Abstract

Context

In a natural experiment in which some families received income supplements, adolescent behavioral symptoms fell significantly. These adolescents are now young adults.

Objective

To examine the effects of income supplements in adolescence and adulthood on the prevalence of adult psychiatric disorders.

Design

Quasi-experimental, longitudinal.

Population and setting

A representative sample of 1420 children ages 9, 11, or 13 in 1993 (25%, n=349, American-Indian) were assessed for psychiatric and substance use disorders (SUD) through age 21 (1993–2006). From 1996, when a casino opened on the Indian reservation, every American-Indian but no Non-Indians received an annual income supplement that increased from $500 to around $9000.

Main outcome measures

Rates of adult psychiatric disorders and SUD based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders1 in 3 age cohorts, adjusted for age, sex, length of time in the family home, and number of Indian parents.

Results

As adults, significantly fewer Indians than non-Indians had a psychiatric disorder (Indians, 30.2%, non-Indians, 36.0%, Odds Ratio (OR) 0.46, 95% Confidence Interval (CI) 0.30, 0.72, p=.001), particularly alcohol and cannabisabuse and/or dependence. The youngest age-cohort of Indian youth had the longest exposure to the family income. Interactions between race/ethnicity and age-cohort were significant. Planned comparisons showed that fewer of the youngest Indian age-cohort had any psychiatric disorder (31.4%) than the Indian middle cohort (41.7%, OR 0.43, 95% CI 0.24, 0.78, p=.005) or oldest cohort (41.4%, OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.51, 0.94, p=.012) or the youngest non-Indian cohort (37.1%, 0.66, 95% CI 0.48, 0.90 p=.008). Study hypotheses were not upheld for nicotine or other drugs, or emotional or behavioral disorders. The income supplement received in adulthood had no impact on adult psychopathology.

Conclusions

Lower rates of psychopathology in American-Indian youth following a family income supplement, compared with the non-exposed, non-Indian population, persisted into adulthood.

In 2003 we published the results of a natural experiment in which an income supplement given to all members of one community, and to none in another, predicted significantly fewer adolescent psychiatric symptoms in the “treated” group.2 At the time of the earlier study the participants were adolescents living at home. They are now adults and in receipt of their own income supplement. This paper addresses the question of whether the effect of the family income supplement persist into adulthood, controlling for past and current risk and protective factors, including poverty.

METHODS

Setting and Population

The Great Smoky Mountains Study is a longitudinal study of the development of psychiatric and substance use disorders (SUD) in rural and urban youth. 3, 4 In 1993, a representative sample of 1,420 children aged 9, 11, and 13 at intake was recruited from some 12,000 children of these ages living in 11 counties in western North Carolina, using a household equal probability, accelerated cohort design.5

