Abstract

Mucopolysaccharidosis VII (MPS VII; Sly syndrome) is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by a deficiency of β-glucuronidase (GUS, EC 3.2.1.31; GUSB). GUS is required to degrade glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), including heparan sulfate (HS), dermatan sulfate (DS), and chondroitin-4,6-sulfate (CS). Accumulation of undegraded GAGs in lysosomes of affected tissues leads to mental retardation, short stature, hepatosplenomegaly, bone dysplasia, and hydrops fetalis. We summarize information on the 49 unique, disease-causing mutations determined so far in the GUS gene, including nine novel mutations (eight missense and one splice-site). This heterogeneity in GUS gene mutations contributes to the extensive clinical variability among patients with MPS VII. One pseudodeficiency allele, one polymorphism causing an amino acid change, and one silent variant in the coding region are also described. Among the 103 analyzed mutant alleles, missense mutations accounted for 78.6%; nonsense mutations, 12.6%; deletions, 5.8%; and splice-site mutations, 2.9%. Transitional mutations at CpG dinucleotides made up 40.8% of all the described mutations. The five most frequent mutations (accounting for 44/103 alleles) were exonic point mutations, p.L176F, p.R357X, p.P408S, p.P415L, and p.A619 V. Genotype/phenotype correlation was attempted by correlating the effects of certain missense mutations or enzyme activity and stability within phenotypes. These were in turn correlated with the location of the mutation in the tertiary structure of GUS. A total of seven murine, one feline, and one canine model of MPS VII have been characterized for phenotype and genotype.

Keywords: GUS, GUSB, mucopolysaccharidosis VII, MPS VII, Sly syndrome, alignment

Introduction

Mucopolysaccharidosis VII (Sly Syndrome; MPS VII) is an autosomal recessive disease classified in the group of mucopoly-saccharide storage diseases. MPS VII (MIM 253220) is characterized by the deficiency of activity of the enzyme β-glucuronidase (GUS: β-D-glucuronoside glucuronosohydrolase, EC 3.2.1.31; GUSB; MIM 611499) [Sly et al., 1973]. It is one of a class of diseases due to a deficiency of one of the dozen enzymes involved in the stepwise degradation of glycosaminoglycans (GAGs). In the absence of GUS, chondroitin sulfate (CS), dermatan sulfate (DS), and heparan sulfate (HS) are only partially degraded and accumulate in the lysosomes of many tissues, eventually leading to cellular and organ dysfunction. MPS VII is a rare disorder, and precise epidemiologic data are scarce. MPS VII causes mental retardation, hepatosplenomegaly, and skeletal dysplasia. MPS VII patients displayed a wide range of clinical variability, from the most severe type with hydrops fetalis to a milder phenotype with later onset and normal intelligence. MPS VII patients with the most severe phenotype have hydrops fetalis at birth and often do not survive beyond a few months. Patients with mild manifestations of MPS VII have survived into the fifth decade of life. MPS VII has also been reported in canine, feline, and murine species [Haskins et al., 1984; Birkenmeier et al., 1989; Sands and Birkenmeier, 1993; Gitzelmann et al., 1994; Gwynn et al., 1998; Ray et al., 1998; Fyfe et al., 1999; Sly et al., 2001; Vogler et al., 2001; Tomatsu et al., 2002b, 2003]. The initially described, natural MPS VII mice (gusmps/mps) have a 1-bp deletion in exon 10 and have similar morphologic, genetic, and biochemical characteristics to human MPS VII patients, showing degenerative disease with progressive disability, widespread organ dysfunction, facial dysmorphism, growth retardation, deafness, behavioral deficits, and shortened lifespan [Birkenmeier et al., 1989; Sands and Birkenmeier, 1993]. We produced mL175F (corresponding to p.L176F, the most common human mutation), mE536A, and mE536Q (active site nucleophile replacements, corresponding to p.E540A and p.E540Q in humans) knock-in mice [Tomatsu et al., 2002b]. These models reflect the various clinical phenotypes of human MPS VII (Sly syndrome). Advanced treatments such as enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) and gene therapy for MPS VII are currently being developed using these models. We have recently created MPS VII mouse models tolerant to infused human GUS enzyme to test various treatment protocols using the human gene product [Sly et al., 2001; Tomatsu et al., 2003].

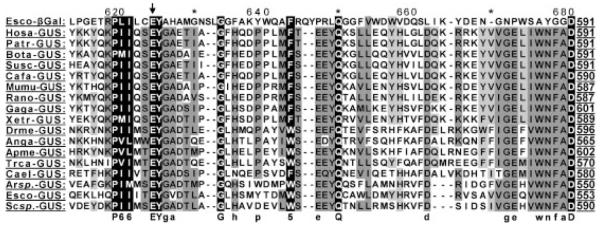

Characterization of GUS protein by X-ray crystallography and homology comparisons among several species of GUS and bacterial β-galactosidases suggested R382, E451, and E540 asactive site residues [Jain et al., 1996; Islam et al., 1999]. These three residues of human GUS are conserved among GUS and β-galactosidase proteins from bacterial species [Henrissat, 1991]. E540 was identified experimentally as the active site nucleophile of the human enzyme [Wong et al., 1998].

Isolation and characterization of the human cDNA and genomic gene made investigation of molecular lesions in the GUS gene of MPS VII patients feasible [Oshima et al., 1987; Miller et al., 1990; Shipley et al., 1991]. The GUS gene is located on chromosome arm 7 [Speleman et al., 1996] and spans approximately 20 kb containing 11 introns and 12 exons. The 1,953-bp GUS mRNA encodes a 651–amino acid precursor. After cleavage of a 22–amino acid N-terminal signal peptide and glycosylation, the 78-kDa monomer is transported to lysosomes and cleaved in the lysosome to become the 60-kDa and 18-kDa subunits of the mature active enzyme [Brot et al., 1978; Oshima et al., 1987].

MPS VII Mutations and their Biological Relevance

To date, 49 different mutations including nine novel mutations in the GUS gene have been found in MPS VII patients. These mutations have been identified in 103 mutant alleles in a total group of 56 patients by a variety of molecular techniques (92.0% of total investigated alleles) (Table 1). The numbers for the nucleotide changes are reported in accordance with GenBank entry NM_010368.1. Three nonpathogenic variants within the coding sequence of the GUS gene have been also identified (one pseudodeficiency, one benign amino acid change, one silent change) (Table 2). The DNA mutation numbering is based on cDNA sequence. For cDNA numbering, +1 corresponds to the A of the ATG translation initiation codon in the reference sequence. The MPS VII patients were defined as attenuated if they did not have hydrops fetalis and severe mental retardation leading to death within a year.

Table 1.

Mutations in the GUSB Gene Causing MPS VII*

| Nucleotide changea |

Effect on amino acid |

Exon | Degree of conservation of aab |

Phenotype defined |

Detected alleles (n) |

Populationc | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.f8C>T | p.P30S | 1 | 2 | Undefined | 1 | Un | Vervoort (unpublished results) |

| c.112T>G | p.C38G | 1 | 4 | Attenuated | 2 | It | Vervoort et al. [1998a] |

| c.155C>T | p.S52F | 1 | 2 | Severe | 1 | Cz | Vervoort et al. [1997] |

| c.328C>T | p.R110X | 2 | 3 | Severe | 1 | Be | Vervoort et al. [1997] |

| c.406G>A | p.G136R | 3 | 2 | Undefined | 2 | Bt | Vervoort et al. [1996] |

| c.442C>T | p.P148S | 3 | 1 | Severe | 1 | Cc | Yamada et al. [1995] |

| c.448G>A | p.E150K | 3 | 1 | Severe | 1 | Ch | Vervoort et al. [1996] |

| c.455A>G | p.D152G | 3 | 3 | Attenuated | 1 | Un | Sly (unpublished results) |

| c.526C>T | p.L176F | 3 | 1 | Attenuated | 21 | Sp, Br, Mn, Mx |

Wu et al. [1994]; Vervoort et al. [1996]; Schwartz et al. [2003] |

| Am, Fr-Ca, Bt, Tu |

Sly (unpublished results); Young (unpublished results) |

||||||

| c.581+1G>A | p.K194fsX22 | Intron 3 |

Severe | 1 | Pk | Young (unpublished results) | |

| c.646C>T | p.R216W | 4 | 1 | Severe | 4 | Du, Be, Un | Vervoort et al. [1993, 1996, 1997] |

