Abstract

Objective

Skeletal muscle AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)α2 activity is impaired in obese, insulin resistant individuals during exercise. We determined whether this defect contributes to the metabolic dysregulation and reduced exercise capacity observed in the obese state.

Design

C57BL/6J wild-type (WT) mice and/or mice expressing a kinase dead AMPKα2 subunit in skeletal muscle (α2-KD) were fed chow or high fat (HF) diets from 3–16 weeks (wks) of age. At 15wks mice performed an exercise stress test to determine exercise capacity. In WT mice, muscle glucose uptake and skeletal muscle AMPKα2 activity was assessed in chronically catheterized mice (carotid artery/jugular vein) at 16wks. In a separate study, HF-fed WT and α2-KD mice performed 5wks of exercise training (from 15–20wks of age) to test whether AMPKα2 is necessary to restore work tolerance.

Results

HF-fed WT mice had reduced exercise tolerance during an exercise stress test, and an attenuation in muscle glucose uptake and AMPKα2 activity during a single bout of exercise (p<0.05 vs. chow). In chow-fed α2-KD mice running speed and time were impaired ~45% and ~55%, respectively (p<0.05 vs. WT chow); HF feeding further reduced running time ~25% (p<0.05 vs. α2-KD chow). In response to 5wks of exercise training, HF-fed WT and α2-KD mice increased maximum running speed ~35% (p<0.05 vs. pre-training) and maintained body weight at pre-training levels, whereas body weight increased in untrained HF WT and α2-KD mice. Exercise training restored running speed to levels seen in healthy, chow-fed mice.

Conclusion

HF feeding impairs AMPKα2 activity in skeletal muscle during exercise in vivo. While this defect directly contributes to reduced exercise capacity, findings in HF-fed α2-KD mice show that AMPKα2-independent mechanisms are also involved. Importantly, α2-KD mice on a HF-fed diet adapt to regular exercise by increasing exercise tolerance, demonstrating that this adaptation is independent of skeletal muscle AMPKα2 activity.

Keywords: obesity, muscle glucose uptake, exercise tolerance, exercise training, diet

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is a primary risk factor for disease states associated with the Metabolic Syndrome (i.e. Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease), and regular physical exercise has long been recognized as an essential component in the treatment of obesity1. A limiting factor for exercise as a therapeutic option is that obesity is characterized by impaired exercise tolerance, yet the limiting factor(s) responsible for this phenomenon is unclear. One enzyme that appears to play a significant role in the promotion of exercise tolerance is the serine-threonine AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), whose activation is increased in response to elevations in metabolic cellular stress2. In lean otherwise healthy mice expressing a kinase-dead form of the catalytic AMPKα2 subunit in skeletal muscle (α2-KD), exercise tolerance is markedly impaired3,4. AMPKα2 activity is also impaired in skeletal muscle of obese individuals during moderate intensity exercise5; however, whether this defect directly contributes to the reduced exercise capacity observed under obese conditions is unknown.

Here we utilized wild type (WT) and α2-KD mice to elucidate the role of AMPKα2 in the regulation of exercise tolerance under high fat (HF) fed, obese conditions. We hypothesized that (1) diet-induced obesity would significantly impair skeletal muscle AMPKα2 activity during exercise in vivo, and (2) that this impairment in skeletal muscle AMPKα2 activity significantly contributes to exercise intolerance. Regular physical activity is a common therapeutic recommendation for obese individuals6. Thus, we also tested whether a five week exercise training regimen would be effective in increasing exercise tolerance in HF-fed WT and α2-KD mice.

METHODS

Animal Maintenance

All procedures were approved by the Vanderbilt University Animal Care and Use Committee. Male and female C57BL/6J α2-KD mice7 and WT littermate mice were studied. Twenty-one days after birth, littermates were separated by gender and maintained in microisolator cages. Following separation, mice were fed a standard chow (5.5% fat by weight; 5001 Laboratory Rodent Diet, Purina, USA) or HF diet (35.5% fat by weight; diet F3282, Bio-Serv Inc., Frenchtown, USA) and had access to water ad libitum until they were 16–20 weeks of age.

