Abstract

Increased evidence from animal and in vitro cellular research indicates that the metabolism of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) can inhibit carcinogenesis in many cancers. Free radical-mediated peroxidation is one of many possible mechanisms to which EPA’s anti-cancer activity has been attributed. However, no direct evidence has been obtained for the formation of any EPA-derived radicals. In this study, a combination of LC/ESR and LC/MS was used with α-[4-pyridyl 1-oxide]-N-tert-butyl nitrone to identify the carbon-centred radicals that are formed in lipoxygenase-catalysed EPA peroxidation. Of the numerous EPA-derived radicals observed, the major products were those stemming from β-scission of 5-, 15- and 18-EPA-alkoxyl radicals. By means of an internal standard in LC/MS, this study also quantified each radical adduct in all its redox forms, including an ESR-active form and two ESR-silent forms. The comprehensive profile of EPA’s radical formation provides a starting point for ongoing research in defining the biological effects of radicals generated from EPA peroxidation.

Keywords: ESR spin-trapping, EPA-derived radicals, LOX-catalysed peroxidation, on-line LC/ESR, on-line LC/MS and LC/MS2

Introduction

Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) is one of the major dietary ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). As a dietary supplement, EPA is incorporated into cellular lipids about 20-times more efficiently than when it is synthesized in the body from dietary linolenic acids [1]. Unlike most of ω-6 PUFAs, which tend to be unhealthy due to their inflammation- and tumour-promoting activities [2–4], intake of a certain amount of ω-3 PUFAs, such as EPA, has been associated with the decreased incidence, growth and spread of a variety of experimental tumours [5,6]. A negative correlation between a high intake of dietary EPA and the growth of certain types of cancer has been demonstrated in many experimental and epidemiological studies [7–9]. For instance, consumption of seafood (low in the ω-6 PUFA arachidonic acid, but rich in EPA) has been reported to be associated with reducing the risks of renal, lung and colorectal cancers [10–12], while consumption of fish oil (a major source of EPA) has also been correlated with reduced risk for a variety of human diseases, including cancer, atherosclerosis, asthma, neurodegenerative disorders and prolonged bleeding time [13–16].

Among many proposed mechanisms, free radical-mediated lipid peroxidation is the most popular one contributing to EPA’s bioactivities, particularly the associated anti-cancer activity [17]. Lipid peroxidation is a well-known free radical chain reaction in which many types of free radicals are formed in three steps: initiation, propagation and termination [18,19]. The starting point for the study of EPA radical-related bioactivity is to determine what kinds and amounts of free radicals could be formed in its peroxidation. However, mainly due to the lack of appropriate methodologies, no direct evidence has previously been found for either the formation of EPA-derived radicals or their associated bioactivities.

Electron spin resonance (ESR) combined with the spin-trapping technique is a unique method of studying the unstable free radicals formed in many chemical and biological systems [20–22]. In this technique, spin trap compounds are used to convert unstable free radicals to relatively stable radicals (spin adducts) in order to measure them by ESR. One of the most common spin traps, the nitrone compound α-[4-pyridyl 1-oxide]-N-tert-butyl nitrone (POBN), preferentially reacts with carbon-centred radicals formed during lipid peroxidation in vitro and in vivo [23–25]. However, since many POBN adducts share identical or similar hyperfine couplings [26], the six-line ESR spectra that are typically observed for POBN adducts in such studies cannot give complete structural and quantitative information for individual trapped radicals. To overcome this limitation of ESR, a combination of the LC/ESR and LC/MS techniques has recently been developed [27–30], enabling one to identify the detailed structures of free radicals formed from lipid peroxidation of many PUFAs in the presence of POBN.

This study used LC/ESR and LC/MS to analyse the spin adducts of carbon-centred radicals formed from soybean lipoxygenase (LOX)-catalysed EPA peroxidation in the presence of POBN. Two classes of EPA-derived radicals, including lipid dihydroxyallylic radicals (•L(OH)2) and a variety of radicals formed from β-scission of lipid alkoxyl radicals, were identified. Among them, the three major LOX-catalysed products were the free radicals stemming from β-scission of 5-, 15- and 18-EPA-alkoxyl radicals. Using an appropriate internal standard, this study also comprehensively quantified each POBN adduct by simultaneously profiling all its redox forms, including the POBN adduct itself (ESR-active) and two ESR-silent forms, namely the hydroxylamine and nitrone adducts. The ability to also profile ESR-silent forms of radical adducts greatly improves the sensitivity and reliability of radical detection and creates a new approach for ongoing investigation of EPA peroxidation and its associated bioactivities.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Ethyl alcohol, glacial acetic acid (HOAc), soybean lipoxygenase (LOX, Type I-B) and ascorbic acid were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Eicosapentaenoic acid was obtained from Nu-Chek-Prep, Inc. (Elysian, MN). High purity α-[4-pyridyl 1-oxide]-N-tert-butyl nitrone (POBN) was purchased from Alexis Biochemicals (San Diego, CA), while deuterium POBN (D9-POBN) was obtained from CDN Isotopes, Inc. (Pointe-Claire, QC, Canada). HPLC grade acetonitrile (ACN) and LC/MS grade water were purchased from Mallinckrodt Baker, Inc. (Phillipsburg, NJ) and EMD Chemicals Inc. (Darmstadt, Germany), respectively. Chelex® 100 resin (200–400 mesh sodium form) was obtained from Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc. (Hercules, CA).

Reaction conditions

All EPA peroxidations were performed in 50 mM (pH 7.5) phosphate buffer aqueous solution which was treated with Chelex® 100 resin (chelating agent) to gain a virtually metal-free solution after passing the ascorbic acid assay [31]. The complete reaction mixture (1% ethyl alcohol), containing 1 mM EPA, 20 mM POBN and 20 Kunit/mL LOX, was continuously stirred at 37°C and 400 rpm on a Thermo-Shaker (Boekel Scientific, Feasterville, PA) in the absence of light.

We found that mixing reaction samples with >20% ACN (v/v) could improve the reliability of measuring real time formation of POBN radical adducts because it completely denatured the LOX enzyme and immediately stopped enzyme-mediated EPA-peroxidation [30]. Thus, at each experimental time point (0.5, 1, 2, 5, 15, 30, 45 and 60 min), aliquots were taken and mixed immediately with an equal volume of ACN. After the LOX enzyme was precipitated and separated from the ACN-sample mixtures using Microfuge® 22R Centrifuge (Beckman Coulter Inc, Fullerton, CA) at 5000 rpm for ~15 min, the sample solutions were ready to be analysed for real time radical formation by off-line ESR analysis. For online LC/ESR and LC/MS analysis, however, the above enzyme-free ACN-sample mixtures were further transferred into new tubes and placed in a Vacufuge™ 5301 Concentrator (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany), where most of the ACN was evaporated at room temperature in ~15 min. These enzyme-free concentrated sample solutions were then either immediately analysed by LC/ESR and LC/MS or stored at −80°C for later analysis.

ESR measurements

Off-line ESR

For the complete reaction system and relevant control experiments, reaction solutions (with or without mixing with ACN, 50% v/v) were transferred to the same ESR flat cell for magnetic field scans. ESR spectra were obtained with a Bruker EMX ESR spectrometer equipped with a super high Q cavity operating at 9.77 GHz and room temperature. Other ESR spectrometer settings were: magnetic field centre, 3494.4 G; magnetic field scan, 70 G; modulation frequency, 100 kHz; microwave power, 20 mW; modulation amplitude, 1.0 G; receiver gain, 5.0×104; time constant, 0.655 s; and conversion time, 0.164 s.

On-line LC/ESR

The on-line LC/ESR system consisted of an Agilent 1200 series HPLC system and the above Bruker EMX ESR. The outlet of the Agilent UV detector was connected to the highly sensitive Aquax ESR cell placed in the ESR cavity with red PEEK HPLC tubing (0.005 in i.d.). The POBN radical adducts were monitored at a UV absorption of 265 nm in the HPLC system [32,33], followed by ESR fixed field detection. There was a 9 s delay between the UV (LC system) and ESR detection.

