Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) continues to be the most common cause of cognitive and motor alterations in the aging population. Accumulation of amyloid β (Aβ)-protein oligomers and the microtubule associated protein-TAU might be responsible for the neurological damage. We have previously shown that Cerebrolysin (CBL) reduces the synaptic and behavioral deficits in amyloid precursor protein (APP) transgenic (tg) mice by decreasing APP phosphorylation via modulation of glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK3β) and cyclin-dependent kinase-5 (CDK5) activity. These kinases also regulate TAU phosphorylation and are involved in promoting neurofibrillary pathology. In order to investigate the neuroprotective effects of CBL on TAU pathology, a new model for neurofibrillary alterations was developed using somatic gene transfer with adeno-associated virus (AAV2)-mutant (mut) TAU (P301L). The Thy1-APP tg mice (3 m/o) received bilateral injections of AAV2-mutTAU or AAV2-GFP, into the hippocampus. After 3 months, compared to non-tg controls, in APP tg mice intra-hippocampal injections with AAV2-mutTAU resulted in localized increased accumulation of phosphorylated TAU and neurodegeneration. Compared with vehicle controls, treatment with CBL in APP tg injected with AAV2-mutTAU resulted in a significant decrease in the levels of TAU phosphorylation at critical sites dependent on GSK3β and CDK5 activity. This was accompanied by amelioration of the neurodegenerative alterations in the hippocampus. This study supports the concept that the neuroprotective effects of CBL may involve the reduction of TAU phosphorylation by regulating kinase activity.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s, Amyloid precursor protein, Phosphorylation, Kinase, Hippocampus, Viral vector

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common neurodegenerative disorder in Europe and the US and is characterized by cognitive deficits, neurodegeneration, amyloid plaque deposition, neurofibrillary tangles and gliosis [73, 81]. The neurofibrillary pathology is characterized by the intracellular accumulation of aggregated and hyperphosphorylated forms of the cytoskeletal associated protein-TAU [10, 34, 82]. The neurodegenerative process in the initial stages of AD targets the synaptic terminals [11, 41] and then propagates to axons and dendrites leading to neuronal dysfunction and eventually to neuronal death in later stages of the disease [24]. Although the precise mechanisms leading to neurodegeneration in AD are not completely understood, recent studies suggest that alterations in the processing of amyloid precursor protein (APP), resulting in the accumulation of amyloid-β protein (Aβ) and APP C-terminal products, might play a key role in the pathogenesis of AD [28, 30, 76]. Oligomeric aggregates of Aβ might lead to synaptic damage [74] by disrupting synaptic vesicle release, axoplasmic flow and cytoskeletal function associated with alterations in TAU. This synaptic pathology in the hippocampus results in memory and learning deficits characteristic of AD [85]. Although some therapies are currently under investigation for the Aβ and TAU pathology in AD, most compounds currently available are limited to targeting levels of cholinergic neurotransmission [77].

The nootrophic agent Cerebrolysin™ (CBL, a mixture of about 25% low molecular weight biologically active peptides and free amino acids obtained by biotechnological methods using enzymatic breakdown of purified porcine brain proteins) has been shown to improve memory in patients with mild to moderate cognitive impairment [1, 68, 69, 87] and to display neurotrophic activity in vitro [38] and in animal models of neurodegeneration [15, 42, 84]. Moreover, CBL has been shown to ameliorate the neurodegenerative alterations and amyloid burden in an APP model of AD-like pathology [61]. We have recently shown that CBL might reduce the amyloid pathology by decreasing APP production and proteolysis [64] by regulating signaling pathways that mediate the phosphorylation of APP namely, glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK3β) and cyclin-dependent kinase-5 (CDK5) activity [61, 63, 65].

Therefore, CBL has significant effects in several key aspects related to AD pathogenesis; however, the effects of CBL in relation to neurofibrillary pathology and the interactions between APP products and TAU remain unclear. Recent studies have shown that reducing TAU levels by deleting the TAU gene [58, 80] or by immunotherapy [3, 50, 51, 75] may be protective in APP tg models. Though in vitro studies have suggested that CBL treatment reduces TAU phosphorylation [58, 80], it remains unclear whether CBL might reduce neurofibrillary pathology in vivo. Remarkably, the signaling pathways activated during Aβ production and abnormal TAU phosphorylation are analogous and include GSK3β and CDK5 [70]. In this context, we propose that as CBL regulates these kinase pathways then it may also in turn reduce neurofibrillary pathology. For this study, we developed a new model of AD-neurofibrillary pathology wherein APP tg mice received intra-hippocampal injections of an adeno-associated virus (AAV2) expressing mutant (mut) (P301L) TAU. In this model, treatment with CBL for 3 months significantly reduced TAU phosphorylation, neurofibrillary pathology and neuronal loss in the hippocampus of APP tg mice.

Materials and methods

Production and testing of AAV2-TAU constructs

We chose the AAV2 to express mutant TAU as previous studies have shown that this viral vector drives high levels of transgene expression in neuronal populations in various regions of the CNS [44, 53] and is effective at over expressing TAU [29]. Moreover, the P301L mutant of TAU which is associated with familial forms of fronto-temporal dementia [35, 56] has been shown to promote neurofibrillary pathology when co-expressed in APP tg mice [19]. Our P301L construct is based on the 412aa isoform that contains one N-terminal domain (from Exon 2) and four microtubule-binding domains (from Exons 9, 10, 11 and 12). For the preparation of the AAV2-mutTAU, the human TAU cDNA was PCR cloned from the PCDAN3.1-hTAU P301L T+24R construct (donated by Brian Kraemer, Univ. Washington) and inserted into pCRII vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The cDNA sequence was verified then further cloned into the pAAV2-MCS vector from the AAV2 Helper-Free system (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The final plasmid was submitted to ViraPure (San Diego, CA) for packaging and preparation. Control experiments were performed with an AAV2-GFP construct from ViraPure. The constructs were validated in vitro by infecting a rat neuronal cell line (B103) and the human neuronal cell line (SH-SY) with AAV2-mutTAU or GFP. In some cases an empty AAV2 construct was used as control.

Intrahippocampal injections with AAV2-mutTAU, generation of APP Tg Mice, and CBL treatment

This study had two main objectives, the first being to examine the effects of AAV2-mut TAU injection and the second to assess the effects of CBL treatment in APP tg mice infected with AAV2-mutTAU, to this end two sets of experiments were performed.

In the first set of experiments, a total of 16 mice (non-tg mice n = 8 and APP tg mice n = 8, 3-month old) received bilateral intra-hippocampal injections with AAV2-mutTAU or AAV2-GFP. The APP tg mice express mutated (Swedish K670M/N671L, London V717I) human (h)APP751 under the control of the mThy-1 promoter (mThy1-hAPP751) (line 41) [60]. We have previously shown that these mice display loss of synaptic contacts, defects in neurogenesis, high levels of Aβ 1–42 production, early amyloid deposition and behavioral deficits [62, 64, 66]. Genomic DNA was extracted from tail biopsies and analyzed by PCR amplification, as described previously [59]. Transgenic lines were maintained by crossing heterozygous tg mice with non-transgenic (non-tg) C57BL/6 × DBA/2 F1 breeders. All mice were heterozygous with respect to the transgene. For the AAV2 injections, mice were deeply anesthetized and placed in the stereotaxic frame. Two microliters of each AAV2 (TAU or GFP) (~8 × 1012 vg/ml were injected with a 10 µl Hamilton syringe for 3 min at a rate of 0.25 µl/min a Nano-injector system. The needle was allowed to remain in the brain for an additional 2 min. Coordinates for stereotaxic injections were determined according to the Paxinos Atlas of the mouse brain [52]. Mice were sacrificed 1 month following the injections and analyzed biochemically for levels TAU phosphorylation and neurodegeneration.

