Abstract

Symplastic spermatids (sys) male mice are sterile due to a recessive mutation that causes defective adhesion between spermatids and Sertoli cells within the seminiferous epithelium. We show that the mutation in sys mice involves a deletion of 1.24 Mb of chromosome 14. Comparative genomic analysis suggests that this region contains only one gene, Fndc3a. A genetic complementation analysis using mice with a specific mutation within Fndc3a verifies that mutation of Fndc3a is the cause of male sterility in sys mice. Fndc3a is a member of a three-gene family in mice. Fndc3a, which is expressed in several tissues including testis, encodes a novel protein composed of a proline-rich amino-terminus, nine fibronectin type-III domains, and a hydrophobic carboxy-terminus. The proline-rich region of each family member contains conserved amino acids that include a PPGY consensus binding site for type I WW domain containing proteins. The hydrophobic carboxy-terminus is similar to that found in ‘tail-anchored’ proteins, integral membrane proteins that are localized to the cytosolic face of the endoplasmic reticulum. Immunohistochemical staining indicated that FNDC3A localizes to the acrosome of spermatids, as well as to Leydig cells in the mouse testis. Acrosomal localization of FNDC3A is observed in spermatids between step 2 and step 10 inclusive. In step 12 spermatids, FNDC3A is largely absent from the acrosomal region with immunostaining being localized to vesicular structures located within the cytoplasm of elongate spermatids. Models are presented for the function of FNDC3A in mediating spermatid–Sertoli adhesion during mouse spermatogenesis.

Keywords: Sterility, Fndc3a, Acrosome, Leydig, Sertoli, Spermatid, Adhesion

Introduction

Spermatogenesis produces haploid gametes that transmit genetic information from the male to the next generation. In adult mammals spermatogenesis occurs in three phases (de Kretser and Kerr, 1988). During the first phase, spermatogonial stem cells divide to produce type A spermatogonia that undergo a series of mitotic divisions to form an amplified population of type B spermatogonia. During the second phase, the type B spermatogonia undergo meiosis to produce haploid round spermatids that contain new assortments of alleles of parental genes. The third phase of spermatogenesis, called spermiogenesis, involves a dramatic differentiation of the round spermatids into elongate mature spermatids. These contain highly compacted DNA, a specialized propulsion system and the acrosome, a modified secretory compartment required for fertilization of an oocyte. Throughout spermatogenesis, developing germ cells undergo complete karyokinesis but incomplete cytokinesis, and daughter cells are connected via cytoplasmic bridges of a few microns in diameter. The syncytial nature of mammalian spermatogenesis facilitates synchronicity of germ cell development and death, in addition to sharing of gene products within a clone (Braun et al., 1989; Hamer et al., 2003). In vertebrates, spermatogenesis is supported by the Sertoli cell, a specialized epithelial cell that is the only somatic cell within the seminiferous epithelium (Russell and Griswold, 1993). The Sertoli cell is essential for spermatogenesis. Important functions for Sertoli cells include providing a nutritive environment for germ cell development, formation of inter-Sertoli tight junctions that form the “blood” (lymph) testis barrier that separates spermatogonia from meiotic and post-meiotic male germ cells, and regulation of numbers of mature spermatids produced (Russell and Griswold, 1993). Throughout spermatogenesis, Sertoli cells maintain contact with germ cells via communicating and adhesive junctions (Mruk and Cheng, 2004b). Control of adhesive junction function is critical to spermatogenesis. It is presumed that release of germ cells prior to maturation produces germ cells that are incapable of fertilizing oocytes. Conversely, failure to release mature spermatids at the correct stage of spermatogenesis can cause sterility, with the mature germ cells being phagocytized by the Sertoli cell.

Our laboratory is interested in identifying gene products required for mammalian spermatogenesis and understanding their function in this process. Random insertional mutagenesis is a powerful approach to identify genes whose function is required for a specific biological process in mammals (Meisler, 1992; Rijkers et al., 1994; Stanford et al., 2001). Previously, we described symplastic spermatids (sys) mice that have a recessive mutation that causes sterility in males (MacGregor et al., 1990). The sterility is associated with abnormal loss of adhesion between spermatids and Sertoli cells, which occurs when round spermatids reach step 8 of spermiogenesis (MacGregor et al., 1990; Russell et al., 1991a). Analysis of chimeric mice generated by aggregation of sys mutant and wild-type pre-implantation embryos suggested that the genetic defect in sys mice affects a cell type within the testis (MacGregor, 2002). Consequently, we have focused on identifying genes that are expressed in testis and which are mutated in sys mice. Such genes are candidates for the gene whose mutation affects spermatid–Sertoli adhesion (Mruk and Cheng, 2004b).

The sys line of transgenic mice was generated by pronuclear microinjection of a RSV-lacZ transgene (MacGregor et al., 1990). Molecular analysis of transgenic mice generated in this manner indicates that integration of a transgene complex is often accompanied by rearrangement of the genome, including deletions, duplications, or inversions, at or close to the site of integration (Rijkers et al., 1994). This can make it laborious to identify the gene defect responsible for recessive mutant phenotypes observed in these strains of mutant mice (Headon and Overbeek, 1999; Mochizuki et al., 1998; Qin et al., 2004; Zhou et al., 1995). Completion of the mouse genome has greatly simplified such molecular analyses. We used this resource to characterize the mutation in sys mice and to identify candidates for the gene defect responsible for the recessive male sterility. Here, we define the molecular mutation in sys mice and use genetic complementation analysis to demonstrate that mutation of fibronectin type III domain containing 3a (Fndc3a) is responsible for the male sterility observed in sys mice. FNDC3A is expressed within spermatids, where it is localized to the acrosome, and in Leydig cells. Models are presented for the function of FNDC3A in mediating adhesion between spermatids and Sertoli cells.

Materials and methods

Mice

The sys line of transgenic mice was generated by microinjection of a RSV-lacZ transgene into the pronucleus of a F1 FVB/N×C3H fertilized oocyte (MacGregor et al., 1990). The sys mutation has been backcrossed from the original C3H×FVB/N F1 strain background on to a C57BL/6 (B6) background for 12 generations where the recessive mutant male-sterility phenotype remains fully penetrant.

Production of mice with gene-trap mutations in Fndc3a

We identified mouse embryonic stem (ES) cell clones containing a gene-trap mutation within the Fndc3a locus using the BayGenomics resource (http://baygenomics.ucsf.edu/). The RRP208 ES cell line contains the pGT0Lxf gene trap vector integrated within the 53 kb intron 3 of Fndc3b. This ES cell line was provided by BayGenomics, via the Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Center at UC Davis. Prior to use, the location of the gene-trap insertion within Fndc3a in the RRP208 ES cell line was verified by 5′ RACE PCR and sequencing by BayGenomics. The ES cells were propagated on feeder layers prepared from SNL76/7 cells, and chimeric mice generated by microinjection of blastocyst stage C57BL/6J embryos with between 10 and 15 ES cells each as described (MacGregor et al., 1995). Chimeric males were outcrossed to C57BL/6J mice and F1 heterozygous Fndc3aRRP208 animals were identified using PCR with primers against the lacZ and En2 intron sequence and conditions described on the BayGenomics web site.

Analysis of nucleic acids

For Southern analysis, genomic DNAs from wild-type and sys homozygous mice were digested with BamHI and EcoRI, subjected to electrophoresis through a 0.8% TAE agarose gel and transferred to nylon membranes in 0.4 M NaOH as described (Ausubel et al., 1994). For northern analysis, RNA was isolated from adult mouse testes by guanidium thiocyanate extraction (Ausubel et al., 1994). For each sample, 15 μg of total RNA was denatured by treatment with formamide and electrophoresed through a formaldehyde agarose gel as described (Ausubel et al., 1994). The blots in figure two were hybridized with a 32P-dCTP labeled 1270 bp cDNA probe derived from the extreme 3′ UTR of Fndc3A (nuc # 4869-6139).

Generation of full-length cDNA for Fndc3a

A full-length mouse Fndc3a cDNA was generated by ligation of two ESTs, AI415377 and BU506357. A MscI/XhoI double digest was performed on both ESTs and the 0.3 kb MscI/XhoI fragment was removed from AI415377 and replaced by ligation of the gel purified 5.5 kb MscI/XhoI fragment from BU506357. Overlapping primers were used to sequence both strands of the cDNA and a contig was assembled using Sequencer DNA analysis software (Gene Codes Corp., Ann Arbor, MI). The consensus sequence was compared to genomic and EST databases by BLAST analysis (Altschul et al., 1990).

Comparative genomic analysis using PipMaker

PipMaker (Schwartz et al., 2000) available at (http://pipmaker.bx.psu.edu/pipmaker/) was used to compare mouse and human genomic sequence. The parameters used were a minimum of 70% identity over a window of at least 100 bp. These parameters are effective at identifying both coding and noncoding exons of genes when mouse and human genomes are compared.

Construction of FNDC3A-PRR expression vector, purification of recombinant protein from bacteria, and production of anti-FNDC3A polyclonal antisera

A bacterial expression system was used to produce FNDC3A recombinant protein for immunization. FNDC3A recombinant protein was generated by PCR amplification of the Fndc3a cDNA, BU506357, with the following primer pair: forward (5′-cgggattaatATGTACTCACCAGTGACTGGAGCTG-3′); reverse (5′-tgtaggatccGAGGCCACTGGCTTGACAATGTTGG-3′). The nucleotides in lower case represent AseI and BamHI linkers on the forward and reverse primers respectively and the nucleotides in upper case are Fndc3a-specific. The 420 nt amplification product, representing amino acids 137 to 276 in the amino-terminus of FNDC3A, was digested with AseI and BamHI and gel purified. The pET19b expression vector (Novagen; Madison, WI) was digested with NdeI and BamHI and gel purified. Using the TA overhang provided by the AseI digest, the 420 nt Fndc3a fragment was ligated to the NdeI and BamHI digested pET19b vector. The resulting vector (pET-FNDC3A), encodes a 139 amino acid FNDC3A polypeptide fused with an amino-terminal His10 epitope tag. Recombinant FNDC3A protein was expressed in a BL21 (DE3) host and purified by nickel ion metal affinity chromatography (Amersham Biosciences; Piscataway, NJ). Polyclonal FNDC3A-specific antisera were generated by immunization of rabbits with recombinant protein. Covance Research Products (Denver, PA) performed all immunizations and collection of sera.

