Abstract

β-Secretase (BACE1) is an attractive drug target for Alzheimer disease. However, the design of clinical useful inhibitors targeting its active site has been extremely challenging. To identify alternative drug targeting sites we have generated a panel of BACE1 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that interfere with BACE1 activity in various assays and determined their binding epitopes. mAb 1A11 inhibited BACE1 in vitro using a large APP sequence based substrate (IC50 ∼0.76 nm), in primary neurons (EC50 ∼1.8 nm), and in mouse brain after stereotactic injection. Paradoxically, mAb 1A11 increased BACE1 activity in vitro when a short synthetic peptide was used as substrate, indicating that mAb 1A11 does not occupy the active-site. Epitope mapping revealed that mAb 1A11 binds to adjacent loops D and F, which together with nearby helix A, distinguishes BACE1 from other aspartyl proteases. Interestingly, mutagenesis of loop F and helix A decreased or increased BACE1 activity, identifying them as enzymatic regulatory elements and as potential alternative sites for inhibitor design. In contrast, mAb 5G7 was a potent BACE1 inhibitor in cell-free enzymatic assays (IC50 ∼0.47 nm) but displayed no inhibitory effect in primary neurons. Its epitope, a surface helix 299–312, is inaccessible in membrane-anchored BACE1. Remarkably, mutagenesis of helix 299–312 strongly reduced BACE1 ectodomain shedding, suggesting that this helix plays a role in BACE1 cellular biology. In conclusion, this study generated highly selective and potent BACE1 inhibitory mAbs, which recognize unique structural and functional elements in BACE1, and uncovered interesting alternative sites on BACE1 that could become targets for drug development.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, Amyloid, Antibodies, Enzyme Inhibitors, Epitope Mapping, Amyloid β-peptide, β-secretase (BACE1)

Introduction

Alzheimer disease (AD)2 is the most common form of progressive dementia in the elderly population. Whereas several pathologies characterize this disease, amyloid plaques, composed of amyloid peptide, and the neuronal tangles, remain the hallmarks of AD brains. A wealth of evidence suggests that amyloid β peptide (Aβ) is central to AD pathogenesis (1, 2). Aβ is generated from sequential cleavage of amyloid precursor protein (APP) by β- and γ-secretase (3).

BACE1 has been identified as the β-secretase (4–8). It is a 501 amino acids containing type I membrane-bound aspartyl protease, presenting two active site motifs, D*TGS and D*SGT in its ectodomain. BACE1 belongs to the pepsin family and has a close homolog BACE2 (7). BACE1 is synthesized as a pro-enzyme in the endoplasmic reticulum, where it is acetylated (9) and glycosylated (10). During Golgi transit, BACE1 becomes deacetylated and mature N-glycosylated. Following pro-domain cleavage by furin or furin-like convertases in the trans-Golgi network (11), mature BACE1 exits the Golgi and is destined to the plasma membrane, from where it is re-internalized into endosomal compartments (12–14). BACE1 cleaves APP most prominently in early endosomes (15), where the acidic environment is optimal for its enzymatic activity. Blocking endocytosis significantly reduces Aβ generation (16, 17).

Knock-out of the BACE1 gene in mice abolished the generation of Aβ. Bace1−/− mice were viable and fertile (18–20), displaying some abnormalities including higher mortality rate in early life (21), hypomyelination (22, 23) as well as a schizophrenia-like phenotype (24). However, a partial reduction of BACE1 by RNA interference or by heterozygous knock-out was efficient in preventing amyloid pathology and cognitive deficits in transgenic AD mice (25, 26). Besides, crystal structures of BACE1 were resolved, facilitating inhibitor drug design (27). BACE1 is thus an attractive drug target for AD intervention.

Current BACE1 inhibitors have been mainly generated from rational design or fragment-based screening (28, 29). The development of an effective inhibitor drug, however, has been extremely challenging. BACE1 has an unusually large catalytic site (27) and shares similarities in inhibitor profiles with BACE2 and Cathepsin D (30, 31). Therefore, the design of a small inhibitor with high potency and selectivity is very difficult. Moreover, the molecular structures of many BACE1 inhibitors made them highly susceptible to the P-glycoprotein efflux transport system at the blood-brain-barrier (BBB), which consequently limits the bioavailability of drug inhibitors to target compartments in the CNS (32, 33).

There are seven loops and helices on the surface of the BACE1 ectodomain that structurally distinguish BACE1 from other aspartyl proteases (27). Among them, loops D, F, and helix A, are flanking the active-site cleft. Interestingly, loop F and helix A are highly flexible and disordered in all crystal structures (27, 34–37). They might be involved in substrate docking (37) or might affect the active site conformation (38). However, these unique insertions have not been exploited as alternative drug target sites.

In this work, we have generated monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) directed against human BACE1 that interfere with its activity in various assays. We have identified the epitopes targeted by these antibodies and characterized the function of the targeted domains by site-directed mutagenesis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Immunization and Hybridoma Generation

The immunogen human BACE1 ectodomain protein (amino acids 45–460) was purified from HEK293 cell culture by the Protein Service Facility (PSF), VIB, Belgium. Five 9-week-old Bace1−/− Bace2−/− knock-out mice (21) received four immunizations at 4-week intervals, with each immunization composed of one intraperitoneal injection of immunogen in 1:1 mixture with Freund's adjuvant. The first immunization contained 50 μg of immunogen emulsified in Freund's complete adjuvant, whereas all subsequent immunizations used 40 μg of immunogen in Freund's incomplete adjuvant. Serum antibodies were titrated by BACE1 ELISA 2 weeks after the final immunization. Two mice with the highest titers were chosen for generation of hybridomas. Three months after the final immunization, each mouse received one boost consisting of one intravenous injection of 30 μg of immunogen (diluted in sterile PBS) via the tail vein. Five days after the boost, mice were sacrificed, and spleens were isolated and fused with GM5426 myeloma cells at 4:1 ratio. In total, 200 million spleen cells were collected, mixed with 50 million myeloma cells and murine primary macrophages (obtained from the intraperitoneal lavages of five adult female balb/c mice). The cell mixture was plated out into twenty-seven 96-well plates. Hybridomas were first selected in HAT (Invitrogen) medium for 2 weeks and then in HT (Invitrogen) medium for another week. Cells were maintained in DMEM (invitrogen) supplemented with 15% FBS (Hyclone). More than 90% of the wells gave cell colonies following hybridoma selection.

BACE1 ELISA

ELISA screening for hybridoma clones was performed essentially as described in (39). Briefly, 96-well polyvinyl chloride plates (BD Falcon) were coated with 1 μg/ml purified BACE1 ectodomain protein overnight at 4 °C. Plates were blocked with 2% BSA for 1 h and incubated with hybridoma supernatants (50 μl per well for 2 h at room temperature). After washing, anti-mouse IgG-HRP (Innova Biosciences) was added to the ELISA plates at 1:5000 dilution in 2% BSA and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Plates were washed and developed with 0.2 mg/ml tetramethyl benzidine (Sigma) dissolved in 0.1 m NaAc, pH 4.9 supplemented with 0.03% H2O2. Reactions were stopped by adding 2 n H2SO4, and plates were immediately read on an ELISA reader at A450 nm.

