Abstract

Behavioral inhibition (BI) has been associated with the development of internalizing disorders in children and adolescents. It has further been shown that attentional control (AC) is negatively associated with internalizing problems. The combination of high BI and low AC may particularly lead to elevated symptomatology of internalizing behavior. This study broadens existing knowledge by investigating the additive and interacting effects of BI and AC on the various DSM-IV based internalizing dimensions. A sample of non-clinical adolescents (N = 1806, age M = 13.6 years), completed the Behavioral Inhibition System/Behavioral Activation System Scales (BIS/BAS), the attentional control subscale of the Adult Temperament Questionnaire (ATQ) and the Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS). As expected, BI was positively, and AC was negatively related to internalizing dimensions, with stronger associations of BI than of AC with anxiety symptoms, and a stronger association of AC than of BI with depressive symptoms. AC moderated the association between BI and all measured internalizing dimensions (i.e., symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, separation anxiety disorder, panic disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, and major depressive disorder). Since high AC may reduce the impact of high BI on the generation of internalizing symptoms, an intervention focused on changing AC may have potential for prevention and treatment of internalizing disorders.

Keywords: Adolescents, Anxiety, Depression, Attentional control, Behavioral inhibition

Introduction

The temperamental factors behavioral inhibition (BI)1 and attentional control (AC) have often been associated with the development of internalizing behaviors in youth as well as in adults (e.g. Johnson et al. 2003; Jorm et al. 1999; Muris et al. 2005). BI can be seen as reactive temperament and represents a proneness towards anxiety and a sensitivity towards signals of punishment and non-reward (Carver and White 1994). From a developmental point of view one could argue that BI causes the child to avoid stressful situations, which in turn could enhance the anxious symptoms. AC can be seen as regulative temperament, and represents the ability to focus and switch attention, and is a specific component of the overarching temperament trait of effortful control (Rothbart et al. 2004). Reactive temperament involves individual differences in emotional arousability, whereas regulative temperament modulates this reactivity. Eisenberg et al. (2000) have proposed that attentional control may especially be important in reducing internalizing symptoms, such as anxiety and sadness in children. As such, AC may be a moderator or buffering factor in the association between BI and internalizing disorders. High levels of AC would thus prevent those high on BI to develop anxiety disorders and depression disorders (Muris and Ollendick 2005; Nigg 2006).

In support of the view that high BI sets people at risk for developing internalizing psychopathology, previous work found positive relationships between BI and symptoms of DSM-IV based anxiety disorders and depression. Cross-sectional studies showed a firm relation between BI and anxiety in children (Muris et al. 2005) and between BI and depression in children (Nigg 2006). In prospective research Johnson et al. (2003) showed that BI was associated with anxiety disorders and depression in young adults. Some research has been done into the relevance of AC for the various internalizing disorders. There is empirical evidence that low AC is linked to self-reported anxiety symptoms in children between age 5–8 (Eisenberg et al. 2001), children aged 9–13 (Muris et al. 2004; Muris et al. 2006), adolescents aged 12–15 (Muris 2006), and adolescents aged 12–18 year (Vervoort et al. in press). In addition, it has been shown that effortful control is associated with symptoms of depression in children aged 9–13 (Muris et al. 2006) and adolescents aged 11–17 (Verstraeten et al. 2009). Prospectively, averaged deficits in attentional control predicted which individuals still had high scores on internalizing problems or even deteriorated over time at time 2 compared to time 1 (Eisenberg et al. 2009). With regard to the proposed moderating role of AC in the association between BI and internalizing disorders, three previous studies focusing on negative emotionality (similar to behavioral inhibition) have shown that the combination of high negative emotionality and low effortful control was associated with the highest levels of internalizing symptoms (Muris 2006; Muris et al. 2007; Oldehinkel et al. 2007).

