Introduction

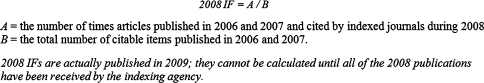

A scientific journal first appeared in 1665; citation of manuscripts began in 1752 [6, 34]. In 1955, the impact factor (IF) was proposed by Eugene Garfield as a simple method to calculate the relative frequencies of citations between journals (Fig. 1) [21]. Subsequently, the IF was used to select journals for the Science Citation Index (SCI), a commercial property of the Institute of Scientific Information (ISI; Philadelphia, PA, USA) and founded by Garfield in 1961 [21]. (ISI subsequently was acquired by Thomson Scientific & Healthcare in 1992, a company that then subsequently became Thomson Reuters.) Beginning in 1975, the IF was incorporated into the newly developed annual Journal Citation Reports (JCR).

Fig. 1.

The IF of a journal equals the ratio of the number of citations in the current year to articles published in the journal in the 2 preceding years divided by the number of citable items published in these 2 years.

Thousands of scientific journals are now listed in the JCR. Although not intended as such and not appropriate for doing so, the IF is widely viewed as a measure of prestige of a journal and indirectly of authors publishing in those journals. Although the IF is probably the most widely used metric to rank journals, such rankings are subject to numerous issues and one can raise some questions regarding the rankings: What are the biases of the IF? Is it easy for editors to manipulate it? Do other citation metrics overcome the potential for misinterpretation? How do these influence journals’ ranking?

There are numerous sources of potential bias in the rankings, some inherent in the system and some not: self-citation (articles from the same journal), citation density (the number of references listed), quality of citations, poor comparability between different specializations, mainly use of English language in publications, type of manuscripts, ease of access, and journals not listed in the SCI database are major disadvantages of the IF [1, 5, 14, 16, 19, 20, 25, 26, 31, 35, 40, 43, 47, 49]. Based on the IF, a citation from an important journal such as Nature is worth no more than a citation from journals in the lowest tiers of publishing [3, 45]. Considering that the SCI database lists only approximately 5000 journals of an estimated total of 126,000 [36, 47, 52], 121,000 journals not listed in the SCI often are referred to as having no IF [35].

Self-citation ranges from 7% to 20% of an article’s references [13, 16, 17, 25, 38]. High self-citation is more common for specialized journals [11, 16, 25, 38, 51] and articles with many authors [13]. Thomson Reuters considers self-citation beyond 20% as suspect of abuse as the journal’s IF is higher and prestige enhanced by self-citation [13, 16, 17, 19, 20, 25, 31]. The potential for abuse and manipulation of the traditional IF highlights the need for and use of self-citation-free metrics for scientific evaluation.

It is not unethical and is even the duty of responsible editors to increase the quality and interest of their journal. It would be unfair to authors and disloyal to publishers if editors did not act in this direction [33]. However, it is easy for editors to manipulate the IF. Editors may artificially increase their journal’s IF by (1) facilitating (or even demanding) self-citation [11, 12, 24, 27, 39, 42, 47, 48, 50, 51], (2) increasing nonsource items with citations, (3) limiting the total number of articles and/or the number of original papers and increasing the number of review and/or technical articles that are more likely to be cited [11, 27, 35, 42, 47, 51], (4) encouraging “salami slicing” [4, 22, 37], and (4) prerelease or timing of publication early during a year thus allowing more time for citation for a given year [19, 28, 49, 51]. Excessive self-citation may cause a large shift in a journal’s IF, particularly if the total rate of citations of that specific journal is low [11, 32, 51]; one journal’s IF increased 18 ranks by one paper containing 303 self-citations [32]. There is clear documentation of editorial feedback to corresponding authors to include self-citations [4, 22, 33, 35, 37]. In addition some editors have used their journal as a personal vehicle for dissemination and promotion of their own work, and placing their articles higher in the publication order [7, 8]. Clearly, this is neither fair nor ethical.

The JCR defines original papers, technical notes, reviews, and proceedings as source items; these items make the denominator of the IF [18, 30, 35]. Nonsource items, including letters, news, abstracts, book reviews, and editorials, are not typically included in the denominator, but if they contain citations, they may be included in the numerator, thus increasing the IF [23, 42, 47, 52]. Increasing the nonsource items, such as by encouraging letters to the editor containing self-citations of the articles being discussed, reference to previous editorials, or running large correspondence sections, is an easy way to increase the IF by increasing self-citation without increasing the source items [11, 27, 33, 35, 42, 47, 51].

