Abstract

While the neuropsychological effects of high manganese (Mn) exposure in occupational settings are well known, the effects of lower levels of exposure are less understood. In this study, we investigated the neuropsychological effects of lower level occupational Mn exposure in 46 male welders (mean age = 37.4, sd = 11.7 years). Each welders’ cumulative Mn exposure indices (Mn-CEI) for the past 12 months and total work history Mn exposure were constructed based on air Mn measurements and work histories. The association between these exposure indices and performance on cognitive, motor control, and psychological tests was examined. In addition, among a subset of welders (n=24) who completed the tests both before and after a work shift, we examined the association between cross-shift Mn exposure assessed from personal monitoring and acute changes in test scores.

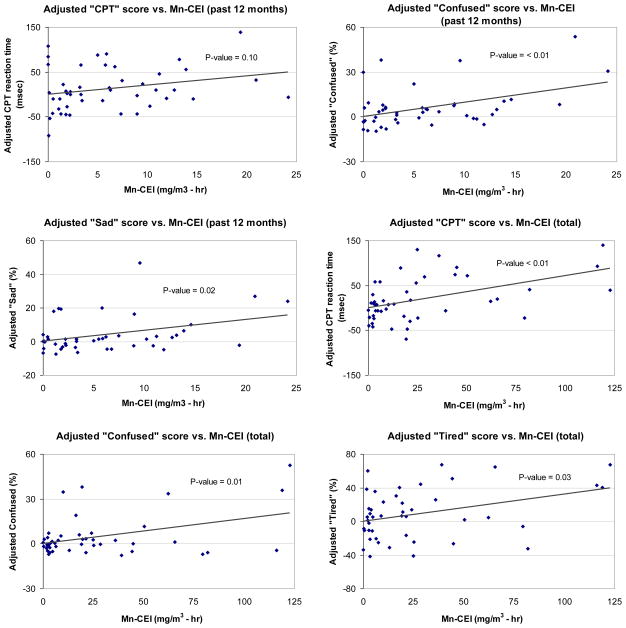

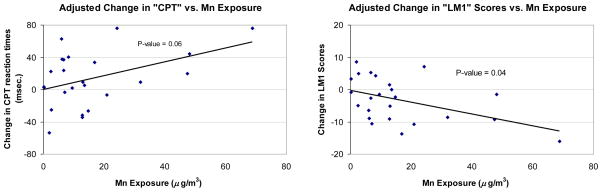

Mn exposures in this study (median = 12.9 μg/m3) were much lower, as compared to those observed in other similar studies. Increasing total Mn-CEI was significantly associated with slower reaction time on the continuous performance test (CPT; p<0.01), as well as worse mood for several scales on the Profile of Mood States (POMS; confused, tired, and a composite of tired and energetic, all p≤0.03). Increasing Mn-CEI over the previous 12 months was significantly associated with worse mood on the sad, tense, and confused POMS scales (all p≤0.03) and the association with worse CPT performance approached significance (p=0.10). Higher Mn exposure over the course of a workday was associated with worse performance on the CPT test across the day (p=0.06) as well as declines in fine motor control over the work-shift (p=0.04), adjusting for age and time between the 2 tests. Our study suggests that even at relatively low Mn exposure levels neuropsychological effects may manifest particularly with respect to attention, mood, and fine motor control.

Keywords: Manganese, low-level manganese exposure, welding fumes, welders, neuropsychological effects, neurotoxic effects

1. Introduction

Manganese (Mn) is a ubiquitous constituent of the environment, and can be found in a variety of biological tissues. It is an essential trace element required for many enzymatic reactions. While Mn deficiency rarely occurs in humans, its toxicity is known to occur in certain occupational settings through inhalation of manganese-containing dust or fume. It is recognized that steel workers and welders are large groups of workers at risk of exposure to Mn [1][2]. Mn absorption into the body occurs primarily via inhalation and is distributed to tissues such as brain, kidneys, small intestine, endocrine glands and bones where it preferentially accumulates in mitochondria [3][4].

The brain is particularly susceptible to excess Mn, and high levels of accumulation can cause a neurodegenerative disorder known as “manganism”. Characteristics of this disease are described as Parkinson-like symptoms, including a movement disorder characterized by tremor, rigidity, dystonia and/or ataxia and psychiatric disturbances including irritability, impulsiveness, agitation, obsessive-compulsive behavior, hallucinations and cognitive deficits such as memory impairment, reduced learning capacity, decreased mental flexibility and cognitive slowing [5][6]. Clinical manganism only occurs following high level acute exposures or long-term chronic exposures [1]. Although manganism differs from Parkinson’s disease according to clinical and pathological parameters, total exposure to Mn at very low levels has been considered a possible determinant that increases the risk of Parkinsonism in more sensitive populations [7]. Low-level Mn exposure could also accelerate the development of a neurotoxic condition indistinguishable from Parkinsonism [8].

Welders are large groups of workers at risk of exposure to Mn in the forms of welding fume or dusts [2][3]. It is estimated that 90% of the mass from welding emissions is in the respirable range and over 80% in particles smaller than 1 μm. Analyses using electron microscopy have indicated that primary particles generated during welding are in the nano-size range (0.01–0.10 μm). However, these particles quickly agglomerate together in the air to form larger particles that usually have mean aerodynamic diameters in the range of 0.1–0.6 μm [9]. Particles in these small sizes can reach the gas exchange region in the lung and then be absorbed into the blood. Inhaled particles in nano-size range may also reach the brain via olfactory transport, as suggested by a number of studies in rats. However, the toxicological significance of olfactory transport of Mn for humans remains controversial [9][10].