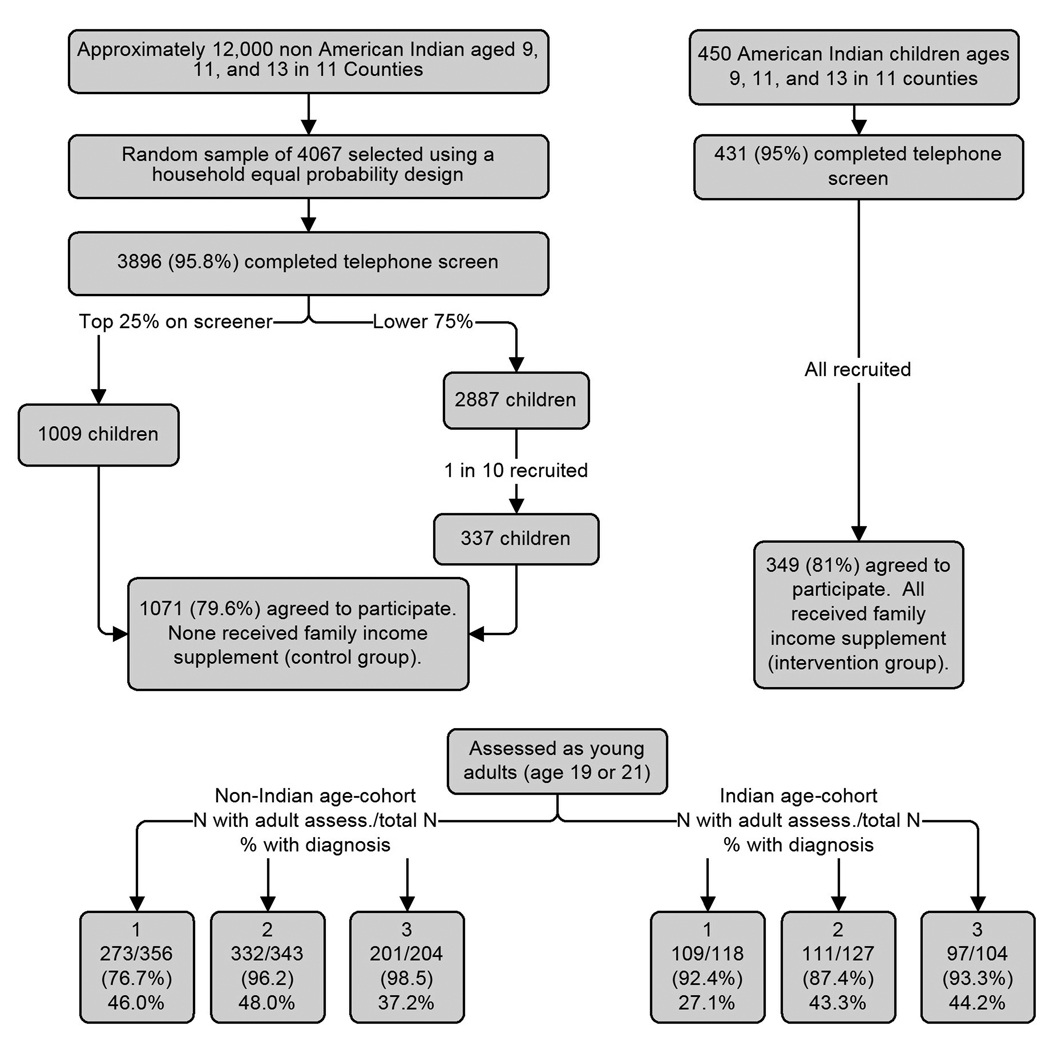

American-Indian children were oversampled. Potential subjects were children of parents enrolled as members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, who have a federal reservation in the study area. All age-appropriate Indian children were recruited. The final sample (Figure 1) consisted of 349 Indian children (81.0% of those invited) and 1,071 non-Indian children (79.6% of those invited); 92.5% (n=991) of the latter were White and 7.5% (n=80) African-American (the latter were not used in these analyses). Individuals’ contributions were weighted proportionately to their probability of selection into the study, so that the results are representative of the underlying population. In the text N=actual numbers, and percentages are weighted.

Figure 1. Participant flowchart.

Response rates did not differ by age, race, cohort, poverty, or psychiatric status.

By age 21, the mean number of assessments was 7, with an average response rate of 83%. Attrition and non-response did not differ across age-cohorts and were not associated with psychiatric status.

The natural experiment consisted of an income supplement given to every member of the Eastern Band of Cherokees when a casino was opened on their reservation in 1996. Every tribal member receives a percentage of the casino’s profits, paid every 6 months. Children's earnings are paid into a bank account held for them until age 18. By 2006 the payment was around $9,000 a year. The opening of the casino also increased the number of jobs available in the casino, where Indians receive hiring preference, or in surrounding motels and restaurants, where they do not. Non-Indian youth in the surrounding counties received no comparable income supplement.

Procedures

Participants were interviewed, usually at home, once a year from 1993 through 1996, then at ages 13, 14, 15, 16, 19, and 21. The participant and a parent (usually the mother) were interviewed until the participant was 16, after which only participants were interviewed. Assessments took place on a date as close a possible to the participant’s birthday. All interviewers were residents of the study area; some were American-Indian. They received one month of training and constant quality control by supervisors and study faculty. Participants up to age 16 signed assent forms, and parents (until participants reached 16) and older participants signed informed consent forms. The study and consent forms were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Duke University and the Tribal Council of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.

