Abstract

Background/Aims: The role of H. pylori in the pathogenesis of ulcer disease in cirrhotic patients is poorly defined. Therefore, we sought to investigate the prevalence of H. pylori infection and the occurrence of gastroduode-nal lesions in patients with liver cirrhosis. Methods and Patients: Seroprevalence of H. pylori was tested in 110 patients with liver cirrhosis and 44 asymptomatic patients with chronic hepatitis without cirrhosis using an anti-H. pylori-IgG-ELISA. Cirrhotic patients underwent upper intestinal endoscopy for macroscopic and histological evaluation of gastric mucosa, and for the detection of mucosal colonisation of H. pylori using Giemsa staining and urease test. Results: There was no significant difference between the H. pylori seroprevalence in patients with liver cirrhosis (76/110; 69%) and patients with chronic viral hepatitis (27/44, 63%, p=0.465). Gastric mucosal colonization with H. pylori in cirrhotic patients was significantly lower than the serologically determined H. pylori prevalence (45% vs. 69%, p=0.001). Etiology of liver cirrhosis did not influence the prevalence of H. pylori infection. 8 of 110 cirrhotic patients had gastric ulcers and 10 had duodenal ulcers. 61% of cirrhotic patients with peptic ulcers were asymptomatic. H. pylori was histologically identified in 61% of gastroduodenal ulcers, and 47% of gastroduodenal erosions. Conclusions: Patients with liver cirrhosis have a high prevalence of gastroduodenal ulcers. The lack of a firm association between H. pylori prevalence and ulcer frequency in cirrhotic patients argues against a pivotal role of H. pylori in the etiology of ulcers in cirrhotic patients.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, liver cirrhosis, hepatitis, gastroduodenal ulcers

Introduction

H. pylori, is a non-invasive, gram-negative bacterium which colonizes gastric mucosa is the principle cause of type B gastritis and peptic ulcer disease, and is also associated with gastric cancer and MALT lymphoma [1, 2]. Although several virulence factors of H. pylori have been identified (e.g. vacuolating cytotoxin, urease, motility) the precise mechanisms whereby H. pylori causes mucosal damage have yet to be defined [3, 4]. The prevalence of peptic ulcer disease in cirrhotic patients has been reported to be approximately 5-20% (based on endoscopy screening) compared to 2-4% in the general population [5-9]. The reasons of the increased ulcer rate in cirrhotic patients are unknown. Oxidative stress causes gastric tissue damage in cirrhotic patients and may be one component in causing gastric lesions and hemorrhage [10]. H. pylori plays a pivotal role in the etiology of peptic ulcer disease in the normal population [1, 11], but little is known on its pathophysiologic role in cirrhotic patients and its association with ulcer formation in cirrhotics [6, 8, 12-14]. Eradication of H. pylori in patients with liver cirrhosis and duodenal ulcers did not effectively reduce the recurrence of ulcers [9, 15]. The frequency of H. pylori infection in cirrhosis has been reported to vary between 10% to 49% [13, 16-18] and the reported values are not different from those reported in patients without cirrhosis [19]. The reason for this considerable variation in H. pylori prevalence in cirrhosis is unknown, but differences in the severity of hepatic cirrhosis and/or complicating congestive gastropathy or inaccuracy of the H. pylori detection methods could play a role.

These factors have not been systematically investigated in previous studies about the H. pylori and ulcer prevalence in liver cirrhosis.

The present study investigated the prevalence of H. pylori in patients with liver cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis using anti-H. pylori IgG serol-ogy and invasive detection of gastric mucosal colonization by Giemsa stain and urease test. In addition, the H. pylori status was correlated with the occurrence of gastroduodenal lesions. Finally, the influence of the etiology and severity of liver cirrhosis on the presence of H. pylori and endoscopic lesions was analyzed.