LC separations were performed on a C18 column (ZORBAX Eclipse-XDB, 3.0×75 mm, 3.5 μm) equilibrated with solvent A (H2O-0.1% HOAc). The enzyme-free condensed sample solution (40 μl) was normally injected into the HPLC column by auto-sampler and eluted at a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min with gradient elution of (i) 0–40 min: 100% to 30% of solvent A, 0% to 70% of solvent B (ACN-0.1% HOAc); (ii) 40–45 min: 30% to 5% of A, 70% to 95% of B; (iii) 45–54 min: 5% of A and 95% of B and (iv) 54–60 min: 5% to 100% of A and 95% to 0% of B.

On-line ESR monitoring consisted of a time scan with the magnetic field fixed on the maximum of the first line of the off-line ESR spectrum. Other ESR spectrometer settings were: modulation frequency, 9.8 GHz; modulation amplitude, 3.0 G; microwave power, 20 mW; receiver gain, 3.8×105; and time constant, 2.6 s.

LC/MS measurements

The LC/MS system consisted of an Agilent 1200 LC system and an Agilent LC/MSD Trap SL Mass Spectrometer. The outlet of the UV detector was connected with the MS system inlet with Red PEEK HPLC tubing. Chromatographic conditions were identical to those used for on-line LC/ESR. However, the LC flow rate (0.8 mL/min) was adjusted to allow an input of 30–40 μl/min into the MS system via a splitter. Positive ions from electrospray ionization (ESI) were analysed for all LC/MS and LC/MS2 experiments. There was a delay of ~35 s between UV detection and the MS detection.

TIC and EIC (LC/MS)

Total ion current chromatogram (TIC) in full mass scan mode (m/z 150 to m/z 600) was performed to profile all products formed from LOX-catalysed EPA peroxidation in the presence of POBN. Other MS settings were: capillary voltage, −4500 V; nebulizer press, 20 psi; dry gas follow rate, 8 L/min; dry temperature, 60°C; compound stability, 20%; and number of averaging scans, 50. An extracted ion current chromatogram (EIC) from the above full scan experiment was obtained to acquire the MS profile matching the POBN trapped radical adducts that were monitored as ESR-active peaks in on-line LC/ESR. An isolation width of m/z ± 0.5 Da was used to obtain EICs of protonated molecular ions of interest.

LC/MS2 identification

LC/MS2 analysis in multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode was performed to confirm the structure assignment for each POBN adduct (ESR-active) as well as its two ESR-silent forms. A 4-Da width was typically used to isolate protonated molecular ions of interest, including all redox forms of each POBN adduct. Other settings were: capillary voltage, −4500 V; nebulizer press, 20 psi; dry gas follow rate, 8 L/min; dry temperature, 60°C; compound stability, 20%; and number of scans, 5.

In order to identify all POBN-related products (ESR-silent adducts particularly), we designed our systematic approach as follows: (1) to screen all POBN-related chromatographic peaks (e.g. monitoring UV 265 nm for molecules with POBN structure) by comparing UV-chromatogram of POBN control (non-POBN) system with that of complete reaction system; (2) to conduct LC/MS analysis for their possible protonated molecular ions with POBN and D9-POBN spin trapping experiments; and (3) to finally confirm structure of POBN adduct (D9-POBN adduct if need) as well as related redox forms by conducting LC/MS2 analysis. An LC/MS2 study of D9-POBN spin trapped products was typically performed for any peaks of POBN adducts or/and related redox forms whose structures were not clearly reflected by fragmentation pattern of LC/MS2 spectra with POBN alone [30,34,35]. All reaction conditions of D9-POBN spin trap experiments were the same as the corresponding POBN spin trapping reaction system, but with POBN replaced by the same amount of D9-POBN.

LC/MS quantification

LC/MS settings for quantification were identical to the above full scan methods. A small and known amount of D9-POBN was used purely as an internal standard in LC/MS quantification. Unlike the above LC/MS2 procedure in which D9-POBN was used as a spin trap for the purpose of structure identification, here it was not added until after the analyte was mixed with a stop-solution (50% ACN, v/v) to completely denature LOX enzymes [30]. Based on the average abundance of many types of POBN radical adducts observed in our complete reaction system within 1 h of reaction, we chose 2.0 μg/mL as the quantity of internal standard D9-POBN to add to the ACN-sample mixture. To quantify the abundance of protonated molecular ions of interest, the integrated EIC peak of m/z 204 for D9-POBN was always used as the standard. Quantanalysis version 1.8 for the 6300 Series Ion trap LC/MS Agilent In-house Version was used to process the integration and calculation.

Results

Off-line ESR study of POBN adducts generated from LOX-catalysed EPA peroxidation

According to the proposed mechanism of EPA peroxidation (Scheme 1), a variety of structurally different radicals could form and be trapped in the presence of POBN. When the complete reaction system, containing EPA, LOX and POBN, was subjected to an off-line ESR study, a spectrum typical of POBN adducts was detected with hyperfine coupling constants of aN≈15.69 G and aH≈2.68 G (Figure 1A). In the control experiment in the absence of POBN, no ESR signal was observed (Figure 1B), suggesting that all the EPA-derived free radicals that are formed are short-lived and that spin traps such as POBN are required for trapping and measuring them by ESR.

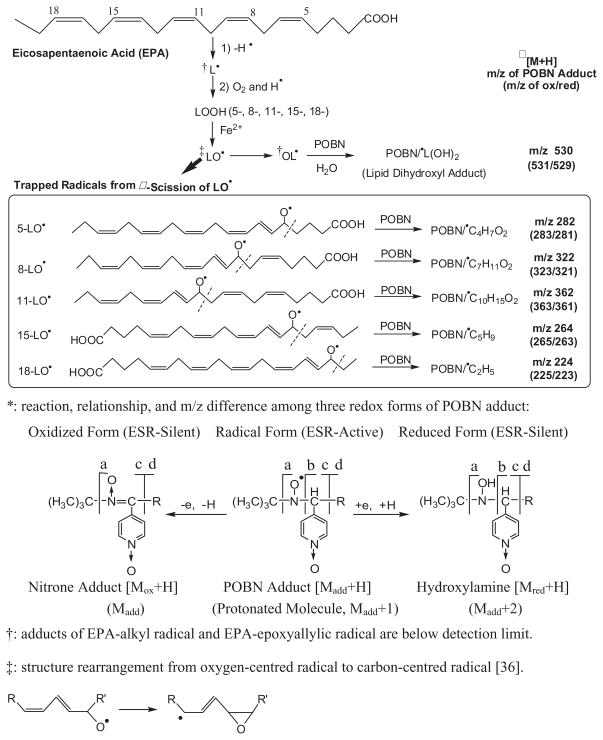

Scheme 1.

Chemistry of formation of spin adducts of carbon-centred radicals in LOX-catalysed EPA peroxidation, the subsequent redox reaction and relationship of the three redox forms of the POBN adduct.

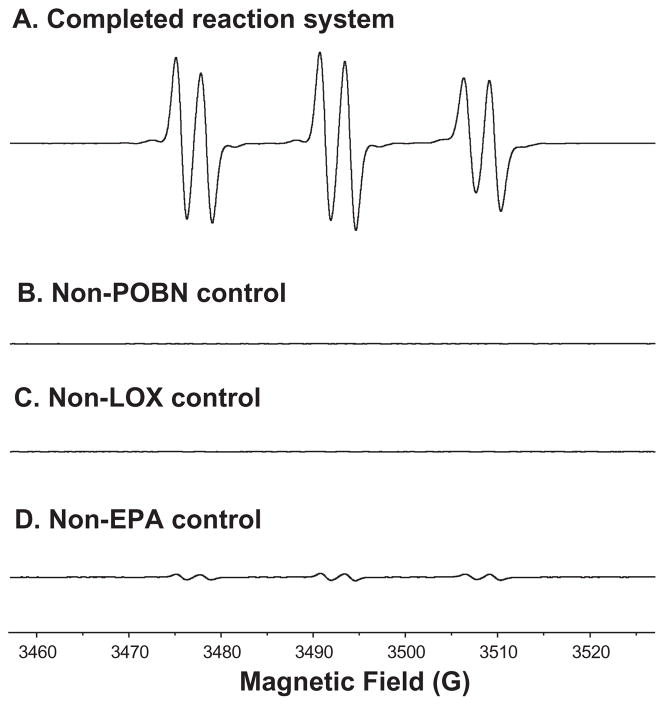

Figure 1.