Measures

Outcome Variables

The outcomes were any DSM-IV psychiatric disorder, any behavioral disorder (conduct, oppositional, or antisocial personality disorder), any emotional disorder (depressive or anxiety disorders) and any substance use disorder (SUD) in early adulthood; i.e., at either or both age 19 and 21 assessments (1999–2006). SUD included abuse of or dependence on alcohol, cannabis, nicotine (dependence only), and “other drugs”: cocaine, amphetamines, inhalants, opioids, hallucinogens, and sedatives. Psychiatric and drug status were assessed using the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA) at ages 9–16 and the Young Adult Psychiatric Assessment (YAPA) in adulthood.6–8 These are structured interviews that enable interviewers to determine whether symptoms, defined in an extensive glossary, are clinically significant, and to code their frequency, duration, severity, and onset. The CAPA/YAPA scoring algorithms generate either symptom scales or diagnoses made using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association, fourth edition (DSM-IV),1 The time frame of the CAPA/YAPA is the three months preceding each interview.

Classification Variables

Enrollment in the Eastern Band of Cherokee provided access to the income supplement.

Other variables included in the analyses

As well as age at assessment, gender, race/ethnicity of interviewer, current household income, family history of poverty, and adolescent psychiatric symptoms, the following variables were included in the analyses:

Length of exposure to family income supplement

As shown in Table 1, the 3 age-cohorts in the study were likely to spend different amounts of time living in the family household after the income supplement began and before the participants became independent. At the time of the last adolescent data collection point, at age 16, when all participants were living at home, the youngest had already had 4 years of family income supplement, the middle cohort 2, and the oldest cohort less than a year. Therefore, age-cohort was used in the analyses as a measure of length of exposure to the income supplement in the family setting.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Great Smoky Mountains Study age cohorts through age 21

| Youngest Cohort (12 in 1996) N=474 |

Middle Cohort (14 in 1996) N=470 |

Oldest cohort (16 in 1996) N=388 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indian | Non-Indian | Indian | Non-Indian | Indian | Non-Indian | |

| Number of participants | 118 | 356 | 127 | 343 | 104 | 284 |

| Number of observations | 873 | 2357 | 868 | 2283 | 529 | 1398 |

| Percent female | 47 | 46 | 45 | 41 | 48 | 46 |

| Age at beginning of study (1993) | 9 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 13 | 13 |

| Age at opening of casino (1996) | 12 | 12 | 14 | 14 | 16 | 16 |

| N. years of family income supplement at age 16 assessment | 4 | 2 | 0 | |||

| Amount received at age 18 | 35,000 | 0 | 19,000 | 0 | 6,000 | 0 |

| % not currently living in family home by age 21 | 80.70% N=88 | 55.58% N=167 | 82.0% N=91 | 48.37% N=149 | 80.40% N=78 | 52.38% N=123 |

| Any adult psychiatric disorder | 31.36% N=37 | 37.08% N=122 | 41.73% N=53 | 42.52% N=148 | 41.35% N=43 | 30.59% N=94 |

| Any adult substance abuse or dependence | 22.88% N=27 | 36.02% N=121 | 33.86% N=43 | 37.54% N=130 | 34.62% N=36 | 28.89% N=89 |

| Any adult alcohol abuse or dependence | 14.41% N=17 | 24.29% N=72 | 22.05% N=28 | 24.45% N=86 | 27.88% N=29 | 20.40% N=62 |

| Any adult cannabis abuse or dependence | 10.17% N=12 | 16.43% N=61 | 24.42% N=31 | 17.42% N=55 | 24.04% N=25 | 14.84% N=35 |

| Any adult “hard” drug abuse or dependence | 0.85% N=1 | 3.88% N=15 | 3.96% N=8 | 0.88% N=9 | 3.85% N=4 | 4.19% N=13 |

| Any nicotine dependence | 16.95% N=20 | 14.10% N=51 | 22.05% N=28 | 16.18% N=59 | 13.48% N=14 | 13.34% N=45 |

| Any adult behavioral disorder | 0.49% N=1 | 1.35% N=5 | 1.98% N=4 | 2.76% N=12 | 5.23% N=9 | 0.92% N=5 |

| Any adult emotional disorder | 5.34% N=11 | 13.05% N=71 | 5.94% N=12 | 6.33% N=38 | 6.40% N=11 | 9.61% N=33 |

N= number of live participants. %=percentage weighted to represent population

Number of adults receiving income supplements

The amount of money per household from the supplement varied with the number of adult recipients in the home. For these analyses we made the assumption that the adults in the household whose access to additional resources would have the most effect on the participant would be resident parents while the subject lived in the family home, and self and spouse thereafter. Thus, there could be 0, 1, or 2 supplements counted per study participant while living at home, and 1 or 2 when living independently after age 18.

