Abstract

Oxidative stress resulting from mitochondrially derived reactive oxygen species (ROS) has been hypothesized to damage mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and to be a factor in aging and degenerative disease. If this hypothesis is correct, then genetically inactivating potential mitochondrial antioxidant enzymes such as glutathione peroxidase-1 (Gpx1; EC 1.11.1.9) should increase mitochondrial ROS production and decrease OXPHOS function. To determine the expression pattern of Gpx1, isoform-specific antibodies were generated and mutant mice were prepared in which the Gpx1 protein was substituted for by β-galactosidase, driven by the Gpx1 promoter. These experiments revealed that Gpx1 is highly expressed in both the mitochondria and the cytosol of the liver and kidney, but poorly expressed in heart and muscle. To determine the physiological importance of Gpx1, mice lacking Gpx1 were generated by targeted mutagenesis in mouse ES cells. Homozygous mutant Gpx1tm1Mgr mice have 20% less body weight than normal animals and increased levels of lipid peroxides in the liver. Moreover, the liver mitochondria were found to release markedly increased hydrogen peroxide, a Gpx1 substrate, and have decreased mitochondrial respiratory control ratio and power output index. Hence, genetic inactivation of Gpx1 resulted in growth retardation, presumably due in part to reduced mitochondrial energy production as a product of increased oxidative stress.

Keywords: Mitochondria, Hydrogen peroxide, Glutathione peroxidase, Oxidative phosphorylation, Oxidative stress, Knockout mice, Free radicals

INTRODUCTION

Oxidative stress resulting from increased levels of ROS, (O2•−, H2O2, •OH), is believed to have profound effects on mitochondria. Mitochondria are the site of ATP synthesis by OXPHOS and OXPHOS is the major source of ROS in the cell [1,2]. Organisms have evolved extensive enzymatic defense systems to protect against the deleterious effects of mitochondrial oxidants. The primary mitochondrial enzymes are Mn superoxide dismutase (Sod2), which converts O2•− to H2O2 [3] and Gpx1, which converts H2O2 to H2O [4].

The potential toxicity of mitochondrial superoxide has been established through the studies on mice deficient in Sod2. Homozygous mutant Sod2 mice display neonatal lethality due to inactivation of iron-sulfur centers in OXPHOS and citric acid cycle enzymes [5,6]. In contrast, heterozygous mutant Sod2 animals have a partial OXPHOS defect involving a reduced respiratory control ratio (RCR) and an increased propensity for the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mtPTP) [7]. The opening of the mtPTP creates a channel through the inner and outer mitochondrial membranes permitting free diffusion of molecules of 1500 kDa or less. This results in the loss of the mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨ), the swelling of the mitochondria, and the initiation of apoptosis [8].

Gpx1 catalyzes the reactions:

(where ROOH is a hydroperoxide and ROH the corresponding alcohol) [4]. Because H2O2 is a Fenton reagent and a direct precursor to the highly toxic •OH [9], we hypothesized that mice lacking the Gpx1 gene would exhibit impaired mitochondrial function in tissues that express the highest levels of mitochondrial Gpx1.

Initial studies of homozygous mutant Gpx1 mice failed to reveal any major abnormal phenotypes under normal conditions and upon exposure to hyperbaric oxygen [10], although an analysis of an independent Gpx1 mutant mouse line revealed that the mice were more susceptible than wild type controls to oxidative insults such as paraquat and H2O2 [11]. These studies suggested that Gpx1 deficiency might not be sufficient by itself to cause toxic oxidative stress. It is possible that the Gpx1 deficiency is compensated by another Gpx isoform and/or catalase. For example, the phospholipid Gpx (Gpx4; EC 1.11.1.12) is proposed to have a role in the mitochondria [12,13] and may compensate for the loss of Gpx1.

To learn more about the role of Gpx1 in protecting mitochondria from oxidative stress, we prepared two new mouse Gpx1 mutants by homologous recombination in embryonic stem (ES) cells. In one mutant we have substituted the Gpx1 gene for a β-galactosidase fusion protein driven by the Gpx1 promoter. This permitted us to define the tissue expression of this gene. Second, we inactivated the gene by insertion of a PGKneo cassette, and showed that the Gpx1-deficient mice are smaller than wild type littermates and that affected tissues had increased mitochondrial H2O2 production, increased lipid peroxides, and decreased mitochondrial energy output. Hence, Gpx1 does play a significant role in inhibiting mitochondrial ROS production, thus protecting the animal from oxidative stress.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning Gpx1 genomic locus

A 14.6 kb Gpx1 genomic clone was isolated from a bacteriophage λ Dash II genomic library constructed with DNA from a 129/Svs3 (+Mgf, +c,+p) mouse. Plaques were screened by filter hybridization by using a 289 base pair (bp) probe spanning the border between intron 1 and exon 2 of the Gpx1 gene [14]. The 14.6 kb genomic insert was excised from the bacteriophage by NotI digestion, subcloned into pBluescript (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) and further characterized by Southern blotting and restriction mapping.

A 4.1 kb EcoRI fragment of the 14.6 kb insert was obtained by EcoRI partial digest and subcloned into the EcoRI site of pBluescript. Sequence analysis of both strands of the 4.1 kb insert was carried out by “walking” along the fragment beginning with T3 and T7 sequencing primers located in pBluescript. A 10.9 kb BclI genomic fragment, containing the entire mouse Gpx1 gene, was then used in construction of the targeting vectors (Figs. 1 and 3).

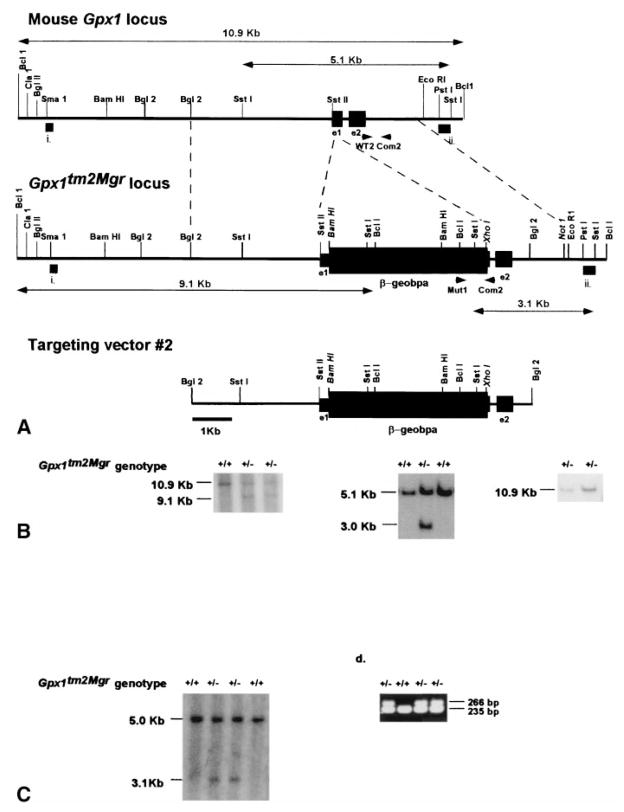

Fig. 1.

