Abstract

Background/Objectives:

To assess the iron status among European adolescents through selected biochemical parameters in a cross-sectional study performed in 10 European cities.

Subjects/Methods:

Iron status was defined utilising biochemical indicators. Iron depletion was defined as low serum ferritin (SF<15 μg/l). Iron deficiency (ID) was defined as high-soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR>8.5 mg/l) plus iron depletion. Iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) was defined as ID with haemoglobin (Hb) below the WHO cutoff for age and sex: 12.0 g/dl for girls and for boys aged 12.5–14.99 years and 13.0 g/dl for boys aged ⩾15 years. Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay was used as analytical method for SF, sTfR and C-reactive protein (CRP). Subjects with indication of inflammation (CRP >5 mg/l) were excluded from the analyses. A total of 940 adolescents aged 12.5–17.49 years (438 boys and 502 girls) were involved.

Results:

The percentage of iron depletion was 17.6%, significantly higher in girls (21.0%) compared with boys (13.8%). The overall percentage of ID and IDA was 4.7 and 1.3%, respectively, with no significant differences between boys and girls. A correlation was observed between log (SF) and Hb (r=0.36, P<0.01), and between log (sTfR) and mean corpuscular haemoglobin (r=−0.30, P<0.01). Iron body stores were estimated on the basis of log (sTfR/SF). A higher percentage of negative values of body iron was recorded in girls (16.5%) with respect to boys (8.3%), and body iron values tended to increase with age in boys, whereas the values remained stable in girls.

Conclusions:

To ensure adequate iron stores, specific attention should be given to girls at European level to ensure that their dietary intake of iron is adequate.

Keywords: anaemia, iron deficiency, adolescent, Europe

Introduction

Iron Deficiency (ID) continues to be one of the most prevalent nutritional deficiencies in the world, particularly in developing countries (World Health Organization (WHO), 2003). WHO estimated that ID occurs in about 66–80% of the world's population (WHO, 2003). ID has many negative effects on health, including changes in immune function, cognitive development, temperature regulation, energy metabolism and work performance (Dallman, 1986). On the other hand, iron is a pro-oxidant and thus a possible risk factor for coronary heart disease. However, a recent review suggests that there is no strong association between body iron stores and coronary heart disease in adults (Zegrean, 2009).

The diagnosis of ID is based primarily on laboratory measurements of biochemical iron indicators. There is no full international consensus on the indicators to be used for assessing iron status, as each indicator has its own limitations because of either poor sensitivity or specificity, or because it is modified by conditions other than ID (Dallman et al., 1993). There are three general approaches to assess ID in populations. In the first one, used in studies conducted by Hallberg et al. (Hallberg et al., 1993) and Amstrong (Amstrong, 1989), ID is defined as a low level of serum ferritin (SF). In the second one, used in the US in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) II and III, the multiple-criteria model is used to classify ID; it consists of two or three abnormal values for transferrin saturation, SF and erythrocyte protoporphyrin (Cogswell et al., 2009). The main limitation of these two approaches is that inflammation leads to high ferritin values, even though iron stores are low. The third approach proposed by WHO (2004) and adopted by Zimmermann (2008) is based on the measurements of SF and soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR) in combination with C-reactive protein (CRP) to eliminate false negative cases in presence of inflammation. The third approach was considered more appropriate and was therefore used in the present study. It is well known that SF concentrations reflect the size of the iron stores (Cook, 1999) and that low SF levels identify ‘iron depletion' (WHO, 2001). On the other hand, the measurement of sTfR has been reported to be useful in the diagnosis of ‘tissue ID' (Skikne et al., 1990) and its values are not influenced by acute or chronic inflammatory conditions (Ferguson et al., 1992; Olivares et al., 1995). An approach to estimate body iron was developed by Cook et al. (Cook et al., 2003) using the formula: body iron (mg/kg)=−(log(sTfR/SF)−2.8229)/0.1207 to allow the full range of the iron status of a population to be evaluated ,with negative values representing a deficit of iron with respect to the quantity required to maintain a normal haemoglobin (Hb) concentration.

Adolescents are at risk of ID because of their high iron requirements, especially during the growth spurt period (Moreno, 2008). In boys, increased muscular growth leads to increased demand for iron. In girls, in addition to the fast growth, the onset of menstruation leads to iron losses (Wharton and Wharton, 1987). As a consequence, ID occurs in adolescents also in developed countries, if their additional iron needs are not met (Dallman et al., 1996). Some studies suggested that ID can have detrimental effects on memory and learning processes in preadolescents and adolescents (Beard and Connor, 2003).

The data available on iron status in European adolescents, are derived from studies utilising different methodologies, different indicators of iron status and varying criteria to define ID (Hercberg et al., 2001). There was, therefore, a need to investigate the situation of ID among European adolescents with a harmonised methodology.

Within the framework of the HELENA Study (Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescents), funded within the 6th EU framework programme, a biochemical evaluation of iron status was performed with a cross-sectional approach. The objective of the present paper is to report the iron status of European adolescents.

Materials and methods

Study design and sample selection

A detailed description of HELENA-cross-sectional study (HELENA-CSS) in terms of sampling and recruitment approaches, standardisation and harmonisation processes, data collection, analysis strategies and quality-control activities has been published elsewhere (Moreno et al., 2008). The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committees of each country involved according to the Declaration of Helsinki and International Conferences on Harmonization for Good Clinical Practice. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of the adolescents and the adolescents themselves (Béghin et al., 2008). Briefly, subjects with an age range of 12.5–17.49 years were recruited in 10 cities across Europe. Selection of cities was based on two criteria: regional distribution and presence of an active research group assuring sufficient expertise and resources to successfully perform epidemiological studies. Within the study, Stockholm (Sweden) represented Northern Europe. Athens, Heraklion (Greece), Rome (Italy) and Zaragoza (Spain) represented Southern Europe. Pecs (Hungary) represented Eastern Europe. Ghent (Belgium) and Lille (France) represented Western Europe, whereas Dortmund (Germany) and Vienna (Austria) represented Central Europe. As the overall aim of the HELENA Study was to assess the nutritional status of the adolescent population in Europe, during the design phase, the variability of a large set of nutritional status indices obtained in previous studies was checked. Body mass index was the indicator that showed the largest variability. Therefore, the sample size was estimated according to the mean body mass index and variance values for each sex and age strata. This procedure ensured to adequately describe all the variables included in the study. For the sample size calculation, a confidence level of 95% and an error of ± 0.3 kg/m2 were assumed, leading to a sample size of 3000 adolescents. More details on the procedure are provided by Moreno et al. (2008).

