 stage were categorized into 4 columns based on the angle toward tangential orientation to the cortical plate. No significant difference in the orientation was detected between control and PLCδ3KD neurons tangentially migrating away from the ventricular zone (VZ) to marginal zone (MZ).

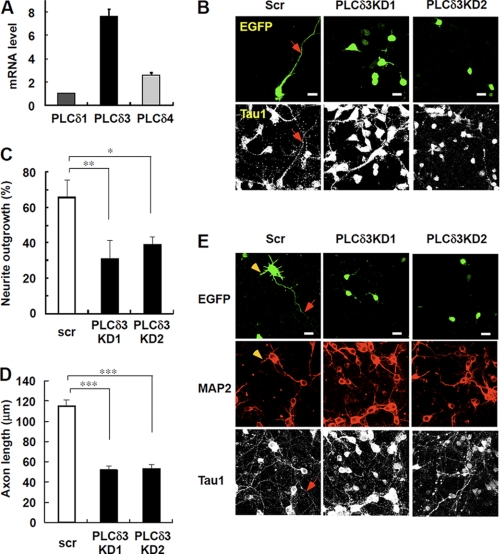

PLCδ3 Is Necessary for Outgrowth of Axon and Dendrites in Cortical Neurons

To gain more insight into the mechanism of neuronal function in developing cerebral cortex, we next analyze the effect of PLCδ3 knockdown on the exogenesis or dendritogenesis by preparing primary cortical neurons. PLCδ3 is highly expressed compared with other PLCδ isozymes in cerebral cortex as determined by quantitative real time RT-PCR analysis (Fig. 3A). We confirmed that neither astrocytes nor oligodendrocytes co-existed in the cortical culture in the presence of cytosine arabinoside at 3 days in vitro (3DIV) (supplemental Fig. 2). The expression levels of each PLCδ isozyme were not significantly changed throughout the cortical differentiation (data not shown), and knockdown of the endogenous PLCδ3 by two shRNA was performed by using the same PLCδ3-targeting shRNA vectors (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, PLCδ3 knockdown caused the significant inhibition of axonal outgrowth (31.4% for KD1 and 39.7% for KD2) at 3DIV, whereas control cells exhibited normal exogenesis at the same stage (65.9%, Fig. 3, B and C). PLCδ3 was also involved in the regulation of axonal outgrowth as shown in the significant decrease in the axon length in PLCδ3KD neurons at 3DIV (Fig. 3D). These results indicate that PLCδ3 is important for both neuritogenesis and exogenesis in cortical neurons. We also examined the effects of PLCδ3 knockdown on the maturation of axon or dendrite of cortical neurons at 7DIV. EGFP-positive control neurons showed the normal development of axon or dendrites as indicated by arrows or arrowheads in Fig. 3E, respectively. However, PLCδ3KD neurons showed immature axonal or dendrite formation at 7DIV (Fig. 3E), suggesting that PLCδ3 is also important for exogenesis or dendritogenesis after the establishment of polarity during neuronal development.

FIGURE 3.

PLCδ3 is involved in axon and dendrite outgrowth in cortical neurons. A, relative amounts of PLCδ isozymes in isolated cortical neurons from E14 mice were analyzed by real time qRT-PCR. The relative amounts are represented as the ratio to that of PLCδ1 mRNA. PLCδ3 is highly expressed in cortical neurons compared with PLCδ1 or PLCδ4. B, effects of PLCδ3 knockdown on neurite outgrowth in cortical neurons. pGSU6 vector carrying scrambled (Scr) or PLCδ3 targeting sequence was introduced into cortical neurons isolated from E14 mice by electroporation (AMAXA Nucleofector kit) and cultured on poly-l-lysine-coated glass bottom dishes for 3DIV. GFP signal filled in the tip of the outgrowing axon indicated as an arrow. Cortical neurons were stained with anti-Tau1 antibody. Scale bar, 20 μm. C, data represent rate of neurite outgrowth in control or PLCδ3 knocked down cortical neurons (3DIV) by two different shRNA sequences. Data represent the mean ± S.D. of three experiments (n = 220). Tukey's multiple comparison test was carried out between each population (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01). D, effects of PLCδ3 knockdown on axonal length in cortical neurons cultured for 3 days. Cortical neurons were stained with anti-MAP2 and anti-Tau1 antibodies. Data represent the mean ± S.E. of three experiments (n = 120). ***, p < 0.001 (Steel-Dwass multiple comparison test). E, effects of PLCδ3 knockdown on axonal or dendrite outgrowth in cortical neurons (7DIV). Although normal exogenesis (arrows) and dendritogenesis (arrowheads) were observed at 7DIV, GFP-positive PLCδ3KD neurons showed immature outgrowth of axon or dendrites. Scale bar, 20 μm.

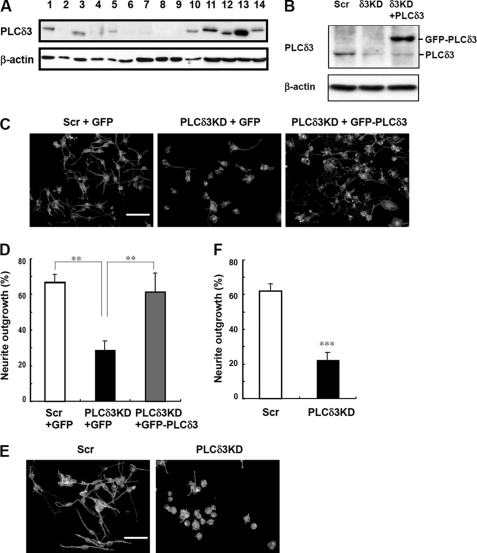

PLCδ3 Is Necessary for Neurite Extension in Neuro2a Cells

We next examined the expression of PLCδ3 in several cell lines, including neuronal cell lines (Fig. 4A). PLCδ3 was most abundant in the PC12 cell line among these cells. N1E115 and Neuro2a cells have relatively higher amounts of PLCδ3 than the other non-neuronal cell lines. Because Neuro2a cells showed higher transfection efficiency than the other neuronal cell lines, we used these cells for the following studies.

FIGURE 4.