Generation of Gpx1tm2Mgr (−/−) mice. (A) Diagram of the desired homologous recombination event occurring in ES cells to create the Gpx1tm2Mgr mutant allele. The top line represents a partial restriction map of the wild type Gpx1 locus with exons 1 and 2 (smaller black rectangles) indicated. The Gpx1tm2Mgrtargeting vector is shown on the bottom, with the fusion between exon 1 of Gpx1 (smaller black rectangle) and the β-geobpA cassette (larger black rectangle) shown. Selection for proper homologous recombination of the targeted construct in ES cells, shown in the middle, requires expression of the fusion gene product driven by the endogenous Gpx1 promoter. The thick bars indicated as (i) and (ii) indicate the 5′ and 3′ probes used in the Southern analysis shown in (B). The internal neo probe is not shown. The small arrow heads indicate the PCR primers used in (D) to detect the wild type and mutant alleles. The double arrow lines above and below the wild type and mutant alleles, respectively, indicate the BclI (10.9 and 9.1 kb) and SstI (5.1 kb and 3.1 kb) fragments detected by the probes. Restriction enzymes in italics indicate artificial sites created by PCR cloning of the desired genomic fragment for constructing the targeting vector. (B) Southern analysis of neomycin-resistant ES cell clones. Southern blots contain BclI-digested (left and right) and SstI-digested (middle) genomic DNA, probed with 5′ (left) and 3′ (middle) probes (external to the homologous arms of the targeting vector), as well as an internal neo probe (right) to detect possible tandem insertions. The deduced genotype of each clone is shown above the lanes. (C) Southern analysis of intercross progeny for the presence of the Gpx1tm2Mgr mutant allele. SstI-digested genomic DNA was probed with the 3′ probe as in (A). (D) Multiplex PCR screen of intercross progeny for the presence of the Gpx1tm2Mgr mutant allele. The position of the PCR primers are indicated in (A).

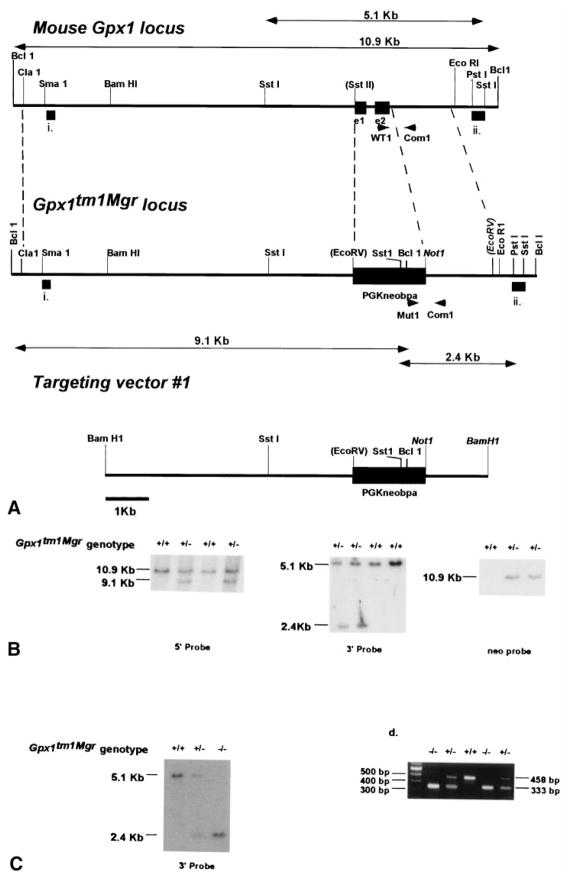

Fig. 3.

Generation of Gpx1tm1Mgr mice. (A) Diagram of the desired homologous recombination event occurring in ES cells to create the Gpx1tm1Mgr mutant allele. The top line indicates a partial restriction map of the wild type Gpx1 locus as in Fig. 1A. The bottom line shows the Gpx1tm1Mgr targeting vector, containing the PGKneo cassette (larger black rectangle). The final targeted allele, with exons 1 and 2 of Gpx1 replaced by the PGKneo cassette, is shown in the middle, with the regions of homology indicated. Probes for Southern analysis and PCR primers are indicated as in Fig. 1A. The double arrow lines above and below the wild type and mutant alleles respectively indicate the BclI (10.9 kb and 9.1 kb) and SstI (5.1 and 2.4 kb) fragments detected by the probes. Restriction enzymes in parentheses indicate restriction sites destroyed in constructing the targeting vector and restriction enzymes in italics indicate artificial sites created by PCR cloning of the desired genomic fragment for constructing and linearizing the targeting vector. (B) Southern analysis of neomycin-resistant ES cells clones shown as in Fig. 1B. (C) Southern analysis of intercross progeny for the presence of the Gpx1tm1Mgr mutant allele shown as in Fig. 1C. (D) Multiplex PCR screen of intercross progeny for the presence of the Gpx1tm1Mgr mutant allele shown as in Fig. 1D.

Construction of gene targeting vectors and generation of mutant mice

The Gpx1 genomic locus was disrupted using two strategies. In the first strategy (Gpx1tm2Mgr, see Fig. 1), an in-frame fusion between Gpx1 and the β-galactosidase-neomycin resistance (pBSβ-geobpA cassette) [15] was created. This involved the cloning of a 5.7 kb BamHI-BamHI fragment of Gpx1 (containing the first 56 amino acids of exon 1) into the BamHI site of pBSβ-geobpA (5′ end). Then, the 2.0 kb XhoI-NotI fragment of Gpx1 was cloned into the XhoI-NotI fragment of pBSβ-geobpA (3′ end). Proper orientation and reading frame were confirmed by restriction mapping and sequence analysis. This targeting vector was linearized with BglII. Northern analysis of 129/Svs3 ES cell RNA with a mouse Gpx1 cDNA probe revealed that Gpx1 is expressed in ES cells (data not shown).

In the second strategy (Gpx1tm1Mgr, Fig. 3), the two Gpx1 exons were replaced with the neomycin resistance protein driven by a phosphoglycerate kinase-1 promoter (PGKneobpA). First, a 7.8 kb ClaI-SstII Gpx1 fragment was directional blunt-end cloned into the ClaI- EcoRV fragment of PGKneobpA [16] (5′ end). Second, a 1.5 kb NotI-EcoRV Gpx1 fragment was directional blunt-end cloned into the NotI-SstII fragment of PGKneobpA (3′ end). This targeting vector was linearized with BamHI.

For each targeting vector, 25 μg of linearized DNA was introduced into AK7.1 129/Svs3 embryonic stem (ES) cells by electroporation [17]. Neomycin-resistant clones were selected with G418 (Gibco, Rockford, MD, USA; 300 μg/ml). Properly targeted homologous recombinants (2/500 for Gpx1tm1Mgr and 5/162 for Gpx1tm2Mgr) were identified by Southern analysis, first by using 5′ and 3′ genomic DNA probes from regions external to the homologous arms of the targeting vectors (indicated as thick bars i. and ii. in Figs. 1 and 3), and then by using an internal neo probe. Correctly targeted clones were injected into C57BL/6J blastocysts and the resulting male chimeras were bred with C57BL/6J females for targeted allele transmission in hybrid animals (129B6-Gpx1tm1Mgr mice) or with 129/Svs3 females for transmission in inbred animals (129-Gpx1tm1Mgr mice). All ES cell culture, Southern blot, and microinjection techniques were performed using standard procedures [17,18].

PCR genotyping of Gpx1tm1Mgr and Gpx1tm2Mgr mice and animal maintenance

Genotyping of Gpx1tm1Mgr and Gpx1tm2Mgr mice was performed using a 3 primer, multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) reaction (indicated as arrowheads in Figs. 1 and 3). For Gpx1tm2Mgr mice (Fig. 1), the primers used are (5′–3′): wild type-specific primer 2 (WT2) = AGAT-GAAACGATCTGCAGAAGCGTC; neo-specific primer (Mut1) = AGGATTGGGAAGACAATAGCAGGCA; and common primer 2 (Com2)= GCAAAACAGAGGTT-TCCCGATGAG. This gives the products (WT2 + Com2) = 235 bp and (Mut1 + Com2) = 266 bp. For Gpx1tm1Mgr mice (see Fig. 3), the primers used are (5′–3′): wild type-specific primer 1 (WT1) = GTACATCATTTG-GTCTCCGGTGTG; neo-specific primer (Mut1); and common primer 1 (Com1) = GACGTTTAGGCTCTGGGAT-TGAGT. This gives the products (WT1 + Com1) = 458 bp and (Mut1 + Com1) = 333 bp.

