Abstract

This study explores community members’ perspectives regarding the relationship between neighborhood characteristics and adolescent sexual behaviors in two rural, African American communities. The data were collected as part of a community needs assessment to inform the development of HIV prevention interventions in two contiguous counties in northeastern North Carolina, USA. We conducted eleven focus groups with three population groups: adolescents and young adults aged 16–24 (N=38), adults over age 25 (N=42), and formerly incarcerated individuals (N=13). All focus groups were audio-recorded, transcribed and analyzed using a grounded theory approach to content analysis and a constant comparison method. Six major themes emerged from the discussions linking neighborhood context and adolescents sexual behavior: the overwhelming absence of recreational options for community members; lack of diverse leisure-time activities for adolescents; lack of recreational options for adolescents who are dating; adolescent access to inappropriate leisure time activities that promote multiple risk behaviors; limited safe environments for socializing; and cost-barriers to recreational activities for adolescents. In addition, lack of adequate parental supervision of adolescents’ time alone and with friends of the opposite sex, as well as ineffective community monitoring of adolescent social activities, were thought to create situations that promoted sexual and other risk behaviors. These findings allowed us to develop a conceptual model linking neighborhood structural and social organization factors to adolescent sexual behaviors and provided insights for developed interventions tailored to the local socioeconomic realities.

Keywords: Adolescent, adolescent behavior, sexual behavior, residence characteristics, rural population, USA, African-American, neighborhoods

Introduction

In the U.S., adolescent sexual activity is of tremendous public health concern because adolescents experience a disproportionate burden of adverse sexual health outcomes resulting in significant social and financial costs (CDC, 2003; Guttmacher Institute, 2006; Weinstock, Berman, & Cates, 2004). Although a substantial body of literature has explored factors that influence adolescent sexual behaviors, most focus on individual or proximal ecologic (e.g., peer, family, partner) factors. A comparatively small but growing body of literature has examined the effect of neighborhoods on adolescent sexual behaviors and reproductive outcomes (Averett, Rees, & Argys, 2002; Billy, Brewster, & Grady, 1994; Browning, Leventhal, & Brooks-Gunn, 2004; Crane, 1991; Cubbin, Santelli, Brindis, & Braveman, 2005; Hogan & Kitagawa, 1985; Jencks & Mayer, 1990; Ku, Sonnenstein, & Peck, 1993).

The role of neighborhoods in child and adolescent development derives from an ecological paradigm which views neighborhoods as part of a larger ecosystem affecting childhood development. Neighborhoods are viewed as an environment which is experienced and as an entity that can be objectively conceptualized and measured relative to health outcomes. Using this paradigm, neighborhoods have been shown to affect children’s social and health development (Brooks-Gunn, Duncan, Klebanov, & Sealand, 1993; R. L. Jarrett, 2000; Korbin & Coulton, 2000). Despite differences in study samples, study design and definitions of neighborhood, studies have generally found that children from neighborhoods characterized by socioeconomic disadvantage experience adverse health outcomes.

Neighborhood influence on adolescent sexual behaviors

In the area of reproductive health, neighborhood context has been shown to influence adolescent sexual behaviors and outcomes. Numerous measures of neighborhood context have been cited. These measures have been classified into structural or social organizational features (Browning, et al., 2004; Jencks & Mayer, 1990). Although the distinction is somewhat arbitrary, it represents an attempt to organize these measures to aid with interpreting this literature. Most studies focus on structural factors which include neighborhood characteristics such as socioeconomic status, racial composition and residential stability (Brooks-Gunn, et al., 1993; Browning, et al., 2004; Hogan & Kitagawa, 1985). Social organizational factors include the availability of community and institutional resources (e.g., family planning services, parks and recreation, libraries), measures of social disorganization (e.g., crime, joblessness, welfare dependency, school dropout), and indices of collective community social norms (e.g., teen pregnancy, early sexual behavior) (Aronowitz, Rennells, & Todd, 2006; Browning, et al., 2004; Jencks & Mayer, 1990). These studies demonstrate that in neighborhoods characterized by socioeconomic disadvantage young people have higher rates of early sexual onset, teen pregnancy, adolescent sexually transmitted infections (STI), and lower rates of adolescent condom and contraceptive use (Adimora, et al., 2001; Aronowitz, et al., 2006; Averett, et al., 2002; Billy, et al., 1994; Browning, et al., 2004; Crane, 1991; Cubbin, et al., 2005; Hogan & Kitagawa, 1985; Ku, et al., 1993).

Several mechanisms are believed to explain neighborhood effects on adolescent sexual behaviors. Neighborhoods are thought to shape the knowledge, attitudes and opportunity structures available to adolescents thereby influencing their sexual and reproductive decisions. For example, neighborhood characteristics can shape adolescents’ perceptions of the costs and benefits associated with sexual activity or teenage parenting. According to Brooks-Gunn (Brooks-Gunn, et al., 1993:page 388)”), “the nature and availability of paths for future social mobility…may influence the perceived opportunity costs of premarital sexual activity…poor economic conditions may suggest to adolescents that legitimate pathways to social mobility are closed to them, lowering the costs attached to the potential consequences of sexual activity relative to its immediate benefitsCommunity features such as poverty and unemployment may create a climate in which adolescents see few role models of economic or social success to justify the types of long term planning, such as obtaining higher education, that may encourage delayed sexual onset or contraceptive use.

