Abstract

BACKGROUND

Long QT syndrome (LQTS) is a potentially lethal, highly treatable cardiac channelopathy for which genetic testing has matured from discovery to translation and now clinical implementation.

OBJECTIVES

Here we examine the spectrum and prevalence of mutations found in the first 2,500 unrelated cases referred for the FAMILION® LQTS clinical genetic test.

METHODS

Retrospective analysis of the first 2,500 cases (1,515 female patients, average age at testing 23 ± 17 years, range 0 to 90 years) scanned for mutations in 5 of the LQTS-susceptibility genes: KCNQ1 (LQT1), KCNH2 (LQT2), SCN5A (LQT3), KCNE1 (LQT5), and KCNE2 (LQT6).

RESULTS

Overall, 903 referral cases (36%) hosted a possible LQTS-causing mutation that was absent in >2,600 reference alleles; 821 (91%) of the mutation-positive cases had single genotypes, whereas the remaining 82 patients (9%) had >1 mutation in ≥1 gene, including 52 cases that were compound heterozygous with mutations in >1 gene. Of the 562 distinct mutations, 394 (70%) were missense, 428 (76%) were seen once, and 336 (60%) are novel, including 92 of 199 in KCNQ1, 159 of 226 in KCNH2, and 70 of 110 in SCN5A.

CONCLUSION

This cohort increases the publicly available compendium of putative LQTS-associated mutations by >50%, and approximately one-third of the most recently detected mutations continue to be novel. Although control population data suggest that the great majority of these mutations are pathogenic, expert interpretation of genetic test results will remain critical for effective clinical use of LQTS genetic test results.

Keywords: Long QT syndrome, Genetic testing, Potassium channels, Sodium channels

Introduction

Congenital long QT syndrome (LQTS) comprises a distinct group of cardiac channelopathies characterized by QT prolongation on a 12-lead surface electrocardiogram (ECG) and increased risk for syncope, seizures, and sudden cardiac death in the setting of a structurally normal heart and otherwise healthy individual.1 The incidence of LQTS may be as high as 1 in 2,500 persons.2

To date, hundreds of nonsynonymous (amino acid altering, missense, nonsense, and frameshift) mutations and splice-site altering mutations have been identified in 12 LQTS-susceptibility or LQTS overlap-susceptibility genes.3–14 Although an estimated 20% of LQTS remains genetically elusive, approximately 75% of clinically definite LQTS is caused by mutations in 3 genes: KCNQ13 (LQT1), KCNH24 (LQT2), and SCN5A5 (LQT3), which encode the major pore-forming alpha subunit of the macromolecular channel complexes Kv7.1 (IKs), Kv11.1 (IKr), and Nav1.5 (INa), respectively. Similar comprehensive open reading frame/splice site analyses of ostensibly healthy individuals indicates that <3% of Caucasians and approximately 6% of African Americans have rare missense mutations as well.15,16

After the sentinel discovery of LQTS as a channelopathy in 1995,4,5 the next decade of LQTS genetic testing was performed in a few research laboratories worldwide and resulted in a score of publications detailing various genotype–phenotype relationships and the diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic implications derived from the genetic test results. Presently, the publicly available website (http://www.fsm.it/cardmoc) maintained by Priori lists 636 distinct LQTS-associated mutations as of February 1, 2009. The maturation from discovery to translation to clinical implementation has continued with the availability, since 2004 in North America, of clinical LQTS genetic testing through PGxHealth’s clinical test called the FAMILION® LQTS test, which provides comprehensive mutational analysis of the 3 major LQTS-susceptibility genes along with 2 minor genes (KCNE1 [LQT5] and KCNE2 [LQT6]).

The clinically available genetic test is a high-throughput, automated, bidirectional DNA sequencing-based assay that comprises analysis of 73 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplicons and over 12 kilobases of genetic sequence. Each amplicon in which a patient mutation is found is re-sequenced to ensure accuracy. In April 2008, LQTS genetic testing matured further as Blue Cross Blue Shield’s Technology Evaluation Center summary concluded that LQTS genetic testing has bona fide clinical utility rather than being merely investigational.17

Here, we examine the spectrum and prevalence of mutations found in the first 2,500 unrelated cases referred for LQTS genetic testing during the test’s first 4.5 years of availability.