The oligonucleotides were synthesized by the Emory University Microchemical Facility. Toe biopsies of 7–9 day old pups were taken, and the tissue was digested for 15 min at 55°C in 50 μl of 1× PCR buffer (10 mM tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2), 0.5 mg/ml proteinase K, 0.05% nonidet P-40 (NP-40), and 0.05% Tween-20. After proteinase K inactivation (15 min at 95°C), 2 μl were used in a 50 μl PCR reaction consisting of 1× PCR mix (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM dNTPs, 300 nM each primer, and 0.02 U/μl Expand Long Extension Taq Polymerase (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN, USA). All PCR reactions were cycled in a Perkin Elmer 9600 thermocycler with the following profile: denaturation at 94°C for 2 min, then 35 cycles of 94°C for 10 s, 65°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 45 s, and ending with 72°C for 5 min. Twenty microliters of each reaction was then electrophoresed through a 1.6% agarose gel (Gibco) and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Adult mice were fed Purina (Richmond, IN, USA) Labdiet 5010 (ad libitum), were given free access to acidified (pH 3.0) water and were housed under standard conditions. 129B6-Gpx1tm1Mgr mice were used for growth analysis of 1–53 d old animals and for analysis at 8 months of age. For biochemical analyses, animals were killed by cervical dislocation in accordance with guidelines approved by an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) protocol.

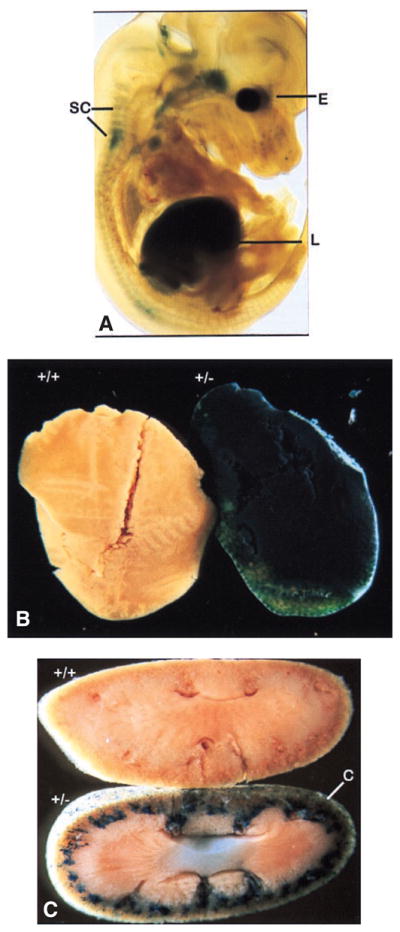

In situ detection of β-galactosidase activity by X-Gal staining

All tissues of E13.5 embryo and adult animals were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde in 100 mM sodium phosphate (Na2PO4), pH 7.4 containing 0.01% sodium de-oxycholate, 0.2% glutaraldehyde (EM grade), and 0.02% NP-40 on ice for 1–2 h. The fixed tissues were rinsed four times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and stained (18 h for tissues, 30 h for embryos) at 37°C in 77 mM Na2HPO4, 23 mM NaH2PO4, 3 mM K3Fe(CN)6, 3 mM K4Fe(CN)6, 1.0 mg/ml 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoyl-β-D-galactoside (X-Gal), 1.3 mM MgCl2, 0.01% sodium deoxycholate (NaC24H39O4) and 0.02% nonidet-P40, pH 7.3 [15]. Embryos were serially dehydrated in ethanol, cleared in methyl salicylate (oil of wintergreen) and photographed, whereas the adult tissues were photographed hydrated.

Tissue harvesting for mitochondrial isolation

All manipulations were performed at 4°C or on ice to minimize mitochondrial membrane and protein degradation. Whole liver, kidney, heart, skeletal muscle, and brain from 6–9 month old or 14–16 month old wild type and 129B6-Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) or 129-Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) mice were harvested and immersed in isotonic homogenization buffer (H buffer; 225 mM mannitol, 75 mM sucrose, 10 mM 3-(N-morpholino) propane sulfonic acid, 1 mM ethylene glycol-bis (2-aminoethyl)-N,N,N′N′-tetraacetic acid, 0.5% bovine serum albumin pH 7.2) [19].

Mitochondrial isolation

Mitochondria were isolated by differential centrifugation [19]. Heart, kidney, and skeletal muscle were finely minced using a tissue slicer and homogenized with the aid of a motor-driven pestle, whereas other tissues were minced with scissors and homogenized [20].

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was carried out by using polyclonal antibodies. The Gpx1 antibody was raised against the C-terminal region [20]. The Gpx4 antibody was raised against the near C-terminal oligopeptide: acetyl-(C)GPMEEPQVIEKD-amide (13-amino acid peptide). The peptide was conjugated to the carrier protein keyhole limpet hemocyanin via the foreign cysteine (C) and injected into rabbits at Quality Controlled Biochemicals (Hopkinton, MA, USA). Antisera were collected and sequentially purified by affinity chromatography on 2 peptide–Sepharose columns, the first containing the 13-amino acid peptide shown above, and the second containing a 9-amino acid peptide identical to the 13-mer except lacking the amino acids IEKD.

Twenty micrograms of cellular lysate or isolated mitochondrial protein were electrophoresed and blotted onto nitrocellulose and probed with Gpx1 or Gpx4 antiserum by using the Western Blot Kit (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and Amersham ECL substrate (Arlington Heights, IL, USA). To assure approximately equal loading of total protein on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel-electrophoresis gels, immunoblots were reversibly stained with Ponceau S dye (2 g/l in 1% (vol/vol) acetic acid solution) and photographed. Ponceau S was removed by rinsing for 10 min in PBS, pH 7.2 containing 0.5 ml/l Tween 20, before incubation with the anti-Gpx antibody.

Mitochondrial hydrogen peroxide generation assay

Hydrogen peroxide efflux from isolated mitochondria was measured with the p-hydroxyphenylacetate (PHPA) fluorescence method [21,22], using 100–200 μg of mitochondrial protein per assay. Succinate was added as a substrate at a final concentration of 6.5 mM. Fluorescence intensity (320 nm excitation; 400 nm emission) was measured for each 10-min reaction in a Perkin-Elmer (Foster City, CA, USA) LS50B fluorescence spectrometer by using FLWinlab software. After the measurement of the intrinsic rate of mitochondrial H2O2 production for the first 5 min of the reaction, 60 μM antimycin A was added to determine the maximal rate. Catalase (1000 U) was added 3 min later resulting in a brief decrement in PHPA fluorescence confirming the H2O2 identity. Pure H2O2 (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) was used to construct a standard curve of 11.8, 23.6, 47.2, 70.8, and 94.4 pmole of H2O2 per 3 ml.

Mitochondrial respiration

Oxygen consumption was measured polarographically with a Clark electrode. Mitochondrial incubation buffer was composed of 225 mM mannitol, 75 mM sucrose, 10 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.2. Three hundred to six hundred micrograms of mitochondrial protein was used per assay with 5 mM glutamate and 5 mM malate as respiratory substrates. One hundred and twenty-five nanomoles adenosine diphosphate (ADP) was added to measure state III respiration [19].

Mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨ)

The mitochondrial electrochemical potential (ΔΨ) was measured by the mitochondrial uptake of tetraphenylphosphonium cation (TPP+) [23–25]. The concentration was measured using a TPP+-sensitive electrode. ΔΨ was calculated using the equation ΔΨ = 2.303 × RT/F × log (v/V) − 2.303 RT/F × log [10FΔE/2.303RT − 1] where v is the mitochondria volume, V is the volume of the incubation medium alone, R is the gas constant, T is the temperature, F is the Faraday constant, and ΔE is the experimentally determined deflection of the TPP electrode from the baseline before injection of mitochondria [24]. Measurements were made in 1 ml incubation buffer (250 mM sucrose, 10 mM MOPS, and 2 mM K2HPO4, pH 7.2) with 600 μg mitochondrial protein, and 3.5 mM succinate. The following additions were made where indicated: Cyclosporin A (0.60 μM) + ADP (0.125 mM); oligomycin (2.5 ng/ml) + ADP (0.125 mM); or carboxyatractyloside (5 μM) + ADP (.25 mM) + oligomycin (2.5 ng/ml). The constants used for TPP+ binding to inside (IBC) and outside (EBC) of liver mitochondria were determined in rat and are IBC = 7.45 and EBC = 55 [26].

Lipid peroxidation assay

Levels of lipid peroxides in mitochondria and total organellar extracts were measured directly by using the Lipid Hydroperoxide Assay kit (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, Catalog # 705002). Mitochondria (liver and heart) were prepared as above and total organellar extracts (liver only) were prepared by using the same method except the two centrifugation steps at 10,000 × g were omitted. For each assay, total lipid was extracted from a volume of extract or suspension of mitochondria containing 1 mg of protein.

Induction of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore

Calcium-induced collapse of ΔΨ was used to indicate the opening of the permeability transition pore. Calcium ion (Ca+2) was added stepwise as CaCl2 until ΔΨ collapsed, which was detected by the release of TPP+ from the mitochondrial matrix [1].

Mitochondrial matrix glutathione peroxidase activity assay

Mitochondrial matrix extract was prepared by sonicating isolated liver and heart mitochondria for 15 s on ice. The homogenate was clarified by centrifugation at 10,000 × g at 4°C for 5 min and the resulting supernatant used in the glutathione peroxidase assay. Total glutathione peroxidase activity was determined by the indirect, coupled test procedure [10]. Briefly, the GSSG produced during the Gpx enzyme reaction is immediately reduced by glutathione reductase and reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH). Therefore, the rate of NADPH consumption (monitored as a decrease in absorbance at 340 nm) is a measurement of the GSSG formed during the Gpx reaction. The reaction was carried out in a buffer containing 20 mM potassium phosphate, (pH 7.0), 0.6 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 0.15 mM NADPH, 4 units of glutathione reductase, 2 mM GSH, 1 mM sodium azide, and 0.1 mM H2O2 at 25°C. The Gpx activity, U, is defined 1 μmol NADPH consumed per minute. Specific activities are presented as mU/mg mitochondrial protein.

RESULTS

Using a probe specific for mouse Gpx1, we screened a mouse genomic library and identified a clone containing a 14.6 kb insert. The entire coding sequence of the mouse Gpx1 gene is found within a 5.1 kb SstI fragment. Sequence analysis of a 4.0 kb EcoRI fragment found within the SstI fragment (data not shown) revealed a gene structure and sequence nearly identical to that previously published for a smaller region of the Gpx1 locus [14].

To further define the cellular expression pattern of Gpx1 in mice, we created a “knock-in” mutant allele of Gpx1 by homologous recombination in ES cells, inserting a “promoterless” β-geo cassette in-frame into exon 1 (Fig. 1A). The β-geo gene product is a chimaeric protein containing both β-galactosidase activity and neomycin resistance [27]. The mutant allele expresses a fusion transcript consisting of the first third of the Gpx1 coding region (most of exon 1) and β-geo. Because this targeted allele’s expression is driven from the endogenous Gpx1 promoter, we can utilize expression of β-galactosidase activity to monitor the tissue-specific transcription of the Gpx1 gene (in situ).

The targeting construct was transfected into 129/Svs3-derived ES cells, G418-resistant clones were selected, and clones were screened by Southern blot analysis for homologous recombination events (Fig. 1B). Targeted ES cell clones were used to introduce this mutant allele into the germ line. Mice carrying the mutant allele were genotyped by Southern blot and PCR analysis (Figs. 1C and 1D).

Expression of Gpx1 was analyzed in the tissues of embryonic and adult heterozygous Gpx1tm2Mgr mice. X-Gal staining of day 13.5 (E13.5) embryos (n = 1) revealed Gpx1tm2Mgr expression in the liver, spinal cord, and eye and a distinctive pattern in brain consistent with brain stem (Fig. 2A). Analysis of adult tissues (n = 3) revealed highest levels of expression in liver (Fig. 2B) and kidney cortex (Fig. 2C), consistent with Western (see below) and Northern [10] analysis. Very little staining was detected in heart, skeletal muscle, lung, and spleen (data not shown), tissues reported to express Gpx1 at lower levels (see below, and [10]). No background staining was detected in any of the wild type tissues (n = 7 for embryos; n = 3 for adult tissues) that lack the Gpx1tm2Mgr mutant allele (data not shown). This suggests that the Gpx1tm2Mgr mutant allele faithfully reflects expression of the Gpx1 gene in tissues in which Gpx1 is highly expressed.

Fig. 2.

Expression analysis of Gpx1 using X-Gal-stained mouse tissues. (A) X-Gal stained heterozygous Gpx1tm2Mgr embryo at e13.5. E = eye, SC = spinal column, L = Liver. (B) X-Gal stained wild type (+/+, left) and heterozygous Gpx1tm2Mgr (+/−; right) adult liver. (C) X-Gal stained wild type (+/+, top) and heterozygous Gpx1tm2Mgr (+/−; bottom) kidney. C = cortex layer.

In addition to the β-geo “knock-in” allele, a mutant allele of Gpx1 was created in which both exons of Gpx1 were replaced with a PGKneo cassette that has an efficient polyadenylation signal (Fig. 3A). This mutant allele is predicted to be null for Gpx1 activity. Targeted ES cell clones were identified (Fig. 3B) and the mutation transmitted into the germ line, as described for the Gpx1tm2Mgr allele. F1 heterozygotes were generated by the mating of male chimeras with C57BL/6J (B6) females. After a single backcross generation with B6 females, N2 Gpx1tm1Mgrheterozygotes were intercrossed and the progeny genotyped by either Southern blot (Fig. 3C) or PCR analysis (Fig. 3D). The cumulative genotype ratios (+/+, +/−, −/−) of N2F1 offspring conformed to the expected mendelian ratios (1:2:1). Thus, N2F1 129B6-Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) mice are viable. To obtain mice with the Gpx1tm1Mgr mutation on an inbred genetic background, male chimeras exhibiting germline transmission of the Gpx1tm1Mgr allele were mated with females of a 129/Svs3 strain from which the AK7.1 ES cell line was derived. The progeny were screened by PCR. F1 129-Gpx1tm1Mgr heterozygotes were intercrossed and the progeny genotyped by PCR. On both the hybrid and inbred background, the Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) mice are viable, fertile, and exhibit normal growth characteristics up to 2 months of age.