Moreover, adults in disadvantaged communities may have a limited capacity to monitor adolescent’s activities or to provide access to alternative social and recreational outlets creating additional opportunities for sexual involvement (Brooks-Gunn, et al., 1993). Socially organized communities in which adults collectively supervise adolescent behaviors likely reduces adolescent risk-behaviors by supplementing the caregiver and supervisory role of parents (Brooks-Gunn, et al., 1993; Browning, et al., 2004; Elder, Eccles, Ardelt, & Lord, 1995; Kawachi & Berkman, 2000; Tesoriero, et al., 2000). This is particularly important in communities with high proportions of single-parent homes and where parents’ work hours mean children may be left home alone for several hours during the day.

Implicit social norms operating in communities are also thought to influence adolescent sexual activity. Where there are high rates of early adolescent sexual activity and teen pregnancy, particularly intergenerational teen pregnancy, adolescents may infer that the prevailing social norms favor adolescent sexual involvement. Although each of these pathways of influence is described as conceptually distinct, they are clearly linked in complex ways that ultimately shape an adolescent’s values and their behaviors.

Neighborhood Recreational opportunities and adolescent sexual behavior

The availability and utilization of neighborhood recreational opportunities by adolescents influences adolescent sexual behaviors (Browning, et al., 2004; Cubbin, et al., 2005; Elder, et al., 1995; Oman, Vesely, & Aspy, 2005). Neighborhood recreational opportunities include school-based extra-curricular programs, national organizations for adolescents, and programs in faith and community-based organizations. Most studies focus on adolescent participation in school-based extra-curricular programs. In small (Cohen, Farley, Taylor, Martin, & Schuster, 2002; Miller, Sabo, Farrell, Barnes, & Melnick, 1998) and nationally-representative samples (Miller, Sabo, Farrell, Barnes, & Melnick, 1999; Zill, Nord, & Loomis, 1995), adolescents who participated in school-based activities initiated sex at a later ages, were less likely to be currently sexually active, had fewer sexual partners, higher rates of contraceptive use, and lower rates of pregnancy and child-bearing (Cohen, et al., 2002; Miller, et al., 1998, 1999; Zill, et al., 1995).

Few studies have examined how the availability of community-based recreational opportunities affects adolescent sexual behavior (Cubbin, et al., 2005; R. Jarrett, 1997; Oman, et al., 2005). In a cross-sectional study of an ethnically mixed adolescent sample, adolescents reporting higher levels of involvement in community-based activities were less likely to initiate sex (Oman, et al., 2005). In a nationally representative sample, adolescents residing in neighborhoods with a greater concentration of ‘idle’ young people had an increased odds of sexual initiation and reduced likelihood of contraceptive use (Cubbin, et al., 2005). These studies suggest that engagement in community-based recreational activities may also reduce the likelihood of adolescent sexual behaviors and adverse sexual health outcomes.

Limitations of existing literature

There are several key limitations of existing studies of neighborhood effects on adolescent reproductive health. Neighborhoods have frequently been defined using geopolitical boundaries (e.g., census tracts) which do not necessarily reflect the social patterns and networks influencing individuals’ behaviors. Neighborhood effects have largely relied on large survey datasets which are powerful due to their ability to identify generalizable neighborhood features that may influence health outcomes within and across populations. However, most surveys have employed cross-sectional study designs making it difficult to interpret the causal nature of observed relationships. Survey data may insufficiently capture the influence of complex cognitive, interpersonal or social processes occurring within communities that are not easily geographically bounded (R. L. Jarrett, 2000; Newman, 1996). Qualitative studies can add to our understanding by providing insights regarding the mechanisms underlying observed statistical associations. We do not propose that either approach is better, but rather that each has unique strengths.

Few studies in the US have qualitatively or quantitatively researched how the range of recreational opportunities available in communities or engagement in different types of community activities relate to adolescents’ sexual behaviors. None have explored these associations among African American adolescents who initiate sexual intercourse earlier than adolescents from other racial groups (Eaton, et al., 2006; Upchurch, Mason, Kusunoki, & Kriechbaum, 2004), are more likely to experience a pregnancy (Martyn & Martin, 2003; The Guttmacher Institute, 2006; Ventura, Mathews, & Hamilton, 2001) or an STI (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007), and are more likely to live in communities characterized by high poverty rates and fewer community resources. Finally, few studies have examined the effect of neighborhood characteristics on sexual behaviors among adolescents or adults in rural communities, particularly in southern parts of the U.S. (Adimora, et al., 2001). Neighborhood contextual factors may be important determinants of adolescent sexual behavior in rural communities where community resources, transportation, economic opportunities, and social outlets may be limited and where adolescent sexual debut may occur earlier (Crosby, Yarber, & Ding, 2000; Milhausen, et al., 2003).

Study Objective

We report data collected from focus groups conducted as part of a community needs and asset assessment from an academic-community partnership formed to reduce disparities in HIV rates among African Americans in two rural counties in northeastern North Carolina. In this analysis, we delineate mechanisms through which, according to our research participants, neighborhood features serve to encourage or protect adolescents from early sexual involvement.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted 11 focus groups in the summer of 2006 with African Americans (n=94) from two contiguous rural counties in North Carolina. We used focus groups as our primary method of data collection because, in contrast to individual interviews, focus groups allow one to gather data from a number of participants simultaneously while encouraging continual assessment of group norms, values and attitudes (Giacomini & Cook, 2000; Patton, 1998; Schatzman & Strauss, 1973). The interactive nature of the investigative process leads to greater insights regarding the origins of certain beliefs and opinions and highlights shared and variations in world-views, values and beliefs of participants.

Neighborhood setting

There is extensive literature on the definition of ‘neighborhood’ and the role of ‘place’ in relation to health. Similar to Kone and colleagues (Kone, et al., 2000), we defined ‘neighborhood’ for the purposes of this study as a group of people with pre-existing social relationships and interaction patterns who share common interests, have similar cultural backgrounds and live in the same geographic area. Our neighborhood population was comprised of African American residents of two rural counties in northeastern North Carolina. Although separated by geopolitical county lines, African Americans function as one community due to a shared social and economic history. Most reside in a racially segregated area that spans the two counties with a railroad track serving as a county line that bisects the area.