Methods

Comprehensive mutational analysis of unrelated LQTS cases

Between May 2004 and October 2008, 2,500 unrelated patients (1,515 female patients, average age at testing 26 ± 17 years; 985 male patients, average age at testing 19 ± 15 years) were referred for LQTS clinical genetic testing through PGxHealth, a division of Clinical Data, Inc., New Haven, Connecticut. Tests were ordered by approximately 1,000 physicians, principally adult and pediatric heart rhythm specialists, other cardiologists, and geneticists in partnership with the patient’s cardiologist. Samples were accepted for genetic testing and included in this retrospective analysis regardless of the ordering physician’s index of suspicion or pre-test probability of a clinical diagnosis of LQTS. This retrospective, institutional review board–approved analysis is derived from de-identified data. The only uniformly available clinical variables are gender and age at genetic testing.

Patient genomic DNA was analyzed for mutations in all 60 translated exons and their splice site regions of KCNQ1, KCNH2, SCN5A, KCNE1, and KCNE2 using PCR and automated DNA sequencing. The test was validated and is performed in accordance with the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments Act. All PCR primers were designed with special care to avoid the phenomenon of allelic dropout, which can lead to a false-negative genetic test result.18 Insertions and deletions that span an amplicon or interfere with amplification are not detected.19,20

Mutation nomenclature

All putative LQTS-associated mutations and other variants were denoted using known and accepted nomenclature.21 For example, the single letter amino acid code was used to designate missense mutations (single amino acid substitutions) using the L250P format. Here, at amino acid position 250, the wild-type amino acid (L = leucine) is replaced by a proline (P) on one of the chromosomes. Frame-shift mutations resulting from nucleotide insertions or deletions were annotated using the R174fs + 105X format. Here, R174 represents the last properly encoded amino acid followed by a frame shift (fs) in the coding sequence, resulting in 105 miscoded amino acids before reaching a stop codon (X), resulting in a truncated protein containing a total of 279 amino acids.

A substitution of either the first or the last 2 nucleotides of a particular exon has the capacity to alter proper mRNA splicing, regardless of whether the nucleotide substitution codes for a different amino acid (missense mutation) produces a stop codon (nonsense mutation) or does not alter the open reading frame at all (i.e., a synonymous or silent single nucleotide substitution).22–24 As such, mutations involving this exonic portion of the splice site were considered as possible splicing mutations in this study and annotated as either missense/splice, nonsense/splice, or silent/splice mutations to distinguish them from intronic mutations predicted to disrupt splicing.

Topological placement of the mutations was done using a combination of Swissprot (http://ca.expasy.org/uniprot/) and recent studies of the linear topologies for each of the 3 main pore-forming alpha subunits.25–27 The Swissprot database provides generally accepted residue ranges corresponding with each ion-channel region and specialized subregions.

Defining mutation status

To be considered as a potential LQTS-causing mutation, the variant must disrupt either the open reading frame (i.e., missense, nonsense, insertion/deletion, or frame shift mutations) or the splice site (poly-pyrimidine tract, splice acceptor or splice donor recognition sequences). In addition to the exonic splice sites described above, the acceptor splice site was defined as the 3 intronic nucleotides preceding an exon (designated as IVS-1, -2, or -3) and the donor splice site as the first 5 intronic nucleotides after an exon (designated as IVS+1, +2, +3, +4, or +5).24 Additionally, single nucleotide substitutions (namely, a pyrimidine [C or T] for a purine [A or G]) within the poly-pyrimidine tract immediately preceding the acceptor splice site may be causative.28 As such, pyrimidine-to-purine substitutions in this region of the intron have been included as potentially pathogenic. For example, an IVS-7 Cytosine (C) that falls within the polypyrimidine tract and is substituted for an adenine (A) that would predictively disrupt the poly-pyrimidine tract and consequently result in aberrant splicing would be included as a putative pathogenic mutation. Hence, single nucleotide substitutions that did not change the open reading frame (i.e., synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms/variants) and intronic nucleotide substitutions located outside of the splice site recognition sequence (i.e., beyond IVS−3 or IVS+5) were excluded from consideration.