Histology of testis and epididymis, and analysis of content of vas deferens

For periodic acid Schiff (PAS) reaction, the isolated testes and epididymides were fixed for 4 h in Bouin’s fluid (prepared fresh each month) at 4°C. Testes were removed and each pole (around 10% of each testis) was removed using a fresh microtome blade. Testes were re-immersed in Bouin’s fluid and left at 4°C for 16–24 h. After dehydration in ethanol, and embedded in paraffin (Paraplast Plus, Tyco Healthcare, Mansfield, MA), serial sections, either 5 or 7 μm in thickness, were cut and stained with PAS reagent as described (Ross et al., 1998). Nuclei were counterstained by immersion for 2 s in undiluted Harris’ hematoxylin with glacial acetic acid (Polyscientific, Bay Shore, NY).

Vasa deferentia were dissected and their contents extruded by holding one end with watchmaker forceps (Dumont #5) while gently squeezing the structure along its length using a second, closed, pair of watchmaker forceps. The contents were dispersed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1 μg/ml 4′-6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to stain nucleic acids, mounted with a coverslip, and examined using a microscope (Axiovert 200M, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with fluorescence and differential interference contrast (DIC) optics.

Immunohistochemistry

Testes were dissected and fixed in Bouin’s fluid as described for general histology. Testes were cryoprotected by incubation in 30% sucrose w/v in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and frozen in Optimal Cutting Temperature (OCT) compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA). Twelve-micron sections were cut on a cryostat, mounted onto slides, air dried for 10 min, fixed in ice-cold acetone for 15 min, and rinsed in water for 5 min. To block endogenous peroxidase activity, prior to immunohistochemistry sections were immersed for 10 min in a solution containing 0.3% H2O2 and 0.3% normal goat sera in PBS followed by two 5-min rinses in PBS. Immunohistochemistry was performed using Vectastain Elite ABC peroxidase kit (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with the following modifications. The wash buffer was PBS and 0.1% Triton X-100 and sections were incubated for 45 min with FNDC3A antisera #2000 (1:100) at room temperature. Immuno-stained sections were counter-stained with hematoxylin.

Enrichment of germ cells from mouse testis

Adult male ICR mice were obtained from Harlan Sprague–Dawley Inc. (Indianapolis, IN). Enriched germ cell fractions were separated by unit gravity sedimentation on a 2%–4% BSA gradient as described (Bellve, 1993). Enrichment of preparations (i.e. percentage of specific cell type) was quantified using differential interference microscopy (Bellve, 1993). The purity of round spermatids was 86%, with the major contaminant being residual bodies and cytoplasts. The residual body preparation was 88% pure, while the pachytene preparations used were 60% (low-enriched) and 89% (high-enriched).

Reverse-transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis of Fndc3a expression

Total RNA was isolated from testicular samples using acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform as described (Campbell et al., 2002). Testicular expression of Fndc3a, Hprt, and Fndc3aβ-geo fusion mRNAs was assessed by RT-PCR using specific primer pairs. The Fndc3a primers, C (5′-ATAAG-TACGGTGGTGGAGATGGCAG-3′) and D (5′-ATCCACCATCAACCT-GAGGAGGTC-3′) flank a 285 nt region within the Fndc3a coding sequence (Fig. 5A). To detect the Fndc3aβ-geo fusion transcripts, the following primers were used: forward, A (5′-ATTGATAATGGCAGAACACCCGCC-3′), specific for exon two of Fndc3a, and reverse, B (same primer used in genotyping) that produce a 754 nt amplification product (Fig. 5A). As an internal control, amplification of a fragment of Hprt mRNA was carried out in parallel in each sample, using the primer pair: forward (5′-CCTGCTGGATTACATTAAAG-CACTG-3′) and reverse (5′-GTCAAGGGCATATCCAACAACAAAC-3′). Complementary DNA was synthesized from 2 μg of total RNA using 200 U SuperScript III-reverse transcriptase (RT) (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA), 40 U ribonuclease inhibitor RNase-Out (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA), and 150 ng random hexamer primers, in a total volume of 20 μl. RT reactions were incubated at 25°C for 5 min, at 50°C for 1 h, and were terminated by heating at 70°C for 15 min. PCR amplification of cDNAs (diluted 1:10) was carried out in 30 μl of 1× PCR buffer in the presence of 1 U Taq-DNA polymerase (Promega; Madison, WI) and 1 nM forward and reverse primers. The PCR cycle for Fndc3a and Fndc3ab-geo fusion were: denaturation at 95°C for 20 s, annealing at 55°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 1 min for 35 cycles. The PCR cycle for Hprt was: denaturation at 95°C for 20 s, annealing at 63°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 1 min for 35 cycles.

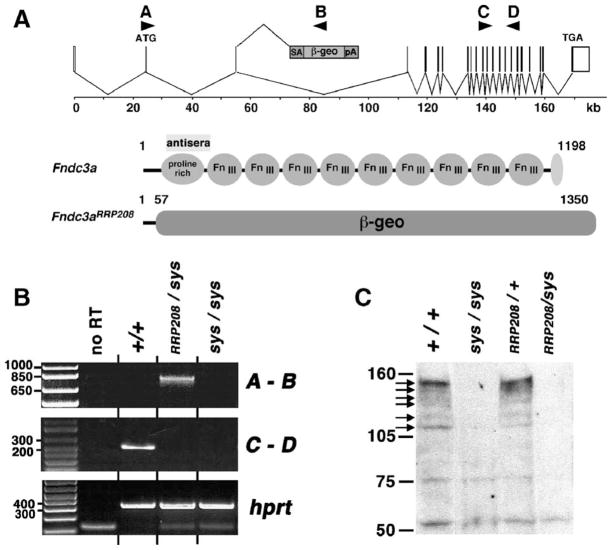

Fig. 5.

Molecular analysis of RRP208 gene-trap mutant allele of Fndc3a. (A) The upper part of the figure depicts the mouse Fndc3a locus consisting of 27 exons distributed over 170 kb of mouse chromosome 14. The translational start (ATG) and stop (TGA) sites are indicated. In the RRP208 ES cell line, analysis by 5′RACE indicates that the pGT0lxf gene trap vector integrated within intron 3, which is approximately, 52 kb in size. The arrowheads labeled A–D indicate the location of sequence used to design PCR primers for the RT-PCR analysis. Also depicted are the predicted products encoded by the wild-type (Fndc3a) and gene-trap (Fndc3aRRP208) mutant allele of Fndc3a. FNDC3A contains three domains, an amino-terminal proline rich region, a central region with nine fibronectin type-III domains, and a hydrophobic carboxy-terminus. The Fndc3aRRP208 allele is predicted to encode a fusion protein consisting of the first 57 amino acids of FNDC3A fused to the chimeric E. coli beta-galactosidase –neomycin aminophosphotransferase (β-geo) reporter protein. The theoretical molecular weight of FNDC3A is 132 kDa. The polyclonal rabbit anti-FNDC3A antisera used in the study was raised using recombinant protein consisting of amino acids #137 to 276 of mouse FNDC3A. (B) RT-PCR analysis of mRNA transcripts in testis of wild-type and Fndc3a mutant mice. PCR Primers A–B amplify a 754 bp fusion product between exon 2 of Fndc3a and lacZ of the β-geo reporter gene, which is detected using RNA isolated from the testis of an animal with an Fndc3aRRP208 allele, but not in a wild-type or sys homozygote mouse. Primers C–D amplify a 285 bp product of cDNA from exons 16 to 19 of Fndc3a. The lower panel is a positive control for input cDNA in the RT-PCR reaction, involving amplification of coding sequence for hprt. No RT=negative control demonstrating lack of amplification products in the absence of reverse transcriptase. All other “no RT” reactions gave an essentially identical result (not shown). (C) Western analysis of total testicular protein from wild-type and Fndc3a mutant mice. Six FNDC3A-specific products are indicated by black arrows on the left side of the figure. These products are observed in different ratios in independent tissues (unpublished results). Each of the six products is absent in protein extracts from testes of Fndc3asys homozygous and Fndc3asys/Fndc3aRRP208 compound heterozygous mice. The band of approximately 52 kDa that reacts in a nonspecific manner with the antisera provides an estimate of the relative amount of total protein loaded per lane.

Western analysis

Adult mouse tissues were homogenized in lysis buffer composed of 10 mM Tris pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% NP40, and “Complete” mini protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Applied Science; Indianapolis, IN). Protein concentration was determined using Bradford protein assay reagent (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard. The protein lysate (15 μg) was subjected to electrophoresis through 3–8% acrylamide–Tris–Acetate–EDTA (TAE) gels (Invitrogen) at 150 V for 1 h 30 min in 1× TAE buffer and transferred to polyvinlylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes at 30 V for 1 h in 1× transfer buffer (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The membrane was blocked for 2 h at room temperature with ECL Advance blocking buffer (Amersham Biosciences; Piscataway, NJ) according the manufacturer’s instructions. The membrane was incubated with primary antibodies in ECL Advance blocking buffer for 45 min at room temperature. Primary antibody, rabbit polyclonal FNDC3A #2000 was used at a final concentration of 1:2000. The membrane was washed for 30 min with three changes of PBST (PBS pH 7.3 and 0.1% Tween 20) then incubated in a 1:100,000 dilution of donkey anti-rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibody (GE-Amersham Biosciences) at room temperature for 1 h. The membrane was then washed for 40 min with four changes of PBST and processed for development using ECL Advance substrate (GE-Amersham Biosciences) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Membranes were stripped and re-probed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Comparison of FNDC3 family protein sequences

Alignment of FNDC3A family sequences was performed using CLUS-TALW algorithm (Thompson et al., 1994), followed by manual inspection to minimize gaps and maximize homology.

Results

Delineation of the molecular mutation in sys mice

The transgene complex in sys mice consists of approximately 20 copies of a Rous sarcoma virus long-terminal repeat promoter- lacZ mini-gene, integrated as a head to tail concatemer at a single site on mouse chromosome 14 (MacGregor et al., 1990). Previously, the genomic DNA flanking each side of the transgene complex was cloned and the centromere-proximal flank was used as a starting point to perform a genomic ‘walk’ (MacGregor and Overbeek, 1991; MacGregor et al., 1990). The results indicated that presence of the transgene array was associated with deletion of at least 375 kb of genomic DNA at the transgene integration site (MacGregor and Overbeek, 1991; MacGregor et al., 1990). The genomic DNA from this 375 kb interval was analyzed for evidence of exon containing sequence by zoo-blot and Northern analyses but none was found (GRM, D.T. Gilmour and P.A. Overbeek, unpublished results). This suggested that no transcribed gene was located within the 375 kb interval. Previous efforts to analyze this mutation were hampered by the finding that the genomic DNA sequence from the distal flank of the site of integration of the transgene complex could not be propagated in bacteria (MacGregor and Overbeek, 1991).