Thus far research on BI, AC, and their interaction has focused on specific disorders (e.g. social phobia), or on internalizing behavior in general. It remains therefore to be examined whether low AC, and/or high BI can be best considered as more general characteristics of people suffering from symptoms of anxiety and/or mood disorders, or that the importance of low AC and/or high BI varies across the various internalizing disorders. The same holds for the proposed synergistic influence of AC and BI on the development of anxiety and mood symptomatology.

From a theoretical point of view we have no a priori reason to believe that BI and AC are more relevant to some anxiety disorders than others (see also: Nigg 2006). The various etiological models of specific DSM-IV anxiety disorders include both the presence of BI as a proneness towards perceived threat as well as the absence of AC as an impairment in the ability to regulate this proneness towards perceived threat. In these models the tendency to perceive threat involves negative social evaluations as in social phobia (Clark and Wells 1995), loss of control as in panic disorder (Clark 1986), future disaster as in generalized anxiety disorder (Wells 2005), and so forth, while low AC constitutes the inability to disengage attentional focus from such threat stimuli (Clark and Wells 1995; Wells 2005). While we thus regard BI as relevant for all anxiety disorder, depressed individuals are not primarily pre-occupied with threat, rather, they have a negative focus on self, the future, and the world (Beck et al. 1979). Such a negative focus is dissimilar to BI as defined as a proneness towards anxiety and a sensitivity towards signals of punishment and non-reward (Carver and White 1994). However, AC does have a role in the model by Beck et al. (1979), in which depressed people are unable to switch their attention away from their negative thoughts. Note that non of the existing theoretical models of anxiety and depression are explicit as to a mutually enhancing effect of high BI and low AC or, alternatively, on a buffering role of AC on the relation between BI and anxiety and depression. The above leads to the hypothesis that both BI and AC will play an important role in all anxiety disorders. In depression, however, we hypothesize a smaller role for BI than in anxiety disorders and a similar role for AC compared to anxiety disorders. Intuitively, the proposed synergistic effect is plausible for all anxiety disorders as well as for depression, and this will be explored.

In sum, the present study seeks to expand our insights into the role of low AC combined with high BI in symptoms of the various DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders. In addition to considering main effects we will test the hypothesis that AC may exert its protective effect mostly among those who are highly behaviorally inhibited (i.e., as a moderator). We extend previous work by studying the full range of anxiety and mood symptomatology, and expect a substantial role for BI and AC in all symptomatology related to the main anxiety disorders, and a more substantial role for AC than for BI in depressive symptomatology.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

As part of large scale anxiety prevention study (www.projectpasta.nl) a total number of 5,318 adolescents in the first and second year of regular secondary schools in the northern part of the Netherlands were invited to participate in a screening with the main goal of detecting adolescents with ‘at risk’ levels of anxiety. The invitation was sent out to adolescents and their parents via the attended school. Both parents and adolescents had to sign an informed consent. Of the 5,318, 1,806 adolescents and their parents (34%) gave their active informed consent for participation in the current study (813 boys and 993 girls, mean age 13.6 yrs, SD = .66). Of the participants, 68% came from a rural area and 32% from an urban area, as defined by Statistics Netherlands (http://www.rivm.nl/vtv/object_map/o2617n21780.html) and following Reijneveld et al. (2010). Furthermore, 97.1% of the participants had the Dutch nationality, with at least one Dutch parent, 2,9% of the participants were non-Dutch with at least one non-Dutch parent, 85,6% of the participants was living with their non-divorced biological parents. The assessment took place at school in groups of 15 participants at maximum. All questionnaires were completed on a laptop computer in the presence of a research assistant. At item level there are no missing data since the assessment took place on computers. The current study was approved by the medical ethical committee of the University Medical Center Groningen.