BACE1 mcaFRET Assay

The assay was performed essentially as described in Ref. 40, and materials were provided by Eli Lilly. Briefly, hBACE1:Fc was diluted into 1 nm in reaction buffer (50 mm ammonium acetate pH 4.6, 1 mg/ml BSA and 0.6% Triton X-100). The FRET substrate (MCA)-S-E-V-N-L-D-A-E-F-R-K(Dnp)-R-R-R-R-NH2 was diluted into 125 μm in reaction buffer. 20 μl hybridoma supernatants (hybridoma screening) or mAb dilutions (dose-response curve for testing mAbs) were mixed with 30 μl hBACE1:Fc and 50 μl substrate in 96-well black polystyrene plates (Costar). The plates were read immediately for baseline relative fluorescence unit (RFU) signal by an EnVision Multilabel Reader (Perkin Elmer) at excitation wavelength 355 nm and emission wavelength 430 nm, and then incubated overnight in dark at room temperature. The plates were read again the following morning using the same reader protocol. The difference between end time RFU and baseline RFU represents the activity of BACE1. To determine the activity of BACE1 mutants, 1 nm purified enzyme was incubated with 30 μm FRET substrate in reaction buffer at 30 °C. The RFU was read at different time points: 0, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min. The time-dependence curve of RFU (-baseline) was in a linear range and the slope was used to present the initial rate for wild-type or mutant hBACE1:Fc toward the FRET peptide substrate.

BACE1 MBP-C125APPsw Assay

The assay was performed essentially as described in (5), and materials were provided by Eli Lilly. Briefly, hBACE1 (1–460):Fc was diluted into 10 nm in reaction buffer (50 mm ammonium acetate pH 4.6, 1 mg/ml BSA, and 1 mm Triton X-100). Substrate fusion protein of MBP and 125 amino acids of the C terminus of human APPsw was diluted into 50 nm in reaction buffer. 10 μl of test mAb was incubated with 25 μl of substrate and 15 μl of enzyme at 25 °C for 3 h. At the end of the incubation, the reaction mixture was diluted 5-fold in stop buffer (200 mm Tris pH 8.0, 6 mg/ml BSA and 1 mm Triton X-100). 50 μl of the diluted reaction mixture was then loaded on an ELISA plate pre-coated with anti-MBP antibody. The cleavage product MBP-C26sw was detected by a neo-epitope antibody against the BACE1 cleavage site. Purified MBP-C26sw was used to generate a standard curve. The amount of cleavage product represents the activity of BACE1.

Purification of hBACE1:Fc

The construct expressing hBACE1 (1–460) fused to human IgG1 Fc (hBACE1 1–460:Fc) was described previously (6). Mutations including Δloop F and Δhelix A were introduced into the original construct. Purification of wild-type or mutant hBACE1:Fc followed a protocol described previously (40). Protein purity was assessed by 4–12% Bis-Tris SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining. Aliquots of the enzyme were snap-frozen and stored at −80 °C.

Neuronal Assay

Primary mixed brain neurons were derived from E14 embryos from C57BL/6J mice as described previously (41). Generation of recombinant Semliki forest viruses (SFV) followed the protocol described previously (41). Neurons were cultured in 6-cm dishes (Nunc) and maintained in neurobasal medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with B27 (Invitrogen). 3-days cultured neurons were transfected with SFV expressing WT human APP695. Two hours after transfection, neurons were treated with test mAb diluted in fresh media for ∼16 h. Conditioned media were analyzed by Aβ ELISA (below) or Western blots using antibody WO2 (Genetics) for Aβ, 22C11 (Chemicon/Biognost) for total sAPP, or anti-sAPPβ (Covance) for sAPPβ. Cell extracts were analyzed by Western blots using antibody B63 (42) for full-length and C-terminal fragments of APP.

Stereotactic Injection and Brain Sample Analysis

Transgenic APPDutch mice (43) at 3 months-of-age were used for injection. mAb 1A11 or Mouse IgG1 Isotype Control (eBioscience) was stereotactically administered into the hippocampus and cortex (coordinates bregma −0.246 cm, lateral ±0.26 cm, depth −0.25 cm) using a Hamilton syringe 7001N. Mice were sacrificed 24 h after injection and brains were dissected to obtain an ∼1.5 mm-thick tissue around injection sites within the hippocampus and cortex. Brain tissues were extracted by sonication in 6 m guanidine/HCl in 50 mm Tris-HCl buffer pH 7.6 supplemented with complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche). The extracts were incubated for 1 h at 25 °C and then centrifuged at 70,000 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C. A fraction of the supernatants was diluted 12-fold and analyzed on Aβ ELISA plates. Meanwhile, a fraction of the supernatants was diluted 12-fold and subjected to immunoprecipitation followed by Western blot using antibody B63 for full-length and C-terminal fragments of APP.

Aβ ELISA

The concentration of Aβ1–40 or Aβ1–42 was determined by standard sandwich ELISAs using end-specific antibodies provided by Janssen Pharmaceutica. mAbs JRFcAβ40/28 and JRFcAβ42/26 recognizing the C terminus of Aβ species terminating at 40 or 42, respectively, were used as capturing antibodies. HRP-conjugated JRFAβN/25 recognizing the N-terminal 1–7 amino acids of human Aβ was used as detection antibody. Synthetic human Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 peptides were used to generate standard curves.

Epitope Mapping

BACE1 deletion mutants were generated by PCR amplification from human BACE1 cDNA and subcloned into a pGEX-4T-1 vector. All mutants were validated by DNA sequencing. GST-BACE1 fusion proteins were purified from BL21 (Novagen) bacterial cultures as described (42). The purified fusion proteins were subjected to 10% Bis-Tris SDS-PAGE and blotted with test mAbs.

Mutagenesis

All mutagenesis was performed using the QuickChange II XL Site-directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's instructions. All mutants were validated by DNA sequencing.

Fluorescence Microscopy

For hybridoma screening, HEK293 cells stably expressing human BACE1 were grown on 96-well plates coated with 0.2 mg/ml poly-l-lysine. Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100. After blocking the cells with 5% goat serum diluted in blocking buffer (PBS supplemented with 2% FBS, 2% BSA, and 0.2% gelatin) overnight at 4 °C, 50 μl of hybridoma supernatant was added to each well and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. Cells were then washed and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 goat-anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen) diluted in blocking buffer for 1 h at room temperature. After washing, 96-well plates were analyzed using an IN Cell Analyser 1000 (GE Healthcare).

For surface staining of fixed cells, HEK293 cells stably expressing human BACE1 were grown on coverslips, fixed and immunostained as described above. For surface staining of living cells, cells were grown on coverslips coated with 0.2 mg/ml poly-l-lysine, and were incubated with test mAb diluted in ice-cold DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS for 30 min at 4 °C. Cells were then washed and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 goat-anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen) diluted in fresh medium for 30 min at 4 °C. After staining, cells were washed and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. The coverslips were mounted on slides and sealed with nail polish. Immunofluorescent images were acquired on ace was examined with a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope.