PLCδ3 is abundant in neuronal cell lines and involved in neurite outgrowth in Neuro2a cells. A, PLCδ3 is enriched in neuronal cell lines. Expression profiling of PLCδ3 in cell lines is shown. The amount of PLCδ3 was analyzed by Western blots by using β-actin as a control in the following cells: lane 1, U2OS; lane 2, Saos2 cells; lane 3, MC3T3; lane 4, OP9; lane 5, HEK293; lane 6, Madin-Darby canine kidney cells; lane 7, mouse embryonic fibroblasts; lane 8, C6 glioma; lane 9, HL60S; lane 10, COS7; lane 11, N1E-115; lane 12, HeLa; lane 13, PC-12; and lane 14, Neuro2a. B, Neuro2a cells were transiently transfected with pENTRTM/U6 vectors carrying the control (Scr) or PLCδ3-targeting sequence (KD), and the PLCδ3 level was restored by the introduction of GFP-PLCδ3 into PLCδ3KD cells. The cells were incubated in DMEM without serum for 48 h to induce neurite outgrowth, and the amounts of PLCδ3 were analyzed using Western blotting. β-Actin was used for normalization. C, Neuro2a was transfected with control pENTRTM/U6 (Scr) or PLCδ3-targeting shRNA vector (PLCδ3KD), and PLCδ3 level was restored by the co-transfection of GFP-PLCδ3 into PLCδ3KD cells at the same time. Empty vector (pEGFP-C) is used as control for the introduction. The medium was changed 24 h after the transfection. Scale bar, 100 μm. D, data represents the mean ± S.D. of three experiments (C). Tukey's multiple comparison test was carried out between the indicated populations (**, p < 0.01). E, Neuro2a cells transfected with control pENTRTM/U6 (Scr) or PLCδ3-targeting shRNA vector (PLCδ3KD) were treated with 20 μm RA in the presence of 2% serum for 24 h. The cells were stained with rhodamine/phalloidin, and the rate of neurite extension was quantified. Scale bars, 100 μm. F, data represent the mean ± S.D. of three experiments (Fig. 3E). ***, p < 0.001 (Student's t test).

We performed a transient knockdown of PLCδ3 using the pENTR/U6 vector carrying the scrambled or target sequence against mouse PLCδ3 in Neuro2a cells (Fig. 4B). The transfection efficiency was ∼90% under these conditions in Neuro2a cells. Reintroduction of siRNA-resistant form of GFP-PLCδ3 was also carried out in PLCδ3KD cells, and we confirmed the substantial amounts of exogenous GFP-PLCδ3 in the KD cells (Fig. 4B). Neuronal extension was induced by serum withdrawal for 48 h (Fig. 4, C and D) or treatment with 20 μm retinoic acid (RA) (Fig. 4, E and F), and the extent of differentiation was quantified by counting the number of cells having neurites with lengths greater than 2-fold their somatic length 48 h after differentiation. Neurite extension was induced in the control cells by serum withdrawal (left panel in Fig. 4C). On the other hand, PLCδ3 knockdown caused a significant inhibition of neurite outgrowth (middle panel in Fig. 4C). In the control Neuro2a cells, 67% of the cells had neurite extension, whereas only 29% of PLCδ3KD cells exhibited neurite extension (Fig. 4D). The extension of neurites was restored by the reintroduction of GFP-PLCδ3 (right panel in Fig. 4C); neurite extension was observed in 62% of cells (recovery rate, 93%), indicating that PLCδ3 is necessary for serum-starved Neuro2a neurite extension. In the case of RA treatment, depletion of PLCδ3 also inhibited neurite extension (Fig. 4E). The rate of neurite extension was ∼35% that observed in the control cells (control, 62% and PLCδ3KD, 23%) (Fig. 4F).

PI(4,5)P2 Hydrolyzing Activity Is Necessary for Proper Neurite Extension upon Serum Withdrawal

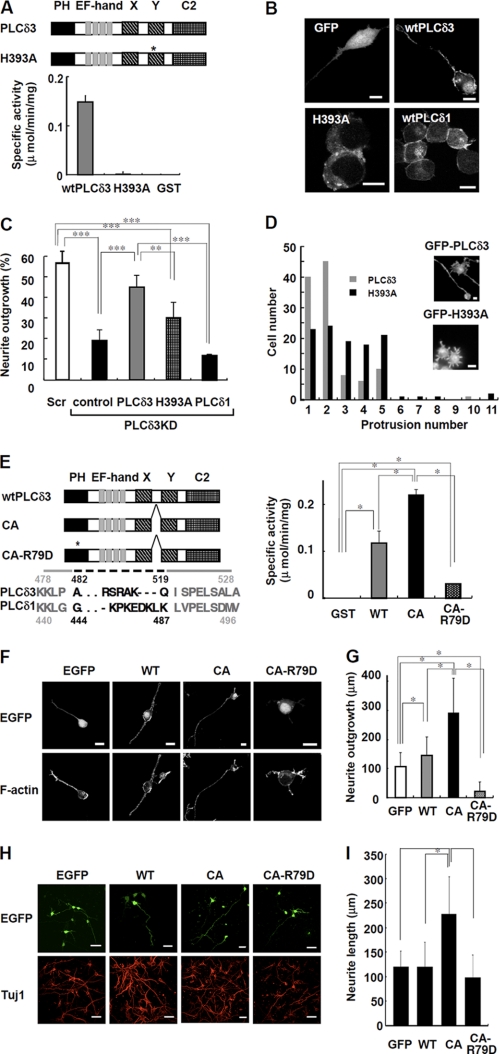

To examine whether the PI(4,5)P2 hydrolyzing activity of PLC is necessary for neurite extension, we generate a mutant of PLCδ3 that lacks PLC activity (Fig. 5A). The primary sequence of PLCδ3 is very similar to that of PLCδ1, and the His356 of PLCδ1 is one of the essential catalytic residues for the hydrolysis reaction. By analogy with PLCδ1, the His393 of PLCδ3 was predicted to catalyze PI(4,5)P2 hydrolysis in PLCδ3. To examine whether His393 is responsible for the PI(4,5)P2 hydrolyzing activity of PLCδ3, recombinant PLCδ3 was prepared using a baculovirus expression system, and PLC activity was measured (Fig. 5A). There was no hydrolyzing activity for the H393A mutant, indicating that the point mutation caused a complete loss of catalytic activity.

