Introduction

The ocular surface is constantly exposed to a myriad of pathogens yet despite this unrelenting challenge, the cornea and conjunctiva rarely succumb to infection. This is due to that fact that the ocular surface is well equipped with multiple defense mechanisms to ward off potential pathogens, including an intact ocular surface epithelium that forms a physical barrier from the external environment and enzymes and other proteins in the tear film that have potent antimicrobial activity (Sack et al., 2001). A number of cationic antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) have also been identified in human corneal and conjunctival epithelial cells such as human β-defensin (hBD) -1-3 and cathelicidin (LL-37). hBD-1, hBD-3 and LL-37 are constitutively expressed by both corneal and conjunctival epithelia whereas hBD-2 expression is inducible by conditions mimicking injury, inflammation and in response to bacterial products (Gordon et al.,2005; McDermott et al., 2001, 2003; McNamara et al.,1999; Narayanan, et al.,2003).

Cationic antimicrobial peptides exert their antimicrobial activity through electrostatic interactions with negatively charged microbial membranes and this interaction is salt sensitive for some AMPs (Zasloff, 2002). Recent in vivo studies in animal models have shown that cathelicidin and defensins play an important role in protecting the ocular surface from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) infection. Mice deficient in cathelicidin-related antimicrobial peptide (CRAMP), the murine homologue of LL-37, were more susceptible to PA keratitis, had significantly delayed bacterial clearance and an increased number of infiltrating neutrophils in the cornea (Huang et al., 2007a). Similar findings were observed for BALB/c mice when expression of either mBD-2 or mBD-3, but not mBD-1 or mBD-4, was knocked down by siRNA (Wu et. al., 2009a, 2009b). Also Kumar et al. (2008) noted that pre-treatment with flagellin markedly reduced the severity of subsequent PA infection in C57BL/6 mice. This was in part due to induction of corneal expression of the antimicrobial molecules, nitric oxide and CRAMP. They also observed similar results in vitro, as flagellin pre-treatment enhanced PA induced expression of hBD-2 and LL-37 in human corneal-limbal epithelial cells (Kumar et al., 2007).

In addition to their antimicrobial effects, defensins have been shown to modulate a variety of cellular activities including chemotaxis of T cells, dendritic cells (Chertov et al.,1996; Yang et al.,1999), and monocytes (Territo et al.,1989), stimulation of epithelial cell and fibroblast proliferation (Murphy et al.,1993; Aarbiou et al.,2002; Li et al. 2006), stimulation of cytokine production (Chaly et al., 2000; Van Wetering et al.,1997), and stimulation of histamine release from mast cells (Scott et al., 2002; Niyonsaba et al., 2001). LL-37 is derived from the cleavage of human cationic antimicrobial protein (hCAP)-18, and has been shown to be chemotactic for neutrophils, mast cells, monocytes, T lymphocytes and is thought to stimulate inflammation through modulating chemokine and cytokine production by macrophages and histamine release from mast cells (Befus et al., 1999; Niyonsaba et al., 2001). Huang et al. (2006) reported that LL-37 can induce human corneal epithelial cell (HCEC) migration and secretion of IL-8, IL-6, and IL-1β and TNF-α. Similarly, Li et al. (2008) found that α-defensin human neutrophil peptide-1 (HNP-1), hBD-2 and hBD-3 stimulated the production of cytokines and chemokines such as IL-6, IL-8 and RANTES in a normal human conjunctival epithelial cell line (IOBA-NHC) which in turn are likely involved in the recruitment of inflammatory cells following injury or insult to the ocular surface.

The ability of the ocular surface to respond to pathogens is in part attributed to a family of receptors called toll-like receptors (TLRs) which recognize conserved motifs on pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) on microbes leading to the production of inflammatory cytokines and co-stimulatory molecules, thus initiating innate and adaptive immunity (Janeway and Medzhitov, 2002). Toll-like receptors are expressed on a wide variety of cell types and in humans there are 10 functional TLRs, each having distinct ligands. TLR2, which forms heterodimers with TLR1 and 6, recognizes bacterial and mycoplasma lipoproteins, yeast carbohydrates and also host heat shock protein (HSP)70 (Takeuchi et al., 2002; Yang et al., 2006). TLR3 responds to double-stranded RNA (Alexopoulou et al.,2001) while TLR4 interacts with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and various host molecules such as HSP60 (Beutler, 2002; Tsan and Gao, 2004). TLR5 recognizes bacterial flagellin (Hayashi et al., 2001). TLR7 and 8 recognize single stranded RNA, (Heil et al., 2004 and Diebold et al., 2004) and TLR9 responds to bacterial and viral unmethylated DNA CpG motifs (Hemmi et al., 2000; Tabeta et al., 2004). TLR10 is able to homodimerize and form heterodimers with TLRs 1 and 2 (Hasan et al., 2005) suggesting that it may be sensitive to similar PAMPs as TLR2 and 1. For more details on TLRs and their roles in ocular surface disease, the reader is referred to a recent review article by Redfern and McDermott (2010).

A link between TLR activation and upregulation of AMP expression has been established in a number of tissues. For example, in respiratory epithelial cells, stimulation of TLR2 with peptidoglycan (PGN) or lipopeptide upregulated hBD-2 expression (Hertz et al., 2003; Homma et al., 2004). Peptidoglycan also induced hBD-2 expression in intestinal epithelial cells (Vora et al., 2004) and PGN and yeast wall particles induced hBD-2 expression in human keratinocytes (Kawai et al., 2002). Also LL-37 expression can be induced by stimulation through TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9 in monocyte-derived macrophages (Rivas-Santiago et al., 2008)

Upregulation of β-defensins and LL-37 through the activation of TLRs may play a role in the innate and adaptive immune system by providing the ocular surface with direct defense against various pathogens and stimulating the recruitment and activation of immune and inflammatory cells. To further investigate the link between TLR activation and AMPs, we determined TLR expression in various ocular surface epithelial cells, in the process confirming some previous observations by others, and extended this to stromal cells. As they are a first-line of defence against pathogens invading the ocular surface we studied both corneal and conjunctival epithelial cells. Three sources of corneal epithelial cell were investigated: a cell line, primary cultured cells and cells from cadaver corneas. Comparisons among these are helpful to elucidate effects due to culture conditions/cell transformation and hence identify the actual TLR profile that most likely is present in vivo. Similarly, a cell line and cells isolated by impression cytology from human subjects were used to study conjunctival epithelial TLR expression. Further, as penetrating corneal injury will also allow pathogens direct access to the corneal stroma we also investigated TLR expression by keratocytes in cadaver corneas and by their repair phenotype, the corneal fibroblast, in cell culture. Using a panel of agonists, we determined if TLR activation stimulates the expression of AMP (defensins and LL-37) mRNA and the production of functionally active AMPs that are effective in killing PA. Furthermore, we also determined if AMPs and TLR agonists can in turn modulate TLR expression in ocular surface cells.

Methods

Corneal and conjunctival cells

Human corneas unsuitable for transplantation were obtained from eye banks within 2–7 days of death. The tissue was obtained in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki regarding research involving human tissue. The average donor age was 67 ± 11 years. Human corneal epithelial cells and stromal keratocytes were isolated as previously described by McDermott et al., (2003) and Pei et al., (2006) respectively. The epithelial cells were maintained in EpiLife medium (Invitrogen; Portland, OR). For some experiments, the isolated stromal cells were cultured in the presence of 10% FBS to induce transformation into the corneal fibroblast phenotype (Fini, 1999). Scraped epithelium, freshly isolated stromal cells and primary cultured cells (passage 1 for epithelial cells, passage 1–2 for fibroblasts) were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until RNA extraction and analysis of TLR1-10, defensin and LL-37 mRNA expression by RT-PCR. Normal human conjunctival (IOBA-NHC) epithelial cells (Diebold et al., 2004) were cultured in DMEM-F12 (1:1 vol/vol), containing 10% FBS, 2 ng/mL mouse epidermal growth factor (EGF), 1 µg/mL bovine insulin, 0.1 µg/mL cholera toxin, 5 µg/mL hydrocortisone, 2.5 µg/mL amphotericin B, and a penicillin streptomycin mixture (5000 U/mL and 5000 µg/mL, respectively). SV40 HCEC were maintained in SHEM (DMEM-Ham’s F12, 1:1 by volume) supplemented with 10% FBS, mouse EGF (0.01 µg/mL), bovine insulin (5ng/mL), cholera toxin (0.1 µg/mL and a penicillin and streptomycin mixture (5000 U/mL and 5000 µg/mL, respectively). Cultured cells were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2. IOBA-NHC (passages ranged between 72–89) and SV40 HCEC (passages ranged from 17–38) were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until RNA extraction and analysis of TLR1-10, hBD-1-3 and LL-37 mRNA expression by RT-PCR.