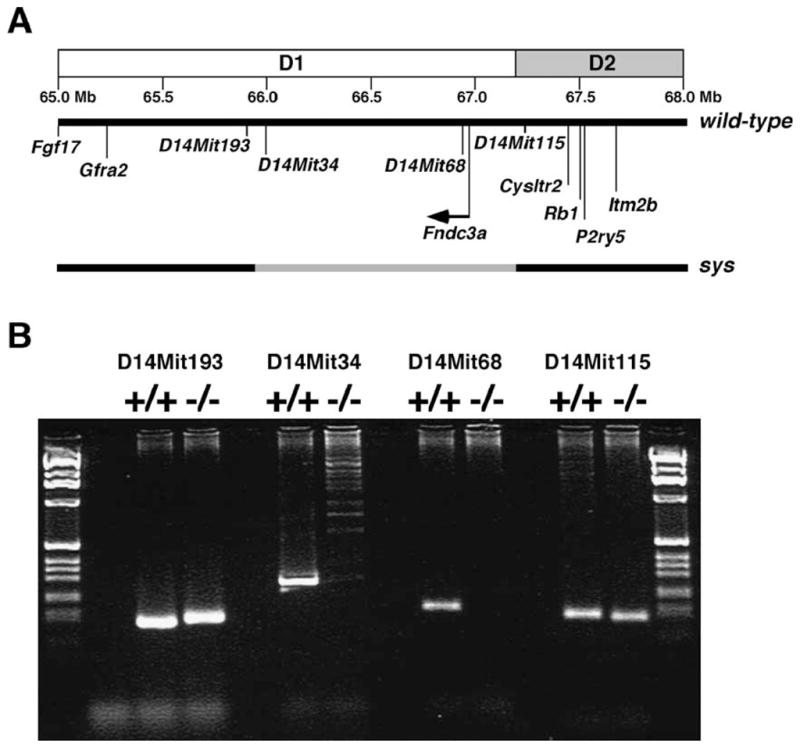

Completion of the mouse genomic DNA sequence facilitated further analysis of the sys mutation. To determine the size of the deletion of genomic DNA on chromosome 14, genomic DNA adjacent to each side of the transgene complex from sys mice was sequenced and this used to perform a BLAST analysis against the mouse genome sequence (Ensembl database, version 38). The results indicate that sys mice have a deletion of 1.24 Mb of chromosome 14 (Fig. 1). The simplest model for the genetic lesion in sys mice involves a deletion of the genomic DNA located between the flanks of the transgene integration site. To test this model, we used PCR to screen for the presence of unique genomic DNA sequences that map to this interval. Consistent with the model, loci defined by D14Mit34, D14Mit68, and D14Mit192 (not shown) were each deleted in the sys allele of chromosome 14, while D14Mit193 and D14Mit115, two loci that lie outside the flanks of the transgene integration site, were present (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Molecular analysis of the chromosomal mutation in sys mice. (A) The region of mouse chromosome 14 bands D1–D2 in the vicinity of the sys mutation is shown. The region of the genome deleted in sys mice is indicated in grey. (B) An example of PCR analysis of microsatellite markers located in this region of chromosome 14 using either wild-type or homozygous mutant sys DNA as template. D14Mit34, D14Mit68, and D14Mit192 (data not shown) are deleted in sys homozygote mice.

Fndc3a is deleted in sys mice and is expressed in mouse testis

Inspection of the mouse genome database (Ensembl version 38) revealed two loci, a U1 noncoding RNA involved in RNA processing and Fndc3a, located within the region of the genome deleted in sys mice. Fndc3a encodes a unique protein within the genome, while there are multiple U1-RNA noncoding RNA genes (data not shown). Thus, we rationalized that loss of function of Fndc3a was more likely to be the underlying cause of male sterility in sys homozygous mice. A previous analysis of chimeric mice generated by fusion of sys homozygote and wild-type embryos suggests that the cause of male sterility in sys mice is the result of loss of function of a gene that is normally expressed in the testis (MacGregor, 2002). Consequently, we investigated whether Fndc3a was expressed in mouse testis.

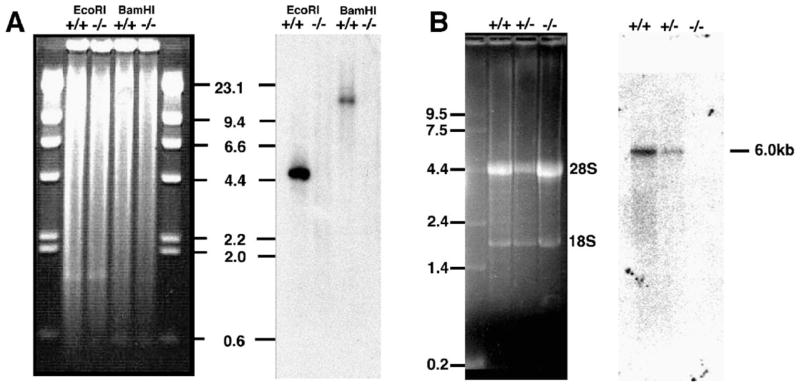

Analysis using the predicted transcript for Fndc3a identified 238 independent ESTs within the mouse dbEST. Almost all clones shared a minimum of 96% identity with the predicted transcript and many displayed 100% identity, including those generated from mouse testicular tissue (data not shown). To verify that Fndc3a is deleted in the sys line of mice and to verify that the gene is expressed in testis, we performed Southern and northern analyses using genomic DNA and total testicular RNA from wild-type and sys homozygous mice in conjunction with a probe generated from a partial-length Fndc3a cDNA (Fig. 2). The results of the Southern analysis verified that Fndc3a is deleted in the sys mutant allele (Fig. 2A). In the adult testis, the probe detects a single mRNA species of approximately 6.0 kb (Fig. 2B). As anticipated, the Fndc3a transcript was not detected in total RNA isolated from testes of sys homozygous animals.

Fig. 2.

Fndc3a is deleted in sys mice and is expressed in wild-type adult male testis. (A) Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA from wild-type and sys mice using a Fndc3a mouse cDNA as a probe. The hybridization signals for Fndc3a are absent in lanes containing genomic DNA from sys homozygous mutants (−/−). (B) Northern blot analysis of total RNA from testes of wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous sys mice. Left panel; gel was stained with ethidium bromide. Right panel; blot hybridized with a cDNA probe representing nucleotides 4869–6139 of Fndc3a. This probe detects an Fndc3a-specific transcript of approximately 6 kb in size in testis RNA from wild-type and heterozygous sys mice but no transcript in testicular RNA from homozygous sys mutants.

Comparative genomic analysis of the region of chromosome 14 deleted in sys mice suggests that Fndc3a is the only gene deleted

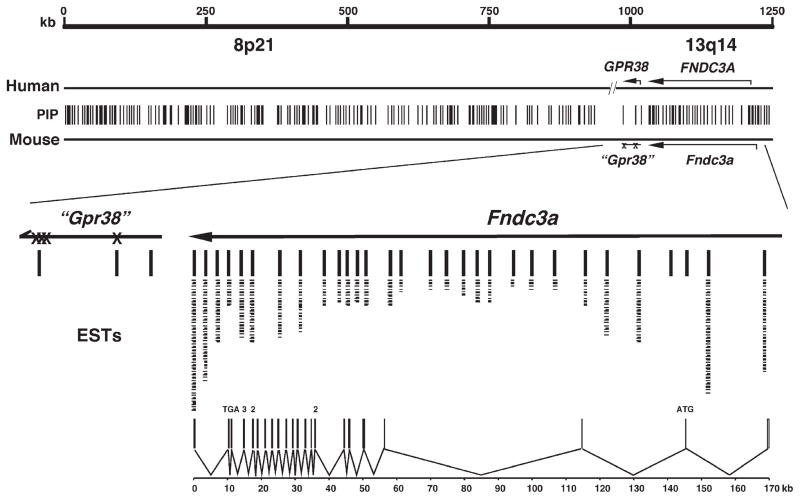

Comparative genomic analysis is a powerful method to identify regions of functional importance in related genomes (Cooper and Sidow, 2003). It is well established that such conserved sequences are often exons or control regions of genes that have related function in each species. As an unbiased method to investigate if Fndc3a is the only gene located in the region of mouse chromosome 14 that is deleted in sys homozygous mice, we compared the region of the mouse genome deleted in the sys allele with the homologous region from the human genome using PipMaker (Schwartz et al., 2000). This algorithm identified 223 independent areas of the mouse genome within this region that each shared a minimum of 70% identity, over at least 100 bp, with the homologous region of the human genome (Fig. 3). To determine if any of these sequences was expressed in mice, each sequence was subjected to BLAST analysis using NCBI’s mouse expressed sequence tag database (dbEST). Twenty-eight of the 223 sequences matched homologous sequences from the mouse dbEST (Fig. 3). Comparison of these 28 sequences with the Ensembl mouse and human genome databases indicated that 26 of the sequences had identity with known exons for Fndc3a. One exon of Fndc3a is smaller than 100 bp and was not detected using the selected settings for the PipMaker analysis. Two of the 28 sequences that did not identify an EST were located within intron 3 of the Fndc3a locus. These conserved sequences may represent cis-regulatory control elements for this locus. Mouse Fndc3a contains 27 exons, distributed over 170 kb on mouse chromosome 14, band D1 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Comparative genome analysis of the 1.2 Mb region of chromosome 14 deleted in sys mice with human 8p21 and 13q14 suggests that Fndc3a is the only gene mutated in sys mice. The scale shown is for mouse chromosome 14. Vertical lines (PIP) represent the 223 pairwise alignments of conserved DNA (>75% identity over >100 bp) as identified using PipMaker (http://pipmaker.bx.psu.edu/pipmaker/). Of the 223 conserved regions, only those within the Fndc3a locus had identity to mouse ESTs as determined by BLAST analysis. Individual ESTs are represented by a dash under the conserved regions. Lines are used to indicate identity between Fndc3a exons and the respective ESTs and conserved regions. Two regions at the 5′ end of Fndc3a are conserved between human and mouse but did not identify an EST in the database. These sequences are not found in the predicted full-length Fndc3a cDNA, have no ORF, and may therefore represent control elements for this locus. (X)—denotes nonsense mutations within the region of mouse chromosome 14 (“Gpr38”) with overall similarity to human GPR38. The lower part of the figure depicts the structure of the Fndc3a mouse gene, composed of 27 exons distributed over 170 kb (PIP—percent identity plot; Mb—megabase pairs; EST—expressed sequence tag; ORF—open reading frame).

Three conserved sequences were highly similar to exons from GPR38 (Fig. 3). This human gene encodes a member of the G-protein coupled receptor superfamily for which the only known ligand is motilin, a peptide expressed in the gut (McKee et al., 1997; Smith et al., 2001; Tan et al., 1998). Inspection of the sequence of the mouse genome containing the region homologous to human GPR38 revealed multiple independent base substitutions, as well as small deletions and insertions that would preclude the mouse ortholog of GPR38 from encoding a functional mRNA (data not shown). Consistent with this result, BLAST analysis of both the nonredundant and EST mouse databases using the sequence of the mouse genome with similarity to GPR38 coding sequence found no evidence for a transcript from the mouse locus (data not shown).