Encouraging “salami slicing”, whereby research data and manuscripts are broken into “least publishable units” but more articles, particularly with self-citations, is another method to increase the IF [4, 22, 37].

Considering the 2-year sample period, a paper published in January has 11 months longer to be cited than one published in December of the same year [11]. Moreover, prerelease of article details (soon-to-be-published, ahead of print) increases the immediacy of impact [35].

Self-citation-free Metrics

The SCImago Journal Rank (SJR) indicator measures the prestige transferred to a journal through the citations received from other journals by computing the percentage of citations of the former journal directed to articles of the latter journal during the past 3 years [14, 46]. Major advantages over the IF include the elimination of self-citations in determining the impact or prestige of a journal [14, 46], the quality of citations are based on the prestige of the citing journal [14], a higher number of journals and languages are in its database, and the SJR is freely available without a subscription (JCR requires a subscription) [14, 15, 41, 49]. Major shortcomings of the SJR indicator include the sophisticated calculation methodology and the fact that it divides the prestige gained by a journal to the total number of its articles during the 3-year period being reported [14]. Thus, nonsource items that could be of interest to the readers may be appreciably underestimated with the SJR indicator [14].

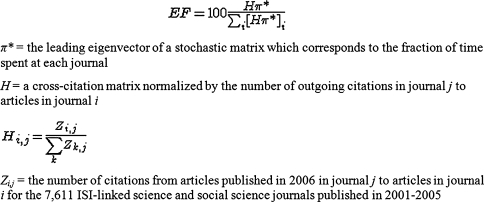

The Eigenfactor™ score measures the number of times that articles published during 1 year cite papers published in the 5 previous years (Fig. 2) [2, 3, 10, 44]. There is a strong correlation between the Eigenfactor™ score and the ‘total cites’ received by a journal [9]. Like the IF, the Eigenfactor™ score is essentially a ratio of the number of citations to the total number of articles [1]. Unlike the IF, it counts citations to journals in the sciences and social sciences, discounts self-citation, and weights each reference according to a stochastic measure of the amount of time researchers spend reading the journal [10, 29]. The Eigenfactor™ score is available only for JCR years 2007 and later [29].

Fig. 2.

The Eigenfactor™ score measures the number of times articles from a journal published during the past 5 years have been cited in the JCR year by direct citation counts from a matrix that records how often each journal cites each other journal. (The formula is published with permission from Eigenfactor.org.)

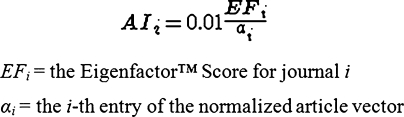

The Article Influence™ score reflects a journal’s prestige based on per article citations (Fig. 3). It is comparable to the IF without self-citation. It is normalized so that the sum total of articles from all journals in the JCR database is 1.00. A score greater than 1.00 indicates that each article in the journal has an above-average influence as the average article in the JCR database, whereas a score less than 1.00 indicates below-average influence [2, 29]. The theory behind the Eigenfactor™ and Article Influence™ scores is that one citation from a high-quality journal has more value than multiple citations from more peripheral publications [1, 2, 10, 29].

Fig. 3.

The Article Influence™ score for each journal is a measure of the per-article citation influence of the journal during a 5-year period. The Article Influence™ score (AIi) equals to the ratio of the journal’s Eigenfactor™ score divided by the fraction of articles published by the journal. (The formula is published with permission from Eigenfactor.org.)

By ranking orthopaedic journals with self-citation-free factors rather than with the IF, substantial changes for journal ranking occur; specialized journals decrease, whereas general journals increase in rank [10, 29, 43, 49]. We examined the first 15 orthopaedic journals in the 2009 JCR IF rank (Table 1) [29]. When we looked at the total cites rank, the ranking of journals changed surprisingly: some journals increased in rank and others decreased in rank (Table 2). Total cites is the total number of times that a journal has been cited by all journals included in the database in the JCR year. However, how many of these are self-citations? In the JCR, self-citations for each journal can be calculated separately. However, the IF without self-citation is not incorporated in the calculation of the journals’ IF [29]. By limiting to the Eigenfactor™ score (Table 3) and the Article Influence™ score (Table 4) that eliminate self-citations, ranking of the journals changed. Considering the calculation methodology for these metrics, this should be attributed to the high total cites and/or low self-citations during a 5-year period for the journals that increased in rank contrary to the journals that decreased in rank [10, 29].

Table 1.