RESULTS

Hybridoma Screening for BACE1 Inhibitory mAbs

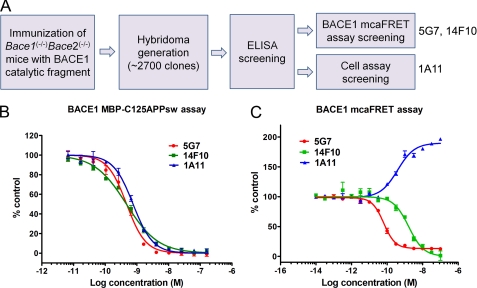

To generate mAbs for inhibition of BACE1 activity, we immunized Bace1−/−Bace2−/− knock-out mice (21) with part of the human BACE1 ectodomain (amino acids 46–460) containing the catalytic domain of this protease. Hybridomas (∼2700 clones) generated from the immunized mice were first screened in ELISA using immobilized BACE1. From 27 96-well plates, 400 wells were scored positive in this assay. The positive clones were then screened in a BACE1 mcaFRET enzymatic assay, resulting in six clones that displayed inhibitory activity. Only two clones, 5G7 and 14F10 were retrieved from subcloning and subjected to further characterization. In parallel, the positive clones from the ELISA assay were also screened in an immunofluorescence assay on fixed HEK293 cells that stably express BACE1 to identify antibodies that were able to immunolocalize membrane-bound BACE1. Twenty-five clones that gave the highest signals in the immunofluorescence assay were selected and further screened in a BACE1 cellular activity assay measuring sAPPβ secretion from SH-SY5Y stably transfected with human APP695. The supernatant of clone 1A11 inhibited sAPPβ secretion and was therefore selected as a potential BACE1 inhibitor (summarized in Fig. 1A).

FIGURE 1.

Hybridoma screening and characterization of mAbs in enzymatic assays. A, schematic representation of hybridoma screening for BACE1 inhibitory mAbs. Three candidates were selected for further analysis: mAbs 5G7 and 14F10 were identified from mcaFRET assay screening, mAb 1A11 was identified from cell assay screening. B, inhibition of BACE1 by the mAbs 5G7, 14F10, and 1A11 in BACE1 MBP-C125APPsw assay. Values are mean ± S.D.; n = 3. The substrate is a fusion protein of MBP and 125 amino acids of the C terminus of human APP containing the Swedish double mutation. The IC50 values for mAbs 5G7, 14F10, and 1A11 are 0.47 nm (95% CI: 0.41- 0.55 nm), 0.46 nm (95% CI: 0.42 - 0.52 nm), and 0.76 nm (95% CI: 0.67–0.85 nm), respectively. C, modulation of BACE1 activity in mcaFRET assay. Values are mean ± S.D.; n = 3. The substrate is a small FRET peptide MCA-SEVENLDAEFRK(Dnp)-RRRR-NH2. The IC50 (or EC50) values for 5G7, 14F10, and 1A11 are 0.06 nm (95% CI: 0.055–0.075 nm), 1.6 nm (95% CI: 1.2–2.1 nm), and 0.38 nm (95% CI: 0.27–0.55 nm), respectively.

mAbs 5G7, 14F10, and 1A11 Modulate BACE1 Activity in Cell-free Enzymatic Assays

We first characterized the three BACE1 inhibitory mAbs 5G7, 14F10 and 1A11 by an in vitro enzymatic assay, which uses the fusion protein maltose-binding protein (MBP) fused to APPsw 571–695 aa (MBP-C125APPsw) as a substrate. In this assay, all three mAbs inhibited BACE1 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1B). The IC50 (95% confidence interval) for the mAbs 5G7, 14F10, and 1A11 were 0.41 to 0.55 nm, 0.42 to 0.55 nm and 0.67 to 0.85 nm, respectively. We also tested the three mAbs in a BACE1 mcaFRET assay which uses a small FRET peptide substrate. The mAbs 5G7 and 14F10 inhibited BACE1 cleavage of this small FRET peptide in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1C). Unexpectedly, mAb 1A11 increased the activity of BACE1 2-fold toward the small substrate (Fig. 1C). The fact that mAb 1A11 modulated BACE1 activity depending on the substrate size, led us to conclude that this mAb binds to an allosteric site located near the active site of BACE1. Its binding thus activates the enzyme, but blocks the cleavage of big substrates, like APP, probably by steric hindrance.

mAb 1A11, but Not 5G7 or 14F10, Inhibits BACE1 Activity in Primary Cultured Neurons

We next investigated whether the mAbs 5G7, 14F10, and 1A11 inhibit BACE1 activity in neurons. Primary neurons derived from wild-type mice were infected with human APP using semliki forest virus (SFV) and then treated with 200 nm mAb 5G7, 14F10, or 1A11. A selective BACE1 inhibitor, compound 3 (44), was included as a positive control. After 16 h of treatment, conditioned media were subsequently analyzed by Western blot for secreted Aβ, sAPPβ, and sAPPtotal, whereas the cell extracts were analyzed by Western blot for full-length APP, C99, and C83. Neurons treated with mAb 1A11 markedly reduced secreted Aβ, sAPPβ, and C99, indicating a specific inhibition of BACE1 (Fig. 2A). Increases in C83 and sAPPtotal were observed when BACE1 was inhibited with mAb 1A11 or by compound 3 (Fig. 2A), suggesting a competition for substrate between the β- and the α-secretases (45–47). Interestingly, β-secretase inhibition also resulted in the increase of a longer CTF band appearing above C99. This longer CTF was reported before (48) as an alternative product of APP processing by an unknown secretase at the “δ” site, 12 residues from the N terminus of the Aβ domain (Thr-584 of APP695). However, when APP expression levels were lower, the longer CTF became neglectable even upon BACE1 inhibition (Fig. 2C). Unexpectedly, mAbs 5G7 and 14F10, which were potent BACE1 inhibitors in cell-free enzymatic assays, displayed no inhibitory effects on BACE1 in neuronal cultures (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

Inhibition of BACE1 by mAb 1A11 in primary neurons derived from wild-type mouse embryos. A, cultured neurons were infected with SFV expressing WT human APP695 and treated with 200 nm mAb 1A11, 5G7, or 14F10 (diluted in PBS). Compound 3 was used as a positive control (B1 inhibitor). Cell extracts or conditioned media were analyzed by Western blot (10% Bis-Tris SDS-PAGE) using antibodies 22C11 (sAPPtotal), B63 (full-length APP, C99, and C83), anti-sAPPβ (sAPPβ), and WO2 (Aβ). Notice the appearance of a δ-CTF (indicated with an arrow), see main text for the descriptions. B, cultured neurons infected with human APP695 were treated with decreasing concentrations of mAb 1A11 ranged from 20 to 0.16 nm. Conditioned media were analyzed by ELISAs for Aβlevels; Values are mean ± S.D.; n = 3. The EC50 values were estimated from the inhibition curves of Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 as 1.8 nm (95% IC: 1.5–2.2 nm) and 1.6 nm (95% IC: 1.4–1.8 nm), respectively, which are statistically not different. C, representative Western blots (10% Bis-Tris SDS-PAGE) showing the mAb 1A11 dose-dependent inhibition on sAPPβ and C99 generation.