Banked childhood income

At age 18, American-Indian participants received their own income supplement, together with the accumulated sum that had been held in trust for them (Table 1).

Living independently

Indian youth who continued to live at home may have been exposed to more of the effects of the family income supplement. Whether the participant was living at home or independently was included as a covariate.

Potential mediators

Data were collected on 126 risk factors (see http://psych.duhs.duke.edu/library/pdf/RiskfactorsCodebook.pdf). A mediational model9 requires that the significant effect of the intervention on later psychopathology should become non-significant once the putative mediator is entered into the model. To qualify as potential mediators, risk factors must follow the onset of the intervention, and show a significant bivariate association with the outcome variable.9 We also required them to occur in more than 5% of the participants.

Analyses

We applied a marginal model approach (Generalized Estimating Equations, GEE), to the analysis of these longitudinal data. GEE is a method developed for dealing with complex longitudinal, repeated, or clustered data, where the observations within each cluster are correlated.10 SAS PROC GENMOD11 was used to generate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for main effects and planned contrasts. All p-values refer to 2-tailed tests. Missing data were imputed using a logistic regression approach (the LOGISTIC option on the MONOTONE statement in SAS PROC MI). Outcome variables were predicted by age and the sampling weight which incorporates information about race, sex, cohort, and pre-study screen status. Five complete datasets were produced using a Bernoulli draw to model the uncertainty of imputed values. SAS PROC MIANALYZE was used to read parameter estimates and associated covariance matrices for each imputed dataset and to derive valid statistical inferences and estimates.

To test the hypothesis that, among the Indian youth, the effects of the income supplement would be strongest for youngest children, we compared the youngest cohort with the two older ones. Age-cohort was used rather than age because the ages were clustered. We also tested the prediction that the youngest Indian cohort would have lower rates of disorder than the age-matched non-Indian cohort, who had no intervention,

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the prevalence of adult disorders by age 21, in the 3 age-cohorts of Indian and Non-Indians. Table 2 presents the results of testing whether there were significant differences in the prevalence rates of adult psychiatric and substance use disorders shown in Table 1 by race, age-cohort, or their interaction, controlling for the covariates listed above.

Table 2.

Results of logistic models of effects of race, age-cohort, and race-by-age-cohort interaction, on rates of adult psychiatric and substance use disorders, controlling for age at assessment, gender, race/ethnicity of interviewer, current household income, family history of poverty, and adolescent psychiatric symptoms

| Race | Age-cohort | Race by age-cohort | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio |

95% CI | p | Odds Ratio |

95% CI | p | Odds Ratio |

95% CI | p | |

| Any diagnosis | 0.46 | 0.30, 0.72 | .001 | 0.77 | 0.58, 1.01 | .059 | 1.30 | 1.07, 1.60 | .009 |

| Any substance use disorder | 0.58 | 0.32, 0.90 | .014 | 0.80 | 0.61, 1.05 | .109 | 1.25 | 1.03, 1.53 | .027 |

| Alcohol abuse/dependence | 0.49 | 0.29, 0.79 | .004 | 0.86 | 0.64, 1.16 | .337 | 1.33 | 1.06, 1.67 | .012 |

| Cannabis abuse/dependence | 0.58 | 0.35, 0.96 | .036 | 0.89 | 0.64, 1.24 | .506 | 1.32 | 1.04,.1.67 | .019 |

| Nicotine dependence | 1.05 | 0.65, 1.71 | .829 | 0.92 | 0.67, 1.28 | .643 | 0.99 | 0.79, 1.25 | .985 |

| Other drug abuse/dependence3 | 0.79 | 0.25, 2.45 | .691 | 0.99 | 0.43,.2.26 | 0.985 | 1.14 | 0.68, 1.92 | .599 |

| Any emotional disorder1 | 0.52 | 0.24, 1.10 | .089 | 0.70 | 0.44, 1.12 | .143 | 1.14 | 0.80, 1.65 | .452 |

| Any behavioral disorder2 | 0.56 | 0.14, 2.22 | .410 | 1.38 | 0.71, 2.69 | .344 | 1.40 | 0.80, 2.43 | .410 |

Any DSM-IV anxiety or depression diagnosis.