Conjunctival impression cytology

All procedures involving human subjects were in accordance with the Tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the University of Houston Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and none had a history of ocular surface disease. The average donor age was 32 ± 5 years of age. A drop of 0.5% proparacaine (Bausch and Lomb; Rochester, NY) was instilled on the eye. A 13 × 6.5mm sterilized polyether sulfone membrane (Pall Gelman; East Hills, NY) was placed on the bulbar conjunctiva for 2–5 seconds, removed, and placed in 350µls of RNeasy RLT lysis buffer (Qiagen; Valencia, CA) and vortexed for 60 seconds. The membrane was removed and the samples stored at −80°C until RNA extraction and analysis of TLR1-10 mRNA expression by RT-PCR.

Exposure to TLR agonists and antimicrobial peptides

To determine if TLR activation upregulates AMP or TLR expression, SV40 HCEC, IOBA-NHC or primary HCEC were grown to subconfluency in a 12 well plate. The media was then replaced with antibiotic-free and serum-free (SV40 and IOBA-NHC) or supplement-free (primary HCEC) media and the cells were incubated overnight at 37°C. The cells were then treated with various TLR agonists using the concentrations recommended by the manufacturer (Invivogen, San Diego, CA), TLR1/2 Agonist: Pam3CSK4 (1 µg/ml), TLR2 Agonist: HKLM (108 cells/ml), TLR3 Agonist: Poly(I:C) (1 µg/ml), TLR4 Agonist: LPS E. coli K12 (1 µg/ml), TLR5 Agonist: Flagellin S. typhimurium (1 µg/ml), TLR6/2 Agonist: FSL1 (1 µg/ml), TLR7 Agonist: Imiquimod (1 µg/ml), TLR9 Agonist: ODN2006 (5µM), 10ng/ml of IL-1β (positive control for hBD-2) or serum and antibiotic-free media alone for 24hrs at 37°C. Following TLR agonist treatment, the media was collected and centrifuged (1400g for 2 min) to remove cell debris, snap frozen and stored at −80°C until further analysis by antimicrobial assay or immunoblotting. The cells were harvested in RNeasy RLT lysis buffer, snap frozen and stored at −80°C until RNA extraction for analysis o f hBD1,2,3 or LL-37 mRNA expression. To determine if AMPs modulate TLR mRNA expression, SV40 HCEC, IOBA-NHC or primary HCEC were treated with either 3µg/ml of hBD-2 (Peprotech; Rocky Hill, NJ), 5µg/ml of LL-37 (American Peptide Company; Sunnyvale, CA) or serum-free (SV40 and IOBA-NHC) or supplement-free (primary HCEC) media and incubated for 24 hours at 37°C. The cells were har vested in RNeasy RLT lysis buffer, snap frozen and stored at −80°C until RNA extraction and RT-PCR for TLR1-10 mRNA expression.

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction for detection of TLR1-10, hBD1-3 and LL-37

Total RNA from HCEC (scraped, cultured and SV40 cell line), keratocytes, stromal fibroblasts, and IOBA-NHC cells was extracted using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). For conjunctival impression cytology (CIC) samples, RNA was extracted using an RNeasy Micro Kit. RNA elution columns were DNase treated prior to RNA elution to avoid genomic DNA contamination. To detect TLR (1-10), hBD-1-3 and LL-37 expression one step RT-PCR was carried out with a Superscript I kit using 0.25 µg of RNA and 25pmol of primers per reaction. Amplification of the cDNA was performed for 40 cycles of: denaturation at 94°C for 50 s; annealing at 58°C for 30 s; extension at 72°C for 1 min. TLR1-10 (Ueta et al., 2004), glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), hBD1-3 (Narayanan et al., 2003) and LL-37 (Huang et al., 2006) primers were used as previously described. PCR products were analyzed by agarose (1.3%) gel electrophoresis with ethidium bromide staining. A digital image was captured using an Alpha Imager gel documentation system (Alpha Innotec; San Leandro, CA). For samples exposed to AMPs, the pixel intensity of TLR PCR products was determined and normalized to GAPDH, the internal control, and calibrated to non-treated samples. TLR PCR products that demonstrated a change in expression following antimicrobial peptide treatment were analyzed on an agarose gel after 30, 35, 40 and 45 cycles to confirm linear amplification. The data were analyzed by Student's t-test with values of P ≤ 0.05 being considered significant. The RT-PCR products were sequenced (Seqwright; Houston, TX) to confirm their identities. Human spleen and U937 cell RNA were used as positive controls for TLR mRNA transcript expression. No PCR product was obtained in controls in which either the RNA or reverse transcriptase was omitted.

Real-Time PCR for detection of GAPDH, hBD-2, LL-37, TLR4, 5 and 9

Total RNA from SV40 HCEC and IOBA NHC cells was extracted using a RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) as describe above. cDNA was generated using SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). Samples containing no reverse transcriptase or water in place of RNA (no template control) served as negative controls. Real-time PCR was used to quantitate mRNA expression of GAPDH, hBD-2, LL-37, TLR4, 5 and 9. Primers were as follows: GAPDH Forward: GACCACAGTCCATGCCATCA, GAPDH Reverse: CATCACGCCACAGTTTCC, hBD-2 Forward: GACTCAGCTCCTGGTGAAGC hBD-2 Reverse: TTTTGTTCCAGGGAGACCAC, LL-37 Forward: GGACAGTGACCCTCAACCAG, LL-37 Reverse: AGAAGCCTGAGCCAGGGTAG TLR4 Forward: AATCCCCTGAGGCATTTAGG, TLR4 Reverse: AAACTCTGGATGGGGTTTCC, TLR5 Forward: ACTGACAACGTGGCTTCTCC TLR5 Reverse: GTCAATTGCCAGGAAAGCTG, TLR9 Forward: CCTTCCCTGTAGCTGCTGTC, TLR9 Reverse: GACTTCAGGAACAGCCAGTTGPCR amplification of cDNA was performed with Brilliant SYBR Green QPCR Master Mix (Stratagene; La Jolla, CA) using specific primers at optimized concentrations. Amplified gene products were normalized to GAPDH, the internal control and calibrated to non-treated samples. The relative change of treated versus control samples was then determined with the value of control samples being normalized to one. The data were analyzed by Student's t-test with values of P ≤ 0.05 being considered significant. Disassociation melt curves were analyzed to ensure reaction specificity. For each experiment, the samples were analyzed in triplicate and the mean relative quantity of TLR expression was calculated. Data are representative of a minimum of three experiments and were analyzed using an unpaired Student’s t-test where P ≤ 0.05 was considered a significant difference.

Immunostaining for TLR3, 5 and 9 in human corneas and primary cultured fibroblasts

Human corneas unsuitable for transplantation were obtained from eye banks and embedded in OCT (Optimal Cutting Temperature compound) upon receipt, frozen, and then 10µm cryosections were fixed with acetone. Primary cultured fibroblasts (passage3–6) were cultured into an 8 well chamber slide until subconfluency. Fibroblasts and human cornea cryosections were incubated with blocking solution (10% goat serum, 0.05% gelatin, 5% bovine serum albumin and 0.05% Tween-20 diluted in PBS) for two hours at room temperature. After blocking, the sections were incubated with either 1µg/ml rabbit anti-TLR9 (Abcam; Cambridge, MA), 10µg/ml mouse anti-TLR3 (Imgenex; San Diego, CA) or 10µg/ml mouse anti-TLR5 (Imgenex) antibody at 4°C overnight and then with 5µg/ml Alexa 546 or 6.6µg/ml of 488-conjugated second antibody (Invitrogen) in blocking solution for one hour at room temperature. As a negative control, some sections were incubated with the relevant isotype control instead of the primary TLR antibody. Coverslips were mounted with ProLong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen) and the sections viewed with a DeltaVison imaging system (Applied Precision; Issaquah, WA).

Flow cytometry for TLR3 and 9

Freshly isolated stromal keratocytes were harvested as described above for immunostaining and placed into culture to differentiate into corneal fibroblasts and used at passage 3. Cultured SV40 HCEC and fibroblasts cells were pelleted, resuspended and permeabilized in 3% BSA/0.1% Triton-X to determine TLR intracellular expression. Equal amounts of cells were aliquoted into 15ml conical plastic tubes and blocked with 3% BSA for 30min. The cells were then incubated for an additional 30min with either 1µg/ml rabbit anti-TLR9 (Abcam) or 10µg/ml mouse anti-TLR3 then with Alexa 488-conjugated second antibody in blocking solution. Flow cytometry was performed on a FACS Canto II (BD Biosciences; San Jose, CA) and the data were analyzed using FlowJo flow cytometry analysis software.