Off-line ESR spectra of the complete EPA-peroxidation system and the relevant control experiments. (A) ESR spectrum of the complete system at 30 min reaction time. The complete system (50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, 1% ethanol) contained 20 mM POBN, 1 mM EPA and 2×104 Units/mL LOX. An ESR field scan (70 G) was performed and the hyperfine couplings of this spectrum were aN≈15.69 G, aH≈2.68 G; (B, C) ESR spectra of POBN and LOX control experiments. ESR field scans were performed at 30 min reaction time for the complete reaction mixtures absent of POBN and LOX, respectively; (D) ESR spectrum of control experiment of EPA. Reaction mixture excluding EPA (adding EPA stock solution was replaced by addition of the same volume of ethanol) was subjected to ESR field scan at 30 min. Hyperfine coupling constants of this spectrum were aN≈15.71 G, aH≈2.62 G.

For the control experiment excluding LOX enzyme, a very weak signal was detected (Figure 1C) because the presence of trace metal ions can cause a limited reaction from EPA auto-oxidation and subsequent spin trapping. However, in a control experiment in the absence of EPA (Figure 1D), less than 1/10 the ESR signal intensity as that of the complete reaction system (Figure 1A) was observed. The hyperfine coupling constants of aN≈15.71 G and aH≈2.62 G (Figure 1D) were consistent with spectra of the POBN adduct of hydroxyethyl radical (•C2H4OH) published elsewhere [27,28]. This spin trapped radical was formed from ethanol oxidation since the EPA stock solution (in ethanol) was replaced by the same volume of ethanol in the experiment.

As shown in Figure 1, the POBN spin trap technique facilitated ESR detection of carbon-centred radicals in EPA peroxidation and the results suggest that the radical adducts formed from the complete reaction solution mainly resulted from LOX-catalysed EPA peroxidation. However, lipid peroxidation is a reaction well-known to be complicated, in which numerous types of free radicals could form and be trapped in the presence of POBN (Scheme 1). It is impossible to distinguish either numbers or types of carbon-centred radicals from such ESR spectra as Figure 1A because many POBN radical adducts share the same or similar hyperfine couplings [26]. To obtain more specific information about these radicals, we used a combination of LC/ESR and LC/MS [27–30,34,35].

As a preliminary to subjecting our sample solution to a high throughput LC/ESR and LC/MS analysis, we tested the effects of the organic solvent acetonitrile (ACN) on denaturation of LOX enzyme and attenuation of the off-line ESR signal intensity. When LOX enzyme was added to the reaction system having ACN at a proportion > 20% (v/v), LOX activity was completely inhibited and no ESR signal was detected (data not shown). Therefore, at each experimental time point, the reaction was stopped by adding an equal volume of ACN to make a 50% (v/v) sample mixture for high throughput analysis.

LC/ESR, LC/MS and LC/MS2: Identification of ESR-active products

When a gradient separation is performed in conjunction with a larger injection of sample containing organic solvent, it is possible for many analytes to elute out immediately. Even a small portion of organic solvent, e.g. 5% ACN in our case, in the sample mixture could elute sufficient analyte in the organic phase to create very poor retention behaviour in an LC separation [30]. Therefore, in order to obtain a reliable chromatographic separation of analyte, the above ACN-sample solution mixtures (50%, v/v) were subjected to evaporation of all added ACN (returning to the previous volume) before online LC/ESR and LC/MS analysis.

When the above enzyme-free condensed sample was subjected to on-line LC/ESR and LC/MS analysis, a UV chromatogram (absorption at 265 nm, Figure 2A) was obtained. Among numerous UV-active fractions, only a few were ESR active (peaks 1–11, Figure 2B); six of these peaks could be matched with corresponding UV peaks (marked with tRs as ESR peaks 2–4 and 7–9, Figures 2A and B). Under the same chromatographic conditions, the ESR peaks 2–4 and 7–9 (Figure 2B) were also profiled for their possible protonated molecular ions (m/z 240, m/z 282, m/z 224 and three m/z 264s) in a full mass scan or total ion current chromatogram (TIC, Figure 2C), respectively. An extracted ion current chromatogram (EIC, Figure 2D) gave an MS profile similar to the ESR chromatogram (Figure 2B) when the above protonated molecular ions were selected. Assignments of all ESR-active peaks in Figure 2B were made following the LC/MS2 analysis consistent with the proposed mechanism (Scheme 1).

Figure 2.

On-line LC/ESR and LC/MS chromatograms of enzyme-free condensed sample mixture from the experiment of Figure 1A. (A) UV chromatographic separation was performed at absorption of 265 nm with a C18 column (ZORBAX Eclipse-XDB, 3.0 × 75 mm, 3.5 μm) equilibrated with solvent A (H2O-0.1% HOAc). Conditions of gradient elution were described in Methods; (B) ESR chromatogram was obtained in an ESR spectrometer equipped with an Aquax ESR cell. A time scan was performed with the magnetic field fixed on the maximum of the first line of Figure 1A. There was a 9 s offset due to the connection between UV detection and ESR detection. On-line ESR settings were described in Methods; (C) On-line MS (full scan or total ion current chromatogram, TIC, m/z 150 to m/z 600) was obtained with chromatographic conditions identical to those in on-line ESR. The LC flow rate (0.8 mL/min) was adjusted to 30–40 μl/min into the MS inlet with a splitter; the first 2 min of LC eluants were always bypassed and not analysed for their MS. There was a 35 s delay between UV and MS measurement. MS settings were described in Methods; (D) Extracted ion current chromatogram (EIC) of four ions (m/z 240, m/z 282, m/z 224 and m/z 264) from the above full scan was obtained for the MS profile matching the POBN trapped radicals that were monitored as ESR-active peaks in on-line ESR. ‘×’: the second EIC peak of the m/z 282 that was a radical-unrelated product since no corresponding on-line ESR peak was observed in B.

The ESR chromatogram peak 2 and the related EIC peak (tR≈9.6 min, m/z 240, Figures 2B and D) most likely corresponded to the POBN adduct of hydroxyethyl radical (•C2H4OH). This radical, formed from ethanol oxidation, occurred in the EPA system because ethanol was used to prepare EPA stock solutions. The LC/MS2 spectrum of the m/z 240 ion (Figure 3A) in ESR peak 2 was consistent with the fragmentation pattern of POBN/•C2H4OH published elsewhere [27–29] and thus confirmed the assignment of this structure.

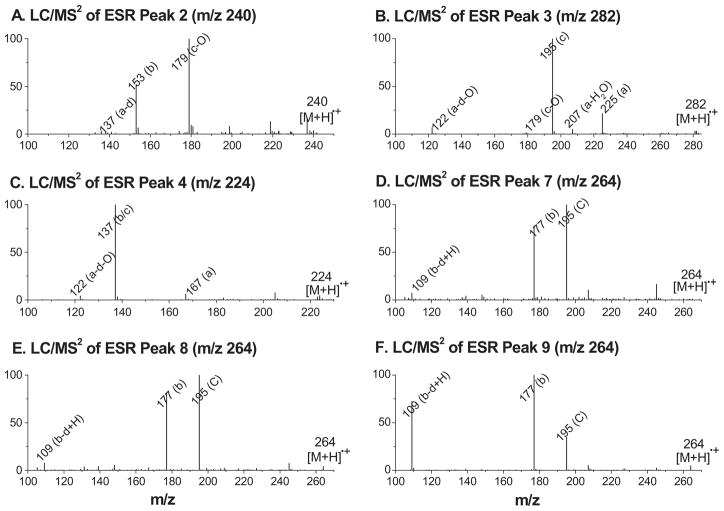

Figure 3.

