Abstract

Accurate neural crest cell (NCC) migration requires tight control of cell adhesions, cytoskeletal dynamics and cell motility. Cadherins and RhoGTPases are critical molecular players that regulate adhesions and motility during initial delamination of NCCs from the neuroepithelium. Recent studies have revealed multiple functions for these molecules and suggest a precise balance of their activity is crucial. RhoGTPase appears to regulate both cell adhesions and protrusive forces during NCC delamination. Increasing evidence shows that cadherins are multi-functional proteins with novel, adhesion-independent signaling functions that control NCC motility during both delamination and migration. These functions are often regulated by specific proteolytic cleavage of cadherins. After NCC delamination, planar cell polarity signaling acts via RhoGTPases to control NCC protrusions and migration direction.

Introduction

Neural crest cells (NCCs) give rise to several tissues, including neurons and glia of the peripheral nervous system, craniofacial structures and pigment cells [1]. NCCs are characterized by the remarkable abilities to undergo an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), in which they delaminate from the neuroepithelium and become migratory, and then to navigate specific migration pathways to their targets. Precise regulation of cell-cell adhesions and cytoskeletal dynamics is critical for these migratory abilities. Recent research has identified several important molecular signals regulating NCC motility, including: 1) the Rho family of small GTPases, which are key regulators of cytoskeletal dynamics, cell adhesions, and cell motility [2,3]; 2) Cadherins, which are calcium dependent homophilic cell adhesion molecules with numerous functions in morphogenesis and neural development [4,5], and which interact extensively with RhoGTPases [6,7]; and 3) planar cell polarity (PCP) signaling, which was first identified as a molecular pathway defining cell polarity, and more recently has been shown to have central roles in cell migration [8,9].

In this review we focus on recent studies that provide new insights into the specific functions of these molecular signals during the initial stages of NCC migration. In particular, we discuss the roles of RhoGTPase in regulating NCC motility during EMT, novel adhesion-independent functions for cadherins in NCC EMT and migration, and new functions for PCP signaling in regulating RhoGTPases and causing polarized migration of NCCs.

NCC motility during EMT and the role of RhoGTPase

While the structure of the neuroepithelium is maintained through cell-cell adhesions, it is also a remarkably dynamic tissue with continual cell movements and turnover of adhesions [10–12]. Cell bodies move to the apical surface to undergo mitosis, and NCCs move to the basal surface before EMT (Figure 1). Cell adhesions and motility must be tightly regulated so that only NCCs and not other neuroepithelial cells become migratory. A full understanding of mechanisms controlling cell motility in this complex tissue requires analysis of cell behavior in the natural, three-dimensional environment [13]. Two recent studies have demonstrated the ability to image behaviors of NCCs during EMT in situ [14•,15•]. Imaging within chick trunk slices showed that premigratory NCCs retract their apical neuroepithelial attachments prior to EMT, and usually the molecular components of apical adherens junctions are downregulated before retraction [14•]. However, occasionally NCCs retract apical attachments with junctional components still present, or cells can shear and leave junctional remnants at the apical surface. These observations suggest apical retraction may not simply be a passive process resulting from adhesion loss, but rather an active process requiring contractile forces. Indeed, imaging of NCC EMT in the intact zebrafish hindbrain showed that premigratory NCCs round up at the basal edge of the neuroepithelium while extending membrane bleb protrusions that require myosin II activity [15•]. Interestingly, inhibition of myosin II also reduced the number of NCCs undergoing EMT, suggesting an association between blebbing and migration. Consistent with this idea, membrane bleb-based motility provides the protrusive force behind cell migration in several other cell types [16–19]. Together, these imaging studies suggest that both loss of cell adhesion and myosin-based contractile forces initiate NCC motility within the neuroepithelium, and they lay the groundwork for further elucidation of molecular mechanisms.