ISI Web of Knowledge ranking based on 2009 JCR Journal Impact Factor (2009 Journal Citation Reports®—Science edition, a Thomson Reuters product)

| Rank | Journal abbreviation | ISSN | Journal impact factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Osteoarthritis Cartilage | 1063-4584 | 3.888 |

| 2 | Am J Sports Med | 0363-5465 | 3.605 |

| 3 | J Bone Joint Surg Am | 0021-9355 | 3.427 |

| 4 | J Orthop Res | 0736-0266 | 3.112 |

| 5 | Spine J | 1529-9430 | 2.902 |

| 6 | J Bone Joint Surg Br | 0301-620X | 2.655 |

| 7 | Spine | 0362-2436 | 2.624 |

| 8 | Arthroscopy | 0749-8063 | 2.608 |

| 9 | Gait Posture | 0966-6362 | 2.576 |

| 10 | J Orthop Sports Phys Ther | 0190-6011 | 2.482 |

| 11 | Injury | 0020-1383 | 2.383 |

| 12 | Phys Ther | 0031-9023 | 2.082 |

| 13 | Clin Orthop Relat Res | 0009-921X | 2.065 |

| 14 | Eur Spine J | 0940-6719 | 1.956 |

| 15 | J Shoulder Elbow Surg | 1058-2746 | 1.934 |

(Data obtained and published with permission from Thomson Reuters.)

Table 2.

ISI Web of Knowledge ranking based on journal total cites (2009 Journal Citation Reports®—Science edition, a Thomson Reuters product)

| Rank | Abbreviated journal title | ISSN | Total cites |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | J Bone Joint Surg Am | 0021-9355 | 31,317 |

| 2 | Spine | 0362-2436 | 30,673 |

| 3 | Clin Orthop Relat Res | 0009-921X | 29,213 |

| 4 | J Bone Joint Surg Br | 0301-620X | 16,267 |

| 5 | Am J Sports Med | 0363-5465 | 13,031 |

| 6 | J Orthop Res | 0736-0266 | 9974 |

| 7 | Arthroscopy | 0749-8063 | 7547 |

| 8 | Osteoarthritis Cartilage | 1063-4584 | 6425 |

| 9 | J Arthroplasty | 0883-5403 | 6147 |

| 10 | Acta Orthop | 1745-3674 | 6086 |

| 11 | J Hand Surg Am | 0363-5023 | 5871 |

| 12 | Injury | 0020-1383 | 5647 |

| 13 | Phys Ther | 0031-9023 | 5568 |

| 14 | J Pediatr Orthop | 0271-6798 | 4612 |

| 15 | Clin Biomech | 0268-0033 | 4537 |

(Data obtained and published with permission from Thomson Reuters.)

Table 3.

ISI Web of Knowledge ranking based on Eigenfactor™ score (2009 Journal Citation Reports®—Science edition, a Thomson Reuters product)

| Rank | Abbreviated journal title | ISSN | Eigenfactor™ score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Spine | 0362-2436 | 0.05135 |

| 2 | Clin Orthop Relat Res | 0009-921X | 0.04063 |

| 3 | Am J Sports Med | 0363-5465 | 0.02739 |

| 4 | J Orthop Res | 0736-0266 | 0.02279 |

| 5 | Osteoarthritis Cartilage | 1063-4584 | 0.02120 |

| 6 | Arthroscopy | 0749-8063 | 0.01802 |

| 7 | J Arthroplasty | 0883-5403 | 0.01597 |

| 8 | Eur Spine J | 0940-6719 | 0.01504 |

| 9 | Injury | 0020-1383 | 0.01380 |

| 10 | Gait Posture | 0966-6362 | 0.01359 |

| 11 | Clin Biomech | 0268-0033 | 0.01200 |

| 12 | Spine J | 1529-9430 | 0.01083 |

| 13 | Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc | 0942-2056 | 0.01034 |

| 14 | Acta Orthop | 1745-3674 | 0.00977 |

| 15 | Phys Ther | 0031-9023 | 0.00929 |

(Data obtained and published with permission from Thomson Reuters.)

Table 4.