LC/MS2 spectra of selected POBN adducts that were shown as ESR peaks in Figure 2B. (A) LC/MS2 of m/z 240 ion for on-line ESR peak 2; (B) LC/MS2 of m/z 282 ion for on-line ESR peak 3; (C) LC/MS2 of m/z 224 for on-line ESR peak 4; (D) LC/MS2 of m/z 264 ion for on-line ESR peak 7; (E) LC/MS2 of m/z 264 ion for on-line ESR peak 8; (F) LC/MS2 of m/z 264 ion for on-line ESR peak 9. Note that fragmentation patterns and a, b, c and d ions of all tested POBN adducts were consistent with the LC/MS2 of POBN adducts published elsewhere [27,28] as well as the pattern described in Scheme 1.

The ESR chromatogram peak 3 and the related EIC peak (tR≈10.5 min, m/z 282, Figures 2B and D) appear to correspond to the POBN adduct of the propionyloxyl radical (•C4H7O2) that was generated from β-scission of the 5-EPA-alkoxyl radical (Scheme 1). This assignment was confirmed by its LC/MS2 (Figure 3B), which showed the main fragmentation ions of POBN/•C4H7O2 [28].

The ESR chromatogram peak 4 and its EIC peak (tR≈12.2 min, m/z 224, Figures 2B and D) could be assigned to the POBN adduct of the ethyl radical (•C2H5) that was generated from β-scission of the 18-EPA-alkoxyl radical (Scheme 1). The LC/MS2 spectrum of the m/z 224 in peak 4 (Figure 3C) showed fragmentation patterns that were consistent with the assignment of POBN/•C2H5 as published elsewhere [27].

The ESR chromatogram peaks 7–9 and their EIC peaks (tR≈18.6, 18.8 and 19.9 min, m/z 264s, Figures 2B and D) appeared to be the three isomers of the POBN adduct of pentenyl radical (•C5H9). Pentenyl radical can be formed from β-scission of the 15-EPA-alkoxyl radical (Scheme 1). Unlike the three well-separated m/z 264 isomers observed in previous studies [27], here two small isomeric peaks overlapped almost completely (tR≈18.6 and 18.8 min) due to the different chromatographic conditions in this study. The LC/MS2 spectra of the m/z 264 ions in ESR peaks 7–9 are shown in Figures 3D–F, respectively. Although the main fragmentation ions of POBN/•C5H9 were consistent with their structural assignments, the nearly identical LC/MS2 spectra of the m/z 264 ions in ESR peaks 7–9 did not provide enough information to differentiate among the isomers.

The EIC peak (tR≈17.9 min) marked by ‘X’ in Figure 2D was also profiled as m/z 282; however, it was completely unrelated to POBN/•C4H7O2, whose ESR-active fraction was seen at tR≈10.5 min. In addition to the absence of a matching ESR peak in Figure 2B, the LC/MS2 analysis of this m/z 282 fraction provided more convincing evidence that it was not a POBN adduct, as the distinct fragmentation pattern of the POBN adduct (e.g. a, b, c, and d ion, Scheme 1) was not detected (data not shown). In fact, this product was also formed and separated in the reaction system excluding POBN.

There were other ESR-active products, such as the ESR chromatogram peaks 1, 5–6 and 10–11 (Figure 1B) that were much more difficult to match with their protonated molecular ions, since no matching sets of peaks were found among on-line UV, on-line ESR and on-line MS (Figures 2A–C). This phenomenon often occurs when adducts of very low abundance are co-eluted with other major components. For example, the chance to profile or extract possible molecules for ESR peak 1 (tR≈7.3 min) was completely lost when the dominant m/z 195 ion was co-eluted due to the necessary overdose of the POBN spin trap.

Indeed, to distinguish limited amounts of different radical adducts from the large POBN peak (m/z 195, tR 6.8–8 min) represents a challenge in LC/MS. According to our previous observations, all peaks (e.g. peak 1 from the on-line ESR) that co-eluted with POBN very likely corresponded to the isomers of POBN adducts of dihydroxylinolenic acid radical •L(OH)2, polar radicals that form during the LOX-catalysd peroxidation of many PUFAs [27,28]. To test for this possibility in EPA peroxidation (Scheme 1), a D9-POBN spin trapping experiment was also conducted for the same LOX-catalysed system. Solid evidence for the above assignment was provided by the similarity of fragmentation patterns in the LC/MS2 spectra for the m/z 530 ion at tR≈7.3 min (Figure 4A, the POBN adduct of EPA-dihydroxyl radical) and for the m/z 539 ion (Figure 4B, the D9-POBN adduct of EPA-dihydroxyl radical).

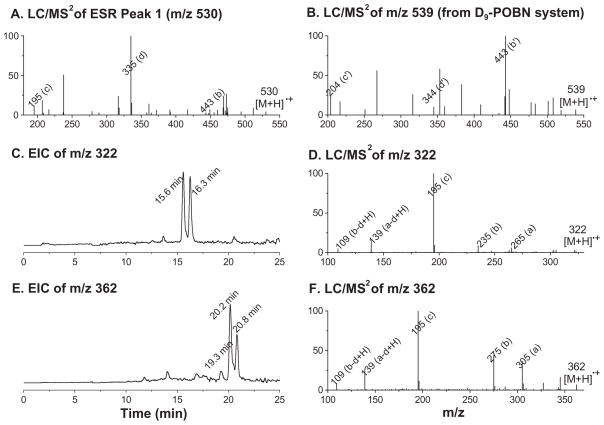

Figure 4.

LC/MS2 and EICs of additional POBN adducts that were shown as ESR peaks in Figure 2B. (A, B) LC/MS2 spectra of on-line ESR peak 1 (m/z 530, POBN/•L(OH)2) and m/z 539 ion from the D9-POBN experiment relevant to on-line ESR peak 1 in Figure 2B. The D9-POBN-related product always has retention times ~12 s shorter than its POBN counterpart under our chromatography conditions. Some unique characteristics were observed for each associated pair of POBN vs D9-POBN experiments due to fragmentations with/without the loss of the tert-butyl group (b′ and c′ ion); (C, D) EIC and LC/MS2 of m/z 322 for two isomers of POBN/•C7H11O2 at tR ≈15.6 and 16.3 min; (E, F) EIC and LC/MS2 of m/z 362 for three isomers of POBN/•C10H15O2 at tR ≈19.3, 20.2 and 20.8 min. Note that the fragmentation patterns and a, b, c and d ions of all tested POBN adducts were consistent with the pattern described in Scheme 1.

Among many structural possibilities in the proposed mechanism (Scheme 1), there were two radical adducts (POBN/•C7H11O2 and POBN/•C10H15O2) with protonated molecular ions of m/z 322 and 362 that appeared to correspond to the remaining ESR peaks (5–6 and 10–11). Such radicals are generated from β-scission of 8-EPA-alkoxyl radical (•C7H11O2) and 11-EPA-alkoxyl radical (•C10H15O2), respectively. As shown in the EIC (Figure 4C), two isomers of POBN/•C7H11O2 (m/z 322) most likely corresponded to ESR peaks 5–6 at retention times of 15.6 and 16.3 min. The subsequent LC/MS2 of the m/z 322 ions for these peaks provided convincing evidence of this assignment in the form of the consistent fragmentation pattern of POBN/•C7H11O2 (a, b, c and d ion, Figure 4D), although there was not enough evidence to distinguish between the two relevant isomers (data not shown). Similarly, the structures of ESR peaks 10–11 were assigned to two larger isomers of POBN/•C10H15O2 at tR≈20.2 and 20.8 min based on the corresponding EIC and LC/MS2 of m/z 362 (Figures 4E and F). An additional small fraction also extracted was a third isomer of POBN/•C10H15O2 (tR≈19.3 min in Figure 4E), which was overlapped by the most abundant isomer of m/z 264, ESR peak 9, in Figures 2C and D. However, again, there was not enough detail from the LC/MS2 analysis of those fractions to distinguish between the relevant isomers.