FIGURE 5.

PI(4,5)P2 hydrolyzing activity regulates the neurite numbers and neurite outgrowth upon serum withdrawal. A, PI(4,5)P2 hydrolyzing activity of GST-tagged wild-type PLCδ3 (wtPLCδ3), H393A, or GST. Domain structure of wild-type PLCδ3 and H393A is shown. The asterisk indicates the position of the point mutation in catalytic domain of H393A. Recombinant H393A lacks PLC activity. B, GFP-tagged PLCδ1, PLCδ3, or H393A mutant was transfected into Neuro2a cells for 24 h, and the cells were cultured in DMEM without serum for 48 h. GFP was used as a control. Scale bars, 10 μm. C, effect of catalytic activity on neurite outgrowth. Cells were subjected to PLCδ3 knockdown and subsequently transfected with GFP, GFP-PLCδ3, GFP-H393A, or GFP-PLCδ1. After transfection, the cells were incubated in DMEM without serum for 48 h, and the percentage of neurite outgrowth in GFP-positive cells was quantified and represented in a bar graph (%). Data represent the mean ± S.D. of three experiments. Tukey's test showed significant difference between indicated two groups (**, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001). D, cells transfected with mutant H393A show formation of supernumerary protrusions. GFP-PLCδ3 or GFP-H393A was introduced into PLCδ3KD cells, and the cells were stained with rhodamine/phalloidin after a 48-h incubation in DMEM without serum. A histogram displaying the number of cells plotted against the indicated number of neurites/protrusions is shown. The population of GFP-PLCδ3 or GFP-H393A transfected cells showing each neurite/protrusion numbers was analyzed 48 h after serum withdrawal (gray bars, wild-type PLCδ3; black bars, H393A) irrespective of their length. Scale bar, 10 μm. E, PI(4,5)P2 hydrolyzing activity in recombinant GST-tagged PLCδ3, CA, or CA-R79D. Domain structure of wtPLCδ3, CA mutant or its PH domain mutant (CA-R79D) is shown. The asterisk indicates the position of the point mutation of Arg79 in PH domain required for the specific PI(4,5)P2 binding. Dashed line indicates the deleted amino acid residues located between catalytic X and Y region in CA mutant. CA mutant shows higher PLC activity than wtPLCδ3, whereas CA-R79D shows a little activity. Tukey's test showed significant difference between indicated two groups (*, p < 0.05). F, Neuro2a cell expressing CA promotes neurite extension. GFP-tagged wtPLCδ3, CA, or CA-R79D was transfected into Neuro2a cells for 24 h, and the neurite extension was analyzed upon serum withdrawal. CA mutant promoted neurite extension. The point mutation in PH domain abolished the targeting of CA mutant to plasma membrane. Scale bars, 20 μm. G, effect of wtPLCδ3, CA, or CA-R79D on neurite growth was analyzed by quantification of the longest neurite extending from each transfected cell in the absence of serum. The average length was represented as bar graphs (n = 100), and it is notable that CA mutant but not CA-R79D promotes significant neurite outgrowth. The Steel-Dwass multiple comparison test showed significant differences between two conditions (*, p < 0.05). H, constitutively active PLCδ3 effectively promote the neurite outgrowth in cortical neurons. The effect of wtPLCδ3, CA, or CA-R79D tagged with EGFP on neurite growth was analyzed by quantification of the longest neurite from each EGFP-positive cortical neuron (DIV3). The neurons were stained with Tuj1 as a neuronal marker. Scale bars, 40 μm. I, data represent the average neurite length of each transfected neuron (n = 100). The Steel-Dwass test showed significant differences between two conditions (*, p < 0.05).

We also examined the localization of GFP-tagged PLCδ1, PLCδ3, and H393A in Neuro2a cells in the absence of serum. PLCδ1 was mainly localized at the plasma membrane, and lower amounts of PLCδ1 were detected in the cytoplasm and nucleus as shown previously (21). Wild-type GFP-PLCδ3 was localized at the plasma membrane and nucleus (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, the H393A mutant was not localized in the plasma membrane or nucleus, suggesting that this mutation affects not only its PLC activity but also its localization signal.

When we introduced the H393A mutant into PLCδ3KD Neuro2a cells, neurite outgrowth was not restored, and the appearance of the neurite extensions was completely different (Fig. 5, C and D). The introduction of the catalytic mutant H393A induced the formation of multiple short protrusions in contrast to the normal neurite outgrowth induced by wild-type PLCδ3 (Fig. 5D). Therefore, we examined the distribution of cells and neurite or protrusion numbers in these cells by simply counting them irrespective of their length. A significant number of H393A-transfected cells generated 3–5 protrusions, although wild-type PLCδ3-transfected cells had 1 or 2 primary neurites (Fig. 5D). This result clearly indicates that the generation of supernumerary protrusions is facilitated in PLCδ3KD cells expressing the H393A mutant. These results show that PLC activity is critical for the commitment of neurite generation and extension during the differentiation process. Noticeably, PLCδ1 could not rescue the inhibitory effect of PLCδ3 knockdown on neurite outgrowth (Fig. 5C), suggesting an isoform-specific signaling pathway for neurite elongation.

Constitutively Active PLCδ3 Stimulates Neurite Elongation in Both Neuro2a and Cortical Neurons

Recently, Hicks et al. (16) reported that the deletion of X/Y linker region results in the constitutive activation of PLCβ2 and PLCδ1. To further examine the effects of PLCδ3 activity on neurite outgrowth, we deleted the X-Y linker region of PLCδ3 by following the case for PLCδ1 (Fig. 5E) and characterized the enzymatic property of the PLCδ3 mutant (CA). Arg79 in pleckstrin homology (PH) domain, which is putatively important for specific PI(4,5)P2 binding, was also mutated in the CA mutant (CA-R79D). The specific activity of CA or wild-type PLCδ3 was 0.22 or 0.12 μmol/min/mg, respectively. In contrast, CA-R79D had significantly lower PLC activity (0.03 μmol/min/mg).

