Abstract

Throat carriage (42.7%) of Staphylococcus aureus exceeded nasal carriage (35.0%) in 2 New York prisons. Methicillin resistance, primarily due to USA300, was high at both sites; 25% of dually colonized inmates had different strains. Strategies to reduce S. aureus transmission will need to consider the high frequency of throat colonization.

Recent studies have identified the oropharynx as a potential site of Staphylococcus aureus colonization. This colonization may occur in the presence or absence of nasal colonization [1, 2]. Oropharyngeal carriage of S. aureus has potentially important ramifications in decolonization strategies for populations at high risk of infection. Topical agents directed at eradication of nasal colonization are not likely to affect throat carriage, and as a result, reservoirs for future infection may persist.

In an earlier report, we found a high rate of nasal methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) carriage in 2 New York prisons [3]. As part of an ongoing investigation of S. aureus infection in the prison population, nasal and oropharyngeal swab samples were obtained from study participants at a men's (Sing Sing) and a women's (Bedford Hills) maximum security prison in Westchester, New York. The goal of this study was to further characterize the nature of S. aureus carriage and to determine whether oropharyngeal carriage was an important site of colonization in this population known to be at high risk of infection [4].

The Institutional Review Board of Columbia University and the New York State Department of Correctional Services reviewed and approved this study. At both facilities, the prison administration provided a list of prisoners entering the facility that week. These prisoners, located in the holding area, were privately asked whether they would like to participate and, if agreeable (72.5% at Sing Sing and 77.5% at Bedford Hills), provided written informed consent. Consecutive study participants were then interviewed, and samples from the anterior nares and oropharynx of each inmate were obtained for culture with a rayon-tipped swab (Becton Dickinson). Information collected included demographic characteristics and personal history, such as ethnicity, time spent in the prison system, medical history, and prior living conditions. This information was then verified by review of official prison medical records. Each swab sample was incubated in 6% sodium chloride–supplemented tryptic soy broth (Becton Dickinson) at 35°C overnight, to enrich S. aureus selection before being plated onto Mannitol Salt agar (Becton Dickinson) and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. Individual positive colonies were then streaked onto sheep blood agar plates before being confirmed as S. aureus with the coagulase and protein A detection kit (Murex StaphAurex) [5].

Positive samples were spa typed and compared using Ridom Staph Type software (Ridom GmbH) [6]. Positive methicillin-resistant isolates were staphylococcal chromosomal cassette mec typed using multiplex polymerase chain reaction assay, as described elsewhere [7]. Parameters for the Based Upon Repeat Pattern (BURP) clustering in the Ridom StaphType software, using standards determined by Mellman et al [8], were used to further characterize the isolates. Paired inmate samples (ie, from the nose and throat) that were identified as distinct were examined using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) with SmaI digest [5] to confirm that they were different. Settings for PFGE were as follows: initial switch time, 1.0 s; final switch time, 30.0 s; included angle, 120°; current, 6.0 V; and run time, 23 h. The buffer temperature was maintained at 12°C [5]. Strains were compared using both the Dice coefficient with a similarity rate of 80% to identify closely related strains (Bionumerics) and the Tenover criteria to examine the number of band differences between the paired strains [5, 9].

The majority of Sing Sing participants were self-described as either black (57.6%) or Latino/Hispanic (30.0%). The vast majority (95.4%) was already in the prison system and was transferred from other prisons for administrative reasons or placement at a new facility. At Bedford Hills, the majority of prisoners identified themselves as black (40.1%) or white (46.2%). In contrast with the inmates at Sing Sing, they were more likely to be transferred from the jail system (93.3%). Thus, the 2 groups of inmates reflected 2 different stages of incarceration. There were no identifiable differences in the sociodemographic data, including age, ethnicity, and prior residences, when S. aureus colonization rates were compared at the 2 prisons (Table 1).

Table 1.

Description of Inmates and Samples Collected at the 2 Prisons

| Bedford Hills (n = 312) | Sing-Sing (n = 217) | ||||

| Characteristic | |||||

| Ethnicity | Proportion positive for Staphylococcus aureus (%) | Proportion positive for S. aureus (%) | |||

| Black | 64/125 (51.2) | 82/125 (65.6) | |||

| White | 78/144 (54.2) | 13/19 (68.4) | |||

| Latino/Hispanic | 19/35 (54.3) | 44/65 (67.7) | |||

| Other | 1/8 (12.5) | 5/8 (62.5) | |||

| Residence before prison | |||||

| Different or same prison | 17 (5.4) | 207 (95.4) | |||

| Jail | 291 (93.3) | 10 (4.6) | |||

| Other (home, apartment, etc.) | 4 (1.3) | 0 (.0) | |||

| Sample site(s) positive for S. aureus | |||||

| Total individuals colonized at the nares, throat, or both sites | 162/312 (51.9) | 144/217 (66.4) | |||