For the above two assignments, each chromatographic fraction with m/z 322 or m/z 362 in the POBN experiment had a counterpart in the D9-POBN spin trapping experiment whose EIC and LC/MS2 further verified their respective assignments (data not shown).

LC/MS study of ESR-silent products: Identification of redox forms of POBN adducts

Free radicals, including radical adducts, can be either reduced or oxidized during the system’s reaction depending on the local redox environment. Under our reaction conditions, the ESR-active forms of POBN radical adducts could be converted to two ESR-silent redox forms of POBN adducts, namely the hydroxylamine and nitrone adducts (Scheme 1). The reduction and oxidation of any given POBN adduct corresponded to the structural changes within ±1 Da for the protonated molecules during MS ionization (Scheme 1).

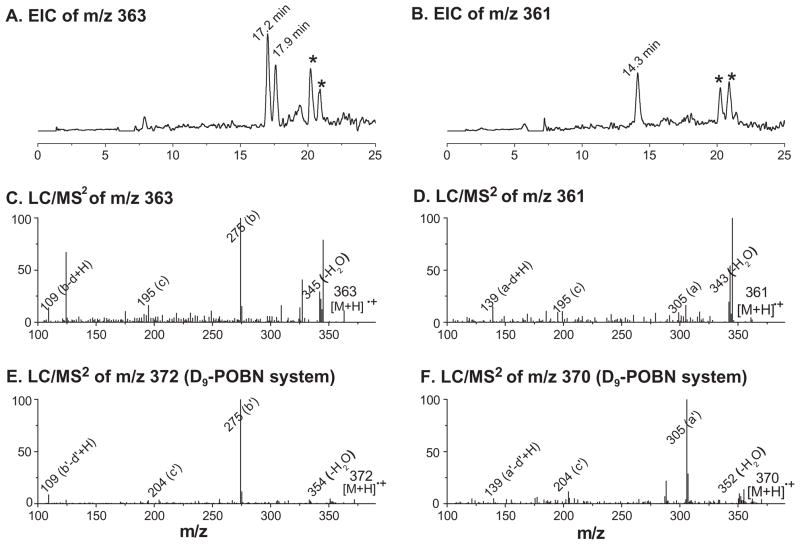

For example, when the EICs of m/z 363 and m/z 361 of control experiments excluding POBN (-POBN, data not shown) were subtracted individually from those of the complete EPA-peroxidation experiments to eliminate fault redox forms of POBN/•C10H15O2, two possible isomers of the reduced form of such an adduct were observed as EIC peaks of m/z 363 at tR≈17.2 and 17.9 min (Figure 5A), while only one oxidized product (or more than one, but not separated under our conditions) was profiled at tR≈14.3 min (Figure 5B). LC/MS2 studies from POBN spin trapping experiments confirmed these assignments by showing unique fragmentation patterns of m/z 363 and m/z 361 ions in Figures 5C and D, respectively. Subsequent LC/MS2 analysis of m/z 372 and m/z 370 from D9-POBN experiments further verified the assignments (Figures 5E and F).

Figure 5.

EICs and LC/MS2 of ESR-silent forms of POBN adducts of •C7H11O2. (A, B) EICs of m/z 363 and m/z 361 ions as the reduced and oxidized forms of POBN/•C7H11O2. The ‘★’ marked EIC peaks represent the portion of the ESR-active form(s) being reduced/oxidized during MS ionization, while the ‘×’ marked EIC peak represents a radical-unrelated product; (C, D) LC/MS2 of m/z 363 and 361 ions as the reduced and oxidized forms of POBN/•C7H11O2, respectively; (E, F) LC/MS2 of m/z 372 and 370 ions from the D9-POBN experiment equivalent to (C) and (D). Note that a D9-POBN-related product always has retention times ~12 s shorter than its POBN counterpart under our chromatography conditions. Some unique characteristics were observed for each associated pair of POBN vs D9-POBN experiments due to fragmentation with/without the loss of the tert-butyl group (b′ and c′ ion). Note that the EIC of (A) and (B) are actually the computer-subtracted chromatogram of the EIC of the complete reaction minus that of the -POBN control reaction (to eliminate radical-unrelated EIC peaks).

Similarly, ESR-silent products of other identified POBN adducts in Figures 2–4 could all be structurally assigned from their EIC and LC/MS2, as listed in Table I. Note that more isomers for some ESR-silent adducts were possible than for the original adduct due to the different positions available to be protonated (for reduction) or the formation of geometric isomers from the newly formed double bond (for oxidation), respectively.

Table I.

Retention times, protonated molecular ions and major fragmentation ions observed from LC/MS2 analysis of ESR-silent redox forms of EPA-derived radical adducts.

| Radical adducts POBN/•R | Redox form | Mw (m/z) | ★tR (min) |

† Fragments (m/z) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b–d | a–d–O | a–d | c–O | c | b | a | -CO2 | -H2O | -C3H8 | ||||

| POBN/•C10H15O2 | Ox | 361 | 14.3 | 139 | 195 | 305 | 317 | 345‡ | |||||

| Red | 363 | 17.2, 17.9 | 109 | 195‡ | 274 | 345 | |||||||

| POBN/•C2H5 | Ox | 223 | 5.7, 10.8 | 122 | 179 | 195 | 167‡ | ||||||

| Red | 225 | 6.7 | 195 | 205‡ | |||||||||

| POBN/•C5H9 | Ox | 263 | 22.0 | 179 | 195 | 207‡ | 245 | ||||||

| Red | 265 | 14.9 | 137 | 195 | 207 | 221‡ | |||||||

| POBN/•C4H7O2 | Ox | 281 | 6.3 | 123 | 195 | 237 | 263‡ | ||||||

| Red | 283 | 6.7, 14.3 | 109 | 179 | 195‡ | 225 | 239 | 265 | |||||

| POBN/•C7H11O2 | Ox | 321 | 27.7 | 179‡ | 195 | ||||||||

| Red | 323 | 12.4, 12.6 | 109 | 124‡ | 235 | 263 | 302 | ||||||

| POBN/•L(OH)2 | Ox | 529 | 20.5 | 195 | 473‡ | ||||||||

| Red | 531 | 6.3 | 195‡ | 443 | 473 | ||||||||

Only retention times of radical-related products are listed in this table because these product ions (peaks) are all observed in the computer-subtracted EIC from ± POBN experiments, e.g. Figures 5A and B. These radical-related molecules are also verified from their D9-POBN experiments. Note, without subtracting -POBN experiment, some fault redox forms (radical unrelated molecules) could also be observed as the relevant EIC peaks, e.g. m/z 363 at tR 7.5 min; m/z 223 at tR 21.2 min; m/z 225 at tRs 10.2 and 10.6 min; m/z 263 at tRs 14.1, 18.1 and 26.5 min; m/z 265 at tR 16.6 min; m/z 281 and 283 at tR 18.1 min; m/z 321 at tR 23.9 min; and m/z 323 at tR 24.7 min.

Note that fragmentation patterns and a, b, c, and d ions of all tested POBN adducts were consistent with the LC/MS2 of POBN adducts published elsewhere [27,28,30] as well as the pattern described in Scheme 1.

Marked fragmentation ions represent the base peak of each product during MS2 analysis.

Note, the redox forms of the m/z 240 ion (m/z 241 and m/z 239) were not analysed because they are EPA-unrelated radicals.