Questionnaires

Symptoms of DSM-IV Based Anxiety and Depression

The Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS; Chorpita et al. 2000) is a revised version of the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (SCAS; Spence 1998). It is a 47-item self-report, with items rated on a 4-point scale. The questionnaire consists of six scales: separation anxiety disorder (SAD), social phobia (SP), obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), panic disorder (PD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) and major depressive disorder (MDD). There is an overall scale indicating the total level of internalizing psychopathology. In psychometric research the internal consistency of the scale and subscales were found to be good in a normal as well as a clinical population (Chorpita et al. 2005; Chorpita et al. 2000). The structure of the RCADS was found to be consistent with DSM-IV anxiety disorders and depression. In the current study the following Cronbach’s alpha’s were found: total (α = .95), GAD (α = .84), SP (α = .86), SAD (α = .71), PD (α = .80), OCD (α = .72), and MDD (α = .80). These alpha’s were slightly higher compared to those reported in the Chorpita et al. study (2000).

Behavioral Inhibition

The Behavioral Inhibition/Behavioral Activation System Scales (BIS/BAS) (Carver and White 1994) is a 20-item self-report measure, with items rated on a 4-point scale. The BIS-scale measures reactions to the anticipation of punishment. The BAS-scale measures the tendency to approach behavior and positive affect. The psychometric properties of this questionnaire showed sufficient internal consistency for all subscales (Carver and White 1994). It was also shown that early adolescents’ data on the BIS/BAS were comparable to those obtained from adults (Cooper et al. 2007), making the instrument useful for adolescents. We used the BIS-scale in current study, which showed a satisfactory internal consistency (α = .73).

Attentional Control

The Adult Temperament Questionnaire (ATQ) (Rothbart et al. 2000) is a 77-item questionnaire, with items rated on a 7-point scale, measuring temperament. The instrument is an adaptation from the Physiological Reactions Questionnaire (Derryberry and Rothbart 1988) and is developed by Evans and Rothbart (2007). The ATQ contains four overarching scales; negative affect, extraversion, effortful control, and orienting sensitivity, each in turn consisting of subscales. For the purpose of the current study, the subscale Attentional Control of the scale Effortful Control was used, which measures the ability to focus and switch attention. The internal consistency of the ATQ is found to be good (for more information see: http://www.bowdoin.edu/%7Esputnam/rothbart-temperament-questionnaires/instrument-descriptions/adult-temperament-questionnaire.html). In the current study the subscale Attentional Control had satisfactory internal consistency (α = .71).

Statistical Analyses

We used hierarchical regression analyses to relate BI, AC, and their interaction to anxiety and depression. This was done separately for the following outcome variables: total anxiety symptoms (RCADS-TO), generalized anxiety disorder (RCADS-GA), social phobia (RCADS-SP), separation anxiety disorder (RCADS-SA), panic disorder (RCADS-PD), obsessive–compulsive disorder (RCADS-OC) and major depressive disorder (RCADS-DD). Since anxiety and depression tend to be more common in girls than in boys, we included gender as a main effect. In Step 1, the predictor variables gender, BI and AC were included in the regression equation using forced entry, and in Step 2 the interaction between BI and AC (BI × AC) was added. BI and AC were centered following the recommendations by Aiken and West (1991). With regard to gender, none of the interactions with any of the variables were significant or strong enough (i.e. of at least a small effect size of η2 = .01). Therefore, we decided to exclude gender-interactions from further regression analyses (in line with the recommended procedure described by Aiken and West 1991). Due to restriction of range and no significant correlations between age and other variables, age was not included in our final analyses.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Means, standard deviations, correlations and gender differences for all measures can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Correlations, Means and SD for internalizing dimensions, and gender differences on each variable (N = 1,806)

| TOT | GA | SP | SA | PD | OC | DD | BI | AC | Mean | SD | Gender differences | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | ||||||||||||

| Total | – | 25.95 | 16.42 | 154.42 | <.001 | ||||||||

| Generalized anxiety | .84* | – | 4.12 | 2.98 | 124.18 | <.001 | |||||||

| Social phobia | .88* | .68* | – | 8.07 | 4.79 | 145.37 | <.001 | ||||||

| Separation anxiety | .77* | .63* | .65* | – | 2.18 | 2.36 | 203.40 | <.001 | |||||

| Panic disorder | .84* | .64* | .66* | .58* | – | 3.45 | 3.35 | 90.99 | <.001 | ||||