We further established a dose inhibition curve for mAb 1A11 in primary neurons. Neurons were transfected with human APP using SFV and treated with decreasing concentrations of the mAb. Conditioned media were analyzed by ELISAs for Aβ, or by Western blot for sAPPβ, while cell extracts were analyzed by Western blot for full-length APP, C99, and C83. As evaluated from Aβ1–42 and Aβ1–40 levels, 10 nm mAb 1A11 inhibited ∼80% of BACE1 activity, and the EC50 was estimated as ∼1.8 nm (Fig. 2B). Correspondingly, a reduction of sAPPβ and C99 protein levels was observed in a mAb 1A11 concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2C).

mAb 1A11 Inhibits BACE1 Activity in the Hippocampus/Cortex of APP-overexpressing Mice

We next examined the in vivo inhibitory effects of mAb 1A11 using transgenic APP mice overexpressing APPDutch under the Thy-1 promoter (43). mAb 1A11 or a mouse isotype control IgG1 were stereotactically injected into the hippocampus/cortex of mouse brains. Brain samples were collected 24 h after injection for biochemical analysis. Total extracts were subjected to ELISAs for Aβ determination. Injection of mAb 1A11 led to significant decreases of Aβ1–40 (36.3%) and Aβ1–42 (31.4%) (Fig. 3, A and B). We also analyzed the brain extracts for full-length APP and CTFs by immunoprecipitation and Western blot. The immunoprecipitates were separated on 16% Tricine gels, and we were able to discriminate three major CTF bands. They represent phosphorylated forms of C99, C89 (generated from β′-site cleavage by BACE1, (6)), and C83 (Fig. 3D). There was also a faint band of non-phosphorylated C99 appearing between phosphorylated C99 and C89 (Fig. 3D). The separation pattern of these CTF bands was similar to previous reports (49, 50). After treatment with lambda protein phosphatase, the three major CTFs run at a higher mobility, i.e. non-phosphorylated forms of C99, C89, and C83 bands (Fig. 3E). Injection of mAb 1A11 significantly decreased C99 protein levels, whereas C83 levels remained unchanged (Fig. 3, C and D). We also observed a decrease in the C89 APP bands (49, 50) (Fig. 3D). This suggests a co-inhibition of BACE1 cleavage at E11 (β′-) site of APP by mAb 1A11 (6).

FIGURE 3.

Inhibition of BACE1 activity in APP-overexpressing mice by stereotactic administration of mAb 1A11 into the hippocampus/cortex. mAb 1A11 (4 μg) or mouse Isotype control IgG1 was injected into the hippocampus/cortex of APPDutch mice. Brain samples were collected 24 h after injection. Guanidine HCl extractions were analyzed by ELISAs for Aβ1–40 (A) and Aβ1–42 (B), or subjected to immunoprecipitation and Western blot using B63 antibody for full-length APP and its C-terminal fragments (CTFs). C99 and APP levels were quantified from Western blots and normalized to full-length APP expression levels (C). Values are mean ± S.E.; ***, p < 0.0001; t-test; n = 11 (control IgG) or n = 13 (mAb 1A11). D, representative Western blot (16% Tricine SDS-PAGE) showing the expression levels of full-length APP and the levels of different APP CTFs from mice injected with control IgG (lanes 1–4) or mAb 1A11 (lanes 5–8). E, immunoprecipitates of full-length APP and its CTFs from brain extractions of control APPDutch mice were treated without (lane 1) or with (lane 2) lambda protein phosphatase (LPP) and analyzed by Western blot using B63 antibody (16% Tricine SDS-PAGE). Please see text for the detailed description of the different APP CTF bands.

mAb 1A11 Binds to Unique Structures on BACE1: Loops D and F

We next mapped the binding epitope for mAb 1A11. A series of BACE1 fragments fused to an N-terminal GST tag were generated and purified from bacterial cultures. mAb 1A11 immunoreactivity to these deletion mutants was tested by Western blot (Fig. 4, A and B). The shortest fragment that reacted with mAb 1A11 was BACE1 314–460. Moreover, the immunoreactivity of mAb 1A11 to this fragment remained the same as that to full-length immunogen BACE1 46–460, indicating that the 1A11 epitope is fully located within the 314–460 BACE1 sequence (Fig. 4B). Because mAb 1A11 recognized BACE1 314–460 but not BACE1 329–460 (Fig. 4B), we concluded that the 15 amino acids within BACE1 314–329 were important for the binding of mAb 1A11. However, three other BACE1 fragments, 46–349, 46–364, and 46–390 containing the 314–329 BACE1 sequence, did not react with mAb 1A11 (Fig. 4B). All data together suggested that the epitope of mAb 1A11 was not linear. It has been previously reported that conformational epitopes can be detected by Western blot, probably because of epitope renaturation during or after the transfer of the protein to the blotting membrane (51). Thus, we speculate that mAb 1A11 may bind to a conformational epitope of BACE1.

FIGURE 4.

Epitope mapping of mAb 1A11. A, scheme for immunogen BACE1 46–460 (1) and the fragments (2–9). The numbers on the fragments represent the amino acids corresponding to full length human BACE1 protein. B, Western blot analysis (10% Bis-Tris SDS-PAGE) of mAb 1A11 against purified GST-BACE1 fragments. Immunogen BACE1 46–460 (1) and fragments BACE1 240–460 (4), 314–460 (8) are immunoreactive, whereas all the other fragments are not (upper panel). The anti-GST antibody recognizes all of these recombinant proteins (lower panel). C, scheme for loops D (residues 332–342) and F (residues 371–378) within BACE1 314–460 sequence (upper part). The three-dimensional structures of loops D and F were created using the PDB file 2G94 (lower part). D and E, mutagenesis of residues 332QAG334 to AGA (on loop D) or residues 376SQD378 to WAA (on loop F) abolishes immunoreactivity of mAb 1A11 to these GST-BACE1 mutants in Western blots.

To further investigate this epitope, we used a three-dimensional structure of the BACE1 ectodomain (PDB code 2G94) to define the protein regions that are close in space to the target sequence (residues 314–329). We found that residues 314–329 are directly linked to a protruding loop: loop D (amino acids 331–342), which is interacting with another loop: loop F (amino acids 371–378) (loops D and F were named in Ref. 27).

It is well known that surface protruding loops are highly immunogenic structures (52). Therefore, we hypothesized that the conformational epitope of 1A11 mAb is located at the interface between loops D and F. Mutations at the interface between loops D and F: 332QAG334 to AGA or 376SQD378 to WAA were introduced into the full length immunogen BACE1 46–460 (Figs. 4C and 6C). The mutants were purified from bacterial cultures and tested against the mAb 1A11 by Western blot. Both mutants reduced the immunoreactivity of mAb 1A11 to undetectable levels, as compared with wild-type BACE1 46–460 (Fig. 4, D and E).

FIGURE 6.

The binding epitope of mAb 5G7 is inaccessible from membrane-anchored BACE1 under native condition. A, cell surface staining of HEK293 cells stably expressing BACE1 using mAb 5G7 or 1A11. Staining was performed either with living cells at 4 °C (native condition) or after fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde. mAb 5G7 did not react to cell surface BACE1 under native condition. B, immunoprecipitation of membrane-bound BACE1 (total or cell surface after biotinylation) solublized in 1% CHAPSO, or shed BACE1 ectodomain from conditioned medium using mAb 5G7 or 1A1. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blots using either mAb 10B8 (epitope located within 46–240 aa of BACE1) for total BACE1 and shed BACE1 ectodomain, or using Streptavidin-HRP conjugate for cell surface BACE1. Notice that the blots do not show the relative amount of different forms of cellular BACE1. See Fig. 7 for the relative amount of shed and total BACE1. C, three-dimensional structure of BACE1 (created using PDB file 1FKN). Structures including loops D, F (residues 332–342, 371–378), helix A (residues 219–232), and helix 299–312 are indicated in pink, green, and yellow, respectively. mAbs 5G7 and 1A11 immunoreact with residues K299/E303/Q386 and 332QAG334/376SQD378, respectively.