Patients and methods

Patients

In this study 182 patients with liver cirrhosis, who had been admitted to the Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Endocrinology, Medical School of Hannover, for evaluation of the indication for liver transplantation or therapy optimization, were assessed for study inclusion. Inclusion criteria were cirrhotic patients between the age of 18 and 80 years old. Informed consent was obtained from each patient, according to the revised version of the Declaration of Helsinki. The diagnosis of cirrhosis in each case was confirmed by a combination of ultrasound, liver function parameters (cholinesterase, prothrombin time and serum albumin), and presence of esophageal or fundal varices and by a liver histology in ambiguous cases. Patients with primary or secondary hepatic malignancy, those with fulminant hepatic failure, with a history of gastric surgery, and acute variceal bleeding were excluded from this study. In addition, not included were patients with intake of antibiotics, antacids, H2-antagonists, proton pump inhibitors, aspirin, or anti-inflammatory drugs during the four weeks before upper intestinoscopy were excluded. The severity of liver cirrhosis was assessed using the Child-Pugh-Classification. According to this scoring system, patients were classified in class A, if the score was 5 to 6, in class B if the score is 7-10 and class C if the score is higher than 11.

110 patients (67 men, 43 women; mean age 50+13 years) who met the inclusion criteria with liver cirrhosis were evaluated. 33 of 110 patients were smokers. The causes of liver cirrhosis were as follows: 42 patients had alcoholic, 14 patients chronic hepatitis B, 18 patients chronic hepatitis C, 12 patients primary biliary cirrhosis, 7 patients primary sclerosing cholangitis and 17 patients had other causes of liver cirrhosis (1 Wilson∼s disease, 5 autoimmune hepatitis, 1 Alpha-1-Antitrypsin deficiency, 1 Budd-Chiari, and 9 cryptogenic). 25 patients were classified as Child A, 49 patients had Child B, and 36 patients had Child C cirrhosis. All patients had undergone an upper intestinoscopy during their stay in hospital.

For comparison, we also investigated the H. pylori serology of 44 patients (22 male, 22 female; mean age 46+17 years, 10 smokers) with histologically confirmed chronic hepatitis but no evidence of cirrhosis (24 patients with hepatitis C, 14 patients with hepatitis B, 6 patients with autoimmune hepatitis), who had been treated during the same time period at the Medical School of Hannover.

Endoscopy

All cirrhotic patients had undergone an endoscopic examination of their gastrointestinal tract. Gastroduodenal lesions were classified into gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer, gastroduodenal erosions, gastritis, congestive gastropathy or no abnormal findings. Active ulcer was defined as a fibrin covered mucosal lesion with a minimal size of 5 mm. Presence of congestive gastropathy was evaluated according to McCor-mack∼s classification [20] and presence of fundal and/or esophageal varices was graded (0-4) using classification of Paquet [21]. At each endoscopy three biopsy specimens were taken with sterilised biopsy forceps from antral mu-cosa 2 cm proximal to the pylorus, and two biopsy specimens from the greater curvature of the corpus. In case of gastric lesions additional biopsies were taken from these sites as described previously [3]. Two biopsies from the antrum and body were fixed in 10% formalin for histopathology (Giemsa staining). The remaining specimen from the antrum was used for the rapid urease analysis (CLO-test, Delta West Ltd, Australia). All endoscopies were performed by endoscopists with experience ranging from 3 to 8 years.

H. pylori serology

All patients were screened for H. pylori prevalence using a commercial ELISA kit (GAP-IgG-Test, Bio-Rad Laboratories GmbH, Munich, Germany). This test has been previously validated in 277 patients with upper gastrointestinal symptoms giving the following characteristics: sensitivity 99.4%, specificity 93.5%, accuracy 97.4% (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

At the day of admission the blood was drawn from the studied patients. The ELISA was performed as recommended by the manufacturer. Diluted specimen was added to the microtiter plates, which were incubated at 25°C for 60 min, subsequently. After washing, horseradish peroxidase-IgG conjugate reagent was added followed by an incubation for 30 min at 25°C. Then tetramethylbenxidine (TMB) enzyme substrate reagent was added and incubated in the dark for 10 min at 25°C. After terminating the reaction, absorbance was measured using a 450 nm filter with a 615-620 nm filter as reference. H. pylori serology test results were defined as follows: H pylori positive >20 U/ml, H pylori negative <12.5 U/ml, equivocal 12.5-20 U/ml. Patients with equivocal test results were excluded.