| c.728T>C | p.L243P | 5 | 2 | Severe | 1 | Bt, Tu | Young (unpublished results) |

| c.935C>G | p.S312X | 6 | 4 | Severe | 1 | Be | Vervoort et al. [1996] |

| c.959A>G | p.Y320C | 6 | 1 | Undefined | 1 | Ge | Vervoort et al. [1996] |

| c.959A>C | p.Y320S | 6 | 1 | Severe | 1 | Fi | Vervoort et al. [1996] |

| c.1016A>G | p.N339S | 6 | 1 | Undefined | 1 | Am | Sly (unpublished results) |

| c.1050G>C | p.K350N | 6 | 2 | Attenuated | 1 | Ge | Storch et al. [2003] |

| c.1051C>T | p.H351Y | 6 | 1 | Severe | 1 | Fi | Vervoort et al. [1996] |

| c.1061C>T | p.A354V | 6 | 4 | Severe | 1 | Cc | Wu and Sly [1993] |

| c.1069C>T | p.R357X | 7 | 2 | Severe | 7 | Be, Ch, Du, Am |

Shipley et al. [1993]; Vervoort et al. [1996, 1997]; Sly (unpublished results) |

| c.1081_1107del27 | p.F361- D369del |

7 | Severe | 2 | Du, Be | Vervoort et al. [1997] | |

| c.1084G>A | p.D362N | 7 | 1 | Severe | 2 | Mx | Sly (unpublished results) |

| c.1091C>T | p.P364L | 7 | 3 | Undefined | 1 | Am | Sly (unpublished results) |

| c.1120C>T | p.R374C | 7 | 2 | Undefined | 2 | Cz, Ge | Vervoort et al. [1996, 1997] |

| c.1144C>T | p.R382C | 7 | 1 | Undefined | 4 | Jp, Fr |

Fukuda et al. [1991]; Tomatsu et al. [1991]; Vervoort et al. [1996] |

| c.1145G>A | p.R382H | 7 | 1 | Attenuated | 1 | Fr | Vervoort et al. [1996] |

| c.1222C>T | p.P408S | 7 | 2 | Attenuated | 5 | Mx | Islam et al. [1996]; Islam et al. [1998]; Sly (unpublished results) |

| c.1244C>T | p.P415L | 7 | 4 | Attenuated | 5 | Mx | Islam et al. [1996, 1998]; Sly (unpublished results) |

| c.1244+1G>A | p.P415fsX1 | Intron 7 |

Severe | 2 | Mx | Vervoort et al. [1997] | |

| c.1304G>C | p.R435P | 8 | 2 | Severe | 2 | Tu | Vervoort et al. [1996] |

| c.1337G>A | p.W446X | 8 | 1 | Attenuated | 1 | Sw | Vervoort et al. [1998a] |

| c.1429C>T | p.R477W | 9 | 1 | Severe | 4 | Kw, Ma | Vervoort et al. [1996] |

| c.1454_1457del4 | p.S485fsX13 | 9 | Severe | 1 | Be | Vervoort et al. [1997] | |

| c.1484A>G | p.Y495C | 10 | 2 | Severe | 1 | Cc | Yamada et al. [1995] |

| c.1520G>A | p.W507X | 10 | 1 | Severe | 1 | Fr | Vervoort et al. [1996] |

| c.1521G>A | p.W507X | 10 | 1 | Severe | 2 | Cc, Am | Yamada et al. [1995]; Sly (unpublished results) |

| c.1523A>G | p.Y508C | 10 | 1 | Attenuated | 1 | Fr | Vervoort et al. [1996] |

| c.1616_1653del38 | p.S539RfsX7 | 10 | Severe | 1 | Cc | Yamada et al. [1995] | |

| c.1618G>A | p.E540K | 10 | 1 | Attenuated | 1 | Un | Sly (unpublished results) |

| c.1715G>A | p.G572D | 11 | 4 | Severe | 2 | In | Vervoort et al. [1996] |

| c.1730G>T | p.R577L | 11 | 2 | Attenuated | 2 | Ge, Mx | Storch et al. [2003]; Sly (unpublished results) |

| c.1775delT | p.F592SfsX2 | 11 | Undefined | 1 | Fr | Vervoort et al. [1998b] | |

| c.1818G>T | p.K606N | 12 | 2 | Attenuated | 2 | Al | Vervoort et al. [1996] |

| c.1820G>C | p.G607A | 12 | 1 | Severe | 1 | Un | Sly (unpublished results) |

| c.1831C>T | p.R611W | 12 | 1 | Severe | 1 | Cc | Wu and Sly [1993] |

| c.1856C>T | p.A619V | 12 | 1 | Attenuated | 5 | Jp | Tomatsu et al. [1990, 1991] |

| c.1874_1875delGA | p.R625IfsX6 | 12 | Severe | 1 | Be | Vervoort et al. [1996] | |

| c.1876T>C | p.Y626H | 12 | 1 | Attenuated | 1 | It | Vervoort et al. [1998a] |

| c.1881G>T | p.W627C | 12 | 3 | Attenuated | 2 | Am | Shipley et al. [1993]; Vervoort et al. [1996] |

The numbers for the nucleotide changes are reported in accordance with GenBank entry NM_010368.1, NP_034498.1.

The DNA mutation numbering is based on cDNA sequence. Nucleotides are numbered from the ATG initiation codon as suggested by den Dunnen and Antonarakis et al. [2001] and per HGVS guidelines (www.hgvs.org).

1, conserved among all species; 2, vertebrate specific; 3, mammal specific; 4, nonconserved.

Al, Algerian; Am, American; Be, Belgian; Br, Brazilian; Bt, British; Cc, Caucasian; Ch, Chilean; Cz, Czechoslovakian; Du, Dutch; Fi, Finnish; Fr, French; Fr-Ca, French-Canadian; Ge, German; In, Indian; It, Italian; Jp, Japanese; Kw, Kuwaiti; Ma, Maghrebi; Mn, Mennonite; Mx, Mexican; Pk, Pakistani; Sp, Spanish; Sw, Swiss; Tu, Turkish; Un, unknown.

aa, amino acid(s).

Table 2.

Nonpathogenic Variants of the GUSB Gene*

| Base changea | Codon change | Effect | Region | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.454G>A | GAC>AAC | p.D152N | Exon 3 | Vervoort et al. [1995]; Vervoort et al. [1998a] |

| c.1740T>C | TAT>TAC | Exon 11 | Vervoort et al. [1998a] | |

| c.1946C>T | CCG>CTG | p.P649L | Exon 12 |

Tomatsu et al. [1991]; Wu et al. [1994]; Vervoort et al. [1997]; Vervoort et al. [1998a] |

The numbers for the nucleotide changes are reported in accordance with GenBank entry NM_010368.1, NP_034498.1.

The DNA mutation numbering is based on cDNA sequence. Nucleotides numbered from the ATG initiator codons as suggested by den Dunnen and Antonarakis et al. [2001] and per HGVS guidelines (www.hgvs.org).

The mutations are distributed along the whole gene and all types of mutations except insertion and rearrangement were found. The total of 49 mutations includes 36 missense mutations, six nonsense, two splice site mutations, and five deletions. The number of each type of mutation in a total of 103 mutant alleles was 81 alleles for missense mutations (78.6%), 13 for nonsense (12.6%), six for deletions (5.8%), and three for splice-site mutations (2.9%). Thus, missense mutations are the most prevalent among GUS mutations. The five most frequent mutations (Table 1) are represented by single nucleotide changes. Together, they make up 36.9% of all described mutant alleles. The remaining 63.1% of mutations each occur less than four times in the mutant population, indicating extensive molecular heterogeneity in GUS mutations.