Genetic complementation analysis indicates that male sterility in sys mice is due to mutation of Fndc3a

The above results suggested that mutation of Fndc3a was the cause of male sterility in sys mice. To test this hypothesis, we performed a genetic complementation analysis using mice with a specific mutation in Fndc3a. The RRP208 ES cell line, identified within the BayGenomics resource, contains a mutant allele of Fndc3a produced by integration of a gene-trap vector within intron 3 of Fndc3a. Integration of the gene-trap vector is predicted to cause loss of full-length FNDC3A and result in production of a fusion product composed of the first 57 amino acids of FNDC3A fused to β-GEO.

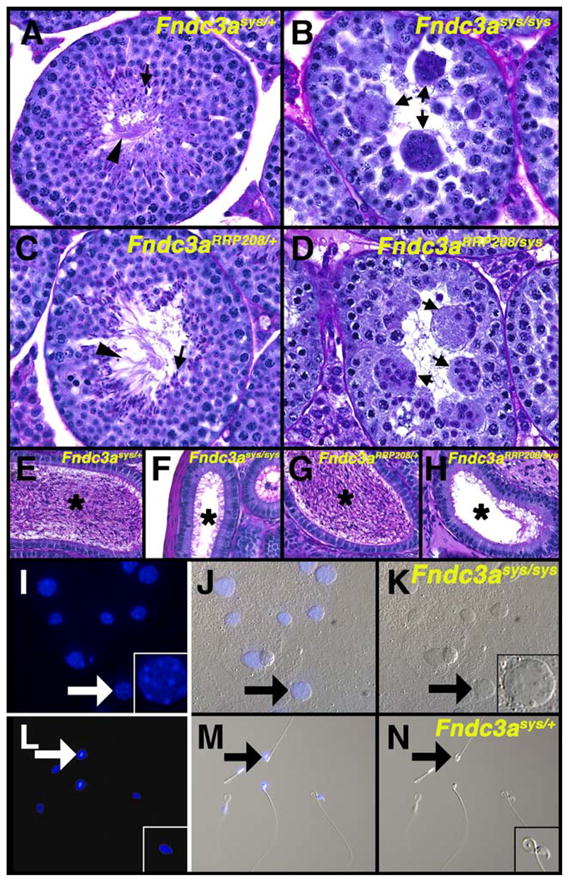

The RRP208 ES cell line was used to generate chimeric mice that were mated with B6 females to generate mice with the mutant allele of Fndc3aRRP208. To perform the complementation test, N2 backcross generation mice on a B6 strain background heterozygous for Fndc3aRRP208 were mated with animals heterozygous for the sys mutant allele of Fndc3a (Fndc3asys). Offspring were screened using PCR to identify males that were compound heterozygous mutant for Fndc3a (i.e. Fndc3asys/Fndc3aRRP208) as well as control animals that were heterozygous for each mutant allele of Fndc3a. At 8 weeks of age, male mice of these genotypes were mated with female B6 mice and animals checked on a daily basis for the presence of copulation plugs, pregnancy, and litter size. Both Fndc3asys/+ and Fndc3aRRP208/+ males were each able to sire offspring. In contrast, as with sys homozygote males, Fndc3asys/Fndc3aRRP208 males were unable to produce offspring, despite being able to inseminate females. We analyzed histology of the epididymides of Fndc3asys/Fndc3aRRP208 and control mice (Fig. 4). Consistent with their inability to sire offspring, the caudal epididymides of Fndc3asys/Fndc3aRRP208 mice were devoid of mature spermatozoa (Fig. 4H) as was also observed in Fndc3sys homozygous males (Fig. 4F). Similarly, the seminiferous epithelium of Fndc3asys/Fndc3aRRP208 mice lacked mature elongate spermatids and contained symplasts of spermatids (Fig. 4D) that were indistinguishable from those observed in the testis of Fndc3sys homozygous mice (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Male sterility in sys mice is due to mutation of Fndc3a. (A) PAS-hematoxylin stained testis histology of an adult Fndc3asys/+ mouse. The seminiferous epithelium has a normal appearance, with heads (arrow) and flagella (arrowhead) of elongate spermatids. (B) Testis histology of Fndc3asys homozygote mouse, with the absence of elongate spermatids and the presence of symplasts of round spermatids (arrows). (C) Testis histology of Fndc3aRRP208/+ adult male mouse, with normal appearance of the seminiferous epithelium. (D) Testis histology of Fndc3aRRP208/Fndc3asys compound heterozygote adult male mouse. The histology is essentially identical to that observed in Fndc3asys homozygotes, having symplasts (arrows) but no elongate spermatids. (E–H) Contents of epididymides of (E) Fndc3asys/+, (F) Fndc3asys homozygote, (G) Fndc3aRRP208/+, and (H) Fndc3aRRP208/Fndc3asys compound heterozygote mice. Mature spermatozoa are present in the lumen (asterisks) of the epididymis in control (E, G) but neither sys homozygous (F) nor Fndc3aRRP208/Fndc3asys compound heterozygous mutant mice (H). (I–N) Analysis of contents of vasa deferentia from homozygous (I–K) and heterozygous (L–N) Fndc3asys mice. (I, L) DAPI staining; (K, N) DIC image; (J, M) merged. Arrows indicate example of a symplast of spermatids (I–K) or a mature spermatozoon (L–N). The contents of the vasa deferentia from homozygous animal contain acellular material in addition to symplasts. Magnification=A–H, L–N 200×; I–N, 100×.

Previous studies revealed that after forming, symplasts of spermatids degenerate in an asynchronous manner and are phagocytized by Sertoli cells (Russell et al., 1991a). Symplasts were not observed in the epididymis (Figs. 4F, H). To determine if any symplasts were released from the testis, we analyzed the contents of the vasa deferentia from homozygous mutant Fndc3asys and control mice. Symplasts of spermatids were observed in material extruded from vasa deferentia from Fndc3asys homozygotes, indicating that at least some symplasts pass through the male reproductive tract following their release (Figs. 4I–K). These samples also contained acellular material. In contrast, normal mature spermatozoa were observed in the samples obtained from control mice (Figs. 4L–N).

Thus, a specific mutation in Fndc3a in trans to the deletion on chromosome 14 from sys mice results in male mice that are infertile and which display an identical testicular phenotype to that observed in sys homozygote mice. This supports the conclusion that mutation of Fndc3a is the cause of male sterility in sys homozygous mice.

Molecular analysis of RRP208 gene-trap derived mutant allele of Fndc3a

The results of the above genetic analysis suggested that the Fndc3aRRP208 gene-trap allele of Fndc3a was null for Fndc3a function. To investigate this, we analyzed Fndc3a-specific RNA produced in testes of wild-type, Fndc3asys and Fndc3a-heterozygous mice (Fig. 5). In theory, integration of the gene-trap vector within intron 3 of Fndc3a should have two effects. First, transcription of RNA should terminate at the SV40 polyadenylation signal in the pGt0lxf vector. Second, the RNA splice donor signal from exon 3 of Fndc3a should be trapped by the efficient RNA splice acceptor signal in the gene trap vector. To test these predictions, we analyzed expression of different regions of the Fndc3a RNA transcript using RT-PCR. As anticipated, a cDNA amplification product composed of the 3′ end of exon 2 fused to β-geo was detected by RT-PCR using total RNA isolated from testis of Fndc3asys/Fndc3aRRP208 mice (Fig. 5B). As predicted, we were unable to detect transcription of exons of Fndc3a located downstream of the gene trap vector in testis RNA from Fndc3asys/Fndc3aRRP208 mice (Fig. 5B), which indicates that the presence of the gene-trap within intron 3 of Fndc3a prevented transcription of exons 3′ to the integration site of the gene-trap vector.

The results of the RT-PCR analysis predict that the Fndc3aRRP208 allele produces a protein containing the first 57 amino acids of FNDC3A fused to β-GEO. To investigate this, we prepared total protein from testes of Fndc3asys/Fndc3aRRP208 and control mice and performed Western analysis using polyclonal antisera generated against aa 137 to 276 of mouse FNDC3A (Fig. 5C). Wild-type mice show six polypeptide species that cross-react specifically with the anti-FNDC3A antisera. The same products are observed in testis from an Fndc3aRRP208/+ mouse. However, none of the six products is detected in protein from testis of Fndc3asys homozygote or Fndc3asys/Fndc3aRRP208 compound heterozygous mutant mice (Fig. 5C). Collectively, the RT-PCR, western, histology, and genetic analyses support the conclusion that the Fndc3aRRP208 allele is null for FNDC3A function and that the mutation of Fndc3a is the cause of the failure of adhesion between spermatids and Sertoli cells observed in sys mice.

Fndc3a is a member of a novel gene family that encode proteins with a proline-rich N-terminus, multiple fibronectin type III domains, and a hydrophobic C-terminus

Fndc3a encodes an 1198 amino acid protein that contains a proline rich region at its amino-terminus, followed by nine fibronectin type-III (FnIII) domains, and a carboxy-terminal hydrophobic sequence (Fig. 5A). While screening the NCBI and Ensembl public genome databases by BLAST analysis using the sequence of the full-length Fndc3a cDNA, we discovered that Fndc3a is a member of a three-gene family in mice. One of these genes, Fad104, was previously identified as one of many genes whose steady-state level of mRNA increased during early stages of differentiation of NIH3T3-L1 pre-adipocyte cells into adipocytes; hence Factor associated with Adipocyte Differentiation (FAD) (Tominaga et al., 2004). As Fad104 is a paralog of Fndc3a, it was renamed Fndc3b by the mammalian genome nomenclature committee. Fndc3b is located on mouse chromosome 3, band A3. Fndc3a is also conserved with sequences on the mouse X-chromosome. To determine whether these X-linked sequences are transcribed in mice, we analyzed the dbEST for sequences that were generated from mouse tissues. Multiple independent ESTs were identified indicating that these sequences are transcribed in several organs in developing mice including brain and placenta (data not shown). We sequenced several independent EST cDNA clones with homology to this X-linked isoform of Fndc3a (data not shown, Fndc3c cDNA sequence is deposited in GenBank, with accession number DQ192038). As with Fndc3a and Fndc3b, the X-linked member of this gene family also has the capacity to encode an amino-terminal proline rich protein, which contains eight FnIII domains, plus a carboxy-terminal hydrophobic sequence. Based on the conservation of this gene with Fndc3a and Fndc3b, it was named Fndc3c by the mammalian genome nomenclature committee.