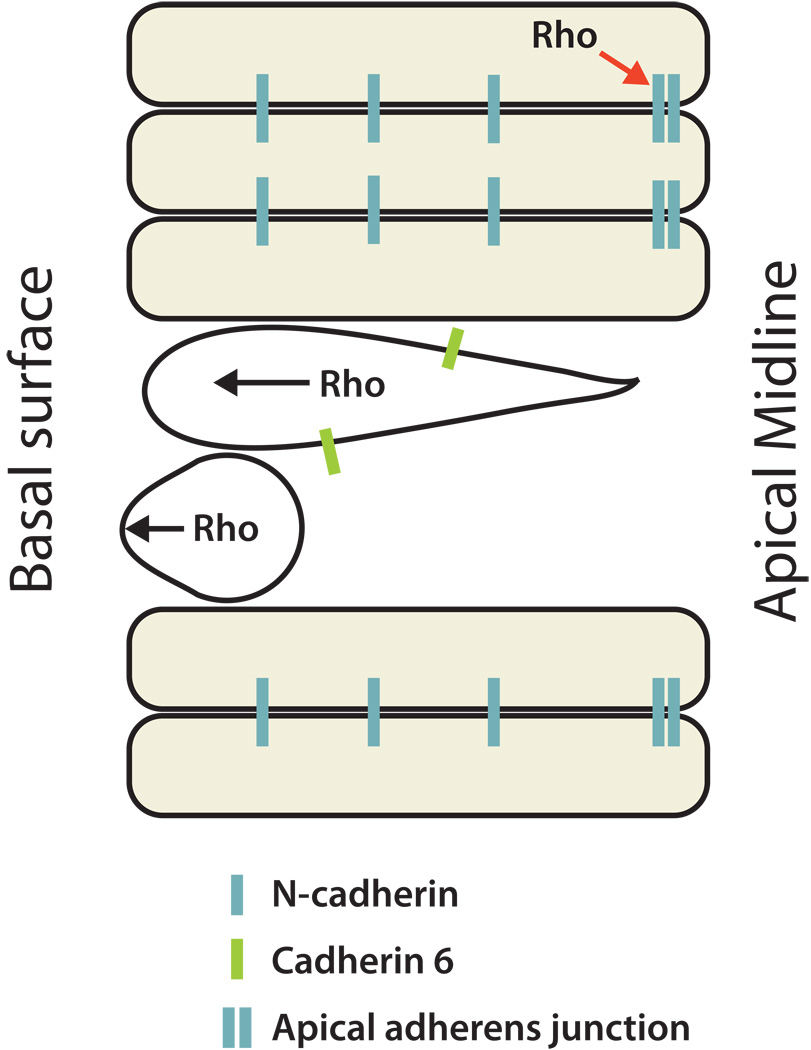

Figure 1. Potential cellular events regulated by Rho activity during NCC EMT.

Schematic dorsal view of one side of the neuroepithelium with apical midline and basal surface indicated. Neuroepithelial cells (yellow shaded) span the apical to basal surfaces and have N-cadherin mediated adhesions with one another. Pre-migratory NCCs (white) express Cad6, lose their apical attachments, become rounded at the basal surface and display membrane blebbing before EMT. Rho can both maintain adhesions in the neuroepithelium (red arrow) and drive contractile forces involved in apical retraction and membrane blebbing (black arrows).

Prime candidates for controlling these events are the RhoGTPases. However, recent studies have given conflicting results regarding the role of Rho in NCC EMT. Rho was first implicated in NCC EMT by experiments showing it was required for NCC emigration from chick trunk explants [20]. Further support for a positive function of Rho in EMT comes from live imaging of zebrafish cranial NCCs in vivo [15•]. Inhibition of Rho kinase (ROCK), a downstream effector of Rho, caused a reduction in blebbing and EMT, suggesting Rho/ROCK signaling may drive the motile forces underlying EMT. In contrast, another study found that ROCK promotes neuroepithelial integrity by stabilizing N-cadherin, and inhibition of Rho or ROCK caused EMT in the chick trunk [21•]. One potential explanation for these conflicting results is that Rho has different functions depending on the particular time and location of its activation within the cell, and thus subtle differences in experimental approach could cause variable outcomes. For example, the two ROCK inhibitors used in these studies have different potencies [22]. A potential model is that higher active Rho levels induce contractile forces and EMT, while lower levels maintain cell adhesions (Figure 1). In this case, the stronger inhibitor [21•] might affect cell adhesions broadly and cause ectopic EMT, while the less potent inhibitor [15•] might only block motile behaviors underlying EMT, leaving neuroepithelial adhesions unaffected. The conflicting results could also be due to differences in species, embryos preparation (intact embryos vs. explants) or axial levels examined. However, two studies using chick trunk explants [20,21•] but different Rho inhibitors reached opposite conclusions, suggesting the degree or timing of Rho inhibition is critical to experimental outcome. Overall, these studies suggest a precise spatiotemporal balance of Rho activity is essential for controlling EMT, and that Rho may have multiple functions within NCCs.