Blood sampling was performed in one-third of the adolescents recruited. Therefore, the total expected subsample was 1000 adolescents (100 subjects for each city). The size of subsample was chosen, so as to assess the immunological parameters with sufficient precision. Such parameters were those with the highest variability within the blood measurements that were included in the study as discussed by Moreno et al. (2008). The selection procedure for schools and classes including the selection of a subset of classes for blood sampling has been applied centrally by one partner (Ghent) for all study centres.

Blood sampling and laboratory measures

The blood sampling procedure and sample logistics have been described in detail elsewhere (González-Gross et al., 2008). Briefly, fasting blood samples were collected by venipuncture at school between 0800 and 1000 hours in the morning. Whole-blood samples for the red blood parameters (Hb, red blood cell, mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular haemoglobin (MCH), mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration and red cell distribution width) were sent directly to the local laboratory of each country to be analysed. Samples for iron status analyses were clotted at room temperature for at least 30 min, followed by centrifuged at 3500 r.p.m. for 10 min. Serum samples were shipped to the central laboratory in Bonn University (IEL, Germany), Department of Nutrition and Food Science, to be stored at −80 °C before being shipped to Italy in May 2007, within 6 months of the collection. The aliquots of serum samples were analysed in the Human Nutrition Laboratory of the National Research Institute on Food and Nutrition (INRAN). SF, sTfR and CRP were measured by using an enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (Erhardt et al., 2004). A commercially available control sample from Bio-Rad Liquichek Immunology Control Level 3 (Bio-Rad, Milan, Italy) was used to obtain a calibration curve on each plate.

A quality-control serum was produced in house by pooling human serum from four healthy volunteers to monitor accuracy and precision of the determinations. The coefficient of variation from 10 replicates of the quality-control serum pool was 5.3, 6.4 and 12.4% for SF, sTfR and CRP, respectively. Additionally, the interassay coefficient of variation of the pool samples analysed in a total of 32 different analytical runs (four replicates) was 10.8, 14.8 and 23.4% for SF, sTfR and CRP, respectively.

INRAN laboratory is involved in an external quality assurance program of CDC Vital-Eqa for SF, sTfR and CRP analyses (Haynes et al., 2008). In Spring 2007, the measures of iron indicators of this study were within the acceptable range, except for CRP that was just below the inferior limit (2.42 mg/l versus an acceptable range of 2.70–5.38 mg/l) and sTfR that was at the superior limit (7.3 mg/l versus an acceptable range of 1.7 and 7.3 mg/l).

Anaemia and iron classification

Anaemia was defined as Hb concentration below the cutoff set by WHO (WHO, 2004), 12.0 g/dl for girls aged 12 years and above, and for boys aged 12–14; and 13.0 g/dl for boys aged 15 years or above. Abnormal values for iron indicators were defined as concentration <15 μg/l for low SF (WHO, 2004), >200 μg/l and >150 μg/l (boys and girls, respectively) for high SF (WHO, 2004; severe risk of iron overload) and >8.5 mg/l for high sTfR (Cook et al., 1993). A participant was considered to have active inflammation, if the CRP concentration exceeded 5 mg/l (Woodruff et al., 2006). The methodology to classify the iron status is described in Table 1. The classification of iron status is considered in presence of normal CRP concentration.

Table 1. Iron statusa as defined in the present paper.

| Classification | Values of iron indicators | |

|---|---|---|

| SF (μg/l) | sTfR (mg/l) | |

| Iron sufficiencyb | ⩾15 | ⩽8.5 |

| Iron depletionc | <15 | ⩽8.5 |

| IDb | <15 | >8.5 |

| IDA | <15 | >8.5 |

Abbreviations: CRP, C-reactive protein; ID, iron deficiency; IDA, iron deficiency with anaemia; SF, serum ferritin; sTfR, soluble transferrin receptor.

Iron status is considered in the presence of CRP<5 mg/l.

With or without anaemia.

Without ID and with or without anaemia.

Total body iron was estimated with the use of the formula: body iron (mg/kg)=−(log(sTfR/SF)−2.8229)/0.1207 (Cook et al., 2003).

Statistical analyses

The Kruskal–Wallis test was used for comparing haematological parameters among iron sufficiency, iron depletion and ID. The Student's t-test was used to evaluate the significance of differences between mean values of iron indicators between genders. Pearson correlation was used to test the linear relation between haematological variables. The χ2-test was used for comparing proportions. Iron status indicators, such as sTfR and SF, were transformed to logarithms before performing statistical analyses. The results in the tables are shown using the original units without any log transformation.

As already performed by Ortega et al. (Ortega et al., 2010), all the analyses conducted on the HELENA data were adjusted by a weighing factor to balance the sample according to the age and sex distribution of the theoretical sample to guarantee representation of each of the stratified groups. The counts of subjects (n) are reported in the tables as unweighted values. All the statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical software package for Microsoft Windows (version 12.00, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Iron indicators and iron status

The HELENA-CSS consists of 1089 adolescent subjects with blood measurements. A total of 102 subjects were excluded because at least one of the iron indicators (SF, n=80; sTfR, n=84) or Hb (n=16) was missing. The final sample of 987 adolescents included 465 boys and 522 girls, that is, 90.7% of the adolescents who participated in the blood sampling.

A total of 47 subjects had high levels of CRP (27 boys and 20 girls) and were excluded. Therefore, the present study of iron status was performed on a total of 940 adolescents (438 boys and 502 girls), with no indication of the presence of inflammation.