Any DSM-IV conduct, oppositional or antisocial personality disorder.

Any abuse of or dependence on cocaine, amphetamines, inhalants, opioids, hallucinogens, or sedatives.

The main effect of race was significant for any adult psychiatric disorder (non-Indian, 36.0%, Indian, 30.2%, OR 0.54, 95% CI 0.36, 0.80, p=.003). This was true of any SUD (non-Indian, 30.6%, Indian, 28.6%, OR 0.59, 95% CI 0.39, 0.90, p=.014), and any alcohol abuse or dependence (non-Indian 23.8%, Indian 20.3%, OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.32, 0.83, p=.006) or cannabis abuse or dependence (non-Indin 19.5%, Indian 16.7%, OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.38, 0.99, p=.049). Main effects of age-cohort were not significant. There was a significant interaction between age-cohort and race for any adult psychiatric disorder (OR 1.30, 95% CI 1.07, 1.60, p=.009), SUD (OR 1.25, 95% CI 1.03, 1.53, p=.027), and any alcohol abuse or dependence (OR 1.33, 95% CI 1.06, 1.67, p=.012) or cannabis abuse or dependence (OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.04, 1.67, p=.019). The study hypotheses were not upheld for nicotine dependence, other drug abuse or dependence, or emotional or behavioral disorders. Planned comparisons among the 3 age-cohorts (Table 3) showed that the youngest Indian age-cohort was significantly less likely to have any adult psychiatric disorder than either the middle (OR 0.43, 95% CI 0.24, 0.78, p=.005) or oldest (OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.51, 0.94, p=.012) Indian age-cohort, between whom there were no differences. The youngest Indians also had fewer disorders than the youngest non-Indians (OR 0.66, 95% CI 0.48, 0.90, p=.008).

Table 3.

Planned contrasts: Youngest cohort of Indians vs: 1.Oldest cohort of Indians; 2: Middle cohort of Indians; 3: Youngest cohort of non-Indians, controlling for age at assessment, gender, race/ethnicity of interviewer, current household income, family history of poverty, and adolescent psychiatric symptoms.

| Youngest cohort of Indians versus: | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Middle cohort of Indians | 2. Oldest cohort of Indians | 3. Youngest cohort of non- Indians |

|||||||

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | |

| Any diagnosis | 0.43 | 0.24, 0.78 | .005 | 0.69 | 0.51, 0.94 | .012 | 0.66 | 0.48, 0.90 | .008 |

| Any substance use disorder | 0.53 | 0.31, 0.90 | .020 | 0.77 | 0.58, 1.03 | .080 | 0.71 | 0.53, 0.96 | .024 |

| Alcohol abuse/dependence | 0.44 | 0.22, 0.89 | .022 | 0.60 | 0.42, 0.88 | .005 | 0.58 | 0.40, 0.85 | .005 |

| Cannabis abuse/dependence | 0.28 | 0.12, 0.60 | .001 | 0.62 | 0.42, 0.91 | .016 | 0.73 | 0.46, 1.17 | .491 |

We next examined mediators of the effect of adolescent exposure to the family income supplement on adult SUD. Of the risk factors assessed in the study, 28 occurred after the intervention onset and at greater than 5% prevalence, but only 4 of these were associated with adult SUD in bivariate analyses (see eTable 1). Only one met full criteria as a mediator of the intervention: association with delinquent friends in adulthood. The youngest Indians were significantly less likely than older Indians to report delinquent friends in adulthood (9.2% (n=9) vs 22.7% (n=41), β−1.06, SE .345, p=.002). The impact of the intervention (β −.874, SE .311, p=.005) fell to a nonsignificant level (β −.604, SE .321, p=.060) when the model controlled for delinquent adult friends. Similar results were seen when the youngest Indians were compared with the youngest Non-Indians. Family supervision, which had mediated the effect of the income supplement in adolescence,2 did not extend its influence into adulthood. Material hardship in adolescence was associated with adult SUD, but did not mediate the intervention effect.