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | .78* | .61* | .59* | .53* | .62* | – | 2.70 | 2.57 | 19.31 | <.001 | |||

| Depressive disorder | .83* | .61* | .64* | .54* | .66* | .59* | – | 5.44 | 3.73 | 86.68 | <.001 | ||

| Behavioral inhibition | .66* | .55* | .71* | .55* | .51* | .48* | .46* | – | 18.08 | 3.51 | 104.14 | <.001 | |

| Attentional control | −.54* | −.40* | −.47* | −.38* | −.44* | −.42* | −.52* | −.47* | 20.40 | 5.81 | 5.81 | .016 | |

| Age | −.02 | −.02 | −.01 | −.04 | .01 | −.03 | −.01 | −.02 | −.01 | 13.58 | 0.66 | 1.56 | .22 |

* p < .001. All gender differences, df (1,1804)

Gender differences were found on all the measures, with girls showing higher levels of anxiety and depression, and more BI and slightly lower levels of AC than boys.

Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression Related to Behavioral Inhibition and Attentional Control

For all dimensions of anxiety and mood problems, inclusion of BI × AC in Step 2 of the regression analysis led to a significant R2-change. Thus we report findings for the moderator model. Table 2 shows the outcomes for all dimensions.

Table 2.

Results of Hierarchical regression analysis for variables predicting DSM-IV based internalizing dimensions (N = 1,806)

| Dependent | Predictor | R2 change | B | SE | ß | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1 | Gender | .522** | 4.90 | .54 | .15 |

| BI | 2.27 | .09 | .48 | |||

| AC | −.90 | .05 | −.32 | |||

| 2 | BI × AC | .018** | −3.33 | .39 | −.14 | |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 1 | Gender | .325** | .88 | .12 | .15 |

| BI | .34 | .02 | .40 | |||

| AC | −.11 | .01 | −.21 | |||

| 2 | BI × AC | .012** | −.50 | .09 | −.11 | |

| Social phobia | 1 | Gender | .544** | 1.17 | .16 | .12 |

| BI | .81 | .03 | .59 | |||

| AC | −.17 | .02 | −.21 | |||

| 2 | BI × AC | .014** | −.87 | .11 | −.12 | |

| Separation anxiety disorder | 1 | Gender | .360** | .99 | .09 | .21 |

| BI | .28 | .02 | .42 | |||

| AC | −.08 | .01 | −.19 | |||

| 2 | BI × AC | .016** | −.44 | .07 | −.13 | |

| Panic disorder | 1 | Gender | .325** | .79 | .13 | .12 |

| BI | .35 | .02 | .36 | |||

| AC | −.16 | .01 | −.28 | |||

| 2 | BI × AC | .018** | −.67 | .10 | −.14 | |

| Obsessive–compulsive disorder | 1 | Gender | .256** | .06 | .11 | .01n.s. |

| BI | .23 | .02 | .32 | |||

| AC | −.12 | .01 | −.28 | |||

| 2 | BI × AC | .007** | −.31 | .08 | −.082 | |

| Major depressive disorder | 1 | Gender | .343** | 1.00 | .15 | .13 |

| BI | .26 | .02 | .24 | |||

| AC | −.26 | .01 | −.41 | |||

| 2 | BI × AC | .009** | −.53 | .11 | −.10 | |

** p < .001. All shown variables were significant at .000, except for gender on obsessive–compulsive disorder. Results of separate regression analyses for boys and girls can be obtained from the authors, they are not displayed since gender had no additive effect in products with other variables