Cadherins in EMT and migration

Changes in expression from one cadherin to another (“cadherin switching”) is a hallmark of EMTs in general and appears to be critical for cells to acquire the motile phenotype [7]. While some cadherins are downregulated before the onset of motility, others are upregulated in migrating cells, suggesting they may promote migration. The function of cadherin switching and the specific roles of each cadherin in various EMTs are not yet clear, however increasing evidence suggests cadherins have diverse functions in NCC motility, including novel adhesion-independent functions in addition to cell adhesion roles.

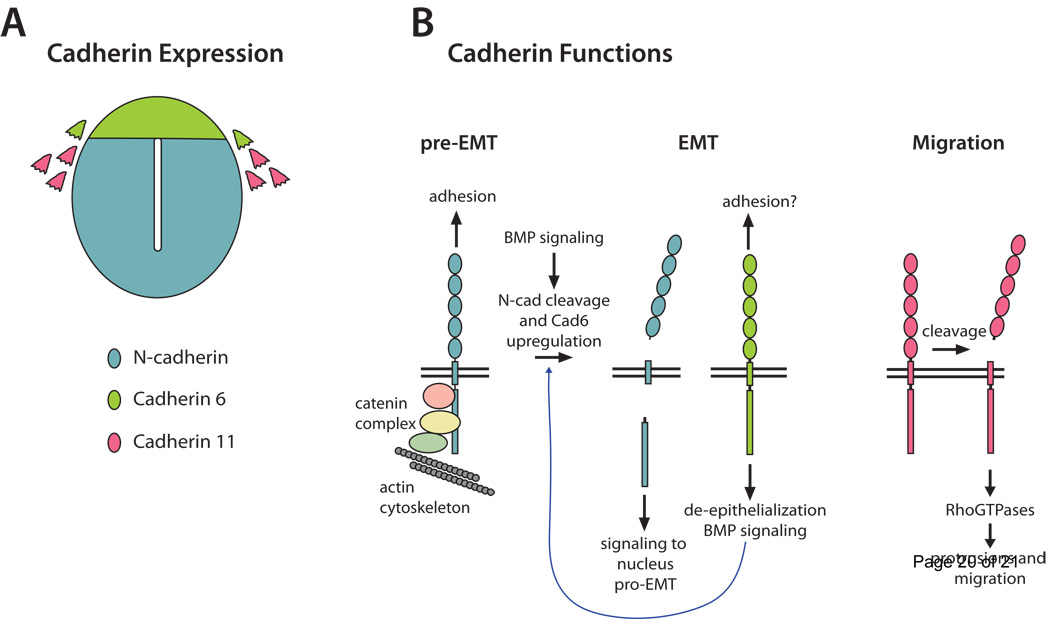

N-cadherin (N-cad) is broadly expressed in the neuroepithelium, but is downregulated in NCCs before EMT [23,24] (Figure 2). Cadherin 6B (Cad6B) is expressed dynamically, first in premigratory NCCs before EMT, then for a short time after delamination, and later is downregulated in migratory NCCs [23–25••]. Cadherin 11 (Cad11) is expressed in migratory NCCs [26,27]. In the avian trunk, BMP signaling initiates EMT [28,29] and causes downregulation of N-cad protein in premigratory NCCs [30], which reduces adhesions in the neuroepithelium. However, it is not simply the loss of N-cad mediated adhesion that causes EMT. BMP also stimulates proteolytic cleavage of N-cad, releasing a cytoplasmic fragment of N-cad that transports to the nucleus and stimulates expression of other EMT-promoting genes [30]. Thus N-cad is multifunctional, and BMP signaling transforms it from a full-length adhesive molecule to a pro-EMT signaling molecule (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Cadherin expression and functions.

A) Schematic cross section of neural tube illustrating cadherin expression patterns. Color key indicates cadherin identity for both A and B. B) Functions of cadherins. Before EMT and in neuroepithelial cells, full length N-cad mediates homophilic adhesion between cells and is anchored to the actin cytoskeleton via the catenin complex. BMP signaling stimulates N-cad cleavage, reducing adhesion and releasing a cytoplasmic fragment that moves to the nucleus and induces transcription of pro-EMT genes. BMP also upregulates Cad6, which feeds back on BMP signaling (blue curved arrow) and leads to de-epithelialization of pre-migratory NCCs. In migrating NCCs, cleaved Cad11 signals via Rho GTPases to stimulate cell protrusions and migration.