Antimicrobial assay

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) strain ATCC19660, a cytotoxic strain which can induce severe ocular infection in experimentally infected mice was tested in this study and prepared as previously described (Huang et al., 2006). The antimicrobial activity of media collected from primary HCEC treated with TLR3, 5 and 6/2 agonists was tested against PA based on a previously described protocol (Kumar et al., 2006). Primary HCEC cells grown in antibiotic-free media were treated for 20hrs with a combination of TLR3 agonist: PolyI:C (1 µg/ml), TLR5 agonist: Flagellin S. typhimurium (1 µg/ml) and TLR6/2 agonist: FSL1 (1 µg/ml) or media alone in a six well plate; the culture media was collected and centrifuged (1400g for 2min) to remove cell debris and used immediately or snap frozen and stored at −80°C until further analysis. One milliliter of this media was inoculated with 200 colony forming units of PA19660 and the cultures were incubated at 37°C for 4hrs while shaking; the culture media of untreated HCEC served as the control. At the end of the incubation, 10µl of serial dilutions of each reaction mixture were spread evenly over the surface of nutrient broth plates using sterile plastic spreaders. After incubation at 37°C for approximately 16hrs, a digital image was captured of each plate with an Alpha Imager documentation system (Alpha Innotec). The number of colonies was counted by using the colony count software of the Alpha Imager. The data were analyzed by Student’s t-test with P ≤0.05 being considered significant.

We observed that the culture media from TLR agonist treated cells did indeed have significant antimicrobial activity against PA. Therefore, to determine if hBD-2 and LL-37 peptides were responsible for this activity a series of additional experiments was performed. Previous studies have shown that in the presence of salt, the antimicrobial activity of hBD-2 and LL-37 against PA is reduced. In 150mM NaCl, the EC50 for hBD-2 against PA (ATCC strain 27853) is decreased by 13 fold (Huang et al., 2007b) whereas LL-37 appears to be less susceptible to the effects of salt with only a 3.5 fold reduction of the EC50 (Huang et al., 2006). Because of this effect the antimicrobial activity of the peptides in primary HCEC culture media which contains 130mM NaCl was determined. Here, fresh EpiLife media was incubated with 200cfu/ml of PA and either 3µg/ml or 3ng/ml of purified synthetic LL-37, or 10µg/ml of recombinant hBD-2 or media alone and the antimicrobial activity was determined. In keeping with the previous observations, the data showed that LL-37 retained more antimicrobial activity when added to culture media than hBD-2. To determine if LL-37 was responsible for the antimicrobial activity against PA, the growth media following TLR agonist treatment was incubated with an antibody against LL-37 which binds to the functional C-terminal end of the peptide and abolishes its antimicrobial activity. In these experiments, primary HCEC were treated with either a combination of TLR3, 5, 6/2 agonists or media alone for 20hrs. The culture media was collected and centrifuged (1400g for 2 min) to remove cell debris and then incubated with either preimmune rabbit serum or rabbit anti-human LL-37 C-terminal antibody (donated by Dr. R.I. Lehrer) diluted 1 to 200 at 4°C overnight and then the antimicrobial activity against PA was determined as described above. The data were analyzed by Student’s t-test with P ≤0.05 being considered significant.

Immunoblot Analysis for hBD-2 and LL-37 and hBD-2 ELISA

Primary HCEC were treated with media or a combination of TLR3, 5 and 6/2 agonists and a portion of the culture media was then blotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane using a microfiltration apparatus (Biodot; Irvine, CA) to detect the presence of hBD-2 (McDermott et al., 2001) or LL-37 (Huang et al., 2006) as previously described. The remaining cells were lysed in 100µl of ice cold RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors (Roche; Nutley, NJ) and scraped free from the dish to ensure complete removal of all cells. Briefly for hBD-2 immunoblotting, after loading the sample, the membrane was then fixed in 10% formalin for one hour at room temperature. For both hBD-2 and LL-37 immunoblots, nonspecific binding sites were blocked by incubation in 5% blotto in TBS containing 0.05% Tween (TTBS). Membranes were then incubated with primary antibody against either hBD-2 (donated by Dr. T. Ganz) diluted 1 in 1000 or LL-37 (donated by Dr. R.I. Lehrer) diluted 1 to 5000 in 5% blotto with TTBS. After an overnight incubation at 4°C the membranes were then incubated with a horseradish peroxidase linked second antibody and immunoreactivity was visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL Plus Western Blot Detection kit; GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). The results were documented with an Alpha Imager documentation system. A standard curve was generated by plotting the density of the peptide standard versus concentration to determine the amount of LL-37 peptide in the samples. A portion of the culture media and the lysate were also collected as described above and analyzed for the presence of hBD-2 with an ELISA kit (Peprotech; Rocky Hill, NJ) as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Results

TLR expression by corneal and conjunctival cells

Owing to discrepancies between data from previous studies, possibly because different cell sources (cell lines vs. primary culture) were used, we sought to determine TLR mRNA expression in our particular epithelial cell lines and cultures and extended the study to other corneal cells. The results are summarized in table 1. TLR1-3, 5-6 and 9 were expressed in all three of the sources of HCEC. TLR4 mRNA was only detected in SV40 HCEC by RT-PCR but in subsequent experiments low levels of expression were detected in primary HCEC by real-time PCR (data not shown). Expression of TLR7 mRNA was detected in SV40 HCEC and primary cultured HCEC but not in freshly scraped cells. TLR10 was not expressed by any of the HCEC with the exception of a weak expression in two of the five SV40 HCEC cultures that were tested. Stromal keratocytes expressed TLR1-7 and TLR9 and 10 whereas cultured corneal fibroblasts, the keratocyte repair phenotype, similarly expressed TLR1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9 and 10 but did not express TLR2 and TLR5. IOBA-NHC cells expressed TLR1-4, 6-7 and TLR9 and conjunctival cells collected by impression cytology expressed TLR1-7, and TLR9-10. TLR8 was not detected in any of the corneal or a conjunctival cell tested but was detected and its sequenced confirmed in human spleen samples, the positive control.

Table 1.

TLR 1–10 mRNA expression in various ocular surface cells. Positive mRNA expression is denoted by a plus (+) sign while negative mRNA expression was intentionally left blank. The table is representative of samples from 3–5 donors or 3–5 passages for cell lines. Vary= two of the five SV40 HCEC cultures were positive (for all the other cell types, all of the samples tested were either positive or negative). HCEC= human corneal epithelial cells, CIC=conjunctival impression cytology, IOBA NHC= Normal human conjunctival epithelial cells.

| TLR mRNA Expression | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Type | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| Scraped Epi | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Primary HCEC | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| SV40 HCEC | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | vary | |

| CIC | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| IOBA NHC | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| Keratocytes | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Fibroblasts | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||

As previous studies have shown that TLR mRNA expression is reflective of protein expression the latter was “spot checked” in a limited number of samples. TLR3, 5 and 9 protein expression was examined in human corneas and in cultured cells by immunostaining and for TLR3 and 9 by flow cytometry. In the human corneal epithelium, TLR3 (figure 1A) and 9 (figure 1C) were expressed throughout the entire corneal epithelium, whereas TLR5 (figure 1B) was expressed in basal and some wing cells but not in the superficial layers. TLR5 and 9, but not TLR3, were also expressed by the stromal keratocytes and the endothelium. TLR3 and 9 protein expression was confirmed in HCEC SV40 cells by flow cytometry and therefore was not further examined by immunostaining (figure 2A). Cultured fibroblasts did not significantly express TLR3 and weakly expressed TLR9 as determined by flow cytometry (figure 2B). Since TLR3 was detected by RT-PCR but not by flow cytometry, TLR3 and 9 expression was further examined by immunostaining (figure 2C). This confirmed TLR9 expression and also showed there was no significant expression of TLR3 suggesting that the protein is either being degraded, its production is inhibited, or is not expressed in sufficient amounts to be detected by our methodologies.

Figure 1.

TLR3 (A), TLR5 (B), and TLR9 (C) expression in the human cornea. Montages encompassing the epithelium (epi), stroma and endothelium (endo) were prepared from central cornea cryosections stained for TLRs. In each section the top panel is the isotype control, the middle panel is tissue stained for the specific TLR and the bottom two images are enlarged to show detail for the epithelium and stroma. Blue fluorescent DAPI was used to stain the nuclei. All images were taken at 200X magnification. Scale bars (shown only for TLR3) represent 40 microns. Results are representative of 3–4 corneas.

Figure 2.

TLR3 and 9 protein expression in SV40 HCEC by flow cytometry (A) or in primary cultured fibroblasts by flow cytometry (B) and immunostaining (C). Flow cytometry histograms show the relative fluorescence on the x-axis and the number of events (cell count) on the y-axis. Dashed line represents the isotype control antibody while the solid line represents the specific TLR. Fibroblasts were immunostained for TLR3 (green) and TLR9 (red) with DAPI (blue) being used to stain the nuclei (C). Isotype controls were IgM and IgG for TLR3 and 9 respectively. Images were taken at 200X magnification. The data are representative of 2–3 experiments.

TLR agonists modulate hBD-2 and hCAP-18 mRNA expression in ocular surface cells

Ocular surface cells were exposed to various TLR agonists and hBD-2 and hCAP-18, the precursor to LL-37, mRNA expression was determined by RT-PCR. As shown in figure 3A, TLR1/2, 3, 4, 5 and 6/2 agonists upregulated the expression of hBD-2 in SV40 HCEC while in IOBA-NHC cells onlyTLR1/2 and 6/2 agonists upregulated the expression of hBD-2 above baseline with the activation of TLR6/2 stimulating the most robust response. In all samples tested, the upregulation of hBD-2 with TLR agonists was as effective as the positive control, IL-1β, with the exception of LPS which only modestly upregulated hBD-2 in SV40 HCEC. IL-1β and TLR agonists had no effect on hBD1 and hBD3 mRNA expression in all cell types tested (data not shown).