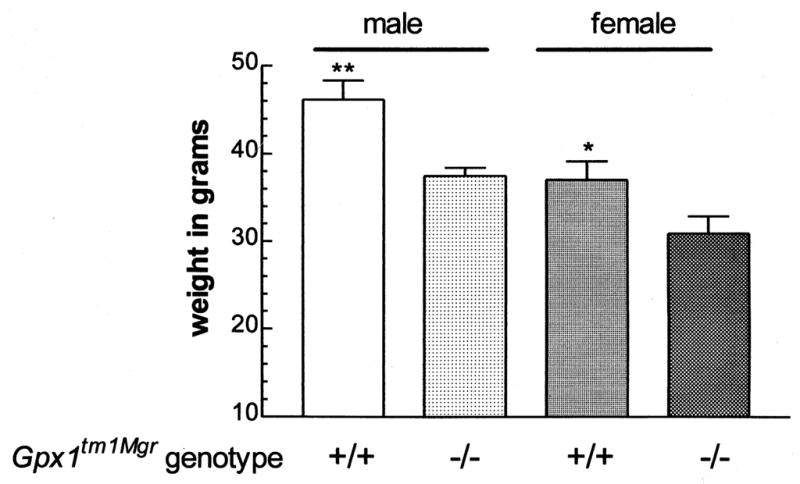

To determine if Gpx1-deficiency had any effect on homeostasis in adult mice, the animals were routinely examined for gross physical change, including overall weight. A clear phenotypic difference was seen for the 129B6-Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) animals at 8 months of age. The weights of the Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) animals were 20% less than those of wild type (+/+) controls (Fig. 4). This suggests that the GPx1-deficiency has an adverse effect on the physiology of the mutant animals.

Fig. 4.

129B6-Gpx1tm1Mgr mice are smaller than wild type animals by 8 months of age. The bars represent the mean ± SEM for each group. *p < .05; **p < .01 for wild type (+/+) as compared with (−/−) mice of the same sex; n = 15–16 for males, 10–12 for females from each group.

In contrast to total body weight, there were no differences in tissue weights (normalized to body weights) for liver, kidney, or heart between wild type and Gpx1-deficient mice.

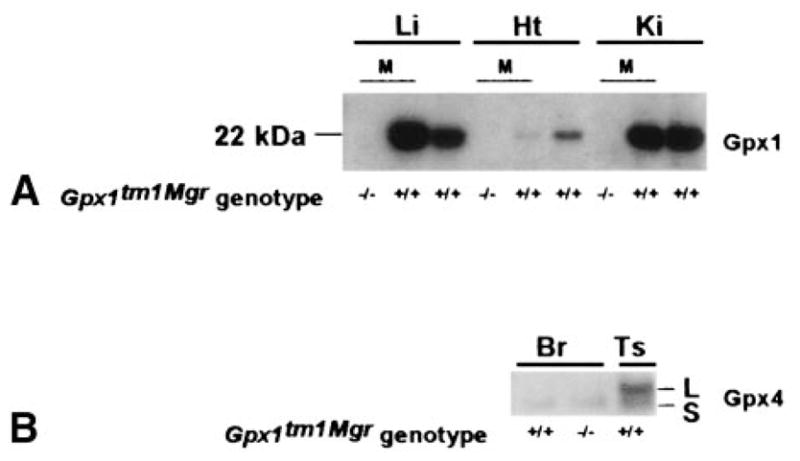

To define the cellular and subcellular distribution of the selenium-dependent glutathione peroxidases in different tissues, we prepared isoform-specific antibodies to Gpx1 and Gpx4 and performed Western blot analysis on mouse tissue lysates and isolated mitochondria. These results show that in normal animals, very high levels of Gpx1 are found in liver and kidney with moderate levels in heart (Fig. 5A). Moderate levels of Gpx1 protein was also detected in normal animals in the brain and testis, but very low levels were found in skeletal muscle (data not shown). In contrast, a very limited pattern of expression was seen for Gpx4, with expression detected only in testis and brain (Fig. 5B). Unlike Gpx1, which lacks an amino-terminal mitochondrial targeting sequence, the cytosolic and mitochondrial forms of Gpx4 differ by the presence of an N-terminal 27 amino acid leader peptide present on the mitochondrial form [29,13]. Both Gpx4 forms were detected in testis, but in brain only the cytosolic form was seen. Gpx4 was not upregulated in any tissues from Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) mice relative to controls (data not shown), in agreement with previous reports that other antioxidant protein activities are not affected by the lack of Gpx1 [10].

Fig. 5.

Western blot analysis of Gpx1 expression in 129B6-Gpx1tm1Mgr mice. (A) Western analysis of Gpx1 in tissue lysates from wild type (+/+) animals and isolated mitochondria (M) from (+/+) or 129/B6Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) animals. Expression was detected with antisera raised against Gpx1, and the 22 kDa monomer is indicated. Li = liver, Ht = heart, Ki = kidney. (B) Western analysis of Gpx4 in tissue lysates from wild type and 129B6-Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) animals. Expression was detected with antisera raised against Gpx4. The L indicates the 23 kDa, “long” form including the mitochondrial leader peptide and the S indicates the 20 kDa “short” form, minus the leader peptide [28,29]. Br = brain, Ts = testis.

To determine if Gpx1 was localized to the mitochondria in tissues that express the highest levels of Gpx1, Western analysis was performed on isolated mitochondria. In normal animals, Gpx1 was detected at very high levels in the mitochondria from liver and kidney, but very little was detected in the mitochondria from heart. As expected, in Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) animals, there was a total absence of Gpx1 expression in mitochondrial (Fig. 5A) as well as tissue lysates (data not shown) from all of the tissues examined (liver, kidney, heart, skeletal muscle, and brain). Hence, the Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) mice are null for Gpx1 protein.

To confirm that Gpx1 is the only mitochondrial Gpx in mouse liver [30], total Gpx activity was measured in isolated mitochondria from wild type and Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) mice. In liver mitochondria, the H2O2-reducing Gpx activity of the Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) mice is less than 1.5 % that of wild type control mitochondria (13820 mU/mg). No Gpx activity was detected in heart mitochondria from wild type or Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) mutant mice. These results support the hypothesis that Gpx1 plays an important role in protection against oxidative stress in liver but not in heart mitochondria.

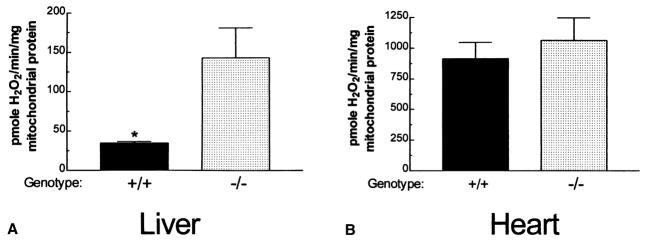

Our studies have confirmed that Gpx1 is both a cytosolic and mitochondrial enzyme, and that it is the primary Gpx in most tissues. Therefore, we predicted that mitochondria isolated from tissues with the highest mitochondrial Gpx1 would have the highest rate of mitochondrial H2O2 release in the Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) mouse. To test this prediction, we isolated mitochondria from the liver and heart of 5–6 month old Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) and control mice and measured their rates of H2O2 release. The liver mitochondria of Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) mice released H2O2 at approximately four times the rate of liver mitochondria from normal mice (Fig. 6A). This confirms that Gpx1 plays a major role in H2O2 detoxification in liver mitochondria.

Fig. 6.

H2O2 release in 129-Gpx1tm1Mgr mouse liver and heart. The bars represent the mean±SEM level of H2O2 release for mitochondria from normal (+/+) and 129-Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) liver (A) and heart (B). p < .05 for normal (+/+) as compared with (−/−) mitochondria for the same tissue; n = 4 for each group.

By contrast, H2O2 release from the heart mitochondria of Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) mice was not increased relative to control mitochondria (Fig. 6B). Hence, Gpx1 is not a major factor in protecting heart mitochondria against oxidative stress, consistent with its absence in heart mitochondrial preparations.