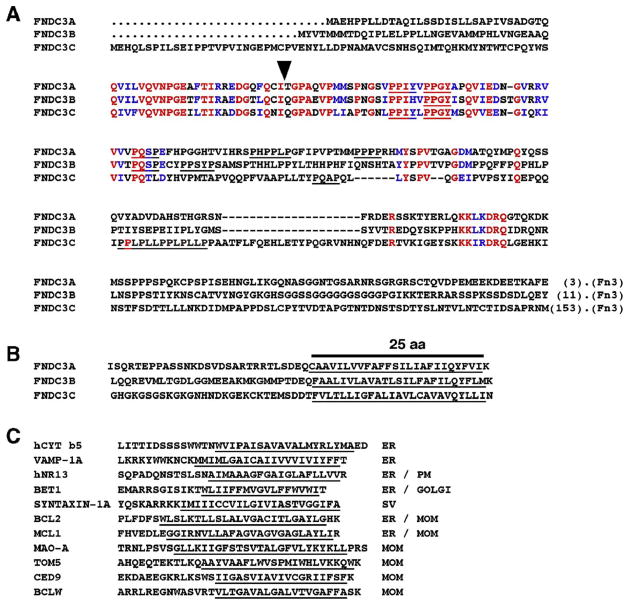

Analysis of peptide sequence of FNDC3A–C

To begin to understand how members of the FNDC3 family function, we compared FNDC3A–C to identify regions of conserved amino acids that could be important for the protein’s function. A pairwise comparison of the primary amino acid sequences of mouse FNDC3A–C revealed that FNDC3A (size 1198 aa, theoretical mass 132 kDa) and B (1207 aa/133 kDa) are 49% identical/66% identical+similar, while the equivalent values for FNDC3A and C (1356 aa/150 kDa) are 38%/52% and FNDC3B and C are 35%/50%. The amino-terminus of each member of the FNDC3 family is proline-rich and contains several canonical binding sites for SH3-domain (PXXP-binding) and type-I WW domain (PPLP, PXXY-binding) containing proteins (Fig. 6A). One PPXY motif (PPGY) is conserved in mouse FNDC3A, B, and C (Fig. 6A). This PPGY motif is within a region of approximately 60 amino acids that has the highest degree of conservation between all family members. All other PXXP or PXXY motifs appear unique to each family member. Orthologs of Fndc3 were identified in additional vertebrates, including X. laevis, X. tropicalis, D. rerio, and O. latipes (data not shown). A single ortholog was also found in the urochordate Ciona intestinalis. In each of these related proteins, the PPGY motif was conserved, suggesting that this motif is of functional importance (data not shown). We also identified an Fndc3 family member Drosophila melanogaster (CG31738) that also encodes a protein composed of a proline rich amino-terminus, nine FnIII domains, and a hydrophobic carboxy-terminus. However, no ortholog of Fndc3 was identified in other invertebrates, including Caenorhabditis and Dictyostelium.

Fig. 6.

Amino acid sequence of FNDC3 family proteins. (A) Alignment of the proline-rich sequence at the amino-terminus of the Mus musculus FNDC3 protein family. Identical amino acids are colored red while those with similarity are blue. There is one region in the amino-terminus that displays relatively high degree of conservation between each family member (red and blue colored residues in the second row). Consensus binding sites for types I WW domains (PPXY) (Sudol, 1996) and SH3 domains (PXXP) are underlined. The sequences shown are from the amino-terminus of each protein to the start of the first fibronectin type III domain (Fn3). The numbers in parentheses at the end of each sequence indicate the amino acids downstream of the sequence before the first fibronectin type-III domain. The arrow indicates the position at which β-GEO is fused to the first 57 amino acids of FNDC3A in the RRP208 mutant allele of Fndc3a. (B) Alignment of multiple amino acid sequences from carboxy-terminus of mouse FNDC3 family proteins. Putative transmembrane domains predicted by Kyte–Doolittle hydropathy plot analysis are underlined. (C) Amino acid sequence of known integral membrane proteins having transmembrane domain at the carboxy-terminus. The subcellular localization of these proteins is indicated; ER—endoplasmic reticulum, PM—plasma membrane, Golgi—Golgi apparatus, MOM—outer membrane of mitochondrion, SV—synaptic vesicle (data from Kaufmann et al., 2003).

The carboxy-terminus of each member of the FNDC3 family contains a region rich in hydrophobic amino acids (Fig. 6B). Analysis by Kyte–Doolittle hydropathy plot suggests that each of these sequences has the capacity to function as an integral membrane protein. Indeed, the carboxy terminus of each of the FNDC3 family members is similar in its overall length and composition of hydrophobic and charged amino acids to those found in the carboxy termini of known so called ‘tail-anchored’ integral membrane proteins, such as BCLW, BCL2, and MCL1 (Fig. 6C) that are anchored to the ER via their carboxy-terminus with their amino terminus projecting into the cytosolic compartment. Analysis of the primary amino acid sequence of each FNDC3 family member using PSORTII and SignalP (neural network) algorithms (http://us.expasy.org/tools/) found no evidence for the presence of a signal peptide at the amino terminus (data not shown). Together, these findings suggest that FNDC3 family members may be integral membrane proteins that are localized to the cytosolic face of intracellular membranes via their carboxy-termini.

FNDC3A is expressed in spermatids and Leydig cells within the adult mouse testis

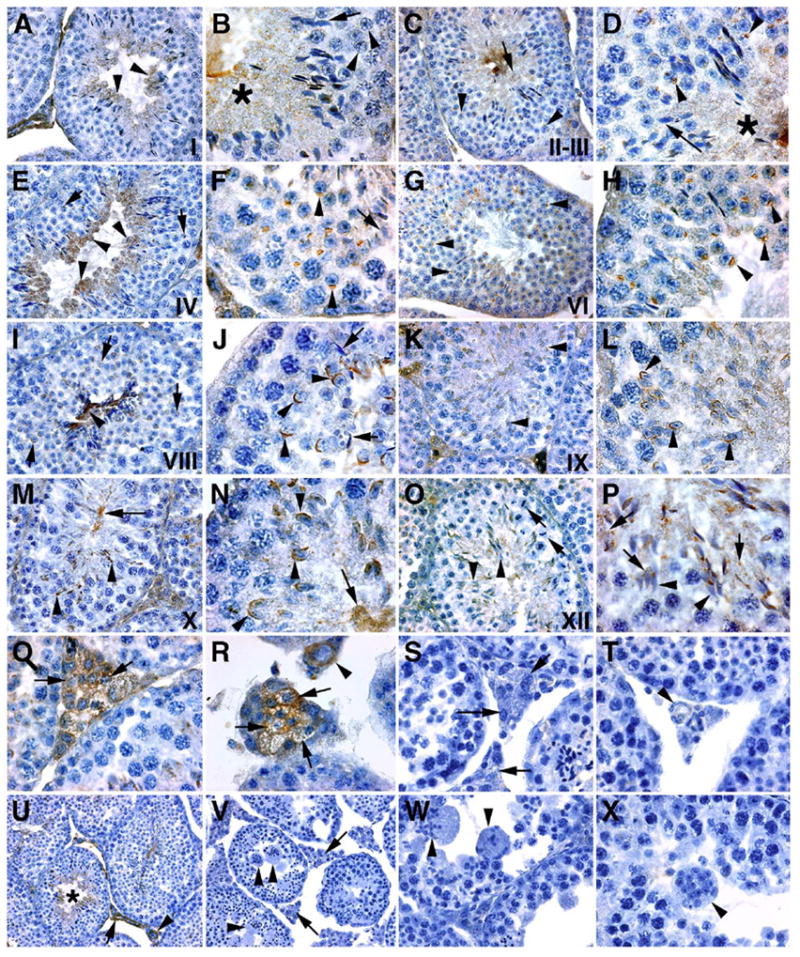

To identify where FNDC3A is expressed within the testis and to identify its subcellular localization, we developed polyclonal antisera using recombinant protein derived from the proline rich region of FNDC3A, and used this to perform immunohisto-chemistry on testis histology from wild-type and sys homozygote mice (Fig. 7). Expression of FNDC3A was observed in spermatids and in Leydig cells. Expression in round spermatids was first observed between stages II and III (Figs. 7C, D). At this stage, FNDC3A was localized to the developing acrosome in step 2–3 spermatids (arrowheads, Fig. 7D) as well as in the caudal cytoplasm of elongate step 14 spermatids (asterisk, Fig. 7D). The same localization was observed in step 4 (round) and early step 15 (elongate) spermatids at stage IVof the cycle (Figs. 7E, F). By stage VIII, acrosomal staining in step 8 spermatids was prominent, while in elongate germ cells staining was restricted to the caudal region of the elongate spermatid (Figs. 7I, J). The acrosomal localization of FNDC3A persisted during spermatid elongation between steps 9 and 10 (Figs. 7K–N). At stage XII, the localization within step 12 spermatids changed, with some immunostaining being localized over the acrosome, while the majority was localized to the cytosol, often appearing as vesicular droplets (Figs. 7O, P). FNDC3Awas also present in Leydig cells (Figs. 7Q, R), with a distribution consistent with localization to the surface of vesicles (Fig. 7R, arrows). Finally, FNDC3A was also present in endothelial cells of blood vessels (Fig. 7R). In histology from sys homozygous mutants prepared and reacted for immunohistochemistry in parallel, only minimal background staining was observed (Figs. 7S, T, V–X).

Fig. 7.