The mean age (standard deviation) of adolescents was 14.7 (1.2) years both in boys and in girls, and the mean body mass index was 21.2 (3.8) and 21.1 (3.3) kg/m2, respectively, for boys and girls. The reported age of menarche in the present study ranged from 9 to 16 years of age. A total of 58 (12%) girls reported not to have experienced menarche at the time of the study. In all, 39 and 43% of the boys and girls, respectively, declared to have smoked cigarettes at least once. Mean, median and percentiles (25–75th) values of red blood parameters, SF and sTfR are summarised in Table 2. Percentage of iron sufficiency, abnormal values of iron indicators, anaemia, iron depletion, ID and iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) are presented in Table 3.

Table 2. Haemoglobin, red blood and iron status parameters in European adolescentsa.

| Parameter | Boys (n=438)b | Girls (n=502)b | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | s.d. | Me | 25–75th percentiles | M | s.d. | Me | 25–75th percentiles | ||

| Hb | g/dl | 14.7 | 1.2 | 14.7 | 14.0–15.6 | 13.8 | 1.2 | 13.4 | 12.8–14.1 |

| RBC | 1012/l | 5.2 | 0.4 | 5.1 | 4.9–5.4 | 4.7 | 0.4 | 4.7 | 4.5–4.9 |

| MCV | fl | 83.6 | 4.6 | 84.0 | 81.5–86.2 | 84.9 | 5.1 | 85.5 | 82.4–88.2 |

| MCH | pg | 28.6 | 1.9 | 28.8 | 27.7–29.8 | 28.6 | 2.1 | 29.0 | 29.0–30.0 |

| MCHC | g/dl | 34.3 | 1.0 | 34.2 | 33.6–34.9 | 33.7 | 1.0 | 33.7 | 33.7–34.3 |

| RDW | % | 12.9 | 0.9 | 12.9 | 12.5–13.3 | 12.9 | 1.1 | 12.8 | 12.8–13.4 |

| SF | μg/l | 36.6* | 23.9 | 32.0 | 17.9–49.3 | 27.9 | 19.7 | 24.1 | 24.1–38.0 |

| STfR | mg/l | 5.9 | 1.9 | 5.8 | 4.6–7.0 | 6.0 | 3.3 | 5.7 | 5.7–7.0 |

Abbreviations: Hb, haemoglobin; M, mean; Me, median; MCH, mean corpuscular haemoglobin; MCHC, mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; RBC, red blood cells; RDW, red cell distribution width; SF, serum ferritin; sTfR, soluble transferrin receptor.

All data were adjusted by a weighing factor to balance the sample according to the theoretical age distribution of the European adolescent population.

The count of subjects (n) are reported in the table as unweighted values.

The data are presented as M, s.d., Me and 25th and 75th percentiles

*P<0.05 statistically significant difference between mean values in boys and girls.

Table 3. Proportion of European adolescents having anaemia, abnormal values of iron indicators, iron sufficiency, iron depletion, ID and IDAa.

| Iron statusc | Total (n=940)b | Boys (n=438)b | Girls (n=502)b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Low SF | 210 | 22.4 | 78 | 17.9** | 132 | 26.3 |

| High sTfR | 66 | 7.0 | 30 | 6.9 | 36 | 7.2 |

| Anaemia | 41 | 4.4 | 8 | 1.8** | 33 | 6.6 |

| Classificationd | ||||||

| Iron sufficiency | 705 | 75.2 | 344 | 79.3* | 361 | 71.7 |

| Iron depletion | 167 | 17.6 | 63 | 13.8* | 104 | 21.0 |

| ID | 45 | 4.7 | 18 | 3.9 | 27 | 5.4 |

| IDA | 11 | 1.3 | 2 | 0.5 | 9 | 2.0 |

Abbreviations: ID, iron deficiency; IDA, iron deficiency with anaemia; SF, serum ferritin; sTfR, soluble transferrin receptor.

All data were adjusted by a weighing factor to balance the sample according to the theoretical age distribution of the European adolescent population.

The count of subjects (n) are reported in the table as unweighted values.

Indicators and cutoff values used to identify abnormal values of iron indicators and iron status are reported in Table 1.

23 subjects (13 boys and 10 girls) were excluded because of with high values of sTfR and normal values of SF.

*P<0.05; **P<0.01 statistically significant between girls and boys.

In boys, the mean (standard deviation) of Hb was 14.7 (1.2) g/dl (14.3 (1.0) g/dl aged 12.5–14.99 years and 15.2 (1.2) g/dl aged 15 years or above). In girls it was 13.8 (1.2) g/dl. The mean values of SF suggest a gender-related significant difference (P<0.05) with a lower mean SF value in girls (27.9 μg/l) than in boys (36.6 μg/l). The percentage of low SF values was also higher in girls (26.3%) compared with boys (17.9%) (P<0.01) (Table 3). No single case of high level of SF was identified (SF>200 μg/l for boys and >150 μg/l for girls), indicating no risk of iron overload (WHO, 2004) in the study sample.

A total of 23 subjects had high values (>8.5 mg/l) of sTfR (that could have indicated ID) but with normal values of SF (indicating no iron depletion), and could therefore not be categorised in one of the iron status classifications (Table 1). They were excluded from the analyses in terms of the classification of ID.

The percentage of iron depletion was 17.6%, significantly higher in girls (21.0%) than in boys (13.8%) (P<0.05) (Table 3).

The overall prevalence of anaemia was 4.4% and it ranged from 1.1% (Stockholm) to 10.1% (Heraklion) among cities. Intermediate prevalences were 1.4% for Zaragoza, 3.2% for Pecs, 3.6% for Dortmund, 4.0% for Rome, 4.6% for Ghent, 5.5% for Lille, 5.6% for Vienna and 5.7% for Athens. The overall prevalence of anaemia without ID was 3.1% (4.6% in girls and 1.4% in boys) and ranged from 0% (Stockholm and Zaragoza) to 7.6% (Heraklion). The second highest prevalence was observed in Athens (5.7%). Intermediate prevalences were 1.8% for Dortmund, 1.9% for Vienna, 3.0% for Rome, 3.2% for Pecs, 4.1% for Lille and 4.6% for Ghent. Percentage of iron depletion ranged from 9.6% (Zaragoza) to 23.0% (Pecs). Percentage of ID ranged from 0% (Lille) to 11.3% (Athens). Percentage of IDA ranged from 0% (Athens, Gent, and Pecs) to 2.8 % (Vienna).

