Abstract

Background

Closed-suction drainage is commonly used for prevention of postoperative hematoma and associated neurologic compromise after lumbar decompression, but it remains unclear whether suction drainage reduces postoperative complications.

Questions/purposes

We evaluated the efficacy of closed-suction drainage in single-level lumbar decompression surgery.

Patients and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 560 patients who underwent single-level lumbar decompression or discectomy. We routinely used closed-suction drainage in all spinal surgeries until July 2003, and thereafter, we did not use drains in single-level lumbar decompression surgery. These two groups (298 patients in the group that received drains, 262 in the group that did not receive drains) were compared for rates of wound infection and epidural hematoma.

Results

Mean operating time (55 versus 56 minutes) and intraoperative blood loss (64 versus 57 mL) were not different between the two groups. None of 560 patients had a wound infection requiring surgical intervention. The rate of postoperative hematoma was 0.7% in the group that received drains (two of 298 patients) and 0% in the group that did not receive drains (zero of 262 patients).

Conclusions

In this study, the risk of wound infection and hematomas in single-level lumbar decompression surgery was not influenced by use of a drain. The use of postoperative wound drainage in patients with potential risk for epidural bleeding in situations such as multiple-level decompression, instrumentation surgery, anticoagulant therapy, trauma, and tumors or metastases needs additional study.

Level of Evidence

Level III, prognostic study. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Closed-suction drainage traditionally has been used to prevent postoperative hematoma. Also, considering hematoma provides an excellent culture medium for infections, evacuation of hematoma is believed advisable to prevent postoperative infections. However, the current orthopaedic literature has not shown an advantage for the use of drains in hip and knee arthroplasty [10, 12]. In addition, drains have not been shown to provide benefit with respect to rates of infection and hematomas in fracture or trauma surgeries [7, 15].

In spine surgeries, postoperative epidural hematomas and wound infections can have devastating neurologic sequences [3, 8, 9]. The quoted incidence of postoperative symptomatic epidural hematoma occurring after all spinal procedures requiring surgical intervention ranges from 0.2% to 2.9% [1, 6, 13]. Closed-suction drainage is believed effective in preventing these complications in spine surgery, but only a few studies have addressed the efficacy of drain use. It remains unclear whether suction drainage reduces postoperative complications.

We believe closed-suction drainage confers no benefit after single-level decompressive surgery in the lumbar spine. We compared the incidence of (1) postoperative wound infection and (2) epidural hematoma formation in single-level lumbar decompression surgeries with and without the use of prophylactic closed-suction drainage.

Patients and Methods

We reviewed 560 consecutive patients who underwent single-level lumbar laminoplasty (medial facetectomy) or discectomy during a 5-year period (between January 2001 and October 2005). Those who underwent multilevel decompression and/or fusion surgery were not included in this study. No patients were lost for observation. There were 360 males and 200 females with a mean age of 46 years. The current study was based on a retrospective analysis of a prospective database, which included patient age and gender, diagnosis, type of surgery, operating time, intraoperative blood loss, revision surgery for postoperative complications, and other clinical data. We routinely placed closed-suction drainage in all spinal surgeries until July 2003 and thereafter did not use drains in the case of single-level lumbar decompression surgery. After surgery, the drain was removed when the amount of bleeding did not exceed 50 mL per day.

Based on the use of closed-suction drainage, the patients were divided into two groups: those who received drains and those who did not receive drains. The group that received drains had 298 patients including 190 males and 108 females with a mean age of 44 years. The group that did not receive drains had 262 patients including 168 males and 94 females with a mean age of 48 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of the groups

| Parameter | Group with drains | Group without drains |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 298 | 262 |