To further validate these results, we introduced the same mutations into the full-length BACE1. BACE1 loop mutants were expressed in HEK293 cells overexpressing human APP695 (HEK293-APP695) and their cellular activities were determined. Both mutants were active in processing APP (data not shown), indicating that the proteins were properly folded. Cell extracts containing mutant or wild-type BACE1 were tested in immunoprecipitation assays using mAb 1A11. Both mutants failed to become immunoprecipitated by mAb 1A11, as compared with wild-type BACE1 (supplemental Fig. S1). It should be noticed that mAb 1A11 strongly reacted with BACE1 in immunoprecipitation assays, and relatively weak in Western blots, when compared with another BACE1-specific mAb 10B8 that strongly reacts with BACE1 in both assays (data not shown). This suggests that only a small fraction of BACE1 reconstitutes the mAb 1A11 epitope in Western blot assays and further supports the conformational nature of the recognized epitope.

Taken all together, our results indicate that mAb 1A11 binds to a conformational epitope comprising parts of loops D and F. Interestingly, both loops are unique characteristics of the BACE1 structure compared with BACE2 and other homologous aspartyl proteases (supplemental Fig. S2).

Loop F and Its Adjacent Structure Helix A Modulate BACE1 Activity

x-ray BACE1 structures have shown that loop F and its nearby helix A (amino acids 219–231) are highly flexible (27, 34–37). Furthermore, molecular dynamics simulations on BACE1 x-ray structures have shown that loop F and helix A compete with each other for interacting with the “10s loop” in the active-site pocket. Their outward movement affects the conformation of the “10s loop,” opening the S3 subpocket (36, 38). Here we hypothesized that the binding of mAb 1A11 to loop F modulates BACE1 activity through the 10s loop. To test our hypothesis, we analyzed the contribution of loop F to BACE1 activity by mutagenesis studies, and the nearby structure helix A was included in this analysis (the structures are indicated in the three-dimensional image of BACE1, see Fig. 6C). We generated Δloop F and Δhelix A deletion mutants, in which residues 371EDVATSQD378 and 219GFPLNQSEVLASVG232 were replaced by EGS and GAG short linkers, respectively. These Δloop F and Δhelix A mutants remain active in the cleavage of APP when expressed in HEK293-APP695 cells. No differences in protein maturation were observed when compared with wild-type BACE1, indicating that the mutants were properly folded and their cellular trafficking was not affected by the deletions (data not shown). We then purified soluble wild-type and mutant BACE1 via a C-terminal fused IgG Fc polypeptide from mammalian cell cultures. The concentration of the purified enzymes was determined by Western blot (supplemental Fig. S3). Next, we determined the enzymatic activity of the mutants by mcaFRET and MBP-C125APPsw assays. As compared with wild-type BACE1, Δloop F mutant reduced the enzymatic activity by ∼30% in both assays; whereas Δhelix A mutant increased BACE1 activity approximately two to 3-fold (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that both loop F and helix A play indeed a functional role in BACE1 activity.

FIGURE 5.

Enzymatic activities of purified BACE1 mutants. A, representative Coomassie staining (4–12% Bis-Tris SDS-PAGE) of the WT, Δhelix A, and Δloop F mutant BACE1:Fc (∼97 kDa) purified from HEK293 cell cultures. B, initial rates were determined for WT and mutant BACE1. Substrate concentrations used in mcaFRET assay and MBP-C125APPsw assays were 30 μm and 50 nm, respectively. Values are mean ± S.E.; n = 4; ***, p < 0.0001; Paired t-test.

mAb 5G7 Binds to Helix 299–312 on the Surface of BACE1, and This Epitope Is Inaccessible When BACE1 Is Membrane-anchored

The inhibition of BACE1 activity in primary neurons by mAb 1A11 indicated that the cleavage of APP by BACE1 can be efficiently blocked by specific mAbs. Interestingly, mAb 5G7, which appeared as a potent BACE1 inhibitor in enzymatic assays (Fig. 1, B and C), had no inhibitory effect on BACE1 activity in primary neurons (Fig. 2A). We speculated that the 5G7 mAb does not bind to BACE1 at the plasma membrane. We tested the possibility by cell surface staining using HEK293 cells stably expressing BACE1. Under native conditions, cell surface staining with this mAb gave no detectable fluorescent signal, while staining with the positive control mAb 1A11 showed a strong fluorescence signal (Fig. 6A) indicating the presence of BACE1 at the cell surface of those cells. Intriguingly, when cells were stained after fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde, the mAb 5G7 epitope became available, resulting in a strong cell surface staining signal (Fig. 6A). We also compared the staining pattern of 5G7 or 1A11 in the BACE1 stable expressing HEK293 cells after permeablization, both mAbs show colocalization with a commercial anti-BACE1 pAb and an endosome marker EEA1 (supplemental Fig. S4).

Both mAbs 5G7 and 1A11 recognized total membrane-bound or cell surface biotinylated BACE1 in immunoprecipitation assays after solubilization in 1% CHAPSO (Fig. 6B). Moreover, both antibodies recognized the shed BACE1 ectodomain from conditioned media under native conditions (Fig. 6B). Taking all evidence together, our results indicate that mAb 5G7 binds to an epitope that is exposed on secreted, soluble native BACE1 but is hidden when BACE1 is plasma membrane-anchored.

We further investigated the binding epitope for this antibody. As revealed by epitope mapping, using a similar strategy as for mAb 1A11 (supplemental Fig. S5), mAb 5G7 binds to a conformational epitope, which mainly consists of Lys299, Glu303, and Gln386. Site-directed mutagenesis of these amino acids strongly impaired the 5G7 immunoreactivity to BACE1 in immunoprecipitation without affecting the folding or maturation of the protease (supplemental Fig. S5D). We concluded then that the epitope is partially located on helix 299–312 located at the protein surface of BACE1 (Fig. 6C).

Mutagenesis of Helix 299–312 Markedly Reduced the Ectodomain Shedding of BACE1

BACE1 and BACE2 share high similarity in protein folding and helix 299–312 is a conserved structure between these two homologues. However, the exposed surfaces of these helices (BACE1 299–312 aa, BACE2 313–326 aa) differ at the amino acids level (Fig. 7A). To study the function of this helix in BACE1 without destroying the secondary structure, we replaced five or three exposed amino acids into the corresponding residues of BACE2. The helix 299–311 mutant (K299Q/E303D/K307E/K310A/A311R) and helix 307–311 mutant (K307E/K310A/A311R) were first expressed in HEK293 cells. The cell extracts were checked by Western blot for protein expression using a BACE1-specific mAb (mAb 10B8, whose epitope is located within BACE1 46–240 aa). Both mutants were expressed similar to wild-type BACE1, despite slightly decreases in mature BACE1 levels (Fig. 7B). We also analyzed the conditioned media by immunoprecipitation and Western blot for the shed BACE1 ectodomain using the same mAb 10B8. Interestingly, helix 299–311 mutant completely abolished the ectodomain shedding of BACE1 to an undetectable level (Fig. 7B), whereas helix 307–311 mutant markedly reduced the amounts of shed BACE1 ectodomain in comparison to wild-type BACE1 (Fig. 7B). This result was confirmed by using alternative BACE1-specific mAb 1A11 in immunoprecipitation demonstrating the absence and decrease, respectively, of secreted BACE1 from the mutants (data not shown).

