Abstract

Background

The Internet should, in theory, facilitate access to peer-reviewed scientific articles for orthopaedic surgeons in low-income countries (LIC). However, there are major barriers to access, and most full-text journal articles are available only on a subscription basis, which many in LIC cannot afford. Various models exist to remove such barriers. We set out to examine the potential, and reality, of journal article access for surgeons in LIC by studying readership patterns and journal access through a number of Internet-based initiatives, including an open access journal (“PLoS Medicine”), and programs from the University of Toronto (The Ptolemy Project) and World Health Organization (WHO) (Health InterNetwork Access to Research Initiative [HINARI]).

Questions/purposes

Do Internet-based initiatives that focus on peer-reviewed journal articles deliver clinically relevant information to those who need it? More specifically: (1) Can the WHO’s program meet the information needs of practicing surgeons in Africa? (2) Are healthcare workers across the globe aware of, and using, open access journals in a manner that reflects global burden of disease (GBD)?

Methods

We compared actual Ptolemy use to HINARI holdings. We also compared “PLoS Medicine” readership patterns among low-, middle-, and high-income regions.

Results

Many of the electronic resources used through Ptolemy are not available through HINARI. In contrast to higher-income regions, “PLoS Medicine” readership in Africa is proportional to both the density of healthcare workers and the GBD there.

Conclusions

Free or low-cost Internet-based initiatives can improve access to the medical literature in LIC. Open access journals are a key component to providing clinically relevant literature to the regions and healthcare workers who need it most.

Introduction

Access to peer-reviewed scientific articles for orthopaedic surgeons in low-income countries (LIC) should, in principle, be greatly facilitated by the Internet. However, most full-text journal articles are available only on a subscription basis, so surgeons in LIC are excluded not only because of limited Internet connectivity (www.internetworldstats.com) or savvy [6, 19], but also because they and their institutions cannot afford subscriptions. Open access is the most rapidly growing area of medical publishing, and a move to open access would have the beneficial side effect of removing major cost barriers to access for surgeons in LIC. The large unmet needs for surgical information in LIC, particularly around trauma, have been previously documented in this journal [11, 12]. While the Internet offers many free sources of orthopaedic information that may be useful to healthcare workers in LIC, our investigations focused on three specific programs that provide access to peer-reviewed journal articles.

In 2001, The University of Toronto initiated The Ptolemy Project, an effort to provide electronic medical information to individual surgeons in Africa (most of whom access the Internet after hours from their own homes or Internet cafes) [2, 19]. An advantage of basing such an initiative out of a major academic institution is the breadth of resources; the University of Toronto Library contains nearly 15,000 full-text journals as well as thousands of full-text medical textbooks. A unique aspect of Ptolemy is the ability to monitor the reading patterns of the surgeons participating in the project [2].

In 2002, the World Health Organization (WHO) and a group of commercial journal publishers began the Health InterNetwork Access to Research Initiative (HINARI) to provide free or low-cost access to a broad range of medical journals to institutions (medical libraries) in LIC. According to the WHO web site, the project has grown to over 6400 journal titles available to health institutions in 108 countries, areas, and territories “benefiting many thousands of health workers and researchers, and in turn, contributing to improved world health” [25].

Open access publishing began in 1999 with the BioMed Central group of journals (now owned by Springer, who also publish CORR) and is the fastest growing sector in biomedical journal publishing. According to the Directory of Open Access Journals, there are now over 4000 open access journals, representing about 16% of the approximate 25,000 peer-reviewed academic journals in existence [13]. A team of scientists and physicians founded the Public Library of Science (PLoS) in 2000 as a nonprofit endeavor “committed to making the world’s scientific and medical literature a public resource” [15]. One obvious advantage of open access publishing is that the articles are available free for anyone to read, which could dramatically improve access to medical literature to LIC healthcare workers and would make projects like HINARI and Ptolemy unnecessary in their current forms.

We asked whether these various Internet-based initiatives are successful at providing access to clinically relevant full-text journal articles in LIC. First, could the resources offered by HINARI meet the information needs of practicing surgeons in Africa, as represented by Ptolemy users? Second, how well do healthcare workers in LIC currently use “PLoS Medicine” compared with their counterparts in middle- and high-income regions?

