Abstract

Humans have populated the Tibetan plateau much longer than the Andean Altiplano. It is thought that the difference in length of occupation of these altitudes has led to different responses to the stress of hypoxia. As such, Andean populations have higher hematocrit levels than Himalayans. In contrast, Himalayans have increased circulation to certain organ systems to meet tissue oxygen demand. In this study, we hypothesize that cerebral blood flow (CBF) is higher in Himalayans than in Andeans. Using a MEDLINE and EMBASE search, we included 10 studies that investigated CBF in Andeans and Himalayans between 3,658 and 4,330 m altitude. The CBF values were corrected for differences in hematocrit and arterial oxygen saturation. The data of these studies show a mean hematocrit of 50% in Himalayans and 54.1% in Andeans. Arterial oxygen saturation was 86.9% in Andeans and 88.4% in Himalayans. The CBF in Himalayans was slightly elevated compared with sea-level subjects, and was 24% higher compared with Andeans. After correction for hematorit and arterial oxygen saturation, CBF was ∼20% higher in Himalayans compared with Andeans. Altered brain metabolism in Andeans, and/or increased nitric oxide availability in Himalayans may have a role to explain this difference in brain blood flow.

Keywords: adaptation, Andean, cerebral blood flow, high altitude, Himalayan

Introduction

For thousands of years, populations have inhabited the high-altitude plateaus in the Andes in South America and the Himalayas in Tibet, where they have responded to the stress of the high-altitude hypoxia. The first humans arrived in South America and lived on the highlands of Bolivia and Peru for more or less 12,000 years. Since the Spanish Conquest, which started in the early 1,500s, considerable genetic admixture has occurred with the indigenous Andean populations, resulting in the introduction of 5% to 30% of European genes into the contemporary Andean gene pool. In contrast, the Tibetan plateau was populated much earlier. Human handprints and footprints, discovered at 4,200 m, have demonstrated the existence of modern man already 20,000 years ago (Zhang and Li, 2002). It is thus probable that the Himalayan model of adaptation is different from the Andean model as the latter had a shorter time interval for adaptation and displays probably more genetic admixture from lowland populations, which were not adapted to the high-altitude hypoxia. This difference implies that the evolutionary adaptation of the Andeans and Himalayans followed divergent pathways (Moore, 2000).

As an example of the difference in response to the high-altitude hypoxia Andeans have, at altitudes of ∼4,000 m, hemoglobin levels, which are consistently higher compared with Himalayans, whereas hemoglobin levels in Himalayans are only slightly higher than in subjects at sea level (Beall et al, 1998). In contrast to this substantial difference in hemoglobin levels, the oxygen saturation, which is normally decreased at altitude because of a decrease in ambient oxygen pressure, is found to be more or less similar in the two populations (Moore, 2000). As a result, the arterial oxygen content, being a measure of the oxygen carrying capacity, which is determined by hemoglobin concentration and oxygen saturation, has been found to be higher in Andeans than in Himalayans (Beall, 2007). This implies that Himalayans must engage other mechanisms to sustain normal oxygen delivery and aerobic metabolism (Beall, 2007). In fact, it has been shown that Himalayans have increased blood flow to several body tissues to sustain an adequate tissue oxygen delivery: Tibetans have higher forearm blood flow as compared with sea-level subjects (Erzurum et al, 2007), and Tibetan pregnant women have a higher placental blood flow than Han Chinese at 3,860 m (Moore et al, 2001).

On the basis of these observations, it is a logical and intriguing idea to test the hypothesis whether Himalayans have higher cerebral blood flow (CBF), as compared with Andeans, to meet oxygen demand of the brain at high altitude. To this end, we undertook a study of the literature to investigate whether we could find the evidence which supports this hypothesis.

Materials and methods

In the preparation of this manuscript, the term ‘Andean' was used to represent Aymara and Quechua Indians who live on the high-altitude plains of Bolivia and Peru. The term ‘Himalayan' was used to represent Tibetans and Sherpas. Sherpas live in the Northern highlands of Nepal and are of Tibetan ancestry.

A MEDLINE and EMBASE literature search using the terms (MESH): (Andeans, Himalayans) OR (Aymara, Quechua, Tibetan, Sherpa) AND (altitude) OR (brain) OR (cerebral blood flow) was performed to include articles published between the years 1960 and 2008. In all, 12 articles were found that describe CBF measurements performed at altitudes between 3,658 and 4,330 m. Two of these were not included, as data were missing or not adequately powered (Wood et al, 1988; Sun et al, 1996). In total, 10 articles published in peer-reviewed journals were used for comparison to be drawn regarding the CBF and CBF-related values in the two high-altitude populations. The methodological heterogeneity of the CBF measurements precluded any formal statistical analysis, and data were analyzed descriptively. The CBF and CBF-related values from the high-altitude populations were compared with their sea-level control group values. When such control groups were lacking, standard sea-level values were used.