Actual exposure levels to Mn during welding may vary, with major factors affecting exposure levels being the type of welding, type of base metal being welded and ventilation. According to a review of studies on Mn exposure among welders [9], the measured concentrations range from <0.1 up to 5 mg/m3. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has a permissible exposure limit (PEL) at 5 mg/m3 for Mn fume (as Mn) [11]. However, a number of occupational studies have demonstrated that neurobehavioral impairment could be affected by exposure to Mn below 1 mg/m3 [12]. Later, based on this evidence, the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH) has set a threshold limit value (TLV) of 0.2 mg/m3 (time weighted average; TWA) for Mn. Additionally, in 2009, ACGIH suggested a respirable Mn TLV of 0.02 mg/m3 TWA [13]. Whether neurological effects less severe than clinical manganism occur at lower levels of Mn exposure is of growing concern in light of increasing ambient levels of Mn in the environment and has only been more recently explored [14]. For example, decrements in intellectual function and hyperactive behaviors, have been reported in general population with early-life exposures to excess Mn [15]. With regard to occupational exposure, several studies in welders and other groups of workers suggest an association between Mn exposure and poorer neuropsychological function [16][17][18][19]. Cumulative exposures to Mn from welding fumes were reported to be associated with subclinical effects on the nervous system, e.g. increased emotional irritability, concentration difficulties, and sleepiness. In addition, a recent review of 18 occupational studies [20] suggested that these neuropsychological effects were also dose-dependent in several studies. Although the levels of Mn exposure in most of these studies were below that which produces manganism, the studies were largely of welders with high exposure levels. In order to investigate the chronic and acute neuropsychological effects of Mn at lower levels of exposure, we examined a group of welders with exposures that were expected to be lower than typical of most occupational studies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Study Population

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Harvard School of Public Health. Informed written consent was obtained from each participant prior to participation. We recruited only apprentice welders at a local union welding school and all 46 welders who came in on one of 7 different study days (in June 2008 and January 2009) were recruited into our study. In June 2008, twenty-eight welders completed a questionnaire and completed several neuropsychological tests at the beginning of the day. Twenty-six of these welders were outfitted for personal gravimetric sampling of welding fume exposure during their workday, 3 of these welders did not weld during the day. Twenty-four welders (22 that did weld during the day and 2 that did not) completed the neuropsychological tests again at the end of the day. The other 18 welders participated in January 2009 in only one neuropsychological testing session during the day without welding.

The welding school consists of a large, temperature-controlled room outfitted with ten workstations where the welders receive instruction and perform welding, cutting, and grinding techniques. These welders primarily performed shielded metal arc welding (SMAW, or STICK) and gas metal arc welding (GMAW, or MIG), most commonly using base metals of mild steel and stainless steel (manganese, chromium, and nickel alloys) with electrodes composed mainly of iron with variable amounts of manganese (1–5%). Plasma arc or acetylene torch cutting and grinding also occurred at the work site.

2.2 Data Collection

2.2.1 Questionnaires

All participants completed self-administered questionnaires that included items on work history, medical history, and life style variables (e.g., age, race, education, income, body mass index (BMI), and food frequency questionnaire). The average amount of Mn consumption from foods (mg Mn/month) was calculated for each participant based on nutrient tables for foods [21][22] and the consumption amounts reported on the questionnaire. A detailed work history (dates of specific jobs, welding tasks on that job, type of metal welded, total hours welded, and respirator use) was collected for the preceding 12 months. For times in the more distant past, only total number of hours welded, type of welding most usually performed, type of respirator most usually used, and usual percentage of time using a respirator was collected. On days that participants welded, each also completed a work log and an exposure diary, to track the number of hours welded, type of welding done, and use of protective equipment and ventilation.

2.2.2 Manganese Exposure Assessment

For workday monitoring, personal gravimetric samples were collected over the duration of the work shift. We used KTL cyclones (GK2.05SH, BGI Inc., Waltham, MA) with aerodynamic diameter cut-point of 2.5 μm, in line with personal sampling pumps (APEX/VORTEX, Casella CEL, UK) drawing 3.5 L/min of air. The cyclone was secured to the participant’s shoulder in the breathing zone area, and the pump was placed in a padded pouch that was carried by the participant for the entire workday. Each cyclone was fitted with a cassette holding a 37 mm polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) membrane filter (Gelman Lab., Ann Arbor, MI). After the sampling, filters from the cyclone samples were weighed for PM2.5 using MT5 micro-balance (Mettler-Toledo Inc., Columbus, OH). They were then analyzed for elemental components using a NITON Portable XRF model XL3t series 600 (ThermoFisher, Billerica, MA). We adopted the NIOSH analytical method #7702 procedures [23] for our filter analyses. Our previous study has demonstrated that this portable technique is reliable and applicable for assessment of exposure to Mn and some other metals on air samples [24].

Mn exposure over a work shift for each participant was calculated as the Mn concentration from the XRF measurement of their personal air filter divided by half the assigned protection factor (APF) [25][26] of the respirator he used on that day. The APF values were divided by two to account for reductions in efficacy with even small leaks resulting from imperfect fitting of the respirators [27].

Air samples were collected to represent exposures around major tasks performed at the union school. Repeated measurements were taken for most of these tasks and the average for a particular task (e.g. STICK welding of mild steel using 7018 electrode) used in the construction of a cumulative Mn exposure index (Mn-CEI) for each individual [17][28]. A Mn-CEI for the past 12 months was calculated using each welder’s report of specific welding tasks and total hours of welding for that task during the past year, and the reported use of respiratory protection. Occasionally welders reported a task for which we did not have air measurements from the school itself, in this case we used typical values from the literature [1]. The Mn-CEI for the past 12 months was derived by summing (equation 1) the products of the average Mn exposure intensity (using arithmetic means) for each welding task the participant performed in the past 12 months and the number of hours worked on that particular task adjusted for the effect of respiratory protection used (equation 2).

| (1) |

| (2) |

Where MnAi is the average air Mn concentration for the ith task; Timei is the total hours spent for the ith task performed in the past 12 months; %respiratorij is the estimated percentage of time the participant used the jth respirator in the ith task; and APFij is the assigned protection factor for the jth respirator used in the ith task (divided by 2 to account for reductions in efficacy from imperfect fitting). This yields a measure of cumulative exposure across all exposed jobs, in mg/m3-hr.