Among adolescents with anaemia (n=40), 27.5% (n=11) were classified as IDA, with abnormal SF and sTfR values, whereas 24.3% (n=10) had abnormal SF values but with normal sTfR values (iron depletion without ID) and 47.5% (n=19) had anaemia without ID, with normal SF and sTfR values.

Log(SF) and log(sTfR) were significantly correlated with the red cell parameters (MCV, MCH, mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration and red cell distribution width) (Table 4). In the total sample, a significant correlation was observed between log(SF) and Hb concentration (r=0.36, P<0.01), and between log(SF) and log(sTfR) (r=0.33, P<0.01). For log(sTfR), a significant correlation was observed with log(SF), MCH (r= 0.30, P<0.01) and MCV (r=−0.26, P<0.01) No significant correlation was observed between red blood cell and iron indicators (log(SF) and log(sTfR); r=0.13 and r=0.07, respectively).

Table 4. Pearson correlation coefficients and significance of correlations (P) between iron parametersa (n=940)b.

| Hb | RBC | MCV | MCH | MCHC | RDW | Log(SF) | Log(sTfR) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | ||||||||

| Log(SF) | 0.25** | 0.11* | 0.17** | 0.19** | 0.10** | −0.14** | — | −0.25** |

| Log(sTfR) | 0.16** | 0.07 | −0.16** | −0.22** | −0.20** | 0.09** | −0.25** | — |

| Girls | ||||||||

| Log(SF) | 0.35** | 0.004* | 0.34** | 0.41** | 0.40** | −0.42** | — | −0.39** |

| Log(sTfR) | 0.21** | 0.11 | −0.32** | −0.35** | −0.29** | 0.35** | −0.39** | — |

| Total | ||||||||

| Log(SF) | 0.36** | 0.13 | 0.24** | 0.32** | 0.32** | −0.31** | — | −0.33** |

| Log(sTfR) | 0.16** | 0.07 | −0.26** | −0.30** | −0.24** | 0.26** | −0.33** | — |

Abbreviations: Hb, haemoglobin; MCH, mean corpuscular haemoglobin; MCHC, mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; RBC, red blood cells; RDW, red cell distribution width; SF, serum ferritin; sTfR, soluble transferrin receptor.

All data were adjusted by a weighing factor to balance the sample according to the theoretical age distribution of the European adolescent population.

The count of subjects (n) are reported in the table as unweighted values.

*P<0.05; **P<0.01 boys versus girls.

The mean of red cell parameters in the different classification of iron status is reported in Table 5. Statistically significant differences between iron sufficiency, iron depletion and ID were observed for red cell parameters for boys and girls. There were significant differences (P<0.001) for Hb, MCV, MCH, mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration and red cell distribution width between iron sufficiency group and the iron depletion and ID groups. No significant difference was observed between iron sufficiency group and ID group for any of the red cell parameters considered.

Table 5. Haematological characteristics according to iron sufficiency, iron depletion and IDa.

| Iron sufficiency | Iron depletion | ID | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys (n=344)b | Girls (n=361)b | Total (n=705)b | Boysc (n=63)b | Girls (n=104)b | Total (n=167)b | Boys (n=18)b | Girls (n=27)b | Total (n=45)b | |

| Mean Hb, g/dl (s.d.) | 14.9 (1.2) | 13.6 (0.9) | 14.2 (1.2)* | 14.4 (1.0) | 13.3 (1.6) | 13.7 (1.4) | 13.7 (0.9) | 12.0 (1.4) | 12.7 (1.4) |

| Mean RBC, 1012/l (s.d.) | 5.2 (0.4) | 4.7 (0.3) | 4.9 (0.4) | 5.2 (0.4) | 4.7 (0.5) | 4.8 (0.5) | 5.0 (0.4) | 4.8 (0.3) | 4.8 (0.4) |

| Mean MCV, fl (s.d.) | 84.1 (4.4) | 85.7 (4.6) | 84.8 (4.5)* | 82.1 (4.6) | 84.5 (4.5) | 83.4 (4.7) | 82.0 (4.2) | 78.2 (8.0) | 80.1 (6.4) |

| Mean MCH, pg (s.d.) | 28.8 (1.8) | 29.0 (1.8) | 28.8 (1.8)* | 28.0 (1.9) | 28.3 (1.8) | 28.3 (1.9) | 27.6 (1.7) | 25.1 (3.5) | 26.3 (2.9) |

| Mean MCHC, g/dl (s.d.) | 34.3 (1.0) | 33.8 (0.9) | 34.1 (0.9)* | 34.1 (1.0) | 33.5 (0.9) | 33.7 (1.0) | 33.6 (1.0) | 32.0 (1.8) | 32.8 (1.6) |

| Mean RDW, % (s.d.) | 12.9 (0.9) | 12.7 (0.9) | 12.8 (0.9)* | 13.2 (1.0) | 13.2 (1.0) | 13.2 (1.0) | 13.6 (0.9) | 14.6 (2.0) | 14.1 (1.6) |

Abbreviations: Hb, haemoglobin; ID, iron deficiency; MCH, mean corpuscular haemoglobin; MCHC, mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; RBC, red blood cells; RDW, red cell distribution width.

All data were adjusted by a weighing factor to balance the sample according to the theoretical age distribution of the European adolescent population.

The count of subjects (n) are reported in the table as unweighted values.

*P<0.001 statistically different between iron sufficiency, iron depletion and ID.