Immunolocalization of FNDC3A to Leydig cells and spermatids. Immunolocalization of FNDC3A in testis of wild-type (A–R, U) and Fndc3asys homozygous (S, T, V–X) mice. (A, B) Seminiferous epithelium at stage I; FNDC3A (brown staining) is observed in the cytoplasm of elongate (A—arrowheads; B—asterisk) but not round (B—arrowheads) spermatids. At this stage, FNDC3A is not present on the dorsal surface of the acrosome in step 13 spermatids (B—arrow). (C, D) Stages II–III; as in stage I, FNDC3A is present in the cytoplasm (D—asterisk), but not localized to the acrosome (D—arrow) of elongate spermatids. No staining is observed in pachytene spermatocytes (C—arrowheads). In step 3 round spermatids, FNDC3A localizes to the acrosomal vesicle (D—arrowheads). (E, F) Stage IV tubules. FNDC3A is cytoplasmic in elongate spermatids (E—arrowheads) and localized to the acrosome in step 4 spermatids (E—arrow, F—arrowheads). Note the absence of FNDC3A localization to the acrosome in elongate spermatids (F—arrow). (G, H) Stage VI tubules. FNDC3A is localized to the acrosome of step 6 spermatids (G, H—arrowheads). The intensity of staining in the cytoplasm of elongate spermatids at stage VI is reduced compared to stage IV. (I, J) Early stage VIII tubules. FNDC3A-immunoreactivity in elongate germ cells is restricted to the flagellar region (I—arrowhead), with no reactivity observed over the acrosome (J—arrows). Immunoreactivity in step 8 round spermatids appears localized to the acrosomal membrane (I, J—arrowheads). (K, L) Stage IX tubules. FNDC3A immunoreactivity localizes to the acrosome of elongating step 9 spermatids (K, L—arrowheads). At step 9 in spermiogenesis, spermatids first display significant punctate immunoreactivity in the cytosol. (M, N) Stage X seminiferous epithelia. As with stage IX, FNDC3A appears localized to the acrosome of elongate spermatids (M, N—arrowheads). Punctate localization of FNDC3A is also apparent within the cytosol of spermatids in the vicinity of developing flagella that project into the lumen of the tubule (M, N—arrow). (O, P) Stage XII tubules. Spermatocytes in meiotic metaphase are observed (O—arrows). In step 12 spermatids, FNDC3A is no longer localized to the acrosome (O, P—arrowheads). A new pattern of subcellular localization is observed in step 12 elongate spermatids, with FNDC3A immunoreactivity having a punctate and sometimes vesicular appearance (P—arrows). (Q, R) Localization of FNDC3A to Leydig cells (Q, R—arrows) and blood vessel endothelial cells (R—arrowhead). (S, T) Negative control for specificity of antisera—immunohistochemistry of testis from Fndc3asys homozygote animals. Organs were fixed, processed, and reacted in parallel to samples from wild-type animals. Only weak background staining is observed in Leydig cells (S—arrows) or endothelial cells of blood vessels (T—arrowhead). (U, V) Low power magnification of staining for FNDC3A in seminiferous epithelium and inter-tubule area in wild-type (U) or Fndc3asys homozygote (V) mice. (U) In wild-type mice, staining is observed in the cytoplasm of elongate spermatids (asterisk), Leydig cells (arrow) and blood vessel endothelial cells (arrowhead). (V) No significant staining is observed in samples from Fndc3asys homozygous mice. Arrowheads indicate symplasts while arrows denote Leydig cells. (W, X) Additional higher magnification view of symplasts of spermatids (arrowheads) in Fndc3asys homozygous mice. Note the absence of any significant immunohistochemical staining. Magnification (U, V—100×; A, C, E, G, I, K, M, O—200×; B, D, F, H, J, L, N, P, Q, R, S, T, W, X—400×).

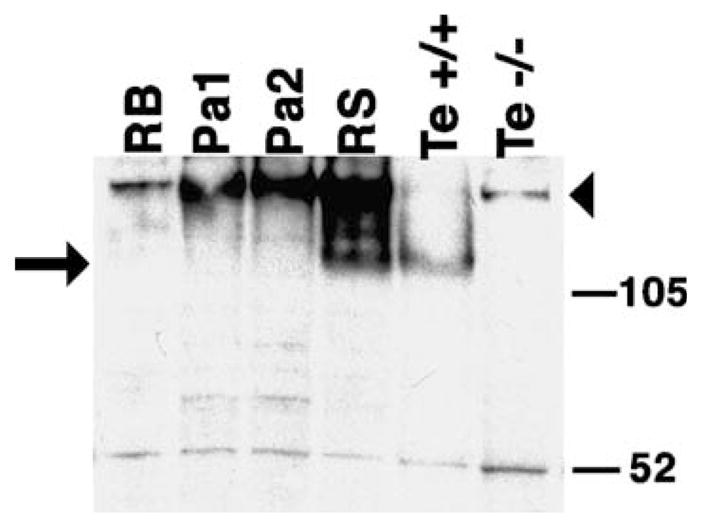

To verify that FNDC3A was expressed in round spermatids, we performed western analysis of extracts from enriched populations of testicular germ cells (Fig. 8). Consistent with immunohistochemical analysis of FNDC3A in testis (Fig. 7), a relatively strong signal for FNDC3A was detected in extracts prepared from enriched populations of spermatids compared to the signal observed in protein from whole testis extract (Fig. 8). The data also confirm that FNDC3A is not present in residual bodies.

Fig. 8.

Western analysis of FNDC3A expression in enriched preparations of germ cells. Total protein extracts (15 μg, except 25 μg sample from homozygous mutant) were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by blotting, and incubated with FNDC3A antisera. Key: RB, Residual bodies; Pa1, low enrichment pachytene spermatocytes; Pa2, highly enriched pachytene spermatocytes; RS, round spermatids; Te +/+, whole testis from wild-type mouse; Te −/−, whole testis from Fndc3asys homozygous mouse. FNDC3A (arrow) is enriched in round spermatids compared to the other germ cell enriched-fractions and whole testis. The nonspecific band at approximately 52 kDa was used to monitor the relative amount of protein loaded per lane. Due to the reduced amount of protein loaded, the relatively high molecular weight band (arrowhead) observed in the testis extract from the homozygous mutant and preparations of enriched germ cells appears faint in the testis extract from the wild-type animal.

Discussion

Sys mice have a deletion of 1.24 Mb of chromosome 14 that generates a null allele of Fndc3a

The sys line of transgenic mice was generated by microinjection of a RSV-lacZ transgene into the pronucleus of a fertilized oocyte (MacGregor et al., 1990). Molecular analysis of transgenic mice generated in this manner indicates that integration of the transgene complex is often accompanied by rearrangement of the genome near the site of integration (Headon and Overbeek, 1999; Mochizuki et al., 1998; Qin et al., 2004; Rijkers et al., 1994; Zhou et al., 1995). A plausible explanation for this outcome involves breakage of the condensed chromatin within the pronucleus during microinjection of the transgene. Double-strand breaks in genomic DNA could become ligated with the injected transgenic DNA, with intervening genomic DNA between the two breaks being removed or transposed to an alternative location. This model offers a simple explanation for the genetic alteration in the sys line of mice with a deletion of 1.24 Mb of chromosome 14. We cannot exclude the possibility that additional deletion(s) occurred during integration of the transgene complex on mouse chromosome 14 in sys mice. However, as the transgene has been backcrossed to C57BL/6 (B6) mice for 12 generations, it is likely that any such unlinked deletion would have been removed. Thus, the gene affected in sys mice was predicted to map within this 1.2 Mb interval of chromosome 14.

Comparative analysis of mouse and human genomes suggests that Fndc3a is the only gene deleted in sys mice

Comparative genomic analysis between the region of mouse chromosome 14 deleted in sys mice and the homologous regions of the human genome (8p21 and 13q12) suggested that Fndc3a is the only actively transcribed gene within this interval. Consistent with this, analysis of the most recent release (v37) of the mouse genome assembly at Ensembl suggests that Fndc3a is the only protein coding gene located within a 2.1 Mb region of mouse chromosome 14. In theory, a requirement for Fndc3a in mouse reproduction would place positive selective pressure on retention of this locus within this relatively gene-sparse region.

Three sequences in the deleted interval in sys mice were similar to exons from GPR38. This human gene encodes a member of the G-protein coupled receptor superfamily (Smith et al., 2001; Tan et al., 1998). The GPR38-related coding sequence in the mouse genome contains several insertions and deletions that appear to preclude synthesis of GPR38 in mice. In humans, the only known ligand for GPR38 is motilin, a growth hormone secretagogue peptide produced within the gut (Smith et al., 2001). Interestingly, the region of the mouse genome with highest identity to the coding sequence in the human motilin gene also contains deletions and insertions similar to those found in the mouse GPR38-related sequences. Thus, as with mouse “Gpr38”, the sequence changes in the mouse “motilin” locus also preclude synthesis of a motilin gene product in mouse. In support of this conclusion, BLAST analysis of the mouse EST database with coding sequences for human GPR38 and Motilin identified no cDNA for either coding sequence (data not shown). Based on these results, we conclude that GPR38 and motilin are extinct genes in mice. Collectively, these results strongly suggested that the male sterility in sys homozygote mice was due to mutation of Fndc3a. Hereafter, we refer to the null mutant allele of Fndc3a in sys mice as Fndc3asys.

Mice with a specific mutation in Fndc3a display male infertility identical to that observed in sys homozygotes

A genetic complementation analysis verified that mutation of Fndc3a is the cause of male infertility in sys homozygote males. The Fndc3aRRP208 mutant allele of Fndc3a encodes a fusion protein composed of the first 57 amino acids of FNDC3A fused to β-geo. This part of FNDC3A contains approximately 20 amino acids of a region that is highly conserved between each of the FNDC3 family members in mice (Fig. 6), which raised the question of whether this mutant allele is null for FNDC3A function. Analysis of Fndc3aRRP208 homozygous mutant males indicates that these animals are also sterile and their testis histology is indistinguishable from that observed in both Fndc3asys homozygous and Fndc3asys/Fndc3aRRP208 compound heterozygous mice (data not shown). Thus, from a genetic and histological perspective, the RRP208 mutant allele of Fndc3a is null for Fndc3a function. This is consistent with the results of RT-PCR and western analysis, which indicate that any full-length mRNA or protein for FNDC3A in testis of compound heterozygous mutant Fndc3asys/Fndc3aRRP208 mice is below the level of detection offered by these assays.

FNDC3A is a member of a family of novel putative membrane-anchored proteins that contain a proline-rich amino terminus and multiple FnIII domains

A BLAST analysis of the coding sequence for Fndc3a against the Ensembl mouse genome database revealed the existence of two loci that encode proteins closely related to FNDC3A, namely Fndc3b (previously known as Fad104, for factor for adipocyte differentiation-104 (Tominaga et al., 2004)) on chromosome 3, and Fndc3c on the X-chromosome (data not shown). The amino terminus of FNDC3A contains several canonical binding sites for type I WW domain containing proteins. WW domains are named for the pair of tryptophan (W) residues that contained approximately 20 residues apart in their 30 amino-acid sequence (Ilsley et al., 2002; Sudol, 1996). WW domain containing proteins are involved in a variety of biological processes, including DNA transcription, viral budding, and muscle function (Ilsley et al., 2002), and have been classified in four categories based on their ligand specificity. The binding sites in FNDC3 family members are those optimal for type I (PPxY binding site) and type II (PPLP binding site) WW domain containing proteins. One such sequence (PPGY) is conserved in each of the mouse paralogs as well as all known orthologs of FNDC3 proteins. Interestingly, this motif is located within an approximately 60 amino acid region of the amino terminus that is highly conserved in FNDC3 paralogs in mice, as well as in orthologs in other species (data not shown), raising the possibility that protein–protein interactions may occur within this region. Additional canonical WW domain binding sites are found in the individual family members, but most of these are unique to each family member. It is possible that the unique WW domain ligand, or other (e.g. PXXP SH3-domain ligand; Jia et al., 2005) sites that are also present in FNDC3A could confer specificity with respect to proteins with which the different family members interact.