County A has 94,000 residents (37% African American) and County B has 53 thousand (57% African American) (U.S. Census Bureau, 2008). Both counties have higher rates of poverty compared to the state average with higher rates among African American residents (U.S. Census Bureau, 2008). County A has a smaller number of African Americans but is economically more advantaged. African Americans in both counties experience higher rates of HIV, STIs and teen pregnancy compared to other racial groups (Edgecombe County Health Department, 2007; Nash County Health Department, 2007)

Participants and Recruitment

We recruited a purposeful sample of three population subgroups: young people aged 16–24 years (4 focus groups, n=38), adults aged 25 years and above (5 focus groups, n=42) and formerly incarcerated individuals (2 focus groups, n=13). The perspectives of individuals from these three groups had been identified as critical to understanding local HIV rates by our community partners. All groups were stratified by gender. We conducted two focus groups each with young people of each gender; two groups with adult females and three with adult males. The additional group was conducted with adult males because so few (n=3) showed for the initial session. One focus group each was conducted with formerly incarcerated males and females. The total number of focus groups was chosen in two ways. Prior to starting the study, we estimated that we would need to perform 3–5 focus groups with each participant type to reach thematic saturation regarding the factors influencing local HIV risk. We stratified by gender to prevent discussions from being truncated if gender-sensitive topics arose, not to achieve thematic saturation for each gender-participant type combination. Once the study was underway, we noted that thematic saturation occurred for each participant type after the second focus group. Focus groups with formerly incarcerated individuals were conducted at the end of the data collection process. Because this population is small and because the data obtained were consistent with that found with the other participant types, we conducted fewer groups with this population.

Participants were recruited through local community-based organizations, public health departments, community events, media advertising and word-of-mouth. Individuals over age 18 provided verbal informed consent; minors provided verbal assent and written informed parental consent. Participants received a cash incentive of $20 and were provided with a meal at the conclusion of each focus group session. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina.

Data Collection Methods

Focus group interviews were held at local community organizations and led by two African American moderators both matched to the gender of participants. One facilitated the discussion; the other took notes. Discussions lasted approximately 2 hours. At the beginning of each focus group, participants completed a brief demographic questionnaire. The discussion guide contained 12 open-ended questions that explored participants’ perceptions of factors affecting HIV risk within the African American community; community needs, assets and resources for addressing the HIV epidemic; and solicited ideas about the types of interventions needed. Questions regarding factors affecting community HIV risk were initially broad (e.g., “Why do you think rates are higher among African Americans than Whites in this community?”) and were followed by structured probes to ensure that all focus groups addressed individual, interpersonal, social, cultural, institutional and neighborhood-level factors. Probes related to the current analysis inquired about aspects of the physical, recreational or structural environment contributing to HIV risk.

ANALYSIS

We used STATA 9.0 (StataCorp, 2005) to perform descriptive analysis of demographic data. All focus groups were audio-taped, transcribed and entered into Atlas.Ti (Scientific Software Development, 2007), a qualitative data management program. We used a well-developed theoretical model to guide our questions regarding perceived factors affecting HIV risk. However, we did not specifically set out to inquire about neighborhood factors affecting adolescent sexual behaviors. This topic emerged as important during the data collection process. We used the methodological approach to content analysis described by Strauss and Corbin (Strauss & Corbin, 1998) and the constant comparison method to identify emergent themes within and across focus groups regarding neighborhood factors and adolescent sexual behaviors. There were six independent coders. Two coded the transcripts for each participant type (young people, adults and formerly incarcerated individuals). Each pair of coders met to review their coded passages and agree on the major themes. This process, referred to as investigator corroboration, is designed to ensure data validity, consistency and guards against bias (Giacomini & Cook, 2000; Patton, 1998).

The coding process involved three steps. First, the written text was reviewed line-by-line to identify relevant themes. This open coding process resulted in a list of words and phrases representing a broad array of perceived neighborhood factors affecting adolescent sexual behaviors. Coders then met as a team to perform axial coding, where coders collectively reviewed the initial list of themes and created a codebook that organized the themes into hierarchical categories. Definitions were delineated for each major and minor theme to assist in the final coding step. In the final step, two coders independently recoded each focus group transcript using the codebook. The coders then met to review the coded transcripts and resolve discrepancies in the final coding process via consensus. We used data matrices to compare themes across individual focus groups, genders and participant types. This process of using and comparing different informants’ points of view is referred to as participant triangulation (Moran-Ellis, et al., 206). It allows us to ‘hear’ multiple sides of the ‘story’ thereby providing insights that move beyond that of each individual population group included. Reported themes arose consistently across all groups and participant types, unless otherwise noted.

RESULTS

SAMPLE CHARACTERISTICS

Table 1 shows the sample characteristics. Half of young people and adult participants but only a third of formerly incarcerated individuals were female. More than a third of adults and two-thirds of formerly incarcerated individuals had less than a high school education. Few adult participants earned more than $40,000 annually.

Table 1.

| Characteristic | General Adult (N=42) | Formerly Incarcerated Adults (N=13) | Adolescent & Young Adult (N=38) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender | 24 (57) | 4 (31) | 18 (47) |

| Mean age | 34.4 ± 7.5 | 37 ± 7.9 | 18.1 ± 2.0 |

| Education | |||

| ≤ High school | 16 (38) | 9 (69) | 5 (79) |

| Post-secondary education | 24 (57) | 2 (15) | 2 (14) |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married or living with a partner | 13 (31) | 3 (23) | 0 |

| Separated, widowed or divorced | 10 (24) | 2 (15) | 1 (7) |

| Never married | 18 (43) | 8 (62) | 13 (93) |

| Annual Income | |||

| <20,000 | 14 (33) | 10 (77) | 18 (47) |

| 20,000 to ≤ 40,000 | 21 (50) | 2 (15) | 10 (26) |

| ≥ 40,000 to ≤ 60,000 | 5 (12) | 0 | 4 (10) |

All data are shown as number *(n) followed by percent (%), unless otherwise specified.