Histopathology

For histological examinations, formalin fixed biopsy samples were embedded in paraffin and sections (4 μm) were stained with haematoxylin and eosin and Giemsa. Each biopsy specimen was assessed for the presence, type, density and localisation of the inflammatory infiltrate. Gastritis was classified according to the Sidney classification as described previously. Presence of H. pylori was identified by Giemsa stain [22].

Urease test (CLO-test)

In addition, we used the CLO-test (Delta West, Bently, Australien) for detection of H. pylori. This detection method is based on a colouring, which is due to bacterial urease activity. The presence of H. pylori was indicated by a red colouring within 24 hours.

Stastistics

Statistical analysis was made with the SAS-statistics system (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Chi-square test with Yates ∼ correction was used to analyze the relation between different variables. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

H. pylori seroprevalence

The seroprevalence of H. pylori was not significantly different between patients with liver cirrhosis and hepatitis without cirrhosis (69%; 76/110 versus 63%, 27/44; p=0.47; Table 1). H. pylori prevalence did not correlate with smoking habits or gender in any of the study groups.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and seroprevalence of H. pylori in cirrhotic patients and chronic hepatitis patients

| Cirrhotic | Chronic hepatitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 110 | 44 |

| Male | 67 | 22 |

| Female | 43 | 22 |

| Mean-age (years) | 50±13 | 46±17 |

| HP positive | 76(69%) | 27(63%) |

| HP negative | 34(31%) | 17(37%) |

Comparison between H. pylori seroprevalence and gastric mucosal H. pylori colonization

Seroprevalence of H. pylori in cirrhotic patients (69%) was compared with gastric mucosal H. pylori colonization using Giemsa stain and rapid urease test. In 95% (105/110) of cirrhotic patients the rapid urease test and Giemsa staining gave concordant results, while in 5 patients either Giemsa stain (3 patients) alone or urease test (2 patients) alone were positive. Using both a positive Giemsa stain and a positive urease test as evidence of H. pylori infection 50 of 110 (45%) cirrhotic patients were classified H. pylori positive. Considering patients infected by either a positive urease test or direct appearance of bacteria in Giemsa stains, H. pylori prevalence amounted to 50% (55 of 110).

Influence of the severity and etiology of cirrhosis on H. pylori prevalence

Cirrhotic patients classified as Child C had significantly higher H. pylori seroprevalence rate (89%) than patients with Child A (48%; p=0.001) and Child B (65%; p=0.021). But the H. pylori seroprevalence between Child A and Child B did not reach statistical significance. In contrast, gastric mucosal colonization with H. pylori was not significantly related to the Child classification. The etiology of liver cirrhosis did not significantly influence the seroprevalence of H. pylori: 79% (33/42) alcoholic, 79% (11/14) hepatitis B, 67% (12/18) hepatitis C, 67% (8/12) primary biliary cirrhosis, 57% (4/7) primary sclerosing cholangitis, and 47% (8/17) others.

Endoscopic findings and H. pylori prevalence

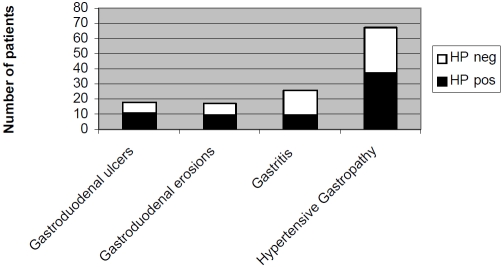

The endoscopic findings in 110 patients with liver cirrhosis are summarized in Figure 1. Eighteen patients had gastroduodenal ulcers (8 gastric ulcers and 10 duodenal ulcers). Only 39% (7/18) of cirrhotic patients with gastroduodenal ulcers had dyspeptic symptoms. Seventy-eight percent of patients with gastroduodenal ulcers had evidence of portal hypertension with congestive gastropathy or oesophageal or fundic varices. Seven percent of cirrhotic patients had normal endoscopic findings. H. pylori was his-tologically identified in 61% (11/18) of gastroduodenal ulcers, in 53% (9/17) of gastroduodenal erosions and in 35% (9/26) of gastritis. In 55% (37/67) of cirrhotic patients with congestive gastropathy gastric mucosa was colonized by H. pylori. None of the patients with normal gastric mucosal endoscopic appearance were colonized by H. pylori.