Gender was a significant predictor for symptoms of depression and all types of anxiety disorders except obsessive–compulsive disorder. Girls showed higher levels of anxiety and depression compared to boys. In all analyses, BI, AC and BI × AC showed significant results. Betas indicate that higher levels of BI and lower levels of AC lead to higher levels of symptoms of anxiety and depression. On top of that, the interaction between BI × AC was also significantly related to all dimensions of anxiety and depression. Looking at possible differences between the various DSM-IV internalizing dimensions, it can be seen in Table 2 that for all anxiety problem dimensions, BI was the strongest predictor, AC the second strongest predictor, and BI × AC the weakest but significant predictor. For depressive problems this picture was different: AC was the strongest predictor, with BI coming in second place, and BI × AC coming last. For AC, the differences in regression weights between depressive symptoms and the anxiety dimensions is significant, with non-overlapping confidence intervals of B for symptoms of depression ranging from −.28 up to −.24 around point estimate B = −.26, and symptoms of social phobia (being the nearest anxiety interval) ranging from −.21 up to −.13 around point estimate B = −.17. No differences in regression weights for AC were found between the various DSM-IV based anxiety dimensions. For BI the regression weight of symptoms of social phobia differed significantly from all other DSM-IV based anxiety dimensions as well as from symptoms of depression (social phobia: .75 up to .87 around point estimate B = .81 compared to nearest interval for panic disorder: .31 up to .39 around point estimate B = .35). A closer look into the strength of the association of BI within the various anxiety dimensions showed that the differences were small and that all regression weights had an overlap with at least two other anxiety dimensions. These differences were therefore considered as less relevant. No differences were found between regression weights for the interaction term BI × AC in the various DSM-IV-based internalizing symptomatologies.

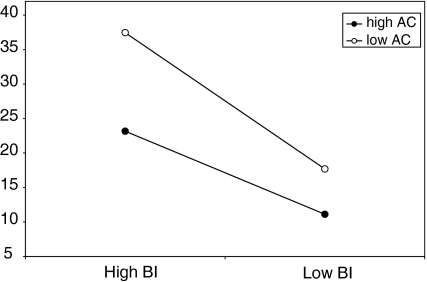

Figure 1 displays the interaction effect for internalizing complaints in general. As can be seen in Fig. 1, if participants have high scores on BI their score on internalizing symptoms is higher, this is also the case in reverse for AC, were low AC is related to higher scores on internalizing symptoms. The highest scores are found for participants with high BI in combination with low AC, this interaction effect is significant.

Fig. 1.

Interaction effects of behavioral inhibition and attentional control for DSM-IV based internalizing complaints (RCADS total subscale)

Discussion

The present study examined the independent and joint associations of BI, AC, and their interaction with DSM-IV based internalizing problems. Results of the current study can be summarized as follows: (i) BI was positively and AC was negatively related to the severity of symptoms of all DSM-IV based internalizing disorders; (ii) The BI × AC interaction effect consistently showed cumulative predictive validity where high AC reduced the effect of BI on all DSM-IV based internalizing problem dimensions; (iii) In symptoms of depression, AC played a larger role than in the DSM-IV based anxiety dimensions. Symptoms of depression were most strongly related to AC, while symptoms of social phobia, separation anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder were most strongly related to BI.

