Abstract

A sudden increase in permeability of the inner mitochondrial membrane, the so-called mitochondrial permeability transition, is a common feature of apoptosis and is mediated by the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mtPTP). It is thought that the mtPTP is a protein complex formed by the voltage-dependent anion channel, members of the pro- and anti-apoptotic BAX-BCL2 protein family, cyclophilin D, and the adenine nucleotide (ADP/ATP) translocators (ANTs)1,2. The latter exchange mitochondrial ATP for cytosolic ADP and have been implicated in cell death. To investigate the role of the ANTs in the mtPTP, we genetically inactivated the two isoforms of ANT3–5 in mouse liver and analysed mtPTP activation in isolated mitochondria and the induction of cell death in hepatocytes. Mitochondria lacking ANT could still be induced to undergo permeability transition, resulting in release of cytochrome c. However, more Ca2+ than usual was required to activate the mtPTP, and the pore could no longer be regulated by ANT ligands. Moreover, hepatocytes without ANT remained competent to respond to various initiators of cell death. Therefore, ANTs are non-essential structural components of the mtPTP, although they do contribute to its regulation.

To investigate the role of ANTs in the mtPTP, we inactivated both the heart-muscle (Ant1) and the systemic (Ant2) ANT isoform genes in the mouse liver. Humans have three ANT genes6,7, whereas results of complementary DNA library screening5 and northern and western analyses3 have suggested that mouse has only two Ant genes. To verify this, we screened the Celera and Ensembl mouse genome assemblies, as well as the respective EST databases, by BLAST analysis using the ANT3 cDNA sequence. Consistent with previous results, this produced only two significant matches; that is, Ant1 and Ant2.

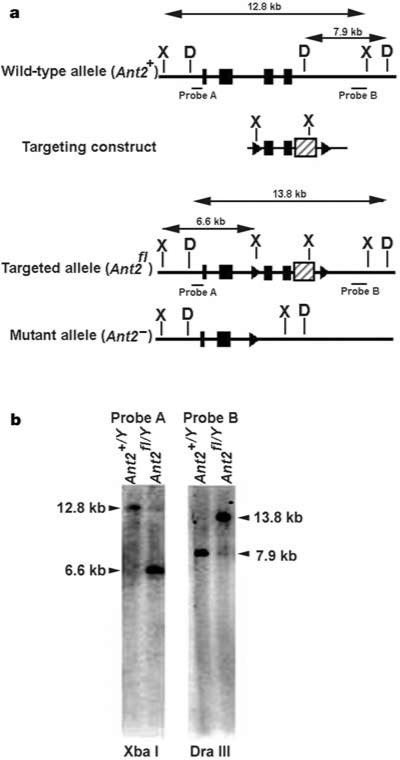

Mice with mutations in Ant1 and Ant2 were generated by homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells. Mice with a non-conditional null mutant allele of Ant1 have been described5. A CRE-conditional null mutant allele of the X-linked Ant2 (Ant2fl) was produced by generating a targeting vector in which loxP sites flanked exons 3 and 4 (Fig. 1a). Targeted embryonic stem cells (Fig. 1b) were used to introduce the conditional floxed allele into the mouse germ line. Liver-specific inactivation of the Ant2fl allele was achieved by breeding Ant2fl mice with an Alb-Cre line of transgenic mice that expresses CRE under control of the liver-specific albumin promoter, which results in the excision of exons 3 and 4 of Ant2 (Fig. 1a). More than 99% of floxed loci are excised in developing hepatocytes of Alb-Cre mice8. The Ant2fl allele was then bred onto an Ant1–/– background5. The resulting Ant1–/–, Ant2fl/fl females were crossed with Ant1–/–, Ant2+/Y, Alb-Cre hemizygous males. Male Ant1–/–, Ant2fl/Y, Alb-Cre progeny, which are null for both Ant1 and Ant2 in their livers, were used to analyse liver mtPTP function. ANT1 is barely detectable in liver3, and Ant1+/+, Ant2fl/Y, Alb-Cre animals gave the same results as Ant1–/–, Ant2fl/Y, Alb-Cre mice (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Preparation of a CRE-conditional Ant2-null mutant allele in mouse embryonic stem cells. a, Top to bottom, maps of the wild-type Ant2 locus, the region of homology within the targeting construct, and the floxed (Ant2fl) and mutant (Ant2–) alleles. Exons (black boxes), loxP sites flanking exons 3 and 4 (triangles), PGKneo selection cassette within 3′UTR (hatched box). a, b, Arrows indicate sizes of Xba I (X) and Dra III (D) restriction fragments used to identify correctly targeted clones by Southern analysis of embryonic-stem-cell genomic DNA using probes A and B. b, Southern blot of targeted and untargeted embryonic-stem-cell clones.