Estimation of body iron

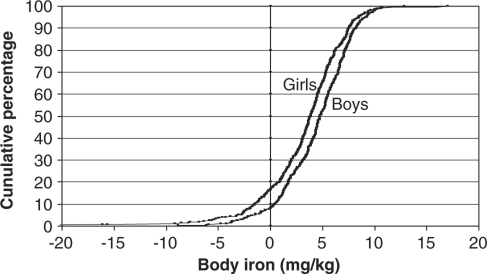

Body iron was calculated according to the formula of Cook et al. (Cook et al., 2003), and the cumulative percentage distributions by gender are shown in Figure 1. Mean (standard deviation) body iron was significantly higher (P<0.001; Student's t-test) in boys (4.4 (3.2) mg/kg) than in girls (3.3 (4.1) mg/kg). Girls showed a light shift of the body iron distribution curve to the left in comparison with boys in which higher positive values were observed. The reference line indicates the cutoff point for tissue ID (body iron <0 mg/kg). The percentage of negative values was significantly higher (P<0.001; χ2) in girls (16.5%) with respect to boys (8.3%).

Figure 1.

Cumulative percentage distributions of estimated body iron in boys and girls from the HELENA Study. Total body iron was estimated using the formula: body iron (mg/kg)=−(log(sTfR:ferritin ratio)−2.8229)/0.1207 developed by Cook (1999) Positive values indicate the presence of storage iron, whereas negative values indicate tissue ID.

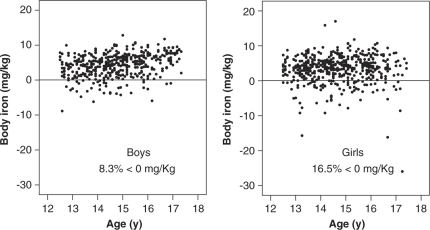

The distribution of body iron stores by age was also examined. Figure 2 shows that the linear relationship between the body iron and the age of the adolescents is not very strong. The body iron increased slightly with age (r=0.28) but this trend did not reach statistical significance. On the other hand, it tended to be stable (r=0.025) in girls.

Figure 2.

Distribution of body iron stores by age in boys and girls in the HELENA Study.

Discussion

The present study is the first report evaluating iron status in adolescents across multiple European countries. As discussed by Moreno et al. (2008), the selected cities were equivalent and comparable between countries but the samples were representative for the cities and not for the countries. Therefore, the HELENA Study does not allow for statistical comparison of differences in iron status between regions. However, the prevalence of iron status stages according to geographical location of the cities adopted for this study are provided underneath for descriptive purpose.

In the present study, the overall proportion of iron depletion was 17.6% it was significantly higher in girls (21.0%) than in boys (13.8%). The prevalence of iron depletion by geographical location was: 23% in Eastern Europe (Pecs), 19% in Northern Europe (Stockholm), 18% in Western Europe (17% in Ghent and 19% in Lille), 17% in Central Europe (16% in Dortmund and 19% in Vienna) and 15% in Southern Europe (14% in Athens, 17% in Heraklion, 19% in Rome and 10% in Zaragoza). These data are in the range of findings from a recent review on iron status in European adolescents (Hercberg et al., 2001) where the highest prevalence of iron depletion was observed in girls in Ireland (43%) and in boys in Denmark (16%), whereas the lowest prevalence was observed in girls in Finland (4.7%) and in boys in France where no cases were detected.

For ID, in the present study, there was a tendency for a higher percentage in girls (5.4%) with respect to boys (3.9%) but the difference was not significant. The percentage of ID in girls in our study was slightly lower than the 8.7% prevalence observed in girls aged 12–16 years in the US (Halterman et al., 2001) but in line with the 6% prevalence observed in girls aged 13–19 years in Canada (Deegan et al., 2005). Both the prevalences observed in our study and in the US are below the cutoff established by WHO to determine ‘no prevalence' of ID, that is, 10% (WHO, 2004). Both are also far lower than that observed in other parts of the world as in Nepal, with an ID prevalence of 56% observed in adolescents girls (Woodruff et al., 2006). The slightly lower prevalence in our study may, in part, result from a different approach to define ID. The impact of ID on the cognitive functioning of adolescent girls who are at the highest risk of ID requires major clarification. In fact, there is only limited evidence that iron supplementation may improve attention, concentration and intelligent quotient (Falkingham et al., 2010). The prevalence of ID by geographical location was: 6% in both Northern Europe (Stockholm) and Southern Europe (11% in Athens, 6% in Heraklion, 3% in Rome and Zaragoza) plus Eastern Europe (Pecs), 5% in Central Europe (3% in Dortmund and 7% in Vienna) and 2% in Western Europe (no cases in Ghent and 4% in Lille). No comparable data are available in the literature in relation to ID in adolescents in the European context for comparison with the results of the present study.

The percentage of IDA was 1.3% (0.5% in boys and 2.0% in girls), with a (non-significantly) higher value in girls. The prevalence of IDA by geographical location was: 2% in Central Europe (2% in Dortmund and 3% in Vienna), 1% in both Northern Europe (Stockholm) and Southern Europe (no cases in Athens, 2% in Heraklion, 1% in both Rome and Zaragoza), 0.6% in Western Europe (no cases in Ghent and 1% in Lille) and no cases in Eastern Europe (Pecs). These data are similar to the estimates of prevalence in adolescents in Canada (Deegan et al., 2005), the United States (Looker et al., 2002) and Sweden (Samulson et al., 1996), ranging from 0 to 3%. In the present study, the proportion of anaemia was 4.4%, consistent with the estimates of the worldwide prevalence of anaemia during adolescence: 27% in developing countries and 6% in developed countries (Kara et al., 2006). The observed prevalence of anaemia not due to ID (3.1%) is probably overestimated because of unavoidable misclassifications that are inherent to the definition of limits. In fact, the limits set to define anaemia are based on 95% reference ranges, and therefore it is assumed that 2.5% of healthy individuals would be classified as anaemic. On the other hand, a proportion of anaemia without ID may be originated from genetic Hb disorders, as subjects with such disorders were not excluded. In our study, the highest prevalence of anaemia without ID among cities was observed in two cities of Greece (7.6% in Heraklion and 6.3% in Athens). Greece is known to be heavily affected by haemoglobinopathies (thalassaemia and sickle-cell disease). In fact, according to Angastiniotis et al. (1995), the highest percentage of carriers of thalassaemia and sickle-cell disorders is observed in Greece (9.0%).