Relation Between Transitions at CpG Sites and the Methylation Status of CpG Sites in the GUSB Gene

The variety, frequency, and location of point mutations causing human genetic disease are highly nonrandom. One important factor contributing to the nonrandomness at the DNA level is the local DNA sequence environment, especially CpG dinucleotides. DNA methylation at the cytosine residue of CpG dinucleotides produces 5-methylcytosine, which results in a C-to-T transitional change following deamination. The importance of CpG methylation in the etiology of genetic diseases was deduced from the evidence that 10 to 60% of point mutations causing human diseases in different genes result from transitions at CpG dinucleotides [Krawczak et al., 1998; Antonarakis et al., 2001].

There are 17 transitional mutations at CpG sites in the GUS gene. Transitions at CpG dinucleotides account for 40.8% of described mutant alleles and 44.7% of exonic point mutations that cause MPS VII. This percentage is higher than that compiled from many genes described previously [Krawczak et al., 1998; Antonarakis et al., 2001] and represents around a 30-fold higher probability of a transitional mutation at a CpG dinucleotide than expected. These findings explain why many transitional mutations at CpG sites are recurrent. No transitional mutation at CpG sites has been detected in exon 1. To explain this discrepancy, we analyzed the methylation pattern of the GUS coding region by a sensitive bisulfite-based technique [Tomatsu et al., 2002a]. We found that methylation of the 67 individual CpG cytosines within exons 2 to 12 was extensive while 24 CpG cytosines in exon 1 were completely unmethylated. All of the 17 transitional mutations at CpG sites out of the 42 exonic point mutations were located between exons 2 and 12, demonstrating the correlation of nonmethylation of exon 1 with the absence of transitional mutations at CpG sites in exon 1 and the reverse for exons 2 to 12. One pseudodeficiency allele (p.D152N) and one benign polymorphism allele (p.P649L), both of which change an amino acid residue, are also derived from G-to-A or C-to-T transition at CpG dinucleotides, respectively [Tomatsu et al., 1991; Vervoort et al., 1995].

Missense Mutations

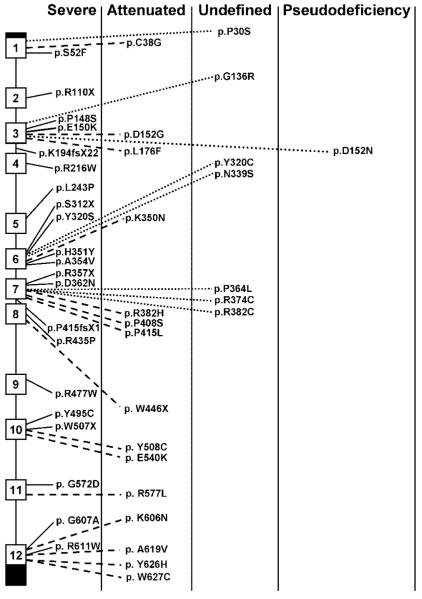

This is the most frequent group of GUS mutations, with 36 changes including eight novel amino acid substitutions reported here (Tables 1 and 3; Fig. 1). Correlation of individual mutation with disease severity is based on phenotype of the homozygotes, predicted change of tertiary structure of the protein, and the observed level of enzyme activity on in vitro expression.

Table 3.

Combination of Alleles Producing Attenuated Phenotypes*

| Base changea (first allele) | Amino acid changeb | Factors defined as attenuated | Base change (second allele) | Amino acid change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.112T>G | p.C38G | 3 | c.1876T>C | p.Y626H |

| c.455A>C | p.D152G | 4 | c.1618G>A | p.E540K |

| c.526C>T | p.L176F | 1,2,3 | c.526C>T | p.L176F |

| c.1050G>C | p.K350N | 3 | c.1730G>T | p.R577L |

| c.1061C>T | p.A354V | 3 | c.1831C>T | p.R611W |

| c.1144C>T | p.R382C | 1,3 | c.1144C>T | p.R382C |

| c.1145G>A | p.R382H | 2,3 | c.1523A>G | p.Y508C |

| c.1222C>T | p.P408S | 1,3 | c.1244C>T, c.1222C>T | p.P415L, p.P408S |

| c.1244C>T | p.P415L | 1,3 | c.1244C>T, c.1222C>T | p.P415L, p.P408S |

| IVS8+0.6kbdelTC | ? | 3 | p.13376G>A | p.P446X |

| c.1523A>G | p.Y508C | 3 | c.1145G>A | p.R382H |

| c.1730G>T | p.R577L | 3 | c.1050G>C | p.K350N |

| c.1856C>T | p.A619V | 1,3 | c.1856C>T | p.A619V |

| c.1876T>C | p.Y626H | 3 | c.112T>G | p.C38G |

| c.1881G>T | p.W627C | 3,4 | c.1069C>T | p.R357X |

The numbers for the nucleotide changes are reported in accordance with GenBank entry NM_010368.1, NP_034498.1.

The DNA mutation numbering is based on cDNA sequence. Nucleotides numbered from the ATG initiator codons as suggested by den Dunnen and Antonarakis et al. [2001] and per HGVS guidelines (www.hgvs.org).

The correlation of a mutation with an attenuated phenotype is based on four factors: 1) homozygosity of the mutation in the patients with attenuated phenotypes; 2) prediction from the likely structural change in the protein; 3) prediction from in vitro expression studies; and, 4) mutant allele permitting residual enzyme activity in primary fibroblasts or leukocytes, which would be dominant over an allele permitting no activity.

Figure 1.

Location of GUS gene mutations in MPS VII patients. The exons are presented by open boxes and the untranslated regions are filled boxes. Clinical phenotypes associated with missense or nonsense mutations are described.

Several mutations are recurrent. Among the recurrent mutations, the most prevalent are: c.526C>T (p.L176F), c.1244C>T (p.P415L), c.1222C>T (p.P408S), c.1856C>T (p.A619 V), c.646C>T (p.R216W), c.1144C>T (p.R382C), and c.1429C>T (p.R477W), accounting for 20.4, 4.9, 4.9, 4.9, 3.9, 3.9, and 3.9%, respectively [Tomatsu et al., 1990, 1991; Fukuda et al., 1991; Vervoort et al., 1993; Wu et al., 1994; Islam et al., 1996, 1998; Vervoort et al., 1996, 1997; Schwartz et al., 2003]. The p.L176F mutation has been identified in diverse ethnic populations while the p.P415L mutation and p.P415L/P408S double mutation, and the p.A619 V mutation have been detected only in Mexican and Japanese populations, respectively.

The most prevalent c.526C>T transitional mutation (p.L176F), originally found in two Mennonite siblings, was identified in 21 alleles of 11 patients from American (Caucasian), Brazilian, British, Chilean, French, Mexican, Polish, Spanish, and Turkish origins [Wu et al., 1994; Vervoort et al., 1996; Schwartz et al., 2003] (Sly, unpublished results). A total of 10 of 11 patients were homozygous for the mutation. Those homozygous patients developed an attenuated type of MPS VII with similar clinical symptoms and signs. The p.L176F conservative amino acid change generates a subtle structural alteration of GUS protein [Wu et al., 1994]. Although the cultured fibroblasts homozygous with p.L176F contained only 1.5 to 2.2% of normal GUS activity, overexpression of the p.L176F cDNA in COS cells produced 84% as much enzyme as the wild-type control cDNA. These findings suggested that overexpression can drive the folding reaction or the self-association of mutant monomers to formactive tetramers [Wu et al., 1994]. The mouse model corresponding with p.L176F was established and also showed an attenuated phenotype [Tomatsu et al., 2002b].