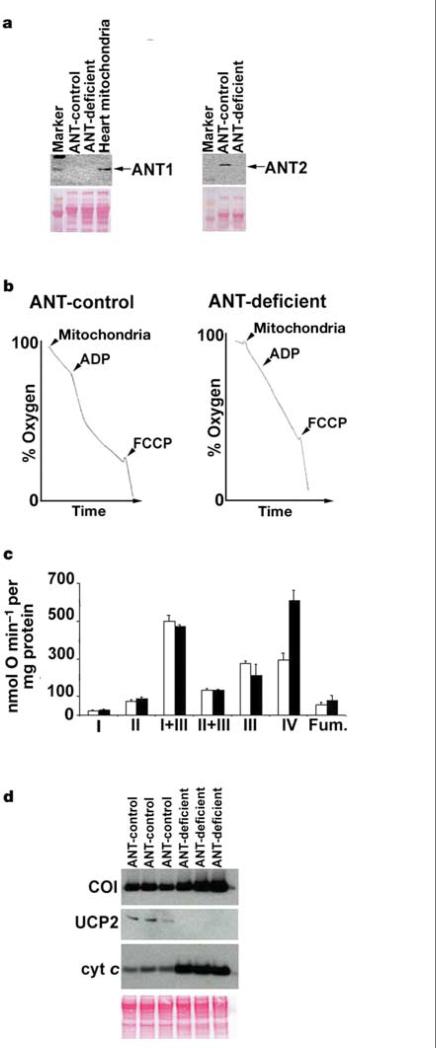

The absence of ANT1 and ANT2 protein in liver mitochondria from Ant1–/–, Ant2fl/Y, Alb-Cre mice was verified by western blot analysis using isoform-specific antibodies (Fig. 2a). Complete ANT deficiency was confirmed by demonstrating that respiration in mitochondria from Ant1–/–, Ant2fl/Y, Alb-Cre animals could not be stimulated by the addition of ADP (Fig. 2b). Hence, the liver mitochondria of the Ant1–/–, Ant2fl/Y, Alb-Cre mice have no ANT.

Figure 2.

Inactivation of ANT in liver mitochondria. a, Western blots of mitochondria using ANT1 and ANT2-specific antibodies. Heart mitochondria are a positive ANT1 control. ANT1 and ANT2 are both 30 kDa (arrows). The Ponceau-S-stained blot (below) is the loading control. b, ADP-stimulated mitochondrial respiration. Arrowheads denote addition of 600 μg of mitochondrial protein, 125 nmol of ADP and 75 nM FCCP. c, OXPHOS enzyme activities of ANT-control (white bars) or ANT-deficient (black bars) liver mitochondria (mean of three mice each). OXPHOS complexes I–IV and fumarase (Fum.) are shown. Error bars show the standard error. d, Western blots of mitochondria from three independent mice for COI (56 kDa), UCP2 (33 kDa), cytochrome (cyt) c (11 kDa). The Ponceau S blot (below) is the loading control.

Endogenous respiration rates of ANT1/ANT2-deficient mitochondria were almost twice that of control mitochondria (34.58 ± 1.6 versus 18.12 ± 1.1 nmol O min–1 per mg protein) (Fig. 2b) and the mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔP = ΔΨ + ΔpH) of the ANT-deficient mitochondria was higher than that of controls (191.7 ± 4.9 versus 172.9 ± 3.5 mV). Analysis of the specific activity of OXPHOS enzyme complexes in ANT-deficient mitochondria revealed that complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase, COX) was increased more than twofold compared with controls (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2c). This was confirmed by western blot analysis, which revealed that the mitochondrial COX subunit I (COI) and cytochrome c proteins were more abundant in the ANT-deficient mitochondria (Fig. 2d). Hence, the increased respiration rate is likely to be the result of the specific upregulation in COX activity, suggesting that COX activity may modulate respiration rate. Because ΔP is the product of proton pumping versus proton leak9, we analysed the level of the systemic uncoupler protein, UCP2, by western blot. UCP2 was downregulated to undetectable levels in the ANT-deficient mitochondria, suggesting that the increased ΔP resulted from decreased proton leak (Fig. 2d).

