Purification and identification of endogenous polySUMO conjugates

The authors describe a rapid affinity purification procedure for the isolation of endogenous polySUMO modified proteins, which provides highly purified material suitable for individual protein studies as well as proteomic analysis.

Keywords: SUMO, polySUMO, SUMO substrates, affinity purification, mass spectrometry

Abstract

The small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) can undergo self-modification to form polymeric chains that have been implicated in cellular processes such as meiosis, genome maintenance and stress response. Investigations into the biological role of polymeric chains have been hampered by the absence of a protocol for the purification of proteins linked to SUMO chains. In this paper, we describe a rapid affinity purification procedure for the isolation of endogenous polySUMO-modified species that generates highly purified material suitable for individual protein studies and proteomic analysis. We use this approach to identify more than 300 putative polySUMO conjugates from cultured eukaryotic cells.

Introduction

Small ubiquitin-like modifiers (SUMOs) are linked by isopeptide bonds between their carboxy-terminal residue and the ɛ-amino group of a lysine side chain in the target protein. The functional consequences of SUMO modification are mostly mediated by recruitment of effector proteins that contain a SUMO interaction motif (SIM). SIMs are composed of short stretches of hydrophobic residues that directly engage the SUMO molecule (Song et al, 2004; Hecker et al, 2006). Vertebrates express three SUMO paralogues (1–3), of which both SUMO2 and SUMO3 contain a SUMO consensus modification motif (ψKxE/D) that allows the formation of polySUMO chains (Tatham et al, 2001). The ability of SUMO to form polySUMO conjugates is conserved throughout eukaryotes, and genetic studies in yeast have suggested a role for polySUMO chains in chromosome segregation, recovery from checkpoint arrest, DNA-damage response and meiosis (Bylebyl et al, 2003; Cheng et al, 2006; Schwartz et al, 2007). More recently, polySUMO chains have been shown to be recognized by proteins containing several SIMs, such as the RING-finger 4 (RNF4 or Snurf) ubiquitin E3 ligase. RNF4 contains four amino-terminal SIMs and a C-terminal RING domain that together facilitate polySUMO-specific ubiquitination (Tatham et al, 2008).

Here, we describe a procedure that uses the polySUMO-binding function of RNF4 to facilitate the specific isolation of endogenous polySUMO-modified proteins from almost any biological material in purity and yield that is suitable for high-resolution mass spectrometric analysis. We demonstrate this method by measuring changes in the polySUMOylation state of more than 300 proteins in response to heat shock.

