Abstract

Background

Ghrelin, the only identified circulating orexigenic signal, is unique in structure in which a specific acyl-modification of its third serine occurs. This acylation is necessary for ghrelin to bind to its receptor and to exert its biologic activity, which is catalyzed by ghrelin O-acyltransferase (GOAT). Although ghrelin is mainly secreted from gastric X/A like endocrine cells, it is also expressed in pancreatic islet cells and regulates insulin secretion. In this study, we examined the expression and regulation of GOAT in pancreas.

Methods

GOAT mRNA and immunoreactivity were examined in pancreatic islets and INS-1 cells by RT-PCR and immunofluorescent staining or Western blotting.

Results

Insulin inhibits the expression of GOAT mRNA and GOAT promoter activity in a dose and time-dependent manner. The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is activated by insulin. Blocking mTOR signaling by either rapamycin or overexpression of its negative regulator tuberous sclerosis complex 1 (TSC1) or TSC2 attenuates the inhibitory effect of insulin on the transcription and translation of GOAT.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that GOAT is present in pancreatic islet cells and that insulin inhibits the expression of GOAT via the mediation of mTOR signaling.

Key Words: Ghrelin O-acyltransferase, Insulin, Pancreatic islet cells, Mammalian target of rapamycin

Introduction

Ghrelin is a 28 amino acid peptide hormone which is secreted primarily by the stomach [1]. Initial studies of ghrelin focused on the role of ghrelin as a circulating orexigenic signal. However, in addition to its actions to regulate growth hormone release, food intake and energy homeostasis, effects of ghrelin on gastrointestinal, pancreatic, cardiovascular, pulmonary, immune, neuronal functions, myogenesis and adipogenesis have also been described [2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]. Recently, ghrelin has been implicated in modulation of glucose homeostasis [8, 9]. Ghrelin- expressing ε-cells are present within pancreatic islets. The number of ghrelin-positive ε-cells is greater in transgenic mouse models lacking functional Nkx2-2, Pax6 or Pax4, with reciprocal β-cell deficiency [10]. Despite the co-location of ε-cells and β-cells in pancreatic islets, it is currently unknown whether insulin affects the function of ε-cells.

The structure of ghrelin is unique in that specific acyl-modification of its third serine occurs. This acylation is necessary for ghrelin to bind to the ghrelin receptor, growth hormone secretagogue receptor (GHSR1a), and to exert biologic activity [2]. The carboxylic chain that esterifies the hydroxyl of serine is primarily n-octanoic acid, but other 6–10 carbon chain residues may also modify the structure of ghrelin. The enzyme responsible for the acylation of ghrelin was identified in 2008 and named ghrelin O-acyltransferase (GOAT) [11, 12]. GOAT is a porcupine-like enzyme belonging to the family of membrane-bound O-acyltransferases (MBOAT), typically localizing within the endoplasmic reticulum. Human GOAT is expressed in both stomach and pancreas [11]. Human GOAT can acylate ghrelin with carboxylic acids ranging from acetate to tetradecanoic acid, in addition to octanoate. Information on the regulation of GOAT expression is still limited.

The present study examines the presence of GOAT in pancreatic islet cells and the mechanism by which insulin modulates the expression of GOAT in islet cells. Insulin inhibits the transcription and translation of pancreatic GOAT via a mechanism involving the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway.

Materials and Methods

Animals and chemicals

Male C57BL/6J mice and Sprague Dawley rats (8-week old) were housed in standard rodent cages and maintained in a regulated environment (24°C, 12:12h light: dark cycle with lights on at 7:00 AM). Regular chow and water were available ad libitum unless specified otherwise. These investigations conformed with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85–23, revised 1996) and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Peking University.

Rapamycin, mouse anti-β-actin antibody, goat anti-insulin antibody, chicken anti-rabbit FITC-conjugated IgG and donkey anti-goat Texas Red-conjugated IgG were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Dimethylsulfoxide, hoechst 33258 and leucine were from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO). Protease inhibitor cocktail was purchased from Amersham Biosciences (Pittsburgh, PA). Pathscan multiplex western cocktail I, Phospho-Akt pathway sample kit, Phospho-Tuberin/TSC2 (Thr1462) rabbit mAb, Tuberin/TSC2 rabbit mAb, Phospho-mTOR (Ser2448) rabbit mAb and mTOR rabbit mAb were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Rabbit anti-GOAT antibody was from Phoenix Pharmaceuticals (Burlingame, CA). IRDye-conjugated affinity-purified anti- rabbit, anti-mouse IgGs were purchased from Rockland (Gilbertsville, PA). Trizol reagent, the reverse transcription system, luciferase assay kit and β-galactosidase enzyme assay kit were from Promega (Madison, WI). Lipofectamine and collagenase IV were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