For the second set of experiments, aimed at assessing the effects of CBL treatment in APP tg mice injected with AAV2-mutTAU, a total of 32 (3-month old; 8 mice per group) APP tg mice were utilized. Mice received bilateral intra-hippocampal injections with AAV2-mutTAU or AAV2-GFP as described above. One month after the injections mice were started with daily intra-peritoneal injections of CBL (2.5 ml/kg) or vehicle alone for 3 month. APP tg mice were divided into four groups as follows: (1) APP tg, injected with AAV2-mutTAU treated with CBL; (2) APP tg, injected with AAV2-mutTAU treated with saline vehicle; (3) APP tg, injected with AAV2-GFP treated with CBL and (4) APP tg, injected with AAV2-GFP treated with saline vehicle. Additional control experiments were performed with an empty AAV2 construct.

At the end of this period mice were sacrificed for analysis of TAU phosphorylation and neurodegeneration assessment. All experiments described were approved by the animal subjects committee at the University of California at San Diego (UCSD) and were performed according to NIH guidelines for animal use.

Tissue processing

In accordance with NIH guidelines for the humane treatment of animals, mice were anesthetized with chloral hydrate and flush-perfused transcardially with 0.9% saline. Brains were removed and divided sagitally. The left hemibrain was post-fixed in phosphate-buffered 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4) at 4°C for 48 h and sectioned at 40 µm with a Vibratome 2000 (Leica, Germany), while the right hemibrain was snap frozen and stored at −70°C for protein analysis.

Western blot analysis

From each case, the hippocampus was dissected, homogenized and divided by ultracentrifugation into cytosolic and membrane (particulate) fractions [67]. For western blot analysis, 15 µg per lane of cytosolic and particulate fractions, assayed by the Lowry method, were loaded into 10% SDS-PAGE gels and blotted onto nitrocellulose paper. Briefly, as previously described [21], blots were incubated with antibodies against phosphorylated tau including PHF-1 (Phosphoserine 396/404 IgG1), CP9 (mouse monoclonal, phosphothreonine 231 IgG2b), CP13 (Phosphoserine 202 IgG1), AT8 (Phosphoserine 202 and phosphothreonine 205 IgG1) (mouse monoclonal, 1:1,000, Innogenetics, Alpharetta, GA). The phospho TAU antibodies and the MC1 antibody (mouse monoclonal, epitope aa 312–322, IgG1) were a kind gift from Dr. Peter Davies and have been previously characterized [27, 86]. Total TAU (tTAU) was also analyzed (Rabbit polyclonal, 1:1,000, Dako, Carpinteria, CA). Blots were also incubated with antibodies against SAPK1 (pSAPK1, 1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), CDK5 (pCDK5, rabbit polyclonal, 1:1,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and GSK3β (pGSK3β, mouse monoclonal, 1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology). While the antibodies against pSAPK1 (phosphorylated at amino acid residues threonine 183 and tyrosine 185) and pCDK5 (phosphorylated at amino acid residues serine 159) (1:1,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) recognize the activated forms of these enzymes, the one against pGSK3β (phosphorylated at amino acid residue serine 9) identifies the inactivated kinase. Additional immunoblot analysis was performed with antibodies against total SAPK1 (tSAPK1, rabbit polyclonal, 1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology), total CDK5 (tCDK5, rabbit polyclonal, 1:1,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and total GSK3β (tGSK3β, mouse monoclonal, 1:1,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). After overnight incubation with primary antibodies, membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies tagged with horseradish peroxidase (HRP, 1:5,000, SantaCruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence and analyzed with a Versadoc XL imaging apparatus (BioRad, Hercules, CA). Analysis of actin levels was used as loading control.

Analysis of neurodegeneration, Aβ deposits and TAU immunoreactivity

To evaluate neurodegeneration and phosphorylation of TAU, blind-coded 40 µm thick vibratome sections were immunolabeled with the mouse monoclonal antibody against microtubule associated protein-2 (MAP2; dendritic marker, 1:200, Chemicon, Temecula, CA) as previously described [62, 65]. After overnight incubation with the primary antibodies, sections were incubated with FITC-conjugated horse anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (1:75, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), transferred to SuperFrost slides (Fisher Scientific, Tustin, CA) and mounted under glass coverslips with anti-fading media (Vector). All sections were processed under the same standardized conditions. The immunolabeled blind-coded sections were imaged with the laser-scanning confocal microscope (LSCM, MRC1024, BioRad, Hercules, CA) and analyzed with the Image 1.43 program (NIH), as previously described [62] to determine the percent area of the neuropil covered by MAP2 immunoreactive terminals.

To determine neuronal density an additional set of sections were immunolabeled as previously described with an antibody against NeuN (general neuronal marker, 1:1,000, Chemicon) and reacted with diamino-benzidine (DAB). Sections were analyzed with the Stereo-Investigator Software (MBF Biosciences), images collected according to the optical disector method were analyzed as previously described [6, 7]. Three immunolabeled sections were analyzed per mouse and the average of individual measurements was used to calculate group means.

Aβ deposits were detected as previously described, briefly vibratome sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with the mouse monoclonal antibody 4G8 (1:600, Senetek, Napa, CA), followed by incubation with a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Vector Laboratories). Sections were imaged with the LSCM (MRC1024, BioRad) as described previously [47] and digital images were analyzed with the NIH Image 1.43 program to determine the percent area occupied by Aβ deposits. Three immunolabeled sections were analyzed per mouse and the average of individual measurements was used to calculate group means.

For analysis of TAU immunoreactivity, sections were immunolabeled as previously described [67] with the antibodies against pTAU (PHF1, Peter Davis) and tTAU (Dako) and reacted with DAB. From each case, 3 serial blind-coded sections were scanned with a digital bright field photo-microscope (Olympus). From each Sect. 4 images of the hippocampus were obtained and analyzed for levels of immunoreactivity with the ImageQuant program. Results were averaged and expressed as mean per case.

To evaluate the cellular distribution of pTAU, double immunocytochemical analysis was performed as previously described [43]. For this purpose, vibratome sections were immunolabeled with a monoclonal antibody against pTAU (PHF1, 1:10,000) detected with the Tyramide Signal Amplification™-Direct (Red) system (1:100, NEN Life Sciences, Boston, MA) and the mouse monoclonal antibody against MAP2 (1:500) detected with FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:75, Vector Laboratories) [43]. All sections were processed simultaneously under the same conditions and experiments were performed twice to assess reproducibility. Sections were imaged with a Zeiss 63X (N.A. 1.4) objective on an Axiovert 35 microscope (Zeiss, Germany) with an attached MRC1024 LSCM system (BioRad) [43]. To confirm the specificity of primary antibodies, control experiments were performed where sections were incubated overnight in the absence of primary antibody (deleted) or preimmune serum and primary antibody alone.