A total work history Mn-CEI for each participant was calculated (equation 3) by summing the Mn-CEI for the past 12 months (equation 1) and a CEI based on the estimated total number of hours welded before the last 12 months (equation 4) that accounted for the type of respiratory protection used the most.

| (3) |

| (4) |

Where MnAk is the average Mn concentration for the welding type that the participant usually performed; Timek is the estimated total hours spent in welding before the past 12 months; APFk is the assigned protection factor for the respirator he usually used (divided by 2 to account for reductions in efficacy from imperfect fitting); %usedk is the estimated percentage of time the participant used that respirator.

2.2.3 Neuropsychological Assessment

At the beginning of each testing day each participant was administered tests to assess the general domains of attention, motor performance, and mood. Two tests—the continuous performance test (CPT) and finger tapping—were from the Neurobehavioral Evaluation System 3 (NES3) [29][30]. The CPT assesses sustained attention and requires the participant to press a computer key whenever a cat appears in a series of animal silhouettes. Outcome measures include reaction time and omission errors. Finger tapping requires the participant to press a computer key as many times as possible with each index finger for a 10-sec period. Five trials per hand (dominant and non-dominant) are performed and scores are mean taps per hand. This test measures manual motor speed and dexterity, and potential left-right differences.

A third test was based on a novel biometric device, Neuroskill™ (VeriFax Corporation, Boulder, CO), that assesses the quality of fine motor control through analysis of handwriting dynamics. This Neuroskill device uses a graphic tablet and accompanying pen connected to a laptop via a computer interface electronic module. Each participant was asked to sign his name and to write a series of “lm” in cursive script 5 consecutive times each. The acceleration of the pen during handwriting is measured along the X and Y-axes of the writing surface. Accompanying software samples these analog signals 200 to 400 times per second and converts them into a digital bit stream representing up to 2000 data points.

Neuroskill assesses the quality of the central mechanism of motor control through analysis of complex signals of handwriting dynamics. The Neuroskill technology takes advantage of the fact that handwriting is made up of “quanta” of preprocessed neural information encoding fine motor movements that are about 100ms in duration [31][32]. These quantal segments are stationary giving handwriting a type of granular stationarity to which Neuroskill applies correlation function analysis in order to establish the criterion of “stability” in motor control. The measure of stability characterizes the ability of the participant to reproduce consistently the preprogrammed micro-movements (strokes) from sample to sample. We computed the maximum of the cross correlation function for the dynamic signals that represent sequences of such elementary movements. For two identical signals the value of the criterion of stability would be equal to one (or 100% correlation). The less consistently a participant can repeat the same handwriting the lower the criterion of stability would be. The Neuroskill measure of handwriting stability is an indication of the correlation between all pairs of handwriting samples (either the 5 signature samples, or the 5 cursive “lm” patterns) provided by the participants at each test session and in essence it is the measure of reproducibility across the samples. The stability score can range from 0 to 100 percent.

To assess neuropsychiatric effects, we used a non-verbal profile of mood states (POMS) questionnaire. Illustrations of faces depicting various dimensions of mood (happy, tense, sad, confused, tired, afraid, angry, and energetic) were presented with nonverbal response scale. On each page, there was a vertical 10-cm line between the neutral face at the top and the face at the bottom depicting a mood state. Each participant was asked to draw a single mark across the line connecting the two faces to show how he felt at that time. The score for each mood dimension (%) is the distance from the neutral face (in cm) times 10. Two composite scores were computed for “happy” and “energetic” and then averaged with “sad” and “tired”, respectively. These two additional scores were also used as outcome variables in our data analysis. The POMS has been shown to have high internal consistency and overall good test-retest reliability [33]. This nonverbal POMS has been previously used in several studies to assess mood states [34][35]. This renders it a useful short scale (requiring only a few minutes of time) of affect and mood.

2.3 Data Analysis

Forty six welders with at least one neuropsychological testing score and past exposure history were included in the data analysis for the association between cumulative exposure and test outcomes. Twenty four of these 46 welders completed both pre- and post- work shift neuropsychological testing sessions for at least one test and had Mn exposure data from personal sampling during that day. These 24 welders were included in the analysis for the association between Mn exposure over a work shift and changes in neuropsychological performances. Only their pre-workshift baseline test scores were used in the analysis with cumulative Mn exposures.

We used ordinary least squares regression to assess the association between Mn-CEIs (past 12-months and total work history) and baseline neuropsychological test scores. For testing over a workshift change in neuropsychiatric test score over the day was regressed on Mn exposure, based on personal air-Mn concentration sampled over that day and respiratory protection used. Finger tapping scores of four participants were not included in the analysis because of errors in the performances of the test. A priori covariates considered were age, race (white, black, others), education (high school or less, vocational school, some college or higher), computer skill (none/little, average/proficient), body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) and average Mn consumption from foods (mg/month). P-values were used to determine statistical significance of the effect estimates, at alpha = 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed with Statistical Analysis System (SAS Institute Inc., NC) version 9.1.3.

3. Results

Gravimetric analysis of 26 personal samples collected over the course of a day in June 2008 revealed that airborne PM2.5 concentrations ranged from 0.057 to 3.041 mg/m3 on days the participants welded (n = 23) and 0.033 to 0.047 mg/m3 on days they did not (n = 3). The median exposure on welding days (0.420 mg/m3) was approximately 10 times higher than that on PM2.5 non-welding days (0.041 mg/m3). From the XRF analyses of air samples, the airborne Mn concentrations ranged from 4.02 to 137.41 μg/m3 (median = 12.9 μg/m3) on welding days and from 0.124 to 0.166 μg/m3 (median = 0.145 μg/m3) on non-welding days.