Figure 3.

hBD-2 and hCAP-18 mRNA expression in response to TLR agonists in ocular surface cells. SV40 HCEC and IOBA-NHC cells were treated with various TLR agonists: Pam3CSK4 (TLR 1/2), HKLM (TLR 2), PolyI:C (TLR 3), LPS E. coli K12 (TLR 4), Flagellin S. typhimurium (TLR 5), FSL1 (TLR 6/2), Imiquimod (TLR 7), ODN2006 (TLR 9), or 10ng/ml of IL-1β or serum free media (M) for 24 hours. (A) Ethidium bromide stained agarose gel for hBD-2 and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Real-time PCR was performed to determine the relative quantity of hBD-2 (B) and hCAP-18 (C) mRNA in primary HCEC. The data are representative of 2–4 independent experiments.

Since many primary HCEC show a baseline expression of hBD-2 and hCAP-18 mRNA, real-time PCR was performed to better quantitate any change in expression above baseline following TLR activation in these cells. Agonists for TLR3, 5 and 6/2 upregulated hBD-2 mRNA expression (figure 3B) while only the TLR3 agonist was able to upregulate hCAP-18 expression in primary HCEC (figure 3C). hCAP-18 mRNA expression was not modulated by TLR agonists as determined by real-time PCR in either IOBA-NHC or SV40 HCEC under the conditions tested (data not shown, n=2).

TLR agonists modulate hBD-2 and LL-37 protein expression in primary HCEC

Immunoblot analysis was performed to determine hBD-2 and LL-37 peptide secretion by primary HCEC treated with a combination of TLR 3, 5 and 6/2 agonists. Levels of LL-37 secreted in to the culture media were estimated by semiquantitative immunoblotting (n=2). As depicted in figure 4A, TLR agonist treatment increased the level of LL-37 and after accounting for the dilution factor, the concentration increased from 1.86 +/− 0.07 to 3.02 ±1.02 ng/ml or by 1.63 fold (figure 4B). In regards to hBD-2 peptide, TLR agonist treatment modestly increased hBD-2 peptide in the culture supernatant and cell lysate compared to the untreated control as determined by immunoblot (data not shown). To quantify the protein levels, hBD-2 protein was detected by ELISA in both the culture supernatant and cell lysate. In the culture supernatant, there was a significant (P<0.05) increase in hBD-2 peptide concentration from 0.102 ± 0.011ng/ml to 1.47± 0.66ng/ml (14.4 fold increase) following TLR agonist treatment (figure 4C). While in the cell lysate, TLR agonist treatment significantly increased hBD-2 levels by 15.2 ± 5.3 fold and hBD-2 concentration increased from 0.138 ± 0.06 to 2.23± 1.51ng/ml (figure 4C).

Figure 4.

TLR agonists upregulate LL-37 and hBD-2 peptide production as detected by immunoblotting and ELISA respectively. Primary HCEC were treated for 20 hours with either media alone or a combination of TLR 3, 5 and 6/2 agonist which upregulate hBD-2 or LL-37 mRNA. (A) Representative immunoblot for LL-37 secreted in to the culture media (n=2). (B) The pixel intensity of each dot was used for semi-quantitative analysis. (C) hBD-2 protein production was quantitated in the culture media and cell lysate by an ELISA, n=3. A P-value of <0.05 (*) was considered to be statistically significant by Student’s t-test.

Modulation of TLR mRNA expression in ocular surface cells

Previous studies have shown that the activation of TLR2 (Kumar et al., 2006) and TLR3 (Ueta et al., 2005) modulates their own expression in human corneal epithelial cells, therefore we examined if a similar effect would occur following the activation of TLR4, 5, and 9 in various ocular surface cells. Since primary HCEC and IOBA-NHC did not express detectable amounts of TLR4 and TLR5 respectively we did not examine a change in their expression following agonist treatment for these specific TLRs. We found TLR activation by various TLR agonists did not modulate TLR mRNA expression in our cells (data not shown). More specifically in primary HCEC, flagellin and ODN2006 were not able to modulate TLR5 and TLR9 mRNA expression respectively (n=2) and LPS and ODN2006 did not modulate TLR4 and TLR9 mRNA expression in IOBA-NHC cells (n=2). Furthermore activation by LPS, flagellin, and ODN2006 did not modulate TLR4, 5, and 9 mRNA expression respectively in SV40 HCEC (n=3).

To determine if antimicrobial peptides modulate TLR expression, ocular surface cells were cultured with 3µg/ml hBD-2 or 5µg/ml LL-37, concentrations comparable to those used in previously published studies examining the functional activity of these peptides (Huang et al., 2006, 2007b; Li et al., 2009). RT-PCR was performed to determine TLR 1-10 mRNA expression and is represented in table 2. The general trend was for no change or a downregulation of TLRs, however, due to variability among the samples statistical significance was achieved in only three instances. In IOBA-NHC cells, LL-37 significantly downregulated the expression of TLR9 by 12.5 ± 4.3% (P≤ 0.05), in SV40 HCEC, TLR7 mRNA was downregulated by hBD2 by 11 ± 1.40% (P≤ 0.05) and in primary HCEC, TLR5 mRNA was downregulated by LL-37 by 34 ± 6.5% (P≤ 0.05), n=3.

Table 2.

SV40 HCEC, IOBA-NHC or primary HCEC were treated with either 3µg/ml of hBD-2, 5µg/ml of LL-37 or serum-free (SV40 and IOBA-NHC) or supplement-free (primary HCEC) media for 24 hours. TLR1-10 and GAPDH mRNA expression was then determined. The pixel intensity of bands on the gels was measured and normalized to GAPDH, the internal control. Data are the percent change ± standard deviation from control untreated cells.

| Cell Type Treatment |

TLR 1 | TLR2 | TLR3 | TLR4 | TLR5 | TLR6 | TLR7 | TLR9 | TLR10 (n=2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOBA NHC | |||||||||

| a.) hBD-2 | −3.7 ± 8.2% | 11 ± 29% | −7.6 ± 2.6% | −6.0 ± 2.8% | NA | −3.6 ± 7.9% | 3 ± 3.5% | −16 ± 12% | NA |

| b.) LL-37 | −7.6 ± 17% | −9.0 ± 25% | −18 ± 12% | 0.3 ± 23% | NA | −11 ± 7.3% | −25 ± 21% | *−12.5 ±4.3% | NA |

| SV40 HCEC | |||||||||

| a.) hBD-2 | 3.0 ± 4.2% | 17 ± 22% | −2.0 ± 5.1% | −23 ± 43% | 21 ± 15% | 2.0 ± 0.9% | *−11 ±1.40% | −13 ± 13% | 24 ± 4.8% |

| b.) LL-37 | 0.0 ± 4.6% | −9.0 ± 14% | −1.0 ± 1.6% | −4.0 ± 23% | −5.0 ± 6.3% | −28 ± 44% | −22 ± 15% | −7.0 ± 7.7% | −14 ± 22% |

| Primary HCEC | |||||||||

| a.) hBD-2 | 0.0 ± 6.4% | −7.0 ± 2.6% | −1.0± 18% | NA | −5.0 ± 20% | −8.0 ± 7.2% | −13 ± 12% | −3.0 ± 7.5% | NA |

| b.) LL-37 | −24 ± 23% | −18 ± 17% | 29 ± 27% | NA | *−34 ± 6.5% | −32 ± 38% | −20 ± 20% | 19 ± 8.3% | NA |

The data were analyzed by Student's t-test with values of P ≤ 0.05 being considered significant (*)