LC/MS comprehensive quantification of spin-trapped radicals

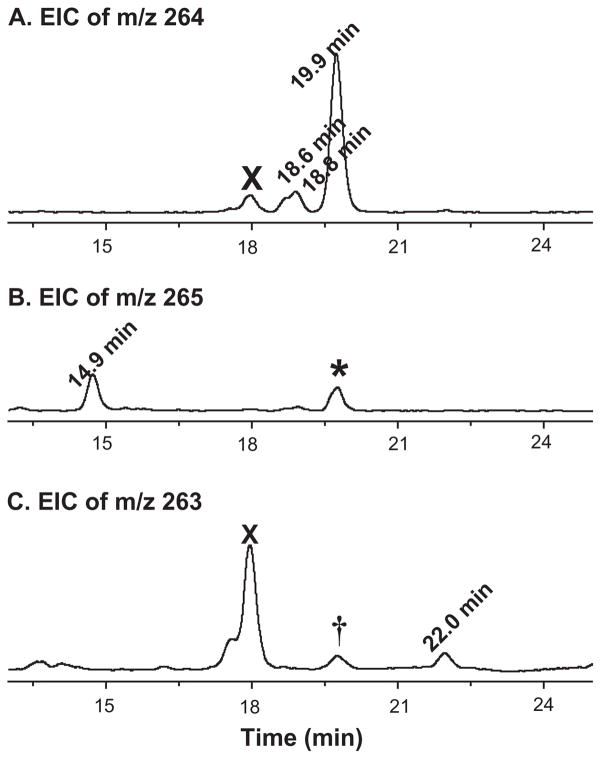

Quantification of free radical formation is critical for evaluation and interpretation of many radical-mediated biological processes. Our high throughput LC/MS analysis allowed us to simultaneously identify all three redox forms of each POBN trapped radical [30,35]. It has now been refined and extended to a high throughput LC/MS screen for a comprehensive quantification of each free radical’s formation, with D9-POBN used as an internal quantitative standard rather than a spin trap for radical identification. For this purpose, 2.0 μg/mL D9-POBN was added as internal standard after the analyte was mixed with ACN (to denature and precipitate LOX enzyme and thereby stop radical generation) for quantifying three redox forms of all POBN adducts (e.g. peaks labelled with retention time in EICs of Figure 6 and Tables I and II). Note that during an MS ionization, POBN adducts also readily convert to other redox forms. For instance, due to the ongoing redox reactions inside the MS source, a portion of POBN/•C5H9 (m/z 264) was detected as both the oxidized form (m/z 263 ion, marked with † in Figure 6C) at tR≈19.9 min and the reduced form (m/z 265 ion, marked with an asterisk in Figure 6B) although m/z 265 ion might also result from isotopic contribution. To comprehensively but not doubly count the quantity of POBN adduct of •C5H9, we include all redox forms generated both during the system reaction and inside the MS source by subtracting 16.6% (isotopic contribution) of total amount of POBN/•C5H9 at 19.9 min (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Comprehensive quantification of POBN/•C5H9 via LC/MS with an internal standard (I.S.) of 2.0 μg/mL D9-POBN. (A) EIC abundance of m/z 264 ion (ESR-active form of POBN/•C5H9) at tR ≈18.6, 18.8, and 19.9 min; (B) EIC abundance of m/z 265 ion as the reduced form of POBN/•C5H9 at tR ≈14.9 min, as well as asterisked peak at tR ≈19.9 min (generated from m/z 264 ion due to MS ionization as well as isotopic contribution); and (C) EIC abundance of m/z 263 ion (oxidized forms of POBN/•C5H9) at tR ≈22.0 min and peak marked by ‘†’ at tR ≈19.9 min (generated from m/z 264 ion due to MS ionization). EIC peaks marked ‘X’ represent radical-unrelated products. Quantanalysis version 1.8 for Agilent 6300 Series Ion trap LC/MS was used to process the integration and calculation.

Table II.

Relative quantification of each POBN adduct in all three redox forms formed from LOX-catalysed EPA peroxidation.

| Reaction Time (min) |

POBN/•C5H9 |

POBN/•C2H5 |

POBN/•C4H7O2 |

POBN/•C7H11O2 |

POBN/•C10H15O2 |

ξ POBN/•L(OH)2 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ox★ m/z 263 |

Rad† m/z 264 |

Red‡ m/z 265 |

Ox★ m/z 223 |

Rad† m/z 224 |

Red‡ m/z 225 |

Ox★ m/z 281 |

Rad† m/z 282 |

Red‡ m/z 283 |

Ox★ m/z 321 |

Rad† m/z 322 |

Red‡ m/z 323 |

Ox★ m/z 361 |

Rad† m/z 362 |

Red‡ m/z 363 |

Ox★ m/z 529 |

|

| 0.5 | 0.26± 0.03 | 1.75± 0.13 | 0.12± 0.01 | 0.00± 0.00 | 0.09± 0.00 | 0.09± 0.0 | 0.00± 0.00 | 0.04± 0.00 | 0.03± 0.01 | 0.12± 0.00 | 0.04± 0.00 | 0.00± 0.00 | 0.00± 0.00 | 0.02± 0.00 | 0.09± 0.05 | 0.00±0.00 |

| 1 | 0.33± 0.02 | 2.33± 0.28 | 0.14± 0.02 | 0.18± 0.05 | 0.20± 0.03 | 0.11± 0.01 | 0.00± 0.00 | 0.09± 0.01 | 0.05± 0.00 | 0.18± 0.01 | 0.06± 0.01 | 0.02± 0.00 | 0.00± 0.00 | 0.04± 0.00 | 0.18± 0.02 | 0.01±0.00 |

| 2 | 0.48± 0.05 | 3.18± 0.16 | 0.22± 0.03 | 0.30± 0.04 | 0.24± 0.01 | 0.11± 0.00 | 0.04± 0.00 | 0.11± 0.00 | 0.05± 0.01 | 0.32± 0.04 | 0.08± 0.01 | 0.03± 0.00 | 0.00± 0.00 | 0.07± 0.01 | 0.21± 0.07 | 0.03±0.00 |

| 5 | 1.03± 0.15 | 6.54± 1.43 | 0.66± 0.11 | 1.07± 0.13 | 1.13± 0.19 | 0.38± 0.05 | 0.13± 0.02 | 0.37± 0.07 | 0.15± 0.03 | 0.76± 0.12 | 0.07± 0.01 | 0.06± 0.01 | 0. 07± 0.03 | 0. 01± 0.00 | 0.36± 0.20 | 0.04±0.00 |

| 15 | 1.28± 0.22 | 7.79± 1.06 | 1.60± 0.15 | 1.06± 0.20 | 0.82± 0.15 | 0.24± 0.04 | 0.17± 0.05 | 0.37± 0.06 | 0.10± 0.02 | 0.87± 0.13 | 0.19± 0.03 | 0.14± 0.03 | 0.06± 0.02 | 0.15± 0.02 | 0.31± 0.10 | 0.12±0.02 |

| 30 | 0.90± 0.03 | 5.51± 1.31 | 0.51± 0.08 | 1.43± 0.10 | 1.68± 0.05 | 0.38± 0.07 | 0.17± 0.01 | 0.54± 0.03 | 0.10± 0.00 | 0.54± 0.03 | 0.07± 0.01 | 0.05± 0.00 | 0.03± 0.01 | 0.01± 0.00 | 0.51± 0.02 | 0.04±0.01 |

| 45 | 0.87± 0.14 | 5.04± 0.67 | 0.46± 0.14 | 1.65± 0.37 | 1.92± 0.28 | 0.36± 0.08 | 0.21± 0.04 | 0.59± 0.10 | 0.10± 0.03 | 0.60± 0.09 | 0.09± 0.02 | 0.08± 0.01 | 0.10± 0.03 | 0.01± 0.00 | 0.57± 0.32 | 0.06±0.03 |

| 60 | 1.10± 0.03 | 9.18± 1.04 | 0.80± 0.09 | 2.74± 0.27 | 3.15± 0.22 | 0.55± 0.05 | 0.40± 0.06 | 1.05± 0.11 | 0.15± 0.02 | 0.69± 0.03 | 0.14± 0.03 | 0.17± 0.01 | 0.08± 0.03 | 0.01± 0.00 | 0.59± 0.23 | 0.24±0.07 |

Oxidized forms of POBN radical adducts, e.g. nitrone adducts, are structural analogues of nitrone compounds (spin trap POBN as well as its isotope-substitute D9-POBN). Thus, oxidized forms of POBN radical adducts are directly quantified (1:1) in the absolute concentration unit when D9-POBN (2.0 μg/ml) was used as internal standard.

