Introduction

Where do intimal smooth muscle cells (SMCs) come from? For many years, the model that intimal smooth muscle cells (SMCs) originated from the underlying media went unchallenged.1 Then reports began to appear that up to half of the SMCs in the intima of atherosclerotic plaques and injured arteries arose from circulating progenitor cells of bone marrow origin.2,3 This new view of intimal SMC formation was potentially important because it raised the possibility of a new class of therapeutic targets for intervention in the process of restenosis based on a bone marrow derivation of intimal SMCs. However as other laboratories began to follow up on these intriguing initial reports, a long-term contribution of bone marrow-derived cells to intimal tissue became less tenable.4,5 In this issue of the ATVB, a careful and detailed study by Daniel et al6 seems to leave little or no room for a role of bone marrow-derived cells as progenitors for the intimal SMCs and endothelial cells that become stable residents of a mature neointima that forms after acute vascular injury.

Long-Term Analysis of Neointimal Formation

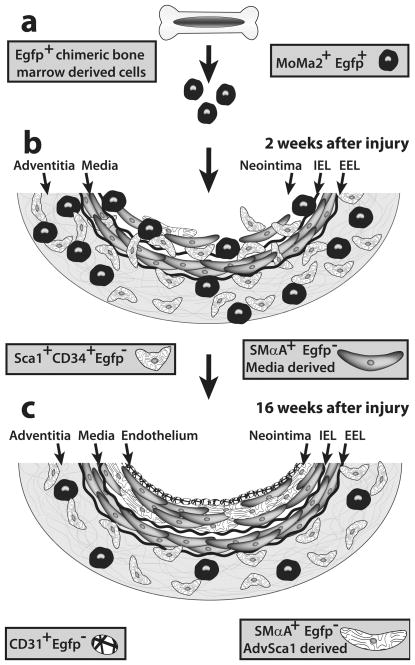

Daniel et al transplanted bone marrow from EGFP-positive (EGFPpos) mice into lethally-irradiated wild type C57Bl/6 mice, allowed 12 weeks for stable engraftment, then carried out wire injury to the femoral artery and recovered injured tissues from 3 days to 16 weeks after injury.6 The extended time course is important because most studies of neointimal formation in this model usually stop at 4 weeks, occasionally 8 weeks, after vascular injury. Daniel et al6 observed a rapid accumulation of EGFPpos cells in neointimal tissue that peaked in the first two weeks after injury and accounted for up to 68% of the total cells in the neointima. However, as cells expressing differentiated SMC markers began to accumulate in the neointima, the numbers of EGFPpos cells in the neointima became markedly diminished. By 16 weeks after injury only 2% of neointimal cells were found to be EGFPpos and very few, if any, of EGFPpos neointimal cells expressed the definitive SMC marker proteins calponin or SM-myosin heavy chain (SM-MHC) (Figure). Likewise, few if any of the CD31pos endothelial cells in the neointima could be assigned a bone marrow origin by 16 weeks after injury. The authors conclude that the contribution of marrow-derived cells to neointimal formation is best viewed as an early paracrine activity that diminishes with time, and that there is little, if any, long-term contribution of marrow-derived progenitors to the endothelial or SMC components of the longstanding neointima.6

Figure.

Bone marrow-derived cells are not stable residents in neointima. a) Chimeric mice transplanted with Egfp-expressing bone marrow cells are subjected to femoral artery injury. b) Two weeks after wire injury, the neointima is composed of MoMa2+ Egfp+ macrophages and stem cell antigen 1 (Sca1)+ CD34+ Egfp− vascular progenitor cells. c) Sixteen weeks after injury, there are no Egfp+ cells in the neointima. The authors hypothesize that many of the neointimal smooth muscle cells in this model originate from locally derived adventitial Sca1+ CD34+ Egfp− cells (AdvSca1). IEL, internal elastic lamina. EEL, external elastic lamina.

Experimental Design and Technical Considerations

Several technical and experimental considerations are important in evaluating why the results of Daniel et al6 reach conclusions that significantly differ from the earlier reports.2,3 One is the use of high-resolution confocal microscopy and deconvolution analysis of Z-axis image stacks. These methods reduce the likelihood of false-positive assignments for EGFP-positive (EGFPpos) cells that appear to expresses SMC marker proteins that are actually expressed by closely apposed cells in tissue cross sections. A second technical consideration is that Daniel et al found rapid fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) was necessary to prevent leakage of the EGFP marker protein from a cell that expressed it in vivo to a neighboring cell that did not.6 If too much time was allowed before fixation, cells in the tissue began to release EGFP, most likely through cell lysis, and the fluorescent marker would diffuse to neighboring binding sites associated with otherwise EGFP-negative (EGFPneg) cells. In addition, an important feature of their experimental design was that the time course was extended up to 16 weeks after arterial injury. This extended time course allowed for a clear distinction between an early, inflammatory phase occurring in the first two weeks after injury when the neointima contained a large component of EGFPpos/MoMa2pos macrophages, and a late, mature phase from 4 weeks to 16 weeks in which EGFPpos cells were lost and EGFPneg cells expressing SMαActin as well as the definitive SMC marker proteins (calponin, SM-MHC) became abundant (Figure). The results of the study by Daniel et al6 strongly suggest that the role of bone marrow-derived cells in neointimal formation is primarily a transient paracrine one rather than as a precursor population for transdifferentiation into long-term resident endothelial cells and SMCs in neointimal tissue.