Percents do not sum to 100% where there is missing data.

THEMATIC OVERVIEW

Participants identified six neighborhood characteristics they believed affected adolescent sexual behaviors: (1) an absence of a structured built environment for recreation, (2) lack of diverse leisure-time activities targeting older adolescents, (3) lack of recreational options for adolescent dating, (4) adolescent access to inappropriate leisure time activities that promote multiple risk behaviors, (5) limited safe environments for socializing, and (6) cost-barriers to alternative recreational activities for adolescents. This quote by a male young person epitomizes several of these themes:

“These things get in the way [of reducing HIV and sexual behaviors among young people]: the YMCA ain’t free. the community is divided by gangs; [there’s] no place to hold concerts; [there’s] nothing downtown; [the] youth [are] losing parks to gang activity…”.

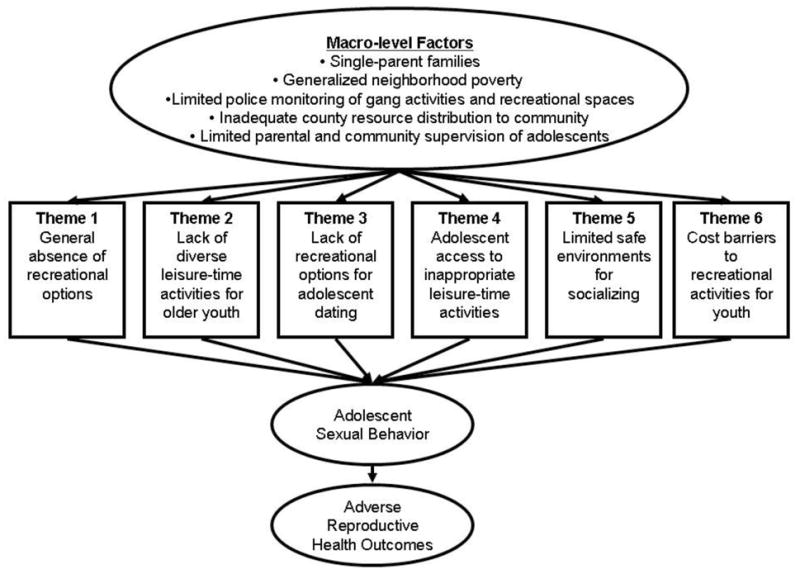

These six themes broadly connote a community in which sexual activity is seen as a recreational default for adolescents who have few other opportunities to engage in alternative forms of ‘recreation’ whether structured or unstructured. Our findings also indicate that community monitoring of adolescents’ activities is not only inadequate but that adolescents’ sexuality is exploited by some local entertainment establishments for financial gain, a situation adults in the community feel powerless to change. These six inter-related themes are a reflection of broader economic and institutional forces that dictate resource allocation and job opportunities within the communities studied. The relationship between these six major neighborhood factors, the broader socio-economic forces and adolescent sexual behaviors are depicted in the conceptual model we developed, based on our results and presented in Figure 1. Each of the six community characteristics is described in more detail below. Because the content of discussion of these themes was generally consistent across participant types and gender, we do not provide detailed comparisons by participant types or gender except to highlight where differences emerged.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model linking neighborhood characteristics to adolescent sexual behaviors

ABSENCE OF STRUCTURED BUILT ENVIRONMENTS FOR RECREATION

Across all focus groups, participants perceived an overall lack of neighborhood recreational opportunities within their communities, whether for adolescents or adults. Regarding activities specifically targeting adolescents, one formerly incarcerated male said:

“We have drugs. We got whore houses. You got gang activity like real estate. We don’t have no other outside activities for them [adolescents] to do, like the boy scouts.”

When asked what recreational options existed, participants most commonly responded, ‘None’. They identified a long list of indoor (e.g., bowling alleys), outdoor (e.g., miniature golf, amusement parks, drive-in movie theatres), sports-related (e.g., ice-skating rink, hockey field) and cultural (e.g., art museums, theater) resources that their community lacked and that they desired.

Adults felt more adolescent-targeted recreational options existed when they were young compared to the present. These included programs run through schools, churches, and community centers as well as those organized informally by community adults.

“When I was coming up, we had little league baseball. We had somewhere to go. They [adolescents today] ain’t got nothing to do.” (Formerly incarcerated male)

Of the few available recreational opportunities, multiple barriers to their use were described. Facilities were not well lit or well-maintained, lacked adequate security and sufficient diversity to engage adolescents of various ages. The comment below illustrates concerns about facility maintenance.

“Well, the one [community center] in my neighborhood, has a tennis court. We have a baseball field. We have a basketball court. But the grass is so tall in the courts you can’t play tennis there. I play tennis but I have to go to [another neighborhood] to play because I can’t go right around the corner. That basketball court has glass all over it.” (Female young person)

Given the limited number of facilities and lack of public transportation, community members complained the few available recreational activities were often difficult to get to, particularly for adolescents who often rely on others for transportation.

Participants wanted improvements to existing facilities’ programming. Young people and older adults complained that available programs primarily focused on sports or targeted select age-groups, such as younger children and pre-teens. This narrow focus was believed to prevent many older teens from exploring resources at the few available recreational and community centers. In order to draw more adolescents into existing programs, they recommended that programs be expanded to appeal to a wider range of interests.