We then used the ANT-deficient liver mitochondria to investigate the role of ANT in the structure and regulation of the mtPTP. To determine whether the mtPTP was present in the absence of ANT, we isolated mitochondria from livers of ANT-deficient (Ant1–/–, Ant2fl/Y, Alb-Cre) and ANT-control (Ant1–/–, Ant2fl/Y) mice and tested their sensitivity to various inducers of the mtPTP.

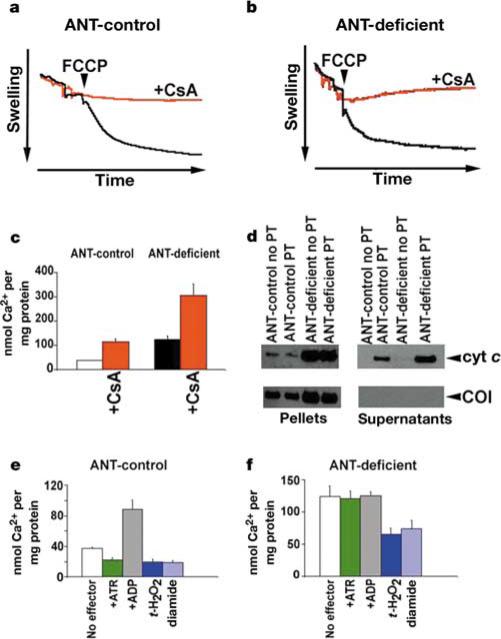

Because the mtPTP is a voltage-dependent channel, we determined whether the mtPTP could be activated by the uncoupler carbonyl cyanide p-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (FCCP) in the presence of Ca2+ (refs 10, 11) (Fig. 3a, b). Opening of the pore was monitored by mitochondrial swelling through decreased light scattering. Strikingly, ANT-deficient and ANT-control mitochondria responded equally well to FCCP-induced mtPTP activation. To confirm that the mitochondrial swelling was due to the activation of the mtPTP, the experiment was repeated in the presence of the mtPTP inhibitor cyclosporin A (CsA). This prevented the swelling of both the ANT-control and ANT-deficient mitochondria (Fig. 3a, b). Hence, the ANT-deficient mitochondria have a functional, CsA-inhibitable mtPTP, demonstrating that ANT is not required to form a functional mtPTP.

Figure 3.

Effect of ANT-deficiency on mtPTP activation in liver mitochondria. a, ANT-control and b, ANT-deficient mtPTP activation by ΔP depolarization (FCCP) monitored by mitochondrial swelling. Black trace, no CsA; red trace, with CsA. c, Amount of Ca2+ required per mg of mitochondrial protein to activate the mtPTP and collapse ΔP. d, Western blots of cytochrome c released into the supernatant fraction versus COI retained in the mitochondrial pellet following Ca2+-activation of the mtPTP. e, ANT-control and f, ANT-deficient Ca2+-activation of the mtPTP in the presence of positive and negative effectors.

To further characterize the mtPTP in ANT-deficient mitochondria, we quantified the propensity of ANT-deficient and ANT-control mitochondria to undergo the permeability transition by determining the concentration of Ca2+ required to activate the mtPTP and collapse ΔP. Mitochondria were energized with succinate in the presence of the lipophilic cation tetraphenylphosphonium cation (TPP+). TPP+ is accumulated into the mitochondrial matrix in proportion to ΔP, and its concentration in the suspension medium can be monitored using a TPP+-sensitive electrode12,13. Aliquots of Ca2+ were added to the reaction, each addition causing a transient release of TPP+ as Ca2+ was taken into the mitochondria at the expense of ΔP. The Ca2+ additions were repeated until sufficient Ca2+ accumulated in the mitochondrial matrix to activate the mtPTP, collapsing ΔP and irreversibly releasing the mitochondrial TPP+. This process can be inhibited by CsA. Hence, the amount of Ca2+ required to cause TPP+ release provides a quantitative measurement of the sensitivity of the mtPTP.