The p.P415L/p.P408S double point mutation and the p.A619 V mutation are of great interest since these mutations were specific to Mexican and Japanese populations, respectively [Tomatsu et al.,1990, 1991; Islam et al., 1996, 1998] (Sly, unpublished results). Both founder mutations are associated with an attenuated phenotype. The double mutant allele containing two C-to-T transitions resulting in p.P408S and p.P415L alterations was present in homozygous state in one Mexican patient and in heterozygous state in four. Expression of either of the mutations individually showed only modest effects on the properties of the enzyme. However, expression of the doubly mutant allele resulted in markedly reduced activity and rapid degradation in an early biosynthetic compartment (Table 4) [Islam et al., 1996]. Neither p.P408S nor p.P415L mutation was present alone in a normal Mexican population [Islam et al., 1998]. The p.A619 V mutation expressed 9.1% of normal cDNA in transfected COS cells. The residual activity of these expressed mutant proteins correlated with the attenuated phenotype for those mutations.

Table 4.

In Vitro Mutagenesis Data of GUSB Missense Mutations

| Mutation | Phenotype | Percentage of normal cDNA |

Location of the mutation |

Conservativeness of amino acid changes |

Evolutionary conservationa |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p.C38G | Attenuated | 7.0 | Surface | Nonconservative | 4 | Vervoort et al. [1998a] |

| p.S52F | Severe | 0.7 | Surface | Nonconservative | 2 | Vervoort et al. [1997] |

| p.G136R | Undefined | 0.6 | Surface | Nonconservative | 2 | Vervoort et al. [1996] |

| p.P148S | Severe | 1.2 | Hydrophobic core | Semiconservative | 1 | Yamada et al. [1995] |

| p.E150K | Severe | 4.0 | Hydrophobic core | Conservative | 1 | Vervoort et al. [1996] |

| p.D152N | Pseudodeficiency | 28 | Hydrophobic core | Conservative | 3 | Vervoort et al. [1995] |

| p.L176F | Attenuated | 84.1 | Hydrophobic core | Conservative | 1 | Wu et al. [1994] |

| p.R216W | Severe | 0.0 | Hydrophobic core | Nonconservative | 1 | Vervoort et al. [1996] |

| p.Y320C | Undefined | 1.4 | Hydrophobic core | Nonconservative | 1 | Vervoort et al. [1996] |

| p.Y320S | Severe | 1.0 | Hydrophobic core | Nonconservative | 1 | Vervoort et al. [1996] |

| p.K350N | Attenuated | 13 | Hydrophobic core | Nonconservative | 2 | Storch et al. [2003] |

| p.H351Y | Severe | 0.0 | Hydrophobic core | Semiconservative | 1 | Vervoort et al. [1996] |

| p.A354V | Attenuated | 37.7 | Hydrophobic core | Semiconservative | 4 | Wu and Sly [1993] |

| p.R374C | Undefined | 5.5 | Surface | Nonconservative | 2 | Vervoort et al. [1996] |

| p.R382C | Attenuated | 12.3 | Salt bridge | Nonconservative | 1 | Tomatsu et al. [1991] |

| p.R382H | Attenuated | 2.3 | Salt bridge | Conservative | 1 | Vervoort et al. [1996] |

| p.P408S | Attenuated | 61 | Hydrophobic core | Semiconservative | 2 | Islam et al. [1996] |

| p.P415L | Attenuated | 112 | Surface | Nonconservative | 4 | Islam et al. [1996] |

| p.R435P | Severe | 0.5 | Hydrophobic core | Nonconservative | 2 | Vervoort et al. [1996] |

| p.R477W | Severe | 0.7 | Hydrophobic core | Nonconservative | 1 | Vervoort et al. [1996] |

| p.Y495C | Severe | 0.8 | Surface | Nonconservative | 2 | Yamada et al. [1995] |

| p.Y508C | Attenuated | 19 | Surface | Nonconservative | 1 | Vervoort et al. [1996] |

| p.G572D | Severe | 2.1 | Hydrophobic core | Nonconservative | 4 | Vervoort et al. [1996] |

| p.R577L | Attenuated | 4.0 | Surface | Nonconservative | 2 | Storch et al. [2003] |

| p.K606N | Severe | 6.7 | Hydrophobic core | Nonconservative | 2 | Vervoort et al. [1996] |

| p.R611W | Severe | 0.0 | Hydrophobic core | Nonconservative | 1 | Wu and Sly [1993] |

| p.A619V | Attenuated | 9.1 | Hydrophobic core | Semiconservative | 1 | Tomatsu et al. [1990, 1991] Yamada et al. [1995] |

| p.Y626H | Attenuated | 4.0 | Hydrophobic core | Semiconservative | 1 | Vervoort et al. [1998a] |

| p.W627C | Attenuated | 39 | Surface | Nonconservative | 3 | Shipley et al. [1993] |

| p.P408S/ | Attenuated | 12.5 | Islam et al. [1996] | |||

| p.P415L | ||||||

| p.P649L | Polymorphism | 88.3 | Nonconservative | 4 | Tomatsu et al. [1991] |

1, conserved among all species; 2, vertebrate species; 3, mammalian species; 4, nonconserved.

The X-ray structure of the homotetrameric human GUS (332,000 Mr) was determined at 2.6-Å resolution [Jain et al., 1996]. The tetramer had approximate dihedral symmetry and each protomer consisted of three structural domains with topologies similar to a jelly roll barrel, an immunoglobulin constant domain and a triosephosphateisomerase (TIM) barrel, respectively. Residues 179–204 formed a beta-hairpin motif similar to the putative lysosomal targeting motif of cathepsin D. The active site of the enzyme was formed from a large cleft at the interface of two monomers. Residues Glu 451, Tyr 504, and Glu 540 were shown to be important for catalysis.

Using homology modeling among different species of GUS and β-galactosidase proteins, the potential effect of missense mutations on the GUS tertiary structure was estimated and the localization of the mutation site was correlated with the residual activity and the clinical phenotype (Fig. 4). Among 12 missense mutations with a severe phenotype, 10 of these mutations involve destruction of the hydrophobic core or modification of the packing (p.S52F, p.P148S, p.E150 K, p.R216W, p.Y320S, p.H351Y, p.R435P, p.R477W, p.Y495C, p.G572D, p.K606N, and p.R611W). On the other hand, 5 out of 7 mutations located on the surface of the GUS protein (p.C38G, p.P415L, p.Y508C, p.R577L, and p.W627C) were associated with attenuated phenotypes. However, two mutations on the surface (p.S52F and p.Y495C) were associated with severe phenotypes. These two mutations are nonconservative amino acid changes that, despite their location on the surface, disrupt the tertiary structure and result in a severe phenotype. On the other hand, mutations such as p.D152N, p.L176F, p.A354 V, p.R382 H, p.P408S, p.A619 V, and p.Y626 H are located on either the hydrophobic core or involve a salt bridge [Jain et al., 1996], and represent conservative or semiconservative amino acid changes that lead to attenuated phenotypes.

A total of 28 mutations, one pseudodeficiency, and one benign polymorphism were analyzed by in vitro transient overexpression. We used COS cells for 23 mutations, MPS VII fibroblasts for three mutations, and BHK cells for two mutations (Table 4). GUS activity was determined using 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-glucuronide as a substrate. A total of 8 out of 11 mutants associated with the severe phenotype had under 3% of normal cDNA GUS activity (mean, 1.5%) while 13 out of 14 mutants found in patients with the attenuated phenotype had higher than 3% of normal activity (3–112% of wild-type GUS activity; mean, 32.8%), indicating a positive correlation between the transient expression level and the clinical phenotype [Tomatsu et al., 1990, 1991; Shipley et al., 1993; Wu and Sly, 1993; Vervoort et al., 1995, 1996, 1998a; Yamada et al.,1995; Storch et al., 2003]. One patient with an attenuated phenotype had 2.3% of wild-type activity in COS cells.