Results

Affinity purification of polySUMO chains

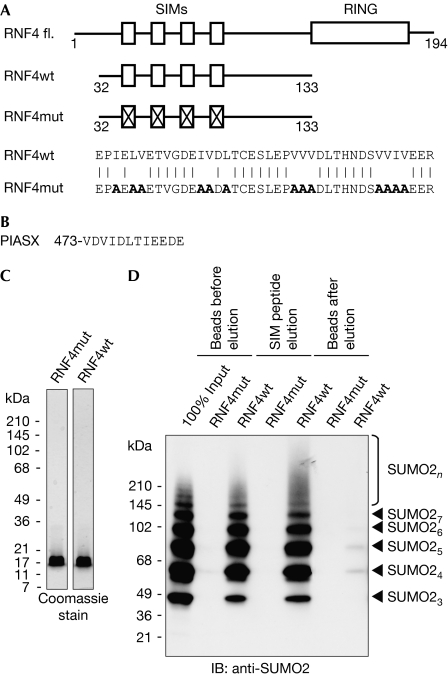

The affinity purification strategy uses a fragment of RNF4 (residues 32–133) comprising four SIMs (Fig 1A,C) that have low affinity for single SUMO moieties, but high affinity for polySUMO chains (Tatham et al, 2008). A form of RNF4 with all four SIMs mutated (RNF4mt; Fig 1A,C) is used as the negative control. Selective elution is obtained by competition with a SIM-containing peptide (Song et al, 2004) derived from the protein inhibitor of activated STATS (PIASX; Fig 1B). In vitro-generated recombinant polySUMO2 chains were efficiently bound by the RNF4 matrix, but not by the matrix linked to RNF4 with mutated SIMs. PolySUMO2 chains retained on the matrix were efficiently released by treatment with the SIM peptide, with only trace amounts of polySUMO2 chains remaining on the beads (Fig 1D). Affinity chromatography studies (supplementary Fig S1 online) show that wild-type RNF4 has SIM-dependent, preferential binding for polymers of SUMO irrespective of their linkage, compared with SUMO monomers, and shows no affinity for ubiquitin. These in vitro studies establish this method as the basis for specific purification of polySUMO conjugates.

Figure 1.

An E3 ligase inactive RNF4 fragment that binds to polySUMO. (A) Domain layout of the SUMO-dependent ubiquitin ligase RNF4. RING and SIMs are shown. Below, an RNF4 fragment from amino acids 32–133 (RNF4wt) and a SIM-mutated fragment (RNF4mut). Mutated residues are shown in bold. (B) Sequence of the SIM peptide used to elute polySUMO conjugates comprising SIM of the PIASX protein with three amino acids added at the carboxyl-terminus. (C) Purity of the RNF4 fragments was determined by SDS–PAGE. (D) Recombinant SUMO2 chains were isolated with RNF4wt and RNF4mut, followed by elution with the SIM peptide. Samples were subjected to immunoblotting with SUMO2 antibodies. IB, immunoblotting; mut, mutant; RNF4, RING-finger 4; SDS–PAGE, SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; SIM, small ubiquitin-like modifier interaction motif; SUMO, small ubiquitin-like modifier; wt, wild type.

Identification of endogenous polySUMOylated proteins

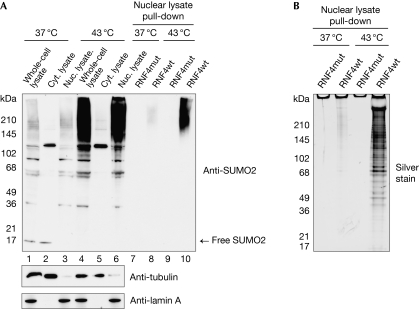

When exposed to protein-damaging stress, HeLa cells respond by enhancing SUMO2/3 conjugation (Saitoh & Hinchey, 2000), as well as polySUMO chain formation (Golebiowski et al, 2009). To preserve SUMO-modified proteins during the preparation of cytoplasmic and nuclear eukaryotic cell extracts, iodoacetamide was used to inhibit SUMO protease activities (see Methods section). Comparison between the SUMO-modified species in the nuclear extract and those from cells directly lysed under denaturing conditions showed that SUMO modification was preserved, and most of the SUMO-modified species was present in the soluble nuclear extract (Fig 2A, lanes 1–6; supplementary Fig S2A,B online). The increased quantities of SUMO conjugates triggered by heat shock were also preserved. PolySUMO conjugates from nuclear extracts were bound to RNF4 SIMs coupled to Sepharose beads and eluted from the RNF4 matrix by competition with the SIM peptide (Fig 2A, lanes 7–10). Importantly, free SUMO was not isolated, implying that individually modified proteins are not purified by this method (supplementary Fig S1 online). A silver stain of the isolated material (Fig 2B) agreed with the immunoblot analysis. To assess the extent of purification and recovery of polySUMO2 chains by this procedure, isotopically labelled recombinant, Lys 11-linked, SUMO2 dimers were ‘spiked' into the nuclear extract and RNF4-purified material. After trypsin digestion and analysis by mass spectrometry, the relative amount of Lys 11-linked SUMO chains in each fraction was calculated by reference to the isotopically labelled standard (supplementary Fig S2C online). This showed that the recovery of polySUMO chains was 80% with a 40,000-fold purification.

Figure 2.