ANT-deficient liver mitochondria could still be induced to undergo the CsA-inhibitable permeability transition by sequential addition of Ca2+ (Fig. 3c). Thus, the existence of a functional mtPTP in the absence of ANT was confirmed. However, threefold more Ca2+ was required to activate the mtPTP in the ANT-deficient mitochondria than in the ANT-control mitochondria (Fig. 3c).

Furthermore, in both ANT-deficient and ANT-control mitochondria, activation of the mtPTP (as monitored by Ca2+-induced TPP+ release—that is, the permeability transition) was associated with the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria into the supernatant. By contrast, the inner membrane COI protein remained associated with the mitochondrial pellets (Fig. 3d). The ANT-deficient mitochondria contained more cytochrome c than did controls, so the mutant mitochondria released more cytochrome c (Fig. 3d). Hence, ANTs are also not required for mtPTP-induced cytochrome c release, confirming that the mtPTP can function in the absence of ANT.

Next, we investigated whether ANTs regulate the function of the mtPTP. ANT-deficient and control liver mitochondria were loaded with TPP+ and then exposed to various mtPTP effectors. Tert-butyl hydroperoxide (t-H2O2), a non-specific oxidant, and diamide, a specific –SH group oxidant, are both inducers of the mtPTP14. These compounds increased the predilection of the mtPTP to undergo the permeability transition, independent of the presence of ANT (Fig. 3e, f). The ANT ligands atractyloside (ATR) and ADP are positive and negative effectors of the mtPTP, respectively15,16. Although ATR activated and ADP inhibited the mtPTP in ANT-control mitochondria, they had no effect on ANT-deficient mitochondria (Fig. 3e, f). Thus, the absence of ANT results in the loss of the modulation of the mtPTP by ANT ligands, including adenine nucleotides.

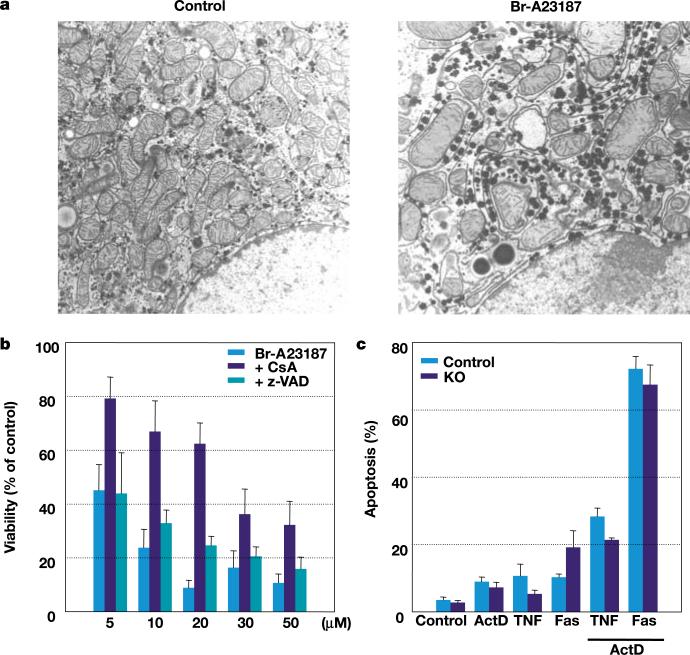

We next investigated whether absence of ANTs affected the response of cultured hepatocytes to inducers of apoptosis and necrosis (Fig. 4). Mitochondrial swelling (Fig. 4a) and cell death (Fig. 4b) occurred in ANT-deficient (Ant1–/–, Ant2fl/Y, Alb-Cre) hepatocytes after exposure to the calcium ionophore Br-A23187 (ref. 17). This was partially inhibited by pretreatment with CsA but not with the general caspase inhibitor z-VAD (Fig. 4b). In fact, ANT-deficient hepatocytes were more sensitive to Br-A23187 than were ANT-control cells, suggesting that ANT-deficiency may presensitize the mitochondria to the permeability transition. Moreover, no difference was observed in the sensitivity of ANT-deficient and ANT-control hepatocytes to treatment with soluble Fas ligand or tumour-necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) in the presence of actinomycin D18 (Fig. 4c). Hence, ANTs are not required for mitochondrial permeability transition or for these forms of mitochondria-mediated hepatocyte cell death.

Figure 4.