The different ionization efficiencies among the redox forms of POBN adduct are measured and calculated using an LOX-catalysed linoleic acid peroxidation as a model system where two main POBN adducts (POBN/•C8H15O2 and POBN/•C5H11) are formed and their reduced forms can also be obtained following the reaction with a large amount of ascorbic acid. Under our experiment condition, by comparing MS efficiencies for the above two POBN radical adducts and their reduced forms toward to D9-POBN (2.0 μg/mL, internal standard), we defined response factors of D9-POBN (standard) vs POBN radical adduct vs reduced adduct forms as 1:2.05:2.87. Thus, those values were used to normalize original MS peak area, e.g. peaks in Figure 6, for data in the Table.

spin adduct as well as the reduced form failed to produce reliable statistical data, both due to overlap with the necessary overdose of POBN.

Note, the ESR-active peak 2, m/z 240 for POBN/•C2H4OH, was not listed since it was not an EPA-related radical product and has been characterized in many previous studies. Quantanalysis version 1.8 for Agilent 6300 Series Ion trap LC/MS was used to process the integration and calculation. Data are expressed as means ± SD from n≥3.

In addition, considering possibly different ionization efficiencies among three redox forms of POBN adducts, we directly calculated oxidized forms of all POBN radical adducts (D9-POBN structural analogue) with MS response factor 1:1 in absolute concentration units (μg/mL), while concentration of POBN radical adduct and adduct reduced forms have been calculated in concentration units (μg/mL) by considering their MS response factors (1:2.05 and 1:2.87, respectively) toward internal standard D9-POBN (2.0 μg/mL Table II). With consideration of isotopic contribution, the redox forms of each POBN adduct in LOX-catalysed EPA peroxidation are comprehensively quantified as listed in Table II. This experiment represents the first comprehensive quantification of the radicals produced from EPA peroxidation in both their long-lived ESR active forms and their oxidized or reduced ESR inactive forms.

Discussion

Increased evidence from recent animal and in vitro cellular research indicates that the metabolism of EPA can inhibit carcinogenesis in many cancers. Free radical-mediated peroxidation is one of many possible mechanisms to which EPA’s anti-cancer activity has been attributed. However, even though they are the most reactive intermediates in its peroxidation, EPA-derived radicals have previously received no attention for their possible anti-cancer activities due to the lack of an appropriate method to measure them directly. Although the ESR spin trapping technique is a unique tool for studying radical mechanism of in vitro or in vivo lipid peroxidation [21–26], its impact is very restricted by two inherent limitations: (1) spin trapped radicals, e.g. POBN adducts, can’t be identified in detail since many radicals share identical or nearly identical ESR spectra; and (2) detection sensitivity is extremely low since in vivo radical adducts are mostly reduced or oxidized to ESR-silent forms, hydroxylamine and nitrone adduct due to the presence of numerous reducing or oxidizing agents in cellular or living systems.

In this work we have used the combination technique of LC/ESR and LC/MS to comprehensively profile the spin adducts of carbon-centred radicals formed from soybean lipoxygenase-catalysed EPA peroxidation in the presence of POBN. Two classes of EPA-derived radicals (Scheme 1) were identified as ESR-active forms: lipid dihydroxyallylic radicals (•L(OH)2) and a variety of radicals formed from β-scission of lipid alkoxyl radicals (stemmed from the Fenton-type reactions of the relevant LOOHs, Scheme 1). The free radicals that stem from β-scission of 5-, 15- and 18-EPA-alkoxyl radicals were observed as three major products in the order •C5H9 > •C2H5 > •C4H7O2, while the radicals stemming from β-scission of 8- and 11-EPA-alkoxyl radicals were two minor products, •C7H11O2 and •C10H15O2. In addition to identifying ESR-active forms of each radical adduct by LC/ESR, ESR-silent forms of each adduct have also been identified in subsequent LC/MS analysis. By means of an internal standard in LC/MS, we have also quantified each radical adduct in all its redox forms. The additional ability to profile ESR-silent forms of radical adducts greatly improves the sensitivity and reliability of radical detection and creates a new approach for our ongoing investigation of EPA peroxidation and its associated bioactivities.

During a 1-h reaction, the overall free radical profiles did not show significant changes in our in vitro system, as most of the LOX-catalysed radical reaction appears to occur within the first 45 s, during which time > 90% of the oxygen was consumed in the reaction solution (data not shown). When pH 8.7 buffer solution (with optimized LOX activity) or higher concentrations of POBN (>80 mM) were substituted for our previous conditions [27,28], two additional classes of radicals were also detected: the EPA alkyl radical and epoxyallylic radicals (data not shown).

When the chromatographic fraction of a radical adduct and/or its redox forms is low, it normally results in a poor quality LC/MS2 spectrum, whose fragmentation pattern sometimes fails to contain enough information to confirm the proposed structure. In this case, LC/MS2 coupled with a combination of POBN and D9-POBN spin trapping experiments offers a unique and powerful identification strategy for such structural confirmation [30,34,35]. For any given trapped radical, the observation of identical LC/MS2 fragmentation patterns for both a POBN and a D9-POBN adduct confirms the structure even with poor quality MS spectra. For example, identical fragments caused by losing a radical (•R) from POBN and D9-POBN adducts (9-Da difference between their protonated molecules) leads to the observation of pair(s) of fragment ions differing by 9 Da, such as m/z 195 (c ion) and m/z 204 (c′ ion) as POBN and D9-POBN fragments, respectively (Figures 4A, B, 5C and F). Other unique pairs always observed include those involving the loss of the tert-butyl groups of POBN, i.e. a and b vs a′ and b′ ions (where hydrogen was replaced by deuterium in D9-POBN). In addition, each counterpart of a given D9-POBN-trapped radical or related derivative had a retention time ~12 s shorter than that of the corresponding POBN product under our separation conditions. All of these features make this analysis extremely valuable for structural identification of all redox forms of POBN adducts.

The reliability of traditional ESR quantification protocols, whether internal or external, has always been suspect since a structurally different standard compound must be used. In addition, when radical measurement must be followed with sample handling, e.g. lipid extraction procedure, chromatographic separation or even simple dilution/condensation with an organic solvent for enzyme precipitation, additional problems are introduced; it is then impossible to accomplish radical quantification with any type of ESR standard or protocol appropriately. Based on our observations, although all redox forms of the radical adduct most likely share a common moiety (the nitrone attached to the pyridyl ring) with POBN as the preferred position for protonation during MS ionization (Scheme 1), they have different MS efficiencies [37–38], most likely in the order of reduced form > radical form > oxidized form (2.87:2.05:1) under our experiment condition. As a POBN structural analogue, however, oxidized form of POBN radical adduct would directly be quantified (1:1) with internal standard D9-POBN in absolute concentration unit, while other redox forms, e.g. radical form and reduced form, would more appropriately be normalized with their relative response factors (calculated from the experiments of a model system described in footnote of Table II). In addition, reliable quantification of radical formation should take into account all its redox forms generated not only during the system reaction, but also during MS ionization. Under our condition, since negligible changes of MS spectra with solvent condition were also observed for all tested compounds under HPLC gradient composition of 10–70% ACN, it is no doubt that our protocol is presently the most comprehensive for quantitation of radical formation from EPA peroxidation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIEHS Grant ES-012978.