Transmitted electron microscopy and immunogold analysis

Vibratome sections were pre-embedded with 50% Durcupan epoxy resin, and 50% ethanol (dry) for 30 min and then embedded in Durcupan mix epoxy resin and polymerization at vacuum at 60°C for 48 h. After the resin was polymerized, the hippocampus was isolated and mounted into plastic cylinders, sectioned with an ultra microtome (Reichert Ultracut E) at 60 nm thickness and collected in nickel grids for immunogold labeling. The grids were treated with antigen retrieval (sodium periodate saturated in water) for 1 min washed in distilled (di) water, blocked with 3% BSA in TBS for 30 min and then incubated with the PHF1 antibody (1:100) overnight. Next day, the grids were washed in TBS, blocked with 3% BSA, and incubated with the secondary antibody IgG-antimouse/10 nm gold particles (AURION Immunogold reagents) for 2 h at room temp. The sections were then washed in TBS and di-water, and the labeling enhanced using Silver mixture (AURION R-gent SE-EM) for 25 min then washed extensively with di-water. The immunostained grids were post stained using saturated Uranyl Acetate sol. in 50% Ethanol, for 20 min at room temperature, washed in di-water, and placed in bismuth nitrate solution for 10 min followed by a final wash in di-water. The immunolabeled grids were analyzed with a Zeiss EM10 electron microscope and electron micrographs obtained at a magnification of 5,000 and 35,000.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were carried out with the StatView 5.0 program (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Differences among means were assessed by one-way ANOVA with post hoc Dunnett’s. Comparisons between two groups were assessed using the two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. Correlation studies were carried out by simple regression analysis and the null hypothesis was rejected at the 0.05 level.

Results

In vitro characterization of TAU expression levels in neuronal cell cultures

The B103 and SH-SY neuronal cell lines were used to confirm the ability of the viral vector to drive TAU expression. These lines are derived from rat and human neuronal tumors, respectively, and share many typical neuronal properties with other commonly used neuronal cell lines, including outgrowth of neurites upon differentiation, synthesis of neurotransmitters, possession of neurotransmitter receptors and electrical excitability of surface membranes [71]. Immunocytochemical analysis with antibodies against p-TAU (PHF1) showed high levels of expression in the neuronal cell lines compared to controls (Fig. S1a, b). Over 85% of the cells infected with the AAV2-mutTAU were immunostained with the PHF-1 antibody (Fig. S1b). Similarly, infection of the neuronal cell lines with AAV2-GFP at an MOI of 30 resulted in GFP expression in about 90% of plated cells in comparison to control cells (Fig. S1c, d). Immunoblot analysis of cell lysates from B103 cells, revealed pTAU immunoreactive bands at an estimated molecular weight of 50–60 kDa in cells infected with AAV2-mutTAU (Fig. S1e).

TAU phosphorylation in APP tg and non-tg mice injected with AAV2-mutTAU

To further verify the in vivo ability of the AAV2 viral vector to over express TAU non-tg and APP tg mice received intra-hippocampal injections with AAV2-mutTAU or AAV2-GFP. Mice were sacrificed 1 month later and analyzed immunohistochemically for the presence of pTAU.

Analysis revealed that non-tg mice injected with AAV2-mutTAU displayed moderate levels of pTAU (PHF1) in the neuronal cells bodies (Fig. 1b, f), in comparison to the AAV2-GFP- injected non-tg mice (Fig. 1a, e). Confocal analysis of non-tg mice injected with the AAV2-GFP demonstrated abundant expression of the fluorescent protein in the hippocampus (Fig. 1i, m), which was absent in the AAV2-mutTAU-injected non-tg mice (Fig. 1j, n).

Fig. 1.

Patterns of pTAU immunoreactivity in non-tg and APP tg mice injected with AAV2-mutTAU. pTAU immunoreactivity in AAV2-GFP (a, e) and AAV2-mutTAU (b, f) injected hippocampus of non-tg mice. pTAU immunoreactivity in AAV2-GFP (c, g) and AAV2-mut-TAU (d, h) injected hippocampus of APP tg mice. GFP immunoreactivity in AAV2-GFP (i, m) and AAV2-mutTAU (j, n) injected hippocampus of non-tg mice. GFP immunoreactivity in AAV2-GFP (k, o) and AAV2-mutTAU (l, p) injected hippocampus of APP tg mice. Scale bara-d and i-l = 200 µM, e-h and m-p = 50 µM

In contrast, the APP tg mice infected with AAV2-mutTAU showed high levels of pTAU immunoreactivity in the pyramidal cells of the hippocampus (Fig. 1d, h). No significant pTAU immunoreactivity was observed in APP tg mice injected with AAV2-GFP (Fig. 1c, g). Confocal analysis of the sections injected with the AAV2-GFP demonstrated abundant expression of the fluorescent protein in the hippocampus of the APP tg mice (Fig. 1k, o).

Analysis of the time course of pTAU expression in the CA3 region of the hippocampus in APP tg (Fig. S2) revealed a moderate expression at day 14 (Fig. S2c) post injection, becoming much more robust at 30 days following injection (Fig. S2d, analyzed in e).

Double labeling studies in APP tg mice injected with AAV2-mutTAU showed that the pTAU immunoreactivity colocalized with other cytoskeletal proteins such as MAP2 and was re-distributed to the neuronal cell bodies and dendrites (Fig. 2a - f), compared to APP tg mice injected with a control empty AAV2 vector, where mild pTAU immunoreactivity was limited to the cell body (Fig. 2g - i). Ultrastructural analysis of AAV2-mutTAU-injected APP tg mice revealed the presence of fibrillary pathology in the pyramidal neurons composed primarily of straight filaments raging in size between 9 and 11 nm (Fig. 3a, b) and subsequent immunogold studies with the PHF-1 antibody against pTAU demonstrated that these intraneuronal filamentous structures were decorated by gold particles, corroborating the presence of fibrillary pathology (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 2.

pTAU co-localization with cytoskeletal proteins in APP tg mice injected with AAV2-mutTAU. Immunoreactivity for MAP2 (a, d), pTAU (b, e) in APP tg mice injected with AAV2-mutTAU, colocalization (c, f). Immunoreactivity for MAP2 (g), pTAU (h) in APP tg mice injected with AAV2-control vector, colocalization (i). Bar 50 µM

Fig. 3.

Ultrastructural analysis of the cytoskeletal pathology in APP tg mice injected with AAV2-mutTAU. Electron micrographs of filamentous structures (arrows) in the pyramidal neurons of AAV2-mutTAU-injected APP tg mice (a, b magnification ×5,000). Immunogold labeling of filamentous structures in the pyramidal neurons of AAV2-mutTAU-injected APP tg mice (c magnification ×35,000)

Neurodegeneration in APP tg and non-tg mice injected with AAV2-mutTAU

Analysis of neuronal loss in the non-tg injected with AAV2-mutTAU, as evidenced by NeuN immunoreactivity, revealed a modest decrease in the CA3 region of the hippocampus (Fig. 4b, f, arrows) in comparison to non-tg mice injected with AAV2-GFP (Fig. 4a, e). Neuronal loss was more pronounced in the APP tg mice, with mice injected with AAV2-mutTAU (Fig. 4d, h, arrows) demonstrating significantly lower hippocampal NeuN immunoreactivity than those injected with AAV2-GFP (Fig. 4 c, g and analyzed in i).

Fig. 4.