Materials and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed readership patterns based on Internet log file analysis. To answer the first question, we used log files for full text downloads by 400 users of the Ptolemy library, surgeons in Africa, between 2003 and 2009. To answer the second question, we used anonymous log files from the “PLoS Medicine” web site, which detail the top 500 web pages viewed from each region of the world between September 14, 2008 and September 13, 2009.

The first question required a baseline understanding of what surgeons in LIC were reading. Therefore, we analyzed the reading patterns of registered Ptolemy users, dividing the 2047 unique journal titles accessed in the study period into most, middle, and least frequently accessed journals. These samples included the top 200 most frequently used journals, the middle 200 (accessed 5-7 times), and a random sample of the bottom 200 (accessed only once). Journals from these three groups were checked for inclusion on the list of journals available through HINARI [25]. Journal impact factors were compared for the three subsamples. Statistical significance was determined using t-tests (p < 0.05).

The second question regarding open access use compared readership patterns among LIC such as in Africa, high-income countries (HIC) such as in Europe, and a mixture of middle-income countries (MIC) with HIC such as in the Americas. Due to the nature of the available data from “PLoS Medicine” and the WHO, we were unable to analyze geographic regions more specifically than Africa, Europe, or the Americas. To evaluate whether clinically relevant information is reaching the regions that need it most, each full-text “PLoS Medicine” article among the top 500 page views per region was categorized according to the WHO’s Global Burden of Disease (GBD) categories as follows: (I) communicable diseases, maternal and perinatal conditions and nutritional deficiencies; (II) noncommunicable conditions; and (III) injuries. A fourth category, “other,” was implemented to account for those articles that could not be mapped directly to a GBD disease or condition [23].

We compared the number of articles viewed from “PLoS Medicine” within each region to the regional population, to the regional burden of disease expressed as disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and to the number of healthcare workers in the region [24]. We compared the proportions of articles downloaded within each region with the proportion of burden of disease (expressed as DALYs) borne by the population in that region [23].

Specific questions addressed by our analyses included the following: Did HINARI provide access to a large random sample of the journals accessed by Ptolemy users? Did the number or topic of “PLoS Medicine” articles read in Africa reflect the disease burden in the region? Did it reflect the size of the healthcare workforce? And how did it compare to similar comparisons in middle and high-income regions? Because all questions concerned simple proportions, statistical analysis was by chi-squared and T-tests with a p value of < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

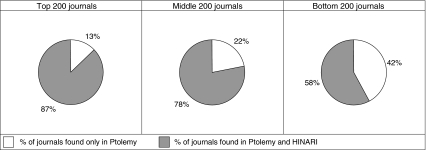

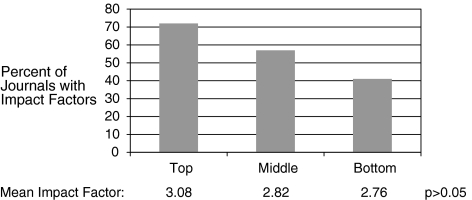

Of the journal titles used through Ptolemy by practicing surgeons, 13% of heavily used journals, 22% of medium use journals, and 42% of occasionally used journals were not available through HINARI (Fig. 1). We observed a small and statistically insignificant trend (p > 0.05) toward a higher impact factor among the most frequently accessed journals (Fig. 2). This trend was not strong with the average impact factor of the low use journals being 2.76 compared with only 3.08 for the 200 most frequently used journals. Technique papers and clinical reviews were popular with Ptolemy users; journals of this type are clinically useful but tend not to be cited as often in later publications and therefore generally garner a lower impact factor score [20]. Impact factor is not synonymous with quality. Many worthwhile orthopaedic journals have relatively low impact factors, similar to those least used clinical journals accessed through Ptolemy. The lack of these journals in HINARI may be limiting access to high quality and necessary clinical information. Impact factor should never be a measure of what clinicians need to read.

Fig. 1.

Journals most frequently accessed by Ptolemy users, surgeons in Africa, were almost always (87%) available through the WHO’s HINARI project, but less frequently used journals were often (42%) not available through HINARI.

Fig. 2.

The mean impact factors of journals accessed through Ptolemy were statistically different, but for practical purposes very close, in all three of the journal subsamples.