COMMENT

In this paper we examine the long-term effects on adult psychiatric and substance use disorders of a quasi-experimental family income intervention that began in adolescence. Exposure to increased income in an American Indian population, compared with an unexposed non-Indian population, was associated with fewer psychiatric disorders in adulthood. The effect was strongest for alcohol and cannabis abuse and/or dependence, and was specific to the youngest cohort.

Despite decades of research describing the harmful effects of family poverty on children’s emotional and behavioral development, e.g., 12, 13–17 experimental or quasi-experimental manipulations of family income that could go beyond description are rare,18 and tend to examine the impact of such manipulations on physical health or academic attainment, rather than emotional or behavioral functioning.19, 20 Other analyses of the Great Smoky Mountains data set have focused on educational and criminal outcomes.21 The few studies looking at emotional and/or behavioral outcomes tend to have a short time frame e.g., 22, 23 Some studies of school-based interventions have followed children through to adulthood (e.g., 24, 25), but we have found none that have looked at the long-term effects of family income supplementation on adult psychological functioning.

In these analyses an income supplement provided to all American-Indian families since the mid-1990s was associated with fewer psychiatric diagnoses not only in adolescence, while the study participants were living at home, but also in young adulthood, when the majority had moved out of the family home, and when the participants were receiving their own income supplement. The effect was seen only in the youngest age cohort, who were 12 when the income supplement began, and who therefore were exposed to it for several years before leaving home. The personal income supplement received from age 18 onward was not associated with less psychopathology.

Substance use disorders emerged in middle adolescence and increased in frequency through the middle twenties, becoming by far the most common psychiatric problems reported by the study participants.26, 27 We have already shown that early conduct problems predicted the onset of adolescent SUD in this sample,28, 29 and it is not surprising that this is the aspect of behavioral problems that showed the intervention effect in young adulthood. The youngest Indian cohort also achieved higher levels of education as adults and fewer minor criminal offenses than the rest.21 This profile of deviance reduction is consistent with other literature, 22, 23 with the addition of a longer time-frame and a quasi-experimental design. The present study, like the previous one, shows little effect of the intervention on anxiety and depression.

The most important aspect of this follow-up into adulthood is to demonstrate that an intervention occurring in adolescence can predict outcomes in adulthood. The fact that the effects were seen principally in the youngest age-cohort could be explained by age at exposure or length of exposure.30, and the design of the intervention does not enable us to decide between these possible explanations. The policy conclusion Is, however, the same: the income supplement was only effective if it began early, as studies of other outcomes have shown.19, 20

In adolescence, the income supplement reduced behavioral symptoms, and the effect was mediated by increased parental supervision. In adulthood, fewer delinquent friends mediated the relationship between the family supplement and adult SUD. Possibly, the increased supervision in adolescence, while no longer exerting a direct influence on adult psychopathology, helped keep young adults away from delinquent friends and thence exposure to drugs as adults.

The income supplement available to the Indian families was quite considerable: about $9,000 a year by 2006. Income support for poor families at this level would be an enormous investment of public resources. However, the costs of social control of delinquent behaviors, including drug problems, are also very high.31–34 This quasi-experimental study is, perhaps, more important in linking a developmentally-specific environmental intervention with an adult outcome showing strong genetic liability.35, 36

The Great Smoky Mountains study has several advantages for examining the long-term impact of an income intervention on psychiatric disorder. First, the intervention applied equally, and in equal amounts, to everyone in the “treatment” group, and to no-one in the other group. Thus, the key variable, the family income supplement, was not bestowed because of family characteristics that could influence psychiatric outcomes (as is the case with most forms of income supplementation).19, 20, 37–39 Second, since the groups were originally selected randomly from the population (non-Indians) or consisted of the whole population of the same age (American-Indians), selection biases were minimized. Third, the study used a within-subjects, prospective design, with everyone assessed on several occasions before and after the casino opened, and again as young adults. Fourth, the three age cohorts enabled us to examine the impact of length of exposure to the intervention on outcomes. Fifth, a wide range of data was available to test for mediators.