Neurodegeneration in non-tg and APP tg mice injected with AAV2-mutTAU. NeuN immunoreactivity in AAV2-GFP (a, e) and AAV2-mutTAU (b, f) injected hippocampus of non-tg mice. NeuN immunoreactivity in AAV2-GFP (c, g) and AAV2-mutTAU (d, h) injected hippocampus of APP tg mice and analysis of NeuN immunoreactive cells (i). Scale bar a-d and i-l = 200 µM, e-h and m-p = 50 µM. Asterisk indicates significance at p < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA)

Cerebrolysin treatment reduces TAU phosphorylation and neurofibrillary pathology in APP Tg mice injected with AAV2-mutTAU

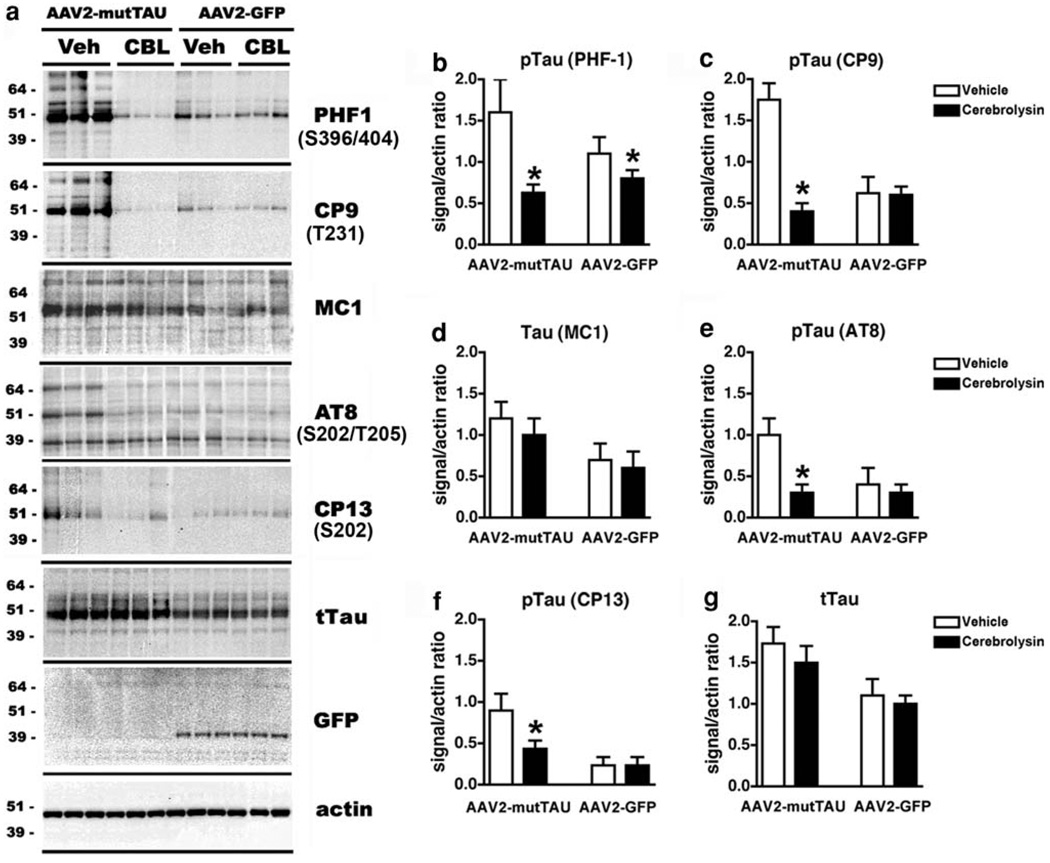

To ascertain the effects of CBL on TAU phosphorylation in APP tg mice injected with AAV2-mutTAU, western blot analysis was performed. As expected levels of pTAU immunoreactivity were highest in homogenates from APP tg mice injected with AAV2-mutTAU compared to AAV2-GFP (Fig. 5a). In the particulate fraction, pTAU immunoreactivity was more readily detected with the PHF1 and CP9 antibodies and to a lesser extent with MC1, AT8 and CP13 antibodies (Fig. 5a). TAU was identified as a complex of 3–4 bands ranging from 50 to 60 kDa. Total TAU (tTAU) was detected in all four groups, both in the insoluble and soluble fractions. Levels of tTAU were higher in mice injected with AAV2-mutTAU compared to AAV2-GFP (Fig. 5a). A band at 39 kDa corresponding to GFP was only detected in mice injected with AAV2-GFP (Fig. 5a).

Fig. 5.

Immunoblot analysis of TAU levels in APP tg mice injected with AAV2-mutTAU and treated with CBL. Immunoblot analysis of TAU with antibodies against PHF-1, CP9, MC1, AT8, CP13, tTAU and GFP (a) in AAV2-mutTAU and AAV2-GFP injected vehicle- or CBL-treated APP tg mice. Quantitative analyses of immunoblot (b-g). Asterisk indicates significance at p < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA)

Compared to mice treated with vehicle alone, in the CBL-treated APP tg mice injected with AAV2-mutTAU, there was a significant reduction in the levels of pTAU at the epitopes detected by the PHF1, CP9, AT8 and CP13 antibodies in the particulate fraction (Fig. 5a-c, e, f). However, levels of TAU phosphorylation at the epitopes detected by the MC1 antibody or in the levels of tTAU in the particulate fraction were unaffected by CBL treatment (Fig. 5a, d, g). In APP tg mice injected with AAV2-GFP, the endogenous levels of pTAU and tTAU in the particulate fraction were comparable between the vehicle and CBL-treated groups (Fig. 5a, g).

Consistent with the results from the immunoblots, the immunocytochemical analysis showed that compared to the vehicle-treated AAV2-mutTAU-injected APP tg mice (Fig. 6a), in CBL-treated APP tg mice injected with AAV2-mutTAU (Fig. 6b) there was a significant reduction in the levels of pTAU as detected by the PHF1 antibody (Fig. 6e). CBL treatment had no effects on the levels of GFP expression (Fig. 6e - i).

Fig. 6.

Effects of CBL on neuronal pTAU immunoreactivity in APP tg mice injected with AAV2-mutTAU and treated with CBL. pTAU immunoreactivity in AAV2-mutTAU-injected vehicle-treated (a) and CBL-treated (b) APP tg mice. GFP immunoreactivity in AAV2-mut-TAU-injected vehicle-treated (f) and CBL-treated (g) APP tg mice. pTAU immunoreactivity in AAV2-GFP injected vehicle-treated (c) and CBL-treated (d) APP tg mice. GFP immunoreactivity in AAV2-GFP injected vehicle-treated (h) and CBL-treated (i) APP tg mice. Quantitative analyses of pTAU immunoreactivity in AAV2-mutTAU and AAV2-GFP injected vehicle- or CBL-treated mice (e). Scale bar 50 µM. Asterisk indicates significance at p < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA)

Analysis of the percentage of the neuropil covered by Aβ immunoreactivity (Fig. S3a-d and analyzed in e) revealed a similar deposition in the APP tg mice injected with AAV2-TAU (2.48% ± 0.301) and those injected with AAV2-GFP (1.8% ± 0.311). In agreement with previous studies [60], CBL treatment reduced at comparable levels the accumulation of amyloid deposits in APP tg AAV2-TAU injected mice (1.58% ± 0.192, a significant reduction of 63.7%, one-way ANOVA, p < 0.05) and APP tg AAV2-GFP injected mice (0.75% ± 0.384, a significant reduction of reduction of 41.7%, one-way ANOVA, p < 0.05).

Neuroprotective effects of Cerebrolysin on neurodegenerative pathology in APP Tg mice injected with AAV2-mutTAU

Analysis of neuronal loss, as evidenced by NeuN immunoreactivity, and dendritic complexity, as evidenced by MAP2 immunoreactivity, revealed that vehicle-treated APP tg mice injected with AAV2-mutTAU displayed a more widespread pyramidal neurons loss (Fig. 7a (arrows), e, i) and reduction in dendritic complexity (Fig. 7j, n, r) in the CA3 region of the hippocampus compared to APP tg mice injected with AAV2-GFP (Fig. 7c, g, l, p). In non-tg mice pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus were of similar characteristics between the AAV2-mut TAU and the AAV2-GFP (not shown).