The function of Cad6B in NCC EMT is less clear, both because of its dynamic expression pattern and because of conflicting reports of its function. Cad6B knockdown in the chick midbrain caused premature NCC migration, while overexpression inhibited migration [31], suggesting Cad6B downregulation is important for EMT. Indeed, cad6B transcription is repressed by Snail2, a transcription factor critical for NCC development and EMT [32]. More recently, however, experiments in chick trunk led to the opposite conclusion, that Cad6B promotes EMT [25••], consistent with earlier studies showing BMP upregulates Cad6B [20,29]. In this case, Cad6B knockdown reduced the number of migrating NCCs, while ectopic Cad6B expression disrupted neuroepithelial morphology [25••]. These authors propose Cad6B functions to induce an early, pre-delamination stage of EMT termed “de-epithelialization”, during which premigratory NCCs lose polarity markers and acquire some motile characteristics. Interestingly, Cad6B acts in part by stimulating BMP signaling intracellularly, suggesting a model wherein Cad6B and BMP signaling create a positive feedback loop in premigratory NCCs [25••]. By stimulating BMP signaling, Cad6B could also contribute to EMT by driving N-cad cleavage. Thus Cad6B can have pro-EMT activity and, like N-cad, appears to have signaling functions apart from traditional adhesion roles (Figure 2). The conflicting findings from the two Cad6B functional studies may reflect a difference in the predominance of adhesive versus signaling functions between cranial and trunk NCCs. This would not be surprising given the known molecular differences between cranial and trunk NCCs (e.g. [33]).

Recent work investigating the function of Cad11, which is upregulated in migratory NCCs (Figure 2), has revealed another means by which a cadherin can promote motility. Cad11 is required for cranial NCC migration in Xenopus [34••,35], although its overexpression impairs migration [35,36]. Thus, much like N-Cad in EMT, Cad11 may have antagonistic roles in later NCC migration. In support of this, proteolytic cleavage of the extracellular Cad11 domain, which eliminates adhesive function, is necessary for NCC migration [35] (Figure 2). Live imaging revealed that NCCs fail to form lamellipodia and lose migratory ability following Cad11 knockdown [34••]. Interestingly, these defects were rescued by expression of the membrane anchored cytosolic fragment of Cad11, or by activation of RhoGTPases [34••]. Together these studies suggest a model wherein proteolytic cleavage of Cad11 releases adhesion and allows signaling by the cytoplasmic domain via RhoGTPases to generate protrusions and motility. In this model both loss of adhesion and RhoGTPase modulation could contribute to motility.

On the whole, these studies demonstrate that cadherins are multi-functional molecules with diverse roles in controlling NCC motility beyond traditional adhesive roles. N-cad, Cad6B, and Cad11 all appear to have signaling functions that can generate motility. Several factors, including the dynamics of cadherin trafficking, turnover and cleavage, and the levels of one cadherin relative to another, are all likely crucial for controlling the fine balance between adhesion, signaling and motility.

PCP signaling and Rho GTPases control polarized NCC protrusions during migration

In order to migrate in a directed manner along their pathways, NCCs must be polarized with cell protrusions biased to the leading edge. Recent studies have provided new insight into the mechanisms controlling polarized protrusions in NCCs, and have revealed a combination of signals that converge on the RhoGTPases (Figure 3). Non-canonical Wnt PCP signaling is required for cranial NCC migration [37], and live imaging in zebrafish demonstrated that the key function of Wnt PCP signaling is to restrict lamellipodial protrusions to the NCC leading edge [38•]. Moreover, inhibition of Wnt PCP signaling caused a significant decrease in active Rho. Together these data suggest a model wherein Wnt PCP signaling normally activates Rho and causes retraction of inappropriate protrusions at the NCC trailing edge [38•].