Exercise Stress Test

In chow- and HF-fed WT and α2-KD mice, peak oxygen consumption (V̇O2peak) was assessed at 15 weeks of age using an exercise stress test protocol as previously described3. Briefly, following a 10 min acclimation period two days prior to the stress test, mice were placed in an enclosed single lane treadmill connected to Oxymax oxygen and carbon dioxide sensors (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, USA). Following a 30 min basal period, mice commenced running at 10 m•min−1 on a 0% incline. Running speed was increased by 4 m•min−1 every 3 min until mice reached exhaustion, defined as the point whereby mice remained at the back of the treadmill on an electric shock pad for 5s. Body weight was measured prior to the V̇O2peak test, and body composition was assessed using a mq10 NMR analyzer (Bruker Optics, The Woodlands, USA). All oxygen consumption measurements were expressed per kilogram of lean body mass (kgLBM).

Acute Exercise

To examine whether a HF diet impaired skeletal muscle glucose uptake and AMPKα2 activation during acute exercise in WT mice, 5hr fasted 16 week old chow- and HF-fed WT mice either remained sedentary on a treadmill or performed a single bout of treadmill exercise for 30 min at 16 m·min−1 (0% incline). Five days prior to the exercise bout mice were chronically catheterized (carotid artery and jugular vein) as described previously3,8. Fasting blood glucose was determined after the 5hr fast (t = 0 min) using a hand held glucose monitor (Accu-Chek Advantage, Roche, USA). At t = 5 min mice were injected with a bolus containing 13µCi of 2-[14C]deoxyglucose (2-[14C]DG) into the jugular vein. Arterial blood samples were collected at t = 10, 15, 20 and 30 min for measurement of glucose and plasma 2-[14C]DG levels. At t = 30 min, mice were anaesthetized with an intravenous injection of pentobarbital (3mg) and the gastrocnemius muscle was rapidly dissected, freeze-clamped in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until analysis.

Exercise Training

At 15 weeks of age, HF-fed WT and α2-KD mice performed an exercise stress test, and then were separated into two groups. One group performed exercise training for five weeks, while the other remained sedentary for five weeks. The exercise training utilized a gradual overload protocol and ran for five days per week. Specifically, running time and speed were increased such that by the end of weeks 16, 17, 18, 19, and 20 mice were running on a treadmill for 60 min at 50, 60, 70, 80 and 90% of maximum pre-training running speed, respectively. Sedentary mice were placed on an apparatus placed just above the treadmill in an adjacent lane to exercising mice. Following the five week period, both groups repeated the exercise stress test performed at week 15.

Plasma and Tissue Analyses

Plasma 2-[14C]DG radioactivity was assessed following deproteinization, and accumulation of phosphorylated 2-[14C]DG in the gastrocnemius was determined as previously described3. Indices for glucose metabolism (Rg) and clearance (Kg) were determined in chow- and HF-fed WT mice as previously described3.

Whole cell lysates were prepared as previously described3 using a lysis buffer containing 50mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1mM EDTA, 1mM EGTA, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 1mM DTT, 1× HALT protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific, USA). Nuclear and cytosolic fractions were prepared using the methods of McGee et al.9. Gastrocnemius samples were homogenized in Buffer A (250µM sucrose, 10mM NaCl, 3mM MgCl, 1mM DTT, 1× HALT protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail) using a hand-held pellet pestle and centrifuged at 500 g. The supernatant (cytosolic fraction) was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. The pellet was resuspended in Buffer B (50mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 1mM EGTA, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 50mM MgCl, 1mM DTT, 1× HALT protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail), kept on ice for 10 min and centrifuged at 3000 g. The resulting supernatant (nuclear fraction) was snap frozen and stored at −80°C. Characterization of the nuclear and cytosolic fraction was verified via immunoblotting, with histone 1 (Abcam, USA) being enriched in nuclear fractions, and glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; Abcam) being enriched in cytosolic fractions.

AMPK Activity Assay

AMPKα2 was immunoprecipitated using 200µg of protein, 2µg of a rabbit AMPKα2 polycolonal antibody (Abcam), and immobilized Recomb protein A beads (Thermo Scientific). AMPK activity in the immune complexes were measured for 20 min at 30°C (within the pre-determined linear range) in the presence of 200µM AMP, and calculated as picomoles of phosphate incorporated into the SAMS peptide (100µM; GenWay Biotech, USA) per min per mg of protein subjected to immunoprecipitation.

Immunoblotting

AMPKα2 protein expression was determined from immunoprecipitated samples from whole cell lysates, or from 20µg of nuclear and 40µg of cytosolic fractions. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC)β expression and phosphorylation was assessed from 200µg of whole cell lysate that had been affinity purified overnight at 4°C using strepdavidin agarose beads (Invitrogen, USA). Proteins were separated using NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris Gels (Invitrogen) and transferred to PVDF membranes. Blots were probed with an anti-AMPKα2 goat polyclonal antibody (1:100; Santa Cruz, USA), anti-AMPKα Thr172 rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:100; Cell Signaling, USA), or an anti-ACCβ Ser221 rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:100; Cell Signaling). Antibody binding was detected with an IRDye™ 800-conjugated anti-goat and anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Rockland, USA). ACCβ protein expression was detected using IRDye™ 800-labeled streptavidin (Rockland).