Fig. 7.

Effects of CBL on neuronal number and dendritic density in APP tg mice injected with AAV2-mutTAU and treated with CBL. NeuN immunoreactivity in the hippocampus of AAV2-mutTAU-injected vehicle-treated (a, e) and CBL-treated (b, f) APP tg mice. NeuN immunoreactivity in the hippocampus of AAV2-GFP injected vehicle-treated (c, g) and CBL-treated (d, h) APP tg mice. Quantitative analysis of NeuN immunoreactivity in AAV2-mutTAU and AAV2-GFP injected vehicle- or CBL-treated APP tg mice (i), dashed line indicates NeuN immunoreactivity in non-tg mice (Fig. 4i). MAP2 immunoreactivity in the hippocampus of AAV2-mutTAU-injected vehicle-treated (j, n) and CBL-treated (k, o) APP tg mice. MAP2 immunoreactivity in the hippocampus of AAV2-GFP injected vehicle-treated (l, p) and CBL-treated (m, q) APP tg mice. Quantitative analysis of MAP2 immunoreactivity in AAV2-mutTAU and AAV2-GFP injected vehicle- or CBL-treated APP tg mice (r). Scale bar a-d and j-m = 200 µM, e-h and n-q = 50 µM. Asterisk indicates significance at p < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA)

Cerebrolysin treatment reduced the neurodegenerative pathology observed in the APP tg mice. Compared to mice treated with vehicle alone (Fig. 7a, e, i, j, n), the CBL-treated APP tg mice injected with AAV2-mutTAU displayed a significant recovery of neuronal density [Fig. 7b, f, i (dashed line indicates NeuN immunoreactivity in non-tg mice, Fig. 4i)] and dendritic complexity (Fig. 7k, o, r) in the hippocampus. CBL treatment also ameliorated the moderate neuronal (Fig. 7d, h, i) and dendritic alterations (Fig. 7m, q, r) in APP tg mice injected with AAV2-GFP.

Effects of Cerebrolysin on GSK3β and CDK5 in APP Tg mice injected with AAV2-mutTAU

We have previously shown that CBL is capable of modulating Aβ production by regulating the activities of GSK3β and CDK5 [65]. Both of these kinases are also known to phosphorylate TAU at critical residues important in neurofibrillary tangle formation [8, 9, 14, 36, 37, 39, 40, 45, 79]. For this reason, we analyzed by immunoblot the levels of phosphorylation of kinases involved in TAU phosphorylation. This study showed that in APP tg mice, injected with either AAV2-mutTAU or GFP, CBL treatment reduced the levels of pCDK5 (Ser 159, active form) (Fig. 8a, b) and increased the levels of pGSK3β (Ser9, inactive form) (Fig. 8a, c), while the levels of pERK were unchanged (Fig. 8a, d). These results support the notion that the neuroprotective effects of CBL might depend in its ability to regulate CDK5 and GSK3β dependent TAU phosphorylation sites.

Fig. 8.

Immunoblot analysis of CBL effects on pGSK3β and pCDK5 levels in APP tg mice injected with AAV2-mutTAU treated with CBL. Immunoblot analysis of AAV2-mutTAU and AAV2-GFP injected vehicle- or CBL-treated APP tg mice with antibodies against tCDK5, pCDK5, tGSK3β, pGSK3β, tERK and pERK (a). Quantitative ratio analysis of pCDK5/tCDK5 (b), pGSK3β/tGSK3β (c) and pERK/tERK (d) in AAV2-mutTAU and AAV2-GFP injected vehicle-or CBL-treated APP tg mice. Asterisk indicates significance at p < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA)

Discussion

The present study showed that over expression of mutTAU in the hippocampus of APP tg mice resulted in a greater degree of neurodegeneration in comparison to APP tg mice alone and that CBL treatment reduced the abnormal TAU phosphorylation and neurodegenerative pathology in these mice. Previous studies have modeled the neurofibrillary pathology of AD by either crossing mutTAU tg with APP tg mice [13, 35, 55], co-expressing TAU, APP and PS in a triple tg [49] or by injecting Aβ into the brains of mutTAU tg mice [20]. Over expression of wild type or mutTAU under neuronal promoters only partially reproduces the characteristic fibrillary TAU alterations [2, 4, 13, 16, 18, 20, 23, 33]. However, these effects are enhanced by the addition of APP/Aβ, indicating the importance of interactions between TAU and Aβ in the pathogenesis of AD-like TAU pathology.

To investigate the potential ability of CBL at ameliorating neurofibrillary pathology, we chose to use AAV2-mut-TAU injection into the hippocampus of APP tg mice because with this model it is possible to express TAU at high levels in specific brain regions for long periods of time, without the need for multiple crosses. Remarkably in this model we found, in addition to the increased levels of TAU phosphorylation, more extensive neurodegeneration in the hippocampus compared to APP tg mice alone or non-tg mice injected with AAV2-mutTAU. This, in conjunction with recent studies showing that deletion of TAU is neuroprotective in APP tg mice [58] supports the notion that alterations in TAU might play an important role mediating the mechanisms of neurodegeneration in AD. The neurofibrillary pathology in AD has been extensively investigated both in terms of TAU phosphorylation [31, 32, 39, 40, 83] and truncations [12] because tangle formation plays an important role in the mechanisms of behavioral deficits and neurodegeneration in AD patients [25]. This is of interest because in our combined model, CBL treatment reduced the abnormal TAU phosphorylation and neurodegenerative pathology in the hippocampus.

CBL has previously been shown to improve memory in patients with mild to moderate cognitive impairment [1, 68, 69] and to display neurotrophic activity in animal models of neurodegeneration [15, 42, 84]. Moreover, CBL has been shown to ameliorate the neurodegenerative alterations and amyloid burden in an APP tg model of AD-like pathology [61]. As Aβ is thought to enhance TAU pathology [20], CBL’s effects on the reduction of TAU pathology in the combined model may be related to the effects of CBL at decreasing Aβ production. However, it is worth noting that the effects of CBL on TAU phosphorylation were detected in the particulate fraction of the APP tg mice injected with AAV2-mutTAU while no significant effects were observed in levels of endogenous TAU phosphorylation in the APP tg mice injected with AAV2-GFP.

Therefore, it is likely that the effects of CBL on TAU might involve alternative mechanisms, for example, the effects of CBL on TAU phosphorylation favored specific epitopes including pSer208, pSer 396/404 and pThr231, sites that have been previously shown to be primarily phosphorylated by CDK5 and GSK3β [26, 46, 57, 89]. We have recently shown that CBL might reduce the AD-like pathology in APP tg mice by regulating the activity of signaling pathways that includes these two kinases [61, 63, 65]. Consistent with this possibility, the present study demonstrated that levels of CDK5 phosphorylation associated with CDK5 activation are reduced and levels of phosphor-GSK3β that correspond to inactivation are increased in APP tg mice injected with AAV2-mutTAU mice treated with CBL. This is consistent with recent studies showing that compounds that modulate the CDK5 and GSK3β signaling pathways such as lithium chloride [5, 22, 48, 54, 67, 78] or other inhibitors of GSK3β (sodium tungstate [17] or GSK3β inhibitors investigated in diabetes (CHIR98014) [72]) and CDK5 (such as roscovitine [88]) reduce TAU phosphorylation and the associated neurodegenerative pathology in vivo.