Preservation of SUMO conjugates in nuclear and cytoplasmic fractionation. (A) HeLa cells in suspension were heat-stressed at 43°C for 1 h or control-treated at 37°C. In all, 10% of cells were lysed directly into Laemmli's sample buffer (lanes 1 and 4), with the remainder fractionated into cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts (lanes 2, 3, 5 and 6). The efficiency of fractionation and SUMO conjugates preservation was analysed by using tubulin, lamin A/C and SUMO2 antibodies (lanes 1–6). Nuclear lysates were used for purification with RNF4wt or RNF4mut crosslinked to beads. Eluates were analysed by immunoblot (lanes 7–10). Nuclear lysates represent 20% of the input for the pull-down experiments. (B) Silver-stained SDS–PAGE of the RNF4-dependent pull-downs from nuclear lysates from control and heat-stressed HeLa cells. Cyt., cytoplasmic; Nuc., nuclear; RNF4, RING-finger 4; SDS–PAGE, SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; SUMO, small ubiquitin-like modifier.

Proteomics of polySUMO conjugates after heat stress

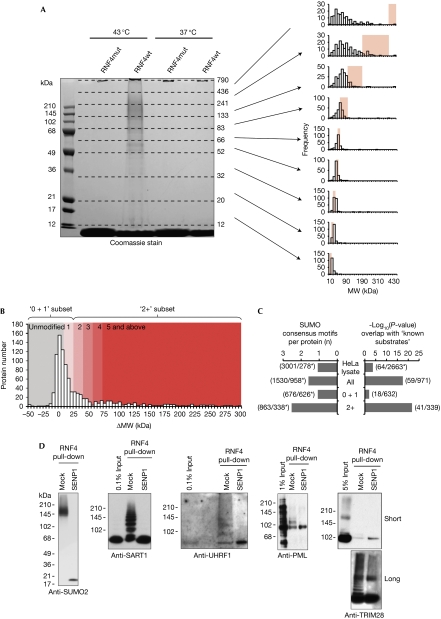

To demonstrate proteomic capability, RNF4-mediated SUMO purification was scaled up by using 375 mg of nuclear extract in each purification (Fig 3A, left panel). Isolates were subjected to in-gel digestion, followed by analysis by mass spectrometry. The success of polySUMO purification was confirmed by the identification of SUMO–SUMO branched peptides (supplementary Fig S3A–C online). After the removal of contaminants (such as trypsin and keratins), only 79 proteins were identified in the 37°C RNF4mut elution, with 95 being identified from the RNF4 wild type (RNF4wt) equivalent. Of these 95, 76 were either enriched in the wild-type condition or were not present in the mutant purification (supplementary data file 1 online). When cells were exposed to heat shock, some of the proteins identified from the RNF4mut purification approximately doubled from that of unstressed cells to 162, whereas the wild-type equivalent increased 10-fold to 979, including all 76 identified previously. A total of 828 of the 979 identified proteins had no intensity in the RNF4mut purification and 143 were more abundant in RNF4wt purification (supplementary data file 1 online). Only eight proteins were detected to approximately the same degree in both purifications. The biological relevance of these data is independently confirmed by their consistency with a previous study (Messner et al, 2009), which showed that poly-ADP ribose polymerase 1 (PARP1) is a polySUMO conjugate, the conjugation of which is stimulated by heat shock (supplementary Fig S4A online). Evidence that SUMO-modified species were being purified by this procedure was obtained by the detection of SUMO-substrate branched peptides for the previously identified proteins HNRNPM (supplementary Fig S3D online) and topoisomerase II (TOP2; supplementary Fig S3E online; Vassileva & Matunis, 2004; Azuma et al, 2005).

Figure 3.