Additionally, the candidate mutation must not have been observed in a panel of now over 1,300 ostensibly healthy volunteers (>2,600 reference alleles; 47% Caucasian, 26% African American, 11% Hispanic, 10% Asian, and 6% unknown/other).15,16,29 As such, for the purpose of this article, the sole or concurrent presence of common or rare nonsynonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms such as P448R-KCNQ1, R176W-KCNH2, H558R-SCN5A, D85N-KCNE1, or Q9E-KCNE2 would not be designated as a pathogenic mutation resulting in LQT1, LQT2, LQT3, LQT5, or LQT6, respectively, despite there being evidence of slight abnormality or risk associated with some of these. Further, such polymorphisms would not be counted toward the assignment of compound or multiple mutation status to an individual.

Results

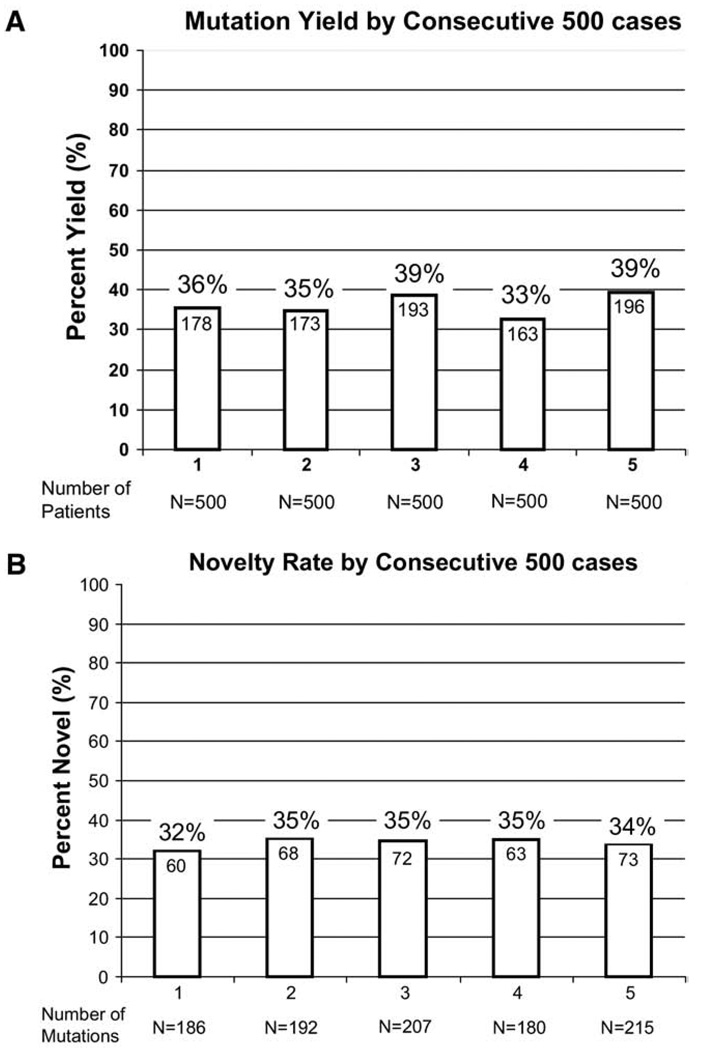

Overall, 903 of 2,500 (36%) unrelated LQTS referral cases had a positive genetic test with the identification of a putative LQTS-causing mutation that was absent in over 2,600 reference alleles. Although males were younger than females (19 ± 15 years compared to 26 ± 17 years, P < .0001) at the time of testing, there was no difference in yield of the genetic test between male (358 of 985, 36.3%) or female patients (545 of 1,515, 36.0%). The yield (approximately 36%) was similar between those physicians ordering at least 10 tests and those ordering fewer tests (data not shown). Further, the yield has remained consistent throughout the first 4.5 years of this clinically available test (36% for the first 500 cases and 39% for the most recent 500 cases, P = NS, Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Mutation detection yield and novelty rate over the life of the test. Comparing 5 consecutive groups of 500 cases, the bar graph in (A) depicts the frequency of positive genetic test results, ranging from 33% to 39%, and in (B) illustrates the novelty rate during the lifetime of the test, ranging from 32% to 35%. Each variant is counted as novel only in the first patient in whom it was discovered. Novelty was assessed relative to the web site (http://www.fsm.it/cardmoc) as of February 1, 2009.