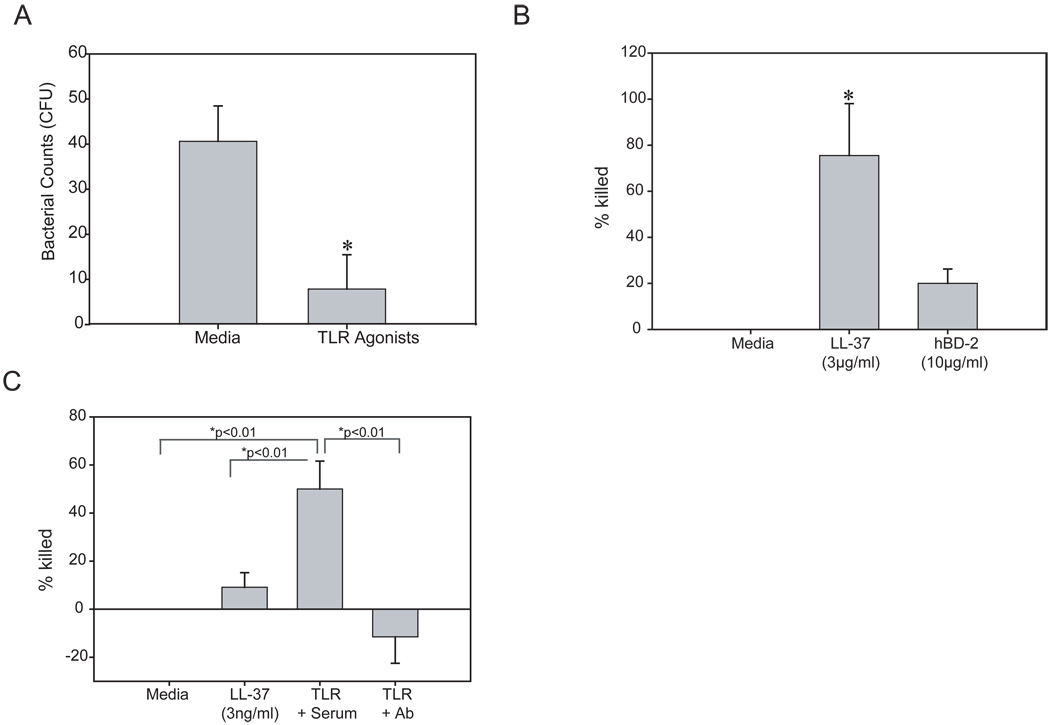

Conditioned media from TLR agonist challenged HCEC possesses antimicrobial activity that is mediated by LL-37

Since a combination of TLR3, 5 and 6/2 agonists upregulated hBD-2 and LL-37 in primary HCEC, we next examined if the culture media from these cells had antimicrobial activity against PA. As shown in figure 5A, we found that culture media from agonist treated cells was able to significantly kill PA as determined by a reduction in PA colonies compared to the media treated control (P< 0.01, n=4). As noted above previous studies have shown reduced antimicrobial activity in the presence of salt (Huang et al., 2006; 2007b) therefore we studied the antimicrobial effect of synthetic LL-37 and recombinant hBD-2 in the presence of EpiLife culture media which contains 130mM NaCl. Under these conditions 3µg/ml LL-37 was able to significantly kill over 75.5 ± 22.5% of the bacteria, whereas at over three times the concentration, hBD-2 was only able to kill 19.9 ± 6.2% of the bacteria. Based on these findings we then sought to determine if LL-37 secreted in to the culture media following TLR agonist treatment was the key component responsible for killing PA. The antimicrobial activity of LL-37 was examined at 3ng/ml, to determine if there was any activity at the concentration found in the media following TLR agonist stimulation. At this concentration, LL-37 was able to modestly kill PA by 9.1 ± 6.11% (figure 5C). Furthermore, following TLR agonist treatment, blocking LL-37 with a C-terminal antibody significantly reduced the bacterial count beyond baseline (−11.5 ± 11.0%) (figure 5C), while significant killing (50 ± 11.6%) of PA was still achieved when the culture media was treated with pre-immune rabbit serum prior to antimicrobial assays compared to media alone and 3ng/ml of LL-37.

Figure 5.

Antimicrobial activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) of primary HCEC treated with TLR agonist cocktail is dependent on LL-37. (A) The antimicrobial activity of culture media from primary HCEC treated with TLR 3, 5 and 6/2 agonists was determined by a colony count assay. (B) To determine the activity of AMPs in culture media, synthetic LL-37 (3µg/ml) or rhBD-2 (10µg/ml) were incubated with culture media and PA and the percent bacteria killed was calculated with media treated representing no killing. (C) PA were incubated with culture media alone, synthetic LL-37 (3ng/ml) or with media from primary HCEC treated with TLR3, 5 and 6/2 agonists which had then been incubated with preimmune rabbit serum (serum) or a LL-37 blocking antibody (Ab) and the percent bacteria killed was calculated. The figures are representative of 2–6 independent experiments. When comparing two groups, an unpaired Student’s t test was used and a P-value of <0.05 (*) was considered to be statistically significant. For all others, a P-value <0.01 was considered to be significant by ANOVA with Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons.

Discussion

The results from the present study show that TLRs are expressed not only by cultured (cell lines and primary) HCEC but also by freshly isolated HCECs from normal human cadaver corneas, stromal keratocytes and fibroblasts, conjunctival impression cytology samples and IOBA-NHC conjunctival epithelial cells. We have also shown that the activation of specific TLRs in primary HCECs upregulates hBD-2 and LL-37 mRNA and peptide expression and that LL-37 is more effective than hBD-2 in killing PA. Furthermore we also found that the activation of specific TLRs does not modulate their own expression while hBD-2 and LL-37 peptides are able to modestly downregulate the expression of some TLRs in human corneal and conjunctival epithelial cells.

While TLR expression has been examined in ocular surface cells by others, to our knowledge, this is the first study to comprehensively examine TLR expression simultaneously in several ocular surface and corneal stromal cells. Here TLR expression was examined in three sources of HCEC, cells scraped from donor corneas, primary cultured, and a SV40 transformed cell line. As stated previously, TLR1, 2, 3, 5, 6, and 9 were expressed by all three sources of cells tested while only SV40 HCEC expressed TLR4 and TLR7, however, using real-time PCR, low levels of TLR4 were detected in primary HCECs by real-time PCR (data not shown). As discussed in the results section, a few samples were selected to correlate protein production with mRNA expression. We confirmed the expression of TLR3, 5 and 9 in human corneal epithelium by immunostaining tissue sections, and that of TLR3 and 9 in SV40 HCEC by flow cytometry. Notably TLR5 was only expressed by basal and wing epithelial cells which is in agreement with Hozono et al. (2006) who suggested that this distribution may contribute to the immunosilent nature of the normal cornea. Unlike most other TLRs, TLR10 was not reproducibly expressed by HCECs from any source in our study. In general, our data are in agreement with previously published studies. Wu et al. (2007) found that human corneal epithelial samples collected from patients undergoing photorefractive keratotomy, in general, strongly expressed TLR1, 2, 3, 5, 6 and 9 and weakly expressed TLR4, 7 and 8 if at all. Jin et al. (2007) observed expression of all ten TLRs in donor cornea biopsies with TLR1, 2, 3, 4 and 6 having the highest and TLR 7, 8 and 9 the lowest levels. These previously published observations indicate a variable expression pattern for several TLRs which may account for our results with TLR4 and 7. The SV40 HCEC cell line consistently expressed TLR1-7 and 9, and all of these TLRs have been detected in studies of normal corneal epithelial tissue, suggesting that this cell line is a suitable model for studying the role of these TLRs at the ocular surface.

Few studies have specifically addressed TLR expression in corneal layers other than the epithelium. Here we investigated TLR expression in corneal stromal cells from cadaver donors, freshly isolated keratocytes and cultured stromal fibroblasts (repair phenotype keratocytes). Such a comprehensive analysis of keratocyte TLR expression has not been published to our knowledge. Previously, Ebihara et al. (2007) reported that keratocytes and cells they referred to as corneal myofibroblasts expressed TLR2 and 4 mRNA but only the myofibroblasts expressed TLR3 and 9. Furthermore functional studies have shown that TLR4 (Kumagai et al., 2005) activation in corneal fibroblasts results in cytokine secretion. Here, we found that keratocytes expressed TLR1-7, 9, and 10 mRNA whereas cells that had transformed into the fibroblast phenotype no longer expressed TLR2 and TLR5 mRNA. The lack of TLR2 expression in corneal fibroblasts was unexpected as previous studies have shown TLR2 and TLR 4 mRNA expression in primary cultured corneal fibroblasts by real-time PCR (Gao et al., 2009; Jin et al., 2009). Our study may have missed trace amounts of mRNA expression that may have been detectable by the real-time RT-PCR method the authors used or the lack of expression may be reflective of donor variability. In human cornea sections, immunostaining revealed that TLR5 and TLR9 were expressed by what appear to be corneal keratocytes based on the number and distribution of cells stained but additional immunostaining was not performed to distinguish them from resident immune cells. This experiment also showed that corneal endothelial cells express TLR5 and 9. Although both keratocytes and cultured fibroblasts expressed TLR3 mRNA, immunostaining and flow cytometry could not confirm actual protein expression for this TLR by these cells. As stromal fibroblasts are only present at times when the cornea is compromised due to injury and inflammation, a change in TLR expression may be beneficial or destructive to the ocular surface in modulating inflammation. A reduction in expression of individual TLRs accompanying the transition from keratocyte to fibroblast as we observed here may help prevent further undue inflammation in the stroma however, it may also leave the stroma with a reduced ability to detect and remove pathogens rendering it more susceptible to microbial keratitis.