“Would be [nice] having a community center which offers homework and tutoring and counselors that [adolescents] can talk to about whatever issues they may be dealing with. Or extending the hours to ten o’clock for those parents that work the second shift and don’t get home until later. Providing sport activities for them like football, basketball, volleyball, whatever they want to play. Teaching them how to develop better hygiene and better nutrition, and also career development. A community center that offers all of that shouldn’t be that hard to do that.” (Adult female)

Participants viewed the general lack of recreational opportunities for adolescents as a mediator of other risk behaviors as well, not just sexual risk behaviors.

“The kids that are in the neighborhood can’t go play in the park. Can’t swing no more. That’s why they’re hanging around bored trying to do their drug stuff.” (Formerly incarcerated male)

Adults complained that local adolescent programs experienced chronic staffing shortages resulting in few positive role models for adolescents. They particularly lamented the dearth of individuals from within the community staffing local adolescent programs and serving as role models.

“When my parents were coming along, they had role models, you know. They had the coaches and school teachers. (Adult female)”

The void was felt to be particularly pronounced for adolescent males. Role models from within the community were seen as having the power to model alternative social norms that emphasized the power of education, the possibility of success and the importance of giving back to one’s community.

Respondent: What stands in our way is positive role models, motivational speakers and adults. Adults needs to be serious in terms of drawing lines [demonstrating positive social norms].

Respondent: I mean you got a lot of adults. That doesn’t mean they does it. (Female young people)

LACK OF DIVERSE LEISURE-TIME ACTIVITIES TARGETING OLDER ADOLESCENTS

Lack of recreational opportunities was perceived to be particularly pronounced for adolescents between the ages of 14 and 21, the age group community members believed were at highest risk for engaging in sexual activities and experiencing adverse sexual outcomes, such as teen pregnancy. Adults and young people agreed there were more structured activities, such as weekend or after school programs, for young children and pre-teens than for older adolescents. Boredom resulting from lack of recreational opportunities was felt to increase adolescent engagement in sexual activities.

“If you live here your whole entire life, there’s really nothing to do. If you’re 14, 15 years old you have nothing to preoccupy your time. So, you just basically sit around and talk about sex. And, if you talk about it long enough you’re going to end up doing it. And, if you end up doing it, you don’t care who you’re doing it with. ” (Female young person)

This exchange by participating male young people was also supportive.

Moderator: We got football, basketball, school sports, a fare once a year and a parade every holiday. What other kids of activities do they [adolescents] do around here?

Respondent: That’s it.

Respondent: [It’s] like a ghost town…

Respondent: You got nothing to do but talk to a girl. That’s all you can do around here.

Respondent: The average dude from [here], when he go outside, first thing he say [is], ‘I’ m about to go look to meet some girl.’

Moderator: So girls are your recreation. That’s your playground?

Respondent: Yeah [general agreement].

The lack of recreational options was noted to be problematic not only during the school year, but also during summer months when adolescents, particularly older adolescents, are often not registered for structured activities.

“I think if you had more social activities that teenagers and preteens can go to like bowling, swimming, and camps instead of them just loafing on the street during the summer months, that would give them an opportunity to learn and see how other people get along instead of just, you know, just sitting around watching the girls.” (Adult male)

An adult female stated, “[We need] More programs for the older kids ‘cause once they leave middle school there’s not really anything for them to do after school and on the weekends.” The lack of late night recreational options for older adolescents was also cited as problematic. Both young people and adults acknowledged that ‘hanging out’ at night was relatively common for older adolescents who have few places to congregate. Meeting friends at local stores open 24 hours is common. As one male young person commented, “Everything closes at 9 o’clock…except Wal-Mart. They stay open 24 hours.” It was suggested that this lack of structured, supervised activities for adolescents at night created opportunities to engage in risky behaviors. A female young person stated, “There’s not enough positive activities for young people at night. The later you’re up, the more negative you’re gonna be thinking.”

LACK OF RECREATIONAL OPTIONS FOR DATING AND INAPPROPRIATE LEISURE TIME ACTIVITIES

The themes regarding ‘lack of recreational options for dating’ and ‘inappropriate leisure time activities’ are presented together because they are integrally linked. Although young people and adults describe their community as lacking diverse recreational opportunities, young people specifically described the absence of places to go on dates as a major contributor to adolescent sexual activity.

“Me and my boyfriend, we go out and we have fun. Like we go bowling or we’ll go to a movie and go out to eat. But if we spend the whole day together that ends about 5:00pm. It’s like, ‘What’s to do now?’ And like even if we do go home and watch probably another movie, by that time it’s like “I’m tired or watching a movie” and you just do it.” (Female young person)

A male young person corroborated this stating, “You go to the club, after that you go to a hotel room with your girl.”

Adults and young people report that because of the relative absence of public space for adolescent socializing and dating, an underground social environment has developed in which local hotels and adult night clubs provide unsupervised space for adolescents to socialize. Adults report these venues also provide adolescents access to drugs and prostitutes. Adults described night clubs admitting underage clients, including girls as young as age 14, often waiving cover charges. The rationale, they explained, was that attractive young women attract men of drinking age ensuring revenue from both cover charges and alcohol purchases. In addition, local hotels reportedly rent rooms to underage adolescents by the hour with these rentals used either for parties or young couples to have sex.

Me and my boyfriend, when we plan a date we’ll go out to eat. We’ll go to the movies. And we’re looking for other stuff to do besides just go get a room. I mean that ain’t even like what we made plans to do, just go get a room and have sex. But because there’s nothing else to do we end up either at his house or my house and, you know, that’s just what happens. But if we had other stuff to do and to occupy our time…” (Female young person)

Although adults described being aware of the problems presented by some local night clubs and hotels, they describe feeling powerless to change it. An adult male said, “They [hotel management] don’t care…They [young people] can get [a room] at a young age.”