Statistical Analyses

Data are mean ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M). Statistical analysis was performed using a student t-test, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), or two-way repeated measures ANOVA where appropriate with the statistical software package SigmaStat. If the ANOVA was significant (P<0.05), specific differences were located using Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) test.

RESULTS

Obesity impairs exercise capacity

At 16 weeks of age HF-fed WT mice weighed more than chow-fed WT mice (37±2 vs. 24±2g, p<0.001) due to greater fat mass (33±2 vs. 9±2% body weight, p<0.001). In response to an exercise stress test, HF-fed WT mice were exercise intolerant as evidenced by impairments in running speed (30±1 vs. 38±1 m•min−1 for HF and chow, respectively; p<0.001), running time (17±1 vs. 23±1 min; p<0.001), and a ~40% impairment in V̇O2peak (77±6 vs. 127±5 ml•kgLBM−1•min−1; p<0.05).

Obesity impairs the exercise-induced increase in skeletal muscle glucose uptake and AMPKα2 activity in vivo

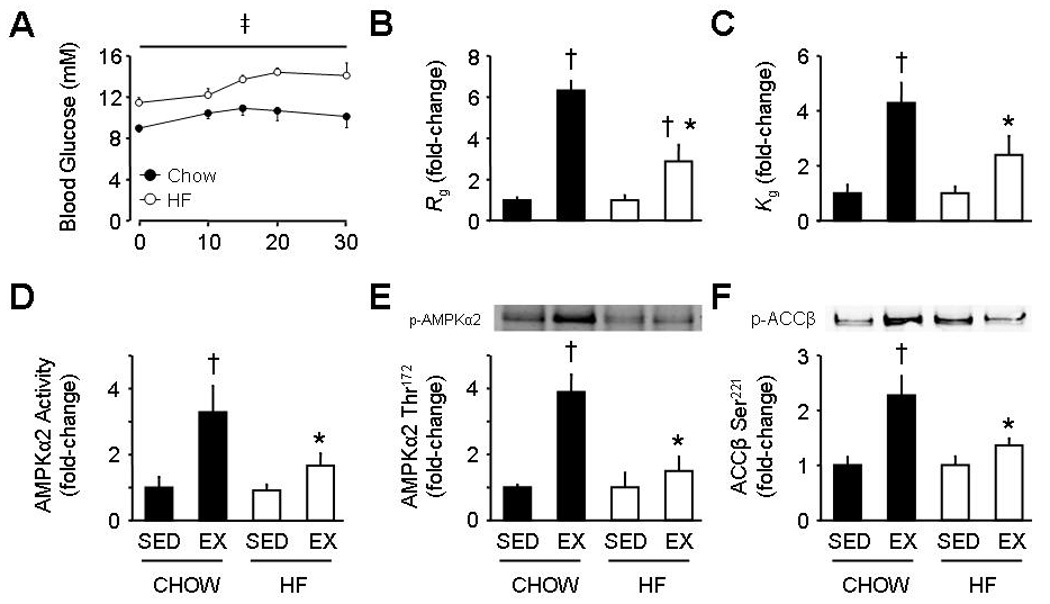

In the sedentary state blood glucose was higher in HF-fed mice compared to chow-fed controls (10.7±0.5 vs. 9.1±0.9 mM during the 30 min sedentary period; p<0.05). In response to 30min of treadmill exercise blood glucose significantly increased over time in chow- and HF-fed mice, although blood glucose was consistently elevated in HF-fed mice (Figure 1A). The gastrocnemius muscle glucose metabolic index (Rg; Figure 1B) and gastrocnemius glucose clearance (Kg; Figure 1C) increased ~6-fold and ~4-fold, respectively, during exercise in chow-fed mice. Increases with exercise were significantly attenuated in HF-fed mice.

Figure 1.

Blood glucose levels during exercise (A), and gastrocnemius glucose uptake (Rg; B), glucose clearance (Kg; C), AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)α2 activity (D), AMPKα2 Thr172 phosphorylation (E), and acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC)β Ser221 phosphorylation at rest (SED) and in response to a 30 min bout of exercise (EX) in 16 week old C57BL/6J mice fed a chow or high-fat (HF) diet. Data are mean ± S.E.M for N=5–7 per group. In B–F data are expressed as fold-change from corresponding SED. ‡ main effect for chow vs. HF, p<0.05; † p<0.05 vs. corresponding SED; * p<0.05 vs. corresponding chow.