Abbreviations

- ACN

acetonitrile

- EIC

extracted ion current chromatogram

- EPA

eicosapentaenoic acid

- ESR

electron spin resonance

- HOAc

glacial acetic acid

- HPLC/LC

high performance liquid chromatography

- IS

internal standard

- LOX

lipoxygenase

- MRM

multiple reaction monitoring

- MS/MS

mass spectrometry

- POBN

α-[4-pyridyl 1-oxide]-N-tert-butyl nitrone

- PUFAs

polyunsaturated fatty acids

- TIC

total ion current chromatogram

- tR

retention time

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- 1.Sardesai VM. Nutritional role of polyunsaturated fatty acids. J Nutr Biochem. 1992;3:154–166. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henniga B, Lei W, Arzuaga X, Ghosha DD, Saraswathia V, Toborekc M. Linoleic acid induces proinflammatory events in vascular endothelial cells via activation of PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2 signaling. J Nutr Biochem. 2006;17:766–772. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.James MJ, Gibson RA, Cleland LG. Dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammatory mediator production. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:343S–348S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.1.343s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rose DP. Dietary fat, fatty acids and breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 1997;4:7–16. doi: 10.1007/BF02967049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gago-Dominguez M, Yuan JM, Sun CL, Lee HP, Yu MC. Opposing effects of dietary n-3 and n-6 fatty acids on mammary carcinogenesis: The Singapore Chinese Health Study. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1686–1692. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsuyoshi T, Igarashi M, Miyazawa T. Conjugated eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) inhibits transplanted tumor growth via membrane lipid peroxidation in nude mice. J Nutr. 2004;134:1162–1166. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.5.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leitzmann MF, Stampfer MJ, Michaud DS, Augustsson K, Colditz GC, Willett WC, Giovannucci EL. Dietary intake of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids and the risk of prostate cancer. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:204–216. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.1.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wen B, Deutsch E, Opolon P, Auperin A, Frascognal V, Connault E, Bourhis J. n-3 Polyunsaturated fatty acids decrease mucosal/epidermal reactions and enhance antitumour effect of ionising radiation with inhibition of tumour angiogenesis. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1102–1107. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuriki K, Hirose K, Wakai K, Matsuo K, Ito H, Suzuki T, Hiraki A, Saito T, Iwata H, Tatematsu M, Tajima K. Breast cancer risk and erythrocyte compositions of n-3 highly unsaturated fatty acids in Japanese. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:377–385. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolk A, Larsson SC, Johansson JE, Ekman P. Long-term fatty fish consumption and renal cell carcinoma incidence in women. JAMA. 2006;296:1371–1376. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.11.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takezaki T, Inoue M, Kataoka H, Ikeda S, Yoshida M, Ohashi Y, Tajima K, Tominaga S. Diet and lung cancer risk from a 14-year population-based prospective study in Japan: with special reference to fish consumption. Nutr Cancer. 2003;45:160–167. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC4502_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geelen A, Schouten JM, Kamphuis C, Stam BE, Burema J, Renkema JM, Bakker EJ, van’t Veer P, Kampman E. Fish consumption, n-3 fatty acids, and colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:1116–1125. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larsson SC, Kumlin M, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Wolk A. Dietary long-chain n-3 fatty acids for the prevention of cancer: a review of potential mechanisms. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:935–945. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.6.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erkkilä AT, Lichtenstein AH, Mozaffarian D, Herrington DM. Fish intake is associated with a reduced progression of coronary artery atherosclerosis in postmenopausal women with coronary artery disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:626–632. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.3.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mickleborough TD, Lindley MR, Ionescu AA, Fly AD. Protective effect of fish oil supplementation on exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in asthma. Chest. 2006;129:39–49. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanders TA. Influence of fish-oil supplements on man. Proc Nutr Soc. 1985;44:391–397. doi: 10.1079/pns19850064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kokura S, Nakagawa S, Hara T, Boku Y, Naito Y, Yoshida N, Yoshikawa T. Enhancement of lipid peroxidation and of the antitumor effect of hyperthermia upon combination with oral eicosapentaenoic acid. Cancer Lett. 2002;185:139–144. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00262-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Girotti AW. Mechanisms of lipid peroxidation. Free Radic Biol Med. 1985;1:87–95. doi: 10.1016/0748-5514(85)90011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardner HW. Oxygen radical chemistry of polyunsaturated fatty acids. Free Radic Biol Med. 1989;7:65–86. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(89)90102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janzen EG, Blackburn BJ. Detection and identification of short-lived free radicals by an electron spin resonance trapping technique. J Am Chem Soc. 1968;90:5909–5910. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janzen EG. Spin trapping. Acc Chem Res. 1971;4:31–40. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kadiiska MB, Mason RP, Dreher KL, Costa DL, Ghio AJ. In vivo evidence of free radical formation in the rat lung after exposure to an emission source air pollution particle. Chem Res Toxicol. 1997;10:1104–1108. doi: 10.1021/tx970049r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kadiiska MB, Morrow JD, Awad JA, Roberts LJ, Mason RP. Identification of free radical formation and F2-isoprostanes in vivo by acute Cr(VI) poisoning. Chem Res Toxicol. 1998;11:1516–1520. doi: 10.1021/tx980169e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qian SY, Buettner GR. Iron and dioxygen chemistry is an important route to initiation of biological free radical oxidations: an electron paramagnetic resonance spin trapping study. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26:1447–1456. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qian SY, Wang HP, Schafer FQ, Buettner GR. EPR detection of lipid-derived free radicals from PUFA, LDL, and cell oxidations. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;29:568–579. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00407-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buettner GR. Spin trapping: EPR parameters of spin adducts. Free Radic Biol Med. 1987;3:259–303. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(87)80033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qian SY, Guo Q, Mason RP. Identification of spin trapped carbon-centered radicals in soybean lipoxygenase-dependent peroxidations of ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids by LC/ESR, LC/MS, and tandem MS. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;35:33–44. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00217-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qian SY, Yue G-H, Tomer KB, Mason RP. Identification of all classes of spin trapped carbon-centered radicals in soybean lipoxygenase-dependent lipid peroxidations of ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids via LC/ESR, LC/MS, and tandem MS. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34:1017–1028. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qian SY, Tomer KB, Yue GH, Guo Q, Kadiiska MB, Mason RP. Characterization of the initial carbon-centered pentadienyl radical and subsequent radicals in lipid peroxidation: identification via on-line high performance liquid chromatography/electron spin resonance and mass spectrometry. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:998–1009. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00992-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu Q, Shan Z, Ni K, Qian SY. LC/ESR/MS study of spin trapped carbon-centered radicals formed from in vitro lipoxygenase-catalyzed peroxidation of γ-linolenic acid. Free Radic Res. 2008;42:442–455. doi: 10.1080/10715760802085344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buettner GR. In the absence of catalytic metals ascorbate does not autooxidize at pH7: ascorbate as a test for catalytic metals. J Biochem Biophys Methods. 1988;16:27–40. doi: 10.1016/0165-022x(88)90100-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Albro PW, Knecht KT, Schroeder JL, Corbett JT, Marbury D, Collins BJ, Charles J. Isolation and characterization of the initial radical adduct formed from linoleic acid and α-(4-pyridyl 1-oxide)-N-tert-butylnitrone in the presence of soybean lipoxygenase. Chem Biol Interact. 1992;82:73–89. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(92)90015-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ortiz de Montellano PR, Augusto O, Viola F, Kunze KL. Carbon radicals in the metabolism of alkyl hydrazines. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:8623–8629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qian SY, Chen YR, Deterding LJ, Fann YC, Chignell CF, Tomer KB, Mason RP. Identification of protein-derived tyrosyl radical in the reaction of cytochrome c and hydrogen peroxide: characterization by ESR spin-trapping, HPLC and MS. Biochem J. 2002;363:281–288. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3630281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qian SY, Kadiiska MB, Guo Q, Mason RP. A novel protocol to identify and quantify all spin trapped free radicals from in vitro/in vivo interaction of HO• and DMSO: LC/ESR, LC/MS, and dual spin trapping combinations. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilcox AL, Marnett LJ. Polyunsaturated fatty acid alkoxyl radicals exist as carbon-centered epoxyallylic radicals: a key step in hydroperoxide amplified lipid peroxidation. Chem Res Toxicol. 1993;6:413–416. doi: 10.1021/tx00034a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De la Mora JF, Van Berkel GJ, Enke CG, Cole RB, Martinez-Sanchez M, Fenn JB. Electrochemical processes in electrospray ionization mass spectrometry–discussion. J Mass Spectrom. 2000;35:939–952. doi: 10.1002/1096-9888(200008)35:8<939::AID-JMS36>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Metzger JO, Griep-Raming J. Electrospray ionization and atmospheric pressure ionization mass spectrometry of stable organic radicals. Eur J Mass Spectrom. 1999;5:157–163. [Google Scholar]