An underlying theme throughout these discussions was lack of parental supervision of adolescent social and dating activities. This lack of supervision provides adolescents with opportunities to have sex. Adults described two main things that limit their ability to supervise adolescents’ leisure-time activities. First, many parents travel long distances for work because there are few well-paying jobs in the area. This means adolescents are often left home alone before and after school providing an opportunity for sex to occur. Second, the high prevalence of single-parent households limits parents’ ability to monitor children, particularly older adolescents. Both these issues are described in the following quote by an adult male participant:

The simple fact you got to also look at that a lot of parents work second and third shift. So their kids are out when no one’s home. And then there’s a lot of single parent homes. (Adult male)

LACK OF SAFE ENVIRONMENTS FOR SOCIALIZING

Participants complained that existing facilities – both indoor and outdoor - lack adequate adult supervision or police monitoring. One adult female said, “If we could do one thing for instance, a safer environment…You want to be able to go outside with your kids and play…You don’t want to go out there and be shocked by the things that are in the community.” Police were perceived as reluctant to monitor the community unless major criminal events necessitated their involvement. Young people complained that police limit their recreational mobility. When they gather socially in public spaces, police reportedly routinely request they disperse. This occurs at the local mall, in stores, on the street, and even in the park during the summer. A male young person said, “You can be at Wal-Mart…it can be like five of us. They’ll [security or police] walk right behind us…” Another male young person said, “You can’t stand outside in the summer time without being bothered, man”

Thus, young people feel restricted to socializing within their homes or within their immediate neighborhoods, situations that either lead to sexual opportunity or are often unchaperoned social situations.

Community-level violence affects adolescent recreational options and social movement in ways that were linked to sexual behavior. Gang violence, drug sales and drug use at recreational sites were reportedly common and serve to limit utilization of recreational sites by young children and adolescents.

“The baseball field - I mean that’s like way back there in the woods. And then it’s always a lot of drug dealers in our neighborhood so it’s always like older guys there. Always a bunch of guys just standing around on the playground where the kids are supposed to be playing.” (Female young people)

Non-gang related violence, referred to as “haterism”, was defined as conflict between residents from different neighborhoods with long-standing social conflict that erupt unpredictably when people gather together in groups. These conflicts were thought to limit social activities because they often lead to violence when community members congregate such as for sporting events, family cook-outs, or community celebrations in the parks.

COST-BARRIERS TO ALTERNATIVE RECREATIONAL ACTIVITIES FOR ADOLESCENTS

Although participants believed there was an overwhelming dearth of recreational options in their community, they felt the price associated with existing options were prohibitive, especially given the high local poverty and unemployment rates. A formerly incarcerated female said, “Some of these places you go to…you’ve got to have membership or you’ve got to pay. That child ain’t always got no money to go pay to go to no gym.”. A formerly incarcerated male linked the lack of recreational options, cost and adolescent sexual behaviors: “They [adolescents] ain’t got nothing to do. Trying to look pretty and everything like that… We ain’t got no money. We ain’t got nothing else to do but mack-daddy and trick [‘pimping’ and prostitution].” Most available recreational resources are located in the county with the fewest number of African Americans. Resources are restricted to county residents but can be accessed by those outside the community at a much higher cost than that charged to county residents.

“In [X County], you have to live within the city limits. But if you don’t live within the city limits, you have to pay a fee to participate.” (Formerly incarcerated male)

Coupled with limited that public transportation in the region, the cost barrier makes recreational access even more challenging, particularly for adolescents. Creative solutions to circumvent some of the economic barriers were offered including more free activities or have tiered payment systems based on income.

DISCUSSION

As detailed in the introduction, studies that provide local contextual descriptions explicating which neighborhood features serve as an impetus for adolescent sexual behaviors are limited. Data from rural communities are non-existent. We found that structural factors, such as neighborhood poverty and economic disenfranchisement, operate synergistically with features of the community’s social organization to foster situations of sexual opportunity for adolescents.

Previous authors writing in the US have proposed frameworks for understanding how communities influence adolescent sexual behavior (Brooks-Gunn, & Billy et al). These frameworks hypothesize that sex is a rational choice for adolescents who lack opportunities to accrue social or financial capital. Neither adolescents nor adults in our sample endorsed these beliefs. Rather, the cost and limited availability of recreational options along with deficits in community monitoring reportedly create sexual opportunities.

Previous studies have examined the relationship between situations of sexual possibility and adolescent sexual behaviors. Situations of sexual possibility include time spent at home without an adult present (Cohen, et al., 2002), residing in neighborhoods with large concentrations of idle adolescents (Cubbin, et al., 2005) and time spent in mixed-sex groups without adult supervision (Paikoff, 1995). However, the aforementioned studies did not, in fact, examine children and adolescents in the context of dating relationships. This is where our study makes a significant contribution to the existing literature. Our respondents saw a clear association between the lack of neighborhood recreational options for adolescents while on dates and adolescent sexual behaviors. Neighborhood recreational activities occupy adolescents’ free time thereby reducing the amount of time available for adolescents to have sex. Participation in neighborhood activities appear to reduce adolescent sexual behaviors by alleviating boredom, providing adult supervision, and exposing adolescents to alternative peer and adult role models whose social norms do not favor engagement in sexual behaviors.