Induction of cell death in ANT-deficient mouse hepatocytes. a, Transmission electron microscope images of ANT-deficient hepatocytes. Control, untreated; Br-A23187, treated for 1 h with 10 μM Br-A23187. b, Calcium ionophore (Br-A23187) induced cell death (% of LDH released) of ANT-deficient treated hepatocytes relative to untreated hepatocytes, without or with pretreatment by either CsA or z-VAD. c, Receptor-mediated apoptosis (Hoechst 33258 analysed nuclear fragmentation) induced by TNF-α or soluble Fas ligand treatment, with or without actinomycin D (ActD). KO, knockout.

In conclusion, our studies reveal that the ANTs are non-essential components of the mtPTP and that they are dispensable for at least some forms of mtPTP-associated cell death. However, the ANTs do have an essential role in regulating permeability transition by modulating the sensitivity of the mtPTP to Ca2+ activation and ANT ligands.

Methods

Ant2fl mice on a mixed 129S4 and C57BL/6 background were generated using standard methods under a protocol approved by Emory University's IACUC. The targeting vector contained a floxed Ant2 gene with a PGK-neo cassette added to the 3′-untranslated region (Fig. 1a). Targeted AK7.1 embryonic stem cell clones were identified by Southern analysis (Fig. 1b). The 5′-probe (probe A) detected a 12.8-kilobase (kb) Xba I fragment for the wild-type Ant2 allele and a 6.6-kb fragment for the targeted allele. The 3′-probe (probe B) detected a 7.9-kb Dra III fragment for the wild-type allele and a 13.8-kb fragment for the targeted allele. Site-specific recombination between the loxP sites removed the last third of the ANT2 coding sequence, including putative transmembrane domains 5 and 6, plus the PGK-neo cassette, generating a non-functional protein.

Ant2 was genotyped by PCR (forward primer 5′-ACTCAACCTAGGGCCTTGTG-3′, reverse primer 5′-GGGAGCATTCCTGAAAAATAA-3′; 35 cycles at 94 °C for 20 s; at 56 °C for 30 s; at 72 °C for 40 s) to detect the targeted (485 base pairs, bp) and wild-type (384 bp) alleles. The mutant Ant2 allele (850 bp) was detected using the same forward primer and reverse primer 5′-GACTTACCCTCCACGACAGC-3′; 35 cycles at 94 °C for 20 s; at 65 °C for 30 s; at 72 °C for 60 s. Genotyping at Ant1 was determined as described5.

For western blots, isoform-specific ANT1 and ANT2 antibodies5, and antibodies recognizing COI, UCP2 and cytochrome c (Molecular Probes and Zymed) were employed. These were reacted to isolated mitochondrial protein (20 μg) or supernatants separated by SDS–PAGE and blotted onto nitrocellulose.

Mitochondria were isolated from liver by homogenization followed by differential centrifugation. Respiration and OXPHOS enzyme activities were normalized for protein concentration using the Coomassie Stain kit (Pierce)13,19. Mitochondrial membrane potential was calculated from mitochondrial uptake of TPP+ using a TPP+-sensitive electrode . The sensitivity of the mtPTP to undergo permeability transition was examined in liver mitochondria of 10-month-old Ant1–/–, Ant2fl/Y, Alb-Cre animals by TPP+ release after sequential additions of 10 nM CaCl2 (ref. 13). The mtPTP modulators used were 1 mM t-H2O2, 0.1 mM diamide, 100 μM ATR and 125 μM ADP (Fig. 3).

Mitochondrial PTP activation was also monitored by mitochondrial swelling using light scattering at 546 nm for 10 min in 1.5 ml with 1 mg mitochondrial protein and 16.5 nmol CaCl2. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 0.1 μM ruthenium red and 1 μM FCCP.

Hepatocytes were isolated from 12- to 15-month-old anaesthetized mice, perfused in situ with collagenase-dispase medium (Invitrogen). Hepatocytes were gently released, filtered and cultured on collagen-coated cover glasses or plates in Waymouth's MB-752/1 medium17. Hepatocyte sensitivity to Ca2+ ionophore was examined by extent of cell death assessed by the percentage of total cellular lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released into the medium20 after treatment with 5 to 50 μM Br-A23187 for 1 h, without or with a 30 min pretreatment of either 1 μM CsA or 50 μM z-VAD 17 (Fig. 4). Receptor-induced cell death was monitored by analysis of nuclear morphology using Hoechst 33258 (Molecular Probes) staining after treatment with 100 ng ml–1 of murine recombinant TNF-α (R&D Systems) or 4 ng ml–1 of human recombinant Fas ligand (Upstate), with or without 0.2 μg ml–1 actinomycin D (Fig. 4).