ISI Web of Knowledge ranking based on Article Influence™ score (2009 Journal Citation Reports®—Science edition, a Thomson Reuters product)

| Rank | Abbreviated journal title | ISSN | Article Influence™ score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Osteoarthritis Cartilage | 1063-4584 | 1.278 |

| 2 | Am J Sports Med | 0363-5465 | 1.140 |

| 3 | J Orthop Res | 0736-0266 | 1.038 |

| 4 | Gait Posture | 0966-6362 | 0.961 |

| 5 | Clin Orthop Relat Res | 0009-921X | 0.838 |

| 6 | Spine | 0362-2436 | 0.834 |

| 7 | BMC Musculoskelet Disord | 1471-2474 | 0.813 |

| 8 | Phys Ther | 0031-9023 | 0.802 |

| 9 | Clin Biomech | 0268-0033 | 0.765 |

| 10 | Orthop Clin North Am | 0030-5898 | 0.739 |

| 11 | Eur Spine J | 0940-6719 | 0.710 |

| 12 | Arthroscopy | 0749-8063 | 0.687 |

| 13 | J Orthop Trauma | 0890-5339 | 0.617 |

| 14 | Clin J Sport Med | 1050-642X | 0.615 |

| 15 | Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc | 0942-2056 | 0.589 |

(Data obtained and published with permission from Thomson Reuters.)

Readers should understand self-citation may substantially affect a journal’s IF compared with IFs of other journals in the same specialty, self-citation is prone to manipulation and abuse, and the IF does not account for self-citation. Self-citation can bias how a journal is perceived but the bias can be overcome by ranking journals by self-citation-free indices.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Each author certifies that his or her institution has approved the reporting of this case and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

Contributor Information

Andreas F. Mavrogenis, Email: andreasfmavrogenis@yahoo.gr.

Panayiotis J. Papagelopoulos, Email: pjp@hol.gr.

References

- 1.Bergstrom CT. Eigenfactor: measuring the value and prestige of scholarly journals. C&RL News. 2007;68:314–316. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergstrom CT, West JD. Assessing citations with the Eigenfactor metrics. Neurology. 2008;71:1850–1851. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000338904.37585.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergstrom CT, West JD, Wiseman MA. The Eigenfactor metrics. J Neurosci. 2008;28:11433–11434. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0003-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bloch S, Walter G. The Impact Factor: time for change. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2001;35:563–568. doi: 10.1080/0004867010060502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosker BH, Verheyen CC. The international rank order of publications in major clinical orthopaedic journals from 2000 to 2004. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:156–158. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B2.17018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burnham JC. The evolution of editorial peer-review. JAMA. 1990;263:1323–1329. doi: 10.1001/jama.263.10.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis P. Elsevier math editor controversy. Available at: http://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2008/11/25/elsevier-math-editor-controversy/. Accessed April 6, 2010.

- 8.Davis P. Self-publishing editor to retire. Available at: http://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2008/11/28/self-publishing-editor-retires/. Accessed April 6, 2010.

- 9.Davis PM. Eigenfactor: Does the principle of repeated improvement result in better estimates than raw citation counts? J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol. 2008;59:2186–2188. doi: 10.1002/asi.20943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eigenfactor.org. Available at: http://www.eigenfactor.org. Accessed June 21, 2010.

- 11.Epstein D. Impact factor manipulation. The Write Stuff. 2007;16:133–134. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Epstein RJ. Six authors in search of a citation: villains or victims of the Vancouver convention? Br Med J. 1993;306:765–767. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6880.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falagas ME, Kavvadia P. ‘Eigenlob’: self-citation in biomedical journals. FASEB J. 2006;20:1039–1042. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-0603ufm. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Falagas ME, Kouranos VD, Arencibia-Jorge R, Karageorgopoulos DE. Comparison of SCImago journal rank indicator with journal impact factor. FASEB J. 2008;22:2623–2628. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-107938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Falagas ME, Pitsouni EI, Malietzis GA, Pappas G. Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar: strengths and weaknesses. FASEB J. 2008;22:338–342. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9492LSF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fassoulaki A, Paraskeva A, Papilas K, Karabinis G. Self-citations in six anaesthesia journals and their significance in determining the impact factor. Br J Anaesth. 2000;84:266–269. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bja.a013418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gami AS, Montori VM, Wilczynski NL, Haynes RB. Author self-citation in the diabetes literature. CMAJ. 2004;170:1925-1927; discussion 1929-1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Garfield E. Which medical journals have the greatest impact? Ann Intern Med. 1986;105:313–320. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-105-2-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garfield E. How can impact factors be improved? BMJ. 1996;313:411–413. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7054.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garfield E. Dispelling a few common myths about journal impact factors. Scientist. 1997;11:11. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garfield E. Journal impact factor: a brief review. CMAJ. 1999;161:979–980. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gensini GF, Conti AA. [The impact factor: a factor of impact or the impact of a (sole) factor? The limits of a bibliometric indicator as a candidate for an instrument to evaluate scientific production][in Italian]. Ann Ital Med Int. 1999;14:130–133; discussion 134–135. [PubMed]