Tissue sample preparations and immunofluorescent analysis

C57BL/6J mice or Sprague Dawley rats were deeply anesthetized using pentobarbital. The whole stomach and pancreas were quickly removed and rinsed thoroughly with PBS. The tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated, embedded in wax, and sectioned at 6 μm. Paraffin-embedded sections were de-waxed, re-hydrated, and rinsed in PBS. After boiling for 10 min in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0), sections were blocked in 1% BSA in PBS for 1 h at room temperature, then incubated overnight with rabbit anti-GOAT (1:400) antibody alone or a mixture of rabbit anti-GOAT (1:400) and goat anti-insulin (1:100) antibodies. Tissue sections were then incubated at 22°C for 2 h with the following secondary antibodies: chicken anti-rabbit FITC-conjugated IgG (1:100) alone or its mixture with the donkey anti-goat Texas Red-conjugated IgG (1:100). Controls included substituting primary antibody with rabbit IgG and goat IgG. The nuclei were visualized by staining with hoechst 33258 for 10 min. Photomicrographs were taken under a confocal laser-scanning microscope (Leica, Germany).

Isolation of rat pancreatic islets

Pancreatic islets were isolated from male Sprague Dawley rats by collagenase digestion of the pancreas, then purified on discontinuous Ficoll DL-400 gradients as described previously [13].

Cell culture

INS-1 cells, a rat pancreatic islet cell line, were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 2 mM L-glutamine, 11.1 mM glucose, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM HEPES, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 10% fetal calf serum, and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 as described [14]. Cells were passaged weekly after trypsin-EDTA detachment. All studies were performed on INS-1 cells, passages 20–25.

HEK293 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated using the Trizol reagent. Reverse transcription was performed using the reverse transcription system according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR was conducted in 25 μL volume containing 2.5 μL of cDNA, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.2 μM each primer, 1.25 U Ampli Taq Polymerase and 1 μL of 800X diluted SYBR Green I stock using the Mx3000 Multiplex Quantitative PCR System (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The PCR program was: hold 95°C for 5 min; 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min. Melt curve analysis was from 60°C to 95°C at 0.2°C/second with Optics Ch1 On. mRNA expression was quantified using the comparative cross threshold (CT) method. The CT value of the housekeeping gene β-actin was subtracted from the CT value of the target gene to obtain ΔCT. The normalized fold changes of GOAT mRNA expression were expressed as 2−ΔΔCT where ΔΔCT equals to ΔCT sample – ΔCT control. PCR reactions were performed in duplicate and each experiment was repeated for 3–5 times. Primers used in this study were:

Rat GOAT Sense 5'-CGA GGC AGT GGA ACC GAA G-3'

Antisense 5'-GGC AAA AGT GTG GAT CAG ATA GTC-3'

Rat ghrelin Sense 5'-AAG CCC AGC AGA GAA AGG AAT C-3'

Antisense 5'-CAA CAT CGA AGG GAG CAT TGA AC-3'

Rat β-actin Sense 5'-GAG ACC TTC AAC ACC CCA GCC-3'

Anti sense 5'-TCG GGG CAT CGG AAC CGC TCA-3'

Western blot analysis

The pancreas, isolated islets or cultured INS-1 cells were quickly harvested, rinsed thoroughly with PBS, then homogenized on ice in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl, 15 mM EGTA, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100 supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail, pH 7.5). After centrifugation for 10 min at 4°C, the supernatant was used for Western blot analysis. Protein concentration was measured by Bradford's method. A total of 100 μg protein from each sample was loaded onto SDS-PAGE gel. Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. The membranes were incubated for 1h at room temperature with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in tris-buffered saline containing Tween 20, followed by incubation overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies. Specific reaction was detected using IRDye-conjugated second antibody for 1 h incubation and visualized using the Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE).

Construction of mouse GOAT promoter-luciferase expression vectors

The mouse GOAT promoter-luciferase hybrid genes were constructed as follows: series fragments of the 5'-flanking region of the mouse GOAT gene were amplified from mouse hepatic genomic DNA and subcloned into the promoterless pGL3-basic luciferase reporter vector MluI/XhoI clone site (-1999/-13, -1631/-13, -1097/-13, -657/-13, -165/-13, -81/-130, -44/-13). The PCR primers used were as follows:

Sense

-

–

1999 bp, 5'-CGA CGC GTG TCT GAA GAT AGT GAC AGT GTA CTC A-3';

-

–

1631 bp, 5'-CGA CGC GTA CAA GAT CAA AGA CAC CAT GAG ATG-3';

-

–

1097 bp, 5'- GTA CGC GTG GAA CTG AGA TCC GTG AGA GTA AG-3';

-

–

657 bp, 5'-CTG ACG CGT ATG TTG CTC TGG AAG AAAAGT C-3';

-

–

165 bp, 5'-GTA CGC GTG GGAAGC CAA CCT TTA CAT TGC- 3';