Unlike the other TLRs, little is known regarding TLR10 expression and function. A recent study found that TLR10 requires TLR2 to recognize microbial lipopeptide but it lacks the downstream signaling that is shared with other TLR2 family members (Guan et al., 2010) which calls in to question its function. To our knowledge, ours is the first study to examine TLR10 expression in various ocular surface cells. Previous studies (Jin et al., 2007; 2008) have found TLR10 expression in full thickness penetrating keratoplasty biopsies but attempts were not made to localize its expression to specific cell types. Here we found that TLR10 expression was unique to freshly isolated stromal keratocytes and fibroblasts. While keratocytes form the majority of stromal cells, several immune cells, such as dendritic cells and monocytes have recently been found in the stroma (Hamrah and Dana, 2007; Mayer et al., 2007) which may serve as the source of TLR10 mRNA that we detected. However, the likely hood of this being the case is small as immune cells constitute only a small portion of the total cells in the normal cornea and of these, TLR10 is known to be expressed on dendritic cells (Hasan et al., 2005) but not on monocytes (Hornung et al., 2002). Further, immune cells are often depleted from cadaver corneas when placed into storage media (Jeng, 2006) and would most likely not survive or would be washed away when placed in culture with the keratocytes. Thus, our study suggests that TLR10 expression in the cornea is unique to keratocytes and fibroblasts, but its exact role and function remains unknown.

In regards to TLR expression in the conjunctiva, Bonini et al. (2005) have found that the healthy conjunctival epithelium and stroma expresses TLR2, 4 and 9 mRNA and protein, while Cook et al. (2005) observed cell surface expression of TLR2 in cultured conjunctival epithelial cells and in conjunctival impression cytology samples from human subjects with atopic keratitis and allergic conjunctivitis, but not in patients without ocular allergies. Li et al. (2007) have reported that TLR1, 2, 3, 5 and 6 mRNA were expressed in conjunctival and limbal epithelial samples, whereas the expression of TLR4 and 9 mRNA was variable and TLR7, 8 and 10 mRNA were not detected. In addition, they also reported TLR1-6 and TLR 9 protein to be expressed in human limbal and conjunctival epithelial cells by western blot. In agreement with the general findings of these studies, we detected TLR 1-6 and 9 mRNA in conjunctival impression cytology samples but we were also able to detect the presence of TLR7 and TLR10. The IOBA-NHC cell line showed a similar pattern of expression with the exception that it did not express TLR5 and TLR10; therefore this cell line might serve as a suitable model for investigating some TLRs in the conjunctiva in future studies. Interestingly, a principal component analysis has shown that IOBA-NHC are most similar to primary human conjunctival epithelial (PCEC) cells compared to another conjunctival epithelial cell line, but that TLR4 protein levels were reduced in the IOBA-NHC cells compared to PCEC (Tong et al., 2009) which should be considered when using this cell-line to investigate TLR4 in future studies.

In addition to the known role in surveillance for microbial pathogens, TLRs at the ocular surface modulate the expression of antimicrobial peptides providing additional protection to ward off microorganisms. Although some studies have examined the relationship between TLR activation and antimicrobial peptide expression in human corneal epithelial cells, very little is known about this relationship in the conjunctiva. Further, to our knowledge this is the first study to report a concurrent comparison of antimicrobial peptide expression across the whole range of TLR activation in ocular surface epithelial cells. With the exception of TLR2, 7 and TLR9, all the TLR agonists were able to modulate the expression of antimicrobial peptides depending on the cell type using the manufacturer’s recommended concentrations. A previous study has shown that TLR2 and 9 agonists, used at the same concentrations in this study, can modulate functions of other cell types (Rowlett et al., 2008). However, the possibility remains that the concentrations/treatment times of the TLR2, 7 and 9 agonists were not optimal for the cells examined in this study. In these studies we found fewer agonists stimulated hBD-2 expression in the IOBA-NHC cells than in the SV40-HCECs. At least in the case of TLR4, this may be attributed to the lack of essential costimulatory molecules required for activation in IOBA-NHC as TLR4 activation is dependent on complex formation with LBP, CD14 and MD-2, and unresponsiveness to LPS has been attributed to lack of these in some studies (Blais et al., 2005). Alternatively, Li et al. (2007) detected TLR4 in the conjunctival epithelium by immunohistochemistry but these cells did not demonstrate secretion of proinflammatory cytokines in response to LPS even in the presence of MD-2 and exogenous LBP and CD14. The authors suggested that ocular surface cells may require priming with IFNγ or TNFα which is required by other mucosal epithelia cells to render them responsive to LPS treatment.

Activation of TLR3, 5 and 6/2 stimulated hBD-2 mRNA expression in both primary and SV40 HCEC and TLR1/2 and 4 activation also stimulated hBD-2 mRNA expression in SV40 HCEC (TLR4 agonist stimulation was not examined in primary HCEC as these cells lacked significant TLR4 mRNA expression). Previously, Kumar et al., (2007) found that PA, a TLR4 and 5 agonist, induced the upregulation of hBD-2 in a human corneal-limbal cell line while Kumar et al. (2006) and Li et al. (2008) reported that a human corneal-limbal cell line and primary HCEC respond to TLR1/2 and TLR2 agonist by expressing hBD-2 mRNA and secreting hBD-2 into the culture media. Although data with our SV40 HCEC line is in agreement with this, in our hands primary HCEC were unresponsive to TLR1/2 agonist stimulation. This discrepancy could result from donor variation or variations in experimental protocols, as we used freshly isolated primary HCEC at passage one and a lower concentration of Pam3CSK4 (1µg/ml) whereas they used primary HCEC at passage three and a higher concentration of Pam3Cys (10µg/ml), a similar agonist but from a different manufacturer.

hCAP 18, the precursor to LL-37, was found to only be upregulated in response to TLR3 agonist treatment in primary HCECs after 24 hours and as early as 30 minutes following treatment (unpublished observation). However in all other cell types that we tested there was no significant change in hCAP 18 mRNA expression following TLR agonist treatment. This was a surprising result as Kumar et al. (2007) and Li et al. (2008) found that freshly isolated PA flagellin or SA extract were able to increase LL-37 mRNA and protein expression in a cornea-limbal epithelial cell line. However, here we stimulated freshly isolated primary HCEC with commercially available flagellin from S. typhimurium, a common pathogen of the intestine, and it is possible that this ligand, which we have shown does upregulate hBD-2, is not optimal for upregulating LL-37.

We also examined hBD-2 and LL-37 protein levels and the antimicrobial activity of the culture media supernatant following cell stimulation with a cocktail of TLR3, 5 or TLR6/2 agonist. Activation of these TLRs stimulated the secretion of low levels (in the nanogram range) of both hBD-2 and LL-37 into the culture media. Such concentrations are in keeping with hBD-2 levels in tears (329±154pg/ml, Redfern & McDermott unpublished observation) and cornea (Garreis et al., 2010). Notably, the culture media for agonist treated cells had significant antimicrobial activity against PA and additional experiments suggest that this antimicrobial activity is primarily attributable to LL-37.

Previous studies have shown that hBD-2 is more salt sensitive than LL-37 (Huang et al., 2006; 2007b, Starner et al., 2005) implying greater activity of the latter in a physiological environment. Here we confirmed superior antimicrobial activity of LL-37 in experiments carried out in culture media rather than the phosphate buffer of a standard antimicrobial assay. Under these conditions, LL-37 was significantly more effective at killing PA than hBD-2 even using a third of the concentration of hBD-2. Furthermore, the antimicrobial activity of the culture media following TLR agonist treatment was completely abolished in the presence of an antibody that blocks LL-37. It is interesting to consider that 3ng/ml of synthetic LL-37 was significantly less effective at killing PA compared to the culture media from primary HCEC that were stimulated with the TLR agonist cocktail. An obvious explanation for this discrepancy would be that LL-37 is not the only factor secreted with antimicrobial activity. However the experiments with the LL-37 antibody, which were properly controlled with pre-immune serum, argue against this. Also as discussed, while hBD-2 is present it does not have significant antimicrobial activity under the assay conditions. One possibility is that, as has been shown for skin, LL-37 is further processed to smaller fragments which also have potent antibacterial activity and which would be blocked by the antibody (Murakami et al., 2004). Taken together, these results suggest that LL-37 is responsible for killing PA and may be a novel therapeutic option to reduce the risk of microbial keratitis. In support of this, LL-37 has antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive (S. aureus and S. Epidermidis) and Gram-negative (PA) organisms that are often associated with bacterial keratitis and contact lens associated keratitis. Contact lens wear reduces PA induced upregulation of hBD-2 in HCEC in vitro (Maltseva et al., 2007) and the antimicrobial activity of hBD-2 against PA is reduced by human tears (Huang et al., 2007b) by up to 90% while that of LL-37 is not impacted nearly as much (Huang et al., 2007b).

Previous studies have shown that the activation of TLR2 (Kumar et al., 2006), TLR3 (Ueta et al., 2005) and TLR4 (Zhao and Wu, 2008) modulates their own mRNA expression in human corneal epithelial cells after a short time period of up to six hours but later time points were not examined. Here we observed that expression of TLR4, 5 and 9 mRNA expression was not modulated by agonist activation after 24 hours. These observations suggest that TLR activation may lead to an early transient increase in TLR expression after six hours that returns to baseline by 24 hours.