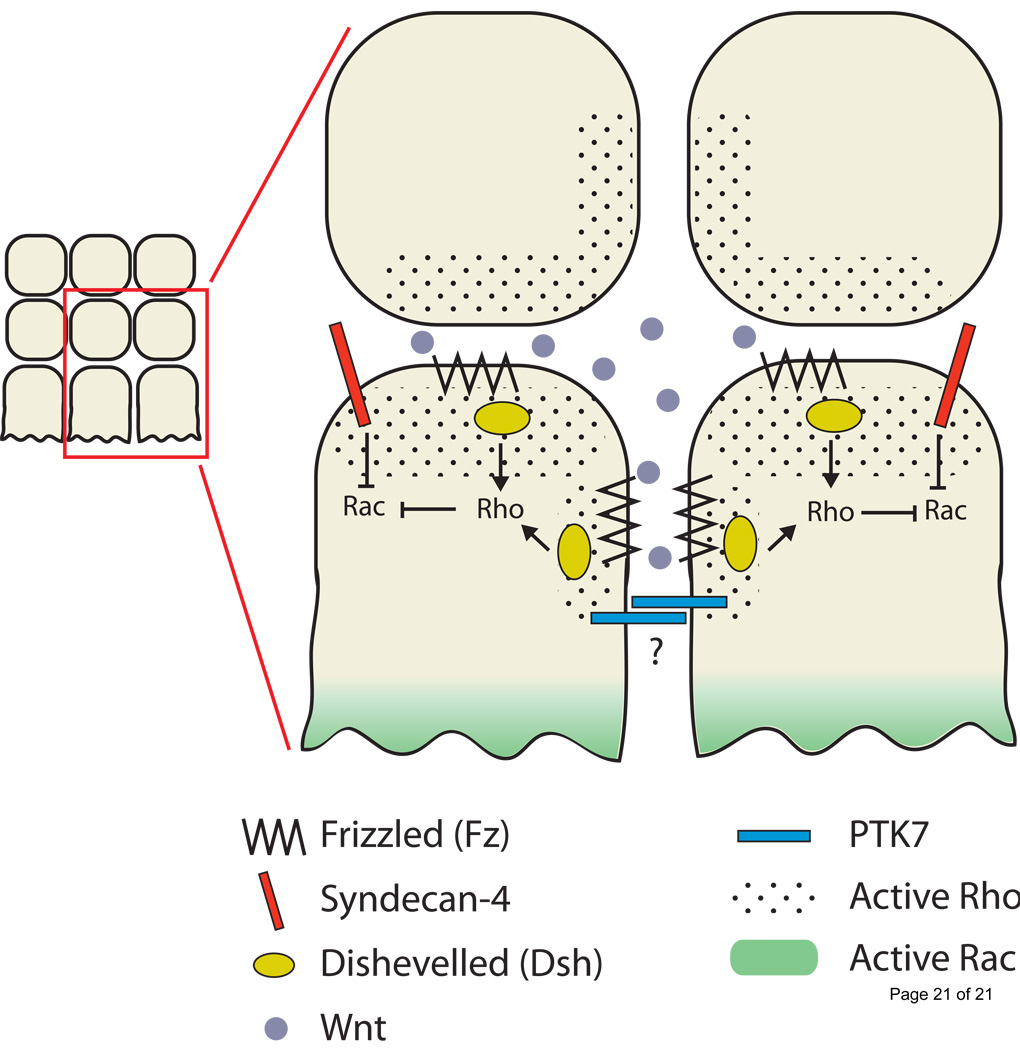

Figure 3. Model of directed migration driven by cell-contact mediated PCP signaling.

Cell contact between NCCs stimulates localization and activation of Fz and Dsh, and local activation of Rho, which inhibits protrusions at trailing and lateral edges of cells migrating in sheets. Syn-4 inhibits Rac activation at the trailing edge, biasing Rac activation and cell protrusion at the leading edge. PTK7 is a potential mediator of cell-cell contact.

A parallel pathway involving Syndecan4 (Syn4) also influences Wnt PCP signaling and Rho activity [38•]. Syn4 is a transmembrane proteogycan expressed in NCCs. Syn4 knockdown reduced the directionality of migrating zebrafish NCCs in vivo, and caused a global increase in active Rac [38•], another Rho-family GTPases typically active at leading edges of migrating cells [2,39]. This study also showed that Rho inhibition caused increased active Rac and randomly directed cell protrusions. Moreover, Wnt PCP and Syn4 interact genetically, suggesting these pathways cooperate to control NCC migration. Together these studies support a model in which Syn4 inhibits Rac while Wnt PCP activates Rho (which also inhibits Rac) at the trailing edge of NCCs (Figure 3). The overall result is increased cell protrusions biased to the leading edge. A key unresolved question in this model, however, is how PCP and Syn4 signaling are specifically activated at the trailing edge of the cells.