As noted in the introduction, community monitoring of adolescents reduces adolescent engagement in risk-taking behaviors, including sexual behaviors. However, measures of collective community monitoring generally assess community members’ beliefs that neighbors provide non-specific support to one another (e.g., “People around here are willing to help their neighbors”). Such measures are useful, but fail to capture specific ways in which community members’ actions may affect adolescent sexual behaviors. We identified two concrete ways in which community members’ lack of monitoring of adolescent behaviorscan result in increased opportunities for sexual activity among adolescents; through adolescents’ access to adult night clubs and access to hotel parties. These specific, local contextual situations have not been previously reported in the literature.

From our data, two separate but linked concepts also emerged as important contextual features of neighborhoods. Access to activities for young people clearly depends on community resources to provide services and amenities, and also on their individual ability to pay. In this paper, participants indicated that poverty and the absence of community resources provided by social institutions (e.g., churches), city and county governing bodies influenced adolescent sexual behaviors. Research on child and adolescent development has tended to focus on the effects of poverty rather than emphasizing the benefits that access to socioeconomic and institutional resources may have on child health and development. Our finding suggest that improving a community’s ‘wealth” of institutional resources represents a key protective factor for adolescents and may be a more feasible, short-term intervention target than addressing the more socio-politically complex issues that create and sustain neighborhood poverty.

Limitations

This study was conducted in one community thus our findings may not apply to populations from other geographic locations or with other socio-demographic characteristics. Due to selection bias among those who chose to participate, our findings may not fully reflect the opinions of all community members. The parent study was not designed to solely examine the relationship between the community-level recreational options and adolescent sexual behaviors. Future work should explore exactly what recreational opportunities are available in communities and examine the relationship between the utilization of these resources by adolescents and association with dating and sexual behaviors.

We did not objectively identify the range of recreational opportunities are actually available within these communities; thus, we cannot confirm participants’ belief that these communities largely lack adolescent-targeted recreational options. However, this perception was consistent across all focus group types and genders suggesting the validity of these findings. It is unlikely that the relationship between a neighborhood’s recreational opportunities and adolescent sexual behaviors is as simple as lacking the former results in the latter. It is equally, if not more likely, that neighborhoods that lack recreational options for adolescents are also lacking other important social and infrastructural services that also contribute to adolescent sexual risk behaviors. This last assumption is most consistent with previously cited studies linking neighborhood characteristics to child health and is more consistent with the broader picture our participants painted of their own community.

CONCLUSIONS

Neighborhoods affect adolescent sexual behaviors in complex ways. Macro-level features such as community-level poverty, job availability and local institutional resources have down stream effects on the ability of adults to supervise and act as role models for adolescents. These features affect adolescents’ recreational opportunities and perceived social norms regarding sexual activity. Interventions that seek to address all of these factors simultaneously are unlikely to be financially feasible, could stretch thin available human resources and be challenged to identify concrete measures of local change that map directly to adolescent sexual behaviors. On the other hand, interventions that focus on singular issues without changing some of these larger structural constraints on free-choice may ultimately appear ineffective even if they do have some targeted, positive impact. This is where the in-depth, qualitative neighborhood-level focus of our approach is most helpful. It allowed us to identify critical local issues that can be operationalized as measurable intervention targets (e.g., restricting adolescent access to local clubs and hotels). Future studies may want to qualitatively identify available and desired recreational opportunities then quantitatively explore the relationship between available recreational opportunities and rates of teen pregnancy, HIV infection and other sexual health behaviors and outcomes perhaps using innovative approaches such as geographic information systems (GIS).

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Selena Youmans (Project Coordinator); Connie Blumenthal (Project Manager) Bahby Banks and Stacy Lloyd who assisted with coding the transcripts and our numerous community partners.

Sources of funding: Sources of support: This project was funded by grants from the National Center on Minority Health Disparities (R24MD001671) and the UNC Center for AIDS Research (UNC CFAR P30 AI50410). Dr. Akers was funded by NIH Roadmap Multidisciplinary Clinical Research Career Development Award Grant (1 KL2 RR024154-01) from the National Institutes of Health. The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH. Information on NCRR is available at http://www.ncrr.nih.gov/. Information on Re-engineering the Clinical Research Enterprise can be obtained from http://nihroadmap.nih.gov/clinicalresearch/overview-translational.asp.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Aletha Y. Akers, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA UNITED STATES, aakers@mail.magee.edu

Melvin R Muhammad, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Giselle Corbie-Smith, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson FE, Donaldson KH, Fullilove RE, Aral SO. Social context of sexual relationships among rural African Americans. Sex Transm Dis. 2001;28(2):69–76. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200102000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronowitz T, Rennells RE, Todd E. Ecological influences of sexuality on early adolescent African American females. J Community Health Nurs. 2006;23(2):113–122. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn2302_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averett SL, Rees DI, Argys LM. The impact of government policies and neighborhood characteristics on teenage sexual activity and contraceptive use. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(11):1773–1778. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.11.1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billy JO, Brewster KL, Grady WR. Contextual Effects on the Sexual-Behavior of Adolescent Women. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1994;56(2):387–404. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ, Klebanov PK, Sealand N. Do neighborhoods influence child and adolescent develoment? American Journal of Sociology. 1993;99(2):353–395. [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Neighborhood context and racial differences in early adolescent sexual activity. Demography. 2004;41(4):697–720. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC Cfdcap. Special focus profiles: STDs in adolescents and young adults. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in Reportable Sexually Transmitted Diseases in the United States, 2006: National Surveillance Data for Chlamydia, Gonorrhea, and Syphilis. Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D, Farley T, Taylor S, Martin D, Schuster M. When and where do youths have sex? The potential role of adult supervision. Pediatrics. 2002;110(6):e66. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.6.e66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane J. The epidemic theory of ghettos and neighborhood effects on dropping our and teeage childbearing. Am J Sociology. 1991;96:1126–1159. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby R, Yarber W, Ding K. Rural and nonrural adolescents HIV/STD sexual risk, behavior; a comparison from a national sample. Helath Education Monograph Series. 2000;18:45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cubbin C, Santelli J, Brindis CD, Braveman P. Neighborhood context and sexual behaviors among adolescents: findings from the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2005;37(3):125–134. doi: 10.1363/psrh.37.125.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinche S, Ross J, Hawkins J, Harris WA, et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2005. Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. 2006;55(SS-5):1–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgecombe County Health Department. Report from the Edgecombe County Health Department. Edgecombe County Health Department; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH, Eccles JS, Ardelt M, Lord S. Inner-city parents under economic pressure: Perspectives on the strategies of parenting. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:771–784. [Google Scholar]