Under basal conditions, no differences were observed for whole cell AMPKα2 activity or AMPKα2 Thr172 phosphorylation in the gastrocnemius of chow- and HF-fed WT mice. Basal levels of whole cell ACCβ Ser221 phosphorylation were slightly, but not significantly elevated in HF-fed WT mice (p=0.3 vs. chow-fed WT). AMPKα2 and ACCβ protein expression were similar between groups. In chow-fed WT mice, exercise significantly increased AMPKα2 activity (Figure 1D), AMPKα2 Thr172 phosphorylation (Figure 1E), and ACCβ Ser221 phosphorylation (Figure 1F). In contrast, these exercise-induced increases were all ablated in HF-fed WT mice.

We next assessed whether the impairment in whole cell AMPKα2 activity was localized to specific subcellular compartments. Nuclear AMPKα2 activity in response to exercise tended to increase in chow-fed mice (p=0.09 vs. sedentary); nuclear AMPKα2 activity in response to exercise was significantly reduced in HF-fed mice compared to chow-fed mice (Figure 2A). Likewise, cytosolic AMPKα2 activity increased during exercise in chow-fed mice, whereas no increase was seen in HF-fed mice (Figure 2B). The suppressed nuclear and cytosolic AMPKα2 activity in HF-fed mice was not due to reduced AMPKα2 protein expression (Figure 2C and 2D). Indeed, the exercise-induced increase in nuclear AMPKα2 activity of chow-fed WT mice occurred despite lower protein levels of AMPKα2.

Figure 2.

Nuclear AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) α2 activity (A), cytosolic AMPKα2 activity (B), nuclear AMPKα2 protein expression (C), and cytosolic AMPKα2 protein expression in gastrocnemius muscle of 16 week old C57BL/6J mice fed a chow or high-fat (HF) diet. Mice either remained sedentary (SED) or performed 30 min of treadmill exercise (EX). Data are mean ± S.E.M for N=6–8 per group. † p<0.05 vs. corresponding SED; * p<0.05 vs. corresponding chow.

AMPK-dependent and -independent factors regulate exercise capacity in obese states

Our findings above demonstrate that a HF diet impairs exercise capacity during an exercise stress test. To determine the degree to which the impaired exercise capacity in HF-fed mice was directly dependent upon impaired activation of AMPKα2, chow- and HF-fed α2-KD mice performed an exercise stress test. α2-KD mice were utilized as AMPKα2 activity is essentially abolished in skeletal muscle of these mice both at rest and in response to moderate intensity exercise in vivo3. In α2-KD mice HF-feeding resulted in similar changes in body composition to that of HF-fed WT mice (data not shown). As expected3, chow-fed α2-KD mice had impairments in running speed and running time compared to chow-fed WT mice (~45 and ~55% reduction, respectively; p<0.001). V̇O2peak during the exercise stress test was also reduced in chow-fed α2-KD vs. WT mice (Figure 3); however, V̇O2peak for chow-fed α2-KD mice was higher than that observed in HF-fed WT mice. HF feeding further reduced V̇O2peak in α2-KD mice; in fact, no significant increase in V̇O2 was observed during the exercise stress test (Figure 3). HF feeding also reduced running time in α2-KD mice (7.6±0.9 vs. 10.0±0.9 min for HF-fed and chow α2-KD mice, respectively; p<0.05), while there was a tendency for reduced maximum running speed (18±1 vs. 21±1 m•min−1; p=0.06).

Figure 3.

Oxygen consumption (V̇O2) at rest or exhaustion in 16 week old C57BL/6J mice. Wild-type (WT) and AMP-activated protein kinase α2 kinase-dead (α2-KD) mice fed a chow or high-fat (HF) diet performed an exercise stress test on a treadmill (see Methods). Data are mean ± S.E.M for N=8–9 per group. † p<0.05 vs. corresponding basal; * p<0.05 vs. WT chow; ** p<0.05 vs. WT chow and WT HF; *** p<0.05 vs. WT chow, WT HF, and α2-KD chow. kgLBM, kilograms of lean body mass.