| Nares | 98/312 (31.4) | 87/217 (40.1) | |||

| Throat | 126/312 (40.4) | 100/217 (46.1) | |||

| Individuals colonized at both nares and throata | 62/312 (19.9) | 43/217 (19.8) | |||

| Same spa-type | 52 (16.7) | 22 (10.1) | |||

| Related spa-type | 1 (.3) | 4 (1.8) | |||

| Different spa-type | 9 (2.9) | 17 (7.8) | |||

| MRSA positive S. aureus samples | Proportion positive for MRSAb(%) | Proportion positive for MRSAb (%) | |||

| Total individuals colonized at the nares or throat | 35/162 (21.6) | 24/144 (16.7) | |||

| Nasal | 28/98 (28.6) | 15/87 (17.2) | |||

| Throat | 27/126 (21.4) | 15/100 (15.0) | |||

| SCCmec typesc | |||||

| SCCmec I, II, and III | 8 (15.4) | 2 (6.9) | |||

| SCCmec IV & V | 37 (71.2) | 25 (86.2) | |||

| Nontypeable | 7 (13.5) | 2 (6.9) | |||

| Most prevalent spa types at the 2 prisons | |||||

| t-8/eGenomics type 1 | 8 MSSA*, 23 MRSA | 14 MSSA, 13 MRSA | |||

| t-2/eGenomics type 2 | 12 MSSA, 6 MRSA | 6 MSSA, 1 MRSA | |||

| t-216/eGenomics type | 11 MSSA | 4 MSSA, 1 MRSA | |||

MSSA, methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Dual colonization indicates a difference in spa type of the strain isolated from the nasal versus the oropharynx from a single inmate.

Staphylococcal chromosomal cassette (SCC) mec types.

Samples from 312 women and 217 men were collected during an 8-month period (November 2009 through June 2010), with >50% testing positive. There were 185 nasal and 226 oropharyngeal samples positive for S. aureus. The overall rate of carriage in the throat (226 [42.7%] of 529) exceeded that in the anterior nares (185 [35.0%] of 529; P < .01). The women at Bedford Hills had a lower combined overall nasal and oropharyngeal colonization rate than the men at Sing Sing (P = .001).

Methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) oropharyngeal (40.4% Bedford Hills and 46.1% Sing Sing) versus nasal (31.4% Bedford Hills and 40.1% Sing Sing) colonization rates at both facilities were comparable (P > .05). MRSA carriage rates at the 2 body sites were also similar. Fifty-nine (11.2%) of 529 participants in our study group were colonized with MRSA at either or both nasal and oropharyngeal sites (Table 1). The rate of MRSA carriage was similar in both nasal and throat samples (28.6% nasal and 21.4% oropharyngeal at Bedford Hills; 17.2% nasal and 15.0% oropharyngeal at Sing Sing). Ten men and 12 women were colonized with MRSA solely in the oropharynx.

One hundred forty-seven different spa types were identified. The epidemic strain USA300 (spa type t8/eGenomics type 1) was the most prevalent overall, accounting for 14.1% of the positive samples, with 22 of 58 of these isolates being methicillin susceptible [10]. USA300 and strains closely related to USA300 (as defined by BURP analysis of the spa types) accounted for 19.4% of all positive samples, again with similar nasal and oropharyngeal colonization rates (5.3% nasal and 4.8% oropharyngeal at Bedford Hills; 4.6% nasal and 4.8% oropharyngeal at Sing-Sing).

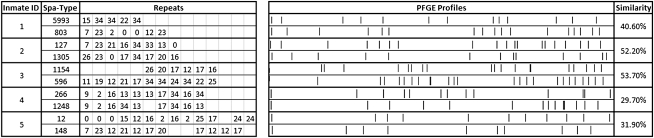

A surprising 31 (30%) of 105 individuals who tested positive at both the nasal and oropharyngeal sites had different strains, as defined by their spa types, and were classified as dually colonized. Among these were 10 persons colonized with MSSA and MRSA at the 2 sites. Samples from these inmates were compared using the repeat comparison and clustering programs (Ridom Staph Type software) to determine whether the isolates were related. Five individuals with different spa types were colonized with related spa types as determined by BURP clustering. Six (19.4%) of 31 dually colonized individuals were also MRSA positive. All paired nasal and oropharyngeal isolates identified as different by spa typing (n = 26) were further confirmed as unique with use of a separate typing technique, PFGE (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Five representative samples from dually colonized inmates that were chosen to show the differences in the Staphylococcus aureus isolate pairs. The spa types indicate the assignment of strain type based on the Ridom software. The assignment of the different repeats (allelic profile) and their location for the spa types is also provided. The PFGE profiles of the discordant pair are also displayed along with the dendrogram displaying the degree of similarity of the 2 strains. Pairwise similarity scores for the isolates were calculated using the Dice coefficient.