-

–

81 bp, 5'- CGA CGG TAC GGA GAG CCC AGT TGT GAC-3'. Antisense

-

–

13bp, 5'- CAC TCG AGG CCC ACT GTC CTT CCT AGA G-3'. -44/-13

5'GTA CGC GTA CCG CTT AGG GAC TCT AGG AAG GAC AGT GGG CCT CGA GTG-3'

5'CAC TCG AGG CCC ACT GTC CTT CCT AGA GTC CCT AAG CGG TAC GCG TAC-3'

Reporter assays

For transient transfection, cells were plated onto 24-well tissue culture plates at optimal densities and grown for 24h. Cells were then transfected with GOAT promoter-luciferase reporter gene constructs (500 ng) and an internal control pSV-β-galactosidase (25 ng) per well, using Lipofectamine reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were either harvested 48h later or grown overnight, then treated with chemicals for 16h. In parallel experiments, empty vector pGL3-basic was used as control. All cells were rinsed with PBS, lysed in 100 μl Passive Lysis Buffer. Cell lysates were analyzed for luciferase activity with the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System using a luminometer (Monolight 2010, Analytical Luminescence Laboratory, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. β-galactosidase activity was measured according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Statistical analysis

All values were expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical differences were evaluated by two-way ANOVA and Newman-Student-Keuls test. Comparisons between two groups involved use of the Student's t-test. P value < 0.05 denotes statistical significance.

Results

Expression of GOAT in pancreas and INS-1 cells

To determine whether GOAT is expressed in pancreatic tissues, immunofluorescent staining was used to localize GOAT in the murine pancreas. Expression of GOAT in the gastric epithelium was used as positive control. As shown in Fig. 1A, antibody recognizing GOAT demonstrated strong positive reactivity in rat pancreatic islets and gastric mucosal cells, while control antibody produced no signal. Double staining with insulin showed that the expression of GOAT in pancreas mainly exists in the islets (Fig. 1B). In rat or mouse pancreas, GOAT immunoreactivity was detected in the periphery of the islets, while insulin signal was visualized in a central distribution. No co-localization of GOAT and insulin was identified. To further confirm the expression of GOAT, we analyzed the expression of GOAT mRNA and protein in pancreatic islets. Expression of GOAT mRNA (Fig. 1C) and protein (Fig. 1D) at a level comparable to that in gastric mucosa was detected in rat pancreas, isolated islet cells and INS-1 cells, a rat pancreatic islet cell line. The expression of ghrelin mRNA was also detected in pancreas, isolated islet cells, and INS-1 cells (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Expression of GOAT in pancreas and INS-1 cells. (A) Detection of GOAT expression in rat pancreas. Expression of GOAT in the gastric epithelium was used as positive control. (B) Localization of GOAT in rat and mouse pancreas. Images depicting GOAT (green), insulin (red) and nuclei (blue) in pancreatic islet. Merged image illustrates colocalization of GOAT and insulin. (C) Expression of GOAT and ghrelin mRNA in rat tissues and INS-1cells was detected by PCR. β-actin was used as internal control. (D) Expression of GOAT protein in rat tissues and INS-1cells was detected by Western blot. β-actin was used as internal control.

Modulation of pancreatic GOAT expression by insulin

Although originally identified as an insulin secreting cell line, INS-1 cells have been demonstrated to express and release other hormones such as glucagon and neuropeptide Y in addition to insulin, suggesting its multi- hormonality [15, 16, 17]. Since abundance of GOAT was detected in INS-1 cells by both RT-PCR and Western blot (Fig. 1C, D), we next examined whether insulin could regulate GOAT expression using INS-1 cells as a model. Exposure of INS-1 cells to insulin inhibited GOAT mRNA and protein expression in a time-dependent manner. Inhibition of GOAT level occurred as early as 4h and persisted for up to 24h (Fig. 2A, B). Insulin treatment for 16h caused a concentration-dependent inhibition of GOAT mRNA and protein expression (Fig. 2C, D), with maximal inhibition at 1000 nM insulin. Inhibition of the PI3 kinase/Akt pathway by wortmannin treatment confirmed that the inhibitory effect of insulin on GOAT expression is mediated by the classical insulin receptor signaling pathway (Fig. 2E). As the endogenous insulin secreted from INS-1 cells cultured for 20h was detected in culture supernatant at a level of 0.3 nM, the observed inhibition of GOAT expression by insulin was considered to be mainly the result of exogenously administrated insulin.

Fig. 2.

Modulation of GOAT expression by insulin in INS-1 cells. (A&B) Time course effect of 100 nM insulin treatment for the indicated time periods on GOAT mRNA (A) and protein (B) levels in INS-1 cells. (C&D) Dose-dependent effect of insulin treatment with indicated concentrations for 16 h on GOAT mRNA (C) and protein (D) levels in INS-1 cells. (E) Attenuation of insulin-induced inhibition of GOAT expression by wortmannin treatment (1μM). Representative Western blots of p-Akt and p-S6 were shown in panel E. β-actin was used as internal control. Relative GOAT mRNA levels were normalized with respect to the levels of untreated cells. Data are means±SEM from 4 separate experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 versus untreated cells. ##P<0.01 versus insulin-treated alone.