The G-to-A transition (c.454G>A) in the coding region of the GUS gene, which resulted in an aspartic-acid-to-asparagine substitution at amino acid position 152 (p.D152N), produced a pseudodeficiency allele that leads to greatly reduced levels of GUS activity in vitro without apparent deleterious consequences [Vervoort et al., 1998a]. The c.454G>A mutation was found initially in the pseudodeficient mother of a child with MPS VII, but it was not on her disease-causing allele, which carried the p.L176F mutation. Screening of 100 unrelated normal individuals for the c.454G>A mutation with a PCR method detected one carrier (a rough estimate of frequency: 0.5%). Reduced GUS activity following transfection of COS cells with the p.D152N cDNA supported the causal relationship between the p.D152N allele and pseudodeficiency. The mutation reduced the fraction of expressed enzyme that was secreted. Pulse-chase experiments indicated that the reduced activity in COS cells was due to accelerated intracellular turnover of the p.D152N enzyme [Vervoort et al., 1998a]. The presence of the p.D152N mutation in combination with certain other MPS VII mutations might be more deleterious.

Nonsense Mutations

A total of six nonsense mutations have been reported: c.328C>T (p.R110X), c.935C>G (p.S312X), c.1069C>T (p.R357X), c.1337G>A (p.W446X), c.1520G>A (p.W507X), and c.1521G>A (p.W507X) (Table 1) [Shipley et al., 1993; Yamada et al., 1995; Vervoort et al., 1996, 1997, 1998a] (Sly, unpublished results). All of them should result in synthesis of truncated proteins without catalytic activity, predicting a severe phenotype in MPS VII. The second most frequent p.R357X mutation derived from a C-to-T transition at a CpG site occurred in diverse ethnic backgrounds suggesting a true recurrent mutation [Shipley et al., 1993; Vervoort et al., 1996, 1997] (Sly, unpublished results). Other nonsense mutations were sporadic and observed in only one patient.

Splice-Site Mutations

Two splice-site mutations including one novel mutation at the donor site of intron 3 (c.581+1G>A) were identified in the GUS gene (Table 1). One (c.1244+1G>A) is a homozygous mutation while the other one is in a compound heterozygote. Both splicing-site mutations in the GUS gene disrupt the consensus sequence between exon and intron. Both mutations at the acceptor site cause complete deletion of the following exons. Skipping an exon would result in a frameshift and the appearance of a premature stop codon (p.K194fsX22, p.P415fsX1) and/or absence of a GUS active catalytic site (E540).

In accordance with this prediction, a patient homozygous for the C1244+1 G-to-A splice-site mutation developed a severe form of MPS VII and showed a complete loss of GUS activity in fibroblasts [Vervoort et al., 1997] (Sly unpublished results).

Deletions

A total of five deletions were identified so far in the GUS gene (Table 1) (c.1081_1107del27, c.1454_1457del4, c.1616_1653del38, c.1775delT, and c.1874_1875delGA). Four deletions cause frameshifts (c.1454_1457del4, c.1616_1653del38, c.1775delT, and c.1874_1875delGA) and the appearance of premature truncation codons (p.S485fsX13, p.S539RfsX7, p.F592SfsX2, and p.R625IfsX6, respectively), probably leading to nonsense-mediated decay of the mRNA and a complete loss of GUS activity in the affected cells. Patients homozygous for the c.1081_1107del27 in-frame mutation manifested a severe form of MPS VII [Vervoort et al., 1997]. The mechanism of the c.1616_1653del38 deletion was unique. The patient was a compound heterozygote of p.W507X and a 38-bp deletion at position 1616–1653 in exon 10. The 38-bp deletion was caused by a C-to-T transition in exon 10 that generates a new, premature 5′ splice-site. The resulting nucleotide sequence AGA/GTGAGT has a close homology to the 5′ splice consensus sequence (A or C) AG/GT (A or G) AGT. This alteration interferes with normal splicing of the GUS gene transcript by forming a novel 5′ splice-site.

Slipped mispairing can in principle account for the generation of 4 out of 5 deletions because of a run of identical bases or direct repeat (2 bp or more) (c.1081_1107del27, c.1454_1457del4, c.1775delT, and c.1874_1875delGA).

Vervoort et al. [1998b] reported a patient with an attenuated phenotype whose paternal allele (IVS8+0.6kbdelTC) (Table 3) was claimed to create a new donor splice-site that activated a cryptic exon in an Alu-element of the GUS gene and led to skipping of exon 9. This allele confers the alternate phenotype, since the maternal allele (p.W446X) is a null allele (Table 1).

No insertions were identified so far in the GUS gene. The GUS gene spans approximately 20 kb, in addition to the 1-kb promoterregion located at 7q11.21, and contains 37 Alu repeats [Miller et al., 1990; Shipley et al., 1991; Speleman et al., 1996]. Neither large deletions nor rearrangement were identified. Alu repeats represented around 45% of the entire GUS gene (8.8 kb of 19.5 kb in total length), showing an extremely high percentage of Alu elements compared with the human genome (representing 6–12%). In addition, over 20 pseudogenes of GUS gene were observed in the entire human genome. Nevertheless, no large rearrangement has been reported so far.

Polymorphisms

A total of two benign genetic variants in the coding regions of the GUS gene have been reported (Table 2) [Tomatsu et al., 1991; Wu et al., 1994; Vervoort et al., 1995, 1998a]. One polymorphism changing an amino acid residue was identified in the normal population (c.1946C>T, p.P649L). An in vitro expression study showed that this polymorphism provides 88.3% of normal GUS cDNA activity.

Relations Among Genotypes and Phenotypes

The genotype/phenotype correlation for each of 38 single-nucleotide alterations has been examined based upon the following four factors (Tables 1, 3, and 4): 1) the phenotype of the patient homozygous for the mutation; 2) the level of activity by in vitro expression study; 3) prediction of the likely change in the protein structure; and 4) the presence of a second allele permitting residual enzyme activity, which would be dominant over an allele permitting no activity. In all, 15 mutations were associated with a severe phenotype, 14 mutations were associated with an attenuated phenotype, and one with a normal phenotype (pseudodeficiency allele). The other seven mutations were not defined by the current information. A total of 5 out of 6 nonsense mutations and 4 out of 5 deletions were associated with severe phenotypes. One splicing site mutation was associated with a severe phenotype and the other was not defined.

Clinical and Diagnostic Relevance

Clinical diagnosis is based on findings typical of an MPS disorder, including developmental delay and mental retardation, dysostosis multiplex, hepatosplenomegaly, and short stature. Biochemical diagnosis is based on demonstrating a deficiency of GUS in serum, leukocyte lysates, or cultured fibroblasts [Glaser and Sly, 1973]. This assay is included in the diagnostic panel of most biochemical genetics laboratories. Genetests.org lists 14 laboratories that offer diagnostic testing, three of which also offer sequence analysis of the coding region. Molecular diagnosis and mutational analysis is possible by direct sequencing of mRNA following RT-PCR [Tomatsu et al., 1991; Shipley et al., 1993; Vervoort et al., 1996]. Genomic sequencing is more challenging because of multiple unprocessed pseudogenes, but Shipley et al. [1993] described conditions of amplifying and characterizing genomic sequences of the true GUS gene, despite the background of related sequences.

The analysis of GUS mutations in MPS VII reveals considerable molecular heterogeneity, reflecting the diversity of clinical phenotypes. A total of 5 out of 49 unique mutations occurred over five times, accounting for 36.9% of all the analyzed mutant alleles. The most prevalent mutation, p.L176F, accounted for 20.4% of the analyzed mutant alleles. For diagnosis and prognosis in MPS VII, molecular testing should follow direct enzyme assay in leukocytes and cultured skin fibroblasts. The patients’ clinical severity generally can be correlated with their genotype, the predicted effect of missense mutations on the tertiary structure of the enzyme, and the residual activity by in vitro expression study. Many of the reported patients had the severe form of MPS VII. These patients mainly demonstrate frameshifts or other mutations resulting in premature truncations, as well as deletions and splicing-site mutations. Other severe patients had missense mutations affecting conserved amino acid residues in the hydrophobic core or active site region for maintaining the tertiary structure of the protein.