The Mn-CEI for the 46 welders ranged from 0–24.14 mg/m3-hr (median = 4.19 mg/m3-hr) for the past 12 months, and 0.1–122.7 mg/m3-hr (median = 14.73 mg/m3-hr) for the total work history. Table 1 shows Mn-CEI levels by socio-demographic characteristics of the welders. The mean age of the welders was 37.5 (SD = 11.6) and the median number of hours they had been welding was 1,117.5 (25th–75th percentiles = 528–3,737). The average neuropsychological test scores of the 46 welders are shown in table 2.

Table 1.

Mn-CEI levels by demographic characteristics of the participants.

| Characteristics | Participants N (%) | Mn-CEI Median(25th–75th percentiles), mg/m3-hr |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Past 12 months | Total | ||

| Age | |||

| - < 30 years | 14 (30.4%) | 4.54 (1.98–10.61) | 4.76 (2.22–19.21) |

| - 30 to 40 years | 15 (32.6%) | 5.85 (3.35–9.60) | 10.09 (5.55–23.22) |

| - > 40 years | 17 (37.0%) | 1.28 (0.18–7.43) | 24.19 (4.33–62.19) |

| Hours of Welding | |||

| - ≤ 1,000 hours | 22 (47.8%) | 2.23 (1.28–4.98) | 3.23 (2.21–5.52) |

| - 1,001 to 5,000 hours | 15 (32.6%) | 8.95 (5.63–13.51) | 21.32 (18.53–32.19) |

| - > 5,000 hours | 9 (19.6%) | 5.85 (1.28–11.16) | 79.32 (44.13–116.3) |

| Race | |||

| - White | 36 (78.3%) | 5.64 (1.87–9.70) | 17.80 (4.49–30.32) |

| - Black | 7 (15.2%) | 1.19 (0.33–2.74) | 3.28 (1.34–11.13) |

| - Asian & Hispanic | 3 (6.5%) | 5.85 (2.97–8.50) | 44.85 (22.47–63.32) |

| Education | |||

| - High school or less | 27 (58.7%) | 3.29 (1.24–8.19) | 16.44 (3.81–32.19) |

| - Vocational school | 5 (10.8%) | 5.50 (3.28–6.29) | 6.37 (3.28–21.32) |

| - Some college or more | 14 (30.4%) | 6.26 (2.20–10.05) | 13.45 (3.32–39.37) |

| Language | |||

| - English | 40 (87.0%) | 4.19 (1.71–9.70) | 14.73 (3.27–30.32) |

| - Other | 6 (13.0%) | 4.56 (1.72–7.03) | 14.26 (3.55–39.69) |

| Computer Skill | |||

| - None/Little | 27 (58.7%) | 5.85 (1.77–11.0) | 17.92 (5.55–41.62) |

| - Average/Good | 19 (41.3%) | 2.25 (1.41–8.19) | 5.79 (2.45–24.49) |

| Income | |||

| -≤ $50,000 | 21 (45.7%) | 4.97 (1.90–7.32) | 6.37 (2.25–19.44) |

| - > 50,000 | 23 (50.0%) | 3.18 (1.24–9.60) | 21.24 (4.53–37.52) |

| - Unanswered | 2 (4.3%) | 11.02 (9.22–12.81) | 21.06 (19.49–22.62) |

| Marital Status | |||

| - Never married | 21 (45.7%) | 4.97 (1.90–8.97) | 8.97 (2.69–19.44) |

| - Married | 20 (43.5%) | 2.77 (0.83–6.91) | 22.71 (5.86–46.22) |

| - Divorced/separated | 5 (10.8%) | 11.92 (3.41–12.71) | 39.12 (4.73–62.19) |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | |||

| -≤25 | 8 | 5.41 (1.69–7.81) | 31.66 (18.84–62.71) |

| - 25–30 | 36 | 3.29 (1.47–9.70) | 9.53 (3.06–25.95) |

| - >30 | 2 | 10.20 (7.99–12.40) | 11.85 (8.82–14.89) |

| Mn Consumption | |||

| -≤50 mg/month | 20 | 5.38 (1.91–10.46) | 13.27 (2.53–25.95) |

| - 50–100 mg/month | 16 | 3.35 (1.26–8.96) | 11.00 (4.07–40.37) |

| - >100 mg/month | 10 | 5.30 (0.25–9.00) | 5.45 (5.45–33.14) |

Table 2.

Mean scores and standard deviation of neuropsychological test results*.

| Test | n | Mean | S.D. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Performance Test (CPT), msec | |||

| - Mean reaction time | 46 | 517.87 | 59.18 |

| Finger Tapping Test, # of taps | |||

| - Dominant hand (P) | 42 | 156.19 | 12.56 |

| - Non-dominant hand (NP) | 42 | 144.07 | 17.66 |

| Handwriting Stability, % | |||

| - Signature | 46 | 83.81 | 5.97 |

| - “lm” | 46 | 75.98 | 8.48 |

| Profile of Mood States (POMS), % | |||

| - Happy | 45 | 68.55 | 28.48 |

| - Sad | 45 | 10.25 | 10.72 |

| - Tense | 45 | 16.59 | 17.89 |

| - Confused | 45 | 11.94 | 13.44 |

| - Afraid | 45 | 9.74 | 9.40 |

| - Angry | 45 | 10.16 | 10.42 |

| - Tired | 45 | 35.17 | 31.86 |

| - Energetic | 45 | 38.39 | 27.68 |

| - Avg. Sad/Happy | 45 | 20.85 | 15.85 |

| - Avg. Tired/Energetic | 45 | 48.39 | 25.20 |

For welders who completed neuropsychological tests both before and after a workday, only their first testing scores are included. Finger tapping scores of four welders and POMS scores for a welder who did the test incorrectly are excluded.