FNDC3A contains nine fibronectin type III (FnIII) domains. These domains are found in approximately 2% of mammalian proteins and have sequence homology with a module that is repeated 15 times in the extra-cellular matrix protein fibronectin (Craig et al., 2004; Pankov and Yamada, 2002). The tenth FnIII domain in fibronectin contains an RGD-amino acid sequence to which cell binding can occur via the extra-cellular domain of transmembrane-linked integrins (Pankov and Yamada, 2002). In contrast, none of the FnIII domains in FNDC3A contains an RGD sequence, which makes it unlikely that it could mediate adhesion to integrins. Moreover, none of the FNDC3 proteins has a signal peptide at its amino-terminus that could direct the protein to the secretory pathway, which would be required if the protein was to bind to the extra-cellular domain of an integrin subunit. BLAST analysis indicates that the FnIII domains in the FNDC3 proteins are most closely related to those found in titin, an intracellular protein that is a component of the cytoskeleton in muscle cells (Tskhovrebova and Trinick, 2003, 2004). Based on this evidence, we propose that the FNDC3 family members are membrane-anchored cytosolic proteins that associate with proteins via their proline-rich amino-terminus, with the FnIII domains functioning possibly as spacer modules.

We noticed a similarity between the carboxy-termini of FNDC3 family members and those of other proteins (Fig. 6), including BCLW, BCL2 and MCL1, members of the death-protecting branch of the BCL2 family of apoptosis regulators (Kaufmann et al., 2003). This sequence is required to localize these proteins as carboxy-terminal ‘tail-anchored’ (TA) (Borgese et al., 2003) integral membrane proteins to the cytosolic face of the ER and mitochondria (Wilson-Annan et al., 2003). The relatively long hydrophobic and basic sequence found at the carboxy-terminus of FNDC3A may also confer upon it properties of a TA protein; i.e. an integral membrane protein localized to the ER, or compartments derived thereof, via its hydrophobic and charged carboxy-terminus, with its amino-terminus projecting into the cytosolic compartment.

Fndc3a is expressed in spermatids, where it is localized to the acrosome, and Leydig cells

Previous studies involving analysis of chimeric mice generated by aggregation of wild-type and homozygous mutant sys embryos suggested that the gene whose mutation generates the male infertility in sys mice is normally required within a cell type(s) in the testis (MacGregor, 2002). The data presented here support and extend this conclusion indicating that this gene is Fndc3a and that the cell type is most likely either Leydig cells, spermatids, or possibly both cell types.

During spermatogenesis, FNDC3A is first detected in germ cells at the round spermatid stage where it is localized to the developing acrosome. Although the membrane topology of FNDC3A is currently unknown, the absence of a recognizable signal peptide sequence at the amino terminus (or anywhere else within FNDC3A), plus the hydrophobic domain at the extreme carboxy-terminus suggests that FNDC3A may function as an integral membrane protein, inserted within the cytosolic leaflet of the acrosomal membrane, with the amino terminus of the protein projecting into the cytosolic compartment. Studies are underway to test this model.

FNDC3A can be detected on the acrosome beginning at steps 2–3 and continuing until step 12 of spermiogenesis at which time it appears predominantly as ‘droplets’ within the cytosol. Localization of FNDC3A to the acrosome during step 8 indicates that it could function in this location to mediate adhesion between spermatids and Sertoli cells. In contrast, the absence of FNDC3A from the acrosome during late stages of spermiogenesis suggests that continued acrosomal location is unnecessary for maintenance of the ectoplasmic specialization (ES) prior to its conversion into the tubulobulbar complex (Guttman et al., 2004; Russell and Clermont, 1976; Tanii et al., 1999), a specialized anchoring complex that substitutes for the ES in mediating spermatid–Sertoli adhesion prior to release of mature elongate spermatids at spermiation.

FNDC3A was also detected in Leydig cells. At the light microscopic level, FNDC3A appeared to be distributed in an uneven manner within this cell type (e.g. Figs. 6Q, R). Leydig cells contain relatively large amount of smooth ER, which together with mitochondria, serve as sites for location of different enzymes required for synthesis of steroids (Payne et al., 1996). Future studies will attempt to use immuno-EM to investigate the subcellular localization of FNDC3A within Leydig cells as well as spermatids.

Possible mechanisms for FNDC3A function in spermatogenesis

Our results indicate that Fndc3a is required for spermatogenesis in mice and that it most likely functions in spermatids or Leydig cells, or possibly both cell types, to maintain adhesion between spermatids and Sertoli cells. During spermiogenesis, haploid germ cells maintain adhesion with Sertoli cells via different forms of adhesion junctions (Mruk and Cheng, 2004b). In mice, during the round spermatid stage of development (steps 1–8), spermatids are attached to Sertoli cells via both adherens and desmosome-class junctions. However, from step 8 onwards, these complexes are replaced by a specialized adhesion structure; the ES (Mruk and Cheng, 2004b; Russell, 1977). As ES also exist between Sertoli cells in the basal part of the seminiferous epithelium, the spermatid–Sertoli ES is referred to as the apical ES. Formation of the apical ES at step 8 of mouse spermiogenesis involves apposition of the outer membrane of the acrosome, the plasma membrane of the spermatid head where it overlaps the acrosome, and the plasma membrane of the Sertoli cell (Fig. 9) (Mruk and Cheng, 2004b; Russell, 1977). The Sertoli cell side of the apical ES consists of multiple bundles of hexagonally arranged filamentous actin sandwiched between the Sertoli cell plasma membrane and a small area of smooth ER (Fig. 9). Current models predict that the actin bundles provide localized structural rigidity to the ES as well as serving as a site for assembly of Sertoli cell cytosolic and transmembrane proteins required for adhesion between Sertoli cells and spermatids (Mruk and Cheng, 2004b; Vogl et al., 2000). Components localized on the spermatid side of the ES that may be involved in maintenance of the ES include laminin, nectin, and cadherin as well as members of the c-src family of nonreceptor tyrosine kinases (Mruk and Cheng, 2004a; Siu et al., 2005; Vogl et al., 2000), although little is known about how these molecules are localized to the ES.

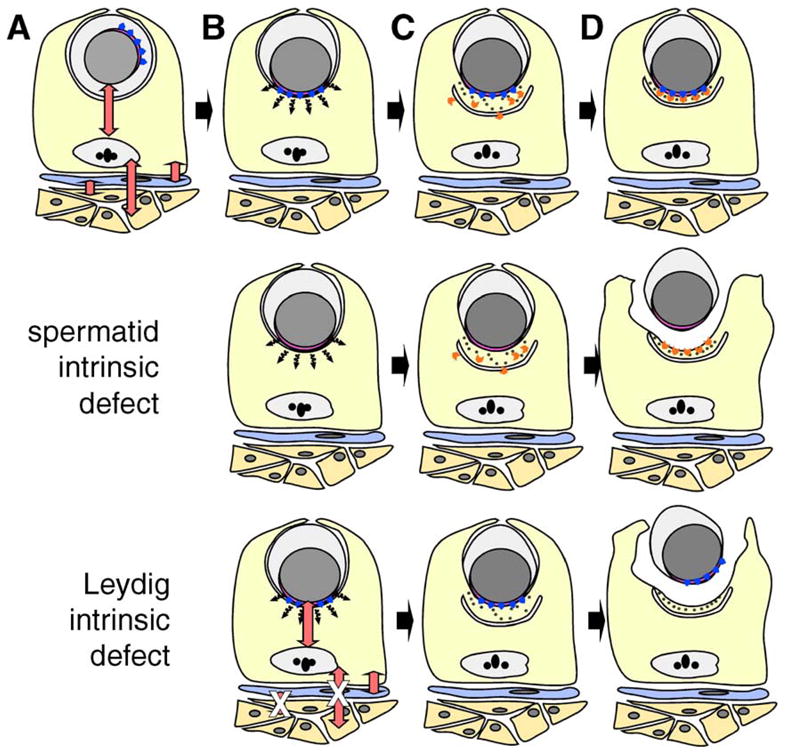

Fig. 9.

Models to explain the underlying defect in spermatid–Sertoli adhesion in FNDC3A-deficient mice. (A–D) Formation of the ES adhesion junction in wild-type mice. Depicted are Leydig cells (orange), peritubular myoid cell (blue), Sertoli cell (yellow), and a round spermatid. For clarity, other types of germ cells and interstitial cells have been omitted. The red double-headed arrows represent communication between somatic and germ cells within the testis (Mruk and Cheng, 2004b; Saunders, 2003; Skinner, 1991). (A) A round spermatid at step 7 of spermiogenesis. The nucleus (grey) and its tightly apposed acrosome (pink) are located centrally within the round spermatid. The Golgi apparatus is usually located in proximity to the acrosome, which is randomly orientation relative to the basal compartment of the seminiferous epithelium. The blue arrowheads represent proteins localized to the cytosolic face of the acrosome, which are directly or indirectly required within spermatids to form a functional ES with the Sertoli cell. (B) Round spermatid at step 8. The spermatid nucleus with overlying acrosome has moved to abut the plasma membrane. A hypothetical short-range signal (black wavy arrows) transduced from the vicinity of the acrosome instructs the Sertoli cell to (C) assemble components of the ES on the Sertoli side of the ES. Components of the ES within the Sertoli cells are simplified and show the cisternum of ER (the U-shaped structure), hexagonal bundles of filamentous actin (black dots), and other components of the ES required for formation of the adhesive junction (orange chevrons). (D) Completed assembly of the ES between the step 8 spermatid and Sertoli cell. The cartoon depicts the fact that the lateral boundaries of the ES in the Sertoli cell are defined by the lateral boundary of the acrosome in the spermatid. “Spermatid intrinsic defect,” the second row of the figure depicts a model where defective Sertoli–spermatid adhesion results from loss of FNDC3A function within spermatids. The hypothetical signal is transduced from spermatid to Sertoli cell and components of the ES assemble within the Sertoli cell in a location overlying the acrosome. However, as a consequence of loss of FNDC3Awithin spermatids, the germ cell is unable to adhere to the Sertoli cell. In this scenario, FNDC3A could be a structural component required at the acrosomal membrane for function of cell-adhesion molecules associated with the overlying plasma membrane of the spermatid. “Leydig intrinsic defect,” the bottom row depicts a model where defective Sertoli-spermatid adhesion results from loss of FNDC3A function within Leydig cells. In this case, loss of FNDC3A (depicted by white “X” over red double-headed arrows) perturbs Leydig cell function required to generate a functional ES within the Sertoli cell. Abnormal Leydig cell function could affect Sertoli cells directly, or indirectly e.g. via lymphatic endothelial or peritubular myoid cells.