Identification of 339 putative polySUMO conjugates after heat shock. (A) Left: Coomassie-stained SDS–PAGE gel showing the protein eluted from RNF4wt and RNF4mut purifications of polySUMO conjugates from HeLa cells grown under normal conditions (37°C) or heat-stressed (43°C) for 30 min. MW markers are shown and apparent MW boundaries of the nine slices are shown on the right. Right: Frequency histograms for the predicted MWs of all proteins found in each of the nine slices. Pink-shaded regions show the apparent MW regions of the slices. (B) Frequency histogram of the difference in molecular weight (ΔMW) between the apparent and predicted MWs of the 971 proteins binding to RNF4wt but not to RNF4mut. Coloured regions of the histogram indicate the ΔMW values consistent with unmodified proteins (grey) and those with single or several copies of SUMO molecules (red). (C) Comparison of the frequency of known SUMO substrates and the ψKxE/D SUMO conjugation consensus motifs in the indicated data sets. This comparison shows data for 2,663 proteins identified from a crude HeLa extract, along with the entire list of proteins identified in this study (971 proteins), as well as the subsets that have SUMO stoichiometry of 0 and 1 (‘0+1'; 632 proteins), or 2 or more (‘2+'; 339). Asterisks indicate lists filtered for redundancy. (D) Western blot analysis of RNF4 purifications, either mock or SENP1-treated, with indicated antibodies. mut, mutant; MW, molecular weight; PML, polymyelocytic leukaemia; RNF4, RING-finger 4; SDS–PAGE, SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; SUMO, small ubiquitin-like modifier; wt, wild type.

Identification of putative polySUMO substrates

The fact that 99% of proteins identified in RNF4wt purification from heat shock HeLa cells were enriched, in comparison with the equivalent RNF4mut sample, suggests that the purification was stringent and that more than 900 putative polySUMO conjugates were identified. However, analysis of the predicted molecular weight (MWPred) according to the amino-acid sequence of the proteins in each gel slice (Fig 3A, right) shows that many proteins in the lower five slices resolved close to their MWPred. These proteins are unlikely to be modified by SUMO and hence have been purified indirectly by association with genuine polySUMO substrates. Conversely, most of the proteins in the upper four slices resolve to molecular weights greater than their MWPred, suggesting that most of the proteins in this region are post-translationally modified.

In theory, all polySUMO conjugates will have an apparent molecular weight (MWApp) consistent with conjugation to two or more SUMOs, and therefore the difference between MWApp and MWPred can be used to filter for putative polySUMO conjugates. The MWApp of all 971 proteins specific to the RNF4wt purification from heat-shock HeLa cells was calculated (see Methods; supplementary data file 2 online), along with the difference in molecular weight (ΔMW) between MWApp and MWPred. Consistent with these observations, a large proportion of proteins resolve in the gel to a molecular weight consistent with an unmodified status, that is, ΔMW around 0 kDa (Fig 3B), and the frequency distribution is clearly skewed towards high ΔMW values (compared with equivalent data for a set of proteins not considered to be SUMOylated—supplementary Fig S5A online). By using these data, we can estimate the average number of SUMOs per substrate protein molecule, that is, the SUMOylation stoichiometry (see Methods), and by taking all proteins with ΔMW >23.7 kDa we can create a subgroup that is of an MWApp characteristic of conjugation by at least two SUMO moieties (the ‘2+' subset). Several bioinformatic analyses suggest that this method genuinely selects for SUMO conjugates. Significantly, the ‘2+' subset is enriched for proteins containing SUMO conjugation consensus motifs (Fig 3C, left), previously described SUMO substrates (Fig 3C, right) and putative SUMO2 substrates identified by an independent proteomic study (Golebiowski et al, 2009; supplementary Fig S5B,C online).

To verify the proteomic analysis, samples from RNF4 polySUMO purification were analysed by western blotting with antibodies against identified putative substrates, before and after treatment with recombinant Sentrin protease 1 (SENP1) to remove any linked SUMO. In this way, we could verify the polySUMO modification status of TRIM28 (tripartite motif-containing 28), promyelocytic leukaemia (PML), SART1 (squamous cell carcinoma antigen recognised by T cells) and UHRF1 (ubiquitin-like with PHD and RING finger domains; Fig 3D).