Total work history Mn-CEI was significantly associated with worse CPT performance (longer mean reaction times) Likewise, 12-month Mn-CEI was associated with worse CPT scores, though not statistically significant (Table 3). In general, both 12-month and total work history Mn-CEI were associated with worse mood states on the POMS scales, reaching significance with both exposure metrics for the confusion scale. The 12-month Mn-CEI was also significantly associated with worse mood on the sad and tense scales, while the total work history Mn-CEI was also significantly associated with worse mood on the tired and averaged tired/energetic scales (Table 3). Results were similar when additionally adjusting for race, education, income, dietary Mn, and BMI. When three participants with total work history Mn-CEI higher than 100 mg/m3-hr were excluded, the association was similar for the CPT scores (β=0.67, p=0.04). However, the associations with POMS confusion and tiredness scales were no longer significant (β=0.02, p=0.77 and β=0.14, p=0.52, respectively). Although the number of hours welded during the past 12 months and over the total work history were reasonably correlated with the past 12-month Mn-CEI (Spearman ρ = 0.70) and the total work history Mn-CEI (Spearman ρ = 0.93), the results of regression models using hours welded as the exposure metric showed reduced effect sizes compared to the Mn-CEI for the neuropsychological outcomes. Age-adjusted plots of the Mn-CEI relationship with neuropsychological test scores for those associations that were significant and marginially signficant are shown in figure 1.

Table 3.

Parameter estimates (β) and standard error (S.E.) for associations between 12-month and total work history Mn-CEI (one mg/m3-hr increase) and neuropsychological test scores.

| Neuropsychological Test* | n | Per mg/m3-hr Mn-CEI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Past 12 months | Total | ||||||

| β | S.E. | P-value | β | S.E. | P-value | ||

| Continuous Performance Test, msec | |||||||

| - Mean reaction time* | 46 | 2.03 | 1.22 | 0.10 | 0.71 | 0.22 | <0.01 |

| Finger Tapping Test, # of taps | |||||||

| - Dominant hand (Pn)** | 42 | −0.09 | 0.33 | 0.79 | −0.04 | 0.07 | 0.51 |

| - Non-dominant hand (NPn)** | 42 | −0.46 | 0.47 | 0.34 | −0.14 | 0.09 | 0.13 |

| Handwriting stability, % | |||||||

| - Signature** | 46 | −0.10 | 0.15 | 0.51 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.38 |

| - “lm”** | 46 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.50 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.76 |

| Profile of Mood States (POMS), % | |||||||

| - Happy** | 45 | −0.60 | 0.73 | 0.42 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.85 |

| - Sad* | 45 | 0.64 | 0.26 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.56 |

| - Tense* | 45 | 1.00 | 0.44 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.58 |

| - Confused* | 45 | 0.96 | 0.32 | <0.01 | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| - Afraid* | 45 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.32 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.07 |

| - Angry* | 45 | 0.10 | 0.27 | 0.72 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.49 |

| - Tired* | 45 | 0.85 | 0.76 | 0.27 | 0.33 | 0.15 | 0.03 |

| - Energetic** | 45 | −0.62 | 0.68 | 0.37 | −0.23 | 0.13 | 0.08 |

| - Avg. Sad/Happy* | 45 | 0.62 | 0.40 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.98 |

| - Avg. Tired/Energetic* | 45 | 0.74 | 0.59 | 0.22 | 0.28 | 0.11 | 0.02 |

Results are adjusted for age.

Positive β values indicate worse performance with higher Mn exposure

Negative β values indicate worse performance with higher Mn exposure

Figure 1.

The age-adjusted relationship between Mn-CEI (12-month or total work history as indicated) exposure (x-axis) and neuropsychological test score (y-axis) for selected neuropsychological tests. Each point represents an individual welder. The solid line indicates the linear trend, the p-value for which is indicated.

Twenty-four unique welders completed the neuropsychological tests both before and after a work shift. In contrast to the CEIs, Mn during the day was significantly associated with worse handwriting stability for cursive “lm” script, adjusting for age and time between the 2 tests. Mn exposure during the day also appeared to be associated with worse performance on the CPT test although this did not reach statistical significance (P-value = 0.06). Associations with other test scores were not observed (Table 4). Results were generally similar when additionally adjusting for the average tired/energetic POMS score. Adjusted plots of the work shift Mn exposure relation with selected neurological test scores are shown in figure 2. As can be seen, the significant associations were largely dependent on one welder with the highest exposure over the day. Adjusted plots of these associations are shown in figure 2.

Table 4.

Parameter estimates (β) and standard error (S.E.) for associations between workday Mn exposure (1 μg/m3 increase) and change in neuropsychological test scores over the workday.

| Neuropsychological Test | n | Per μg/m3 Mn Exposure |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | S.E. | P-value | ||

| Continuous Performance Test, msec | ||||

| - Mean reaction time* | 24 | 0.86 | 0.44 | 0.06 |

| Finger Tapping Test, # of taps | ||||

| - Dominant hand (Pn)** | 21 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.36 |

| -, Non-dominant hand (NPn)** | 21 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.63 |

| Handwriting stability, % | ||||

| - Signature** | 24 | −0.00 | 0.10 | 0.98 |

| - “lm”** | 24 | −0.18 | 0.08 | 0.04 |

| Profile of Mood States (POMS), % | ||||

| - Happy** | 22 | −0.28 | 0.46 | 0.55 |

| - Sad* | 22 | −0.06 | 0.22 | 0.77 |

| - Tense* | 22 | 0.02 | 0.31 | 0.94 |

| - Confused* | 22 | −0.19 | 0.23 | 0.41 |

| - Afraid* | 22 | −0.04 | 0.17 | 0.82 |

| - Angry* | 22 | 0.08 | 0.21 | 0.73 |

| - Tired* | 22 | 0.65 | 0.53 | 0.24 |

| - Energetic** | 22 | 0.48 | 0.25 | 0.07 |

| - Avg. Sad/Happy* | 22 | 0.11 | 0.25 | 0.68 |

| - Avg. Tired/Energetic* | 22 | 0.08 | 0.34 | 0.81 |

Results are adjusted for age and time between the 2 tests. For a single test, participants who did not complete both pre- and post- tests, did the test incorrectly, or had incomplete exposure information were not included in the analysis.