This study showed continued high S. aureus carriage, especially MRSA carriage, in this population known to be at high risk of S. aureus infection [3]. The study also began to address when acquisition of carriage might occur. New prison inmates, primarily transferred from jails (Bedford Hills), and prisoners transferred from other New York State correctional facilities (Sing Sing) had high carriage rates. New or prevalent community-based strains therefore appear to be regularly introduced into these facilities by inmates arriving from the community or local jails. Once introduced, the strains may persist and/or be transmitted to other inmates in the prison environment. The transfer of prisoners among different prisons, which occurs on a regular basis, may further contribute to their spread. As in our previous report, the epidemic strain t8/eGenomics type 1 (USA300) was the most prevalent strain found in both MSSA and MRSA isolates, suggesting that it is readily spread in the prison setting [3]. In light of its potential virulence, the basis for the introduction and spread of this strain in the prison system is important.

Our results showing higher throat than nasal carriage of S. aureus also confirm earlier observations that the oropharynx is an important reservoir for S. aureus [2, 11, 12]. There was no statistically significant difference in colonization rates at the 2 sites for MRSA isolates. This may not always be the case, because other investigators have speculated that, in some settings such as intensive care units, MRSA colonization of the oropharynx may not be as common [13].

Finally, the observation that individuals may be simultaneously colonized with different strains of S. aureus is of considerable interest. Nilsson and Ripa [11] noted that 3 of 39 study participants colonized with different strains had persistent carriage of these strains over 25 months. More recently, Hamdan-Partida et al [12], in addition to reporting higher throat than nares colonization in a population of healthy carriers in Mexico, found that a small percentage of dually colonized study participants had different strains in their nares and throat. In the present study, there was a relatively high rate of dually colonized inmates with different strains, suggesting that this type of colonization may be more common than was previously suspected, at least in populations at high risk of infection. These findings were validated using 2 different techniques: spa typing and PFGE.

The role of oropharyngeal colonization as a potential reservoir for future infection remains uncertain. Its frequency as a site for colonization raises questions concerning the efficacy of such topical therapies as mupirocin or chlorhexidine as prophylactic regimens. The fact that a significant minority of individuals may be colonized with different strains having different antibiotic susceptibilities, such as persons colonized with both MSSA and MRSA isolates, is also of concern. Future studies will need to address these questions in clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rachel Gordon, Anne-Catrin Uhlemann, Andrew J Lee, Superintendent Philip Heath, Superintendent Sabina Kaplan, Deputy Superintendent Marjorie Byrnes, Deputy Superintendent Kevin Winship, Deputy Superintendent Michael Capra, Dr Maryann Genovese, Dr Lori Goldstein, Dr Denise Sepe, Dr Dana Gage, Dr Bani Choudry, Margaret Franklin, Randi Uszak, Jon Hansen, and Francis Akinyombo.

Financial support. This work was supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (R01 AI082536).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: no conflicts.

References

- 1.Bignardi GE, Lowes S. MRSA screening: throat swabs are better than nose swabs. J Hosp Infect. 2009;71:373–374. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marshall C, Spelman D. Re: is throat screening necessary to detect methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization in patients upon admission to an intensive care unit? J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3855. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01176-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lowy FD, Aiello AE, Bhat M, et al. Staphylococcus aureus colonization and infection in New York State prisons. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:911–918. doi: 10.1086/520933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aiello AE, Lowy FD, Wright LN, Larson EL. Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among US prisoners and military personnel: review and recommendations for future studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:335–341. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70491-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cespedes C, Miller M, Quagliarello B, Vavagiakis P, Klein RS, Lowy FD. Differences between Staphylococcus aureus isolates from medical and nonmedical hospital personnel. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:2594–2597. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.7.2594-2597.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harmsen D, Claus H, Witte W, et al. Typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a university hospital setting by using novel software for spa repeat determination and database management. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:5442–5448. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.12.5442-5448.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milheirico C, Oliveira DC, de Lencastre H. Update to the multiplex PCR strategy for assignment of mec element types in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:3374–3377. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00275-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mellmann A, Weniger T, Berssenbrugge C, et al. Characterization of clonal relatedness among the natural population of Staphylococcus aureus strains by using spa sequence typing and the BURP (based upon repeat patterns) algorithm. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:2805–2808. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00071-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tenover FC, Arbeit RD, Goering RV, et al. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larsen AR, Goering R, Stegger M, et al. Two distinct clones of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) with the same USA300 pulsed-field gel electrophoresis profile: a potential pitfall for identification of USA300 community-associated MRSA. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:3765–3768. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00934-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nilsson P, Ripa T. Staphylococcus aureus throat colonization is more frequent than colonization in the anterior nares. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:3334–3339. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00880-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamdan-Partida A, Sainz-Espunes T, Bustos-Martinez J. Characterization and persistence of Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from the anterior nares and throats of healthy carriers in a Mexican community. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:1701–1705. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01929-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harbarth S, Schrenzel J, Renzi G, Akakpo C, Ricou B. Is throat screening necessary to detect methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization in patients upon admission to an intensive care unit? J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:1072–1073. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02121-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]