As TLR activation results in the production of AMPs, we sought to determine if AMPs can then modulate TLR expression suggesting either a negative or positive feedback loop. In this study, 24 hours exposure to hBD-2 and LL-37 modestly downregulated the expression of some TLRs in human corneal and conjunctival epithelial cells. A previous study has also suggested that TLR expression can be modulated by some defensins, although as this was conducted in vivo it is unclear if this was a direct or indirect effect (Wu et al. 2009a). Other studies have shown that some defensins use TLRs to modulate mammalian cell activities (Biragyn et al., 2002; Funderburg et al., 2007). These findings suggest that the activation of TLRs stimulates an antimicrobial response by the upregulation of antimicrobial peptides which in turn may serve as an endogenous ligand for TLRs to modulate their own expression. Since hBD-2 and LL-37 are expressed at the ocular surface in response to injury and proinflammatory cytokines, a downregulation of TLRs in response to AMPs might provide the ocular surface with a reduced risk for severe inflammation. However the small changes of TLR mRNA expression observed here may not be physiologically relevant on the ocular surface due to the redundant nature of these receptors and the high concentrations (relative to the levels secreted in to the culture media) of hBD-2 and LL-37 used in these studies.

Overall, our results show that the ocular surface expresses a variety of TLRs which allows the rapid detection and killing of potential pathogens such as PA. TLR activation by their respective agonists resulted in the production of antimicrobial peptides, in particular LL-37, which in turn may increase the spectrum of antimicrobial activity to ward off invading pathogens

Toll-like receptors (TLR) are expressed by various ocular surface cells.

TLR agonists stimulate hBD-2 and LL-37 secretion and lead to bacterial killing.

Antimicrobial activity is primarily attributed to LL-37.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Heartlands Lions Eye Bank for supplying the donor corneas. We would also like to thank Drs. T. Ganz (University of California, Los Angeles) and R.I. Lehrer (University of California, Los Angeles) for supplying the hBD-2 and LL-37 antibodies respectively and Dr. Alan Burns (University of Houston) for his assistance with the Delta Vision Image System. The IOBA-NHC cells and SV40 HCEC were kindly donated by Drs. Diebold (University Institute of Applied Ophthalmobiology) and Araki Sasaki (Kumamoto University, Japan) respectively.