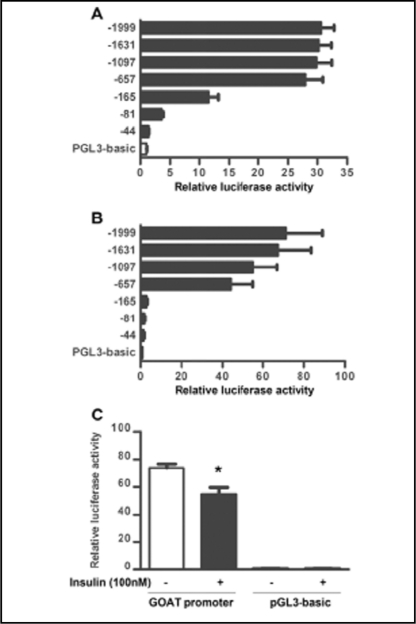

To determine whether insulin inhibits the expression of GOAT by regulating transcription, we examined the promoter activity of a variety of deletion constructs containing different lengths of the upstream GOAT gene fused to the reporter luciferase gene. As shown in Figure 3A and B, the GOAT promoter segments from -1999, -1631, -1097 and -657 bp upstream of the transcriptional initiation site showed promoter activity when transfected into HEK293 cells (without endogenous GOAT and ghrelin) and INS-1 cells. Upon exposure to insulin (100 nM), promoter activity was reduced by 30% (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Modulation of GOAT transcription by insulin in INS-1 cells. Relative luciferase activity in HEK 293 cells (A) and INS- 1 cells (B) in transient transfection assays using the series of plasmid constructs. (C) Inhibition of GOAT promoter activity (-1999 bp upstream of the transcriptional initiation site) by insulin (100 nM) in INS-1 cells. The basal promoter activity of each test plasmid is indicated as luciferase activity normalized by each internal control activity (pSV-β-galactosidase). Relative luciferase activity was normalized with respect to the activity of PGL3-basic in untreated cells. Data are mean±SEM of 3 independent duplicated experiments. *P<0.05 versus insulin untreated cells transfected with GOAT promoter.

Role of mTOR signaling in inhibition of pancreatic GOAT expression by insulin

Since gastric mTOR signaling has been demonstrated to regulate GOAT expression and insulin may activate mTOR signaling [18, 19], we next examined whether mTOR signaling is involved in the inhibition of pancreatic GOAT expression by insulin. As shown in Fig. 4, insulin treatment (100 nM) significantly increased phosphorylation of Akt (Ser473), TSC2 (Thr1462), mTOR (Ser2448) and S6 ribosomal protein (Ser235/236), the downstream target of mTOR, in INS-1 cells. Rapamycin, an inhibitor of mTOR signaling, dose- and time-dependently increased GOAT expression in INS-1 cells (Fig. 5A, B). Consistent with these in vitro studies, intraperitoneal administration of rapamycin (1 mg/kg body weight/day for 7 days) significantly increased expression of GOAT mRNA in pancreas derived from C57 mice (Fig. 5C). Conversely, exposure to leucine (0.45g/kg body weight/day for 7 days), an activator of mTOR [20], significantly inhibited expression of GOAT mRNA (Fig. 5C). To further confirm the effect of mTOR on GOAT expression, we inhibited mTOR activity by overexpression of its negative regulators, tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) gene TSC1 and TSC2. As shown in Fig. 5D, overexpression of TSC1 or TSC2 significantly increased GOAT expression, and both TSC1 and TSC2 function to inhibit mTOR signaling.

Fig. 4.

Activation of mTOR signaling by insulin in INS-1 cells. Cells were incubated with 100 nM insulin for the indicated time and whole-cell lysates were used for Western blotting. Total and phosphorylation form of Akt (Ser473), TSC2 (Thr1462), mTOR (Ser2448) and S6 ribosomal protein, the downstream target of mTOR were detected. The eIF4E was used as internal control.

Fig. 5.