| Male:female | 190:108 | 168:94 |

| Mean age (years) | 44 | 48 |

| Mean operating time (minutes) | 55 | 56 |

| Mean estimated blood loss (mL) | 64 | 57 |

Until December 2002, we used prophylactic antibiotics intravenously for 5 to 7 days postoperatively for patients undergoing lumbar spine surgeries. In January 2003, based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guideline, we revised the protocol of antimicrobial prophylaxis (AMP). In the revised AMP protocol, antibiotics were given only the day of surgery. A first-generation cephalosporin was administered unless the patient had a history of a significant allergy such as anaphylactic shock, systemic skin eruption, or toxic liver dysfunction. Therefore, the patients in the group that did not receive drains received antibiotics only the day of surgery, but either AMP protocol was used for those in the group that did receive drains. The CDC-guideline-based AMP protocol did not increase the incidence of postoperative infections [5].

The surgery was performed with the patient under hypotensive anesthesia in which systolic blood pressure was kept to less than 90 mm Hg. Before wound closure, blood pressure was returned to normotension; substantial epidural bleeding, if any, was stopped using electrocautery. After adequate hemostasis, fibrin glue was applied on the epidural space (Fig. 1). As we used fibrin glue in all patients, the bias between the group that received drains and the group that did not receive drains should be minimal in terms of the effect of fibrin glue use.

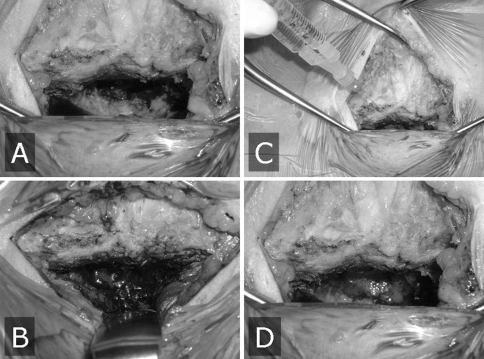

Fig. 1A–D.

Hemostasis and wound closure are shown in these images. (A) The surgical site under hypotensive anesthesia (right hand is caudal direction), and (B) after return to normotension, (C) application of fibrin glue, and (D) the surgical site sealed with fibrin glue are shown.

The rate of postoperative complications (epidural hematomas, wound infections) requiring surgical intervention was compared between the two groups using a chi square test. The level of significance was set at p = 0.05.

Results

Mean operating time (55 and 56 minutes) and intraoperative blood loss (64 and 57 mL) were similar in both groups.

There was no difference in the risk of wound infection as a result of the use or avoidance of postoperative closed-suction drainage in these two groups of patients. None of the 560 patients incurred wound infections requiring surgical intervention.