Figure 1.

shows the number of cirrhotic patients with pathologic endoscopic findings (multiple entries per patient possible). In addition, for each pathologic endoscopic finding the H. pylori status (HP neg = H. pylori negative; HP pos = H. pylori positive) detected by histology (Giemsa stain) is given.

The magnitude of H. pylori IgG serology did not correlate with the presence (34.7 + 25.0 IU/ml) or absence (34.0 + 21.9 IU/ml) of peptic ulcer disease.

Discussion

Anti-H. pylori IgG serology has been shown to be an accurate method for prediction of the H. pylori status in the normal population [23]. The present study shows that patients with liver cirrhosis have a high seroprevalence of H. pylori (69%) being comparable with data reported by Wu et al. in compensated (62%) and decompen-sated (75%) cirrhotic patients [13]. However, our study also demonstrates that gastric mucosal detection of H. pylori by Giemsa stain and urease test results in a considerably lower H. pylori prevalence in cirrhotic patients (45%). A disproportionally high seroprevalence of H. pylori has also been reported in a previous study by Nardone et al comparing serological and his-tological methods in cirrhotic patients [24]. The reason for this discrepancy between the sero-logical and histological H. pylori prevalence is unknown. In our study this discrepancy was more pronounced in patients with advanced liver disease (Child C) which could reflect a more intense immune response in such patients. Previous reports on H. pylori infection in cirrhotic patients which employed histological detection methods showed prevalence rates 19% to 49% which are in the range of the present study [13, 16-18]. The higher seroprevalence rate in cirrhotics could result from a previous H. pylori colonization which has been eliminated but which is still showing a serologic immune response. Liver cirrhosis is characterized by immunological disturbances and by hyper-globulinemia which could affect the serological detection method for H. pylori. Thus, the increased seroprevalence in cirrhotic patients could be due to an impaired specificity of the anti-H. pylori-ELISA. This might, at least partly, depend on cross reaction with other bacterial species that share antigens with H. pylori or it may be related to non-specific immune activation secondary to porto-systemic shunting.

In the present study a high frequency of gastroduodenal ulcers (16.4%; 18/110) was found in cirrhotic patients which confirms previous reports that demonstrated a peptic ulcer prevalence ranging from 5% to 20% [5-7]. 61% of patients with gastroduodenal erosions showed a gastric mucosal colonization with H. pylori. In the normal population, almost all patients with duodenal ulcer disease are infected with H. pylori, and a causal relationship is well established [1, 2]. In addition, a strong correlation between gastric erosions and H. pylori has also been shown [1, 2]. Since the peptic ulcer prevalence is considerably higher in cirrhotics than in the normal population, it is reasonable to postulate that there are “ulcerogenic factors” specific to cirrhotic patients which may cause gastro-duodenal ulcers in the absence of H. pylori infection and which could additionally increase the ulcerogenic effects of H. pylori infection. Eradication of H. pylori is successful in 82.6% in cirrhotic patients [25], but the eradication of H. pylori in patients with cirrhosis did not effectively reduce the recurrence of ulcers [9].

Several possible ulcerogenic factors/ mechanisms have been suggested in cirrhotic patients: a decrease in gastric prostaglandin E2 levels [26], hypergastrinemia [27], portosys-temic shunting allowing the ulcerogenic factors to escape hepatic clearance, and an impairment of gastric mucosal defence secondary to portal hypertension and congestive gastropathy [28] which may make the mucosa more susceptible to damage from other agents or reduce its capacity to repair damage [29, 30]. In the present study, 78% of the patients with gastroduo-denal ulcers had features of congestive gastropathy or esophageal/gastric varices which is line with the latter hypothesis. Interestingly, presence of congestive gastropathy or varices did not seem to predispose to H. pylori colonization, since the prevalence rates in these subgroups were lower than in that with normal gastric mucosal appearance. This agrees with a previous report demonstrating a reduced H. pylori colonization in patients with severe gastropathy [31, 32]. Taken together, the pathogenic mechanisms of peptic ulcer disease in cirrhotic patients seems to be a multifactorial event.