The length of time required for spermatogenesis in the rat is greater than that required in mice. Results of experiments involving transplantation of rat spermatogonia into mouse testis demonstrated that timing of germ cell development in xenografted animals is germ cell intrinsic (Franca et al., 1998). This indicates that developing germ cells instruct the Sertoli cell to provide local nutritional and structural support required at different stages during germ cell development. As part of this process involves formation of an apical ES at a specific stage during spermiogenesis, it is plausible that the spermatid instructs the Sertoli cell to assemble an ES. In wild-type animals, the ES forms in a location juxtaposed to the acrosome (Russell, 1977; Russell and Griswold, 1993). In mutants where the acrosome does not form properly, or it is separated from the spermatid nucleus, ES-structures within adjacent Sertoli cells form in a location overlying the acrosomal-like structures (Ito et al., 2004; Kang-Decker et al., 2001). Together, these facts suggest a model (Fig. 9) where following movement of the spermatid nucleus and its overlying acrosome to the plasma membrane of the spermatid, an acrosomal-localized signal instructs the underlying Sertoli cell to assemble the components of the ES in this location.

In sys mutant males, loss of adhesion between spermatids and Sertoli cells occurs at step 8, when the ES becomes the sole remaining adhesive junction between these cells types (Mruk and Cheng, 2004b; Russell, 1977). The defective adhesion is associated with opening of cytoplasmic bridges that normally form connecting structures between adjacent spermatid nuclei. This results in formation of spherical symplasts of spermatids. The symplasts subsequently degenerate and are either phagocytized by Sertoli cells (Russell et al., 1991a) or pass through the reproductive tract to the vas deferens. In sys mutants, spermatid nuclei with overlying acrosomes can be observed abutting the plasma membrane of the symplast, which is in contact with a Sertoli cell (Russell et al., 1991b). Electron microscopy analysis of the ES in sys mutants reveals a grossly normal appearance of the cisternum of ER and the associated actin bundles (Russell et al., 1991a,b) suggesting that the Sertoli cell in sys mutants can receive a signal instructing it to form an ES. However, the subsequent loss of adhesion indicates that either the Sertoli cell or the spermatid cannot adhere at the apical ES. Thus, one possibility is that FNDC3A functions in the spermatid to localize, or mediate modification of, molecules required for adhesion to the Sertoli cell at the apical ES (Fig. 9).

Alternatively, FNDC3A might be required in Leydig cells for spermatogenesis, although a model for the function for FNDC3A in Leydig cells in mediating Spermatid–Sertoli adhesion is not immediately apparent. One of the most important functions of Leydig cells is in production of testosterone required to support spermatogenesis. Suppression of testosterone synthesis in the rat leads to loss of adhesion between spermatids and Sertoli cells although the phenotype does not resemble that observed in Fndc3a-mutant mice (O’Donnell et al., 1996, 2000). Moreover, there is no difference in the weight of seminal vesicles, which is androgen-dependent, between sys mutant and control mice nor is there any evidence of Leydig cell hyperplasia in sys mutants which suggests that testosterone production is normal in Fndc3a-mutant mice (MacGregor et al., 1990; Russell et al., 1991a). An alternative possibility is that Fndc3a-deficient Leydig cells are defective in mediating production of a factor(s) that functions in lymphatic endothelial, peritubular myoid, or Sertoli cells to mediate adhesion of Sertoli cells to spermatids. In support of this possibility, adult female Fndc3a-homozygous mutant mice post-partum have a defect in secretion of lipid-containing vesicles from mammary epithelial cells (unpublished results). We are currently analyzing this phenotype as well as analyzing mice deficient for FNDC3B with the rationale that finding a common function for these proteins in somatic tissues will in turn provide insight into the mechanism of action of FNDC3A during spermatogenesis.

In summary, mutation of Fndc3a is responsible for the recessive male sterility in sys mice. Fndc3a encodes a novel protein that is localized to the acrosome in spermatids as well as being expressed in Leydig cells. Analysis of the peptide sequence of FNDC3A suggests a model where FNDC3A is anchored by its carboxy-terminus to the outer leaflet of the acrosome with the amino terminus of the protein projecting into the cytosol, although this remains to be determined experimentally. Based on similar sequences in other proteins, the proline-rich amino-terminus of FNDC3A may interact with currently unidentified proteins to mediate adhesion of spermatids to Sertoli cells at the ES. It remains to be determined whether FNDC3A is required within spermatids, Leydig cells, or possibly both cell types to mediate adhesion between Sertoli cells and round spermatids. Experimental strategies using cell-specific mutation (or rescue) of Fndc3a in mice as well as transplantation of FNDC3A deficient germ cells into wild-type testis and vice versa will be used to resolve this issue.

Acknowledgments

We thank Paul Overbeek for the gift of sys mice, Minoru Ko for cDNA clones, and Darren Gilmour and Steve L’Hernault for stimulating discussions. We thank the UCI Transgenic Mouse Facility for production of transgenic animals. The BayGenomics Mutant ES Cell Resource is supported by NHLBI, NIH, while the MMRRC is supported by NIH/NCRR. This work was supported by U01 HD045913 cooperative agreement from the NICHD, NIH to GRM.

Footnotes

References

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Wiley Interscience; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bellve AR. Purification, culture, and fractionation of spermatogenic cells. Methods Enzymol. 1993;225:84–113. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)25009-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgese N, Colombo S, Pedrazzini E. The tale of tail-anchored proteins: coming from the cytosol and looking for a membrane. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:1013–1019. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun RE, Behringer RR, Peschon JJ, Brinster RL, Palmiter RD. Genetically haploid spermatids are phenotypically diploid. Nature. 1989;337:373–376. doi: 10.1038/337373a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell P, Waymire K, Heier R, Sharer C, Day D, Reimann H, Jaje J, Friedrich G, Burmeister M, Bartness T, Russell L, Young L, Zimmer M, Jenne D, MacGregor G. Mutation of a novel gene results in abnormal development of spermatid flagella, loss of intermale aggression and reduced body fat in mice. Genetics. 2002;162:307–320. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.1.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper GM, Sidow A. Genomic regulatory regions: insights from comparative sequence analysis. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2003;13:604–610. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig D, Gao M, Schulten K, Vogel V. Tuning the mechanical stability of fibronectin type III modules through sequence variations. Structure (Camb) 2004;12:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2003.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kretser D, Kerr J. The cytology of the testis. In: Knobil E, Neill J, editors. The Physiology of Reproduction. Vol. 1. Raven Press; New York: 1988. pp. 837–932. [Google Scholar]

- Franca LR, Ogawa T, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL, Russell LD. Germ cell genotype controls cell cycle during spermatogenesis in the rat. Biol Reprod. 1998;59:1371–1377. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod59.6.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman JA, Takai Y, Vogl AW. Evidence that tubulobulbar complexes in the seminiferous epithelium are involved with internalization of adhesion junctions. Biol Reprod. 2004;71:548–559. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.028803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamer G, Roepers-Gajadien HL, Gademan IS, Kal HB, De Rooij DG. Intercellular bridges and apoptosis in clones of male germ cells. Int J Androl. 2003;26:348–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2003.00436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headon DJ, Overbeek PA. Involvement of a novel Tnf receptor homologue in hair follicle induction. Nat Genet. 1999;22:370–374. doi: 10.1038/11943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilsley JL, Sudol M, Winder SJ. The WW domain: linking cell signalling to the membrane cytoskeleton. Cell Signal. 2002;14:183–189. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito C, Suzuki-Toyota F, Maekawa M, Toyama Y, Yao R, Noda T, Toshimori K. Failure to assemble the peri-nuclear structures in GOPC deficient spermatids as found in round-headed spermatozoa. Arch Histol Cytol. 2004;67:349–360. doi: 10.1679/aohc.67.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia CY, Nie J, Wu C, Li C, Li SS. Novel Src homology 3 domain-binding motifs identified from proteomic screen of a Pro-rich region. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:1155–1166. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500108-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang-Decker N, Mantchev GT, Juneja SC, McNiven MA, van Deursen JM. Lack of acrosome formation in Hrb-deficient mice. Science. 2001;294:1531–1533. doi: 10.1126/science.1063665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann T, Schlipf S, Sanz J, Neubert K, Stein R, Borner C. Characterization of the signal that directs Bcl-x(L), but not Bcl-2, to the mitochondrial outer membrane. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:53–64. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200210084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor GR. An extreme bias in the germ line of XY C57BL/6<–>XY FVB/N chimaeric mice. Reproduction. 2002;124:377–386. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1240377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor GR, Overbeek PA. Use of a simplified single-site PCR to facilitate cloning of genomic DNA sequences flanking a transgene integration site. PCR Methods Appl. 1991;1:129–135. doi: 10.1101/gr.1.2.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor GR, Russell LD, Van Beek ME, Hanten GR, Kovac MJ, Kozak CA, Meistrich ML, Overbeek PA. Symplastic spermatids (sys): a recessive insertional mutation in mice causing a defect in spermatogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:5016–5020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.13.5016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor GR, Zambrowicz BP, Soriano P. Tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase is expressed in both embryonic and extraembryonic lineages during mouse embryogenesis but is not required for migration of primordial germ cells. Development. 1995;121:1487–1496. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.5.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee KK, Tan CP, Palyha OC, Liu J, Feighner SD, Hreniuk DL, Smith RG, Howard AD, Van der Ploeg LH. Cloning and characterization of two human G protein-coupled receptor genes (GPR38 and GPR39) related to the growth hormone secretagogue and neurotensin receptors. Genomics. 1997;46:426–434. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.5069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisler MH. Insertional mutation of ‘classical’ and novel genes in transgenic mice. Trends Genet. 1992;8:341–344. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(92)90278-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochizuki T, Saijoh Y, Tsuchiya K, Shirayoshi Y, Takai S, Taya C, Yonekawa H, Yamada K, Nihei H, Nakatsuji N, Overbeek PA, Hamada H, Yokoyama T. Cloning of inv, a gene that controls left/right asymmetry and kidney development. Nature. 1998;395:177–181. doi: 10.1038/26006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mruk DD, Cheng CY. Cell–cell interactions at the ectoplasmic specialization in the testis. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2004a;15:439–447. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mruk DD, Cheng CY. Sertoli–Sertoli and Sertoli–germ cell interactions and their significance in germ cell movement in the seminiferous epithelium during spermatogenesis. Endocr Rev. 2004b;25:747–806. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell L, McLachlan RI, Wreford NG, de Kretser DM, Robertson DM. Testosterone withdrawal promotes stage-specific detachment of round spermatids from the rat seminiferous epithelium. Biol Reprod. 1996;55:895–901. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod55.4.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]