Positive β values indicate worse performance

Negative β values indicate worse performance

Figure 2.

The age- and time between tests-adjusted relationship between Mn exposure (x-axis) and relative change in test score over the workshft (postshift – preshift) (y-axis) for selected neuropsychological tests. Each point represents an individual welder. The solid line indicates the linear trend, the p-value for which is indicated (positive trend means a worse performance for CPT, negative trend mean a worse performance at the end of the day for LM1).

4. Discussion

Among welders with Mn exposures that these low levels, we found higher cumulative exposure to manganese to be associated with worse performance on several neuropsychological tests. As has been noted before [16][36], the assessment of mood appeared particularly sensitive in that significant associations with mood were seen related to the 12-month Mn-CEI and total work history Mn-CEI. The CPT, a test of sustained attention, also appeared sensitive to Mn as worse performance on this test was significantly associated with increasing total work history Mn-CEI, and approached statistically significant associations with 12-month Mn-CEI and Mn exposure over a work shift. When three participants with particularly high total work history Mn-CEI (higher than 100 mg/m3-hr) were excluded, the association with the CPT scores was similar and still statistically significant. In contrast, the associations with mood on the confusion and tiredness scales were no longer statistically significant. This may suggest that effects of Mn exposure on mood are only seen at slightly higher Mn exposure levels than for the CPT, but since there were only a few participants with total work history Mn-CEI in this higher range in our study, we cannot rule out chance as an explanation. Further investigation in welders with total work history Mn-CEI in this high range is needed. Intriguingly, Mn exposure over a work shift was associated with worse stability of handwriting for the production of cursive script (could be due to tiredness of welding). We did not find associations between Mn and other tests, including finger tapping, adjusting for age and time between the 2 tests, which may be the result of the generally low exposure levels of our study participants and sensitivity of the tools. Overall, however, these results suggest that Mn can have adverse neuropsychological effects at very low levels and on a very acute time scale—over the course of a work shift.

Earlier studies of neurological effects of occupational exposure to Mn focused on occupational settings such as ferroalloy plants, smelters, and battery manufacturing facilities, in which exposures to Mn are generally higher than in welding, with studies of welders being more recent [37]. Overall, the evidence is generally relatively consistent for an association with measures of mood and motor function including reaction times. Among welders, although neuropsychological effects have been described, clear evidence for a dose-response relation with Mn exposure is less clear. Several early studies are limited by self-reported symptoms or only having compared welders to a control group often with questionable adequacy [37]. Nonetheless, some evidence does exist. One of the earlier welder studies examined welders exposed to 1–4 mg Mn/m3 for a mean period of 16 years and found a significant association between duration of exposure and reaction time [38]. A study in Japan examined welders and non-welders in several industries with current Mn exposures ranging from 0.005–9.27 mg Mn/m3 [39]. This study found associations between years of welding and tests of motor function and reaction time in tests of attention. Several reports have come from studies of welders on the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, which have reported significant associations between Mn exposure measures and worse neuropsychological function in several cognitive domains including motor tasks, mood, executive function, sustaining concentration and sequencing, verbal learning, working and immediate memory [16][17][40][41][42]. These welders had had many years of welding experience including many months of confined space welding on the Bay Bridge and so were overall much more highly exposed than the apprentice welders we studied here. The Bay Bridge welder studies also involved workers that were plaintiffs in litigation, including some referred for assessment because of symptoms.

Our study setting is unique in that we targeted apprentice welders and thus covered a range of Mn exposure lower than those found in prior studies among welders who had on average worked for many fewer years than in other studies. Although we measured Mn in PM2.5, which would miss larger particles captured in total dust or inhaled fraction samples, larger particles are expected to make up a small portion of welding fumes. It has been reported that 80–90% of particles produced in most welding fumes are in the respirable range or smaller [8][9]. We also included consideration of typical respirator use in calculating our CEI, which, from our review of similar studies on welding fumes exposure, has never been done despite the known exposure-reducing effects of such use. In addition, we explored possible effects across a work shift. Thus, we were in a position to identify very early effects of Mn exposure. Our results for total work history Mn exposures are in line with what has been seen in some other studies in that we found significant associations with mood and reaction times. We did not see any association with finger tapping, although it may be that our levels of exposure were too low to observe such associations. Our results with cumulative Mn exposure over the last 12 months suggest that even at the much lower levels seen over a 12 month span in our study population, associations between Mn and some neuropsychological outcomes can be seen. In particular, mood and reaction time, although the association with reaction was only significant at p=0.10.