The role of the etiology of cirrhosis on the prevalence of H. pylori is up to now controversial. In our study the etiology of cirrhosis did not influence significantly H. pylori prevalence or the occurrence of gastroduodenal lesions. Our findings are in accordance with former studies [5, 33]. In contrast, two other studies found that peptic ulcers were more frequent in patients with chronic hepatitis C [34] and among hepatitis B antigen positive cirrhotic patients of unknown H. pylori status [6], while Rabinovitz et al. reported an increased duodenal ulcer frequency in patients with alcohol-toxic liver cirrhosis, hepatitis B virus infection, and primary scle-rosing cholangitis, again, ignoring the role of H. pylori [35]. Further studies are needed to find out whether the etiology of cirrhosis is of importance for ulcerogenesis, current data argue against a major pathogenic role of etiology of cirrhosis.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that H. pylori serologic prevalence is significantly higher than the gastric mucosal colonization with H. pylori in cirrhotic patients. Liver cirrhosis is associated with a high frequency of gastroduodenal ulcers, which are frequently asymptomatic. Our findings of a lack of a firm association between H. pylori prevalence and ulcer frequency in cirrhotic patients argues against a pivotal role of H. pylori in the etiology of ulcers in cirrhotic patients.

References

- 1.Suerbaum S, Michetti P. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1175–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cover TL, Blaser MJ. H. pylori in health and disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1863–1873. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagner S, Beil W, Westermann J, et al. Regulation of gastric epithelial cell growth by Helicobacter pylori: evidence for a major role of apoptosis. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1836–47. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saadat I, Higashi H, Umeda M, et al. Helicobacter pylori CagA targets PAR1/MARK kinase to disrupt epithelial cell polarity. Nature. 2007;447:330–333. doi: 10.1038/nature05765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen LS, Lin HC, Hwang SJ, Lee FY, Hou MC, Lee SD. Prevalence of gastric ulcer in cirrhotic patients and its relation to portal hypertension. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;11:59–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1996.tb00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siringo S, Burroughs AK, Bolondi L, et al. Peptic ulcer and its course in cirrhosis: an endoscopic and clinical prospective study. J Hepatol. 1995;22:633–641. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80219-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsai CJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and peptic ulcer disease in cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:1219–25. doi: 10.1023/a:1018899506271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vergara M, Calvet X, Roque M. Helicobacter pylori is a risk factor for peptic ulcer disease in cirrhotic patients. A meta.analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:717–722. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200207000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lo GH, Yu HC, Chan YC, et al. The effects of eradication of Helicobacter pylori on the recurrence of duodenal ulcers in patients with cirrhosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:350–356. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)01633-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seckin Y, Harputluoglu MMM, Batcioglu K, et al. Gastric tissue oxidative changes in portal hypertension and cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1154–1158. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rabinovitz M, Yoo Y-K, Schade RR, Dindzans VJ, Van Thiel DH, Gavaler JS. Prevalence of endo-scopic findings in 510 consecutive individuals with liver cirrhosis evaluated prospectively. Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35:705–10. doi: 10.1007/BF01540171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siringo S, Vaira D, Menegatti M, et al. High prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in liver cirrhosis: relationship with clinical and endoscopic features and the risk of peptic ulcer. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:2024–2030. doi: 10.1023/a:1018849930107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu CS, Lin CY, Liaw YF. Helicobacter pylori in cirrhotic patients with pepticulcer disease: a prospective, case controlled study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:424–427. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(95)70044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Villalan R, Maroju NK, Kate V, Ananthakrishnan N. Is Helicobacter pylori eradication indicated in cirrhotic patients with peptic ulcer disease? Trop Gastroenterol. 2006;27:166–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tzathas C, Triantafyllou K, Mallas E, Triantafyllou G, Ladas SD. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication and antisecretory maintenance therapy on peptic ulcer recurrence in cirrhotic patients: a prospective, cohort 2-year follow-up study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:744–749. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3180381571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen JJ, Changchien CS, Tai DI, Chiou SS, Lee CM, Kuo CH. Role of Helicobacter pylori in cirrhotic patients with peptic ulcer. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:1565–1568. doi: 10.1007/BF02088065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calvet X, Navarro M, Gil M, et al. Seroprevalence and epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 1997;26:1249–54. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(97)80459-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pellicano R, Leone N, Berrutti M, et al. Helicobacter pylori seroprevalence in hepatitis C virus positive patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2000;33:648–50. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0641.2000.033004648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Auroux J, Lamarque D, Roudot-Thorabval F, et al. Gastroduodenal ulcer and erosions are related to portal hypertensive gastropathy and recent alcohol intake in cirrhotic patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:1118–1123. doi: 10.1023/a:1023772930681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCormack TT, Sims J, Eyre-Brook I, et al. Gastric lesions in portal hypertension: inflammatory gastritis or congestive gastropathy? Gut. 1985;26:1226–1232. doi: 10.1136/gut.26.11.1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paquet KJ. Prophylactic endoscopic sclerosing treatment of the esophageal wall in varices - a prospective controlled randomised trail. Endoscopy. 1982;14:4–5. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1021560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin JH, Potthoff A, Ledig S, et al. Effect of h. pylori on the expression of TRAIL, FasL and their receptor subtypes in human gastric epithelial cells and their role in apoptosis. Helicobacter. 2004;9:371–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-4389.2004.00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hui WM, Lam SK, Chau PY, et al. Persistence of Campylobacter pyloridis despite healing of duodenal ulcer and improvement of accompanying duodenitis and gastritis. Dig Dis Sci. 1987;32:1255–1260. doi: 10.1007/BF01296375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nardone G, Coscione P, D∼Armiento FP, et al. Cirrhosis negatively affects the efficiency of sero-logic diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1996;28:332–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jung SW, Lee SW, Hyun JJ, et al. Efficacy of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in chronic liver disease. Dig Liver Disease. 2009;41:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arakawa T, Satoh H, Fukada T, Nakamura H, Kobayashi K. Endogenous prostaglandin E2 in gastric mucosa of patients with alcoholic cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:135–40. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90325-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samloff IM. Multiple gastric red spots, capillary ectasia, hypergastrinemia and hypopepsino-genemia I in cirrhosis: a new syndrome? Hepatology. 1988;8:699–700. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840080350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guslandi M, Foppa L, Sorghi M, Pellegrini A, Fanti L, Tittobello A. Breakdown of mucosal defences in congestive gastropathy in cirrhotics. Liver. 1992;12:303–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0676.1992.tb00577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balan KK, Jones AT, Roberts NB, Pearson JP, Critchley M, Jenkins SA. The effects of Helicobacter pylori colonization on gastric function and the incidence of portal hypertensive gastropathy in patients with cirrhosis of the liver. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1400–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perini RF, Camara PR, Ferraz JG. Pathogenesis of portal hyertensive gastropathy: translating basic research into clinical practice. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:150–8. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Batmanabane V, Kate V, Ananthakrishnan N. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in patients with portal hypertensive gastropathy - a study from South India. Med Sci Monit. 2004;10:133–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bahnacy A, Kupcsulik P, Eles Z, Jaray B, Flautner L. Helicobacter pylori and congestive gastropathy. Z Gastroenterol. 1997;35:109–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmulson MJ, De Leon G, Kershenovich A, Vargas-Vorackova F, Kershenobich D. Helicobacter pylori infection among patients with alcoholic and non-alcoholic cirrhosis. Helicobacter. 1997;2:149–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.1997.tb00077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim DJ, Kim HY, Kim SJ, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and peptic ulcer disease in patients with liver cirrhosis. Korean J Internal Med. 2008;23:16–21. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2008.23.1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rabinovitz M, Schade RR, Dindzans VJ, Van Thiel DH, Gavaler JS. Prevalence of duodenal ulcer in cirrhotic males referred for duodenal ulcer in cirrhotic males referred for liver transplantation -does the etiology of cirrhosis make a difference? Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35:321–6. doi: 10.1007/BF01537409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]