Biological roles of polySUMO substrates

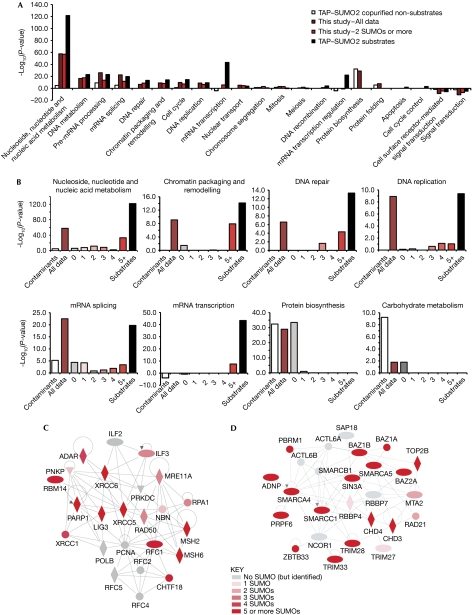

Ontological analysis of the polySUMO data obtained here (Fig 4A) shows that the results of this study agree with the tandem affinity purification (TAP)–SUMO2 heat shock proteome (Golebiowski et al, 2009), in that many proteins are involved in messenger RNA (mRNA) metabolism as well as in DNA structure, replication and repair. Owing to the TAP–SUMO2 method purified SUMO conjugates of all stoichiometries, it is suggested that proteins with these functions not only undergo increased total SUMOylation in response to heat shock, but are also targeted for polySUMOylation. Interestingly, proteins of different functions were found to be predominantly modified at specific SUMOylation stoichiometries (Fig 4B). For example, proteins involved in chromatin structure and transcription are almost exclusively modified by five or more SUMO molecules. Proteins involved in DNA replication and repair are also polySUMOylated, although they are represented in the three, four and five plus stoichiometry groups (Fig 4B–D), whereas mRNA splicing proteins are over-represented at all SUMOylation stoichiometries (Fig 4B). As this method specifically purifies polySUMO conjugates, it is suggested that many of these proteins are members of large complexes of mRNA splicing factors with different components conjugated to SUMO at different stoichiometries.

Figure 4.

Proteins involved in DNA replication and repair are polySUMOylated in response to heat stress. (A) Panther biological process gene ontology analysis of the entire data set and the ‘2+' set, and comparison with TAP–SUMO2 substrates and copurified non-substrates from Golebiowski et al (2009). (B) Same as in A, except the RNF4 purification data set is divided into six groups representing the different SUMOylation stoichiometries as indicated, and considering only the indicated gene ontology terms. (C,D) Network analysis of proteins involved in DNA repair and checkpoint control. Labels are gene names; node shapes indicate protein function: rhombus, enzyme; ellipse, transcriptional regulator; triangle, kinase; circle, other function. Lines indicate direct interactions. Nodes are coloured according to SUMOylation stoichiometry. Networks are created using ‘Ingenuity pathways analysis' (www.ingenuity.com). mRNA, messenger RNA; SUMO, small ubiquitin-like modifier.

Discussion

In the 9 years since the discovery of polySUMOylation, few substrates have been identified. Here, we use the polySUMO-binding ability of RNF4 and the specific elution by a SIM-containing peptide to purify endogenous polySUMOylated proteins from cell extracts. This results in a highly purified material that is suitable for analysis by high-resolution mass spectrometry.

So far, hypoxia-induced factor 1α (HIF1α; Matic et al, 2008), PARP1 (Martin et al, 2009), TOP2 (Takahashi & Strunnikov, 2008), proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA; Windecker & Ulrich, 2008) and the PML protein (Tatham et al, 2008) have been identified as polySUMO conjugates. In our analysis, all of these proteins except HIF1α were found, and PCNA was identified but not classified as a polySUMO substrate. These findings are not unexpected, as polySUMOylated HIF1α was detected under hypoxic conditions (Matic et al, 2008), and SUMOylation of PCNA seems to be DNA-damage dependent (Parker et al, 2008). It is interesting to note that not all polySUMOylated proteins respond to heat shock in the same way. Although the modification of PARP1 is increased by heat shock (supplementary Fig S4A online; supplementary data set 2 online), the conjugation status of PML did not change (supplementary Fig S4B online; supplementary data set 2 online). As PARP1 is the only protein now known to become polySUMOylated on heat shock (Messner et al, 2009); these findings suggest that this approach provides an accurate representation of the modification state of polySUMOylated proteins in vivo.