The study also has important limitations. The samples were not large and included only two race/ethnic groups large enough for statistical comparisons: Cherokee Indians and non-Hispanic whites. Race/ethnicity was entirely confounded with the intervention, as was age with length of the intervention. The amount saved during childhood that the Indian participants received at age 18 was also confounded with age cohort, and so its effects could not be estimated separately. However, the fact that all the cohorts had very similar incomes at age 19 and 21 suggests that the lump sum was not used to buy different levels of long-term benefits (such as education leading to a better job40). We were not able to test the hypothesis that the effect on SUD was the indirect result of community benefits of the casino, such as greater opportunity for parental employment,41 or of community-wide risks such as increased gambling addiction because of the proximity of the casino, although there is no reason to expect cohort differences in such community-wide effects. The study took place in a mixed urban-rural area of the United States, and a family income intervention like this one might not have a similar effect in an inner-city area. Finally, although we observed a long-term effect of a family income supplement, we lack the information to understand how and why it worked as it did.

The fact that the intervention was effective in youth with and without a family history of drug problems is not an argument that behavioral and substance abuse disorders are not “brain disorders” and so are outside the remit of psychiatrists in their new manifestation as clinical neuroscientists.42 Rather, it suggests that whether or not individuals have a genetic vulnerability to a disorder, there are environmental interventions that can have long term benefits, even after the intervention is over.

Acknowledgement

Dr. Costello, as primary investigator, had full access to all of the data in this study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data, and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Costello, Angold

Acquisition of data: Costello, Angold

Analysis and interpretation of data: Costello, Angold, Erkanli, Copeland

Drafting of manuscript: Costello, Angold, Copeland

Critical revision of manuscript for important intellectual content: Costello, Angold, Erkanli, Copeland

Statistical expertise: Erkanli, Copeland

Obtained funding: Costello, Angold

Administrative, technical, or material support: Costello, Angold, Erkanli

Study supervision: Costello

The work presented here was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (MH63970, MH63671, and MH48085), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA11301), and NARSAD.

These institutions provided financial support for every aspect of the study.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interest relevant to the subject of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

E. Jane Costello, Email: jcostello@psych.duhs.duke.edu.

Alaattin Erkanli, Email: aerkanli@psych.duhs.duke.edu.

William Copeland, Email: william.copeland@duke.edu.