To examine the physiological role of the PLCδ3 activity, we introduced GFP-PLCδ3, CA, or CA-R79D into Neuro2a cells or cortical neurons, and the neurite outgrowth was analyzed upon serum withdrawal (Fig. 5, F–H). The GFP-CA mutant was localized at the plasma membrane or nucleus similar to wild-type PLCδ3 in Neuro2a (Fig. 5F). In contrast, CA-R79D was mainly distributed in the nucleus (Fig. 5F). Noticeably, the CA mutant exerted a profound effect on neurite outgrowth upon serum withdrawal (Fig. 5, F and G). Exogenous PLCδ3 had a greater stimulatory effect on neurite outgrowth than control (Fig. 5G); however, expression of CA-R79D somewhat abolished the effect in the absence of serum, indicating that the activity and specific targeting of PLCδ3 to the plasma membrane are critical for neurite outgrowth. Similar effect of GFP-CA introduction on neuronal outgrowth was observed in cortical neurons at 3DIV (Fig. 5H). The profound effect of GFP-CA mutant on neurite outgrowth (1.9-fold, Fig. 5I) was almost proportional to the ratio in specific activity of the GFP-PLCδ3 mutants against GFP-PLCδ3 (1.8-fold), indicating that PLCδ3 activity is important for the regulation of neurite outgrowth in cortical neurons.

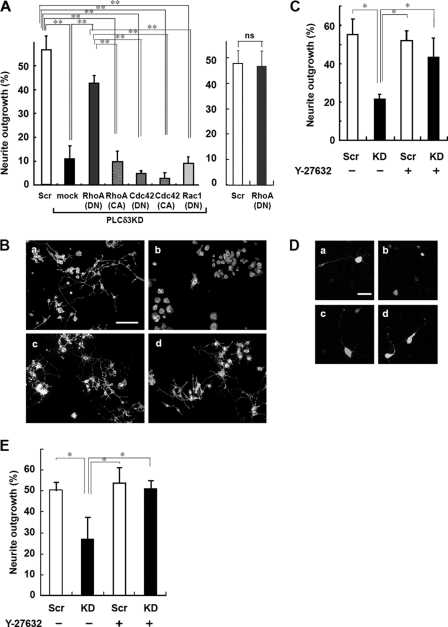

RhoA/Rho Kinase Signaling Is Located Downstream of PLCδ3 during Neurite Outgrowth

Several studies have indicated that the Rho GTPase family members are involved in neurite outgrowth via actin reorganization (1). To examine for a correlation between these small GTPases and PLCδ3 signaling in neuritogenesis, several CA or dominant negative mutants of Rho GTPase were introduced into PLCδ3KD cells. Interestingly, the RhoA-DN mutant nullified the inhibitory effects of PLCδ3 knockdown on neurite extension (Fig. 6A, left panel), although the RhoA-DN itself did not stimulate the outgrowth (Fig. 6A, right panel). The mutant RhoA-CA did not affect the inhibition caused by PLCδ3 knockdown. Similarly, mutant Rac1-DN, Cdc42-DN, or Cdc42-CA did not rescue the neurite outgrowth defect, suggesting that neither Rac1 nor Cdc42 is involved in this process. We could not evaluate the effect of mutant Rac1-CA because these mutant molecules caused a morphological abnormality that resulted in cell death. From these results, we predicted that PLCδ3 functions upstream of RhoA during neurite outgrowth in Neuro2a cells, because inhibition of RhoA promoted the extension only in the case for PLCδ3KD (right panel in Fig. 6A).

FIGURE 6.

RhoA/Rho kinase signaling is located downstream of PLCδ3 in neurite outgrowth. A, dominant negative RhoA rescues neurite outgrowth suppressed by PLCδ3KD in Neuro2a cells. PLCδ3 was knocked down with the vector carrying PLCδ3-targeting sequence, and the cells were subsequently transfected with GFP (mock), Myc-tagged dominant negative Rho family proteins (RhoA, Cdc42, and Rac1), and constitutively active RhoA or Cdc42, designated as DN and CA, respectively. The degree of neurite outgrowth was quantified, and the data represent the mean ± S.D. of three experiments. Tukey's test showed significant differences between control or myc-RhoA(DN)-transfected PLCδ3KD cells and PLCδ3KD cells introduced with other Rho family mutants (**, p < 0.01, left panel). The merely exogenous expression of myc-RhoA(DN) did not stimulate the neurite outgrowth (right panel). ns means not significant. B, treatment with the Rho kinase inhibitor Y-27632 reverts the inhibitory effects on neurite extension of Neuro2a cells by PLCδ3 knockdown. Cells were transfected with control pENTRTM/U6 vector (panels a and c) or PLCδ3-targeting shRNA vectors (panels b and d), and treated with (panels c and d) or without (panels a and b) 30 μm Y-27632, a specific Rho kinase inhibitor, for 48 h in DMEM without serum to induce neurite outgrowth. Scale bar, 100 μm. C, quantitative data of B were represented as the mean ± S.D. of three experiments. Tukey's test showed significant difference between untreated PLCδ3KD cells and other cells (*, p < 0.05). D, effects of Y-27632 on neurite outgrowth were analyzed in cortical neurons. Cells were transfected with control pENTRTM/U6 vector (panels a and c) or PLCδ3-targeting shRNA vectors (panels b and d), and treated with (panels c and d) or without (panels a and b) 25 μm Y-27632 for 24 h. Note that treatment of cortical neurons with 25 μm Y-27632 for 24 h reverted the inhibitory effect of PLCδ3 knockdown on neurite extension as observed in Neuro2a cells. Scale bar, 40 μm. E, data represent the mean ± S.D. of three experiments (n = 110). Tukey's test showed significant differences between control neurons and other cells (*, p < 0.05). Scr, scrambled.

To gain further insights into the contribution of the inhibition of RhoA signaling to neuritogenesis, Neuro2a cells or cortical neurons were treated with Y-27632, a specific inhibitor of Rho kinase that is known to act downstream of RhoA. In the case for Neuro2a, PLCδ3KD cells treated with 30 μm Y-27632 showed the same recovery of neurite outgrowth as that of the control (43% in Y-27632 treated cells versus 21% in untreated cells), although Y-27632 did not affect neurite outgrowth in the control cells (Fig. 6, B and C). Cortical neurons were also treated with 25 μm Y-27632 at 2DIV and incubated for 24 h. Treatment of control neurons with Y-27632 did not affect the neurite outgrowth at 3DIV (Fig. 6E). Although PLCδ3 KD caused significant inhibition of neurite outgrowth in the absence of the Rho kinase inhibitor, Y-27632 treatment reverted the inhibitory effect of PLCδ3KD on the outgrowth to the similar level of control neurons (Fig. 6, D and E). These results strongly suggest that RhoA/Rho kinase signaling is negatively regulated by PLCδ3 during neuritogenesis.