- Giacomini MK, Cook DJ. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research in health care B. What are the results and how do they help me care for my patients? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. Jama. 2000;284(4):478–482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.4.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttmacher Institute. Facts on American Teens’ Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2006 Retrieved November 16, 2006, from http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/fb_ATSRH.html.

- Hogan D, Kitagawa E. The impact of social status, family structure an dneighborhood on the fertility of black adolescents. Am J Sociology. 1985;90:825–855. [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett R. Neighorhood Poverty: Vol 2 Policy implications in studying neighborhoods. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1997. Bringing families back in: neighborhoods’ effects on child development; pp. 48–64. [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett RL. Bringing Families Back in: Neighborhood effects on child development. In: Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ, Aber JL, editors. Neighborhood Poverty, Vol 2: Policy implications in studying neighborhoods. New York: Russel Sage Publications; 2000. pp. 48–64. [Google Scholar]

- Jencks C, Mayer S. Inner City Poverty in the United States. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 1990. The social consequences of growing up in a poor neighborhood; pp. 111–186. [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Berkman L. Social cohesion, social capital, and health. In: Barkman L, Kawachi I, editors. Social Epidemiology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 174–190. [Google Scholar]

- Kone A, Sullivan M, Senturia KD, Chrisman NJ, Ciske SJ, Krieger JW. Improving collaboration between researchers and communities. Public Health Rep. 2000;115(2–3):243–248. doi: 10.1093/phr/115.2.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korbin JE, Coulton CJ. Understanding the neighborhood context for children and families: Combining epidemiological and ethnographic approaches. In: Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ, Aber JL, editors. Neighborhood Poverty, Vol 2: Policy implications in studying neighborhoods. New York: Russel Sage Foundation; 2000. pp. 65–79. [Google Scholar]

- Ku L, Sonnenstein F, Peck J. Neighborhood, family, and work: Influences on the premarital behaviors of adolescent males. Social Forces. 1993;72:479. [Google Scholar]

- Martyn KK, Martin R. Adolescent sexual risk assessment. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health. 2003;48(3):213–219. doi: 10.1016/s1526-9523(03)00064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milhausen RR, Crosby R, Yarber WL, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Ding K. Rural and nonrural African American high school students and STD/HIV sexual-risk behaviors. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2003;27(4):373–379. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.4.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Sabo DF, Farrell MP, Barnes GM, Melnick MJ. Athletic participation and sexual behavior in adolescents: the different worlds of boys and girls. J Health Soc Behav. 1998;39(2):108–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KE, Sabo DF, Farrell MP, Barnes GM, Melnick MJ. Sports, sexual behavior, contraceptive use, and pregnancy among female and male high school students: testing cultural resource theory. Sociol Sport J. 1999;16(4):366–387. doi: 10.1123/ssj.16.4.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran-Ellis J, Alexander VD, Cronin A, Fielding M, Sleney J, Thomas H. Triangulation and integration: Process, claims and implications. Qualitative Research. 2006;6(1):612–621. [Google Scholar]

- Nash County Health Department. Report from the Nash County Health Department. Nash County Health Department; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Newman O. Creating defensible space. Center for Urban Policy Research, Rutgers University; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Oman R, Vesely S, Aspy C. Youth assest and sexual risk behavior: the importance of assets for youth residing in one-parent households. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2005;37(1):25–31. doi: 10.1363/psrh.37.25.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paikoff R. Early heterosexual debut: situations of sexual possibility during the transition to adolescence. AM J Orthopsychiatry. 1995;65(3):389–401. doi: 10.1037/h0079652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Services Research. 1998;34:1189–1208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatzman L, Strauss AL. Field Research: Strategies for a natural sociology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Scientific Software Development. Atlas.Ti. 5.2. Berlin, Germany: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Statistical Software: Release 9.0 (Version 9.0) College Station, TX: Stata Corporation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tesoriero JM, Parisi DM, Sampson S, Foster J, Klein S, Ellemberg C. Faith communities and HIV/AIDS prevention in New York State: results of a statewide survey. Public Health Rep. 2000;115(6):544–556. doi: 10.1093/phr/115.6.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Guttmacher Institute. US Teenage Pregnancy Statistics National and State Trends and Trends by Race and Ethnicity. New York: The Guttmacher Institute; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. US Census Bureau: State and County QuickFacts. 2008 Retrieved September 12, 2009, from U.S. Census Bureau: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/37/37127.html.

- Upchurch DM, Mason WM, Kusunoki Y, Kriechbaum MJ. Social and behavioral determinants of self-reported STD among adolescents. Perspectives on Sexual & Reproductive Health. 2004;36(6):276–287. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.276.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura SJ, Mathews TJ, Hamilton BE. Births to teenagers in the United States, 1940–2000. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2001;49(10):1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W., Jr Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36(1):6–10. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.6.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zill N, Nord C, Loomis L. Adolescent time use, risky behavior and outcomes: an analysis of national data. Rockville, MD: 1995. [Google Scholar]