FIGURE 7.

Mutagenesis of helix 299–312 reduced shedding of BACE1 ectodomain from HEK293 cells. A, protein sequence alignment of helix 299–312 on BACE1 and corresponding helix 313–326 on BACE2. B, wild-type BACE1 or mutants of the helix: M1 (K299/E303/K307/K310/A311 to Q/D/E/A/R) and M2 (K307/K310/A311 to E/A/R) were expressed in HEK293 cells. Conditioned media were analyzed by immunoprecipitation and Western blots for shed BACE1 ectodomain using mAb 10B8 (epitope located within 46–240 aa of BACE1); Cell extracts (10%) were loaded on the same blot for detection of total BACE1. The upper and lower panels are short and long exposure of the blot, respectively.

To prove that the marked reduction of BACE1 ectodomain shedding is not simply due to imparted protein maturation or stability, we performed pulse-chase experiments. HEK293 cells transfected with wild-type or mutant BACE1 were metabolically labeled with [35S]methionine/cysteine and chased in non-radioactive media for various time periods up to 24 h. Both helix mutants mature with similar kinetics as the wild-type BACE1, as indicated by the molecular mass shift from ∼55 to ∼66 kDa (Fig. 8). Besides, the turnover of BACE1 was not affected in these two mutants compared with wild-type BACE1 (Fig. 8).

FIGURE 8.

Maturation and turnover of BACE1 mutants. HEK293 cells expressing wild-type BACE1, helix 307–311 mutant (K307/K310/A311 to E/A/R) or helix 299–311 mutant (K299/E303/K307/K310/A311 to Q/D/E/A/R) were pulse-labeled for 10 min with [35S]methionine/cysteine and chased in growth medium for the indicated amount of time. BACE1 was immunoprecipitated with mAb 10B8 (epitope located within 46–240 aa of BACE1) and detected by autoradiography (A). Plots (B–D) showing the kinetics of BACE1 maturation and turnover. Immature, mature and total BACE1 are presented as a percentage of maximum total BACE1. Plot (E) compares the turnover of mature BACE1 between wild-type BACE1 and helix mutants. Mature BACE1 is presented as a percentage of maximum wild-type mature BACE1. The plots show the results of two independent experiments.

We also checked the enzymatic activities of these two mutants by expressing them in HEK293-APP695 cells. We found no apparent change in the cleavage of APP as compared with wild-type BACE1 (data not shown). This is in line with published data that inhibition of BACE1 shedding does not affect APP processing by BACE1 under overexpressing conditions (53).

DISCUSSION

BACE1 is reported to traffic to the cell surface (12) and to cleave APP after its internalization into the endosomal compartment (16, 17). During its long half-life (12), BACE1 is assumed to cycle between the trans-Golgi network, endosomes and cell surface for several rounds (13). A previous study reported that anti-BACE1 antibodies were rapidly taken up by HeLa cells overexpressing BACE1, suggesting that specific antibodies may undergo co-internalization with cell surface BACE1 (54). In this work, we tested the internalization of mAb 1A11 in primary hippocampal neurons and observed partial colocalization of internalized mAb 1A11 with acidic cellular compartments of wild-type neurons (supplemental Fig. S6). In contrast, uptake of mAb 1A11 in Bace1−/− neurons was neglectable (supplemental Fig. S6), indicating that BACE1 is guiding the antibody internalization process. The potent inhibition of BACE1 by mAb 1A11 in primary neurons (up to ∼80% inhibition, EC50 ∼1.8 nm) clearly shows that endogenous BACE1 can be effectively inhibited by specific mAbs. In contrast to the conception that BACE1 inhibitors should be cell-permeable in order to reach the processing compartments, i.e. the endosomes (28, 55), this work shows that antibody inhibitors, which are cell-impermeable and target BACE1 most likely via the cell surface, are sufficient for inhibition of BACE1 cleavage of APP.

Under our experimental conditions, we also detected an increase of a longer form of APP C-terminal fragment δ-CTF (48) upon BACE1 inhibition by either mAb 1A11 or inhibitor compound 3 (Fig. 2A). We are not aware of any potential risk that could be associated with the accumulation of such an aberrant CTF. As this longer CTF was not observed at endogenous levels of APP expression, we consider the δ-CTF of minor concern in the context of BACE1 therapeutic inhibition.

The mAb 1A11 inhibitor binds to unique structures on BACE1, namely the adjacent loops D and F (27). These two loop structures are absent in other aspartyl proteases, like pepsin and cathepsin D (27). BACE2, the closest homologue of BACE1, is the only known aspartyl protease that shares similar loop structures (supplemental Fig. S2A). However, the protein sequence of loops D and F completely differs between BACE1 and BACE2 (supplemental Fig. S2B). In fact, replacing BACE1 loop F with the corresponding BACE2 sequence abolished mAb 1A11 immunoreactivity (data not shown). We also tested the specificity of mAb 1A11 in immunoblot using mouse brain extracts, this mAb was highly specific to BACE1 as it reacted strongly to extracts from wild-type mouse brain but not to Bace1(−/−) mouse brain (supplemental Fig. S7). Taken together, mAb 1A11 is considered as a highly selective BACE1 inhibitor.

Interestingly, the binding of mAb 1A11 increases BACE1 activity toward a small FRET peptide substrate 2-fold, implying that BACE1 activity can be modulated allosterically. The interface between loops D and F is therefore revealed as a novel allosteric site on BACE1. Loop F is highly flexible and was reported to compete with its nearby helix A for interaction with the “10s loop” in the catalytic center. In this work, we showed that the purified Δloop F and Δhelix A mutants had opposite effects on BACE1 activity: Δloop F decreased BACE1 activity with 30%, whereas Δhelix A increased BACE1 activity two to 3-fold. Taken together, these data suggest the unique structures loop D, F, and helix A are functional in modulating BACE1 activity. Further work should investigate whether these regions can be targeted with small drug like compounds for BACE1 inhibition.

Another interesting finding is the binding epitope for mAb 5G7 within helix 299–312 on the surface of BACE1. According to our results, this epitope is inaccessible when BACE1 is membrane-anchored, and becomes available once BACE1 is secreted into the growth medium. Four lysine residues are exposed on this helix 299–312; three of them undergo acetylation in the endoplasmic reticulum (9), implicating that neutralizing these positively charged residues might be important for the stabilization of BACE1 protein structure during maturation (9, 56). After deacetylation in the Golgi, these lysine residues might turn to interact with other proteins or lipids. Mutagenesis of this helix 299–312, which includes several of these lysine residues: K299Q/E303D/K307E/K310A/A311R or K307E/K310A/A311R, strongly impaired the shedding of BACE1 ectodomain. This effect was not due to gross differences in cellular localization, as both mutants were located at the plasma membrane and other cellular compartments, similar to wild-type BACE1 (data not shown). It was reported that mutagenesis of the S-palmitoylation sites (C478A/C482A/C485A) in the cytoplasmic tail of BACE1, significantly increased the shedding of BACE1 ectodomain (57), suggesting that membrane microdomain distributions might affect BACE1 shedding. Here we speculate that helix 299–312 mutants might block BACE1 shedding by, for example, impairing its interaction with a “binding partner”, which directs BACE1 to the unknown BACE1 sheddase (53). Further study will investigate this possibility and try to understand how helix 299–312 regulates BACE1.