Results

The Andean Altiplano

Milledge and Sørensen (1972) measured the arterial-venous oxygen content difference of the brain ((A-V)DO2) of high-altitude residents of Cerro de Pasco at 4,300 m (Table 1). (A-V)DO2 is an approximation of CBF, and is expressed as mL oxygen bound in 100 mL blood, expressed as volume percent (vol%). Proportional as CBF diminishes, more oxygen is extracted from the blood flowing through the brain, resulting in an increase in (A-V)DO2, and vice versa. Thus, a reverse linear relationship exists between CBF and (A-V)DO2. Standard sea-level (A-V)DO2 values in healthy adults are ∼6.5 vol%. The authors of that study measured (A-V)DO2 value of 7.89 vol% in the high-altitude residents and of 6.5 vol% in a control group at sea level. After comparing these (A-V)DO2 values with other (A-V)DO2 and CBF data that were measured during a similar high-altitude study (Sørensen et al, 1974), a mean CBF value of 38 mL per 100 g per minute in the high-altitude residents was calculated.

Table 1. Physiological characteristics of Himalayan and Andean high-altitude residents.

| Alt | n | Vmca | Vica | CBF | (A-V)DO2 | hct | SaO2 | PetCO2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Himalayans | |||||||||

| Huang et al (1992) | 3,658 | 15 | — | 22.9±0.9 | — | — | 50a | 89.9±1 | 31.2±0.5 |

| Jansen et al (1999) | 4,243 | 20 | 59±13 | — | — | — | — | 86±4 | 32±4 |

| Jansen et al (2000) | 4,243 | 10 | 61±11 | — | — | — | — | 89±2 | 31±5 |

| Jansen et al (2007) | 4,243 | 10 | 59±10 | — | — | — | 49±5 | 88±3 | 31±2.3 |

| Mean (n) | (55) | 60 | 50 | 88.4 | 31 | ||||

| Andeans | |||||||||

| Milledge and Sørensen (1972) | 4,300 | 8 | — | — | 38b | 7.89±1.0 | 57.8±6.3 | 81c | 34±2 |

| Marc-Vergnes et al (1974) | 3,750 | 16 | — | — | 40.2±1.4 | 8.48±0.4 | — | 91c | 28.9±0.5 |

| Sørensen et al (1974) | 3,800 | 13 | — | — | 45d | 7.08 | 50 | 88c | 33.5±0.7 |

| Appenzeller et al (2004) | 4,330 | 12 | 51.8±4 | — | — | — | 53.7±1.4 | 87.6±1 | 33.6±0.6 |

| Claydon et al (2005) | 4,330 | 11 | 50±4 | — | — | — | 53.6±1.2 | 86±1 | 27.3±1.2 |

| Appenzeller et al (2006) | 4,330 | 9 | 45.8±8 | — | — | — | 57.9±11 | 83.8±6 | 31.8±3.5 |

| Mean (n) | (69) | 49.4 | 41.4 | 7.86 | 54.1 | 86.9 | 31.5 | ||

alt, altitude (m); (A-V)DO2, arterial–jugular venous oxygen difference (vol%); CBF, cerebral blood flow (mL per 100 g per minute); hct, hematocrit (%); n, sample size; PetCO2, end-tidal PCO2 (mm Hg); Vica, blood flow velocity in the internal carotid artery (cm/s); Vmca, blood flow velocity in the middle cerebral artery (cm/s); SaO2, arterial oxygen saturation (%).

Calculated from hemoglobin value (after Sun et al, 1996).

Calculated from (A-V)DO2 values (after Sørensen et al, 1974).

Calculated from standard arterial PO2 values.

Extrapolated from (A-V)DO2 values.

Sørensen et al (1974) measured (A-V)DO2 and CBF, using the Kety–Schmidt method, in high-altitude residents in La Paz in Bolivia at 3,800 m. While breathing a hypoxic mixture at altitude, CBF was 57 mL per 100 g per minute and (A-V)DO2 was 5.62 vol%. During oxygen breathing, CBF was 36 mL per 100 g per min and (A-V)DO2 was 8.15 vol%. During ambient air breathing, an (A-V)DO2 value of 7.08 vol% was measured, but CBF was not recorded. If we extrapolate these data, and assuming no change in brain oxygen metabolism, a CBF value of 45 mL per 100 g per min in ambient air was calculated.

This basic finding of low-CBF values in Andeans was confirmed by Marc-Vergnes et al (1974) who measured CBF in La Paz at 3,750 m, using the Kety–Schmidt method. The CBF was 40.2 mL per 100 g per minute, and a CBF value of 50.1 mL per 100 g per minute was measured in a sea-level control group.

Transcranial Doppler measurements were performed in high-altitude residents in Cerro de Pasco at 4,330 m in three separate studies. Transcranial Doppler sonography determines the blood flow velocity of the middle cerebral artery (Vmca). The mca perfuses ∼80% of the hemisphere, and the velocity of the blood flow is considered an index of CBF, but assumes a given vessel diameter. Although a single value of Vmca cannot be compared with a single value of CBF, a group means of Vmca values is representative for a group means of CBF. Mean Vmca values as measured in Cerro de Pasco in the three studies were 45.8 cm/s (Appenzeller et al, 2004), 50 cm/s (Claydon et al, 2005), and 51.8 cm/s (Appenzeller et al, 2006). Sea-level control measurements were not performed in these three studies. Standard sea-level values are 60 cm/s.

These data yield an overall mean CBF value of 41.4 mL per 100 g per minute and a mean Vmca of 49.4 cm/s in Andean high-altitude residents. These values are, respectively, 17.2% and 18.4% (mean 18%) lower as compared with their sea-level control group values or with standard sea-level group values.

