While the accreditation of higher education institutions and their programs is voluntary in the United States, students' opportunities are hindered substantially if they attend or earn degrees from nonaccredited programs. For example, federal financial aid is available only to those students enrolled in institutions that have been accredited by an agency recognized by the US Department of Education. In the health professions, graduation from an accredited program is generally a prerequisite for sitting for state board examinations required for licensure as a practitioner.

Accreditation is an important external certification that a program provides an educational experience that is consistent with producing graduates prepared to enter the workforce with the expected knowledge and abilities of entry-level practitioners. Recognizing that practice environments vary substantially, an accreditation agency must ensure that the educational programs it accredits are based on current and emerging standards of practice. Accrediting agencies must, however, strike a balance between ensuring minimal competencies of a program's graduates and allowing sufficient programmatic flexibility to support educational experimentation and innovation.

Reaccreditation of educational programs can be a healthy process that provides an opportunity for programs to assess carefully and strategically their progress, opportunities, and challenges. It is also a time- and resource-intensive process; programs commonly devote 12 to 18 months to the development of a self-study and programmatic assessment in light of Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) standards. During this period, widespread engagement in the self-study by faculty members, students, and staff members is necessary. The time and resources devoted to this process often delay the implementation of other important initiatives; thus, the frequency of reaccreditation itself can slow or minimize the ability of a program to implement educational advances. There is a need for a healthy tension between a frequency of reaccreditation that ensures that the quality of programs does not decline and a frequency that does not affect programmatic advancement adversely.

As deans of pharmacy programs at institutions affiliated with the Committee on Institutional Cooperation (CIC, encompassing the Big Ten institutions and the University of Chicago), the authors collectively represent some of the longest established pharmacy programs in the nation, each with a program history dating between 120 and 150 years. Each of our programs has achieved continuous accreditation since the inception of accreditation of pharmacy programs and has a long history of leadership in educational innovation and advances in the profession of pharmacy. In our annual meetings as a group of deans, we have devoted significant time to discussing the accreditation process for doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) programs. Each of us has experienced the forestalling of important initiatives within our colleges/schools during a period of self-study for reaccreditation. Our shared experiences have convinced us that it is time to reconsider the period for which PharmD programs are accredited.

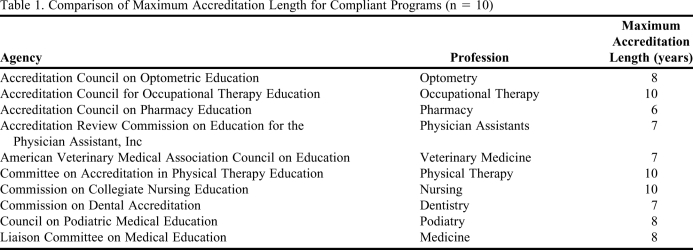

It is informative to compare the accreditation cycles for PharmD programs with those for other health professions. Table 1 provides a comparison of the maximum length of accreditation for compliant programs for 10 different health professions, all but 2 of which (nurses and physician assistants) require a doctorate-level first professional degree. As shown by this data, ACPE provides the shortest maximum accreditation period of any agency accrediting a health professions program.

Table 1.

Comparison of Maximum Accreditation Length for Compliant Programs (n = 10)

Are there rational reasons for a shorter accreditation period for PharmD programs compared to other professions? One reasonably could not argue that the complexity of practice in pharmacy exceeds that of other professions, such as medicine and optometry. It would also be indefensible to assert that the pace of change within pharmacy exceeds that of other health professions. In short, we see no reasonable justification for the period of accreditation for established PharmD programs being shorter than that of any other health professions program.

We suggest that the current ACPE policy of awarding well-established programs the same maximal period of accreditation awarded to new programs be modified. Programs with a long history of continuous accreditation are granted the same accreditation length as programs that have gone through only 1 accreditation cycle. We recommend implementation of a tiered system in which programs with a significant history of successful accreditation be granted longer periods between reaccreditation.

What are the risks associated with lengthening the period of accreditation for well-established PharmD programs? The obvious risk is that a program could become non-compliant with accreditation standards between review periods. No evidence exists, however, that shows programmatic compliance is impacted by length of time between review periods. Other health professional programs are managed acceptably with longer periods of time between accreditation visits. In addition, the ACPE's notification requirement in the event of a substantive change in the program or its associated resources provides a process for the council to trigger an earlier programmatic review if concerns about continued compliance with the standards arise as a result of meaningful changes. Recognizing the resources (time, energy, and dollars) required to conduct a self-study and reaccreditation site visit, the benefits for institutions of an extended period of accreditation should be obvious. In addition, it would reduce the burden on ACPE, which has been recognizably stretched with the substantial growth of new programs. An extension of the accreditation length for established programs would allow the council to focus more carefully on at-risk or noncompliant programs.

All programs operate in an increasingly resource-constrained environment. This includes reduced budgets and increased demands on faculty time and energy. Balancing the competing demands on human and fiscal capital is imperative to sustain forward momentum within the profession. The time has come to reassess the time span between reaccreditation as a component of this balancing process. The authors advocate for an extension in the period of maximal accreditation for well-established pharmacy programs (perhaps defined as 3 or more continuous full-accreditation cycles). We believe that such an extension, perhaps combined with an approval process for specific proposed mid-cycle innovations in a program, will allow programs to redirect the resources required for routine reaccreditation into educational innovations, and thus accelerate the pace of change in pharmacy education.