One potential means to localize PCP signaling is through cell-cell contact between NCCs. An important recent live imaging study demonstrated that cranial NCCs retract protrusions and change direction upon contact with one another, and that this behavior requires both PCP signaling and Rho-ROCK activity [40••]. The PCP signaling components Frizzled-7 (Fz7) and Disheveled (Dsh), as well as active Rho, become localized to plasma membranes at cell contact points. The authors propose that contact inhibition is a primary mechanism driving directed movement of NCCs migrating in streams (Figure 3), where contact with neighboring NCCs along lateral and trailing edges activates PCP and Rho signaling, inhibiting protrusions in these areas. While contact inhibition is likely a key driving force behind directed migration of cranial NCCs, it undoubtedly acts together with other inhibitory and attractive environmental cues [13]. Whether contact inhibition plays a significant role in trunk NCC migration is not clear. Trunk NCCs often migrate as attached chains [41] and do not show repulsion upon contact with one another in vivo [42].

A critical question that remains unanswered in the contact inhibition model is the identity of cell surface molecules that recognize cell-cell contact and stimulate PCP and Rho activity. One potential candidate is protein tyrosine kinase 7 (PTK7), a transmembrane regulator of PCP signaling recently shown to be required for Xenopus cranial NCC migration [43•]. Interestingly, PTK7 recruits Dsh to the membrane by forming a complex with Fz7. Moreover, PTK7 is an Ig domain family protein and can bind homophilically. Thus a potential model exists wherein cell-cell contact mediated by PTK7 causes clustering of PTK7, Fz and Dsh, and thereby leads to activation of PCP signaling and Rho at sites of cell contact (Figure 3).

Conclusions

Precise levels of RhoGTPase activity and specific cadherins are crucial for determining which cells undergo EMT, and evidence suggests these molecules have multiple functions in NCCs. The conflicting results from different experimental manipulations of Rho/ROCK and Cad6B likely reflect a requirement for tight control of their activity and of their alternative functions during EMT. Activation of Rho in specific subcellular locations or stages may lead to different outcomes depending on the presence of specific modulators or downstream effectors. Determining whether Rho is in fact differentially active during particular subcellular events will require application of techniques that allow imaging active Rho within cells in vivo[19,38]. Moreover, future experiments combining Rho/ROCK manipulation in individual cells with live imaging of cell behavior will help elucidate its functions during specific NCC behaviors. Similarly, Cad6B manipulation combined with live imaging could reveal its role in cell motility and the potential contributions of adhesive versus non-adhesive functions during EMT. Future challenges are to further define the specific functions of each cadherin, how cadherin switching leads to EMT, and how cadherins interact with Rho GTPases and other signaling molecules to orchestrate motile behavior.

During NCC migration, Cad11, PCP signaling, and Syn4 are important signaling pathways by which NCCs respond to environmental cues that affect their motility and migration direction. Contact between NCCs can activate PCP signaling and Rho to inhibit protrusions at trailing edges, although the specific molecules that mediate contact inhibition are yet to be determined. Cad11 also acts via RhoGTPases, although it promotes protrusion formation. Future experiments will be required to determine how PCP and Cad11 signaling may interact with one another and with other extracellular cues that regulate NCC motility and migration pathway.

Acknowledgements

Work in the authors’ laboratory is funded by National Institutes of Health grant NS042228.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Le Douarin N, Kalcheim C. The Neural Crest. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raftopoulou M, Hall A. Cell migration: Rho GTPases lead the way. Dev Biol. 2004;265:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaffe AB, Hall A. Rho GTPases: biochemistry and biology. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:247–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.020604.150721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taneyhill LA. To adhere or not to adhere: the role of Cadherins in neural crest development. Cell Adh Migr. 2008;2:223–230. doi: 10.4161/cam.2.4.6835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gumbiner BM. Regulation of cadherin-mediated adhesion in morphogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:622–634. doi: 10.1038/nrm1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samarin S, Nusrat A. Regulation of epithelial apical junctional complex by Rho family GTPases. Front Biosci. 2009;14:1129–1142. doi: 10.2741/3298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wheelock MJ, Shintani Y, Maeda M, Fukumoto Y, Johnson KR. Cadherin switching. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:727–735. doi: 10.1242/jcs.000455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodrich LV. The plane facts of PCP in the CNS. Neuron. 2008;60:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein TJ, Mlodzik M. Planar cell polarization: an emerging model points in the right direction. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:155–176. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.012704.132806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hong E, Brewster R. N-cadherin is required for the polarized cell behaviors that drive neurulation in the zebrafish. Development. 2006;133:3895–3905. doi: 10.1242/dev.02560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyons DA, Guy AT, Clarke JD. Monitoring neural progenitor fate through multiple rounds of division in an intact vertebrate brain. Development. 2003;130:3427–3436. doi: 10.1242/dev.00569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyata T. Development of three-dimensional architecture of the neuroepithelium: role of pseudostratification and cellular 'community'. Dev Growth Differ. 2008;50 Suppl 1:S105–S112. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2007.00980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clay MR, Halloran MC. Control of neural crest cell behavior and migration: Insights from live imaging. Cell Adh Migr. 2010;4 doi: 10.4161/cam.4.4.12902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ahlstrom JD, Erickson CA. The neural crest epithelial-mesenchymal transition in 4D: a 'tail' of multiple non-obligatory cellular mechanisms. Development. 2009;136:1801–1812. doi: 10.1242/dev.034785. The authors develop an embryonic chick slice culture system that allows 4-D imaging of NCCs undergoing EMT in situ. They show that retraction of apical attachments in the neuroepithelium can occasionally occur without downregulation of apical junction components (e.g. α-catenin), suggesting traction forces can break cell adhesions.