In our study, no single case of iron overload was identified through SF, a stored body iron marker.

Results of the present study on correlations between iron status parameters are all plausible. SF and sTfR that were chosen in this study as iron indicators showed a correlation with red cell parameters. The observed correlation coefficients between log(sTfR) and red cell parameters (MCV and MCH) are not surprising, as sTfR is a measure of ID erytropoiesis (Metzgeroth et al., 2005) as MCV and MCH. The present data are in general agreement with the result of a previous study showing a correlation between sTfR and red cell parameters in iron-deficient adolescents (Choi, 2003). These findings are confirmed, as the concentrations of the mean of red cell parameters decreased gradually (except for red cell distribution width that increased) with increasingly negative iron balance, as ID appeared (sTfR >8.5 mg/l) (Table 5). The results of the present study document a positive correlation between log(SF) level and Hb concentration (r=0.39, P<0.01; Table 3) comparable to those observed in other studies among children: r=0.24 (Jeremiah et al., 2007) and r=0.26 (Ayoya et al., 2010). The low correlation between these two indicators is because of the fact that they are related to differing stages of ID. The correlation between the indicators of iron status and red cell parameters may be considered as a confirmation of the reliability of these indicators (WHO, 2004; Zimmermann, 2008) in the assessment of iron status in adolescents.

The correlation of SF with Hb and the higher percentage of iron depletion in girls with respect to boys suggest that the risk of developing ID anaemia is higher in girls. If iron depletion is not corrected, it may indeed progress to ID. In addition, the calculated measure of body iron was lower in girls than in boys. The distribution of body iron stores by age (Figure 2) suggests that in boys, body iron stores may have slightly increased during and after their rapid growth period, whereas in girls, iron stores remain low during the whole pubertal period. One possible explanation for the lower iron status in girls, besides growth, is the loss of iron with menstruation. In previous studies, it was observed that the growth spurt associated with menstrual status, blood loss and a low iron intake may have adverse effects on iron stores in adolescents girls (Ilich-Ernst et al., 1998).

Conclusions

Our study confirms SF and sTfR as biochemical indicators that could be used in the assessment of iron status in adolescents, a problematic group of population, for the period of rapid growth. On the basis of WHO guidelines (2004) for the interpretation of the iron status data at population level, the results indicate that, in the European context, ID is not prevalent neither in boys nor in girls, and that iron depletion is prevalent in girls but not in boys. Adolescent girls therefore constitute a group at risk of ID, and specific attention should be given to them during adolescence to ensure that their dietary intake of iron is adequate to their requirements.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge all participating adolescents and their parents and teachers for their collaboration. We also acknowledge Dr Eugenia Venneria for her contribution for the enzyme linked immunosorbent assay analyses of serum samples. The HELENA Study was supported financially by the European Community Sixth RTD Framework Programme (Contract FOOD-CT-2005-007034). The content of this article reflects only the author's view, and the European Community is not liable for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.

Appendix

Helena Study group

Co-ordinator: Luis A Moreno

Core group members: Luis A Moreno, Fréderic Gottrand, Stefaan De Henauw, Marcela González-Gross, Chantal Gilbert.

Steering committee: Anthony Kafatos (President), Luis A Moreno, Christian Libersa, Stefaan De Henauw, Jackie Sáchez, Fréderic Gottrand, Mathilde Kesting, Michael Sjostrom, Dénes Molnár, Marcela González-Gross, Jean Dallongeville, Chantal Gilbert, Gunnar Hall, Lea Maes, Luca Scalfi.

Project manager: Pilar Meléndez

Universidad de Zaragoza (Spain): Luis A Moreno, Jesús Fleta, José A Casajús, Gerardo Rodríguez, Concepción Tomás, María I Mesana, Germán Vicente-Rodríguez, Adoración Villarroya, Carlos M Gil, Ignacio Ara, Juan Revenga, Carmen Lachen, Juan Fernández Alvira, Gloria Bueno, Aurora Lázaro, Olga Bueno, Juan F León, Jesús Ma Garagorri, Manuel Bueno, Juan Pablo Rey López, Iris Iglesia, Paula Velasco, Silvia Bel.

Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (Spain): Ascensión Marcos, Julia Wärnberg, Esther Nova, Sonia Gómez, Esperanza Ligia Díaz, Javier Romeo, Ana Veses, Mari Angeles Puertollano, Belén Zapatera, Tamara Pozo.

Université de Lille 2 (France): Laurent Béghin, Christian Libersa, Frédéric Gottrand, Catalina Iliescu, Juliana Von Berlepsch.

Research Institute of Child Nutrition Dortmund, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn (Germany): Mathilde Kersting, Wolfgang Sichert-Hellert, Ellen Koeppen.

Pécsi Tudományegyetem (University of Pécs) (Hungary): Dénes Molnar, Eva Erhardt, Katalin Csernus, Katalin Török, Szilvia Bokor, Mrs Angster, Enikö Nagy, Orsolya Kovács, Judit Repásy.

University of Crete School of Medicine (Greece): Anthony Kafatos, Caroline Codrington, María Plada, Angeliki Papadaki, Katerina Sarri, Anna Viskadourou, Christos Hatzis, Michael Kiriakakis, George Tsibinos, Constantine Vardavas Manolis Sbokos, Eva Protoyeraki, Maria Fasoulaki.

Institut für Ernährungs- und Lebensmittelwissenschaften—Ernährungphysiologie. Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms Universität (Germany): Peter Stehle, Klaus Pietrzik, Marcela González-Gross, Christina Breidenassel, Andre Spinneker, Jasmin Al-Tahan, Miriam Segoviano, Anke Berchtold, Christine Bierschbach, Erika Blatzheim, Adelheid Schuch, Petra Pickert.