Patients who are compound heterozygotes, having a combination of an attenuated and a severe mutation, manifest clinically milder symptoms than patients homozygous for a severe mutation. It appears that only a small percentage of normal GUS activity provided by one allele (2–3%) can protect against severe phenotypes. The protective effect provided by small amounts of enzyme activity from enzyme replacement and/or gene therapies augers well for effective treatments for MPS VII in the future.

MPS VII Models

Seven murine, one feline, and one canine model of MPS VII are now available to experimentally test pharmaceutical agents, bone marrow transplantation, ERT, and gene therapy (Table 5). These models result from missense mutations or deletions in the GUS gene, which are responsible for over 95% of mutant human alleles. These models should greatly contribute to evaluating the effectiveness of treatment.

Table 5.

Animal Models of MPS VII*

| Animal | Description | Base changea | Amino acid change | Phenotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Murine | gusmps/gusmps | c.1470delC | mP490RfsX8 | Severe |

Birkenmeier et al. [1989]; Sands and Birkenmeier [1993] |

| Murine | gusmps2J/gusmps2J | Intron 8 ins5.4-kb | NDb | Attenuated |

Gwynn B et al. [1998]; Vogler et al. [2001] |

| Murine | MPSVII/E540ATg | c.1470delC + ins hGUSBcDNA with c.1618A>C |

p.E540A · mP490RfsX8 | Severe | Sly et al. [2001] |

| Murine | Gustm(hE540A · mE536A)Sly | c.1606A>C + intron 9 ins hGUSBcDNA with c.1618A>C |

p.E540A · mE536A | Severe | Tomatsu et al. [2003b] |

| Murine | Gustm(E536A)Sly | c.1606A>C | mE536A | Severe | Tomatsu et al. [2002b] |

| Murine | Gustm(E536Q)Sly | c.1607G>C | mE536Q | Attenuated | Tomatsu et al. [2002b] |

| Murine | Gustm(L175F)Sly | c.523C>T | mL175F | Attenuated | Tomatsu et al. [2002b] |

| Feline | NA | c.1074G>A | fE351K | Severe |

Gitzelmann et al. [1994]; Fyfe et al. [1999] |

| Canine | NA | c.559G>A | cR166H | Severe |

Haskins et al. [1984]; Haskins et al. [1991]; Ray et al. [1998] |

| Canine | NA | c.559G>A | cR166H | Severe | Silverstein et al. [2004] |

The numbers for the nucleotide changes are reported in accordance with GenBank entry human: NM_010368.1, NP_034498.1; murine: NM_010368.1, NP_034498.1; feline: NM_001003910.1, NP_001003910.1; canine: NM_001003191.1, NP_001003191.1.

The DNA mutation numbering is based on cDNA sequence. Nucleotides are numbered from the ATG initiation codon as suggested by den Dunnen and Antonarakis et al. [2001] and per HGVS guidelines (www.hgvs.org).

NA, not available.

The original natural MPS VII murine model, gusmps/mps, showed a 1-bp deletion (c.1470delC), which created a frameshift mutation in exon 10. This frameshift mutation introduces a premature stop codon at codon 497 in exon 10 (mP490RfsX8) and explains the molecular, biochemical, and pathological abnormalities associated with the gusmps/mps phenotype [Birkenmeier et al., 1989; Sands and Birkenmeier, 1993]. The second natural MPS VII mouse model, gusmps2J/mps2J, is deficient in GUS because of insertion of an intracisternal A particle element into intron 8 of the gus structural gene. Mice with the gusmps2J/mps2J genotype had <1% of normal GUS activity and secondary elevations of other lysosomal enzymes. The phenotype includes shortened life-span, dysmorphic features, and skeletal dysplasia. Lysosomal storage of GAGs is widespread and affects the brain, skeleton, eye, ear, heart valves, aorta, and the fixed tissue macrophage system. Thus the phenotypic and pathologic alterations in gusmps2J/mps2J mice are similar to those in patients with MPS VII although milder than those in gusmps/mps mice [Gwynn et al., 1998; Vogler et al., 2001].

To enhance the value of the gusmps/mps model for enzyme and gene therapy using the human GUS gene product, we produced a transgenic mouse expressing the human GUS cDNA with an amino acid substitution at the active site nucleophile (p.E540A) and bred it onto the MPS VII (gusmps/mps) background [Sly et al., 2001]. The mutant mice expressed the inactive human GUS from the mutant human transgene. We also used homologous recombination to simultaneously introduce a human cDNA transgene expressing inactive human GUS (p.E540A) into intron 9 of the murine Gus gene and a targeted active site mutation (mE536A) into the adjacent exon 10 [Tomatsu et al., 2003]. These two models retained the clinical, morphological, biochemical, and histopathological characteristics of the original MPS VII (gusmps/mps) mouse. However, they were now tolerant to immune challenge with human GUS. These tolerant MPS VII mouse models became useful for preclinical trials evaluating the effectiveness of enzyme and/or gene therapy with the human gene products likely to be administered to human patients with MPS VII [Vogler et al., 2001].

To study missense mutant models of murine MPS VII with phenotypes of varying severity, we used targeted mutagenesis to produce mE536A and mE536Q, corresponding to active-site nucleophile replacements p.E540A and p.E540Q in human GUS, and also mL175F, corresponding to the most common human mutation, p.L176F. The mE536A mouse had no GUS activity in any tissue and displayed a severe phenotype like that of the originally described MPS VII mice carrying a deletion mutation (gusmps/mps). The mE536Q and mL175F mice had low levels of residual activity and milder phenotypes [Tomatsu et al., 2002b].

In the MPS VII feline model, there was a G-to-A transition in the affected feline cDNA (c.1074G>A) that predicted a fE351 K substitution, and eliminated GUS enzyme activity in expression studies. Multiple species comparisons with the crystal structure of human GUS indicated that E351 is a highly conserved residue most likely essential in maintenance of the enzyme’s conformation [Fyfe et al., 1999]. An affected male cat 12–14 weeks old had walking difficulties and an enlarged abdomen. Other findings included facial dysmorphism, plump paws, corneal clouding, granulation of neutrophils, vacuolated lymphocytes, and a positive urine test for sulfated GAGs. Thus, the MPS VII cat had the phenotypic characteristics of human MPS VII patients [Gitzelmann et al., 1994].

In the MPS VII dog model, the G-to-A change at nucleotide position 559 in the affected canine cDNA sequence (c.559G>A) causes a cR166 H mutation. Introduction of the G-to-A substitution at position 559 into the normal canine GUS cDNA nearly eliminated the GUS enzyme activity expressed in mammalian cells [Haskins et al., 1984, 1991; Ray et al., 1998]. The same cR166 H mutation was found in another German shepherd dog [Silverstein et al., 2004]. This 12-week-old male German shepherd dog was evaluated because of a 3-week history of a progressive inability to ambulate. Clinical and laboratory findings included skeletal deformities, corneal cloudiness, cytoplasmic granules in the neutrophils and lymphocytes of blood and CSF, and GAGs in a urine sample.

Future Prospects

Improvements in diagnostic techniques should allow identification of uncharacterized mutations in MPS VII patients (8% of mutant alleles are undefined). To date, most investigations have been carried out by PCR-mediated strategies and subsequent analysis by direct sequencing. Large and complex rearrangements, deletions, inversions, or mutations in the intronic sequence of the GUS gene escape detection by the published PCR-based strategies. These mutations might be detected by array comparative genomic hybridization [Lu et al., 2007].