Replicating previous research (e.g., Muris et al. 2005; Johnson et al. 2003), the present results showed a robust relationship between high BI and DSM-IV based internalizing disorders. Next to that our results broaden current knowledge by showing this relation for different DSM-IV based anxiety disorders. Importantly, a negative and robust association was also found for low AC, as was shown before by Eisenberg et al. (2001). Although BI systematically showed the strongest relationship with symptoms of anxiety, AC was also found to have substantial additional explanatory power to symptoms of DSM-IV anxiety disorders. Thus the present results indicate that low AC is an important additional characteristic of all DSM-IV based anxiety domains. Comparing the various DSM-IV based disorders, it appears that for symptoms of social phobia BI is significantly more influential than in the other measured dimensions. This difference however may be due to the fact that the items in the BIS subscale partly focus on a sensitivity for social evaluation, hence, to the specific operationalization of BI in the present study (Carver and White 1994) rather than reflecting a stronger association with social phobia per se. These findings would hold only if the results were replicated using different models such as the Kagan model of BI (Kagan et al. 1988) or the broader construct of negative affectivity from the temperament model of Rothbart et al. (2000). For all other DSM-IV based anxiety disorders, the strength of the association with BI was highly similar. For symptoms of depression, we found that AC plays a larger role than for the DSM-IV based anxiety dimensions which was according to expectations. Also as expected, no differences emerged across the various anxiety dimensions with respect to AC.

Perhaps most important, BI × AC independently contributed to the model. This again was a robust finding in all measured anxiety and depression dimensions. These results are consistent with previous research that focused on the role of effortful control in internalizing problems in general (Oldehinkel et al. 2007), in depression (Verstraeten et al. 2009; Muris 2006), and in anxiety (Muris et al. 2004). These findings extend previous findings by showing that this buffering effect holds for symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, separation anxiety disorder, panic disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, and major depressive disorder. The results are consistent with the view that high AC may function as a buffer between BI and the development of DSM-IV based internalizing complaints (Muris and Ollendick 2005), while individuals with high BI combined with low AC report the highest levels of DSM-IV based internalizing symptoms. If prospective studies would show that high BI and low AC precede DSM-IV based internalizing symptoms, this might be of importance for identifying adolescents at high risk of developing an anxiety or mood disorder. It should be noted however that the interaction had small additive value on top of BI and AC, with BI and AC each having the largest associations, thus the identification of potentially at risk adolescents should focus primarily on high BI or low AC.

Our results are not only of theoretical interest but also provide clues for clinical interventions. More specifically, our findings support the view that training AC might be a helpful strategy in the prevention and/or treatment of internalizing disorders. In support of this, there is already some preliminary evidence for the useful application of cognitive control training in depressed adults (Siegle et al. 2007) and of task concentration training in social phobia (Mulkens et al. 2001). It would be interesting to see whether also in children and/or adolescents AC training would help to reduce symptoms of internalizing disorders. In a similar vein it would be interesting to examine whether AC training may also be helpful in the prevention of the onset or recurrence of internalizing disorders in adolescence.

One possible limitation is that AC was assessed by a self-report measure. It can not be ruled out that subjective AC does not (completely) match with actual capacity of self-regulation by AC (Reinholdt-Dunne et al. 2009). It would therefore be important for future research to test whether similar results would emerge when using a behavioral measure of executive functioning (EF) such as the Attentional Network Task (Reinholdt-Dunne et al. 2009; ANT; Fan et al. 2002). Some promising research in this field has been done by Derakshan et al. (2009), who showed that in undergraduate students anxiety is related to attentional control as measured by task-switching tasks. Adding a parent or teacher report of AC may be another helpful strategy to differentiate between individuals’ perception of their AC and their actual capacity to regulate their attention. This differentiation is also of importance for training applications, with training either focused on direct training AC through a specific attentional control training or focused on changing the perceptions of AC, for instance through cognitive therapy, or both.

Second, the present sample may have been prone to selection bias, since invited adolescents were all informed beforehand on the nature of our research. That is, the current data were collected as part of a large screening with the ultimate aim to select groups of adolescents to be included in training for the prevention of anxiety. When comparing the means on the self-report questionnaire (RCADS) with same aged adolescents measured in the context of a large longitudinal cohort study in the Netherlands (Van Oort et al. 2009), the adolescents in our sample have higher scores on all DSM-IV based internalizing dimensions. However, there seems to be no obvious reason to assume that the present correlational findings would be different in a less anxious sample.