In chow- and HF-fed α2-KD mice the increase in V̇O2 (ΔV̇O2) during the exercise stress test was 22±4 and 5±2 ml•kgLBM−1•min−1, respectively. As AMPKα2 is not activated in these mice, the difference between these variables (17±2 ml•kgLBM−1•min−1) represents an AMPKα2-independent component with regards to ΔV̇O2 during an exercise stress test. In WT mice, ΔV̇O2 was impaired by 40±2 ml•kgLBM−1•min−1 in response to HF feeding. Therefore, ~45% of this impairment (i.e. ~17 ml•kgLBM−1•min−1) in HF-fed WT mice is due to AMPKα2-independent mechanisms (i.e. the remaining ~55% of the impaired ΔV̇O2 in HF-fed WT mice is AMPKα2-dependent). The contributions of AMPKα2-dependent and independent components are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Oxidative capacity during exercise is regulated via AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) α2-dependent and -independent components. ΔV̇O2, change in oxygen consumption; WT, wild-type; α2-KD, AMPKα2 kinase-dead; HF, high fat. kgLBM, kilograms of lean body mass.

Exercise training improves exercise capacity of HF-fed mice independently of AMPKα2 in skeletal muscle

To determine whether normal AMPKα2 activity is necessary for a training-induced increase in exercise capacity, HF-fed WT and α2-KD mice performed five weeks of exercise training or remained sedentary beginning at 15 weeks of age. Sedentary WT and α2-KD mice significantly increased body weight over the five week period (Table 1), and had no improvement in maximum running speed (Figure 5). In contrast, at 20 weeks trained HF-fed WT mice maintained body weight at pre-training levels (Table 1), and increased maximum running speed by 34±6% (Figure 5). Indeed, maximum running speed returned to levels observed in lean, healthy untrained WT mice. While in absolute terms running speed remained impaired in HF-fed α2-KD mice post-training, trained α2-KD mice had a similar relative increase in maximum running speed (35±6% vs. week 15) when compared with trained WT mice. As with HF-fed WT mice, trained HF-fed α2-KD mice were able to maintain body weight at pre-training levels (Table 1). Thus, mice expressing a catalytically inactive AMPKα2 subunit in skeletal muscle respond normally to exercise training. The fact that α2-KD mice elicited a similar relative increase in exercise capacity post-training, and were also able to maintain body weight, shows that these adaptations to training occur independently of skeletal muscle AMPKα2.

Table 1.

Body weight and body composition measurements of high-fat (HF)-fed C57BL/6J wild-type (WT) mice, and HF-fed C57BL/6J mice expressing a kinase-dead AMP-activated protein kinase α2 subunit (α2-KD) in skeletal muscle. Mice either remained sedentary or performed treadmill exercise training from 15–20 weeks of age (see Methods).

| Body weight (g) | Fat mass (g) | Lean mass (g) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT Sedentary | |||

| Week 15 | 39±5 | 12.8±2.8 | 24.1±1.6 |

| Week 20 | 42±5* | 15.3±2.9* | 24.1±2.1 |

| WT Trained | |||

| Week 15 | 35±2 | 12.2±1.6 | 21.0±0.4 |

| Week 20 | 32±2 | 10.4±1.6 | 19.8±0.7 |

| α2-KD Sedentary | |||

| Week 15 | 41±5 | 14.6±3.6 | 23.7±1.6 |

| Week 20 | 44±5* | 17.6±3.8* | 23.9±1.8 |

| α2-KD Trained | |||

| Week 15 | 36±3 | 12.3±2.5 | 21.9±1.2 |

| Week 20 | 36±2 | 13.4±1.8 | 20.9±0.9 |

Data are mean ± S.E.M for N=4–5 per group.

p<0.05 vs. corresponding Week 15 value.

Figure 5.

Effect of 5wk exercise training on maximum running speed of high-fat (HF) fed wild-type (WT) and HF fed AMP-activated protein kinase α2 kinase-dead (α2-KD) mice. Mice performed an exercise stress test at week 15, and then either remained sedentary or performed treadmill exercise training (see Methods) for 5wk. An exercise stress test was performed at week 20. Data for Chow (untrained) was taken from the acute exercise studies. Data are mean ± S.E.M for N=4–5 per group. † p<0.001 vs. corresponding Week 15 group; ** p<0.001 vs. corresponding sedentary Week 20 group; * p<0.001 vs. HF WT.