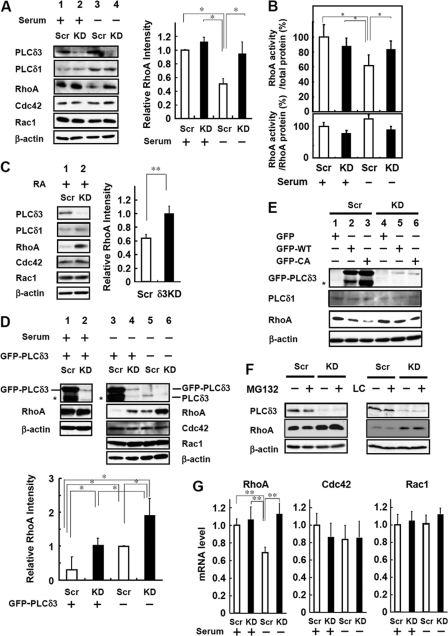

PLCδ3 Negatively Regulates RhoA Expression and Activity during Neuritogenesis

To elucidate how PLCδ3 negatively regulates Rho signaling, we focused on the expression levels of RhoA, Cdc42, and Rac1 in the control and PLCδ3KD cells. The expression level of RhoA was decreased by 50% in control cells by serum withdrawal (lane 1 versus lane 3 in Fig. 7A), although this decrease was not observed in the case of PLCδ3KD cells (lane 2 versus lane 4 in Fig. 7A). The expression levels of Cdc42 and Rac1 were neither changed during serum deprivation nor affected by PLCδ3 knockdown (Fig. 7A). To investigate the effects of PLCδ3 knockdown on Rho activity, we examined the activation of RhoA using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for GTP-bound RhoA. The levels of active RhoA were normalized to the total protein amounts. Upon serum withdrawal, the active RhoA level was decreased in control Neuro2a (100% in 1st column versus 62% in 3rd column in the case of scrambled oligonucleotide-transfected cells); however, the level was not changed in PLCδ3KD cells (87% in 2nd column versus 84% in 4th column) (Fig. 7B, upper panel). The level of GTP-bound RhoA was not affected by PLCδ3 knockdown in the presence of serum. We also assessed the ratio of RhoA activity to RhoA protein level and found no statistically significant effect of serum withdrawal or PLCδ3 knockdown on the activity (Fig. 7B, lower panel). These results strongly suggest that PLCδ3 lowers the total RhoA activity in control cells without modulating the Rho-GTP activity, thereby functioning in neuronal outgrowth. A similar reduction in RhoA amounts was obtained when the cells were differentiated by RA. The decrease in the expression level of RhoA was not detected in PLCδ3KD cells (Fig. 7C). It is interesting to note that reintroduction of exogenous GFP-PLCδ3 induced RhoA down-regulation in both the control (lane 3 versus lane 5 in Fig. 7D) and PLCδ3KD cells (lane 4 versus lane 6 in Fig. 7D) after serum withdrawal, and the expression level of RhoA was inversely proportional to the level of PLCδ3 level during differentiation (Fig. 7D). In contrast, neither Cdc42 nor Rac1 expression was affected by the introduction of PLCδ3. Interestingly, the exogenous expression of PLCδ3 did not induce RhoA down-regulation in undifferentiated cells (lane 1 versus lane 2 in Fig. 7D), suggesting that the combination of PLCδ3 with neurite extension signals is important for RhoA down-regulation (Fig. 7D). Exogenous PLCδ3-CA also down-regulated RhoA levels more than wild-type PLCδ3 upon serum withdrawal (Fig. 7E).

FIGURE 7.

PLCδ3 down-regulates RhoA expression in Neuro2a differentiation. A, PLCδ3 is involved in the decrease in RhoA expression by serum withdrawal. The control (lanes 1 and 3) or PLCδ3KD cells (lanes 2 and 4) were incubated in DMEM with (lanes 1 and 2) or without (lanes 2 and 4) serum for 48 h to induce neurite outgrowth, and the total amounts of Rac1, Cdc42, RhoA, PLCδ1, and PLCδ3 were analyzed by Western blotting. β-Actin was used for normalization. Quantification of RhoA proteins was performed from three experiments, and the data represent the average intensity ± S.D. Tukey's test showed significant difference between control cells incubated in DMEM without serum and other cells (**, p < 0.01). B, PLCδ3 is involved in reduced RhoA activity upon serum withdrawal. The level of active RhoA level is decreased in control cells by serum withdrawal, but PLCδ3 knockdown reverted the inhibitory effects of serum withdrawal on RhoA activation (upper panel). Cells were transfected with the control pENTRTM/U6 vector (Scr) or PLCδ3-targeting shRNA vectors (PLCδ3KD) and incubated for 48 h in the presence or absence of serum. The amount of active GTP-bound RhoA was quantified using the G-LISATM RhoA activation kit (Cytoskeleton Inc., Denver, CO) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The data represent the mean ± S.D. of three experiments. Dunnett's multiple comparison test showed significant differences between serum-depleted control cells and other cells (*, p < 0.05). The amount of RhoA protein was also analyzed, and the ratio of RhoA activity to RhoA protein level was calculated and presented as bar graph (lower panel). No significant difference was detected among the data. C, PLCδ3 is involved in the reduction of RhoA expression by treatment with RA. The control (lane 1) or PLCδ3KD cells (lane 2) were incubated with 20 μm RA in the presence of 2% serum for 24 h to induce neurite outgrowth, and the amounts of Rac1, Cdc42, RhoA, PLCδ1, and PLCδ3 were analyzed by Western blotting. RhoA protein levels were quantified from three experiments, and the data represent the average intensity ± S.D. *, p < 0.01 (Student's t test). D, exogenous PLCδ3 decreases the RhoA but not Cdc42 or Rac1 level upon serum withdrawal. Endogenous PLCδ3 was depleted by transient transfection with the PLCδ3-targeting shRNA vector (lanes 2, 4, and 6), and GFP-PLCδ3 was introduced into control (lanes 1 and 3) or PLCδ3KD cells (lanes 2 and 4). Note that exogenous GFP-PLCδ3 induced more significant RhoA down-regulation in both cells transfected with the control vector (lanes 3 and 5) and PLCδ3KD cells (lanes 4 and 6) by serum withdrawal. In contrast, GFP-PLCδ3 overexpression did not affect RhoA levels in the presence of serum (lanes 1 and 2). The asterisk indicates the degradation product of exogenous PLCδ3. Quantification of RhoA expression in the cells incubated in DMEM without serum was carried out from three experiments, and the data represent the average intensity ± S.D. *, p < 0.05 (Tukey's multiple comparison test). E, exogenous PLCδ3 CA mutant induced more significant RhoA down-regulation than WT in both transfected cells with the control (lanes 2 and 3) or PLCδ3KD vector (lanes 5 and 6) by serum withdrawal. F, proteasome inhibitors do not affect the stability of RhoA. The effect of proteasome inhibitors on RhoA stability was analyzed by Western blotting using Neuro2a cells treated with 20 μm MG132 for 6 h or 10 μm lactacystin (LC) for 4 h. Neither MG132 nor lactacystin affected the RhoA expression levels upon serum withdrawal. G, PLCδ3 specifically down-regulates RhoA upon serum withdrawal at the transcriptional level. RhoA, Rac1, Cdc42, or GAPDH mRNA levels were analyzed by qRT-PCR. β-Actin and GAPDH were used as controls, and quantification of mRNAs was performed in duplicate and repeated at least three times. The columns represent mean values, and the bars represent the S.D. Tukey's test showed significant differences between serum-depleted control and other groups (**, p < 0.01).