Third, one could argue that in particular the cross-sectional study of the association between BI and anxiety is somewhat tautological. While the BIS scale measures the predisposition to anxiety, the DSM-IV scales measure the actual experience, i.e., the state, of anxiety (see Jorm et al. 1999). We acknowledge that these measurements are likely to be confounded by one another. Nonetheless, the association between BI and anxiety and mood disorders has already been established prospectively, as well as by means of different methods and operationalizations of the BI construct (Kagan et al. 1988; Biederman et al. 1993). The additional value of the current paper lies in the fact that we showed that AC had additional value above and beyond BI for all DSM-IV based anxiety and mood problems, by itself and in interaction with BI.

Finally, it should be acknowledged that the cross-sectional design of our study does not allow any firm conclusion regarding the direction of found associations. To arrive at more solid grounds in this respect it would be important to test presently found associations in a longitudinal design and to determine prospectively whether the combination of AC and BI and their interaction have prognostic value for the onset of mood and/or anxiety disorders.

To conclude, both high BI and low AC were found to have independent and mutually enhancing associations with all anxiety and depression dimensions that were derived from the DSM-IV. Since AC may buffer the relationship between BI and internalizing problems as well as protect for internalizing problems by itself, the training of attentional control strategies may be a promising route for modifying or preventing symptoms of anxiety and depression in adolescents.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a ZonMw grant (the Netherlands organization for health research and development), nr. 62200027.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Footnotes