DISCUSSION

Regular physical exercise has long been recognized as an essential component in the treatment of obesity, due to the beneficial effects on weight maintenance/reduction, and lowering the risk of developing Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease1,6. Here we show that skeletal muscle AMPKα2 plays a significant role in ones ability to fully utilize exercise as a preventative or interventional treatment option. Indeed, we show that the suppression in AMPKα2 activation observed during acute exercise under obese, insulin resistant conditions plays a significant role in the impaired exercise capacity also observed under these conditions. However, the physiological adaptation to exercise training occurs regardless of whether AMPKα2 is activated, as a catalytically inactive AMPKα2 subunit does not attenuate the relative increase in exercise capacity seen following five weeks of exercise training. Thus, while AMPKα2 plays a key role in the regulation of exercise capacity, factors independent of AMPKα2 are also involved.

In the present study we utilized an exercise stress test, a non-invasive tool that has long been used to diagnose certain disease states in humans10,11, to identify AMPKα2-dependent and -independent components involved in the regulation of exercise capacity. Both diet- and genotype-specific effects were observed in the present study. Taken together with previous observations in lean healthy mice expressing a catalytically inactive AMPKα2 subunit3,7,12, as well as other genetically modified mice with impaired AMPKα2 activation13,14 it can be seen that skeletal muscle AMPKα2 clearly plays a role in the regulation of exercise capacity in vivo. Likewise, impaired AMPKα2 activity in obese WT mice was also associated with a reduction in exercise capacity; however, our finding that HF feeding further reduced exercise capacity in α2-KD mice shows that AMPKα2-independent mechanisms also regulate exercise capacity. The relative contributions of AMPK-dependent and independent components are shown in Figure 4. Our data clearly show that the dysregulation of AMPKα2 in skeletal muscle, whether in lean or obese states, significantly reduces exercise tolerance in vivo. This highlights the significant role of AMPKα2 in the physiological response to exercise.

The finding that the increase in V̇O2 was fully suppressed during the exercise stress test in HF-fed α2-KD mice is remarkable. It is unlikely that this phenomenon is due to cardiac dysfunction arising from expression of the α2-KD transgene in cardiac muscle, as glucose uptake, heart rate, and cardiac output are normal during exercise in chow-fed α2-KD mice3. We have shown that chow-fed α2-KD mice exhibit vascular dysfunction, as evidenced by the inability to increase fractional cardiac output (assessed via microsphere deposition) in skeletal muscle during exercise3. It is possible that HF feeding per se exacerbated this impairment in vascular dysfunction in α2-KD mice. Regardless, it is clear that these mice are heavily reliant on anaerobic sources in order to perform exercise; however, the factor(s) responsible for this phenomenon is unclear. While chow-fed α2-KD mice also have a greater reliance on anaerobic sources during exercise – due to impairments in complex I and IV activities of the electron transport chain (ETC)3 – it has recently been shown that some of these differences are not apparent in HF-fed α2-KD and WT mice15. Indeed, expression of different ETC complexes is actually increased in WT and α2-KD mice following HF feeding15. Nevertheless, diet-induced obesity is characterized by enhanced release of reactive oxidative species and impaired mitochondrial function16; however, it is unclear whether AMPKα2 plays a role in this process17. Thus, while the exact mechanism(s) accounting for the suppression of V̇O2 during the exercise stress test in HF-fed α2-KD mice is unclear, it is highly likely that there is an element of vascular dysfunction.

An important finding from the present study was that AMPKα2 activity was impaired in different subcellular compartments (i.e. nuclear and cytosolic) of HF-fed WT mice during exercise. These differences were not due to reduced AMPKα2 expression within these compartments. Indeed, nuclear AMPKα2 expression was reduced in chow-fed WT mice during exercise when compared to HF-fed WT mice, yet nuclear AMPKα2 activity tended to be higher in chow-fed WT mice under these conditions. The functional result of impaired AMPKα2 activity in these different compartments has important implications. Cell culture studies have shown that AMPK is at least partially required for GLUT-4 transcription18. Likewise, the exercise-induced increase in PGC-1α mediated nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes is impaired in obese versus lean individuals, a phenomenon associated with impaired AMPK activation during exercise in obese individuals19. In contrast, evidence from global AMPKα2 knockout mice suggests that AMPKα2 is not required for certain metabolic adaptations to exercise training. Indeed, in ampkα 2−/− mice key enzymes involved in glucose metabolism (i.e. GLUT4 and hexokinase (HK) II) increase in a similar manner to WT mice following 28 days of wheel running20. Consistent with these findings, we show that the capacity to improve exercise performance is retained following exercise training in HF-fed mice with impaired AMPKα2 activity.