Defining the genotype/phenotype relationship remains one of the most challenging tasks for MPS VII professionals since the clinical manifestations of MPS VII patients are so variable. Still needed are long-term clinical observations as well as attempts to characterize the modifying factors that influence phenotype, posttranslational processing and stabilization of the mutant enzymes, and the efficient catabolism of DS, HS, and CS.

Longitudinal studies require a larger number of cases of the same age and genotype to clarify the relationship between genotype, the chemical phenotype in blood and urine DS, HS, and CS levels, and the clinical course. Additionally, investigations on the relationship between the GUS residual activity in MPS VII patients and accumulation of each GAG, particularly in bone and brain, will provide more precise information about the mechanisms causing systemic bone dysplasia and central nervous system (CNS) involvement in each mutant form, and may provide a rational basis for more efficient treatment.

Finally, recent development of identification of each GAG by tandem mass spectrometry will facilitate screening for MPS VII and monitoring therapy [Oguma et al., 2007]. These techniques will also enhance prospects for newborn screening for lysosomal storage disorders (LSDs), the importance of which is emphasized by the correlation between early treatment and favorable response to therapy.

Figure 2.

Multiple amino acid alignment of GUS from human (Hosa-GUS), chimpanzee (Patr-GUS), cow (Bota-GUS), pig (Susc-GUS), dog (Cafa-GUS), mouse (Mumu-GUS), rat (Rano-GUS), chicken (Gaga-GUS), frog (Xetr-GUS), fruit fly (Drme-GUS), mosquito (Anga-GUS), honey bee (Apme-GUS), red flour beetle (Trca-GUS), nematode (Cael-GUS), gram-positive bacteria (Arsp.-GUS), enterobacteria (Esco-GUS), and fungi (Scsp.-GUS), along with bacterial β-galactosidase (Esco-β-Gal). The arrow indicates the active site (residue E540) of human GUS. GenBank reference sequences: Homo sapiens, NM_010368.1, NP_034498.1; Pan troglodytes, XP_001138789.1; Macaca mulata, XM_001087699; Mus musculus, NM_010368.1, NP_034498.1; Rattus norvegicus, NP_058711; Felis catus, NM_001009310.1, NP_001009310.1; Canis familiaris, NM_001003191.1, NP_001003191.1; Bos taurus, NM_001083436.1; Sus scrofa, AK232674.1; Gallus gallus, NP_001034405; Xenopus tropicalis, CT030620; Danio renio, XM_695030; Drosophila melanogaster, NP_001014535.1; Anopheles gambiae, XP_320660.2; Apis mellifera, XM_393305; Tribolium castaneum, XM_964260.1; Caenorhabditis elegans, NP_493548.1; Arthrobacter sp., RP10, AAV91790; Scopulariopsis sp., RP38.3, AAV91788; Escherichia coli, AAB30197.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tracey Baird for editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript. W.S.S. and J.H.G. were also supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM34182.

Contract grant sponsor: Austrian Research Society for Mucopolysaccharidoses and Related Diseases; German MPS Society; Italian MPS Society; National MPS Society

References

- Antonarakis SE, Krawczak M, Cooper DN. The nature and mechanisms of human gene mutation. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, editors. The metabolic and molecular bases of inherited disease. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2001. pp. 343–377. [Google Scholar]