We have previously shown that in APP tg mice CBL reduces Aβ production by modulating APP phosphorylation and maturation and that this involves the regulation of CDK5 and GSK3β [65]; CBL also ameliorates deficits in neurogenesis by enhancing survival of neuronal precursor cells in the hippocampus [66] the present study extends these effects of CBL by demonstrating that it reduces TAU phosphorylation and related neurodegenerative pathology. Taken together, these findings support the possibility that CBL might act at the site of a neurotrophic factor-like receptor that couples with the Akt/GSK3β and CDK5 signaling pathways. The effects of modulating such cascade might exert pleotrophic effects including, neuroprotection, anti-apoptotic, neurogenesis, and anti-amyloid and TAU pathology. The identity of such receptor or sites and more detailed dissection of the signaling pathways involved await further investigation.

In conclusion, this study showed that mutTAU enhances the neurodegenerative pathology in the hippocampus of APP tg mice and indicates that CBL treatment reduces the abnormal TAU phosphorylation and neurodegenerative pathology in the combined AAV2-mutTAU/APP tg mouse model by modulating the activity of CDK5 and GSK3β supporting the possibility that CBL might have beneficial effects in the treatment of the neurofibrillary pathology in AD and other TAUopathies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant AG05131 and by a grant from EBEWE Pharmaceuticals.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00401-009-0505-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Conflict of interest statement Research relating to this manuscript was funded in part by a grant from EBEWE Pharmaceuticals; the manufacturer of CBL, and a portion of the scientific background to CBL and experimental design was provided by employees of EBEWE Pharmaceuticals.

Contributor Information

Kiren Ubhi, Department of Neurosciences, School of Medicine, University of California, La Jolla, San Diego, CA 92093-0624, USA.

Edward Rockenstein, Department of Neurosciences, School of Medicine, University of California, La Jolla, San Diego, CA 92093-0624, USA.

Edith Doppler, EBEWE Pharmaceuticals Research Division, Unterach, Austria.

Michael Mante, Department of Neurosciences, School of Medicine, University of California, La Jolla, San Diego, CA 92093-0624, USA.

Anthony Adame, Department of Neurosciences, School of Medicine, University of California, La Jolla, San Diego, CA 92093-0624, USA.

Christina Patrick, Department of Neurosciences, School of Medicine, University of California, La Jolla, San Diego, CA 92093-0624, USA.

Margarita Trejo, Department of Neurosciences, School of Medicine, University of California, La Jolla, San Diego, CA 92093-0624, USA.

Leslie Crews, Department of Pathology, University of California, La Jolla, San Diego, CA 92093-0624, USA.

Amy Paulino, Department of Neurosciences, School of Medicine, University of California, La Jolla, San Diego, CA 92093-0624, USA.

Herbert Moessler, EBEWE Pharmaceuticals Research Division, Unterach, Austria.

Eliezer Masliah, Email: emasliah@ucsd.edu, Department of Neurosciences, School of Medicine, University of California, La Jolla, San Diego, CA 92093-0624, USA; Department of Pathology, University of California, La Jolla, San Diego, CA 92093-0624, USA.