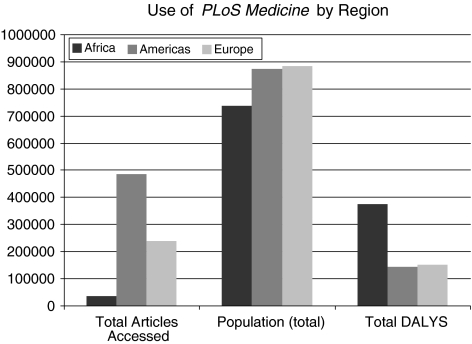

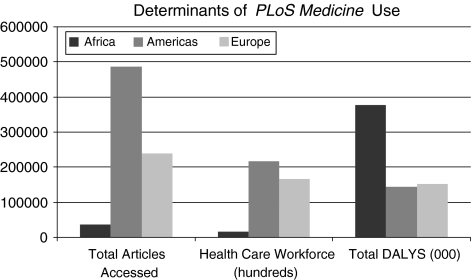

The total number of “PLoS Medicine” articles downloaded in Africa was much smaller (36,000) than the number downloaded in the Americas or Europe (486,000 and 238,000, respectively). This is despite the fact that the regions are similar in population, and Africa has a much higher burden of disease overall (Fig. 3). However, when the number of articles downloaded was compared with the number of healthcare workers in the region, we noted 2.18 article downloads per healthcare worker in Africa, 2.24 articles per healthcare worker in the Americas, and only 1.43 articles per healthcare worker in Europe. While the number of articles per healthcare worker in America was higher (p < 0.001) than that in Africa, the difference is probably not meaningful when we consider the overall use of this open access resource in proportion to the number of healthcare workers who might want to use it (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

The total number of PLoS Medicine articles read in Africa was small compared with that in Europe or the Americas, despite similar regional population (1000s) and a larger regional disease burden in Africa (1000s of disability-adjusted life-years [DALYs]).

Fig. 4.

The total number of PLoS Medicine articles read in Africa seemed more appropriate when compared with the regional healthcare workforce (100s) instead of the regional disease burden (1000s of disability-adjusted life-years [DALYs]).

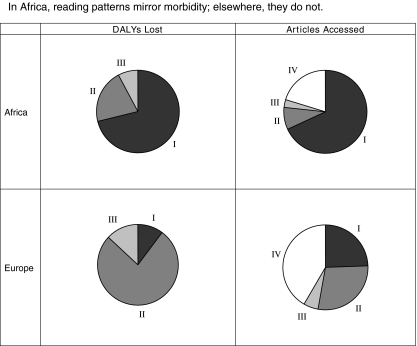

The topics of articles downloaded from “PLoS Medicine” in Africa correlated with the specific burden of disease in that continent with a preponderance of reading about communicable disease topics (Fig. 5). By contrast, the reading patterns in Europe and in the Americas did not correspond to the burden of disease in these more developed regions. A far greater proportion of articles read in Europe and the Americas were on nonclinical topics (eg, healthcare systems, health reform in the United States, medicolegal issues). Among clinical topics, Europeans and Americans read less about chronic diseases and substantially less about injury than the burden of noncommunicable conditions in their own regions would merit.

Fig. 5.

There was close correspondence between disease burden and readership in Africa compared with gross disproportion between disease burden and articles read in Europe. (I = Communicable diseases, II = Noncommunicable conditions, III = Injuries, IV = Nonclinical topics).

Discussion

We wanted to know how far Internet-based initiatives have come, and how open access has fared, in meeting the information needs of surgeons in LIC. We found that HINARI has come a very long way with a large library accessed with increasing frequency. However, we found that surgeons who have access to an even larger library (Ptolemy) make regular and repeated use of an even broader range of journals. If Ptolemy users were limited to only those higher impact factor journals available through HINARI, nearly 50% of their clinically relevant reading would be curtailed. We also found that the open access journal with the highest impact factor, “PLoS Medicine”, is widely read in Africa and is read in a manner that very closely mirrors the burden of disease in Africa. This is encouraging evidence that these Internet-based initiatives are achieving their goals of improving access to the peer-reviewed medical literature in LIC.

We draw attention to several limitations. First, in our comparison between Ptolemy and HINARI, we used the theoretical list of journals available through HINARI rather than confirming they were actually downloadable in Africa. Previous publications have shown 57% of the 150 HINARI journals with the highest impact factors could not actually be accessed from Peru in 2007 [21]. According to Smith’s survey of postgraduate doctors in four African teaching hospitals, only 24–73% of physicians were even aware of HINARI, and as many as 90% usually access the Internet from a café, but HINARI is only available through an institution [19].