University of Granada (Spain): Manuel J Castillo, Ángel Gutiérrez, Francisco B Ortega, Jonatan R Ruiz, Enrique G Artero, Vanesa España-Romero, David Jiménez-Pavón, Palma Chillón.

Istituto Nazionale di Ricerca per gli Alimenti e la Nutrizione (Italy): Davide Arcella, Elena Azzini, Emma Barrison, Noemi Bevilacqua, Pasquale Buonocore, Giovina Catasta, Laura Censi, Donatella Ciarapica, Paola D'Acapito, Marika Ferrari, Myriam Galfo, Cinzia Le Donne, Catherine Leclercq, Giuseppe Maiani, Beatrice Mauro, Lorenza Mistura, Antonella, Pasquali, Raffaela Piccinelli, Angela Polito, Raffaella Spada, Stefania Sette, Maria Zaccaria.

University of Napoli ‘Federico II' Dept of Food Science (Italy): Luca Scalfi, Paola Vitaglione, Concetta Montagnese.

Ghent University (Belgium): Ilse De Bourdeaudhuij, Stefaan De Henauw, Tineke De Vriendt, Lea Maes, Christophe Matthys, Carine Vereecken, Mieke de Maeyer, Charlene Ottevaere.

Medical University of Vienna (Austria): Kurt Widhalm, Katharina Phillipp, Sabine Dietrich.

Harokopio University (Greece): Yannis Manios, Eva Grammatikaki, Zoi Bouloubasi, Tina Louisa Cook, Sofia Eleutheriou, Orsalia Consta, George Moschonis, Ioanna Katsaroli, George Kraniou, Stalo Papoutsou, Despoina Keke, Ioanna Petraki, Elena Bellou, Sofia Tanagra, Kostalenia Kallianoti, Dionysia Argyropoulou, Katerina Kondaki, Stamatoula Tsikrika, Christos Karaiskos.

Institut Pasteur de Lille (France): Jean Dallongeville, Aline Meirhaeghe.

Karolinska Institutet (Sweden): Michael Sjöstrom, Patrick Bergman, María Hagströmer, Lena Hallström, Mårten Hallberg, Eric Poortvliet, Julia Wärnberg, Nico Rizzo, Linda Beckman, Anita Hurtig Wennlöf, Emma Patterson, Lydia Kwak, Lars Cernerud, Per Tillgren, Stefaan Sörensen.

Asociación de Investigación de la Industria Agroalimentaria (Spain): Jackie Sánchez-Molero, Elena Picó, Maite Navarro, Blanca Viadel, José Enrique Carreres, Gema Merino, Rosa Sanjuán, María Lorente, María José Sánchez, Sara Castelló.

Campden and Chorleywood Food Research Association (United Kingdom): Chantal Gilbert, Sarah Thomas, Elaine Allchurch, Peter Burguess.

SIK—Institutet foer Livsmedel och Bioteknik (Sweden): Gunnar Hall, Annika Astrom, Anna Sverkén, Agneta Broberg.

Meurice Recherche and Development asbl (Belgium): Annick Masson, Claire Lehoux, Pascal Brabant, Philippe Pate, Laurence Fontaine.

Campden and Chorleywood Food Development Institute (Hungary): Andras Sebok, Tunde Kuti, Adrienn Hegyi.

Productos Aditivos SA (Spain): Cristina Maldonado, Ana Llorente.

Cárnicas Serrano SL (Spain): Emilio García.

Cederroth International AB (Sweden): Holger von Fircks, Marianne Lilja Hallberg, Maria Messerer.

Lantmännen Food R and D (Sweden): Mats Larsson, Helena Fredriksson, Viola Adamsson, Ingmar Börjesson.

European Food Information Council (Belgium): Laura Fernández, Laura Smillie, Josephine Wills.

Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (Spain): Marcela González-Gross, Agustín Meléndez, Pedro J. Benito, Javier Calderón, David Jiménez-Pavón, Jara Valtueña, Paloma Navarro, Alejandro Urzanqui, Ulrike Albers, Raquel Pedrero, Juan José Gómez Lorente.

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- Amstrong PL. Iron deficiency in adolescents. BMJ. 1989;298:499. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6672.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angastiniotis M, Modell B, Englezos P, Boulyjenkov V. Prevention and control of haemoglobinopathies. Bull Worls Health Organ. 1995;73:375–386. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoya MA, Spiekermann-Brouwer GM, Stolzfus RJ, Nemeth E, Habicht JP, Ganz T, et al. α1-Acis glycoprotein, hepicidin, C-reactive protein and serum ferritin are correlated in anemic schoolchildren with Schistosoma haematobium. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1784–1790. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard JL, Connor JR. Iron status and neural functioning. Annu Rev Nutr. 2003;23:41–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.23.020102.075739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Béghin L, Castera M, Manios Y, Gilbert CC, Kersting M, De Henauw S, et al. Quality assurance of ethical issues and regulatory aspects relating to good practices in the HELENA Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Obes. 2008;32:S12–S18. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JW. Serum transferrin receptor concentrations correlate more strongly with red cell indices than with iron parameters in iron-deficient adolescents. Acta Haematol. 2003;110:213–216. doi: 10.1159/000074231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogswell ME, Looker AC, Pfeiffer CM, Cook JD, Lacher DA, Beard JL, et al. Assessment of iron deficiency in US preschool children and nonpregnant females of childbearing age: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2006. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:1334–1342. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JD. Defining optimal body iron. Proc Nutr Soc. 1999;58:489–495. doi: 10.1017/s0029665199000634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JD, Flowers CH, Skikne BS. The quantitative assessment of body iron. Blood. 2003;101:3359–3364. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JD, Skikne BS, Baynes RD. Serum transferrin receptor. Annu Rev Med. 1993;44:63–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.44.020193.000431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallman PR. Biochemical basis for the manifestations of iron deficiency. Annu Rev Nutr. 1986;6:13–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.06.070186.000305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallman PR, Looker AC, Johnson CL, Caroll M.1996Influence of age on laboratory criteria for the diagnosis of iron deficiency anemia and iron deficiency in infants and childrenIn: Hallberg L, Asp N-G (eds).Iron Nutrition in Health and Disease Libbey: London, England; 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Dallman PR, Yip r, Oski FA.1993Iron deficiency and related nutritional anemiasIn: Nathan DG, Oski FA (eds).Hematology of Infancy and Childhood4th ed.Saunders: Mexico; 413–450. [Google Scholar]