The Tibetan Plateau

Huang et al (1992) measured the blood flow velocity in the internal carotid artery in Tibetans in Lhasa at 3,658 m, being a value of 22.9 cm/s (Table 1). A historical control group at sea level had a value of 19.6 cm/s (Huang et al, 1987).

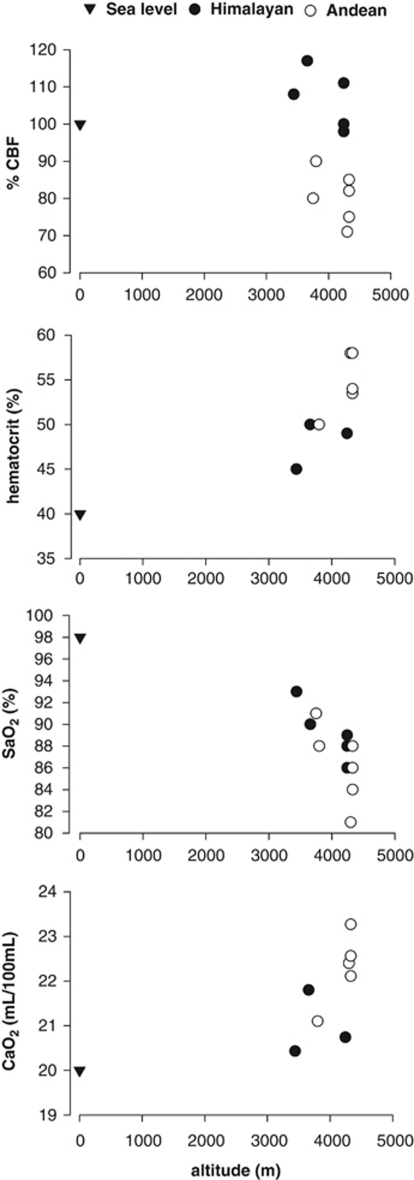

In three separate studies in Pheriche in Nepal at 4,243 m, Transcranial Doppler was used to measure Vmca in Sherpas. Vmca values were, respectively, 59 cm/s (Jansen et al, 1999), 61 cm/s (Jansen et al, 2000), and 59 cm/s (Jansen et al, 2007), with a mean value of 60 cm/s (Figure 1). Control Vmca values as measured in sea-level subjects were, respectively, 60, 55, and 58 cm/s (mean 58 cm/s). In Namche Bazar (Nepal), situated at 3,440 m, Vmca in Sherpas was 64 cm/s (Jansen et al, 2007). As the altitude of 3,440 m is beyond the range that was determined for inclusion in this study, these data are not used for further calculation. However, it is another example of the high CBF values that were encountered in the Himalayan population.

Figure 1.

Physiologic data related from 10 studies at altitudes between 3,658 and 4,330 m. Measurements of Himalayans at 3,440 m (after Jansen et al, 2007) are added for completeness. CaO2, arterial oxygen content; CBF, cerebral blood flow; SaO2, arterial oxygen saturation.

The data show that Himalayans have velocity in the internal carotid artery of 22.9 cm/s and Vmca of 60 cm/s. These values are, respectively, 11.7% and 3.4% (mean 6.2%) higher as compared with their sea-level control group values.

Discussion

The findings of this study show that Himalayans have CBF values that are slightly (6.2%) higher as compared with the sea-level control values. In contrast, Andeans living in the same high-altitude range have CBF values that are substantially (18%) lower than the sea-level control values, indicating a 24% higher CBF in Himalayan compared with Andean high-altitude populations. The difference is remarkable. However, several factors, which are known to control tightly the brain blood flow, are strongly determined themselves by high-altitude adaptation. Moreover, they are expressed differently in the two high-altitude population. These factors are hematocrit, which influences blood viscosity and rheology, arterial oxygen saturation, brain metabolism, and nitric oxide (NO) availability. They will be briefly addressed here.

Hematocrit and Altitude

The brain blood flow of high-altitude populations is actually the reflection of two opposite forces: one acting to increase flow because of the persistent low arterial oxygen tension, and the other acting to decrease flow as a consequence of the increase in hematocrit (Møller et al, 2002). Average hematocrit data, as calculated from this study, show a hct value of 54.1% in the Andean population and of 50% in the Himalayan population (Table 1). These data are in agreement with the data provided by other studies, and they underline the epidemiologic evidence for a 1 to 4 g/dL higher hemoglobin concentration in Andean compared with Himalayan populations (Beall et al, 1998; Beall, 2006). Milledge and Sørensen (1972) suggested that in the Andean population, the increased viscosity of their polycythemic blood imposed a circulatory burden, which could adequately explain their low CBF. However, Brown et al (1985), studying the relationship between blood viscosity, arterial oxygen content, and CBF, have demonstrated a highly significant correlation between arterial oxygen content and CBF. An effect of changes in blood viscosity on CBF was not evident and was less pronounced than suggested in the study of Milledge and Sørensen (1972). To eliminate any effect of differences of hct on CBF to compare normal control CBF values with CBF values in groups with varying hct values, Severinghaus (2001) proposed the following relationship:

In this equation, CBFhct-corr is the CBF after correction for the higher hct value, and CBF is the actually measured CBF. After factoring out hct in the data of this study, CBF yields a value of 46 mL per 100 g per minute in the Andean population and 56 mL per 100 g per minute in the Himalayan population.