As mentioned above, both HF-fed WT and α2-KD mice are able to increase exercise capacity in response to exercise training. Given that AMPKα2 activity is essentially abolished in α2-KD mice3, this training-induced increase in exercise capacity clearly occurs via AMPKα2-independent mechanisms. This is evidenced by the almost identical relative increase in maximum running speed between genotypes (~35%) when compared to respective pre-training levels. This is the first study to show that obese mice lacking a catalytically active AMPKα2 subunit can increase exercise capacity in response to exercise training. In the present study, the training protocol employed involved mice exercising for the same amount of time at the same relative intensity. This meant that WT mice were constantly exercising at a greater absolute running speed than α2-KD mice. We chose to exercise α2-KD mice at the same relative work intensity as WT mice, since exercising at the same relative intensity elicits similar increases in muscle cellular stress between the two genotypes, whereas at the same absolute running speed cellular stress is lower in WT mice3. It should be noted that in the present study we assessed the extreme condition of HF fed mice with and without a mutated AMPKα2 subunit. It is reasonable to assume that under the less extreme condition of chow feeding, lean mice would adapt to regular exercise as well. Importantly, we show that HF-fed obese mice were able to obtain a normal capacity to perform physical exercise after five weeks of training, despite reduced and even absent AMPK activity. This phenomenon is likely to be at least partially due to increases in mitochondrial markers, GLUT-4, and HKII, all of which increase in an AMPKα2-independent manner following exercise training20.

In skeletal muscle AMPKα2 has been hypothesized as a key regulator of muscle glucose uptake. Here we demonstrate that in HF-fed WT mice a partial impairment in the exercise-induced increase in Rg occurred concomitantly with impaired activation of AMPKα2. It is notable that the impaired AMPKα2 activity in HF-fed WT mice occurred even though these mice exercised at a higher percentage of maximum running speed. HF-fed WT mice were exercising at ~50% of maximum running speed whereas chow-fed WT mice were exercising at ~40% of maximum running speed, further highlighting the inhibitory effect of HF feeding on skeletal muscle AMPKα2 activation during exercise in vivo. Despite the impairment in AMPKα2 activity in HF-fed mice during exercise, it is unlikely that this phenomenon directly accounted for the reduction in the exercise-induced increase in Rg. Previous studies from our laboratory3 and others21 have demonstrated that the tissue extraction of glucose and GLUT-4 translocation during exercise in healthy α2-KD mice occur at levels similar to that of WT mice. Rather, the attenuation of muscle glucose uptake during exercise in α2-KD mice is due to an impaired fraction of cardiac output to skeletal muscle, and thus reduced glucose delivery, to skeletal muscle. It is notable that HF-fed WT mice, that have impaired AMPKα2 activation during exercise, are also characterized by vascular dysfunction22.