- Birkenmeier EH, Davisson MT, Beamer WG, Ganschow RE, Vogler CA, Gwynn B, Lyford KA, Maltais LM, Wawrzyniak CJ. Murine mucopolysaccharidosis type VII. Characterization of a mouse with beta-glucuronidase deficiency. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:1258–1266. doi: 10.1172/JCI114010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brot FE, Bell CE, Jr, Sly WS. Purification and properties of beta-glucuronidase from human placenta. Biochemistry. 1978;17:385–391. doi: 10.1021/bi00596a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda S, Tomatsu S, Sukegawa K, Sasaki T, Yamada Y, Kuwahara T, Okamoto H, Ikedo Y, Yamaguchi S, Orii T. Molecular analysis of mucopolysaccharidosis type VII. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1991;14:800–804. doi: 10.1007/BF01799953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyfe JC, Kurzhals RL, Lassaline ME, Henthorn PS, Alur PR, Wang P, Wolfe JH, Giger U, Haskins ME, Patterson DF, Sun H, Jain S, Yuhki N. Molecular basis of feline beta-glucuronidase deficiency: an animal model of mucopolysaccharidosis VII. Genomics. 1999;58:121–128. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitzelmann R, Bosshard NU, Superti-Furga A, Spycher MA, Briner J, Wiesmann U, Lutz H, Litschi B. Feline mucopolysaccharidosis VII due to beta-glucuronidase deficiency. Vet Pathol. 1994;31:435–443. doi: 10.1177/030098589403100405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser JH, Sly WS. Beta-glucuronidase deficiency mucopolysaccharidosis: methods for enzymatic diagnosis. J Lab Clin Med. 1973;82:969–977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwynn B, Lueders K, Sands MS, Birkenmeier EH. Intracisternal A-particle element transposition into the murine beta-glucuronidase gene correlates with loss of enzyme activity: a new model for beta-glucuronidase deficiency in the C3 H mouse. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6474–6481. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskins ME, Desnick RJ, DiFerrante N, Jezyk PF, Patterson DF. Beta-glucuronidase deficiency in a dog: a model of human mucopolysaccharidosis VII. Pediatr Res. 1984;18:980–984. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198410000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskins ME, Aguirre GD, Jezyk PF, Schuchman EH, Desnick RJ, Patterson DF. Mucopolysaccharidosis type VII (Sly syndrome). Beta-glucuronidase-deficient mucopolysaccharidosis in the dog. Am J Pathol. 1991;138:1553–1555. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrissat B. A classification of glycosyl hydrolases based on amino acid sequence similarities. Biochem J. 1991;280(Pt 2):309–316. doi: 10.1042/bj2800309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam MR, Vervoort R, Lissens W, Hoo JJ, Valentino LA, Sly WS. beta-Glucuronidase P408S, P415L mutations: evidence that both mutations combine to produce an MPS VII allele in certain Mexican patients. Hum Genet. 1996;98:281–284. doi: 10.1007/s004390050207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam MR, Arreola MP Gallegos, Wong P, Tomatsu S, Corona JS, Sly WS. Beta-glucuronidase P408S, P415L allele in a Mexican population: population screening in Guadalajara and prenatal diagnosis. Prenat Diagn. 1998;18:822–825. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0223(199808)18:8<822::aid-pd361>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam MR, Tomatsu S, Shah GN, Grubb JH, Jain S, Sly WS. Active site residues of human beta-glucuronidase. Evidence for Glu(540) as the nucleophile and Glu(451) as the acid-base residue. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23451–23455. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S, Drendel WB, Chen ZW, Mathews FS, Sly WS, Grubb JH. Structure of human beta-glucuronidase reveals candidate lysosomal targeting and active-site motifs. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:375–381. doi: 10.1038/nsb0496-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczak M, Ball EV, Cooper DN. Neighboring-nucleotide effects on the rates of germ-line single-base-pair substitution in human genes. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:474–488. doi: 10.1086/301965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Shaw CA, Patel A, Li J, Cooper ML, Wells WR, Sullivan CM, Sahoo T, Yatsenko SA, Bacino CA, Stankiewicz P, Ou Z, Chinault AC, Beaudet AL, Lupski JR, Cheung SW, Ward PA. Clinical implementation of chromosomal microarray analysis: summary of 2513 postnatal cases. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e327–e337. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RD, Hoffmann JW, Powell PP, Kyle JW, Shipley JM, Bachinsky DR, Sly WS. Cloning and characterization of the human beta-glucuronidase gene. Genomics. 1990;7:280–283. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(90)90552-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oguma T, Tomatsu S, Montano AM, Okazaki O. Analytical method for the determination of disaccharides derived from keratan, heparan, and dermatan sulfates in human serum and plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography/turbo ionspray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 2007;368:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima A, Kyle JW, Miller RD, Hoffmann JW, Powell PP, Grubb JH, Sly WS, Tropak M, Guise KS, Gravel RA. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of cDNA for human beta-glucuronidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:685–689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.3.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray J, Bouvet A, DeSanto C, Fyfe JC, Xu D, Wolfe JH, Aguirre GD, Patterson DF, Haskins ME, Henthorn PS. Cloning of the canine beta-glucuronidase cDNA, mutation identification in canine MPS VII, and retroviral vector-mediated correction of MPS VII cells. Genomics. 1998;48:248–253. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.5189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sands MS, Birkenmeier EH. A single-base-pair deletion in the beta-glucuronidase gene accounts for the phenotype of murine mucopolysaccharidosis type VII. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6567–6571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz I, Silva LR, Leistner S, Todeschini LA, Burin MG, Pina-Neto JM, Islam RM, Shah GN, Sly WS, Giugliani R. Mucopolysaccharidosis VII: clinical, biochemical and molecular investigation of a Brazilian family. Clin Genet. 2003;64:172–175. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2003.00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipley JM, Miller RD, Wu BM, Grubb JH, Christensen SG, Kyle JW, Sly WS. Analysis of the 5′ flanking region of the human beta-glucuronidase gene. Genomics. 1991;10:1009–1018. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(91)90192-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipley JM, Klinkenberg M, Wu BM, Bachinsky DR, Grubb JH, Sly WS. Mutational analysis of a patient with mucopolysaccharidosis type VII, and identification of pseudogenes. Am J Hum Genet. 1993;52:517–526. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein D, Carmichael KP, Wang P, O’Malley TM, Haskins ME, Giger U. Mucopolysaccharidosis type VII in a German Shepherd Dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2004;224:553–553. doi: 10.2460/javma.2004.224.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sly WS, Quinton BA, McAlister WH, Rimoin DL. Beta glucuronidase deficiency: report of clinical, radiologic, and biochemical features of a new mucopolysaccharidosis. J Pediatr. 1973;82:249–257. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(73)80162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sly WS, Vogler C, Grubb JH, Zhou M, Jiang J, Zhou XY, Tomatsu S, Bi Y, Snella EM. Active site mutant transgene confers tolerance to human beta-glucuronidase without affecting the phenotype of MPS VII mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2205–2210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051623698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speleman F, Vervoort R, Van Roy N, Liebaers I, Sly WS, Lissens W. Localization by fluorescence in situ hybridization of the human functional beta-glucuronidase gene (GUSB) to 7q11.21 -> q11.22 and two pseudogenes to 5p13 and 5q13. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1996;72:53–55. doi: 10.1159/000134161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch S, Wittenstein B, Islam R, Ullrich K, Sly WS, Braulke T. Mutational analysis in longest known survivor of mucopolysaccharidosis type VII. Hum Genet. 2003;112:190–194. doi: 10.1007/s00439-002-0849-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomatsu S, Sukegawa K, Ikedo Y, Fukuda S, Yamada Y, Sasaki T, Okamoto H, Kuwabara T, Orii T. Molecular basis of mucopolysaccharidosis type VII: replacement of Ala619 in beta-glucuronidase with Val. Gene. 1990;89:283–287. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90019-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomatsu S, Fukuda S, Sukegawa K, Ikedo Y, Yamada S, Yamada Y, Sasaki T, Okamoto H, Kuwahara T, Yamaguchi S, Kiman T, Shintaku H, Isshiki G, Orii T. Mucopolysaccharidosis type VII: characterization of mutations and molecular heterogeneity. Am J Hum Genet. 1991;48:89–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomatsu S, Orii KO, Islam MR, Shah GN, Grubb JH, Sukegawa K, Suzuki Y, Orii T, Kondo N, Sly WS. Methylation patterns of the human beta-glucuronidase gene locus: boundaries of methylation and general implications for frequent point mutations at CpG dinucleotides. Genomics. 2002a;79:363–375. doi: 10.1006/geno.2002.6706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomatsu S, Orii KO, Vogler C, Grubb JH, Snella EM, Gutierrez MA, Dieter T, Sukegawa K, Orii T, Kondo N, Sly WS. Missense models [Gust-m(E536A)Sly, Gustm(E536Q)Sly, and Gustm(L175F)Sly] of murine mucopolysaccharidosis type VII produced by targeted mutagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002b;99:14982–14987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232570999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomatsu S, Orii KO, Vogler C, Grubb JH, Snella EM, Gutierrez M, Dieter T, Holden CC, Sukegawa K, Orii T, Kondo N, Sly WS. Production of MPS VII mouse (Gus(tm(hE540A x mE536A)Sly)) doubly tolerant to human and mouse beta-glucuronidase. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:961–973. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vervoort R, Lissens W, Liebaers I. Molecular analysis of a patient with hydrops fetalis caused by beta-glucuronidase deficiency, and evidence for additional pseudogenes. Hum Mutat. 1993;2:443–445. doi: 10.1002/humu.1380020604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vervoort R, Islam MR, Sly W, Chabas A, Wevers R, de Jong J, Liebaers I, Lissens W. A pseudodeficiency allele (D152N) of the human beta-glucuronidase gene. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;57:798–804. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vervoort R, Islam MR, Sly WS, Zabot MT, Kleijer WJ, Chabas A, Fensom A, Young EP, Liebaers I, Lissens W. Molecular analysis of patients with beta-glucuronidase deficiency presenting as hydrops fetalis or as early mucopoly-saccharidosis VII. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:457–471. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vervoort R, Buist NR, Kleijer WJ, Wevers R, Fryns JP, Liebaers I, Lissens W. Molecular analysis of the beta-glucuronidase gene: novel mutations in mucopolysaccharidosis type VII and heterogeneity of the polyadenylation region. Hum Genet. 1997;99:462–468. doi: 10.1007/s004390050389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vervoort R, Gitzelmann R, Bosshard N, Maire I, Liebaers I, Lissens W. Low beta-glucuronidase enzyme activity and mutations in the human beta-glucuronidase gene in mild mucopolysaccharidosis type VII, pseudodeficiency and a heterozygote. Hum Genet. 1998a;102:69–78. doi: 10.1007/s004390050656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vervoort R, Gitzelmann R, Lissens W, Liebaers I. A mutation (IVS810.6kbdelTC) creating a new donor splice site activates a cryptic exon in an Alu-element in intron 8 of the human beta-glucuronidase gene. Hum Genet. 1998b;103:686–693. doi: 10.1007/pl00008709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogler C, Barker J, Sands MS, Levy B, Galvin N, Sly WS. Murine mucopolysaccharidosis VII: impact of therapies on the phenotype, clinical course, and pathology in a model of a lysosomal storage disease. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2001;4:421–433. doi: 10.1007/s10024001-0079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong AW, He S, Grubb JH, Sly WS, Withers SG. Identification of Glu-540 as the catalytic nucleophile of human beta-glucuronidase using electrospray mass spectrometry. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:34057–34062. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.34057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu BM, Sly WS. Mutational studies in a patient with the hydrops fetalis form of mucopolysaccharidosis type VII. Hum Mutat. 1993;2:446–457. doi: 10.1002/humu.1380020605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu BM, Tomatsu S, Fukuda S, Sukegawa K, Orii T, Sly WS. Overexpression rescues the mutant phenotype of L176F mutation causing beta-glucuronidase deficiency mucopolysaccharidosis in two Mennonite siblings. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:23681–23688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada S, Tomatsu S, Sly WS, Islam R, Wenger DA, Fukuda S, Sukegawa K, Orii T. Four novel mutations in mucopolysaccharidosis type VII including a unique base substitution in exon 10 of the beta-glucuronidase gene that creates a novel 5′-splice site. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:651–655. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.4.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]