The most striking feature after the corrections for hct is the ∼20% CBF difference between Andean and Himalayan highland populations. As the effect of the corrections for hct on CBF is small, it is thus evident that other mechanisms than the difference in hct have a role to explain the discrepancy of CBF values between the two high-altitude populations.

Arterial Oxygenation and Altitude

The data from the studies addressed here show a lower mean SaO2 (86.9%) in the Andean population compared with the Himalayan population (88.4%) (Table 1). Essentially, similar data are reported from a review that showed SaO2 of 86% in Andeans and 87.8% in Himalayans (Moore, 2000). The higher SaO2 in Himalayans at ∼4,000 m altitude is the result of a higher ventilation in Himalayans than in Andeans (Moore, 2000), and is another process of adaptation to the hypoxia of high altitude that distinguishes the Tibetans from Andeans. A decline of arterial oxygen saturation causes CBF to increase, an effect that does not adapt over time (Krasney et al, 1990), and CBF starts to increase if SaO2 falls below 88%. This would implicate that the CBF difference of ∼20% between the Andeans and Himalayans might be somewhat larger if corrected for the 1.5% SaO2 difference between the two populations.

A factor that potentially may influence the release of oxygen to the brain tissue in the two populations is their affinity of oxygen for hemoglobin, which is quantified as P50, being the arterial oxygen tension when the blood is 50% saturated with oxygen. At sea level, P50 is ∼28 mm Hg. A higher P50 means that the affinity of oxygen for hemoglobin is decreased and that the capacity of the blood to release oxygen is increased, improving tissue oxygenation. The affinity of oxygen for hemoglobin is, on the one hand, determined by the structure of the hemoglobin molecule. The structure of the hemoglobin molecule is similar in much of the animal world, and no differences are known between populations (Winslow, 2007). The affinity of oxygen for hemoglobin is, however, influenced by temperature, CO2, H+ and, within the red cell, by 2,3-diphosphoglycerate (2,3-DPG). In residents at high altitude, a small hyperventilation alkalosis is observed that produces a left shift of the oxygen dissociation curve and an increase of the affinity of oxygen for hemoglobin. This leftward shift is compensated for by an increase of 2,3-DPG that shifts the oxygen dissociation curve to the right. In effect, it was concluded that no difference was observed in the P50 of Himalayans (29.8±1.9 mm Hg) as well as of Andeans (30.1±2.2 mm Hg) compared with sea-level subjects (Winslow, 2007). It indicates that the brain oxygen delivery, and consequently CBF, in the two populations is not differently affected as a result of different binding affinity of oxygen for hemoglobin.

Beall (2007) found that arterial oxygen content, which is the product of the hemoglobin concentration and oxygen saturation, was higher in Andeans compared with sea-level subjects as a result of their high hemoglobin level, but that in Himalayans arterial oxygen content was lower and did not compensate to sea-level values. It was also supposed that the lower than sea-level arterial oxygen content in the Himalayans was the cause to increase their circulation to maintain adequate oxygen delivery (Erzurum et al, 2007). However, the arterial oxygen content values in Andeans (22.3 mL/100 mL) as well as in Himalayans (21 mL/100 mL) as calculated by us, are both above the average sea-level value of 20 mL/100 mL (Figure 1). These values are essentially similar to the values recently measured in well-acclimatized climbers on Mount Everest at an altitude of 5,300 m (Grocott et al, 2009). Thus, although brain blood flow is higher in Himalayans, the hypothesis that this high flow is a compensation for a lower than sea-level arterial oxygen content, is not justified from the data of our study. Therefore, the identical increases in arterial oxygen content in both populations do not provide an explanation for their difference in CBF.

Normally, an increase in arterial oxygen content produces a decline in CBF, such that the oxygen delivery capacity to the brain (brain blood flow × arterial oxygen content) remains constant (Brown et al, 1985; Henriksen et al, 1981). However, a low-oxygen tension in the ambient air at high altitude causes an increase in CBF, which is triggered by the decrease in arterial oxygen tension. Earlier reports showed a role for the cerebral venous oxygen tension, measured in the jugular vein (PvjO2), in the regulation of CBF (Henriksen et al, 1981; Paulson et al, 1973). The one study that determined PvjO2 in Andeans at altitude is the study of Marc-Vergnes et al (1974), which measured a PvjO2 of 29 mm Hg, with a sea-level value of 35 mm Hg. In as much as PvjO2 is a primary mover of brain circulation, the combined effect of an increase of CBF triggered by the low PvjO2 of 29 mm Hg, and a decrease in CBF that would match the 10% increase of arterial oxygen content that we measured in the Andeans (Table 1), is difficult to reconcile with the actual low CBF that we found in the Andeans. Unfortunately, PvjO2 data on Himalayans are lacking.