Among the 903 genotype-positive patients, 821 (91%) had a single mutation: 386 in KCNQ1 (43%), 288 in KCNH2 (32%), 115 in SCN5A (13%), 24 in KCNE1, and 8 in KCNE2. The remaining 82 patients (9%) had >1 mutation, including 30 cases with multiple mutations in the same gene: KCNQ1 (19), KCNH2 (3), SCN5A (6), KCNE1 (1), and KCNE2 (1). Fifty-two cases were compound heterozygotes with mutations in >1 gene. Ten cases hosted 3 distinct mutations, some with 3 mutations all in the same gene. Male patients with multiple mutations (n = 43, 13 ± 9 years) were younger at testing than male patients with a single LQTS-associated mutation (n = 315, 18 ± 16 years, P < .005). There was no difference in age between female patients (n = 39, 25 ± 19 years) with multiple mutations compared with female patients with a single mutation (n = 506, 26 ± 17 years). Mutation-positive male patients were more likely to have multiple mutations than mutation-positive female patients (12% vs. 7%, P < .02).

In total, the 903 genotype-positive cases stemmed from 562 distinct LQTS-causing mutations: 199 distinct mutations in KCNQ1, 226 in KCNH2, 110 in SCN5A, 18 in KCNE1, and 9 in KCNE2 (Supplemental Tables 1 through 5). Notably, despite 10 years of research-based genetic testing that has generated over 636 mutations in the published record, over half of the mutations (336 of 562, 60%) were novel to this cohort, including 92 in KCNQ1, 159 in KCNH2, and 70 in SCN5A. Remarkably, the novelty rate has varied little during the lifetime of the test, ranging from 32% to 35% when comparing consecutive strata of 500 cases (Figure 1B) and considering each mutation novel only the first time it was observed. The rate of novel mutation discovery was lowest for KCNQ1 (data not shown).

The vast majority (76%) of the mutations were observed in a single index case, whereas 134 mutations (24%) were observed more than once in this cohort (Figure 2). The 5 most commonly observed LQTS-causing mutations were L266P-KCNQ1 seen in 30 unrelated patients, R518X-KCNQ1 in 24, R594Q-KCNQ1 in 15, G168R-KCNQ1 in 15, and E1784K-SCN5A in 15 unrelated patients (Figure 2). The possibility of more distant relatedness (founder effects) could not be ascertained in this study, which may even include close relatives for whom the comprehensive mutational analysis was ordered rather than family-specific tests after the proband was analyzed.

Figure 2.

LQTS-associated mutation frequency distribution. This bar graph summarizes the distribution of specific mutations among unrelated patients. The y axis depicts the number of distinct LQTS-associated mutations, and the x axis represents the number of unrelated patients. For example, the first column indicates that there were 166 distinct mutations, each observed only once. The last column indicates that 5 different LQTS-associated mutations were each seen in ≥11 unrelated patients. The inset shows the 5 most common mutations identified and the number of specified unrelated patients in whom they were found. LQTS = long QT syndrome.

Overall, the majority of mutations (394 of 562, 70%) were missense, whereas 85 (15%) were frame-shift mutations, 33 (5.9%) involved splice sites, 33 (5.9%) were nonsense mutations, and 17 (3%) were in-frame insertions/deletions (Figure 3). Whereas 64% of all frame-shift mutations were identified in KCNH2 (representing 24% of all KCNH2 mutations), 76% of the splice-site mutations involved KCNQ1 (representing 12.5% of all KCNQ1 mutations). Surprisingly, as will be discussed below, 5 nonsense (Q73X, R179X, R222X, Y389X, and W1798X) and 2 frame-shift mutations (V850fs+18X and L1786fs+45X) were identified in SCN5A.

Figure 3.

Summary of mutation type for LQT1, LQT2, and LQT3. The distribution of mutation type (missense, frame shift, etc.) is summarized for the 3 major LQTS genes. LQTS = long QT syndrome.