In addition to proteins that were nonspecifically associated with other proteins (Fig 4C,D), there were many examples of entire protein complexes being purified by RNF4, in which many members appeared not to be SUMOylated (see supplementary Fig S6 online). This reinforces the requirement for a robust data-filtering strategy when a SUMO proteome is studied under non-denaturing conditions, although it allows the study of protein complex composition.

Proteins involved in mRNA transcription or transcription regulation do not seem to become polySUMOylated on heat shock, whereas proteins involved in checkpoint response and DNA repair do (Fig 4). This is consistent with genetic studies in yeast in which deletion of the ulp 2 gene encoding the protease responsible for polySUMO chain editing results in a phenotype that includes defects in recovery from DNA-damage-checkpoint-induced cell-cycle arrest (Schwartz et al, 2007).

As SUMO–SIM interactions are conserved from yeast to vertebrates, this method should be suitable for the isolation of endogenous SUMO-modified species from any cell line or organism.

Methods

Cloning, protein expression and purification. Wild-type (RNF4wt) or SIM mutant (RNF4mut) of amino acids 32–132 of RNF4 (Tatham et al, 2008) was cloned into pHis–TEV–30a. Proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli Rosetta (DE3) cells, purified using Ni-NTA agarose, followed by the His-tag cleavage and Superdex 75 chromatography. The fragments were coupled to NHS-activated Sepharose beads.

Recombinant polySUMO and polyubiquitin pull-down. Polymers were incubated with RNF4 beads in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP40 and 0.5% deoxycholate at 4°C for 1.5 h. Beads were then washed five times with the same buffer with 250 mM NaCl and eluted as indicated.

Cell fractionation. HeLa cells were grown in suspension in Eagle's minimum essential medium containing 2 mM L-glutamine, 10% fetal calf serum and 50 U/ml penicillin and 50 μg per ml streptomycin at 37°C to a density of 8–10 × 105 cells per ml with stirring.

Cells were collected by centrifugation (500 g, 4°C, 15 min) and washed four times in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline containing 200 mM iodoacetamide. Next, the cells were incubated on ice in buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl2, 0.07% NP40, complete protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche) and 200 mM iodoacetamide) for 15 min. Cells were disrupted by dounce homogenization (40 ml dounce with tight pestle) on ice. Nuclei were collected by centrifugation (2,000 g, 4°C, 5 min). The nuclei pellet was resuspended in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP40, 0.5% deoxycholate, 200 mM iodoacetamide and protease inhibitor tablets before sonication on ice (6 × 20 s with an 18% amplitude and a large tip Branson Digital Sonifier). Nuclear extracts were centrifuged (100,000 g, 4°C, 1 h).

SUMO-conjugate isolation. A volume of 375 mg of nuclear lysate was incubated with 800 ml RNF4 beads at 4°C on a rotor for 1.5 h. The beads were washed five times with 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 250 mM NaCl, 1% NP40 and 0.5% deoxycholate, incubated with 1 μg/μl SIM peptide in the wash buffer as before and the supernatant recovered. Eluted proteins were trichloroacetic acid precipitated. The lanes containing RNF4 pull-downs were then sliced into nine sections before undergoing in-gel tryptic digestion and mass spectrometry analysis (for details on mass spectrometry and data analysis see supplementary information online).