Modulation of GOAT expression by mTOR signaling inhibition. (A) Time course effect of 25 nM rapamycin, the mTOR signaling inhibitor, on GOAT mRNA and protein levels in INS-1 cells. (B) Dose-response of rapamycin treatment with indicated concentrations for 16 hours on GOAT mRNA and protein levels in INS-1 cells. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 versus untreated cells. (C) Results of quantitative PCR analysis of pancreatic GOAT mRNA levels in mice that received intraperitoneal injection of DMSO, rapamycin (1 mg/kg body weight/day for 7 days) or L-leucine (0.45g/kg body weight/day for 7 days), an activator of mTOR. β- actin was used as internal control. Relative GOAT mRNA levels were normalized with respect to the levels of DMSO-treated mice. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 versus DMSO-treated mice. (D) Upregulation of GOAT mRNA and protein levels by overexpression of TSC1 and TSC2 in INS-1 cells. INS-1 cells were transfected with one of the following plasmids: pcDNA3.1, human TSC1, rat TSC2. **P<0.01 versus cells transfected with pcDNA3 alone. (E) Activation of GOAT promoter activity by rapamycin in INS-1 cells. Data are mean±SEM of 3 independent duplicated experiments. **P<0.01 versus rapamycin untreated cells transfected with GOAT promoter. (F) Activation of GOAT promoter activity by overexpression of TSC1 and TSC2 in INS-1 cells. INS-1 cells were co-transfected with GOAT promoter-luciferase plasmid and one of the following plasmids: pcDNA3.1, human TSC1, rat TSC2. **P<0.01 versus cells co-transfected with pcDNA3 and GOAT promoter. The basal promoter activity of each test plasmid is indicated as luciferase activity normalized by each internal control activity (pSV-β-galactosidase). Relative luciferase activity was normalized with respect to the activity of PGL3-basic in untreated cells. The lower panels of western blot confirmed the inhibition of mTOR activity by rapamycin or TSC1 and TSC2 transfection.

In order to determine whether mTOR signaling regulates GOAT transcription, we assayed GOAT promoter activity. As shown in Fig. 5E and F, rapamycin or overexpression of TSC1 or TSC2 significantly increased luciferase activity in INS-1 cells transfected with GOAT promoter-luciferase plasmid relative to controls, suggesting that down-regulation of mTOR signaling leads to an increase in GOAT promoter activity.

The inhibition of GOAT expression and GOAT promoter activity induced by insulin could be restored by pretreatment of INS-1 cells with rapamycin or overexpression of TSC1 or TSC2 (Fig. 6A–C).

Fig. 6.

Role of mTOR signaling in inhibition of GOAT expression by insulin in INS-1 cells. (A) Attenuation of insulin-induced inhibition of GOAT expression by rapamycin treatment (25nM). β-actin was used as internal control. Relative GOAT mRNA levels were normalized with respect to levels of untreated cells. (B) Attenuation of insulin-induced inhibition of GOAT promoter activity by rapamycin treatment. The basal promoter activity is indicated as luciferase activity normalized by internal control activity (pSV-β-galactosidase). Relative luciferase activity was normalized with respect to the activity of PGL3-basic in untreated cells. (C) Attenuation of insulin-induced inhibition of GOAT expression by overexpression of TSC1 and TSC2 in INS-1 cells. β-actin was used as internal control. Relative GOAT mRNA levels were normalized with respect to levels of cells transfected with pcDNA3.1 alone. Data are mean±SEM of 3 independent duplicated experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 versus untreated cells. ##P<0.01 versus insulin-treated alone. Representative Western blots of p-Akt, p-mTOR and p-S6 were shown. eIF4E was used as the internal control.

Discussion

The current study has demonstrated that GOAT is expressed in pancreatic islet cells and that its expression is modulated by insulin. This conclusion is supported by the following observations: 1) both GOAT mRNA and immunoreactivity are detected in the pancreas islets and INS-1 cells, a pancreatic islet cell line; 2) insulin inhibits the expression of GOAT mRNA in a dose and time-dependent manner; 3) GOAT promoter activity is inhibited by insulin; 4) insulin activates mTOR signaling and Akt phosphorylation in INS-1 cells; 5) blocking mTOR signaling by either rapamycin or overexpression of TSC1 or TSC2 increases the transcription and translation of GOAT; 6) pretreatment of INS-1 cells with rapamycin or overexpression of TSC1 or TSC2 blocks the inhibitory effect of insulin on GOAT expression; 7) rapamycin significantly increases, while leucine inhibits, the expression of GOAT mRNA in pancreas derived from C57 mice.

Although GOAT mRNA has been detected in the human stomach and pancreas, its protein expression in pancreas has not been reported. Our study demonstrates the presence of both GOAT mRNA and immunoreactivity in both mouse and rat pancreatic islets. The gastric GOAT gene is conserved across vertebrates from zebrafish, to mouse, rat, and human [11, 12]. Even though GOAT shares structural similarities with other members of the MBOAT family of acyl transferases, GOAT is the only enzyme able to catalyze the octanoylation of ghrelin.

The conserved catalytic histidine residue in GOAT is critical for its enzymatic activity. Substitution of histidine 338 with alanine (H338A) abolishes enzymatic activity [12]. Murine GOAT covalently binds octanoyl residues to Ser3 of ghrelin. Silencing of GOAT gene in TT cells, a cell line derived from thyroid carcinoma in which both GOAT and ghrelin have been detected, significantly decreases the production of acyl ghrelin. GOAT gene knockout mice lack octanoylated ghrelin, consistent with the concept that GOAT is the acyltransferase required for the n-octanoylation of ghrelin. The substrate that GOAT uses to acylate ghrelin is not limited to octanoate and may include other fatty acids ranging from acetate to tetradecanoic acid, although peak intensities for acyl-modified forms of ghrelin correspond to C7 to C12 molecules [11].