To assess the effect of Gpx1-deficiency on the formation of lipid peroxides, a method for the direct detection of lipid hydroperoxides was utilized. For total organellar extracts from liver, the levels of lipid hydroperoxides were approximately 60% greater (p < .01) in 14–16 month old Gpx1tm1Mgr −/− (9.1 ± 0.8 μM, n = 6) vs. +/+ (5.6 ± 0.8 μM, n = 6) mice. Thus, Gpx1 plays a significant role in minimizing oxidative damage to lipids in liver, perhaps through its detoxification of H2O2 in this tissue.

By contrast, the levels of lipid peroxides extracted from liver mitochondria were not significantly different in the Gpx1tm1Mgr −/− (24.7 ± 1.0 μM, n = 6) and +/+ (23.8 ±1.0 μM, n = 6) mice. This result suggests that the relatively stable H2O2 causes damage that extends beyond its major site of production in the mitochondria to a broad range of cellular components.

Similarly, for heart mitochondria the levels of lipid hydroperoxides were not significantly different in the Gpx1tm1Mgr −/− (33.5 ± 3 nM, n = 3) and +/+ mice (42.3 ± 5 nM, n = 4), consistent with the similar rates of heart mitochondrial H2O2 efflux between both groups.

To assess the specific effect of Gpx1-deficiency on the ATP-generating capacity of mitochondrial OXPHOS, the respiration rates were measured on mitochondria isolated from liver and heart of 8–10 month old Gpx1tm1Mgr −/−and +/+ animals. For heart mitochondria, the RCR, the “power output” (a measure of maximal ATP production rate [31,32]), the state III (ADP-stimulated) and state IV (ADP-limited) respiration rates were essentially identical in the Gpx1tm1Mgr −/− and +/+ mice (Table 1). By contrast, in liver mitochondria, the RCR of Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) mitochondria and the “power output” were both reduced by about one-third, relative to control mitochondria (Table 1). Presumably, this reflects the slightly lower state 3 respiration and slightly higher state 4 respiration rates of the liver mitochondria of Gpx1tm1Mgr −/− mice relative to +/+ mice, although these individual differences were not statistically significant. Thus, loss of functional Gpx1 genes had no effect on ATP production in heart, but reduced mitochondrial ATP production in the liver, consistent with the Gpx1 expression profile of these organs.

Table 1.

Respiration of Isolated Mitochondria From Wild Type and 129B6-Gpx1tmlMgr (−/−) Mice

| Liver |

Heart |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | Gpx1tmlMgr (−/−) | Wild type | GpxtmlMgr (−/−) | |

| State IIIa | 44.4 ± 3.5 | 35.8 ± 2.7 | 122 ± 13.4 | 123 ± 19.0 |

| State IVa | 14.8 ± 1.0 | 17.5 ± 2.4 | 31.0 ± 2.5 | 29.0 ± 1.3 |

| RCRb | 3.1 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.2* | 4.0 ± 0.4 | 4.3 ± 0.7 |

| P/Oc | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 2.5 ± 0.3 |

| Power outputd | 4.95 ± 0.51 | 3.40 ± 0.24* | 13.6 ± 1.5 | 11.2 ± 2.1 |

Results are reported as the mean ± SEM.

State III and IV rates are shown as ng atom O/min/mg mitochondrial protein.

The respiratory control ratio (RCR) is the ratio of state III to subsequent state IV rates.

The P/O ratio is the ratio of ADP molecules phosphorylated to oxygen atoms reduced.

The power output is the product of the state III rate and the P/O ratio and represents the (ATPs produced) (mg mitochondrial protein) (min−1)(10−15).

p < .05 for 129B6Gpx1tmlMgr(−/−) compared with wild type controls.

The increased oxidative stress in liver mitochondria from Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) animals might be expected to increase the proton permeability of the mitochondrial inner membrane and thus decrease ΔΨ. To test this possibility, we measured the ΔΨ (Δp = ΔΨ + ΔpH) in 8–10 month old wild type and Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) mice. Surprisingly, ΔΨ values of mitochondria from Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) mice were indistinguishable from those of wild type controls (Table 2). This could either indicate that there is no gross disruption of mitochondrial membrane integrity in Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) mice, or that the respiratory chain is able to compensate for an increased proton leak by increased proton pumping, for example increased state 4 respiration.

Table 2.

Membrane Potential and Ca+2 Capacity of Isolated Liver Mitochondria from 129-Gpx1tmlMgr Mice

| Substrate alone |

Oligomycin + ADP |

CATR + ADP |

CyclosporinA |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | Gpx1tmlMgr (−/−) | Wild type | Gpx1tmlMgr (−/−) | Wild type | Gpx1tmlMgr (−/−) | Wild type | Gpx1tmlMgr (−/−) | |

| ΔΨ | −177 ± 4 | −177 ± 3 | −177 ± 2 | −175 ± 5 | −174 ± 4 | −173 ± 3 | −165 ± 4 | −171 ± 3 |

| Ca+2 capacity | 86 ± 9 | 77 ± 7 | 470 ± 60 | 523 ± 109 | 163 ± 26 | 190 ± 33 | 760 ± 114 | 640 ± 54 |

Membrane potential ΔΨ is presented in mV. The Ca+2 required to open the mitochondrial permeability transition pore is presented in nmole Ca+2/mg mitochondrial protein. Results are reported as the mean ± SEM. CATR = carboxyatractyloside; n = 5 to 7 for each group.

Increased oxidative stress may also act on the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) to increase the probability of opening the pore and initiation of apoptosis [33–36]. Besides oxidative stress, the mtPTP can also be induced by increased Ca+2.

To determine if the liver mitochondria of Gpx1-deficient mice are more prone to activation of the mtPTP, we measured the concentration of exogenous Ca+2 that was required to initiate the collapse of ΔΨ. Surprisingly, there was no significant difference in the Ca+2 level necessary to collapse ΔΨ in liver mitochondria from wild type and Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) mice. Moreover, the addition of cyclosporin A, an inhibitor of the opening of the mtPTP, increased the Ca+2 required to open the mtPTP equally, about 8-fold, in both groups of animals (Table 2). Furthermore, the responses to ADP, a mtPTP inhibitor, and carboxyatractyloside, a mtPTP activator, were similar in both wild type and mutant liver mitochondria (Table 2). These results indicate that the mPTP in liver mitochondria from Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) mice is not altered in its properties, despite exposure to increased oxidative stress.

DISCUSSION

Mitochondria are the major source of cellular energy, generate much of the cellular ROS as a toxic by-product, and are the initiators of programmed cell death [37,38]. As a result, defects in the mitochondrial ability to detoxify H2O2 might be expected to adversely affect mitochondrial bioenergetics. This hypothesis was tested by generating mice lacking the mitochondrial glutathione peroxidase, which is shown here to be the primary selenium-containing, glutathione-dependent, peroxidase in liver mitochondria. Mice lacking Gpx1 display a growth deficiency evident by 8 months of age. Moreover, livers from Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) mice have increased levels of lipid peroxides and isolated liver mitochondria from Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) mice have increased rates of H2O2 production, reduced mitochondrial respiratory control ratio, and decreased mitochondrial power output index.

Tissues in which the Gpx1-deficiency would be expected to affect mitochondrial function should be those that express Gpx1 and in which Gpx1 is incorporated into the mitochondria. The expression patterns of the Gpx isoforms has been unclear up to now [39,40]. We have addressed this issue by raising antibodies to oligopeptides derived from regions of Gpx1 and Gpx4 that are unique to these isoforms. These isoform-specific antibodies were used to demonstrate that Gpx1 is expressed in a variety of tissues with the greatest levels of expression in liver and kidney. By contrast, Gpx4 is expressed at highest levels in testis and brain, but not in liver and kidney.