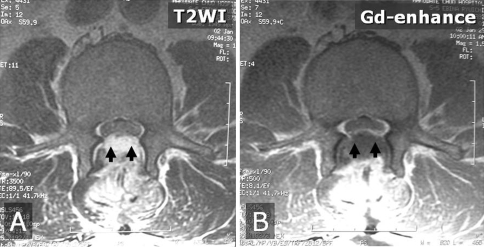

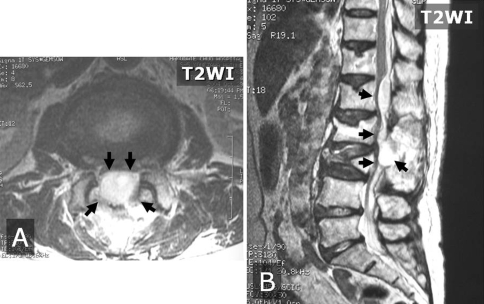

There was no significant difference in hematoma formation when the two groups were compared. Two patients in the group receiving closed-suction drainage had postoperative epidural hematomas develop causing neurologic compromise and both underwent surgical evacuation (Figs. 2, 3). Thus, the overall rate of postoperative epidural hematoma was 0.4% in the series, and the rate of postoperative hematoma was 0.7% in the group that received drains (two of 298 patients) and 0% in the group that did not receive drains (zero of 262 patients). One patient was a 52-year-old man who had a herniated disc combined with spinal stenosis at L3/L4 and underwent medial facetectomy and discectomy. As he had an unknown bleeding diathesis, the intraoperative blood loss reached 500 mL. Closed-suction drainage was used in this patient. Although the drain was kept in place and in working order, neurologic deterioration was observed 2 days after the initial surgery. T2-weighted and gadolinium-enhanced MR images (Fig. 2) showed hematoma formation at the epidural space between L2 and L4. Immediately after the MRI, L2 laminectomy and hematoma evacuation were performed. The patient achieved complete neurologic recovery. In the second case, the patient was a 79-year-old woman who had L2/L3 spinal stenosis attributable to L3 osteoporotic vertebral collapse. She had comorbidities including osteoporosis and hypertension. At the initial surgery, a medial facetectomy was performed for L2/L3 spinal stenosis. Intraoperative blood loss was 150 mL. Closed-suction drainage was used in this patient. Although the drain was kept in place and in working order, neurologic deterioration developed on the day of surgery. Axial and sagittal T2-weighted MR images showed hematoma formation at the epidural space between T12 and L3. On the day of the initial surgery, a wide laminectomy was performed from T12 to L2 to evacuate the hematoma. The patient achieved complete neurologic recovery.

Fig. 2A–B.

(A) T2-weighted and (B) gadolinium-enhanced MR images show hematoma formation (arrows) at the epidural space between L2 and L4 in our first study patient with a postoperative epidural hematoma.

Fig. 3A–B.

(A) Axial and (B) sagittal T2-weighted MR images show hematoma formation (arrows) at the epidural space between T12 and L3 in our second study patient with a postoperative epidural hematoma.

Discussion

Closed-suction drainage traditionally has been used in patients having lumbar spine surgery to prevent postoperative complications, including epidural hematoma and associated neurologic compromise. However, several studies have questioned the benefit of drain placement in patients having lumbar spine surgery [2, 13]. We compared the rate of postoperative complications (wound infections, epidural hematomas) in single-level lumbar decompression surgeries with and without the use of prophylactic closed-suction drainage.

Several limitations to our study should be addressed. The retrospective design and the rarity of the complication limit this study. A study of 560 patients was underpowered to fully investigate the rare occurrence of these complications. Tenney et al. [14] calculated 2000 patients having spinal surgery would need to be entered in a study to ensure statistical significance at 5%, assuming prophylaxis was 80% effective in terms of preventing postoperative wound infections. Dimick et al. [4] also determined 5036 patients would need to be enrolled to show a reduction in the infection rate from 2% to 1%. Clearly, the magnitude of this number indicates a clinical trial is unlikely. The rare occurrence of these complications precludes any other reasonable study design unless there is a multicenter effort.

Although our study was retrospective, we reviewed a large number of patients undergoing single-level laminoplasty to evaluate the efficacy of closed-suction drainage. None of the 560 patients incurred wound infection requiring surgical intervention; the rate of postoperative epidural hematoma was 0.7% in the group that received drains and 0% in the group that did not receive drains. These results suggest the risk of postoperative complications did not increase without placement of closed-suction drainage.

Payne et al. [11] conducted a prospective randomized controlled study to determine the indications for closed-suction drainage after single-level lumbar laminectomy without fusion. They randomized 200 operative candidates into two groups based on the presence or absence of a drain and found two of 103 patients with a drain and one of 97 patients without a drain had wound infections develop. They concluded closed-suction drainage provided no benefit with respect to rates of infection and wound healing in lumbar laminectomy without fusion.

Brown and Brookfield [2] evaluated the efficacy of closed-suction drainage in extensive lumbar spine surgeries, including multilevel decompression and instrumentation surgery. They prospectively randomized 83 patients into “drain” and “no drain” groups. They also reported use or no use of a closed-suction drain did not result in infection or hematoma even in extensive lumbar spine surgery.