Several studies have indicated that ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation regulates the levels of the GTPase family molecules involved in cell polarity such as RhoA or Rap1b (22, 23). Smurf1, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, targets RhoA for degradation and generates a local asymmetry in GTPase activity, whereas Smurf1 does not influence a change in RhoA levels during RA-induced neurite outgrowth (22). To elucidate whether the proteolytic degradation machinery or post-translational down-regulation could be involved in the decrease in RhoA expression, the control or PLCδ3KD cells were treated with proteasomal inhibitors. Neither treatment with MG132 nor lactacystin, which is a more specific proteasomal inhibitor, resulted in RhoA accumulation in either the control or PLCδ3KD cells (Fig. 7F), whereas these reagents induced the accumulation of β-catenin, one of the proteasomal substrates (data not shown). This result suggests that RhoA is not targeted for ubiquitin-proteasomal degradation during serum withdrawal. Thus, we measured the mRNA levels of the Rho family using qRT-PCR analysis in control and PLCδ3KD cells. Following serum withdrawal, the RhoA mRNA levels were specifically decreased in the control cells, but this decrease was not observed in PLCδ3KD cells (Fig. 7G). PLCδ3 knockdown did not affect the levels of Cdc42 or Rac1 in differentiated cells. PLCδ3 knockdown in undifferentiated cells did not affect the mRNA levels of any of the members of the Rho GTPase family (Fig. 7G). These results strongly suggest that PLCδ3 negatively regulates RhoA expression at the transcriptional level by serum withdrawal.

DISCUSSION

PLCδ3 is enriched among PLCδ isozymes in neuronal tissues, including the cerebellum and cerebral cortex (Figs. 1, A and B, and 3A); therefore, we focused on the function of PLCδ3 in neurons. In this study, we demonstrated for the first time that PLCδ3 function is important for neurite formation in primary cerebellar granule cells (Fig. 1, B–E), outgrowth of axon or dendrites in cortical neurons (Fig. 3, B–E) in vitro, and the migration of cortical neurons in the developing brain in vivo (Fig. 2). Primary culture of granule cells is known to recapitulate the in vivo development of granule cells in the postnatal cerebellum. Several reports suggest that the spatial or temporal regulation of phosphoinositide metabolism could be critical for the formation of neural networks during cerebellar development (24, 25). Calcineurin is activated during the proliferation or differentiation of immature cerebellar granule neurons in vitro and in vivo (26). Cortical lamination in the cerebral cortex is organized by the sequential migration events of cortical neurons generating from the proliferating progenitor cells located in the ventricular zone, namely “inside-out pattern.” Although it was demonstrated that calcium waves propagate through radial glial cells by tightly modulating their cell cycle in ventricular zone proliferation, leading to the synchronous mobilization of migrating neurons in the neocortex (27), it seems to be unlikely that PLCδ3 is involved in the process in the ventricular zone. Radial glia has an important role in the cortical neuronal migration during the development of the cerebral cortical plate, and the neuronal migration is regulated by the following processes: generation of neuronal precursor and their initial migration, locomotion involving nucleokinesis, and the acquisition of appropriate laminar position (28, 29). Most of dissociated PLCδ3KD neurons exhibited lack of dendritic maturation (Fig. 3E). Axonal outgrowth of cortical neurons was also impaired by PLCδ3 knockdown treatment (Fig. 3, B–E), and PLCδ3 activity was required for the extension of cortical axon (Fig. 5, H and I). Therefore, it seems to be reasonable that PLCδ3KD could affect neuronal outgrowth processes, and PLCδ3 may function in the proper organization and development of the cerebral cortex or cerebellum by regulating Ca2+ signaling. The involvement of DAG and PKCδ activation in cortical migration has also been shown by knockdown experiments by in utero electroporation (30).