Second, “PLoS Medicine” is a general medical journal, not a surgical journal. We recognize that the reading patterns of surgeons likely do not match those of internists and therefore our conclusions cannot be applied specifically to the information needs of orthopaedic surgeons. However, “PLoS Medicine” is the most frequently cited (and thus highest impact factor) open access journal, so we chose to analyze its readership. Surgically relevant public health, musculoskeletal and trauma topics are often well-represented in subscription-based general medical journals, and given the preponderance of musculoskeletal complaints to primary caregivers, we believe that journals such as “PLoS Medicine” should be covering musculoskeletal topics. For comparison, of the nearly 4000 papers published in “PLoS ONE” in 2009, only 21 specifically concern surgery [16]. Public Library of Science publications may not be overflowing with orthopaedic information, but there is a burgeoning of surgery- and orthopaedic-specific open access journals, some of which cater specifically to the needs of LIC [7].

A third limitation is the lack of quantitative data about additional free Internet-based sources of orthopaedic knowledge. Smith et al. found that across 333 postgraduate doctors in four African teaching hospitals, “90% had heard of PubMed, 78% of BMJ on line, 49% the Cochrane Library, 47% HINARI, and 19% BioMedCentral” [19]. Surgeons in low- or middle-income countries may need more basic information than that provided in peer-reviewed journals, but one survey of surgeons in LIC found that the most sought-after electronic resource was journal articles, while electronic textbooks were a distant second [4]. None the less, useful free Internet-based resources may include (but are not limited to) Wheeless [22], eMedicine [8], Global HELP [9], orthopaedic case discussion sites [14], or free patient information resources [1, 18]. These services are of variable value and quality, and most LIC surgeons we know are sophisticated enough to value peer-reviewed sources.

Language of publication is another limitation when assessing utility and accessibility of online medical resources. English has a wider dispersion than any other language and is commonly considered the lingua franca of the modern world, but the number of English speakers in various regions or countries is extremely difficult to define. “PLoS Medicine” readership data lumps North, Central and South America, but one might surmise that the greatest usage takes place in the English-speaking north. Likewise, though English is a common second language in Europe, preference for materials in one’s native language may explain the lower readership per healthcare worker in Europe.

While free access to peer-reviewed journals has been shown to provide clinically- and academically-relevant resources to surgeons in LIC [2, 6], substantial barriers of Internet connectivity and awareness must be addressed before healthcare workers will fully benefit from online resources. Obviously, development of local infrastructure will be necessary to improve the reliability of electricity and connectivity. In addition to HIC efforts such as those reviewed in this paper, other efforts may bridge the digital divide in the meantime. For instance, Global HELP (Health Education using Low-cost Publications) creates and distributes affordable health education materials, including PDFs, posters and CD libraries [9].

Medical publishing is a high value-add business. Two business models (and a number of hybrids) exist: the subscriber pays or the author pays. Open access, the author pays model, accounts for a very small minority of overall publishing. It is, however, the most rapidly growing publishing paradigm. The next decade will be interesting; will the publishing industry find a balance between placing the financial burden on the author or the subscriber, or will a tipping point be reached at which the entire industry moves toward open access?

Open access publishing has several advantages over the traditional subscription-based industry. For example, open access has the potential for wide and rapid dissemination of new findings. On the other hand, more traditional media may be perceived as having greater longevity, a higher impact factor with a higher profile editorial board, and a more exclusive readership. Currently, there seems to be a positive attitude among researchers regarding the idea of open access, and yet, this does not necessarily translate to an intention to publish one’s own research in an open access journal [10]. Open access does seem to increase the number of article downloads, but that does not translate into an increased rate of citation of those articles [5]. Based on the readership of Ptolemy users, we know surgeons in LIC read a wide variety of clinical journals when given the opportunity. For the time being, access to such a breadth of medical literature will rely on projects such as Ptolemy and HINARI that are able to legitimately provide free access to subscription-based journals. The scalability and expansion of Ptolemy-type projects has been previously addressed [2, 6].