Mn exposure over the course of a work shift appeared to be related to handwriting stability. The neuroskill device has been previously reported to be sensitive to dopaminergic medications among Parkinson’s disease patients [43], but it has not been explored in relation to environmental toxicant exposures. The production of free handwriting, for example signatures, is considered to be accomplished by the sequential activation of elemental open-loop (not under feedback control) motor commands, or strokes [31][44]. The production of sequential cursive “lm”s is a less familiar task than one’s signature and thus likely has more of a closed-loop component (involving visuo-motor feedback control) than production of a signature. The fact that we found an association with production of cursive “lm”s, but not signatures may suggest that the Mn exposure affected feedback control abilities more than open-loop handwriting production. It is unclear, however, why the handwriting stability assessment seemed related to Mn exposure over a work shift, but not cumulative exposure over the last 12 months or the total work history. It seems unlikely that handwriting stability is influenced by hand fatigue due to force exertion while welding, because it is unclear why then hand fatigue would affect closed loop, but not open loop, handwriting production, and that fatigue would have to correlate with actual Mn exposure to explain our findings. Furthermore, we adjusted for time between the two tests. It is possible, particularly given our findings with respect to reaction times on the attention task, that at these levels Mn causes impairment of cognitive control responsible for the feedback aspect of closed-loop motor production rather than pure motor functions involved in generation of ballistic automatically produced movements. We also found that Mn exposure over the course of a work shift was marginally associated with reaction time scores. While we controlled for the time between the tests as a surrogate for fatigue over the work shift, we cannot rule out confounding by fatigue. However we saw similar results when we controlled for the workers self-report of fatigue (the change in average tired/energetic scores on the POMS scales), suggesting that some of the effects were likely due to exposure.

One limitation of the present study is our small sample size. There were only 46 participants in our study so that our statistical power to detect the signification associations was not very high. Also, all the participants were recruited from the same workplace. Our estimation of total work history Mn-CEI could be less accurate than the past 12 months Mn-CEI because of less accurate recall and since a complete detailed work history was only captured for the previous 12 months. For both the 12-month and total work history Mn-CEI, however, although the correlations with hours welded were high (Spearman ρ = 0.93 for the total work history, ρ = 0.70 for 12-month), the associations with neuropsychological outcomes were stronger for the Mn-CEI exposure estimate than hours welded. This can be considered as indirect validation of our Mn-CEI estimation.

5. Conclusions

Our results suggest that an exposure-response relation can be seen between Mn exposure and several neuropsychological tests even at lower levels of Mn exposure than typically seen in other occupational Mn exposure studies. In addition, the novel fine motor control testing device, Neuroskill, that we explored may be a useful tool to pick up subtle effects of Mn exposure, although further exploration of this tool is needed. Although our study was limited by a small number of participants, our data suggest that occupational Mn may have neuropsychological effects at exposure levels lower than those previously examined. Longitudinally following welders from the beginning of their welding careers could provide important information on critical exposure levels in the development of neuropsychological effects.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Kimberly Newton, Melinda Power, Michael Sirois, and Rebecca Francis for their administrations of neuropsychological tests. Special thanks to the staff and members of the International Brotherhood of Boilermakers, Local No. 29, Quincy, MA. This research was supported by CDC/NIOSH training grant # T42 OH 008416-02, NIEHS grant # ES009860 and CPWR through NIOSH cooperative agreement OH009762. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of CPWR or NIOSH.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions

WL contributed to study design, samples collection and analysis, data analysis and interpretation of the results, and manuscript preparation. XL contributed to study design, statistical analyses and critical review of the manuscript. DCC, SCF and JMC contributed to data collection and review of the manuscript. RS and AL contributed to the review and interpretation of findings from Neuroskill handwriting device. RFH and MW contributed to study design, data analysis, interpretation of the results, and critical review of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Antonini JM. Health Effects of Welding. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2003;33(1):61–103. doi: 10.1080/713611032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stellman JM, editor. ILO Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety. 4. International Labour Organization; Geneva: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Agency (ATSDR) Toxicological Profile for Manganese. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feldman RG. Occupational and Environmental Neurotoxicology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Josephs KA, Ahlskog JE, Klos KJ, Kumar N, Fealey RD, Trenerry MR, Cowl CT. Neurologic Manifestations in Welders with Pallidal MRI T1 Hyperintensity. Neurology. 2005;64:2033–2039. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000167411.93483.A1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levy BS, Nassetta WJ. Neurologic Effects of Manganese: A Review. Int J Occup Environ Heal. 2003;9:153–163. doi: 10.1179/oeh.2003.9.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lucchini R, Martin CJ, Doney BC. From Manganism to Manganese-Induced Parkinsonism: A Conceptual Model Based on the Evolution of Exposure. Neuromol Med. 2009;11:311–321. doi: 10.1007/s12017-009-8108-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin CJ. Manganese neurotoxicity: Connecting the dots along the continuum of dysfunction. Neurotoxicology. 2006;27:347–349. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antonini JM, et al. Fate of Manganese associated with the Inhalation of Welding Fumes: Potential Neurological Effects. Neurotoxicology. 2006;27:304–310. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorman DC, et al. Application of Pharmacokinetic Data to the Risk Assessment of Inhaled Manganese. Neurotoxicology. 2006;27:752–764. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) [Accessed July 28, 2010];Occupational Safety and Health Guideline for Welding Fumes. [Online] Available at http://www.osha.gov/SLTC/healthguidelines/weldingfumes.