For mutations in KCNQ1, 102 of 199 (51%) localized to the transmembrane spanning and pore-forming domains, 13 (6.5%) to the specialized subunit assembly region, 15 (7.5%) were in the N-terminus, and 69 (35%) resided in the C-terminus (Supplemental Table 1, Figure 4A). For mutations in KCNH2, 73 of 226 (32%) localized to the transmembrane spanning and pore-forming domains, 18 (8%) in the N-terminal PAS/PAC regulatory domains, 47 (21%) elsewhere in the N-terminus, 18 (8%) in the C-terminal cyclic nucleotide domain (cNBD), and 70 (31%) elsewhere in the C-terminus (Supplemental Table 2, Figure 4B). Among the 108 mutations in SCN5A, 11 (10%) localized to the N-terminus, 46 (43%) to the transmembrane spanning and pore-forming domains, 38 (35%) to the interdomain cytoplasmic linkers (DI–DII, DII–DIII, and DIII–DIV), and 13 (12%) to the C-terminus (Supplemental Table 3, Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Channel topology and location of putative LQTS-causing mutations for the 3 major LQTS genes. Missense mutations are indicated by white circles, whereas mutations other than missense (i.e., frame shift, deletions, splice-site, etc.) are depicted as gray circles. In addition, 3 different circle sizes are used, with the smallest circle indicating a mutation seen only once; a medium-sized circle for mutations observed in 2, 3, or 4 subjects; and the largest circle indicating those mutations observed at least 5 times. See Supplemental Tables 1–3 for details about each mutation depicted here. (A) Channel topology of Kv7.1’s pore-forming alpha subunit encoded by KCNQ1 and location of putative LQT1-causing mutations. (B) Channel topology of Kv11.1’s pore-forming alpha subunit encoded by KCNH2 and location of putative LQT2-causing mutations. (C) Channel topology of Nav1.5’s pore-forming alpha subunit encoded by SCN5A and location of putative LQT3-causing mutations. LQTS = long QT syndrome.

Discussion

Since clinical LQTS genetic testing became available in North America nearly 5 years ago, the yield of the genetic test has ranged between 33% and 39%. Previously, large-scale LQTS genetic testing for these 5 LQTS-causing channel genes (KCNQ1, KCNH2, SCN5A, KCNE1, and KCNE2) was limited to only a few research laboratories worldwide. In 2000, Splawski et al.30 performed mutational analysis of these 5 genes in a cohort of 262 patients with a high clinical probability for LQTS (average QTc of 492 ± 47 ms, 75% symptomatic) and identified putative LQTS-causing mutations in 177 subjects (68%). In a series of 541 LQTS referral patients, the yield of LQTS-associated mutations was 50% overall and ranged from a yield of 0% when the QTc was <400 ms to a high of 62% when the QTc was >480 ms.31

When considering a cumulative LQTS diagnostic Schwartz-Moss score, which is derived in part by the QTc, symptoms and family history, Tester et al.32 found that the yield of genetic testing for the 5 genes was nearly 75% among patients with the highest clinical probability for LQTS (Schwartz-Moss score ≥4). Napolitano et al.33 reported a 72% yield among their 430 unrelated clinically diagnosed LQTS patients referred for genetic testing. Among a series of unrelated patients all diagnosed with definite LQTS by a single LQTS specialist (M.J.A.), 75% had a positive LQTS genetic test.34 Together, these studies suggest that an ordering physician should expect that comprehensive open reading frame/splice site mutational analysis of these 5 LQTS-susceptibility genes should yield a possible LQTS-causing mutation about 75% of the time among their firmly diagnosed LQTS patients.

In addition, given several strong genotype–phenotype relationships such as swimming/LQT1, auditory triggers/LQT2, and postpartum/LQT2, targeted gene screening or phenotype-guided genetic testing may be possible.35 However, as shown in this study, nearly 10% of the mutation-positive subjects had multiple mutations, including 52 cases with mutations in >1 gene. Because their clinical/phenotypic information is unavailable, it is unknown whether their clinical profile would have predicted a complex genotype or whether such a targeted gene screen might have failed to elucidate their other mutation(s).