The publishing field is moving toward open access, but nobody knows how quickly or completely open access journals will take over from subscriber-based journals. Within a specific open access journal, we have shown readership in Africa is as high as the Americas and higher than Europe when compared with the healthcare worker density and that the readership corresponds more closely to the burden of disease in Africa than in higher-income regions. The open access publishing model presents a substantial increase in the availability of research information in LIC, as long as healthcare workers are aware of the ever-growing free resources as catalogued on sites such as Directory of Open Access Journals [7]. Some authors may be hesitant to submit publications to newer, less well-known open access journals [10], so an alternative to simply creating new open access journals is to encourage already-existing, prestigious, subscription-based journals to move to some version of the open access model. Should open access take over the scientific publishing industry, initiatives like Ptolemy and HINARI will no longer be needed to bridge the gap in access to the body of published literature, but it is a double-edged sword. The ability of African surgeons to publish in the open access journals they read will only be maintained if the current enlightened policies regarding waiving author fees for papers from LIC can be systematically maintained [3, 17].

Acknowledgments

We thank “PLoS Medicine” for access to data.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

The present study involved the analysis of anonymized Internet log files that cannot be tracked to individual human subjects. All participants in the Ptolemy project have provided written consent for such use. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Toronto.

This work was performed at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

References

- 1.American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Your orthopaedic connection: Patient education library. Available at: http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/. Accessed April 2, 2010.

- 2.Beveridge M, Howard A, Burton K, Holder W. The Ptolemy project: a scalable model for delivering health information in Africa. BMJ. 2003;327:790–793. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7418.790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.BioMed Central. BioMed Central open access waiver fund. Available at: http://www.biomedcentral.com/info/authors/oawaiverfund/. Accessed November 24, 2009.

- 4.Burton K, Howard A, Beveridge M. Relevance of electronic health information to doctors in the developing world: results of the Ptolemy project’s internet-based health information study (IBHIS) World J Surg. 2005;29:1194–1198. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7938-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis PM, Lewenstein BV, Simon DH, Booth JG, Conolly MJL. Open access publishing, article downloads, and citations: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008;337:a568. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Derbew M, Beveridge M, Howard A, Byrne N. Building surgical research capacity in Africa: the Ptolemy project. PLoS Medicine. 2006;3:e305. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Directory of Open Access Journals. Available at: http://www.doaj.org/. Accessed March 10, 2010.

- 8.Gellman H, ed. eMedicine Orthopaedics. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/orthopedic_surgery. Accessed April 2, 2010.

- 9.Global HELP (Health Education using Low-cost Publications). Available at: http://www.global-help.org. Accessed April 2, 2010.

- 10.Mann F, Walter B, Hess T, Wigand RT. Open access publishing in science. ACM. 2009;52:135–139. doi: 10.1145/1467247.1467279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noordin S, Wright J, Howard A. Global access to literature on trauma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:2418–2421. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0375-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noordin S, Wright J, Howard A. Global relevance of literature on trauma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:2422–2427. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0397-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Open Access Scholarly Information Sourcebook (OASIS). Open access journals. Available at: http://www.openoasis.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=155&catid=78&Itemid=326. Accessed March 10, 2010.

- 14.Orthopaedic Trauma Association. OTA Discussion Forums. Available at: http://www.ota.org/discussion/index.html. Accessed April 2, 2010.

- 15.Public Library of Science. About PLoS. Available at: http://www.plos.org/about/index.html. Accessed October 10, 2009.

- 16.Public Library of Science. PLoS ONE. Available at: http://www.plosone.org/home.action. Accessed November 24, 2009.

- 17.Public Library of Science. Publication Fee FAQs. Available at: http://www.plos.org/about/faq.html#pubquest. Accessed November 24, 2009.

- 18.Sechrest RC. eOrthopod. Available at: http://www.eorthopod.com/. Accessed April 2, 2010.

- 19.Smith H, Bukirwa H, Mukasa O, Snell P, Adeh-Nsoh S, Mbuyita S, Honorati M, Orji B, Garner P. Access to electronic health knowledge in five countries in Africa: a descriptive study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:72. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The PLoS Medicine Editors. The impact factor game. It is time to find a better way to assess the scientific literature. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Villafuerte-Galvez J, Curioso W, Gayoso O. Biomedical journals and global poverty: is HINARI a step backwards? PLoS Medicine. 2007;4:e220. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wheeless CR, ed. Wheeless’ Textbook of Orthopaedics. Available at: http://www.wheelessonline.com. Accessed April 2, 2010.

- 23.World Health Organization. Global Burden of Disease (GBD). Available at: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/en/. Accessed October 10, 2009.

- 24.World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2006. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2006.

- 25.World Health Organization. Health InterNetwork Access to Research Initiative (HINARI). Available at: www.who.int/hinari/en/. Accessed October 23, 2009.