- 15. Berndt JD, Clay MR, Langenberg T, Halloran MC. Rho-kinase and myosin II affect dynamic neural crest cell behaviors during epithelial to mesenchymal transition in vivo. Dev Biol. 2008;324:236–244. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.09.013. The authors use 4-D imaging of NCCs undergoing EMT in intact zebrafish embryos to characterize specific cell behaviors during EMT. They also use an Factin biosensor to visualize cytoskeletal changes during NCC protrusive behavior, and show that ROCK and myosinII are required for NCC blebbing and EMT.

- 16.Blaser H, Reichman-Fried M, Castanon I, Dumstrei K, Marlow FL, Kawakami K, Solnica-Krezel L, Heisenberg CP, Raz E. Migration of zebrafish primordial germ cells: a role for myosin contraction and cytoplasmic flow. Dev Cell. 2006;11:613–627. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fackler OT, Grosse R. Cell motility through plasma membrane blebbing. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:879–884. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200802081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fink RD, Trinkaus JP. Fundulus deep cells: directional migration in response to epithelial wounding. Dev Biol. 1988;129:179–190. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90172-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kardash E, Reichman-Fried M, Maitre JL, Boldajipour B, Papusheva E, Messerschmidt EM, Heisenberg CP, Raz E. A role for Rho GTPases and cell-cell adhesion in single-cell motility in vivo. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:47–53. doi: 10.1038/ncb2003. sup pp 41-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu JP, Jessell TM. A role for rhoB in the delamination of neural crest cells from the dorsal neural tube. Development. 1998;125:5055–5067. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.24.5055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Groysman M, Shoval I, Kalcheim C. A negative modulatory role for rho and rho-associated kinase signaling in delamination of neural crest cells. Neural Dev. 2008;3:27. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-3-27. This study finds a result opposite to ref 15, that Rho/ROCK signaling promotes neuroepithelial adhesions and must be downregulated for EMT in chick trunk NCCs. The authors use pharmacological approaches to inhibit Rho/ROCK and also to activate Rho with lysophosphatidic acid.

- 22.Yarrow JC, Totsukawa G, Charras GT, Mitchison TJ. Screening for cell migration inhibitors via automated microscopy reveals a Rho-kinase inhibitor. Chem Biol. 2005;12:385–395. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakagawa S, Takeichi M. Neural crest cell-cell adhesion controlled by sequential and subpopulation-specific expression of novel cadherins. Development. 1995;121:1321–1332. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.5.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakagawa S, Takeichi M. Neural crest emigration from the neural tube depends on regulated cadherin expression. Development. 1998;125:2963–2971. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.15.2963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Park KS, Gumbiner BM. Cadherin 6B induces BMP signaling and de-epithelialization during the epithelial mesenchymal transition of the neural crest. Development. 2010;137:2691–2701. doi: 10.1242/dev.050096. The authors show that Cad6B can function to promote NCC EMT by inducing “de-epithelialization”, a first step in EMT in which apical adherens junction components are downregulated or redistributed in pre-migratory NCCs. They also use collagen injection into the lumen to show that Cad6B imparts cells with the capability to migrate into the collagen matrix.