Here, the overall yield of 36% suggests that in clinical practice, prescribing physicians are submitting a spectrum of low-, intermediate-, and high-pretest-probability cases for genetic testing. However, the level of clinical suspicion for LQTS for each patient and the detailed reasons for submission by the referring physician are unknown. Previously, Tester et al.31,32 showed that among patients submitted for research-based genetic testing with an intermediate clinical probability, the yield was 44%. Further, among a series of unrelated patients evaluated by a single LQTS specialist (M.J.A.) and diagnosed with possible LQTS, the genetic test was positive in 38%.34 This LQTS genetic test’s 4.5-year yield (36%) suggests that appropriate clinical utilization has been taking place and continues, because the yield during the most recent year or past 500 cases was 39%. Moreover, the test was ordered by approximately 1,000 physicians, principally adult and pediatric heart rhythm specialists, other cardiologists, and geneticists in partnership with the patient’s cardiologist. The uniformity of yield between clinicians who have ordered only 1 test and those who have ordered many suggests an overall similar perspective among the users of this test.

It must also be kept in clear view that, as with most genetic tests, LQTS genetic test results are probabilistic rather than binary. The test identifies the presence of a probable/possible LQTS-causing mutation for which the probability for pathogenesis is influenced by many factors, including prior science, rarity, conservation, topological location, co-segregation, functional studies, and so forth. Before this compendium, >600 distinct mutations had been published by research laboratories as potential LQTS-causing mutations. However, fewer than 25% of these previously published mutations have been characterized by heterologous expression studies to demonstrate the anticipated loss-of-function (LQT1 and LQT2) or gain-of-function (LQT3) conferred by the mutation. Akin to virtually all other clinical genetic tests, no such functional assays are incorporated in this clinical LQTS genetic test.

Consequently, the ordering physician must be cognizant of the so-called background genetic noise rate for their particular disease-specific genetic test. In the case of LQTS, <3% of seemingly healthy Caucasians could have a seemingly positive LQTS genetic test. Previously, we showed that rare, missense (not nonsense, frame shift, or splice site) mutations with an allelic frequency ≤0.5% were detected in approximately 3% to 7% of now over 1,300 healthy volunteers, including <3% of Caucasians.15,16,29 Given the LQTS estimated incidence of 1 in 2,500, the vast majority of those variants must represent essentially innocuous, “just there, just rare, just along for the ride” genetic variants. Accordingly, this implies that for Caucasians, the false-positive genetic test rate associated with LQTS genetic testing is also <3%. If so, given the current utilization of the test with its average yield around 36%, then one would estimate that approximately 8% (3% divided by 36%) of the “positive” genetic test results represent, in fact, background variants rather than true pathogenic mutations that act as primary causes of LQTS.

Although background variants tend to localize to channel protein regions having more biological flexibility and putative mutations found in diagnosed LQTS patients tend to localize to more critical domains, like transmembrane spanning segments and the channel’s pore/selectivity filter, there is much overlap.15,16,29 Moreover, despite the passage of 14 years since the first LQTS-causative mutations were discovered, still one-third of the mutations being discovered today are novel. This new compendium of 562 distinct mutations, including 336 novel ones, should provide ample substrate for ongoing molecular/cellular structure–function studies to help improve our ability to quickly and accurately discern pathogenicity for novel mutations.

Study limitations

As a clinically available genetic test, access to the test was not restricted by any particular litmus test regarding the certainty of the clinical diagnosis of LQTS or conditioned upon receipt of any particular phenotypic data, such as a 12-lead ECG. Consequently, unlike the abundance of genotype–phenotype relationships that have been drawn from research laboratories over the past decade, this clinical compendium is unable to implicate any particular associations except for the age difference at genetic testing between male and female subjects and the suggestion that genotype-positive male subjects are slightly more likely to host multiple mutations than genotype-positive female subjects.

Furthermore, this compendium is expected to contain mutation-like background variants to a greater degree than other published compendia because of the lower pre-test probability of LQTS evidenced by the lower mutation yield relative to other published cohorts. Moreover, some of the mutations in this compendium may be associated with diseases aside from LQTS. For example, we surmise that the comprehensive genetic LQTS test, rather than the SCN5A only Brugada syndrome genetic test, may have been ordered for at least 7 patients with Brugada syndrome in whom either a nonsense or a frame shift mutation resulting in premature truncations of the sodium channel was identified. Intuitively, one would predict that such SCN5A mutations would result in a loss-of-function Brugada syndrome–like phenotype rather than a gain-of-function LQT3-like phenotype. 36 Despite these limitations, it is reasonable to estimate that the great majority of the mutations annotated in Supplemental Tables 1 through 5 are true LQTS-causing mutations, given the low background rate.29