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Rosenbaum JF, Bolduc-Murphy EA, Faraone SV, Chaloff J, Hirshfeld DR, et al. A 3-year follow-up of children with and without behavioral inhibition. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32:814–821. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199307000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver SC, White TL. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:319–333. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.2.319. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Moffitt CE, Gray J. Psychometric properties of the revised child anxiety and depression scale in a clinical sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43:309–322. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Yim L, Moffitt CE, Umemoto LA, Francis SE. Assessment of symptoms of DSM-IV anxiety and depression in children: A revised child anxiety and depression scale. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2000;38:835–855. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM. A cognitive approach to panic. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1986;24:461–470. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(86)90011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM, Wells A. A cognitive model of social phobia. In: Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, Hope DA, Schneier FR, editors. Social phobia. New York: The Guilford Press; 1995. pp. 69–93. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper A, Gomez R, Aucote H. The behavioural inhibition system and behavioural approach system (BIS/BAS) scales: Measurement and structural invariance across adults and adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43:295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.11.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Derakshan N, Smyth SA, Eysenck MW. Effects of state anxiety on performance using a task-switching paradigm: An investigation of attentional control theory. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2009;16:1112–1117. doi: 10.3758/PBR.16.6.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derryberry D, Rothbart MK. Arousal, affect, and attentio as components of temperament. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;55:958–966. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.55.6.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Reiser M, et al. The relations of regulation and emotionality to children’s externalizing and internalizing problem behaviour. Child Development. 2001;72:1112–1134. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Guthrie IK, Reiser M. Dispositional emotionality and regulation: Their role in predicting quality of social functioning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:136–157. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.78.1.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Valiente C, Spinrad TL, Cumberland A, Liew J, Reiser M, et al. Longitudinal relations of children’s effortful control, impulsivity, and negative emotionality to their externalizing, internalizing, and co-occurring behavior problems. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:988–1008. doi: 10.1037/a0016213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DE, Rothbart MK. Developing a model for adult temperament. Journal of Research in Personality. 2007;41:868–888. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2006.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J, McCandliss B, Sommer T, Raz A, Posner MI. Testing the efficiency and independence of attentional networks. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2002;14:340–347. doi: 10.1162/089892902317361886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. Causal theories of personality and how to test them. In: Royce JR, editor. Multivariate analysis and psychological theory. London; New York: Academic Press; 1973. pp. 409–463. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Turner RJ, Iwata I. BIS/BAS levels and psychiatric disorder: An epidemiological study. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2003;25:25–36. doi: 10.1023/A:1022247919288. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF, Christensen H, Henderson AS, Jacomb PA, Korten AE, Rodgers B. Using the BIS/BAS scales to measure behavioural inhibition and behavioural activation: Factor structure, validity, and norms in a large community sample. Personality and Individual Differences. 1999;26:49–58. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00143-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Reznick JS, Snidman N. Biological bases of childhood shyness. Science. 1988;240:167–171. doi: 10.1126/science.3353713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulkens S, Bögels SM, de Jong PJ, Louwers J. Fear of blushing: Effects of task concentration training versus exposure in vivo on fear and physiology. Anxiety Disorders. 2001;15:413–432. doi: 10.1016/S0887-6185(01)00073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P. Unique and interactive effects of neuroticism and effortful control on psychopathological symptoms in non-clinical adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences. 2006;40:1409–1419. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, de Jong PJ, Engelen S. Relationships between neuroticism, attentional control, and anxiety disorders symptoms in non-clinical children. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;37:789–797. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2003.10.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Meesters C, Blijlevens P. Self-reported reactive and regulative temperament in early adolescence: relations to internalizing and externalizing problem behavior and “Big Three” personality factors. Journal of Adolescence. 2007;30:1035–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Meesters C, de Kanter E, Timmerman PE. Behavioural inhibition and behavioural activation system scales for children: relationships with Eysenck’s personality traits and psychopathological symptoms. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;38:831–841. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2004.06.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Meesters C, Rompelberg L. Attentional control in middle childhood: Relations to psychopathological symptoms and threat perception distortions. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;45:997–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Ollendick TH. The role of temperament in the etiology of child psychopathology. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2005;8:271–289. doi: 10.1007/s10567-005-8809-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT. Temperament and developmental psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:395–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldehinkel AJ, Hartman CA, Ferdinand RF, Verhulst FC, Ormel J. Effortful control as modifier of the association between negative emotionality and adolescents’ mental health problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:523–539. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reijneveld SA, Veenstra R, de Winter AF, Verhulst FC, Ormel J, de Meer G. Area deprivation affects behavioral problems of young adolescents in mixed urban and rural areas: The TRAILS study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46:189–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinholdt-Dunne ML, Mogg K, Bradley BP. Effects of anxiety and attention control on processing pictorial and linguistic emotional information. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47:410–417. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Evans DE. Temperament and personality: Origins and outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:122–135. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.78.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ellis LK, Posner MI. Temperament and self-regulation. In: Baumeister RF, Vohs KD, editors. Handbook of self-regulation. Research, theory, and applications. New York: Guilford Press; 2004. pp. 357–370. [Google Scholar]

- Siegle GJ, Ghinassi F, Thase ME. Neurobehavioral therapies in the 21st century: Summary of an emerging field and extended example of cognitive control training for depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2007;31:235–262. doi: 10.1007/s10608-006-9118-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spence SH. A measure of anxiety symptoms in children. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1998;36:545–566. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Oort FVA, Greaves-Lord K, Verhulst FC, Ormel J, Huizink AC. The developmental course of anxiety symptoms during adolescence: The TRAILS study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:1209–1217. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstraeten K, Vasey MW, Raes F, Bijttebier P. Temperament and risk for depressive symptoms in adolescence: Mediation by rumination and moderation by effortful control. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:349–361. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9293-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vervoort, L., Wolters, L. H., Hoogendoorn, S. M., Prins, P. J., de Haan, E., Boer, F. et al. (in press). Temperament, attentional processes and anxiety: diverging links between clinically anxious and non-clinical adolescents? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wells A. The metacognitive model of GAD: Assessment of meta-worry and relationship with DSM-IV generalized aniety disorder. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2005;29:107–121. doi: 10.1007/s10608-005-1652-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]