While a number of recent observations suggest that ghrelin may have a function in glucose homeostasis, a definite role has not yet been defined. Ghrelin has been variously reported to either suppress glucose-induced insulin release or stimulate insulin secretion from pancreatic islet cells [21, 22, 23, 24]. Deletion of ghrelin or GHSR1a gene alters glucose metabolism by affecting the survival and function of β-cells [25, 26]. A recent study by Kirchner et al suggests that expression of GOAT is tightly related to the lipid consumption [27], and administration of leptin has been found to significantly increase the expression of gastric GOAT mRNA in fasted rats [28]. These observations indicate that expression of GOAT in the gastric mucosa may be linked to energy supply and perhaps to organismal energy balance.

Even though ghrelin is mainly secreted from gastric X/A like endocrine cells, the expression of ghrelin in pancreatic islet cells suggests that pancreatic ghrelin may also regulate islet function. The previous identity of ghrelin expressing cells and GHSR1a in pancreatic islet cells indicated that pancreatic ghrelin might affect islet cells by paracrine and/or autocrine mechanisms to regulate insulin secretion [29, 30]. Our study extends this observation by demonstrating that insulin might regulate the production of acyl ghrelin by affecting the expression of GOAT. However, it is worth noting that controversy exists about the expression of ghrelin in pancreatic islets. While ghrelin is expressed abundantly in fetal pancreatic islets, expression decreases significantly in the adult pancreas. In pancreatic islet cell lines, acyl ghrelin has been reported to be either detectable [31] or undetectable [12]. Culture condition may contribute to the variability in the production of acyl ghrelin as demonstrated by the finding that octanoate is necessary for cultured TT cells to secret acyl ghrelin [11]. We found that GOAT is abundant in lNS-1 cells. Whether GOAT may exert other function in addition to catalyze the acylation of ghrelin remains to be explored.

Insulin signaling involves a wide variety of genes such as IRS, Akt, Pten, Pdk1, and mTOR [32]. mTOR is a highly conserved serine-threonine kinase [33]. mTOR has been reported to serve as an intracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) sensor [34], linking cellular energy levels to the cellular growth. Emerging evidence also indicates that mTOR is critical for the regulation of energy balance by coordinating cellular energy levels with the status of overall energy supply and expenditure [35].

mTOR participates in the regulation of glucose metabolism through mechanisms which are target tissue-specific. In the pancreas, deletion of TSC1, an upstream inhibitor of mTOR signaling, results in enlarged β-cell size and increased pancreatic insulin content driven by high mTOR activity in pancreatic islet cells [36]. The current study demonstrates the presence of mTOR signaling in pancreatic islet cells and may also play a role in the regulation of GOAT expression.

Two pathways for mTOR signaling have been described: a rapamycin dependent pathway in which TSC1/TSC2 heterodimer negatively regulates mTOR signaling and a rapamycin independent pathway. Our study demonstrates that rapamycin dependent mTOR signaling pathway is involved in the regulation of GOAT expression. Furthermore, our study suggests that mTOR is critical for the inhibitory effect of insulin on GOAT transcription and translation in pancreatic islet cells. Four observations support this concept: 1) insulin activates mTOR signaling in INS-1 islet cells; 2) blocking mTOR signaling by either rapamycin, a well characterized mTOR inhibitor, or overexpression of TSC1 or TSC2 increases GOAT expression; 3) blunting mTOR signaling by rapamycin or overexpression of TSC1 or TSC2 reverses the inhibition of GOAT expression which are induced by insulin; 4) inhibition of mTOR signaling by rapamycin stimulates, while activation of mTOR signaling by leucine inhibits the expression of GOAT mRNA in mouse pancreas. Analysis of GOAT promoter activity shows that insulin inhibits GOAT expression by reducing transcription of the GOAT gene. The regulatory site specific for insulin action is located between -1999kb and -1631kb within the GOAT promoter.

Distinct signaling pathways have been demonstrated to either increase or reduce the activity of TSC2, dependent on phosphorylation sites. Phosphorylation of Thr1462 amino acid of TSC2 by Akt down-regulates the activity of TSC2 [37], while AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) enhances the function of TSC2 by phosphorylating its Thr1227/Ser1345 amino acids [38]. Consistent with this concept, our study demonstrates that insulin inhibits the functional activity of TSC2 by Akt signaling, leading to increased mTOR activity in pancreatic islet cells. Insulin inhibits the expression of GOAT likely through decreasing the activity of TSC2.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that GOAT is present in murine pancreatic islet cells and that insulin inhibits the expression of GOAT by the mediation of mTOR signaling. Based on these findings we propose that insulin may function to decrease the production of acyl ghrelin via reducing the expression of GOAT, providing a regulatory mechanism for insulin secretion.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to professor Kunliang Guan (UCSD) for providing human mTOR, human TSC1 and rat TSC2 plasmids. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81030012, 30890043, 30971434, 30871194, 30821001, 30700376 and 30971085), the Major National Basic Research Program of P. R. China (No. 2010CB912504), the '985' Program at Peking University (985-2-097-121), and National Institute of Health grant RO1DK043225.