Our studies confirm and extend previous studies indicating that liver is highly dependent on Gpx1 for its mitochondrial antioxidant defenses [30]. First, there is very little residual Gpx activity in liver mitochondria isolated from Gpx1 (−/−) mice (see results and [10,30]). Second, Gpx2 and Gpx3, two other selenium-dependent, glutathione-utilizing, peroxidases have a very limited expression pattern and are not found in liver or mitochondria [40–42]. Third, Gpx4, which protects mitochondria from oxidative stress in cultured cells [12], was not detected in liver (data not shown). Fourth, catalase is localized to peroxisomes in all tissues except heart, where it is also found in mitochondria [43]. Finally, the activity of mammalian mitochondrial peroxiredoxin (PrxIII), which exhibits thioredoxin-dependent peroxidase activity, is low relative to Gpx activity in liver [44].

A respiratory defect in mitochondria from the Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) liver mitochondria relative to controls was observed. Therefore, Gpx1 is important in maintaining OXPHOS in liver. In properly functioning mitochondria, the energy is stored in the proton gradient which is coupled to ATP synthesis by the ATP synthase. The lower RCRs in the Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) liver mitochondria, relative to controls, may be the result of a reduced electron flux through the electron transport chain and associated reduced proton pumping in the presence of ADP (state 3 conditions), an increased proton leak through the inner mitochondrial membrane in the absence of ADP (state 4conditions), or both. The 30% decrease in RCRs seen in liver mitochondria from Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) mice, relative to controls, is similar to the 30–40% decrease in RCRs seen in the mitochondria isolated from livers of Sod2 heterozygous (+/−) mice [7]. However, in the Sod2 (+/−) mice, the decrease in RCR appears to be the result of a decrease in state 3 respiration, which is likely to be a product of the 30% decrease in complex 1 activity [7].

In the Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) liver mitochondria, the decreased RCRs did not correspond to a reduction in ΔΨ values (Table 2). This indicates that the oxidative stress caused by the Gpx1-deficiency was not sufficient to uncouple OXPHOS, only to increase proton leak. Because the reduced RCR appears to be the product of both decreased state 3 and increased state 4 rates in the Gpx1-deficient mice, H2O2 may have a broader toxic effect on mitochondria than O2•-. Surprisingly, the mitochondria from Gpx1tm1Mgr (−/−) liver did not exhibit an increased tendency to undergo the mitochondrial permeability transition, despite higher levels of H2O2 production. This implies that the elevated H2O2 levels were insufficient to have activated the mtPTP. This might be explained because peroxides appear to mediate their effect on the mtPTP through modulation of the ratios of reduced to oxidized glutathione (GSH/GSSG) [33,45], and the glutathione reductase system may be sufficient to buffer the increased H2O2 levels.

It was also surprising that although lipid peroxides in total liver extracts were increased in Gpx1-deficient mice relative to controls, this difference was not seen in isolated mitochondria from these same tissues. This shows that H2O2 can exert its effects outside of the mitochondria and suggests that mitochondrial proteins (for example OXPHOS components) may be more susceptible than lipids to oxidant–induced damage [6].

In conclusion, the absence of Gpx1 has been shown to cause a reduction in body weights in adult animals. This has been correlated with increased lipid peroxidation and mitochondrial production of H2O2 and a reduction in mitochondrial OXPHOS capacity in liver. Heart, however, is not affected, presumably because the absence of Gpx1 is compensated by the presence of other antioxidant enzymes. Presumably, the damage to the liver mitochondrial OXPHOS machinery alters liver metabolism, which in turn contributes to an inhibition of the postdevelopmental growth. Oxidative damage, either as a result of increased ROS production [46], decreased detoxification [47,48], or both, accumulates with age and is believed to contribute significantly to the aging process (reviewed in [49]). Hence, it is possible that the Gpx1-deficiency exacerbates an endogenous age-dependent decline in overall cellular function. The postdevelopmental weight deficit in the Gpx1-deficient mice, relative to controls, supports this hypothesis. Therefore, the Gpx1-deficient mouse provides strong support for the concept that increased mitochondrial oxidative stress can compromise mitochondrial energy production, and this is an important factor in the pathophysiology of mitochondrial disease and aging.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Drs. Simon Melov, Dean Jones, and Julie Andersen for their help and advice in the preparation of this study. This work was supported by National Institues of Health grants HD36437 (G.R.M.), AG13154, NS21328, HL45572, HL64017 (D.C.W.).