In conclusion, principles of exercise testing were uniquely applied to mice expressing a kinase-dead AMPKα2 protein in skeletal muscle to determine the mechanisms of exercise intolerance in response to HF feeding. The exercise intolerance arising from HF feeding was due to AMPKα2-dependent and -independent dysfunction. The AMPKα2-dependent exercise-intolerance in HF-fed mice was due to diminished AMPKα2 activity in both nuclear and cytosolic fractions of skeletal muscle during exercise. Nevertheless, ablation of AMPKα2 activity in skeletal muscle did not prevent the restoration of normal work tolerance in HF-fed mice in response to exercise training. This emphasizes the value of regular physical activity even in subjects in whom muscle AMPKα2 activity is reduced, such as it is in obesity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants U24 DK-59637 and R01 DK-54902 (to D.H.W). R.S. Lee-Young was supported by a Mentor-Based Fellowship from the American Diabetes Association. Current address for J.E. Ayala: Diabetes and Obesity Research Center, Burnham Institute for Medical Research, FL, U.S.A. Current address for P.T. Fueger: Department of Pediatrics, Department of Cellular and Integrative Physiology, and Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, U.S.A.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors declare that there are no competing financial interests in relation to the work described.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sigal RJ, Kenny GP, Wasserman DH, Castaneda-Sceppa C, White RD. Physical Activity/Exercise and Type 2 Diabetes: A consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1433–1438. doi: 10.2337/dc06-9910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinberg GR, Kemp BE. AMPK in Health and Disease. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:1025–1078. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee-Young RS, Griffee SR, Lynes SE, Bracy DP, Ayala JE, McGuinness OP, et al. Skeletal Muscle AMP-Activated Protein Kinase is Essential for the Metabolic Response to Exercise In Vivo. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:23925–23934. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.021048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mu J, Barton ER, Birnbaum MJ. Selective suppression of AMP-activated protein kinase in skeletal muscle: update on 'lazy mice'. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31:236–241. doi: 10.1042/bst0310236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sriwijitkamol A, Coletta DK, Wajcberg E, Balbontin GB, Reyna SM, Barrientes J, et al. Effect of Acute Exercise on AMPK Signaling in Skeletal Muscle of Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes: A Time-Course and Dose-Response Study. Diabetes. 2007;56:836–848. doi: 10.2337/db06-1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blaak EE, Saris WHM. Substrate oxidation, obesity and exercise training. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2002;16:667–678. doi: 10.1053/beem.2002.0226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mu J, Brozinick JT, Jr, Valladares O, Bucan M, Birnbaum MJ. A role for AMP-activated protein kinase in contraction- and hypoxia-regulated glucose transport in skeletal muscle. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1085–1094. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayala JE, Bracy DP, McGuinness OP, Wasserman DH. Considerations in the Design of Hyperinsulinemic-Euglycemic Clamps in the Conscious Mouse. Diabetes. 2006;55:390–397. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.02.06.db05-0686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGee SL, Howlett KF, Starkie RL, Cameron-Smith D, Kemp BE, Hargreaves M. Exercise increases nuclear AMPK α2 in human skeletal muscle. Diabetes. 2003;52:926–928. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.4.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wasserman K, Hansen JE, Sue DY, Casaburi R, Whipp BJ. Principles of exercise testing and interpretation. 3rd edn. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wasserman K, Sietsema KE. Assessing cardiac function by gas exchange. Cardiology. 1988;75:307–310. doi: 10.1159/000174390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujii N, Seifert MM, Kane EM, Peter LE, Ho RC, Winstead S, et al. Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in exercise capacity, whole body glucose homeostasis, and glucose transport in skeletal muscle - insight from analysis of a transgenic mouse model. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;77:S92–S98. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2007.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee-Young RS, Ayala JE, Hunley CF, James FD, Bracy DP, Kang L, et al. Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase is Central to Skeletal Muscle Metabolic Regulation and Enzymatic Signaling during Exercise In Vivo. Am J Physiol. 2010;298:R1399–R1408. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00004.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakamoto K, McCarthy A, Smith D, Green KA, Grahame Hardie D, Ashworth A, et al. Deficiency of LKB1 in skeletal muscle prevents AMPK activation and glucose uptake during contraction. EMBO J. 2005;24:1810–1820. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beck Jørgensen S, O’Neill H, Hewitt K, Kemp B, Steinberg G. Reduced AMP-activated protein kinase activity in mouse skeletal muscle does not exacerbate the development of insulin resistance with obesity. Diabetologia. 2009;52:2395–2404. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1483-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson EJ, Lustig ME, Boyle KE, Woodlief TL, Kane DA, Lin C-T, et al. Mitochondrial H2O2 emission and cellular redox state link excess fat intake to insulin resistance in both rodents and humans. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:573–581. doi: 10.1172/JCI37048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merry TL, Steinberg GR, Lynch GS, McConell GK. Skeletal muscle glucose uptake during contraction is regulated by nitric oxide and ROS independently of AMPK. Am J Physiol. 2010;298:E577–E585. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00239.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGee SL, van Denderen BJW, Howlett KF, Mollica J, Schertzer JD, Kemp BE, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase regulates GLUT4 transcription by phosphorylating histone deacetylase 5. Diabetes. 2008;57:860–867. doi: 10.2337/db07-0843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Filippis E, Alvarez G, Berria R, Cusi K, Everman S, Meyer C, et al. Insulin-resistant muscle is exercise resistant: evidence for reduced response of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes to exercise. Am J Physiol. 2008;294:E607–E614. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00729.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jorgensen SB, Treebak JT, Viollet B, Schjerling P, Vaulont S, Wojtaszewski JF, et al. Role of AMPKα2 in basal, training-, and AICAR-induced GLUT4, hexokinase II, and mitochondrial protein expression in mouse muscle. Am J Physiol. 2007;292:E331–E339. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00243.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maarbjerg SJ, Jorgensen SB, Rose AJ, Jeppesen J, Jensen TE, Treebak JT, et al. Genetic impairment of α2-AMPK signaling does not reduce muscle glucose uptake during treadmill exercise in mice. Am J Physiol. 2009;297:E924–E934. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90653.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim F, Pham M, Maloney E, Rizzo NO, Morton GJ, Wisse BE, et al. Vascular Inflammation, Insulin Resistance, and Reduced Nitric Oxide Production Precede the Onset of Peripheral Insulin Resistance. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1982–1988. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.169722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]