Acknowledgements

We thank M. Magnuson for providing the Alb-Cre transgenic mice, L. Hayes for mouse husbandry and genotyping, and H. Yi for the electron microscope analysis. This work was funded by US National Institutes of Health grants awarded to D.C.W., G.R.M. and D.P.J.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement The authors declare competing financial interests: details accompany the paper on www.nature.com/nature.

References

- 1.Zoratti M, Szabo I. The mitochondrial permeability transition. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1995;1241:139–176. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(95)00003-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marzo I, et al. Bax and adenine nucleotide translocator cooperate in the mitochondrial control of apoptosis. Science. 1998;281:2027–2031. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5385.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy SE, Chen Y-S, Graham BH, Wallace DC. Expression and sequence analysis of the mouse adenine nucleotide translocase 1 and 2 genes. Gene. 2000;254:57–66. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00252-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellison JW, Salido EC, Shapiro LJ. Genetic mapping of the adenine nucleotide translocase-2 gene (Ant2) to the mouse proximal X chromosome. Genomics. 1996;36:369–371. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graham B, et al. A mouse model for mitochondrial myopathy and cardiomyopathy resulting from a deficiency in the heart/skeletal muscle isoform of the adenine nucleotide translocator. Nature Genet. 1997;16:226–234. doi: 10.1038/ng0797-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stepien G, Torroni A, Chung AB, Hodge JA, Wallace DC. Differential expression of adenine nucleotide translocator isoforms in mammalian tissues and during muscle cell differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:14592–14597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lunardi J, Hurko O, Engel WK, Attardi G. The multiple ADP/ATP translocase genes are differentially expressed during human muscle development. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:15267–15270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Postic C, Magnuson MA. DNA excision in liver by an albumin-Cre transgene occurs progressively with age. Genesis. 2000;26:149–150. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1526-968x(200002)26:2<149::aid-gene16>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boss O, Hagen T, Lowell BB. Uncoupling proteins 2 and 3: potential regulators of mitochondrial energy metabolism. Diabetes. 2000;49:143–156. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.2.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petronilli V, Nicolli A, Costantini P, Colonna R, Bernardi P. Regulation of the permeability transition pore, a voltage-dependent mitochondrial channel inhibited by cyclosporin A. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1994;1187:255–259. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(94)90122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernardi P. Modulation of the mitochondrial cyclosporin A-sensitive permeability transition pore by the proton electrochemical gradient. Evidence that the pore can be opened by membrane depolarization. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:8834–8839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Esposito LA, et al. Mitochondrial oxidative stress in mice lacking the glutathione peroxidase-1 gene. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000;28:754–766. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00161-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kokoszka JE, Coskun P, Esposito L, Wallace DC. Increased mitochondrial oxidative stress in the Sod2 mouse results in the age-related decline of mitochondrial function culminating in increased apoptosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:2278–2283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051627098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halestrap AP, Woodfield KY, Connern CP. Oxidative stress, thiol reagents, and membrane potential modulate the mitochondrial permeability transition by affecting nucleotide binding to the adenine nucleotide translocase. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:3346–3354. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lapidus RG, Sokolove PM. The mitochondrial permeability transition. Interactions of spermine, ADP, and inorganic phosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:18931–18936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Novgorodov SA, Gudz TI, Brierley GP, Pfeiffer DR. Magnesium ion modulates the sensitivity of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore to cyclosporin A and ADP. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1994;311:219–228. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qian T, Herman B, Lemasters JJ. The mitochondrial permeability transition mediates both necrotic and apoptotic death of hepatocytes exposed to Br-A23187. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1999;154:117–125. doi: 10.1006/taap.1998.8580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hatano E, et al. The mitochondrial permeability transition augments Fas-induced apoptosis in mouse hepatocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:11814–11823. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.11814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trounce IA, Kim YL, Jun AS, Wallace DC. Assessment of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in patient muscle biopsies, lymphoblasts, and transmitochondrial cell lines. Methods Enzymol. 1996;264:484–509. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)64044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leist M, et al. Murine hepatocyte apoptosis induced in vitro and in vivo by TNF-α requires transcriptional arrest. J. Immunol. 1994;153:1778–1788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]