The influence of lifelong high-altitude hypoxia on the brain blood flow could be further evaluated by analyzing the (A-V)DO2 measurements (Table 1). These measurements, which were only performed in the Andean population, show 20% higher (A-V)DO2 values compared with sea-level values. As (A-V)DO2 is inversely related to CBF, it should be concluded that brain blood flow in the Andeans is 20% lower, on the condition that the brain oxygen metabolism (CMRO2) is not different from the sea-level value. That Andeans have similar CMRO2 as sea-level subjects, as demonstrated by Marc-Vergnes et al (1974). The alternative explanation for the increased (A-V)DO2 is that, on the condition that CBF is at the sea-level value, CMRO2 is increased in the Andean population. However, the normal CMRO2 in the Andeans precludes that this explanation is a plausible one. Therefore, we conclude that the increased (A-V)DO2 values in the Andeans contribute to our findings of a low-brain circulation in this population.

Brain Metabolism and Altitude

Sea-level dwellers who resided for several weeks at high altitude had cerebral oxidative metabolism and brain blood flow, which were not different from their sea-level values (Møller et al, 2002). Likewise, Andean high-altitude residents have cerebral oxidative metabolism, which is equivalent to that of subjects at sea level (Marc-Vergnes et al, 1974). Surprisingly, Hochachka et al (1994) found that brain glucose metabolic rate in Quechua Indians is ∼10% lower as compared with sea-level subjects, measured directly after arriving at sea level, and after 3 weeks of deacclimatization at sea level. The authors of that study described this ‘hypo-metabolism' of the brain as a defense strategy against chronic hypoxia, and compared this phenomenon with that of other vertebrate brains, which are exceptionally tolerant of extended hypoxia or even anoxia (Hochachka et al, 1996). In contrast, they also found that the brain glucose metabolic rate in Sherpas was similar to that of lowlanders and differed significantly from that of the Quechuas (Hochachka et al, 1996). These findings indicate a difference in adaptive strategy against hypoxic stress between the two populations, and they emphasize the more successful process of adaptation in the Himalayans. Although on the one hand, the finding of Hochachka and coworkers, that Quechuas have a lower brain glucose metabolism, is under discussion (Møller et al, 2002), our data, however, may support the finding of a lower brain glucose metabolic rate in the Andean high-altitude population. It should be noted that, in the human brain, blood flow and glucose metabolism are normally tightly coupled and, especially during functional brain activation, they increase in close proportion, whereas oxygen metabolism only increases to a minor degree (Madsen et al, 1995). It would mean that, in Andean high-altitude residents, the low brain blood flow is perfectly matched with the lower glucose metabolic rate.

However, the lower brain glucose metabolism does not explain what the excess oxygen delivery is used for, as brain oxygen metabolism in Andeans has been shown to be similar as in sea-level subjects (Marc-Vergnes et al, 1974). Two studies may give an explanation for this discrepancy. First, Sørensen et al (1974), who studied brain glucose and lactate metabolism in residents of La Paz (4,000 m) found in several subjects a Glucose–Oxygen Index of <100%, ‘…which might indicate that their brains metabolize something other than glucose…'. Second, in sojourners after 5 weeks at 5,260 m, a slight cerebral uptake of lactate could be demonstrated during moderate exercise (Møller et al, 2002). This may not be surprising, as it has been shown recently that, at least during exercise at sea level, the brain may consume lactate, suggesting that the human brain is not an obligatory glucose consumer (Dalsgaard, 2006). That Quechuas might possibly have an altered lactate metabolism is the notion that the lactate paradox (i.e., that blood lactate concentrations reached during maximal exercise ([La]-max) at altitude are consistently lower as compared with the values seen at sea level) in Quechuas does not disappear within 6 weeks of sojourning at sea level, whereas Tibetans born at sea level have [La]-max, similar to those of lowlanders (Kayser et al, 1996). It is thus possible that under the conditions of high-altitude hypoxic stress other substrates than glucose, hitherto overseen, are metabolized by the brain of Quechuas.

However, brain metabolism in both high-altitude populations has hardly been studied, and before we can accept these results as definitive it will be necessary to have all these measurements performed in both populations, as the implications are likely to be crucial.

Nitric Oxide and Altitude

A primary strategy to increase oxygen delivery is to increase blood flow, and numerous studies show that hypoxia produces vasodilatation. Hypoxia-induced cerebral vasodilatation in humans is mediated by NO. In healthy sea-level subjects, short-term exposure to hypoxia increases exhaled NO (Duplain et al, 2000). Beall et al (2001) have shown that exhalation of NO in Tibetans living at 4,200 m and in Aymaras at 3,900 m is increased, as compared with a low-altitude reference sample. However, Tibetans exhale twice as much NO as Aymaras (18.6 p.p.b. versus 9.5 p.p.b.), whereas exhaled NO in Aymaras was only 25% higher than in the sea-level group (7.5 p.p.b.). Relief from the high-altitude hypoxia by oxygen inspiration resulted in an increase of NO exhaled by Tibetans, but caused no change among the Aymaras (Beall et al, 2001). In a study performed in Tibetans at 4,200 m, Hoit et al (2005) showed that higher-exhaled NO was associated with higher pulmonary blood flow. Moreover, Tibetans showed, in comparison with sea-level subjects, more than double forearm blood flow and >10-fold higher circulating concentrations of bioactive NO products (Erzurum et al, 2007). Schneider et al (2001) demonstrated in Sherpas, as compared with sea-level subjects, a superior ability to increase blood flow velocity as a response to muscular ischemia. This phenomenon was probably caused by differences in conduit vessel function, and was reported to be a characteristic effect of drugs that act via NO such as nitroglycerine and nitroprusside-Na, which are both NO donors. In contrast, in Aymara children, exhaled NO tended to be lower than in European children living at the same altitude (Stuber et al, 2008). These data suggest that the metabolic pathways controlling formation of NO products, and the mechanism for sustaining high NO levels, are regulated differently among Tibetans and Andeans.