Origins of Neointimal SMCs

What then is the origin of SMCs in the longstanding neointima? In simpler times, the finding that bone marrow-derived progenitors do not serve as a significant source of neointimal SMCs would lead to the familiar conclusion that medial SMCs are the source of intimal SMCs. Except in extreme models of transplant graft rejection, where essentially all of the medial cells in the graft are lost through cell death, there is little argument that at least some neointimal SMCs originate in the injured media. However, the media is not the only source of cells from which the injured artery wall can build a neointima. Over the years, there have been occasional reports about a possible role for the adventitia in neointimal formation. For many investigators these reports were seen as inconsistent with existing dogma and their conclusions were frequently ignored. However, it is hard to deny that the adventitia is highly responsive to most forms of arterial injury. Indeed, there appears to be a continuous communication between the endothelium and the adventitia by use of transmural mediators whose molecular identity has not yet been characterized. For example, Scott et al7 reported that a majority of proliferating cells in porcine coronary arteries subjected to overstretch injury was found in the adventitia. Injections of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) given between days 2 and 3 after injury showed that proliferating adventitial cells can migrate into the neointima where they were found by day 14 after injury.7 Similar results were reported by Shi et al8 using a saphenous vein graft model. Likewise, in a rat carotid balloon injury model in which adventitial fibroblasts are labeled in vitro with a retrovirus expressing β-galactosidase (β-gal) and then introduced into carotid adventitia immediately after injury,β-gal-positive cells were found in the injured media at 5 days and in the neointima at 7, 10 and 14 days after injury.9 A review of the literature in 2001 led Sartore et al10 to hypothesize that in response to adult vascular injury, activation of adventitial fibroblasts is, at least in part, reminiscent of a developmental program that invests medial SMCs around newly forming blood vessels.

Formation of Adventitia in Vascular Development

The suggestion of a link between mechanisms used to construct artery walls in the embryo and the formation of a neointima in adult vessels raises a number of intriguing questions, particularly with respect to the adventitia. It is well documented that hypertensive remodeling of the hypoxic pulmonary artery results in dramatic wall thickening including formation of additional smooth muscle layers. These additional layers form on the adventitial side of the artery wall and may well utilize SMCs that originate from local progenitors that are natural residents in the adventitia.11 Similarly, in mice haploinsufficient for tropoelastin (ELN), additional alternating layers of SMCs and elastic fibers are formed on the adventitial side of the artery wall during late stages of embryogenesis around E15.5 to E18.5.12,13 These new SMCs are formed well after the initial cohort of SMC progenitors from cardiac neural crest and other early embryonic sources has completed investment of artery walls from E10.5 to E14.5.14 A potential source of SMCs that are added to the outside of the artery wall was identified by Hu et al15 and confirmed by Passman et al16. These papers showed that a population of stem cell antigen 1 (Sca1)-positive cells in the adventitia (AdvSca1) could be isolated by immunomagnetic selection or FACS sorting for Sca1 expression and found that a significant fraction of these progenitor cells differentiated to SMCs in vitro. These AdvSca1 progenitor cells clustered in the border region between the media and adventitia.16 When transplanted to the outside of a vein graft, AdvSca1 cells were found in the media at 2 weeks and in the neointima at 4 weeks after transplant where they comprised about 20% of the total neointimal cell population.15 AdvSca1 cells normally appear at about E16.5 to E17.5 in the aortic adventitia and then are found throughout the arterial system.16 They are not bone marrow-derived.15 Their initial appearance and/or survival in the embryonic aortic adventitia is dependent upon sonic hedgehog signaling in the adventitial layer.16 In this same border region between the media and adventitia of human internal thoracic artery (HITA) specimens, a population of CD34pos/PECAM1neg cells is found that can form capillary-like microvessels when segments of HITA are explanted in an aortic ring assay.17

Summary and the Road Ahead

Taken together, these reports suggest that the arterial adventitia contains a resident population of vascular progenitor cells with the capability to differentiate into SMCs and to migrate from the adventitia to the developing neointima. Indeed, Daniel et al6 report identification of a highly proliferative fraction of Sca-1pos/CD34pos cells in the femoral artery adventitia that was EGFPneg and therefore locally-derived. Moreover, at 6 weeks after wire injury, individual Sca1pos/CD34pos cells were found within the media apparently migrating from the adventitia to the neointima, similar to the findings of Hu et al.15 These results provide further support for the conclusions of Wagers et al18 that bone marrow-derived hematopoietic stem cells exhibit little or no plasticity for transdifferentiation into the principle cell types that make up the vessel wall (endothelial cells and SMCs). The unique properties of intimal SMCs argue for a unique origin for these cells.19 The work of Bentzon et al4 and Daniel et al6, among others, suggests that an origin of intimal SMCs from circulating progenitors of bone marrow origin is highly unlikely. Persistent reports of adventitial cell proliferation after arterial injury6,7, the movement of these cells into the intima7,9,15, and the formation of a vascular progenitor cell niche at the border between the media and adventitia in embryonic development15–17 argue for a closer look at the roles played by adventitial cells in formation of a neointima and in pathogenesis of intimal disease.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by NIH grants HL-93594 and HL-19242 (to MWM), by American Heart Association Fellowship 09PRE2060165 (to VJH) and by the Curriculum in Genetics & Molecular Biology Training Program, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

We thank our colleagues Jenna Regan and James Faber at the University of North Carolina; as well as Alexander W Clowes, Mary Weiser-Evans, Joseph M Miano, and Stephen M Schwartz for helpful discussions.