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.emboreports.org).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Maurice (Medical Research Council Protein Phosphorylation Unit (MRC PPU), University of Dundee, UK) for sample analysis, and Chris Cole (University of Dundee, UK) for providing the tools for SUMO consensus site analysis. We thank Y. Chen (Beckman Research Institute of the City of Hope, California, USA) for advice on SIM peptide design. R.B. is funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation and by a long-term fellowship from EMBO. M.H.T. is supported by Cancer Research UK. I.M. is a Sir Henry Wellcome Postdoctoral Fellow and A.P. is a Wellcome Trust-funded PhD student.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Azuma Y, Arnaoutov A, Anan T, Dasso M (2005) PIASy mediates SUMO-2 conjugation of topoisomerase-II on mitotic chromosomes. EMBO J 24: 2172–2182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bylebyl GR, Belichenko I, Johnson ES (2003) The SUMO isopeptidase Ulp2 prevents accumulation of SUMO chains in yeast. J Biol Chem 278: 44113–44120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng CH, Lo YH, Liang SS, Ti SC, Lin FM, Yeh CH, Huang HY, Wang TF (2006) SUMO modifications control assembly of synaptonemal complex and polycomplex in meiosis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev 20: 2067–2081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golebiowski F, Matic I, Tatham MH, Cole C, Yin Y, Nakamura A, Cox J, Barton GJ, Mann M, Hay RT (2009) System-wide changes to SUMO modifications in response to heat shock. Sci Signal 2: ra24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecker CM, Rabiller M, Haglund K, Bayer P, Dikic I (2006) Specification of SUMO1- and SUMO2-interacting motifs. J Biol Chem 281: 16117–16127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin N, Schwamborn K, Schreiber V, Werner A, Guillier C, Zhang XD, Bischof O, Seeler JS, Dejean A (2009) PARP-1 transcriptional activity is regulated by sumoylation upon heat shock. EMBO J 28: 3534–3548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matic I, van Hagen M, Schimmel J, Macek B, Ogg SC, Tatham MH, Hay RT, Lamond AI, Mann M, Vertegaal AC (2008) In vivo identification of human small ubiquitin-like modifier polymerization sites by high accuracy mass spectrometry and an in vitro to in vivo strategy. Mol Cell Proteomics 7: 132–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messner S, Schuermann D, Altmeyer M, Kassner I, Schmidt D, Schar P, Muller S, Hottiger MO (2009) Sumoylation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 inhibits its acetylation and restrains transcriptional coactivator function. FASEB J 23: 3978–3989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JL, Bucceri A, Davies AA, Heidrich K, Windecker H, Ulrich HD (2008) SUMO modification of PCNA is controlled by DNA. EMBO J 27: 2422–2431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh H, Hinchey J (2000) Functional heterogeneity of small ubiquitin-related protein modifiers SUMO-1 versus SUMO-2/3. J Biol Chem 275: 6252–6258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz DC, Felberbaum R, Hochstrasser M (2007) The Ulp2 SUMO protease is required for cell division following termination of the DNA damage checkpoint. Mol Cell Biol 27: 6948–6961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Durrin LK, Wilkinson TA, Krontiris TG, Chen Y (2004) Identification of a SUMO-binding motif that recognizes SUMO-modified proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 14373–14378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Strunnikov A (2008) In vivo modeling of polysumoylation uncovers targeting of topoisomerase II to the nucleolus via optimal level of SUMO modification. Chromosoma 117: 189–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatham MH, Jaffray E, Vaughan OA, Desterro JM, Botting CH, Naismith JH, Hay RT (2001) Polymeric chains of SUMO-2 and SUMO-3 are conjugated to protein substrates by SAE1/SAE2 and Ubc9. J Biol Chem 276: 35368–35374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatham MH, Geoffroy MC, Shen L, Plechanovova A, Hattersley N, Jaffray EG, Palvimo JJ, Hay RT (2008) RNF4 is a poly-SUMO-specific E3 ubiquitin ligase required for arsenic-induced PML degradation. Nat Cell Biol 10: 538–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassileva MT, Matunis MJ (2004) SUMO modification of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins. Mol Cell Biol 24: 3623–3632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windecker H, Ulrich HD (2008) Architecture and assembly of poly-SUMO chains on PCNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Mol Biol 376: 221–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.