- Deegan H, Bates HM, McCargar LJ. Assessment of iron status in adolescents: dietary, biochemical and lifestyle determinants. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37:75e15–75e21. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erhardt JG, Estes JE, Pfeiffer CM, Biesalski HK, Craft NE. Combined measurement of ferritin, soluble transferrin receptor, retinol binding protein, and C-reactive protein by an inexpensive, sensitive, and simple sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay technique. J Nutr. 2004;134:3127–3132. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.11.3127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkingham M, Abdelhamid A, Curtis P, Fairweather-Tait S, Dye L, Hooper L. The effects of oral iron supplementation on cognition in older children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analyses. J Nutr. 2010;9:1–16. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-9-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson BJ, Skikne BS, Simpson km, Baynes RD, Cook JD. Serum transferrin receptor distinguishes the anemia of chronic disease from iron deficiency anemia. J Lab Clin Med. 1992;19:385–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Gross M, Breidenassel C, Gomez-Martinez S, Ferrari M, Béghin L, Spinneker A, et al. Sampling and processing of fresh blood samples within a European multicenter nutritional study: evaluation of biomarker stability during transport and storage. Int J Obes. 2008;32:S66–S75. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallberg L, Bengtsson C, Lapidus L, Lindstedt G, Lundberg PA, Hulten L. Screening for iron deficiency: an analysis based on bone-marrow examinations and serum ferritin determinations in a population sample of woman. Br J Haematol. 1993;85:787–798. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1993.tb03225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halterman JS, Kaczorowski JM, Aligne CA, Auinger P, Szilagvi PG. Iron deficiency and cognitive achievement among school-aged children and adolescents in the United States. Pediatrics. 2001;107:1381–1386. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes BMH, Schleicher RS, Jain RB, Pfeiffer CM. The CDC VITAL-EQA program, external quality assurance for serum retinol, 2003–2006. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2008;390:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hercberg S, Preziosi P, Galan P. Iron deficiency in Europe. Public Health Nutr. 2001;4:537–545. doi: 10.1079/phn2001139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilich-Ernst JZ, McKenna AA, Badenhop NE, Clairmont AC, Andon MB, Nahhas RW, et al. Iron status, menarche and calcium supplementation in adolescents girls. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68:880–887. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.4.880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeremiah ZA, Buseri FI, Uko EK. Iron deficiency anaemia and evaluation of the utility of iron deficiency indicators among healthy Nigerian children. Hematology. 2007;12:249–253. doi: 10.1080/110245330601111821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kara B, Cal S, Aydo∂an A, Sarper N. The prevalence of anemia in adolescents: a study from Turkey. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2006;28:316–321. doi: 10.1097/01.mph.0000212918.31674.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Looker AC, Cogswell ME, Gunter EW. Iron deficiency-United States, 1999–2000. JAMA. 2002;288:2114–2116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzgeroth G, Adelberger V, Dorn-Beineke A, Kuhn C, Schatz M, Maywald O, et al. Soluble transferrin receptor and zinc protoporphyrin—competitors or efficient partners. Eur J Haematol. 2005;75:309–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2005.00515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno LA.2008AdolescenceIn: Koletzko B (ed).Pediatric Nutrition in Practice Basel, Karger; 114–117. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno LA, De Henauw S, González-Gross M, Kersting M, Molnár D, Gottrand F, et al. Design and implementation of the healthy lifestyle in Europe by nutrition in adolescence Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Obes. 2008;32:S4–S11. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivares M, Walter T, Cook JD, Llaguno S. Effect of acute infection on measurement of iron status: usefulness of the serum transferrin receptor. Int J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1995;2:31–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega FB, Artero EG, Ruiz JR, España-Romero V, Jiménez-Pavón D, Vicente-Rodriguez G, et al. 2010Physical fitness levels among European adolescents: the HELENA study Br J Sports MedJune 11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Samulson G, Bratteby L-E, Berggren K, Elverby J-E, Kempe B. Dietary iron intakes and iron status in adolescents. Acta Paediatr. 1996;85:1033–1038. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1996.tb14212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skikne BS, Flowers CH, Cook JD. Serum transferrin receptor: a quantitative measure of tissue iron deficiency. Blood. 1990;75:1870–1876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wharton B, Wharton P. Nutrition in adolescents. Nutr Health. 1987;4:195–203. doi: 10.1177/026010608700400403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO 2003Micronutrient deficiencies: battling iron deficiency anaemia [online]. Nutrition ProgramAvailable from URL http://www.who.int/mip2001/files/2232/NHDbrochure.pdf .

- WHO 2004Assessing the iron status of populations. Joint World Health Organization/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Technical Consultation on the Assessment of Iron Status at the Population Level (online)6–8 April 2004 (cited 14 June 2006). Geneva, Switzerland. Available at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2004/9241593156_eng.pdfs .

- WHO . Iron Deficiency Anaemia. Assessment, Prevention and Control. A Guide for Programme Managers. UNICEF/United Nations University/WHO: Geneva, Switzerland; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff BA, Blanck HM, Slutsker L, Cookson ST, Larson MK, Duffield A, et al. Anaemia, iron status and vitamin A deficiency among adolescent refugees in Kenya and Nepal. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9:26–34. doi: 10.1079/phn2005825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zegrean M. Association of body iron stores with development of cardiovascular disease in the adult population: a systematic review of the literature. Can J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2009;19:26–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann AM. Methods to assess iron and iodine status. Br J Nutr. 2008;99:S2–S9. doi: 10.1017/S000711450800679X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]