To date, almost all small inhibitors for BACE1 target the enzyme catalytic center. Only recently a non-competitive inhibitor targeting the transmembrane domain of BACE1 was reported (58). In this work, the potent mAb inhibitors broadened the potential drug targeting region to structures exposed at the protein surface of the BACE1 ectodomain. While we considered the use of mAb 1A11 for peripheral intravenous administration to block BACE1 in the brain, in analogy with passive immunization strategies to lower Aβ load in the CNS (59, 60), we failed to inhibit BACE1 activity in mouse brain significantly by this route (data not shown). It is known that the BBB limits the effectiveness of most CNS drug candidates including peptides and antibodies. However, it should be noted that CNS drug delivery systems are currently under intensive and continuous investigation, and that it might be possible in the future to administrate antibody drugs with such novel systems (61, 62). In fact, for many brain diseases, including brain tumors, multiple sclerosis, and HIV encephalopathy, antibodies are promising drug candidates. The 1A11 mAb generated in this work, thus, might become a viable option for BACE1 inhibition in vivo once effective CNS delivery systems are established.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Veerle Baert and Wendy Vermeire for technical support in generating hybridomas, Phil Szekeres, Richard Brier, and Patricia Gonzalez-DeWhitt for input concerning the BACE1 enzymatic assays and cellular assays, to Ronald DeMattos, Margaret Racke, Zhixiang Yang, and Len Boggs for intravenous infusion studies with mAb 1A11, to Mathias Jucker for providing APPDutch mice and critical reading of the manuscript, and to Robert Vassar for providing the BACE1-(1–460):Fc construct.

This work was supported by VIB, Eli Lilly, FWO, SA0-FRMA (grant cycle 2008/2009), the Federal Office for Scientific Affairs, Belgium (IUAP P6/43/), a Methusalem grant of the KULeuven and the Flemish Government, and Memosad (FZ-2007-200611) of the European Union.

This paper is dedicated to the memory of Anna Vanluffelen.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S7.