References

- 1.Kojima M, Hosoda H, Date Y, Nakazato M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K. Ghrelin is a growth-hormone-releasing acylated peptide from stomach. Nature. 1999;402:656–660. doi: 10.1038/45230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kojima M, Kangawa K. Ghrelin: Structure and function. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:495–522. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang W, Chen M, Chen X, Segura BJ, Mulholland MW. Inhibition of pancreatic protein secretion by ghrelin in the rat. J Physiol. 2001;537:231–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0231k.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang W, Hu Y, Lin TR, Fan Y, Mulholland MW. Stimulation of neurogenesis in rat nucleus of the solitary tract by ghrelin. Peptides. 2005;26:2280–2288. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang W, Lin TR, Hu Y, Fan Y, Zhao L, Stuenkel EL, Mulholland MW. Ghrelin stimulates neurogenesis in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. J Physiol. 2004;559:729–737. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.064121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang W, Zhao L, Lin TR, Chai B, Fan Y, Gantz I, Mulholland MW. Inhibition of adipogenesis by ghrelin. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:2484–2491. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-09-0657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang W, Zhao L, Mulholland MW. Ghrelin stimulates myocyte development. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2007;20:659–664. doi: 10.1159/000107549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun Y, Asnicar M, Smith RG. Central and peripheral roles of ghrelin on glucose homeostasis. Neuroendocrinology. 2007;86:215–228. doi: 10.1159/000109094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang W, Chai B, Li JY, Wang H, Mulholland MW. Effect of des-acyl ghrelin on adiposity and glucose metabolism. Endocrinology. 2008;149:4710–4716. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prado CL, Pugh-Bernard AE, Elghazi L, Sosa-Pineda B, Sussel L. Ghrelin cells replace insulin-producing beta cells in two mouse models of pancreas development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2924–2929. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308604100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gutierrez JA, Solenberg PJ, Perkins DR, Willency JA, Knierman MD, Jin Z, Witcher DR, Luo S, Onyia JE, Hale JE. Ghrelin octanoylation mediated by an orphan lipid transferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:6320–6325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800708105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang J, Brown MS, Liang G, Grishin NV, Goldstein JL. Identification of the acyltransferase that octanoylates ghrelin, an appetite-stimulating peptide hormone. Cell. 2008;132:387–396. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gotoh M, Maki T, Satomi S, Porter J, Bonner-Weir S, O'Hara CJ, Monaco AP. Reproducible high yield of rat islets by stationary in vitro digestion following pancreatic ductal or portal venous collagenase injection. Transplantation. 1987;43:725–730. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198705000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janjic D, Asfari M. Effects of cytokines on rat insulinoma ins-1 cells. J Endocrinol. 1992;132:67–76. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1320067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waeber G, Thompson N, Waeber B, Brunner HR, Nicod P, Grouzmann E. Neuropeptide y expression and regulation in a differentiated rat insulin-secreting cell line. Endocrinology. 1993;133:1061–1067. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.3.8396008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bollheimer LC, Wrede CE, Rockmann F, Ottinger I, Scholmerich J, Buettner R. Glucagon production of the rat insulinoma cell line ins-1-a quantitative comparison with primary rat pancreatic islets. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;330:327–332. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.01.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arumugam R, Fleenor D, Freemark M. Lactogenic and somatogenic hormones regulate the expression of neuropeptide y and cocaine- and amphetamine- regulated transcript in rat insulinoma (ins-1) cells: Interactions with glucose and glucocorticoids. Endocrinology. 2007;148:258–267. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu G, Li Y, An W, Li S, Guan Y, Wang N, Tang C, Wang X, Zhu Y, Li X, Mulholland MW, Zhang W. Gastric mammalian target of rapamycin signaling regulates ghrelin production and food intake. Endocrinology. 2009;150:3637–3644. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inoki K, Li Y, Zhu T, Wu J, Guan KL. Tsc2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by akt and suppresses mtor signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:648–657. doi: 10.1038/ncb839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu G, Kwon G, Cruz WS, Marshall CA, McDaniel ML. Metabolic regulation by leucine of translation initiation through the mtor-signaling pathway by pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes. 2001;50:353–360. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adeghate E, Ponery AS. Ghrelin stimulates insulin secretion from the pancreas of normal and diabetic rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 2002;14:555–560. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2002.00811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Date Y, Nakazato M, Hashiguchi S, Dezaki K, Mondal MS, Hosoda H, Kojima M, Kangawa K, Arima T, Matsuo H, Yada T, Matsukura S. Ghrelin is present in pancreatic alpha-cells of humans and rats and stimulates insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2002;51:124–129. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.1.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Egido EM, Rodriguez-Gallardo J, Silvestre RA, Marco J. Inhibitory effect of ghrelin on insulin and pancreatic somatostatin secretion. Eur J Endocrinol. 2002;146:241–244. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1460241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dezaki K, Hosoda H, Kakei M, Hashiguchi S, Watanabe M, Kangawa K, Yada T. Endogenous ghrelin in pancreatic islets restricts insulin release by attenuating ca2+ signaling in beta-cells: Implication in the glycemic control in rodents. Diabetes. 2004;53:3142–3151. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.12.3142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zigman JM, Nakano Y, Coppari R, Balthasar N, Marcus JN, Lee CE, Jones JE, Deysher AE, Waxman AR, White RD, Williams TD, Lachey JL, Seeley RJ, Lowell BB, Elmquist JK. Mice lacking ghrelin receptors resist the development of diet-induced obesity. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3564–3572. doi: 10.1172/JCI26002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun Y, Asnicar M, Saha PK, Chan L, Smith RG. Ablation of ghrelin improves the diabetic but not obese phenotype of ob/ob mice. Cell Metab. 2006;3:379–386. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirchner H, Gutierrez JA, Solenberg PJ, Pfluger PT, Czyzyk TA, Willency JA, Schurmann A, Joost HG, Jandacek RJ, Hale JE, Heiman ML, Tschop MH. Goat links dietary lipids with the endocrine control of energy balance. Nat Med. 2009;15:741–745. doi: 10.1038/nm.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gonzalez CR, Vazquez MJ, Lopez M, Dieguez C. Influence of chronic undernutrition and leptin on goat mrna levels in rat stomach mucosa. J Mol Endocrinol. 2008;41:415–421. doi: 10.1677/JME-08-0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Volante M, Allia E, Gugliotta P, Funaro A, Broglio F, Deghenghi R, Muccioli G, Ghigo E, Papotti M. Expression of ghrelin and of the gh secretagogue receptor by pancreatic islet cells and related endocrine tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1300–1308. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.3.8279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kageyama H, Funahashi H, Hirayama M, Takenoya F, Kita T, Kato S, Sakurai J, Lee EY, Inoue S, Date Y, Nakazato M, Kangawa K, Shioda S. Morphological analysis of ghrelin and its receptor distribution in the rat pancreas. Regul Pept. 2005;126:67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2004.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakashima K, Kanda Y, Hirokawa Y, Kawasaki F, Matsuki M, Kaku K. Min6 is not a pure beta cell line but a mixed cell line with other pancreatic endocrine hormones. Endocr J. 2009;56:45–53. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k08e-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takano A, Usui I, Haruta T, Kawahara J, Uno T, Iwata M, Kobayashi M. Mammalian target of rapamycin pathway regulates insulin signaling via subcellular redistribution of insulin receptor substrate 1 and integrates nutritional signals and metabolic signals of insulin. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:5050–5062. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.15.5050-5062.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brunn GJ, Fadden P, Haystead TA, Lawrence JC., Jr The mammalian target of rapamycin phosphorylates sites having a (ser/thr)-pro motif and is activated by antibodies to a region near its cooh terminus. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32547–32550. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dennis PB, Jaeschke A, Saitoh M, Fowler B, Kozma SC, Thomas G. Mammalian tor: A homeostatic atp sensor. Science. 2001;294:1102–1105. doi: 10.1126/science.1063518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cao Y, Kamioka Y, Yokoi N, Kobayashi T, Hino O, Onodera M, Mochizuki N, Nakae J. Interaction of foxo1 and tsc2 induces insulin resistance through activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin/p70 s6k pathway. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:40242–40251. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608116200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mori H, Inoki K, Opland D, Muenzberg H, Villanueva EC, Faouzi M, Ikenoue T, Kwiatkowski D, Macdougald OA, Myers Jr MG, Guan KL. Critical roles for the tsc-mtor pathway in beta-cell function. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297:1013–1022. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00262.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marin TM, Clemente CF, Santos AM, Picardi PK, Pascoal VD, Lopes-Cendes Saad MJ, Franchini KG. Shp2 negatively regulates growth in cardiomyocytes by controlling focal adhesion kinase/src and mtor pathways. Circ Res. 2008;103:813–824. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.179754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Inoki K, Ouyang H, Zhu T, Lindvall C, Wang Y, Zhang X, Yang Q, Bennett C, Harada Y, Stankunas K, Wang CY, He X, MacDougald OA, You M, Williams BO, Guan KL. Tsc2 integrates wnt and energy signals via a coordinated phosphorylation by ampk and gsk3 to regulate cell growth. Cell. 2006;126:955–968. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]