To gain further insights into the molecular mechanism of PLCδ3 in neuronal extension, we searched several neuronal cell lines expressing PLCδ3 and found that PLCδ3 is relatively abundant in Neuro2a cells (Fig. 4A). We showed that PLCδ3 is also indispensable for neurite outgrowth in Neuro2a neuroblastoma cells induced by serum withdrawal (Fig. 4, C and D) or treatment with RA (Fig. 4, E and F). RA secretion from the cortical meninges is known to regulate the generation of cortical neurons (31), suggesting that the involvement of PLCδ3 in neuronal extension could recapitulate the in vivo model of neurogenesis. It was noted that the H393A mutant did not compensate for the inhibitory effect of PLCδ3 knockdown on neurite outgrowth and induced formation of multiple protrusions in PLCδ3KD cells (Fig. 5D). In addition, PLCδ3-CA but not the CA-R79D mutant promoted neurite elongation (Fig. 5F). Similar effect of CA mutant on neuronal outgrowth was also observed in cortical neurons (Fig. 5, H and I), indicating that the catalytic activity of PLCδ3 is necessary for normal neurite outgrowth. Interestingly, PLCδ1 could not rescue the inhibition of neurite extension caused by PLCδ3 knockdown (Fig. 5C), indicating that merely the PI(4,5)P2 hydrolyzing activity of PLCδ3 is not sufficient to promote neurite outgrowth. An unknown PLCδ3 co-activator could account for the commitment to neurite polarity or elongation during neuronal differentiation.

It has been widely accepted that Rho family proteins have an important role in the neuronal differentiation during the brain development. The regulatory mechanism of Rho signaling seems to be divergent and cell type-specific, a growth factor or cell cycle regulator-dependent mechanism is integrated in their regulation for neuronal outgrowth (32, 33). Very close correlations between the Rho family of small GTPases and phosphoinositide metabolism have been reported. RhoA directly regulates the activity of phosphatidylinositol kinase type I (7), and a kinase-defective phosphatidylinositol kinase rescues the inhibitory effects of RhoA on neurite outgrowth (34). Therefore, we examined whether the Rho family is involved in neurite extension mediated by PLCδ3. Down-regulation of RhoA signaling upon differentiation in our system seems to be tightly regulated by PLCδ3 activity. First, the introduction of dominant negative RhoA showed a reversible effect on the neurite extension suppressed by PLCδ3 knockdown in Neuro2a. Expression of Rho-DN itself did not stimulate neuronal outgrowth in Neuro2a cells (Fig. 6A), although the inhibition of RhoA or Rho kinase activity itself has been known to stimulate axonal outgrowth in dorsal root ganglion neurons or some other neuronal cell lines such as PC-12 (1, 35). Second, treatment with Y-27632, a specific Rho kinase inhibitor, rescues neurite outgrowth inhibited by PLCδ3 knockdown in Neuro2a; however, it did not stimulate the outgrowth in control cells (Fig. 6, B and C). The reversible effect of Y-27632 on neurite outgrowth was also observed in the case for cortical PLCδ3KD neurons (Fig. 6, D and E). Third, PLCδ3 down-regulated RhoA levels upon serum withdrawal in Neuro2a and CA mutant down-regulated the RhoA protein levels more than wild-type PLCδ3 (Fig. 7, A and C–E). These results strongly support the idea that RhoA/Rho kinase signaling is specifically located downstream of PLCδ3 in neurite outgrowth and that this signaling is negatively regulated by PLCδ3 during neuritogenesis in the case for Neuro2a or cortical neurons.

The activation/inactivation of RhoA is regulated by a balance between RhoGAP and RhoGEF. Furthermore, the amount of the GTP-bound active form is considered to be an index of RhoA activation. We observed a decrease in the level of active RhoA levels in control Neuro2a cells upon serum withdrawal, whereas there was no decrease detected in PLCδ3KD cells (Fig. 7B). However, the ratio of RhoA activity to RhoA protein level was not significantly changed by either serum withdrawal or PLCδ3 knockdown, indicating that PLCδ3 regulates the total RhoA protein levels without modulating the RhoA activity through RhoGAP or RhoGEF.

More importantly, we show here that the protein level of RhoA is decreased via a mechanism mediated by PLCδ3 only during the differentiation process, i.e. as a result of serum withdrawal or RA treatment (Fig. 7, A and C). More direct evidence was obtained by the experiment in which exogenously expressed PLCδ3 down-regulated the level of RhoA when cells were starved of serum (Fig. 7D). It has been shown that expression level of RhoA in migrating neurons is down-regulated compared with premigratory cells in cortical ventricular zone (36) and lysophosphatidic acid, the major survival factor in serum, regulates Rho and Rho kinase activation through actin reorganization during neurite retraction (37). Loss of the lysophosphatidic acid receptor (LPA1) results in a disorganized brain structure (38); therefore, PLCδ3 could interfere with lysophosphatidic acid-mediated signaling by inhibiting downstream RhoA/Rho kinase signaling.

Because the decrease in RhoA expression during neurite outgrowth induced by serum withdrawal is not prevented by treatment with any proteasome inhibitor (Fig. 7F), PLCδ3 may be involved in a novel mechanism that down-regulates the level of RhoA in the case of RA or serum withdrawal-induced neuritogenesis. qRT-PCR analysis revealed that the amount of RhoA mRNA was negatively regulated at the transcriptional level by PLCδ3 when serum was depleted (Fig. 7G). These results indicate that PLCδ3 down-regulates RhoA/Rho kinase signaling, not via the modulation of Rho GTPase activity or proteasomal degradation. Considering the localization and PLC activity of the CA and CA-R79D mutant (Fig. 5F), normal neurite outgrowth may require RhoA down-regulation through regulated PLCδ3 activation and the generation of second messengers, namely IP3 and DAG at the plasma membrane upon serum withdrawal (supplemental Fig. 3). The treatment with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, an activator of conventional and novel protein kinase C or Ca2+-mobilizing reagents such as ionomycin or thapsigargin, a Ca2+-ATPase inhibitor irreversibly depleting intracellular Ca2+ store, induced RhoA down-regulation in both control and PLCδ3KD cells in the absence of serum (supplemental Fig. 3). These results suggest that both DAG and IP3 are important for the down-regulation of RhoA, thus promoting the neurite outgrowth.

In summary, we demonstrated for the first time that the PLCδ3 is involved in neuronal extension in vitro and in vivo. PLC activity is necessary for the commitment to neurite generation and outgrowth. In addition, our results show that PLCδ3 induces RhoA down-regulation; thus, it inhibits RhoA/Rho kinase signaling and promotes the extension of neurites. These findings further strengthen the notion that PI(4,5)P2/phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate metabolism is a critical determinant for neurite outgrowth and polarity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Shinpei Kobori for technical assistance. We thank Dr. Takai for the Myc-tagged RhoA, Rac1, and Cdc42 mutants.