Adrian Angold, Email: adrian.angold@duke.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costello EJ, Compton SN, Keeler G, Angold A. Relationships between poverty and psychopathology: A natural experiment. JAMA. 2003;290:2023–2029. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.15.2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burns BJ, Costello EJ, Angold A, et al. Children's mental health service use across service sectors. Health Affairs. 1995;14:147–159. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.14.3.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costello EJ, Angold A, Burns BJ, et al. The Great Smoky Mountains Study of Youth: Goals, designs, methods, and the prevalence of DSM-III-R disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53:1129–1136. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830120067012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schaie KW. A general model for the study of developmental problems. Psychological Bulletin. 1965;64:92–107. doi: 10.1037/h0022371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Angold A, Costello EJ. A test-retest reliability study of child-reported psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses using the Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA-C) Psychological Medicine. 1995;25:755–762. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700034991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Angold A, Prendergast M, Cox A, Harrington R, Simonoff E, Rutter M. The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA) Psychological Medicine. 1995;25:739–753. doi: 10.1017/s003329170003498x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angold A, Costello EJ. The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Assessment (CAPA) Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:39–48. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diggle PJ, Liang KY, Zeger SL. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.SAS/STAT® Software: Version 9 [computer program]. Version. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elder GH., Jr . Children of the Great Depression: Social Change in Life Experience (25th anniversary edition) Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conger R, Conger K, Matthews L, Elder G. Pathways of economic influence on adolescent adjustment. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27:519–541. doi: 10.1023/A:1022133228206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gershoff ET, Aber JL, Raver CC, Lennon MC. Income is not enough: incorporating material hardship into models of income associations with parenting and child development. Child Development. 2007 Jan–Feb;78(1):70–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00986.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duncan GJ, Rodgers WL. Longitudinal aspects of childhood poverty. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1988;50:1007–1021. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McLeod JD, Shanahan MJ. Trajectories of poverty and children's mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1996;37:207–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foster H, Nagin D, Hagan J, Angold A, Costello E. Specifying criminogenic strains: stress dynamics and conduct disorder trajectories. Development and Behavior. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rutter M. Poverty and child mental health: Natural experiments and social causation. JAMA. 2003;290:2063–2064. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.15.2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elesh D, Lefcowitz MJ. The effects of the New Jersy-Pennsylvania Negative Income Tax Experiment on health and health care utilization. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1977;18:391–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spiegelman RG, Yaeger KE. The Seattle and Denver income-maintenance experiments: Overview. Journal of Human Resources. 1980;15:463. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akee R, Costello E, Copeland W, Keeler G, Angold A. Parent’s Incomes and Children’s Outcomes: A Quasi-Experiment with Casinos on American Indian Reservations. American Economic Journal. 2010;2:86–115. doi: 10.1257/app.2.1.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berger LM, Paxson C, Waldfogel J. Income and child development. Children and Youth Services Review. 2009;31(9):978–989. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Epps SR, Huston AC. Effects of a poverty intervention policy demonstration on parenting and child behavior: a test of the direction of effects. Social Science Quarterly. 2007;88(2):344–365. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schweinhart LJ, Weikart DP. The high/scope preschool curriculum comparison study through age 23. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 1997;12:117–143. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kellam SG, Brown CH, Poduska JM, et al. Effects of a universal classroom behavior management program in first and second grades on young adult behavioral, psychiatric, and social outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;95 Supplement 1:S5–S28. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perkonigg A, Pfister H, Hofler M, et al. Substance use and substance use disorders in a community sample of adolescents and young adults: incidence, age effects and patterns of use. European Addiction Research. 2006;12(4):187–196. doi: 10.1159/000094421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von Sydow K, Lieb R, Pfister H, Hofler M, Sonntag H, Wittchen HU. The natural course of cannabis use, abuse and dependence over four years: a longitudinal community study of adolescents and young adults. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. 2001;64(3):347–361. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sung M, Erkanli A, Angold A, Costello E. Effects of age at first substance use and psychiatric comorbidity on the development of substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;75:287–299. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sung M, Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Angold A. Puberty and the onset of alcohol and drug use: A longitudinal community study. Drug & Alcohol Dependence. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rutter M. Age as an ambiguous variable in developmental research: Some epidemiological considerations from developmental psychopathology. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1989;12(1):1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foster E, Jones DE Group CPPR. The high costs of aggression: Public expenditures resulting from conduct disorder. American Journal of Public Health. 2005 October;95(10):1767–1772. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.061424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Costello EJ, Copeland W, Cowell A, Keeler G. Service Costs of Caring for Adolescents With Mental Illness in a Rural Community, 1993–2000. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164(1):36. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.164.9.A36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kessler RC, Heeringa S, Lakoma MD, et al. Individual and Societal Effects of Mental Disorders on Earnings in the United States: Results From the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2008 June 1;165(6):703–711. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08010126. 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scott S, Knapp M, Henderson J, Maughan B. Financial cost of social exclusion: follow up study of antisocial children into adulthood. British Medical Journal. 2001;323(7306):191–194. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7306.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kendler KS, Schmitt E, Aggen SH, Prescott CA. Genetic and Environmental Influences on Alcohol, Caffeine, Cannabis, and Nicotine Use From Early Adolescence to Middle Adulthood. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008 June 1;65(6):674–682. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.6.674. 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O'Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000 Oct 4;284(13):1689–1695. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gennetian LA, Miller C. Children and welfare reform: A view from an experimental welfare program in Minnesota. Child Development. 2002;73:601–620. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wright S. Work response to income maintenance: Economic, sociological, and cultural perspectives. Social Forces. 1975;53:552–562. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burtless G, Hausman JA. Effect of taxation on labor supply: Evaluating the Gary Negative. Journal of Political Economy. 1978;86:1103–1130. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akee R, Copeland W, Keeler G, Angold A, Costello E. Educational attainment, criminality and casino payment: young adult outcomes from a quasi-experiment in Indian country. American Economic Journal. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Evans WN, Topoleski JH. The social and economic impact of Native American casinos. 2002 Published Last Modified Date|. Accessed Dated Accessed|. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Insel TR, Quirion R. Psychiatry as a clinical neuroscience discipline. Jama. 2005 Nov 2;294(17):2221–2224. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.17.2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]