Grant information: This research was supported by EY013175 (AMM), EY018113 (RLR) and EY007551 (University of Houston, College of Optometry CORE Grant). RLR was partially supported by a William C. Ezell Fellowship from the American Optometric Foundation and a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (EY7024-25).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aarbiou J, Ertmann M, van Wetering S, et al. Human neutrophil defensins induce lung epithelial cell proliferation in vitro. J.Leukoc.Biol. 2002;72:167–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexopoulou L, Holt AC, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA. Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-kappaB by Toll-like receptor 3. Nature. 2001;413:732–738. doi: 10.1038/35099560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Befus AD, Mowat C, Gilchrist M, Hu J, Solomon S, Bateman A. Neutrophil defensins induce histamine secretion from mast cells: mechanisms of action. J. Immunol. 1999;163:947–953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler B. TLR4 as the mammalian endotoxin sensor. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2002;270:109–120. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-59430-4_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blais DR, Vascotto SG, Griffith M, Altosaar I. LBP and CD14 secreted in tears by the lacrimal glands modulate the LPS response of corneal epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:4235–4244. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonini S, Micera A, Iovieno A, et al. Expression of Toll-like receptors in healthy and allergic conjunctiva. Ophthalmol. 2005;112:1528–1534. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biragyn A, Ruffini PA, Leifer CA, Klyushnenkova E, Shakhov A, Chertov O, Shirakawa AK, Farber JM, Segal DM, Oppenheim JJ, Kwak LW. Toll-like receptor 4-dependent activation of dendritic cells by beta-defensin 2. Science. 2002;298:1025–1029. doi: 10.1126/science.1075565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaly YV, Paleolog EM, Kolesnikova TS, Tikhonov II, Petratchenko EV, Voitenok NN. Neutrophil alpha-defensin human neutrophil peptide modulates cytokine production in human monocytes and adhesion molecule expression in endothelial cells. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 2000;11:257–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chertov O, Michiel DF, Xu L, Wang JM, Tani K, Murphy WJ, Longo DL, Taub DD, Oppenheim JJ. Identification of defensin-1, defensin-2, and CAP37/azurocidin as T-cell chemoattractant proteins released from interleukin-8-stimulated neutrophils. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:2935–2940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.2935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook EB, Stahl JL, Esnault S, Barney NP, Graziano FM. Toll-like receptor 2 expression on human conjunctival epithelial cells: a pathway for Staphylococcus aureus involvement in chronic ocular proinflammatory responses. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005;94:486–497. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diebold SS, Kaisho T, Hemmi H, Akira S, Reis e Sousa C. Innate antiviral responses by means of TLR7-mediated recognition of single-stranded RNA. Science. 2004;303:1529–1531. doi: 10.1126/science.1093616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebihara N, Yamagami S, Chen L, Tokura T, Iwatsu M, Ushio H, Murakami A. Expression and function of toll-like receptor-3 and -9 in human corneal myofibroblasts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:3069–3076. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fini ME. Keratocyte and fibroblast phenotypes in the repairing cornea. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 1999;18:529–551. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(98)00033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funderburg N, Lederman MM, Feng Z, Drage MG, Jadlowsky J, Harding CV, Weinberg A, Sieg SF. Human-defensin-3 activates professional antigen-presenting cells via Toll-like receptors 1 and 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:18631–18635. doi: 10.1073/PNAS.0702130104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garreis F, Schlorf T, Worlitzsch D, Steven P, Bräuer L, Jäger K, Paulsen FP. Roles of human beta-defensins in innate immune defense at the ocular surface: arming and alarming corneal and conjunctival epithelial cells. Histochem Cell Biol. 2010;134:59–73. doi: 10.1007/s00418-010-0713-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao T, Lin Z, Jin X. Hydrocortisone suppression of the expression of VEGF may relate to toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and 4. 2009. Curr Eye Res. 2009;34:777–784. doi: 10.1080/02713680903067919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon YJ, Huang LC, Romanowski EG, et al. Human cathelicidin (LL-37), a multifunctional peptide, is expressed by ocular surface epithelia and has potent antibacterial and antiviral activity. Curr Eye Res. 2005;30:385–394. doi: 10.1080/02713680590934111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y, Ranoa DR, Jiang S, Mutha SK, Li X, Baudry J, Tapping RI. Human TLRs 10 and 1 share common mechanisms of innate immune sensing but not signaling. J Immunol. 2010;184:5094–5103. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamrah P, Dana MR. Corneal antigen-presenting cells. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2007;92:58–70. doi: 10.1159/000099254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan U, Chaffois C, Gaillard C, Saulnier V, Merck E, Tancredi S, Guiet C, Brière F, Vlach J, Lebecque S, Trinchieri G, Bates EE. Human TLR10 is a functional receptor, expressed by B cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cells, which activates gene transcription through MyD88. J Immunol. 2005;174:2942–2950. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi F, Smith KD, Ozinsky A, et al. The innate immune responseto bacterial flagellin is mediated by Toll-like receptor 5. Nature. 2001;410:1099–1103. doi: 10.1038/35074106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil F, Hemmi H, Hochrein H, et al. Species-specific recognition of single-stranded RNA via Toll-like receptor 7 and 8. Science. 2004;303:1526–1529. doi: 10.1126/science.1093620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmi H, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, et al. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature. 2000;408:740–745. doi: 10.1038/35047123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertz CJ, Wu Q, Porter EM, Zhang YJ, Weismüller KH, Godowski PJ, Ganz T, Randell SH, Modlin RL. Activation of Toll-like receptor 2 on human tracheobronchial epithelial cells induces the antimicrobial peptide human beta defensin-2. J Immunol. 2003;171:6820–6826. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.12.6820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homma T, Kato A, Hashimoto N, Batchelor J, Yoshikawa M, Imai S, Wakiguchi H, Saito H, Matsumoto K. Corticosteroid and cytokines synergistically enhance toll-like receptor 2 expression in respiratory epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;31:463–469. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0161OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung V, Rothenfusser S, Britsch S, Krug A, Jahrsdörfer B, Giese T, Endres S, Hartmann G. Quantitative expression of toll-like receptor 1–10 mRNA in cellular subsets of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and sensitivity to CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. J Immunol. 2002;168:4531–4537. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hozono Y, Ueta M, Hamuro J, et al. Human corneal epithelial cells responds to ocular-pathogenic, but not to nonpathogenic-flagellin. Biochem Biophys Res Communs. 2006;347:238–247. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.06.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang LC, Petkova TD, Reins RY, Proske RJ, McDermott AM. Multifunctional roles of human cathelicidin (LL-37) at the ocular surface. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:2369–2380. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang LC, Reins RY, Gallo RL, McDermott AM. Cathelicidin-deficient (Cnlp −/−) mice show increased susceptibility to Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007a;48:4498–4508. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang LC, Redfern RL, Narayanan S, Reins RY, McDermott AM. In vitro activity of human beta-defensin 2 against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the presence of tear fluid. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007b;51:3853–3860. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01317-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janeway CA, Jr, Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeng BH. Preserving the cornea: corneal storage media. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2006;17:332–337. doi: 10.1097/01.icu.0000233950.63853.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Qin Q, Chen W, et al. Expression of Toll-like receptors in healthy and herpes simplex virus-infected cornea. Cornea. 2007;26:847–852. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318093de1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Qin Q, Lin Z, Chen W, Qu J. Expression of toll-like receptors in the Fusarium solani infected cornea. Curr Eye Res. 2008;33:319–324. doi: 10.1080/02713680802008238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Qin Q, Tu L, Qu J. Glucocorticoids inhibit the innate immune system of human corneal fibroblast through their suppression of toll-like receptors. Mol Vis. 2009;15:2435–2441. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai K, Shimura H, Minagawa M, Ito A, Tomiyama K, Ito M. Expression of functional Toll-like receptor 2 on human epidermal keratinocytes. J Dermatol Sci. 2002;30:185–194. doi: 10.1016/s0923-1811(02)00105-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai N, Fukuda K, Fujitsu Y, Lu Y, Chikamoto N, Nishida T. Lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and chemokines in cultured human corneal fibroblasts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:114–120. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Zhang J, Yu FS. Toll-like receptor 2-mediated expression of beta-defensin-2 in human corneal epithelial cells. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:380–389. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Yin J, Zhang J, Yu FS. Modulation of corneal epithelial innate immune response to pseudomonas infection by flagellin pretreatment. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:4664–4670. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Hazlett LD, Yu FS. Flagellin suppresses the inflammatory response and enhances bacterial clearance in a murine model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis. Infect Immun. 2008;76:89–96. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01232-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Shen J, Beuerman RW. Expression of toll-like receptors in human limbal and conjunctival epithelial cells. Mol Vis. 2007;13:813–822. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Raghunath M, Tan D, et al. Defensins HNP1 and HBD2 stimulation of wound-associated responses in human conjunctival fibroblasts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:3811–3819. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Zhu HY, Beuerman RW. Stimulation of specific cytokines in human conjunctival epithelial cells by defensins HNP1, HBD2, and HBD3. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:644–653. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Kumar A, Gui JF, Yu FS. Staphylococcus aureus lipoproteins trigger human corneal epithelial innate response through toll-like receptor-2. Microb Pathog. 2008;44:426–434. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maltseva IA, Fleiszig SM, Evans DJ, Kerr S, Sidhu SS, McNamara NA, Basbaum C. Exposure of human corneal epithelial cells to contact lenses in vitro suppresses the upregulation of human beta-defensin-2 in response to antigens of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Exp Eye Res. 2007;85:142–153. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer WJ, Irschick UM, Moser P, Wurm M, Huemer HP, Romani N, Irschick EU. Characterization of antigen-presenting cells in fresh and cultured human corneas using novel dendritic cell markers. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:4459–4467. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott AM, Redfern RL, Zhang B, Pei Y, Huang L, Proske RJ. Defensin Expression by the Cornea: Multiple Signalling Pathways Mediate IL- 1beta Stimulation of hBD-2 Expression by Human Corneal Epithelial Cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:1859–1865. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott AM, Redfern RL, Zhang B. Human beta-defensin 2 is upregulated during re-epithelialization of the cornea. Curr Eye Res. 2001;22:64–67. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.22.1.64.6978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara NA, Van R, Tuchin OS, Fleiszig SM. Ocular surface epithelia express mRNA for human beta defensin-2. Exp Eye Res. 1999;69:483–490. doi: 10.1006/exer.1999.0722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M, Lopez-Garcia B, Braff M, Dorschner RA, Gallo RL. Postsecretory processing generates multiple cathelicidins for enhanced topical antimicrobial defense. J Immunol. 2004;172:3070–3077. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.3070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CJ, Foster BA, Mannis MJ, Selsted ME, Reid TW. Defensins are mitogenic for epithelial cells and fibroblasts. J. Cell. Physiol. 1993;155:408–413. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041550223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan S, Miller WL, McDermott AM. Expression of human betadefensins in conjunctival epithelium: relevance to dry eye disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:3795–3801. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niyonsaba F, Someya A, Hirata M, et al. Evaluation of the effects of peptide antibiotics human beta-defensins-1/-2 and LL-37 on histamine release and prostaglandin D(2) production from mast cells. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1066–1075. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200104)31:4<1066::aid-immu1066>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei Y, Reins RY, McDermott AM. Aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) 3A1 expression by the human keratocyte and its repair phenotypes. Exp Eye Res. 2006;83:1063–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfern RL, McDermott AM. Toll-like receptors in ocular surface disease. Exp Eye Res. 2010;90:679–687. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Santiago B, Hernandez-Pando R, Carranza C, Juarez E, Contreras JL, Aguilar-Leon D, Torres M, Sada E. Expression of cathelicidin LL-37 during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in human alveolar macrophages, monocytes, neutrophils, and epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2008;76:935–941. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01218-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowlett RM, Chrestensen CA, Nyce M, et al. MNK kinases regulate multiple TLR pathways and innate proinflammatory cytokines in macrophages. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G452–G459. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00077.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sack RA, Nunes I, Beaton A, et al. Host-defense mechanism of the ocular surfaces. Biosci Rep. 2001;21:463–480. doi: 10.1023/a:1017943826684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott MG, Davidson DJ, Gold MR, et al. q. The human antimicrobial peptide LL-37 is a multifunctional modulator of innate immune responses. J Immunol. 2002;169:3883–3891. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starner TD, Agerberth B, Gudmundsson GH, McCray PB., Jr Expression and activity of beta-defensins and LL-37 in the developing human lung. J Immunol. 2005;174:1608–1615. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabeta K, Georgel P, Janssen E, et al. Toll-like receptors 9 and 3 as essential components of innate immune defense against mouse cytomegalovirus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3516–3521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400525101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi O, Sato S, Horiuchi T, et al. Cutting edge: role of Toll-like receptor 1 in mediating immune response to microbial lipoproteins. J Immunol. 2002;169:10–14. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Territo MC, Ganz T, Selsted ME, Lehrer R. Monocyte-chemotactic activity of defensins from human neutrophils. J. Clin. Investig. 1989;84:2017–2020. doi: 10.1172/JCI114394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsan MF, Gao B. Endogenous ligands of Toll-like receptors. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:514–519. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0304127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong L, Diebold Y, Calonge M, Gao J, Stern ME, Beuerman RW. Comparison of gene expression profiles of conjunctival cell lines with primary cultured conjunctival epithelial cells and human conjunctival tissue. Gene Expr. 2009;14:265–278. doi: 10.3727/105221609788681231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueta M, Nochi T, Jang MH, et al. Intracellularly expressed TLR2s and TLR4s contribution to an immunosilent environment at the ocular mucosal epithelium. J Immunol. 2004;173:3337–3347. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueta M, Hamuro J, Kiyono H, Kinoshita S. Triggering of TLR3 by polyI:C in human corneal epithelial cells to induce inflammatory cytokines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;331:285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.02.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wetering S, Mannesse-Lazeroms SP, Van Sterkenburg MA, Daha MR, Dijkman JH, Hiemstra PS. Effect of defensins on interleukin-8 synthesis in airway epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;272:L888–L896. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.5.L888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vora P, Youdim A, Thomas LS, Fukata M, Tesfay SY, Lukasek K, Michelsen KS, Wada A, Hirayama T, Arditi M, Abreu MT. Beta-defensin-2 expression is regulated by TLR signaling in intestinal epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:5398–5405. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M, McClellan SA, Barrett RP, Hazlett LD. Beta-defensin-2 promotes resistance against infection with P. aeruginosa. J Immunol. 2009a;182:1609–1601. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M, McClellan SA, Barrett RP, Zhang Y, Hazlett LD. Beta-defensins 2 and 3 together promote resistance to Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis. J Immunol. 2009b;183:8054–8060. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Gao J, Ren M. Expression profiles and function of Toll-like receptors in human corneal epithelia. Chin Med J. 2007;120:893–897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang IA, Fong KM, Holgate ST, Holloway JW. The role of Toll-like receptors and related receptors of the innate immune system in asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;6:23–28. doi: 10.1097/01.all.0000200503.77295.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D, Chertov O, Bykovskaia SN, Chen Q, Buffo MJ, Shogan J, Anderson M, Schroder JM, Wang JM, Howard OM, Oppenheim JJ. Beta-defensins: linking innate and adaptive immunity through dendritic and T cell CCR6. Science. 1999;286:525–528. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zasloff M. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature. 2002;415:389–395. doi: 10.1038/415389a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Wu XY. Aspergillus fumigatus antigens activate immortalized human corneal epithelial cells via toll-like receptors 2 and 4. Curr Eye Res. 2008;33:447–454. doi: 10.1080/02713680802130339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]