References

- 1.Clowes AW, Reidy MA, Clowes MM. Mechanisms of stenosis after arterial injury. Lab Invest. 1983;49:208–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saiura A, Sata M, Hirata Y, Nagai R, Makuuchi M. Circulating smooth muscle progenitor cells contribute to atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2001;7:382–383. doi: 10.1038/86394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sata M, Saiura A, Kunisato A, Tojo A, Okada S, Tokuhisa T, Hirai H, Makuuchi M, Hirata Y, Nagai R. Hematopoietic stem cells differentiate into vascular cells that participate in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2002;8:403–409. doi: 10.1038/nm0402-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bentzon JF, Weile C, Sondergaard CS, Hindkjaer J, Sassem M, Falk E. Smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis originate from the local vessel wall and not circulating progenitor cells in ApoE knockout mice. Arterioscl Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2696–2702. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000247243.48542.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoofnagle MH, Thomas JA, Wamhoff BR, Owens GK. Origin of neointimal smooth muscle: We’ve come full circle. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2579–2581. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000249623.79871.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daniel J-M, Bielenberg W, Stieger P, Weinert S, Tillmanns H, Sedding DG. Time course analysis on the differentiation of bone marrow derived progenitor cells into smooth muscle cells during neointima formation. Arterioscl Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:xxx–yyy. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.209692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott NA, Cipola GD, Ross CE, Dunn B, Martin FH, Simonet L, Wilcox JN. Identification of a potential role for the adventitia in vascular lesion formation after balloon overstretch injury of porcine coronary arteries. Circulation. 1996;93:2178–2187. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.12.2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi Y, O’Brien JE, Mannion JD, Morrison RC, Chung W, Fard A, Zalewski A. Remodeling of autologous saphenous vein grafts: The role of perivascular myofibroblasts. Circulation. 95:2684–2693. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.12.2684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li G, Shen SJ, Oparil S, Chen YF, Thompson JA. Direct in vivo evidence demonstrating neointimal migration of adventitial fibroblasts after balloon injury of rat carotid arteries. Circulation. 2000;101:1362–1365. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.12.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sartore S, Chiavegato A, Faggin E, Franch R, Puato M, Ausoni S, Pauletto P. Contribution of adventitial fibroblasts to neointimal formation and vascular remodeling: from innocent bystander to active participant. Circ Res. 2001;89:1111–1121. doi: 10.1161/hh2401.100844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stenmark KR, Davie N, Frid M, Gerasimovskaya E, Das M. Role of the adventitia in pulmonary vascular remodeling. Physiology. 2006;21:134–145. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00053.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li D, Faury G, Taylor D, Davis E, Boyle W, Mecham R, Stenzel P, Boak B, Keating MT. Novel arterial pathology in mice and humans hemizygous for elastin. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1783–1787. doi: 10.1172/JCI4487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faury G, Pezet M, Knutsen R, Boyle W, Heximer S, McLean S, Minkes R, Blumer K, Kovacs A, Kelly D, Li D, Starcher B, Mecham RP. Developmental adaptation of the mouse cardiovascular system to elastin haploinsufficiency. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1419–1428. doi: 10.1172/JCI19028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Majesky MW. Developmental basis of vascular smooth muscle diversity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1248–1258. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.141069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu Y, Zhang Z, Torsney E, Afzal AR, Davison F, Metzler B, Xu Q. Abundant progenitor cells in the adventitia contribute to atherosclerosis of vein grafts in ApoE-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1258–1265. doi: 10.1172/JCI19628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Passman JN, Dong XR, Wu SP, Maguire CT, Hogan KA, Bautch VL, Majesky MW. A sonic hedgehog signaling domain in the arterial adventitia supports resident Sca1+ smooth muscle progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9349–9354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711382105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zengin E, Chalajour F, Gehling UM, Ito WD, Treede H, Lauke H, Weil J, Reichenspurner H, Kilic N, Ergun S. Vascular wall resident progenitor cells: a source for postnatal vasculogenesis. Development. 2006;133:1543–1551. doi: 10.1242/dev.02315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagers A, Sherwood RI, Christensen JL, Weissman IL. Little evidence for developmental plasticity of adult hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 2002;297:2256–2259. doi: 10.1126/science.1074807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwartz SM, de Blois D, O’Brien ERM. The intima: soil for atherosclerosis and restenosis. Circ Res. 1995;77:445–465. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]