Although from these NO studies a causative relationship between, on the one hand the higher exhaled NO and circulating concentrations of bioactive NO products, and conversely the higher brain blood flow in Tibetans compared with Andeans, cannot be provided, several studies nevertheless support this notion.

First, in Lhasa at 3,658 m, submaximal exercise increased mean blood flow velocity in the internal carotid artery of Tibetan and Han Chinese subjects (Huang et al, 1992). At peak exercise levels, the Tibetans sustained the increase in flow velocity, whereas the Han did not. Across all exercise levels, up to and including peak effort, Tibetans demonstrated a greater increase in internal carotid artery flow velocity relative to resting value than did Han subjects.

Second, Norcliffe et al (2005) showed that Andeans at altitude have a smaller cerebral vasodilatory response to hypoxia and a larger cerebral vasoconstrictive response to hypocapnia under hypoxia compared with the same subjects shortly after arriving at sea level, indicating that the cerebrovascular responses are impaired at altitude. These authors suggested that an impaired release of vasoactive mediators, such as NO, at altitude may account for the decline of vasodilatation on hypoxia and for the increase of vasoconstriction on hypocapnia under hypoxia.

Third, Appenzeller et al (2006) demonstrated that Andeans had an insignificant response of CBF on giving a NO donor, whereas Ethiopians, who are well adapted to the high altitude, showed a significant cerebral vascular response to exogenous NO (Beall, 2006). The authors described the greater CBF response on NO administration in Ethiopians as proof of fitness for life at altitude, whereas Andeans lacked this fitness for life at altitude, and are in fact maladapted to the high altitude.

It is thus possible that in Andeans the role for NO to contribute to an increase in brain blood flow in light of chronic hypoxia is much less developed, or possibly annihilated (Appenzeller et al, 2006).

Transcranial Doppler Flow Velocity Measurements in Altitude Populations

In 6 of the 10 reports that were considered in this study, noninvasive transcranial Doppler flow velocity measurements were used as an index of CBF. To study Vmca data in various groups, the perfusion territory and the diameter of the mca should be comparable. Genetic differences between the Andean and Himalayan populations in the perfusion territory as well as in the width of the mca are possible confounding factors for the value of Vmca in our study. Unfortunately, to our knowledge, no studies are available that measured either the diameter of the mca or its perfusion territory in these populations.

However, a study in the Himalayas (Huang et al, 1992) showed that the diameter of the internal carotid artery, as measured in Tibetans and in Han Chinese, was similar. Also, Jansen et al (2007) studied Vmca in Sherpas who resided for several years at low altitude (1,300 m), and found no difference with a sea-level control group. Moreover, CBF values as measured in Andeans (Sørensen et al, 1974; Marc-Vergnes et al, 1974), as well as Vmca values that were also measured in Andeans (Appenzeller et al, 2004, 2006; Claydon et al, 2005) were all 18% to 20% lower compared with sea-level standard values. Taken together, we interpret the Vmca values in the two populations as being proportional to their CBF values.

Clinical Relevance

Andeans suffer from Chronic Mountain Sickness (CMS), with symptoms of migraine and lethargia, and signs of increased pulmonary artery pressure. Increased hematocrit and low NO availability have been implicated in the origin of CMS. However, CMS is relatively rare in native Tibetans who live at similar altitudes.

Migraine with aura was reported to have a 24% to 32.2% incidence in adult males in Cerro de Pasco (4,300 m) who had high hemoglobin levels and increased CMS scores (Appenzeller et al, 2005). Some of them had defective CO2 reactivity and defective cerebral vasodilatation in response to NO (Appenzeller et al, 2004, 2006).

Recent studies have shown that long-term stay of lowlanders at high altitude is associated with increased risk of thromboembolic stroke. In these studies, polycythemia was the only common risk factor (Jha et al, 2002; Niaz and Nayyar, 2003; Schobersberger et al, 2005). A study in the Andean high-altitude population of Cuzco (3,380 m) showed a stroke prevalence ratio, which was similar as in the North-American age adjusted population (Jaillard et al, 1995). Remarkably, the Andeans showed a higher incidence of thromboembolic stroke, which was associated with polycythemia, whereas, the North American population had a higher frequency of hemorrhagic stroke. As in developing countries, the stroke incidence is normally found to be lower when compared with developed countries, it would imply an additional thromboembolic stroke risk in the Andean high-altitude population. This is in sharp contrast with a lower mortality from stroke in subjects living permanently at high altitude in Switzerland as has been reported recently (Faeh et al, 2009).

These data suggest that the Andean model of adaptation to the hypoxia of high altitude with polycythemia and an altered brain blood flow regulation may carry an increased risk for developing thromboembolic stroke and an increased incidence of migraine, in contrast with the Himalayan model of adaptation.