ABBREVIATIONS

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- OXPHOS

oxidative phosphorylation

- Gpx1

gluatathione peroxidase isoform-1

- Sod2

superoxide dismutase isoform-2

- RCR

respiratory control ratio

- mPTP

mitochondrial permeability transition pore

- GSH

reduced glutathione

- GSSG

oxidized glutathione disulfide

- Gpx4

glutathione peroxidase isoform-4

- ES cells

embryonic stem cells

- PHPA

para-hyrodoxyphenylacetate

- ΔΨ

mitochondrial membrane potential

- TPP+

tetraphenylphosphonium

- X-Gal

5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoyl-β-D-galactoside

- NADPH

reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- BSA

Bovine serum albumin

- MOPS

3-(N-morpholino) propane sulfonic acid

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- EGTA

ethylene glycol-bis (2-aminoethyl)-N,N,N′N′-tetraacetic acid

References

- 1.Fontaine E, Eriksson O, Ichas F, Bernardi P. Regulation of the pereability transition pore in skeletal muscle mitochondria. Modulation by electron flow through the respiratory chain complex I. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12662–12668. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chance B, Sies H, Boveris A. Hydroperoxide metabolism in mammalian organs. Physiol Rev. 1979;59:527–605. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beyer W, Imlay J, Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutases. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1991;40:221–53. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60843-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ursini F, Maiorino M, Brigelius-Flohe R, Aumann KD, Roveri A, Schomburg D, Flohe L. Diversity of glutathione peroxidases. Meth Enzymol. 1995;252:38–53. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)52007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melov S, Coskun P, Patel M, Tuinstra R, Cottrell B, Jun AS, Zastawny TH, Dizdaroglu M, Goodman SI, Huang TT, Miziorko H, Epstein CJ, Wallace DC. Mitochondrial disease in superoxide dismutase 2 mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:846–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Y, Huang TT, Carlson EJ, Melov S, Ursell PC, Olson JL, Noble LJ, Yoshimura MP, Berger C, Chan PH. Dilated cardiomyopathy and neonatal lethality in mutant mice lacking manganese superoxide dismutase. Nat Genet. 1995;11:376–81. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams MD, VanRemmen H, Conrad CC, Huang TT, Epstein CJ, Richardson A. Increase oxidative damage is correlated to altered mitochondrial function in heterozygous manganese superoxide dismutase knockout mice. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28510–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.28510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zoratti M, Szabo I. The mitochondrial permeability transition (review) Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1241:139–76. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(95)00003-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldstein S, Meyerstein D, Czapski G. The Fenton Reagents. Free Radic Biol Med. 1993;15:435–45. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(93)90043-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho YS, Magnenat JL, Bronson RT, Cao J, Gargano M, Sugawara M, Funk CD. Mice deficient in cellular glutathione peroxidase develop normally and show no increased sensitivity to hyperoxia. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16644–16651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Haan JB, Bladier C, Griffiths P, Kelner M, O’Shea RD, Cheung NS, Bronson RT, Silvestro MJ, Wild S, Zheng SS, Beart PM, Hertzog PJ, Kola I. Mice with a homozygous null mutation for the most abundant glutathione peroxidase, Gpx1, show increased susceptibility to the oxidative stress-inducing agents paraquat and hydrogen peroxide. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:22528–22536. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arai M, Imai H, Koumura T, Yoshida M, Emoto K, Umeda M, Chiba N, Nakagawa Y. Mitochondrial phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase plays a major role in preventing oxidative injury to cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4924–4933. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.4924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pushpa-Rekha TR, Burdsall AL, Oleksa LM, Chisolm GM, Driscoll DM. Rat phospholipid-hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase. cDNA cloning and identification of multiple transcription and translation start sites. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26993–26999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chambers I, Frampton J, Goldfarb P, Affara N, McBain W, Harrison PR. The structure of the mouse glutathione peroxidase gene: the selenocysteine in the active site is encoded by the ’termination’ codon, TGA. Embo J. 1986;5:1221–1227. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04350.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacGregor GR, Zambrowicz BP, Soriano P. Tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase is expressed in both embryonic and extraembryonic lineages during mouse embryogenesis but is not required for migration of primordial germ cells. Development. 1995;121:1487–86. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.5.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soriano P, Montgomery C, Geske R, Bradley A. Targeted disruption of the c-src proto-oncogene leads to osteopetrosis in mice. Cell. 1991;64:693–702. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90499-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramirez-Solis R, Davis AC, Bradley A. In: Guide to techniques in mouse development. Wassarman PM, DePamphilis ML, editors. San Diego: Academic Press; 1993. pp. 855–878. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart CL. In: Guide to techniques in mouse development. Wassarman PM, DePamphilis ML, editors. San Diego: Academic Press; 1993. pp. 823–855. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trounce IA, Kim YL, Jun AS, Wallace DC. Assessment of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in patient muscle biopsies, lymphoblasts, and transmitochondrial cell lines. Meth Enzymol. 1996;264:484–509. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)64044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esposito LA, Melov S, Panov A, Cottrell BA, Wallace DC. Mitochondrial disease in mouse results in increased oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;98:4820–4825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hyslop PA, Sklar LA. A quantitative fluorimetric assay for the determination of oxidant production by polymorphonuclear leukocytes: its use in the simultaneous fluorimetric assay of cellular activation processes. Analytical Biochem. 1984;141:280–286. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90457-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwong LK, Sohal RS. Substrate and site specificity of hydrogen peroxide generation in mouse mitochondria. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;350:118–26. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Demura M, Kamo N, Kobatake Y. Mitochondrial membrane potential estimated with the correction of probe binding. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987;894:355–64. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(87)90113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamo N, Muratsugu M, Hongoh R, Kobatake Y. Membrane potential of mitochondria measured with an electrode sensitive to tetraphenyl phosphonium and relationship between proton electrochemical potential and phosphorylation potential in steady state. J Membr Biol. 1979;49:105–21. doi: 10.1007/BF01868720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rottenberg H. Membrane potential and surface potential in mitochondria: Uptake and binding of lipophilic cations. J Membr Biol. 1984;81:127–38. doi: 10.1007/BF01868977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LaNoue KF, Jeffries FM, Radda GK. Kinetic control of mitochondrial ATP synthesis. Biochemistry. 1986;25:7667–7675. doi: 10.1021/bi00371a058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedrich G, Soriano P. Promoter traps in embryonic stem cells: a genetic screen to identify and mutate developmental genes in mice. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1513–23. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.9.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Godeas C, Sandri G, Panfili E. Distribution of phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase (PHGPx) in rat testis mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1191:147–150. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(94)90242-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arai M, Imai H, Sumi D, Imanaka T, Takano T, Chiba N, Nakagawa Y. Import into mitochondria of phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase requires a leader sequence. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;227:433–9. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Esworthy RS, Swiderek KM, Ho YS, Chu FF. Selenium-dependent glutathione peroxidase-GI is a major glutathione peroxidase activity in the mucosal epithelium of rodent intestine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1381:213–26. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(98)00032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villani G, Attardi G. In vivo control of respiration by cytochrome c oxidase in wild-type and mitochondrial DNA mutation-carrying human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1166–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Villani G, Tattoli M, Capitanio N, Glaser P, Papa S, Danchin A. Functional analysis of subunits III and IV of Bacillus subtilis aa3-600 quinol oxidase by in vitro mutagenesis and gene replacement. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1232:67–74. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(95)00112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chernyak BV, Bernardi P. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore is modulated by oxidative agents through both pyridine nucleotides and glutathione at two separate sites. Eur J Biochem. 1996;238:623–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0623w.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Connern CP, Halestrap AP. Recruitment of mitochondrial cyclophilin to the mitochondrial inner membrane under conditions of oxidative stress that enhance the opening of a calcium-sensitive non-specific channel. Biochem J. 1994;302:321–4. doi: 10.1042/bj3020321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Halestrap AP, Woodfield KY, Connern CP. Oxidative stress, thiol reagents, and membrane potential modulate the mitochondrial permeability transition by affecting nucleotide binding to the adenine nucleotide translocase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3346–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kroemer G, Zamzami N, Susin SA. Mitochondrial control of apoptosis. Immunol Today. 1997;18:44–51. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)80014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marzo I, Brenner C, Zamzami N, Jurgensmeier JM, Susin SA, Vieira HL, Prevost MC, Xie Z, Matsuyama S, Reed JC, Kroemer G. Bax and adenine nucleotide translocator cooperate in the mitochondrial control of apoptosis. Science. 1998;281:2027–2031. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5385.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wallace DC. Mitochondrial disease in mouse and man. Science. 1999;283:1482–1488. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5407.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oberley TD, Oberley LW, Slattery AF, Elwell JH. Immunohistochemical localization of glutathione-S-transferase and glutathione peroxidase in adult Syrian hamster tissues and during kidney development. Am J Pathol. 1991;139:355–369. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trepanier G, Furling D, Puymirat J, Mirault ME. Immuno-cytochemical localization of seleno-glutathione peroxidase in the adult mouse brain. Neuroscience. 1996;75:231–43. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00222-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Esworthy RS, Swiderek KM, Ho YS, Chu FF. Selenium-dependent glutathione peroxidase-GI is a major glutathione peroxidase activity in the mucosal epithelium of rodent intestine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1381:213–226. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(98)00032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maser RL, Magenheimer BS, Calvet JP. Mouse plasma glutathione peroxidase. cDNA sequence analysis and renal proximal tubular expression and secretion. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:27066–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Radi R, Turrens JF, Chang LY, Bush KM, Crapo JD, Freeman BA. Detection of catalase in rat heart mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:22028–2234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kang SW, Chae HZ, Seo MS, Kim K, Baines IC, Rhee SG. Mammalian peroxiredoxin isoforms can reduce hydrogen peroxide generated in response to growth factors and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6297–6302. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.11.6297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Costantini P, Chernyak BV, Petronilli V, Bernardi P. Modulation of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore by pyridine nucleotides and dithiol oxidation at two separate sites. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6746–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.6746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sohal RS, Ku H-H, Agarwal S, Forster MJ, Lal H. Oxidative damage, mitochondrial oxidant generation and antioxidant defenses during aging and in response to food restriction in the mouse. Mech Aging Dev. 1994;74:21–133. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(94)90104-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tian L, Cai Q, Wei H. Alterations of antioxidant enzymes and oxidative damage to macromolecules in different organs of rats during aging. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998;24:1477–1484. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cristiano F, de Haan JB, Ianello RC, Kola I. Changes in the levels of enzymes which modulate the antioxidant balance occur during aging and correlate with cellular damage. Mech Aging Dev. 1995;80:93–105. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(94)01561-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beckman KB, Ames BN. The free radical theory of aging matures (review) Physiol Rev. 1998;78:547–581. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.2.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]