This work was supported by a grant-in-aid for young scientists (Category B to Z. K.) and for general scientific research (to K. F.) and a High-Tech Research Center Project for Private Universities matching the fund subsidy from the Japan Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–3.

- PI(4,5)P2

- phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

- CA

- constitutively active

- DAG

- diacylglycerol

- IP3

- inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- PH domain

- pleckstrin homology domain

- PLCδ3

- phospholipase Cδ3

- KD

- knockdown

- DIV

- days in vitro

- EGFP

- enhanced GFP

- RA

- retinoic acid

- IP3

- inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- qRT

- quantitative PCR

- UCP

- upper cortical plate.

REFERENCES

- 1. Govek E. E., Newey S. E., Van Aelst L. (2005) Genes Dev. 19, 1–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kawauchi T., Chihama K., Nabeshima Y., Hoshino M. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 4190–4201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Garvalov B. K., Flynn K. C., Neukirchen D., Meyn L., Teusch N., Wu X., Brakebusch C., Bamburg J. R., Bradke F. (2007) J. Neurosci. 27, 13117–13129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moon S. Y., Zang H., Zheng Y. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 4151–4159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang H. R., Zhang Y., Ozdamar B., Ogunjimi A. A., Alexandrova E., Thomsen G. H., Wrana J. L. (2003) Science 302, 1775–1779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arimura N., Kaibuchi K. (2007) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 194–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Santarius M., Lee C. H., Anderson R. A. (2006) Biochem. J. 398, 1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fukami K., Inanobe S., Kanemaru K., Nakamura Y. (2010) Prog. Lipid Res. 49, 429–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Irino Y., Cho H., Nakamura Y., Nakahara M., Furutani M., Suh P. G., Takenawa T., Fukami K. (2004) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 320, 537–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ichinohe M., Nakamura Y., Sai K., Nakahara M., Yamaguchi H., Fukami K. (2007) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 356, 912–918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nakamura Y., Fukami K., Yu H., Takenaka K., Kataoka Y., Shirakata Y., Nishikawa S., Hashimoto K., Yoshida N., Takenawa T. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 2981–2991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nakamura Y., Ichinohe M., Hirata M., Matsuura H., Fujiwara T., Igarashi T., Nakahara M., Yamaguchi H., Yasugi S., Takenawa T., Fukami K. (2008) FASEB J. 22, 841–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fukami K., Nakao K., Inoue T., Kataoka Y., Kurokawa M., Fissore R. A., Nakamura K., Katsuki M., Mikoshiba K., Yoshida N., Takenawa T. (2001) Science 292, 920–923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fukami K., Yoshida M., Inoue T., Kurokawa M., Fissore R. A., Yoshida N., Mikoshiba K., Takenawa T. (2003) J. Cell Biol. 161, 79–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brummelkamp T. R., Bernards R., Agami R. (2002) Science 296, 550–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hicks S. N., Jezyk M. R., Gershburg S., Seifert J. P., Harden T. K., Sondek J. (2008) Mol. Cell 31, 383–394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kouchi Z., Shikano T., Nakamura Y., Shirakawa H., Fukami K., Miyazaki S. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 21015–21021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bito H., Furuyashiki T., Ishihara H., Shibasaki Y., Ohashi K., Mizuno K., Maekawa M., Ishizaki T., Narumiya S. (2000) Neuron 26, 431–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hama H., Hara C., Yamaguchi K., Miyawaki A. (2004) Neuron 41, 405–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xie Y., Hong Y., Ma X. Y., Ren X. R., Ackerman S., Mei L., Xiong W. C. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 2605–2611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yagisawa H., Okada M., Naito Y., Sasaki K., Yamaga M., Fujii M. (2006) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1761, 522–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bryan B., Cai Y., Wrighton K., Wu G., Feng X. H., Liu M. (2005) FEBS Lett. 579, 1015–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schwamborn J. C., Müller M., Becker A. H., Püschel A. W. (2007) EMBO J. 26, 1410–1422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 24. Nakanishi S., Okazawa M. (2006) J. Physiol. 575, 389–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Choi J. Y., Beaman-Hall C. M., Vallano M. L. (2004) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 287, C971–C980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sato M., Suzuki K., Yamazaki H., Nakanishi S. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 5874–5879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Weissman T. A., Riquelme P. A., Ivic L., Flint A. C., Kriegstein A. R. (2004) Neuron 43, 647–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Marín O., Rubenstein J. L. (2003) Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 26, 441–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cooper J. A. (2008) Trends Neurosci. 31, 113–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhao C. T., Li K., Li J. T., Zheng W., Liang X. J., Geng A. Q., Li N., Yuan X. B. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 21353–21358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Siegenthaler J. A., Ashique A. M., Zarbalis K., Patterson K. P., Hecht J. H., Kane M. A., Folias A. E., Choe Y., May S. R., Kume T., Napoli J. L., Peterson A. S., Pleasure S. J. (2009) Cell 139, 597–609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ahmed Z., Berry M., Logan A. (2009) Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 42, 128–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kawauchi T., Chihama K., Nabeshima Y., Hoshino M. (2006) Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 17–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yamazaki M., Miyazaki H., Watanabe H., Sasaki T., Maehama T., Frohman M. A., Kanaho Y. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 17226–17230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhang Z., Ottens A. K., Larner S. F., Kobeissy F. H., Williams M. L., Hayes R. L., Wang K. K. (2006) Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 11, 12–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ge W., He F., Kim K. J., Blanchi B., Coskun V., Nguyen L., Wu X., Zhao J., Heng J. I., Martinowich K., Tao J., Wu H., Castro D., Sobeih M. M., Corfas G., Gleeson J. G., Greenberg M. E., Guillemot F., Sun Y. E. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 1319–1324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hirose M., Ishizaki T., Watanabe N., Uehata M., Kranenburg O., Moolenaar W. H., Matsumura F., Maekawa M., Bito H., Narumiya S. (1998) J. Cell Biol. 141, 1625–1636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Contos J. J., Fukushima N., Weiner J. A., Kaushal D., Chun J. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 13384–13389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.