Conclusions

Field studies have demonstrated that Himalayan populations have substantially higher brain blood flow than Andean populations. The difference exists after correction for the higher hct in both populations. Increased NO availability in Himalayans, and/or hypo-metabolism of the brain of Andeans may have a role to explain this difference. The Andean model of adaptation, in contrast with the Himalayan model, may carry an increased risk for stroke from the high hematocrit, and predisposes for brain symptoms of CMS, which are related to altered CBF responses. Further work on adaptive mechanisms against oxygen limitations in the brain should include reference to the different patterns of brain blood flow regulation that possibly exist in high-altitude populations.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Appenzeller O, Claydon VE, Gulli G, Qualls C, Slessarev M, Zenebe G, Gebremedhin A, Hainsworth R. Cerebral vasodilatation to exogenous NO is a measure of fitness for life at altitude. Stroke. 2006;37:1754–1758. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000226973.97858.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appenzeller O, Minko T, Qualls C, Pozharov V, Gamboa J, Gamboa A, Wang Y. Migraine in the Andes and headache at sea level. Cephalalgia. 2005;25:1117–1121. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.00973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appenzeller O, Passino C, Roach R, Gamboa J, Gamboa A, Bernardi L, Bonfichi M, Malcovati L. Cerebral vasoreactivity in Andeans and headache at sea level. J Neurol Sci. 2004;219:101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2003.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beall CM. Andean, Tibetan and Ethiopian patterns of adaptation to high-altitude hypoxia. Integr Comp Biol. 2006;46:18–24. doi: 10.1093/icb/icj004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beall CM. Two routes to functional adaptation: Tibetan and Andean high-altitude natives. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104:8655–8666. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701985104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beall CM, Brittenham GM, Strohl KP, Blangero J, Williams-Blangero S, Goldstein MC, Decker MJ, Vargas E, Villena M, Soria R, Alarcon AM, Gonzales C. Hemoglobin concentration of high-altitude Tibetans and Bolivian Aymara. Am J Physic Anthropol. 1998;106:385–400. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199807)106:3<385::AID-AJPA10>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beall CM, Laskowski D, Strohl KS, Soria R, Villena M, Vargas E, Alarcon AM, Gonzales C, Erzurum SC. Pulmonary nitric oxide in mountain dwellers. Nature. 2001;414:4111–4112. doi: 10.1038/35106641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MM, Wade JPH, Marshall J. Fundamental importance of arterial oxygen content in the regulation of cerebral blood flow in man. Brain. 1985;108:81–93. doi: 10.1093/brain/108.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claydon VE, Norcliffe LJ, Moore JP, Rivera M, Leon-Velarde F, Appenzeller O, Hainsworth R. Cardiovascular responses to orthostatic stress in healthy altitude dwellers, and altitude residents with chronic mountain sickness. Exp Physiol. 2005;90:103–110. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2004.028399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalsgaard MK. Fuelling cerebral activity in exercising man. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:731–750. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duplain H, Sartori C, Lepori M, Egli M, Allemann Y, Nicod P, Scherrer U. Exhaled nitric oxide in high-altitude pulmonary edema: role in the regulation of pulmonary vascular tone and evidence for a role against inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:221–224. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.1.9908039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erzurum SC, Ghosh S, Janocha AJ, Xu W, Bauer S, Bryan NS, Tejero J, Hemann C, Hille R, Stuehr DJ, Feelisch M, Beall CM. Higher blood flow and circulating NO products offset high-altitude hypoxia among Tibetans. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104:17593–17598. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707462104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faeh D, Gutzwiller F, Bopp M. Lower mortality from coronary heart disease and stroke at higher altitudes in Switzerland. Circulation. 2009;120:495–501. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.819250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grocott MPW, Martin DS, Levett DZH, McMorrow R, Windsor J, Montgomery HE. Arterial blood gases and oxygen content in climbers on Mount Everest. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:140–149. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen L, Paulson OB, Smith RJ. Cerebral blood flow following normovolemic hemodilution in patients with high hematocrit. Ann Neurol. 1981;9:454–457. doi: 10.1002/ana.410090507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochachka PW, Clark CM, Brown WD, Stanley C, Stone CK, Nickles RJ, Zhu GG, Allen PS, Holden JE. The brain at high altitude: hypometabolism as a defense against chronic hypoxia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1994;14:671–679. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1994.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochachka PW, Clark CM, Monge C, Stanley C, Brown WD, Stone CK, Nickles RJ, Holden JE. Sherpa brain glucose metabolism and defense adaptations against chronic hypoxia. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81:1355–1361. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.3.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoit BD, Dalton ND, Erzurum SC, Laskowski D, Strohl KS, Beall CM. Nitric oxide and cardiopulmonary hemodynamics in Tibetan highlanders. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:1796–1801. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00205.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SY, Moore LG, McCullough RE, McCullough RG, Micco AJ, Fulco C, Cymerman A, Manco-Johnson M, Weil JV, Reeves JT. Internal carotid and vertebral arterial flow velocity in men at high altitude. J Appl Physiol. 1987;63:395–400. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.63.1.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SY, Sun S, Droma T, Zhuang J, Tao JX, McCullough RG, McCullough RE, Micco AJ, Reeves JT, Moore LG. Internal carotid arterial flow velocity during exercise in Tibetan and Han residents of Lhasa (3,658 m) J Appl Physiol. 1992;73:2638–2642. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.6.2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaillard AS, Hommel M, Mazetti P. Prevalence of stroke at high altitude (3380 m) in Cuzco, a town of Peru. Stroke. 