References

- 1.Alvarez XA, Cacabelos R, Laredo M, Couceiro V, Sampedro C, Varela M, Corzo L, Fernandez-Novoa L, Vargas M, Aleixandre M, Linares C, Granizo E, Muresanu D, Moessler H. A 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of three dosages of Cerebrolysin in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13:43–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andorfer C, Kress Y, Espinoza M, de Silva R, Tucker KL, Barde YA, Duff K, Davies P. Hyperphosphorylation and aggregation of tau in mice expressing normal human tau isoforms. J Neurochem. 2003;86:582–590. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asuni AA, Boutajangout A, Quartermain D, Sigurdsson EM. Immunotherapy targeting pathological tau conformers in a tangle mouse model reduces brain pathology with associated functional improvements. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9115–9129. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2361-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brion JP, Tremp G, Octave JN. Transgenic expression of the shortest human tau affects its compartmentalization and its phosphorylation as in the pretangle stage of Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:255–270. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65272-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caccamo A, Oddo S, Tran LX, LaFerla FM. Lithium reduces tau phosphorylation but not A beta or working memory deficits in a transgenic model with both plaques and tangles. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1669–1675. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chana G, Landau S, Beasley C, Everall IP, Cotter D. Two-dimensional assessment of cytoarchitecture in the anterior cingulate cortex in major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia: evidence for decreased neuronal somal size and increased neuronal density. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:1086–1098. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chana G, Everall IP, Crews L, Langford D, Adame A, Grant I, Cherner M, Lazzaretto D, Heaton R, Ellis R, Masliah E. Cognitive deficits and degeneration of interneurons in HIV+ methamphetamine users. Neurology. 2006;67:1486–1489. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000240066.02404.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho JH, Johnson GV. Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta phosphorylates tau at both primed and unprimed sites. Differential impact on microtubule binding. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:187–193. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206236200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho JH, Johnson GV. Primed phosphorylation of tau at Thr231 by glycogen synthase kinase 3beta (GSK3beta) plays a critical role in regulating tau’s ability to bind and stabilize microtubules. J Neurochem. 2004;88:349–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies P, Ghanbari H, Issacs A, Dickson D, Mattiace L, Rosado M, Vincent I. TG3: a better antibody that Alz-50 for the visualization of Alzheimer-type neuronal pathology. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1993;19:1636. [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeKosky S, Scheff S. Synapse loss in frontal cortex biopsies in Alzheimer’s disease: correlation with cognitive severity. Ann Neurol. 1990;27:457–464. doi: 10.1002/ana.410270502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delobel P, Lavenir I, Fraser G, Ingram E, Holzer M, Ghetti B, Spillantini MG, Crowther RA, Goedert M. Analysis of tau phosphorylation and truncation in a mouse model of human tauopathy. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:123–131. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duff K. Transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease: phenotype and mechanisms of pathogenesis. Biochem Soc Symp. 2001;67:195–202. doi: 10.1042/bss0670195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flaherty DB, Soria JP, Tomasiewicz HG, Wood JG. Phosphorylation of human tau protein by microtubule-associated kinases: GSK3beta and cdk5 are key participants. J Neurosci Res. 2000;62:463–472. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20001101)62:3<463::AID-JNR16>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Francis-Turner L, Valouskova V. Nerve growth factor and nootropic drug Cerebrolysin but not fibroblast growth factor can reduce spatial memory impairment elicited by fimbria-fornix transection: short-term study. Neurosci Lett. 1996;202:1–4. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)12240-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goedert M, Hasegawa M. The tauopathies: toward an experimental animal model. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:1–6. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65242-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomez-Ramos A, Dominguez J, Zafra D, Corominola H, Gomis R, Guinovart JJ, Avila J. Inhibition of GSK3 dependent tau phosphorylation by metals. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2006;3:123–127. doi: 10.2174/156720506776383059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gotz J, Probst A, Spillantini MG, Schafer T, Jakes R, Burki K, Goedert M. Somatodendritic localization and hyperphosphorylation of tau protein in transgenic mice expressing the longest human brain tau isoform. EMBO J. 1995;14:1304–1313. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07116.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gotz J, Chen F, Barmettler R, Nitsch RM. Tau filament formation in transgenic mice expressing P301L tau. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:529–534. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006531200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gotz J, Chen F, van Dorpe J, Nitsch RM. Formation of neurofibrillary tangles in P301l tau transgenic mice induced by Abeta 42 fibrils. Science. 2001;293:1491–1495. doi: 10.1126/science.1062097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hashimoto M, Sagara Y, Everall IP, Mallory M, Everson A, Lang-ford D, Masliah E. Fibroblast growth factor 1 regulates signaling via the GSK3β pathway: implications for neuroprotection. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:32985–32991. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202803200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hong M, Chen DC, Klein PS, Lee VM. Lithium reduces tau phosphorylation by inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:25326–25332. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.25326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hutton M, Lewis J, Dickson D, Yen S, McGowan E. Analysis of tauopathies with transgenic mice. Trends Mol Med. 2001;7:467–470. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(01)02123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hyman B, Gomez-Isla T. Alzheimer’s disease is a laminar regional and neural system specific disease, not a global brain disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1994;15:353–354. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(94)90031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hyman BT, Augustinack JC, Ingelsson M. Transcriptional and conformational changes of the tau molecule in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1739:150–157. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Illenberger S, Zheng-Fischhofer Q, Preuss U, Stamer K, Baumann K, Trinczek B, Biernat J, Godemann R, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E. The endogenous and cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation of tau protein in living cells: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:1495–1512. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.6.1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jicha GA, Bowser R, Kazam IG, Davies P. Alz-50 and MC-1, a new monoclonal antibody raised to paired helical filaments, recognize conformational epitopes on recombinant tau. J Neurosci Res. 1997;48:128–132. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4547(19970415)48:2<128::aid-jnr5>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamenetz F, Tomita T, Hsieh H, Seabrook G, Borchelt D, Iwatsubo T, Sisodia S, Malinow R. APP processing and synaptic function. Neuron. 2003;37:925–937. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klein RL, Dayton RD, Leidenheimer NJ, Jansen K, Golde TE, Zweig RM. Efficient neuronal gene transfer with AAV8 leads to neurotoxic levels of tau or green fluorescent proteins. Mol Ther. 2006;13:517–527. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koo E, Lansbury PJ, Kelly J. Amyloid diseases: abnormal protein aggregation in neurodegeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9989–9990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.9989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee HG, Perry G, Moreira PI, Garrett MR, Liu Q, Zhu X, Takeda A, Nunomura A, Smith MA. Tau phosphorylation in Alzheimer’s disease: pathogen or protector? Trends Mol Med. 2005;11:164–169. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee VM. Regulation of tau phosphorylation in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996;777:107–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb34408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Neurodegenerative tauopathies: human disease and transgenic mouse models. Neuron. 1999;24:507–510. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81106-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee VM, Goedert M, Trojanowski JQ. Neurodegenerative tauopathies. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:1121–1159. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewis J, Dickson DW, Lin WL, Chisholm L, Corral A, Jones G, Yen SH, Sahara N, Skipper L, Yager D, Eckman C, Hardy J, Hutton M, McGowan E. Enhanced neurofibrillary degeneration in transgenic mice expressing mutant tau and APP. Science. 2001;293:1487–1491. doi: 10.1126/science.1058189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li T, Hawkes C, Qureshi HY, Kar S, Paudel HK. Cyclin-dependent protein kinase 5 primes microtubule-associated protein tau site-specifically for glycogen synthase kinase 3beta. Biochemistry. 2006;45:3134–3145. doi: 10.1021/bi051635j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li T, Paudel HK. Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta phosphorylates Alzheimer’s disease-specific Ser396 of microtubule-associated protein tau by a sequential mechanism. Biochemistry. 2006;45:3125–3133. doi: 10.1021/bi051634r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mallory M, Honer W, Hsu L, Johnson R, Masliah E. In vitro synaptotrophic effects of Cerebrolysin in NT2N cells. Acta Neuropathol. 1999;97:437–446. doi: 10.1007/s004010051012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mandelkow EM, Biernat J, Drewes G, Gustke N, Trinczek B, Mandelkow E. Tau domains, phosphorylation, and interactions with microtubules. Neurobiol Aging. 1995;16:355–362. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(95)00025-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mandelkow EM, Schweers O, Drewes G, Biernat J, Gustke N, Trinczek B, Mandelkow E. Structure, microtubule interactions, and phosphorylation of tau protein. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996;777:96–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb34407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Masliah E. Mechanisms of synaptic dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Histol Histopathol. 1995;10:509–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Masliah E, Armasolo F, Veinbergs I, Mallory M, Samuel W. Cerebrolysin ameliorates performance deficits and neuronal damage in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;62:239–245. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(98)00144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Masliah E, Rockenstein E, Veinbergs I, Mallory M, Hashimoto M, Takeda A, Sagara Y, Sisk A, Mucke L. Dopaminergic loss and inclusion body formation in alpha-synuclein mice: implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Science. 2000;287:1265–1269. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5456.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCown TJ. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors in the CNS. Curr Gene Ther. 2005;5:333–338. doi: 10.2174/1566523054064995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mi K, Johnson GV. The role of tau phosphorylation in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2006;3:449–463. doi: 10.2174/156720506779025279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Michel G, Mercken M, Murayama M, Noguchi K, Ishiguro K, Imahori K, Takashima A. Characterization of tau phosphorylation in glycogen synthase kinase-3beta and cyclin dependent kinase-5 activator (p23) transfected cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1380:177–182. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(97)00139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mucke L, Masliah E, Yu GQ, Mallory M, Rockenstein EM, Tat-suno G, Hu K, Kholodenko D, Johnson-Wood K, McConlogue L. High-level neuronal expression of abeta 1–42 in wild-type human amyloid protein precursor transgenic mice: synaptotoxicity without plaque formation. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4050–4058. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04050.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Noble W, Planel E, Zehr C, Olm V, Meyerson J, Suleman F, Gaynor K, Wang L, LaFrancois J, Feinstein B, Burns M, Krishnamurthy P, Wen Y, Bhat R, Lewis J, Dickson D, Duff K. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by lithium correlates with reduced tauopathy and degeneration in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:6990–6995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500466102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oddo S, Caccamo A, Shepherd JD, Murphy MP, Golde TE, Kayed R, Metherate R, Mattson MP, Akbari Y, LaFerla FM. Triple-transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease with plaques and tangles: intracellular Abeta and synaptic dysfunction. Neuron. 2003;39:409–421. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oddo S, Billings L, Kesslak JP, Cribbs DH, LaFerla FM. Abeta immunotherapy leads to clearance of early, but not late, hyperphosphorylated tau aggregates via the proteasome. Neuron. 2004;43:321–332. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oddo S, Vasilevko V, Caccamo A, Kitazawa M, Cribbs DH, LaFerla FM. Reduction of soluble Abeta and tau, but not soluble Abeta alone, ameliorates cognitive decline in transgenic mice with plaques and tangles. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:39413–39423. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608485200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Paxinos G, Franklin K. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. NY: Academic Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peel AL, Klein RL. Adeno-associated virus vectors: activity and applications in the CNS. J Neurosci Methods. 2000;98:95–104. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(00)00183-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perez M, Hernandez F, Lim F, Diaz-Nido J, Avila J. Chronic lithium treatment decreases mutant tau protein aggregation in a transgenic mouse model. J Alzheimers Dis. 2003;5:301–308. doi: 10.3233/jad-2003-5405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perez M, Ribe E, Rubio A, Lim F, Moran MA, Ramos PG, Ferrer I, Isla MT, Avila J. Characterization of a double (amyloid precursor protein-tau) transgenic: tau phosphorylation and aggregation. Neuroscience. 2005;130:339–347. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Poorkaj P, Grossman M, Steinbart E, Payami H, Sadovnick A, Nochlin D, Tabira T, Trojanowski JQ, Borson S, Galasko D, Reich S, Quinn B, Schellenberg G, Bird TD. Frequency of tau gene mutations in familial and sporadic cases of non-Alzheimer dementia. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:383–387. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.3.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reynolds CH, Betts JC, Blackstock WP, Nebreda AR, Anderton BH. Phosphorylation sites on tau identified by nanoelectrospray mass spectrometry: differences in vitro between the mitogen-activated protein kinases ERK2, c-Jun N-terminal kinase and P38, and glycogen synthase kinase-3beta. J Neurochem. 2000;74:1587–1595. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0741587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roberson ED, Scearce-Levie K, Palop JJ, Yan F, Cheng IH, Wu T, Gerstein H, Yu GQ, Mucke L. Reducing endogenous tau ameliorates amyloid beta-induced deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Science. 2007;316:750–754. doi: 10.1126/science.1141736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rockenstein E, McConlogue L, Tan H, Power M, Masliah E, Mucke L. Levels and alternative splicing of amyloid β protein precursor (APP) transcripts in brains of APP transgenic mice and humans with Alzheimer’s disease. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:28257–28267. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.47.28257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rockenstein E, Mallory M, Mante M, Sisk A, Masliah E. Early formation of mature amyloid-b proteins deposits in a mutant APP transgenic model depends on levels of Ab1-42. J Neurosci Res. 2001;66:573–582. doi: 10.1002/jnr.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rockenstein E, Mallory M, Mante M, Alford M, Windisch M, Moessler H, Masliah E. Effects of Cerebrolysin on amyloid-beta deposition in a transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2002;62:327–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rockenstein E, Adame A, Mante M, Moessler H, Windisch M, Masliah E. The neuroprotective effects of Cerebrolysin trade mark in a transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease are associated with improved behavioral performance. J Neural Transm. 2003;110:1313–1327. doi: 10.1007/s00702-003-0025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rockenstein E, Adame A, Mante M, Larrea G, Crews L, Windisch M, Moessler H, Masliah E. Amelioration of the cerebrovascular amyloidosis in a transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease with the neurotrophic compound cerebrolysin. J Neural Transm. 2005;112:269–282. doi: 10.1007/s00702-004-0181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rockenstein E, Torrance M, Mante M, Adame A, Paulino A, Rose JB, Crews L, Moessler H, Masliah E. Cerebrolysin decreases amyloid-beta production by regulating amyloid protein precursor maturation in a transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci Res. 2006;83(7):1252–1261. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rockenstein E, Torrance M, Mante M, Adame A, Paulino A, Rose JB, Crews L, Moessler H, Masliah E. Cerebrolysin decreases amyloid-beta production by regulating amyloid protein precursor maturation in a transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci Res. 2006;83:1252–1261. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rockenstein E, Mante M, Adame A, Crews L, Moessler H, Masliah E. Effects of Cerebrolysin trade mark on neurogenesis in an APP transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;113:265–275. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0166-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rockenstein E, Torrance M, Adame A, Mante M, Bar-on P, Rose JB, Crews L, Masliah E. Neuroprotective effects of regulators of the glycogen synthase kinase-3beta signaling pathway in a transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease are associated with reduced amyloid precursor protein phosphorylation. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1981–1991. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4321-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ruther E, Ritter R, Apecechea M, Freitag S, Windisch M. Efficacy of Cerebrolysin in Alzheimer’s disease. In: Jellinger K, Ladurner G, Windisch M, editors. New trends in the diagnosis and therapy of Alzheimer’s disease. Vienna: Springer; 1994. pp. 131–141. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ruther E, Ritter R, Apecechea M, Freytag S, Windisch M. Efficacy of the peptidergic nootropic drug cerebrolysin in patients with senile dementia of the Alzheimer’s type (SDAT) Pharmacopsychiatry. 1994;27:32–40. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1014271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ryder J, Su Y, Liu F, Li B, Zhou Y, Ni B. Divergent roles of GSK3 and CDK5 in APP processing. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;312:922–929. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schubert D, Heinemann S, Carlisle W, Tarikas H, Kimes B, Patrick J, Steinbach JH, Culp W, Brandt BL. Clonal cell lines from the rat central nervous system. Nature. 1974;249:224–227. doi: 10.1038/249224a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Selenica ML, Jensen HS, Larsen AK, Pedersen ML, Helboe L, Leist M, Lotharius J. Efficacy of small-molecule glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibitors in the postnatal rat model of tau hyperphosphorylation. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;152:959–979. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Selkoe DJ, Schenk D. Alzheimer’s disease: molecular understanding predicts amyloid-based therapeutics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2003;43:545–584. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.43.100901.140248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Selkoe DJ. Soluble oligomers of the amyloid beta-protein impair synaptic plasticity and behavior. Behav Brain Res. 2008;192:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sigurdsson EM. Immunotherapy targeting pathological tau protein in Alzheimer’s disease and related tauopathies. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;15:157–168. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-15202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sinha S, Anderson J, John V, McConlogue L, Basi G, Thorsett E, Schenk D. Recent advances in the understanding of the processing of APP to beta amyloid peptide. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;920:206–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Spencer B, Rockenstein E, Crews L, Marr R, Masliah E. Novel strategies for Alzheimer’s disease treatment. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2007;7:1853–1867. doi: 10.1517/14712598.7.12.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Takahashi M, Yasutake K, Tomizawa K. Lithium inhibits neurite growth and tau protein kinase I/glycogen synthase kinase-3beta-dependent phosphorylation of juvenile tau in cultured hippocampal neurons. J Neurochem. 1999;73:2073–2083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Takashima A. GSK-3 is essential in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9:309–317. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-9s335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tatebayashi Y, Lee MH, Li L, Iqbal K, Grundke-Iqbal I. The dentate gyrus neurogenesis: a therapeutic target for Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2003;105:225–232. doi: 10.1007/s00401-002-0636-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Terry R, Hansen L, Masliah E. Structural basis of the cognitive alterations in Alzheimer disease. In: Terry R, Katzman R, editors. Alzheimer disease. New York: Raven Press; 1994. pp. 179–196. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Trojanowski J, Schmidt M, Shin R-W, Bramblett G, Rao D, Lee V-Y. Altered Tau and neurofilament proteins in neurodegenerative diseases: diagnostic implications for Alzheimer’s disease and Lewy body dementias. Brain Pathol. 1993;3:45–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1993.tb00725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Phosphorylation of neuronal cytoskeletal proteins in Alzheimer’s disease and Lewy body dementias. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;747:92–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb44403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Veinbergs I, Mante M, Mallory M, Masliah E. Neurotrophic effects of Cerebrolysin in animal models of excitotoxicity. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2000;59:273–280. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6781-6_29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ. A beta oligomers—a decade of discovery. J Neurochem. 2007;101:1172–1184. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Weaver CL, Espinoza M, Kress Y, Davies P. Conformational change as one of the earliest alterations of tau in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:719–727. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wei ZH, He QB, Wang H, Su BH, Chen HZ. Meta-analysis: the efficacy of nootropic agent Cerebrolysin in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neural Transm. 2007;114:629–634. doi: 10.1007/s00702-007-0630-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wen Y, Yang SH, Liu R, Perez EJ, Brun-Zinkernagel AM, Koulen P, Simpkins JW. Cdk5 is involved in NFT-like tauopathy induced by transient cerebral ischemia in female rats. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1772:473–483. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Woods YL, Cohen P, Becker W, Jakes R, Goedert M, Wang X, Proud CG. The kinase DYRK phosphorylates protein-synthesis initiation factor eIF2Bepsilon at Ser539 and the microtubule-associated protein tau at Thr212: potential role for DYRK as a glycogen synthase kinase 3-priming kinase. Biochem J. 2001;355:609–615. doi: 10.1042/bj3550609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.