- 26.Kimura Y, Matsunami H, Inoue T, Shimamura K, Uchida N, Ueno T, Miyazaki T, Takeichi M. Cadherin-11 expressed in association with mesenchymal morphogenesis in the head, somite, and limb bud of early mouse embryos. Dev Biol. 1995;169:347–358. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vallin J, Girault JM, Thiery JP, Broders F. Xenopus cadherin-11 is expressed in different populations of migrating neural crest cells. Mech Dev. 1998;75:171–174. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burstyn-Cohen T, Stanleigh J, Sela-Donenfeld D, Kalcheim C. Canonical Wnt activity regulates trunk neural crest delamination linking BMP/noggin signaling with G1/S transition. Development. 2004;131:5327–5339. doi: 10.1242/dev.01424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sela-Donenfeld D, Kalcheim C. Regulation of the onset of neural crest migration by coordinated activity of BMP4 and Noggin in the dorsal neural tube. Development. 1999;126:4749–4762. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.21.4749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shoval I, Ludwig A, Kalcheim C. Antagonistic roles of full-length N-cadherin and its soluble BMP cleavage product in neural crest delamination. Development. 2007;134:491–501. doi: 10.1242/dev.02742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coles EG, Taneyhill LA, Bronner-Fraser M. A critical role for Cadherin6B in regulating avian neural crest emigration. Dev Biol. 2007;312:533–544. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.09.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taneyhill LA, Coles EG, Bronner-Fraser M. Snail2 directly represses cadherin6B during epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitions of the neural crest. Development. 2007;134:1481–1490. doi: 10.1242/dev.02834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Theveneau E, Duband JL, Altabef M. Ets-1 confers cranial features on neural crest delamination. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kashef J, Kohler A, Kuriyama S, Alfandari D, Mayor R, Wedlich D. Cadherin-11 regulates protrusive activity in Xenopus cranial neural crest cells upstream of Trio and the small GTPases. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1393–1398. doi: 10.1101/gad.519409. This study reveals a novel function for Cad11 in regulating NCC motility. The authors show that the cytoplasmic domain of Cad11 acts via RhoGTPases to induce lamellipodial protrusions.

- 35.McCusker C, Cousin H, Neuner R, Alfandari D. Extracellular cleavage of cadherin-11 by ADAM metalloproteases is essential for Xenopus cranial neural crest cell migration. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:78–89. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-05-0535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borchers A, David R, Wedlich D. Xenopus cadherin-11 restrains cranial neural crest migration and influences neural crest specification. Development. 2001;128:3049–3060. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.16.3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Calisto J, Araya C, Marchant L, Riaz CF, Mayor R. Essential role of non-canonical Wnt signalling in neural crest migration. Development. 2005;132:2587–2597. doi: 10.1242/dev.01857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Matthews HK, Marchant L, Carmona-Fontaine C, Kuriyama S, Larrain J, Holt MR, Parsons M, Mayor R. Directional migration of neural crest cells in vivo is regulated by Syndecan-4/Rac1 and non-canonical Wnt signaling/RhoA. Development. 2008;135:1771–1780. doi: 10.1242/dev.017350. This study showed that Syn4 controls the orientation of NCC protrusions, inhibits Rac activation, and genetically interacts with Wnt PCP signaling. The authors also use FRET imaging in living cultured NCCs or in fixed cells in vivo to show that Wnt PCP signaling activates Rho.

- 39.Heasman SJ, Ridley AJ. Mammalian Rho GTPases: new insights into their functions from in vivo studies. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:690–701. doi: 10.1038/nrm2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Carmona-Fontaine C, Matthews HK, Kuriyama S, Moreno M, Dunn GA, Parsons M, Stern CD, Mayor R. Contact inhibition of locomotion in vivo controls neural crest directional migration. Nature. 2008;456:957–961. doi: 10.1038/nature07441. The authors use live imaging of NCC behavior to show that cell-cell contact inhibition of cell protrusions directs NCC migration, and that this process is mediated by Wnt PCP signaling and RhoGTPase.

- 41.Kasemeier-Kulesa JC, Kulesa PM, Lefcort F. Imaging neural crest cell dynamics during formation of dorsal root ganglia and sympathetic ganglia. Development. 2005;132:235–245. doi: 10.1242/dev.01553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jesuthasan S. Contact inhibition/collapse and pathfinding of neural crest cells in the zebrafish trunk. Development. 1996;122:381–389. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.1.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shnitsar I, Borchers A. PTK7 recruits dsh to regulate neural crest migration. Development. 2008;135:4015–4024. doi: 10.1242/dev.023556. The authors show that PTK7 is required for NCC migration and that it cooperates with Fz to recruit Dsh to the plasma membrane.