- 23.Gowrishankar J, Divakar P. Sprucing up one’s impact factor. Nature. 1999;401:321–322. doi: 10.1038/43768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grange RI. National bias in citations in urology journals: parochialism or availability? BJU Int. 1999;84:601–603. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hakkalamani S, Rawal A, Hennessy MS, Parkinson RW. The impact factor of seven orthopaedic journals: factors influencing it. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:159–162. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B2.16983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hansson S. Impact factor as a misleading tool in evaluation of medical journals. Lancet. 1995;346:906. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)92749-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hemmingsson A, Edgren J, Mygind T, Skjennald A. Impact factors in scientific journals. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;15:619. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hemmingsson A, Mygind T, Skjennald A, Edgren J. Manipulation of impact factors by editors of scientific journals. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:767. doi: 10.2214/ajr.178.3.1780767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.ISI Web of Knowledge. Available at: http://adminapps.isiknowledge.com/JCR/help/h_eigenfact.html. Accessed June 21, 2010.

- 30.Jacso P. A deficiency in the algorithm for calculating the impact factor of scholarly journals: the Journal Impact Factor. Cortex. 2001;37:590–594. doi: 10.1016/S0010-9452(08)70602-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones AW. Impact factors of forensic science and toxicology journals: what do the numbers really mean? Forensic Sci Int. 2003;133:1–8. doi: 10.1016/S0379-0738(03)00042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kirchhof B, Bornfeld N, Grehn F. The delicate topic of the impact factor. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2007;245:925–927. doi: 10.1007/s00417-007-0618-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krell FT. Should editors influence journal impact factors? Learned Publishing. 2010;23:59-62. (Available at: http://www.dmns.org/science/curators/frank-krell/editors-influence.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2010.).

- 34.Kronick DA. Peer-review in 18th century scientific journalism. JAMA. 1990;263:1321–1322. doi: 10.1001/jama.263.10.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kurmis AP. Understanding the limitations of the journal impact factor. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:2449–2454. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200312000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lankhorst GJ, Franchignoni F. The ‘impact factor’: an explanation and its application to rehabilitation journals. Clin Rehabil. 2001;15:115–118. doi: 10.1191/026921501676657944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Linde A. On the pitfalls of journal ranking by Impact Factor. Eur J Oral Sci. 1998;106:525–526. doi: 10.1046/j.0909-8836..t01-1-.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miguel A, Martí-Bonmatí L. Self-citation: comparison between Radiología, European Radiology and Radiology for 1997–1998. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:248–252. doi: 10.1007/s003300100894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller JB. Impact factors and publishing research. Scientist. 2002;16:11. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Motamed M, Mehta D, Basavaraj S, Fuad F. Self citations and impact factors in otolaryngology journals. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2002;27:318–320. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.2002.00574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mueller PS, Murali NS, Cha SS, Erwin PF, Ghosh AK. The association between impact factors and language of general internal medicine journals. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006;136:441–443. doi: 10.4414/smw.2006.11496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neuberger J, Counsell C. Impact factors: uses and abuses. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:209–211. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200203000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Postma E. Inflated impact factors?. The true impact of evolutionary papers in non-evolutionary journals. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e999. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Price DJ. Networks of scientific papers. Science. 1965;149:510–515. doi: 10.1126/science.149.3683.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rossner M, Epps H, Hill E. Show me the data. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:1091–1092. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200711140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.SCImago Research Group. Description of SCImago Journal Rank Indicator. Available at: http://www.scimagojr.com/SCImagoJournalRank.pdf. Accessed January 20, 2008.

- 47.Seglen PO. Why the impact factor of journals should not be used for evaluating research. BMJ. 1997;314:498–502. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7079.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sevinc A. Manipulating impact factor: an unethical issue or an Editor’s choice? Swiss Med Wkly. 2004;134:410. doi: 10.4414/smw.2004.10761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Siebelt M, Siebelt T, Pilot P, Bloem RM, Bhandari M, Poolman RW. Citation analysis of orthopaedic literature; 18 major orthopaedic journals compared for Impact Factor and SCImago. BMC Musculoskeletal Disord. 2010;11:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith R.Journal accused of manipulating impact factor Br Med J 19973144619056791 [Google Scholar]

- 51.The PLoS Medicine Editors. The impact factor game: it is time to find a better way to assess the scientific literature. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Whitehouse GH. Impact factors: facts and myths. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:715–717. doi: 10.1007/s00330-001-1212-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]