The decision to use or not use a closed-suction drain after complex lumbar spine surgery should be left to the surgeon’s discretion. Awad et al. [1] analyzed the records of 14,932 patients undergoing spinal surgeries to identify the risk factors of postoperative spinal epidural hematoma. They showed more than five operative levels, anemia (< 10 g/dL), and excessive blood loss (> 1 L) increased the risk of epidural hematoma formation. Although well-controlled anticoagulation was not associated with formation of a symptomatic epidural hematoma, they found the patients who were coagulopathic from the procedure or from overmedication with anticoagulants had a high risk of this complication. Thus, considering these factors, our findings should be applied only to single-level laminoplasty or discectomy. The use of postoperative wound drainage in patients with potential risk of epidural bleeding in situations such as multiple-level decompression, instrumentation surgery, anticoagulant therapy, trauma, and tumors or metastases needs additional study.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

References

- 1.Awad JN, Kebaish KM, Donigan J, Cohen DB, Kostuik JP. Analysis of the risk factors for the development of post-operative spinal epidural haematoma. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:1248–1252. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B9.16518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown MD, Brookfield KF. A randomized study of closed wound suction drainage for extensive lumbar spine surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004;29:1066–1068. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200405150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Lauro L, Poli R, Bortoluzzi M, Marini G. Paresthesias after lumbar disc removal and their relationship to epidural hematoma: report of two cases. J Neurosurg. 1982;57:135–136. doi: 10.3171/jns.1982.57.1.0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dimick JB, Lipsett PA, Kostuik JP. Spine update: antimicrobial prophylaxis in spine surgery: basic principles and recent advances. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:2544–2548. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200010010-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanayama M, Hashimoto T, Shigenobu K, Oha F, Togawa D. Effective prevention of surgical site infection using a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guideline-based antimicrobial prophylaxis in lumbar spine surgery. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:327–329. doi: 10.3171/spi.2007.6.4.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kou J, Fischgrund J, Biddinger A, Herkowitz H. Risk factors for spinal epidural hematoma after spinal surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27:1670–1673. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200208010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lang GJ, Richardson M, Bosse MJ, Greene K, Meyer RA, Jr, Sims SH, Kellam JF. Efficacy of surgical wound drainage in orthopaedic trauma patients: a randomized prospective trial. J Orthop Trauma. 1998;12:348–350. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199806000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawton MT, Porter RW, Heiserman JE, Jacobowitz R, Sonntag VK, Dickman CA. Surgical management of spinal epidural hematoma: relationship between surgical timing and neurological outcome. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:1–7. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.83.1.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morse K, Weight M, Molinari R. Extensive postoperative epidural hematoma after full anticoagulation: case report and review of the literature. J Spinal Cord Med. 2007;30:282–287. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2007.11753938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parker MJ, Roberts CP, Hay D. Closed suction drainage for hip and knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:1146–1152. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.86B8.14839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Payne DH, Fischgrund JS, Herkowitz HN, Barry RL, Kurz LT, Montgomery DM. Efficacy of closed wound suction drainage after single-level lumbar laminectomy. J Spinal Disord. 1996;9:401–403. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199610000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ritter MA, Keating EM, Faris PM. Closed wound drainage in total hip or total knee replacement: a prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:35–38. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199401000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scuderi GJ, Brusovanik GV, Fitzhenry LN, Vaccaro AR. Is wound drainage necessary after lumbar spinal fusion surgery? Med Sci Monit. 2005;11:CR64–CR66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tenney JH, Vlahov D, Salcman M, Ducker TB. Wide variation in risk of wound infection following clean neurosurgery: implications for perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:243–247. doi: 10.3171/jns.1985.62.2.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tjeenk RM, Peeters MP, Ende E, Kastelein GW, Breslau PJ. Wound drainage versus non-drainage for proximal femoral fractures: a prospective randomised study. Injury. 2005;36:100–104. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]