1995;26:562–568. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.4.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen GFA, Krins A, Basnyat B. Cerebral vasomotor reactivity at high altitude in humans. J Appl Physiol. 1999;86:681–686. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.2.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen GFA, Krins A, Basnyat B, Bosch A, Odoom JA. Cerebral autoregulation in subjects adapted and not adapted to high altitude. Stroke. 2000;31:2314–2318. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.10.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen GFA, Krins A, Basnyat B, Ince C. Role of the altitude level on cerebral autoregulation in residents at high altitude. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103:518–523. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01429.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha SK, Anand AC, Sharma V, Kumar N, Adya CM. Stroke at high altitude: Indian Experience. High Alt Med Biol. 2002;3:21–27. doi: 10.1089/152702902753639513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser B, Hoppeler H, Desplanches D, Marconi C, Broers B, Cerretelli P. Muscle ultrastructure and biochemistry of lowland Tibetans. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81:419–425. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.1.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasney JA, Jensen JB, Lassen NA. Cerebral blood flow does not adapt to sustained hypoxia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1990;10:759–764. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1990.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen PL, Hasselbalch SG, Hagemann LP, Olsen KS, Bøülow J, Holm S, Wildschiødtz G, Paulson OB, Lassen NA. Peristent resetting of the cerebral oxygen/glucose uptake ratio by brain activation: evidence obtained with the Kety-Schmidt technique. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1995;15:485–491. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1995.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marc-Vergnes J-P, Antezana G, Coudert J, Gourdin D, Durand J. Débit sanguin et métabolisme énergétique du cerveau et équilibre acido-basique du liquide céphalo-rachidien chez les résidents en altitude. J Physiol Paris. 1974;88:633–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milledge JS, Sørensen SC. Cerebral arteriovenous oxygen difference in man native to high altitude. J Appl Physiol. 1972;32:687–689. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1972.32.5.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller K, Paulson OB, Hornbein TF, Colier WN, Paulson AS, Roach RC, Holm S, Knudsen GM. Unchanged cerebral blood flow and oxidative metabolism after acclimatisation to high altitude. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22:118–126. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200201000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore LG. Comparative human ventilatory adaptation to high altitude. Resp Physiol. 2000;121:257–276. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(00)00133-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore LG, Zamudio S, Zhuang J, Sun S, Droma T. Oxygen transport in Tibetan women during pregnancy at 3658 m. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2001;114:42–53. doi: 10.1002/1096-8644(200101)114:1<42::AID-AJPA1004>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niaz A, Nayyar S. Cerebrovascular stroke at high altitude. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2003;13:446–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norcliffe LJ, Rivera-CH M, Claydon VE, Moore JP, Leon-Velarde F, Appenzeller O, Hainsworth R. Cerebrovascular responses to hypoxia and hypocapnia in high-altitude dwellers. J Physiol. 2005;566:287–294. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.086629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson OB, Parving H-H, Olesen J, Skinhøj E. Influence of carbon monoxide and of hemodilution on cerebral blood flow and blood gases in man. J Appl Physiol. 1973;33:111–116. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1973.35.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider A, Greene RE, Keyl C, Bandinelli G, Passino C, Spadacini G, Bonfichi M, Arcaini L, Marcovati L, Boiardi A, Feil P, Bernardi L. Peripheral arterial vascular function at altitude: sea level natives versus Himalayan high-altitude natives. J Hypertens. 2001;19:213–222. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200102000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schobersberger W, Hoffmann G, Gunga H-C. Interaktionen von Hypoxie und Hämostase – Hypoxie als prothrombotischer Faktor in der Höhe. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2005;155:157–162. doi: 10.1007/s10354-005-0163-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severinghaus JW.2001Cerebral circulation at altitude High Altitude, An Exploration of Human Adaptation(Hornbein TF, Schoene RB, eds),New York, Basel: Marcel Dekker; 343–375. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen SC, Lassen NA, Severinghaus JW, Coudert J, Paz Zamora M. Cerebral glucose metabolism and cerebral blood flow in high-altitude residents. J Appl Physiol. 1974;37:305–310. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1974.37.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuber T, Sartori C, Salinas Salmon C, Hutter D, Thalmann S, Turini P, Jayet P-Y, Schwab M, Sartori-Cucchia C, Villena M, Scherrer U, Allemann Y. Respiratory nitric oxide and pulmonary artery pressure in children of Aymara and European ancestry at high altitude. Chest. 2008;134:996–1000. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S, Oliver-Pickett C, Ping Y, Micco AJ, Droma T, Zamudio S, Zhuang J, Huang S-J, McCullough RG, Cymerman A, Moore LG. Breathing and brain blood flow during sleep in patients with chronic mountain sickness. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81:611–618. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.2.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winslow RE. The role of hemoglobin oxygen affinity in oxygen transport at high altitude. Respir Physiol. 2007;158:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood SC, Appenzeller O, Appenzeller P. Transcranial measurement of cerebral blood flow in sojourners and natives at high altitudes. Ann Sports Med. 1988;4:289–293. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang DD, Li SH. Optical dating of Tibetan human hand- and footprints: an implication for the palaeoenvironment of the last glaciation of the Tibetan plateau. Geophys Res Lett. 2002;29:1072–4. [Google Scholar]