- AD

- Alzheimer disease

- Aβ

- amyloid-β

- APP

- amyloid precursor protein

- BACE1

- β-site APP-cleaving enzyme 1

- mAb

- monoclonal antibody

- MBP

- maltose-binding protein

- CNS

- central nervous system

- BBB

- blood-brain-barrier

- aa

- amino acids

- RFU

- relative fluorescence unit.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hardy J., Selkoe D. J. (2002) Science 297, 353–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Golde T. E., Dickson D., Hutton M. (2006) Curr. Alzheimer Res. 3, 421–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Selkoe D. J. (2001) Physiol. Rev. 81, 741–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hussain I., Powell D., Howlett D. R., Tew D. G., Meek T. D., Chapman C., Gloger I. S., Murphy K. E., Southan C. D., Ryan D. M., Smith T. S., Simmons D. L., Walsh F. S., Dingwall C., Christie G. (1999) Mol. Cell Neurosci. 14, 419–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sinha S., Anderson J. P., Barbour R., Basi G. S., Caccavello R., Davis D., Doan M., Dovey H. F., Frigon N., Hong J., Jacobson-Croak K., Jewett N., Keim P., Knops J., Lieberburg I., Power M., Tan H., Tatsuno G., Tung J., Schenk D., Seubert P., Suomensaari S. M., Wang S., Walker D., Zhao J., McConlogue L., John V. (1999) Nature 402, 537–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vassar R., Bennett B. D., Babu-Khan S., Kahn S., Mendiaz E. A., Denis P., Teplow D. B., Ross S., Amarante P., Loeloff R., Luo Y., Fisher S., Fuller J., Edenson S., Lile J., Jarosinski M. A., Biere A. L., Curran E., Burgess T., Louis J. C., Collins F., Treanor J., Rogers G., Citron M. (1999) Science 286, 735–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yan R., Bienkowski M. J., Shuck M. E., Miao H., Tory M. C., Pauley A. M., Brashier J. R., Stratman N. C., Mathews W. R., Buhl A. E., Carter D. B., Tomasselli A. G., Parodi L. A., Heinrikson R. L., Gurney M. E. (1999) Nature 402, 533–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lin X., Koelsch G., Wu S., Downs D., Dashti A., Tang J. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 1456–1460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Costantini C., Ko M. H., Jonas M. C., Puglielli L. (2007) Biochem. J. 407, 383–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Charlwood J., Dingwall C., Matico R., Hussain I., Johanson K., Moore S., Powell D. J., Skehel J. M., Ratcliffe S., Clarke B., Trill J., Sweitzer S., Camilleri P. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 16739–16748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Creemers J. W., Ines Dominguez D., Plets E., Serneels L., Taylor N. A., Multhaup G., Craessaerts K., Annaert W., De Strooper B. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 4211–4217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huse J. T., Pijak D. S., Leslie G. J., Lee V. M., Doms R. W. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 33729–33737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Walter J., Fluhrer R., Hartung B., Willem M., Kaether C., Capell A., Lammich S., Multhaup G., Haass C. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 14634–14641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yan R., Han P., Miao H., Greengard P., Xu H. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 36788–36796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rajendran L., Honsho M., Zahn T. R., Keller P., Geiger K. D., Verkade P., Simons K. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 11172–11177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Koo E. H., Squazzo S. L. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 17386–17389 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Carey R. M., Balcz B. A., Lopez-Coviella I., Slack B. E. (2005) BMC Cell Biol. 6, 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cai H., Wang Y., McCarthy D., Wen H., Borchelt D. R., Price D. L., Wong P. C. (2001) Nat. Neurosci. 4, 233–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Luo Y., Bolon B., Kahn S., Bennett B. D., Babu-Khan S., Denis P., Fan W., Kha H., Zhang J., Gong Y., Martin L., Louis J. C., Yan Q., Richards W. G., Citron M., Vassar R. (2001) Nat. Neurosci. 4, 231–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Roberds S. L., Anderson J., Basi G., Bienkowski M. J., Branstetter D. G., Chen K. S., Freedman S. B., Frigon N. L., Games D., Hu K., Johnson-Wood K., Kappenman K. E., Kawabe T. T., Kola I., Kuehn R., Lee M., Liu W., Motter R., Nichols N. F., Power M., Robertson D. W., Schenk D., Schoor M., Shopp G. M., Shuck M. E., Sinha S., Svensson K. A., Tatsuno G., Tintrup H., Wijsman J., Wright S., McConlogue L. (2001) Hum. Mol. Genet 10, 1317–1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dominguez D., Tournoy J., Hartmann D., Huth T., Cryns K., Deforce S., Serneels L., Camacho I. E., Marjaux E., Craessaerts K., Roebroek A. J., Schwake M., D'Hooge R., Bach P., Kalinke U., Moechars D., Alzheimer C., Reiss K., Saftig P., De Strooper B. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 30797–30806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hu X., Hicks C. W., He W., Wong P., Macklin W. B., Trapp B. D., Yan R. (2006) Nat. Neurosci. 9, 1520–1525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Willem M., Garratt A. N., Novak B., Citron M., Kaufmann S., Rittger A., DeStrooper B., Saftig P., Birchmeier C., Haass C. (2006) Science 314, 664–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Savonenko A. V., Melnikova T., Laird F. M., Stewart K. A., Price D. L., Wong P. C. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 5585–5590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Singer O., Marr R. A., Rockenstein E., Crews L., Coufal N. G., Gage F. H., Verma I. M., Masliah E. (2005) Nat. Neurosci. 8, 1343–1349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McConlogue L., Buttini M., Anderson J. P., Brigham E. F., Chen K. S., Freedman S. B., Games D., Johnson-Wood K., Lee M., Zeller M., Liu W., Motter R., Sinha S. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 26326–26334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hong L., Koelsch G., Lin X., Wu S., Terzyan S., Ghosh A. K., Zhang X. C., Tang J. (2000) Science 290, 150–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Silvestri R. (2009) Med. Res. Rev. 29, 295–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Erlanson D. A., McDowell R. S., O'Brien T. (2004) J. Med. Chem. 47, 3463–3482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Turner R. T., 3rd, Loy J. A., Nguyen C., Devasamudram T., Ghosh A. K., Koelsch G., Tang J. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 8742–8746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Turner R. T., 3rd, Koelsch G., Hong L., Castanheira P., Ermolieff J., Ghosh A. K., Tang J. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 10001–10006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mahar Doan K. M., Humphreys J. E., Webster L. O., Wring S. A., Shampine L. J., Serabjit-Singh C. J., Adkison K. K., Polli J. W. (2002) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 303, 1029–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Meredith J. E., Jr., Thompson L. A., Toyn J. H., Marcin L., Barten D. M., Marcinkeviciene J., Kopcho L., Kim Y., Lin A., Guss V., Burton C., Iben L., Polson C., Cantone J., Ford M., Drexler D., Fiedler T., Lentz K. A., Grace J. E., Jr., Kolb J., Corsa J., Pierdomenico M., Jones K., Olson R. E., Macor J. E., Albright C. F. (2008) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 326, 502–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hong L., Tang J. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 4689–4695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hong L., Turner R. T., 3rd, Koelsch G., Shin D., Ghosh A. K., Tang J. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 10963–10967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Patel S., Vuillard L., Cleasby A., Murray C. W., Yon J. (2004) J. Mol. Biol. 343, 407–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Turner R. T., 3rd, Hong L., Koelsch G., Ghosh A. K., Tang J. (2005) Biochemistry 44, 105–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gorfe A. A., Caflisch A. (2005) Structure 13, 1487–1498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Binder L. I., Frankfurter A., Rebhun L. I. (1986) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 466, 145–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yang H. C., Chai X., Mosior M., Kohn W., Boggs L. N., Erickson J. A., McClure D. B., Yeh W. K., Zhang L., Gonzalez-DeWhitt P., Mayer J. P., Martin J. A., Hu J., Chen S. H., Bueno A. B., Little S. P., McCarthy J. R., May P. C. (2004) J. Neurochem. 91, 1249–1259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Annaert W. G., Levesque L., Craessaerts K., Dierinck I., Snellings G., Westaway D., George-Hyslop P. S., Cordell B., Fraser P., De Strooper B. (1999) J. Cell Biol. 147, 277–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Annaert W. G., Esselens C., Baert V., Boeve C., Snellings G., Cupers P., Craessaerts K., De Strooper B. (2001) Neuron 32, 579–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Herzig M. C., Winkler D. T., Burgermeister P., Pfeifer M., Kohler E., Schmidt S. D., Danner S., Abramowski D., Stürchler-Pierrat C., Bürki K., van Duinen S. G., Maat-Schieman M. L., Staufenbiel M., Mathews P. M., Jucker M. (2004) Nat. Neurosci. 7, 954–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Stachel S. J., Coburn C. A., Steele T. G., Jones K. G., Loutzenhiser E. F., Gregro A. R., Rajapakse H. A., Lai M. T., Crouthamel M. C., Xu M., Tugusheva K., Lineberger J. E., Pietrak B. L., Espeseth A. S., Shi X. P., Chen-Dodson E., Holloway M. K., Munshi S., Simon A. J., Kuo L., Vacca J. P. (2004) J. Med. Chem. 47, 6447–6450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Checler F. (1995) J. Neurochem. 65, 1431–1444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hussain I., Hawkins J., Harrison D., Hille C., Wayne G., Cutler L., Buck T., Walter D., Demont E., Howes C., Naylor A., Jeffrey P., Gonzalez M. I., Dingwall C., Michel A., Redshaw S., Davis J. B. (2007) J. Neurochem. 100, 802–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sankaranarayanan S., Price E. A., Wu G., Crouthamel M. C., Shi X. P., Tugusheva K., Tyler K. X., Kahana J., Ellis J., Jin L., Steele T., Stachel S., Coburn C., Simon A. J. (2008) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 324, 957–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Simons M., de Strooper B., Multhaup G., Tienari P. J., Dotti C. G., Beyreuther K. (1996) J. Neurosci. 16, 899–908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kimberly W. T., Zheng J. B., Town T., Flavell R. A., Selkoe D. J. (2005) J. Neurosci. 25, 5533–5543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hoey S. E., Williams R. J., Perkinton M. S. (2009) J. Neurosci. 29, 4442–4460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhou Y. H., Chen Z., Purcell R. H., Emerson S. U. (2007) Immunol. Cell Biol. 85, 73–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Thornton J. M., Edwards M. S., Taylor W. R., Barlow D. J. (1986) EMBO J. 5, 409–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hussain I., Hawkins J., Shikotra A., Riddell D. R., Faller A., Dingwall C. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 36264–36268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chang W. P., Downs D., Huang X. P., Da H., Fung K. M., Tang J. (2007) FASEB J. 21, 3184–3196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rajendran L., Schneider A., Schlechtingen G., Weidlich S., Ries J., Braxmeier T., Schwille P., Schulz J. B., Schroeder C., Simons M., Jennings G., Knölker H. J., Simons K. (2008) Science 320, 520–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kouzarides T. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 1176–1179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Benjannet S., Elagoz A., Wickham L., Mamarbachi M., Munzer J. S., Basak A., Lazure C., Cromlish J. A., Sisodia S., Checler F., Chrétien M., Seidah N. G. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 10879–10887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fukumoto H., Takahashi H., Tarui N., Matsui J., Tomita T., Hirode M., Sagayama M., Maeda R., Kawamoto M., Hirai K., Terauchi J., Sakura Y., Kakihana M., Kato K., Iwatsubo T., Miyamoto M. (2010) J. Neurosci. 30, 11157–11166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. DeMattos R. B., Bales K. R., Cummins D. J., Dodart J. C., Paul S. M., Holtzman D. M. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 8850–8855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Mohajeri M. H., Gaugler M. N., Martinez J., Tracy J., Li H., Crameri A., Kuehnle K., Wollmer M. A., Nitsch R. M. (2004) Neurodegener Dis. 1, 160–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Patel M. M., Goyal B. R., Bhadada S. V., Bhatt J. S., Amin A. F. (2009) CNS Drugs 23, 35–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Alam M. I., Beg S., Samad A., Baboota S., Kohli K., Ali J., Ahuja A., Akbar M. (2010) Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 40, 385–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.