- 12.Lucchini R, Apostoli P, Perrone C, et al. Long Term Exposure to “Low Levels” of Manganese Oxides and Neurofunctional Changes in Ferroalloy Workers. Neurotoxicology. 1999;20(2–3):287–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH®): 2009 TLV®s and BEI®s, Threshold Limit Values and Biological Exposure Indices for Chemical Substances and Physical Agents. Cincinnati, Ohio: ACGIH; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aschner ME, Erikson KE, Dorman DC. Manganese Dosimetry: Species Differences and Implications for Neurotoxicity. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2005;35:1–32. doi: 10.1080/10408440590905920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winder BS, Salmon AG, Marty MA. Inhalation of an Essential Metal: Development of Reference Exposure Levels for Manganese. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2010.02.007. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bowler RM, Nakagawa S, Drezgic M, et al. Manganese Exposure: Neuropsychological and Neurological Symptoms and Effects in Welders. Neurotoxicology. 2006;27:315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bowler RM, Roels HA, Nakagawa S, et al. Dose-effect Relationships between Manganese Exposure and Neurological, Neuropsychological and Pulmonary Function in Confined Space Bridge Welders. Occup Environ Med. 2007;64:167–177. doi: 10.1136/oem.2006.028761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finley BL, Santamaria AB. Current Evidence and Research Needs Regarding the Risk of Manganese-Induced Neurological Effects in Welders. Neurotoxicology. 2005;26:285–289. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mergler D. Neurotoxic Effects of Low Level Exposure to Manganese in Human Populations. Environ Res Section A. 1999;80:99–102. doi: 10.1006/enrs.1998.3902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zoni S, Albini E, Lucchini R. Neuropsychological Testing for the Assessment of Manganese Neurotoxicity: A Review and a Proposal. Am J Ind Med. 2007;50:812–830. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Department of Preventive Medicine. Nutritional Fact Sheet: Manganese. Northwestern University; [Accessed: Nov. 19, 2009]. http://www.feinberg.northwestern.edu/nutrition/factsheets/manganese.html. [Google Scholar]

- 22.International Programme on Chemical Safety. Environmental Health Criteria for Manganese. World Health Organization (WHO) Publication; Geneva: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) Method #7702 Lead by Field Portable XRF, DHHS – NIOSH Publication No. 98–119. 4. Cincinnati, Ohio: 1998. NIOSH Manual of Analytical Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laohaudomchok W, Cavallari JM, Fang SC, Lin X, Herrick RF, Christiani DC, Weisskopf MG. Assessment of Occupational Exposure to Manganese and Other Metals in Welding Fumes by Portable X-ray Fluorescence Spectrometer. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2010;7(8):456–465. doi: 10.1080/15459624.2010.485262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) DHHS – NIOSH Publication No. 2005–100. Cincinnati, Ohio: 2004. NIOSH Respirator Selection Logic. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Assigned Protection Factors for the Revised Respiratory Protection Standard, U.S. Department of Labor – OSHA Publication No. 3352–02. Salt Lake City, Utah: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heirbaum J. OSHA’s Assigned Protection Factors for Respiratory Protection. [Accessed: Dec. 18, 2009];Workplace Magazine. http://www.workplacemagazine.com/contedchooseest.asp.

- 28.Nieuwenhuijsen MJ. Exposure Assessment in Occupational and Environmental Epidemiology. Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Letz R. NES3 User’s Manual. Neurobehavioral Systems; Atlanta, GA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Letz R, DiIorio CK, Shafer PO, Yeager KA, Schomer DL, Henry TR. Further Standardization of Some NES3 Tests. Neurotoxicology. 2003;24:491–501. doi: 10.1016/S0161-813X(03)00044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morasso P, Mussa Ivaldi FA. Trajectory Formation and Handwriting: A Computational Model. Biol Cybern. 1982;45:131–142. doi: 10.1007/BF00335240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schomaker L, Nijtmans J, Camurri A, et al. Drawing, and Pen Gestures, Report No.: ESPRIT BRA No. 8579. Miami: 1995. A Taxonomy of Multimodal Interaction in the Human Information Processing System: Two-dimensional Movement in Time: Handwriting. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Curran SL, Andrykowski MA, Studts JL. Short Form of the Profile of Mood States (POMS-SF): Psychometric Information. Psychol Assessment. 1995;7(1):80–83. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grandjean P, Weihe P, White RF, et al. Cognitive Deficit in 7-Year-Old Children with Prenatal Exposure to Methylmercury. Neurotoxicology. 1997;19(6):417–428. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(97)00097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saddik B, Williamson A, Nuwayhid I, Black D. The Effects of Solvent Exposure on Memory and Motor Dexterity in Working Children. Public Health Rep. 2005;120:657–663. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anger WK, Liang YX, Nell V, et al. Lessons Learned—15 Years of the WHO-NCTB: A Review. Neurotoxicology. 2000;21(5):837–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Santamaria AB, Cushing CA, Antonini JM, Finley BL, Mowat FS. State-of-the-Science Review: Does Manganese Exposure during Welding Pose a Neurological Risk? J Toxicol Env Heal B. 2007;10:417–465. doi: 10.1080/15287390600975004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siegl P, Bergert KD. A Method of Early Diagnostic Monitoring in Manganese Exposure. Z Gesamte Hyg. 1982;28(8):524–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jin Y, Kim Y, Kim KS, et al. Performance of Neurobehavioral Tests Among Welders Exposed to Manganese. Korean J Occup Environ Med. 1999;11(1):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bowler RM, Mergler D, Sassine MP, Larribe F, Hudnell K. Neuropsychiatric Effects of Manganese on Mood. Neurotoxicology. 1999;20(2–3):367–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bowler RM, Gysens S, Diamond E, Booty A, Hartney C, Roels HA. Neuropsychological Sequelae of Exposure to Welding Fumes in a Group of Occupationally Exposed Men. Int J Hyg Envir Heal. 2003;206:517–529. doi: 10.1078/1438-4639-00249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park RM, Bowler RM, Eggerth DE, Diamond E, Spencer KJ, Smith D, Gwiazda R. Issues in Neurological Risk Assessment for Occupational Exposures: The Bay Bridge Welders. Neurotoxicology. 2006;27(3):373–384. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Contin M, Martinelli P, Shrairman R, et al. Handwriting in Parkinson’s Disease: the Effect of Disease Severity and Acute Levodopa Dosing. Mov Disord. 2007;22(suppl 16):194. [Google Scholar]

- 44.AJWM. Thomassen and HL Teulings, Time, size and shape in handwriting, exploring spatiotemporal relationships at different levels. In: Michon JA, Jackson JB, editors. Time, mind and behavior. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 1985. pp. 253–263. [Google Scholar]