Conclusion

Since its sentinel discovery as a channelopathy in 1995, the genomic understanding of LQTS has clearly matured and matriculated from bench to bedside, traversing the path from discovery to translation to clinical implementation. Now with its ready availability to clinicians, in contrast with the previous decade of research-based genetic testing, LQTS genetics/genomics must advance from mere implementation to more sophisticated interpretation in the hands of clinicians. This interpretative phase is where the majority of the >1,000 diseases for which genetic testing is available now reside, all facing the challenge of distinguishing pathogenic mutations from background genetic noise. The fulfillment of genomic, personalized, individualized medicine rests on our ability to succeed in doing just that.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

All mutational analyses performed in this study were conducted as part of clinical practice requested by the ordering physician. The authors thank the staff at PGxHealth, whose careful contributions to the laboratory work and analysis have made the study possible.

Supported by the Mayo Clinic Windland Smith Rice Comprehensive Sudden Cardiac Death Program (Dr. Ackerman), and the Leducq Foundation, Grant 05 CVD, Alliance against Sudden Cardiac death (Dr. Wilde). Dr. Ackerman is a consultant for PGxHealth. Intellectual property derived from Dr. Ackerman’s research program resulted in license agreements in 2004 between Mayo Clinic Health Solutions (formerly Mayo Medical Ventures) and PGxHealth (formerly Genaissance Pharmaceuticals).

Footnotes

Appendix

Supplementary data

The supplementary data includes Tables 1–5 which annotates the genetic information for each of the 562 distinct, putative LQTS-causative mutations reported herein. For example, the 199 possible LQT1-associated KCNQ1 mutations are provided in Supplemental Table 1.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.05.021.

References

- 1.Ackerman MJ. Cardiac channelopathies: it’s in the genes. Nat Med. 2004;10:463–464. doi: 10.1038/nm0504-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stramba-Badiale M, Crotti L, Goulene K, et al. Electrocardiographic and genetic screening for long QT syndrome: results from a prospective study on 44,596 neonates. Circulation. 2007;116 (abstract 1778)II_377. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Q, Curran ME, Splawski I, et al. Positional cloning of a novel potassium channel gene: KVLQT1 mutations cause cardiac arrhythmias. Nat Genet. 1996;12:17–23. doi: 10.1038/ng0196-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curran ME, Splawski I, Timothy KW, et al. A molecular basis for cardiac arrhythmia: HERG mutations cause long QT syndrome. Cell. 1995;80:795–803. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90358-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Q, Shen J, Splawski I, et al. SCN5A mutations associated with an inherited cardiac arrhythmia, long QT syndrome. Cell. 1995;80:805–811. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90359-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohler PJ, Schott J-J, Gramolini AO, et al. Ankyrin-B mutation causes type 4 long-QT cardiac arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death. Nature. 2003;421:634–639. doi: 10.1038/nature01335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Splawski I, Tristani-Firouzi M, Lehmann MH, Sanguinetti M, Keating M. Mutations in the hminK gene cause long QT syndrome and suppress IKs function. Nat Genet. 1997;17:338–340. doi: 10.1038/ng1197-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abbott GW, Sesti F, Splawski I, et al. MiRP1 forms IKr potassium channels with HERG and is associated with cardiac arrhythmia. Cell. 1999;97:175–187. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80728-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plaster NM, Tawil R, Tristani-Firouzi M, et al. Mutations in Kir2.1 cause the developmental and episodic electrical phenotypes of Andersen’s syndrome. Cell. 2001;105:511–519. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00342-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Splawski I, Timothy KW, Sharpe LM, et al. Cav1.2 calcium channel dysfunction causes a multisystem disorder including arrhythmia and autism. Cell. 2004;119:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vatta M, Ackerman MJ, Ye B, et al. Mutant caveolin-3 induces persistent late sodium current and is associated with long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 2006;114:2104–2112. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.635268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Medeiros-Domingo A, Kaku T, Tester DJ, et al. SCN4B-encoded sodium channel beta4 subunit in congenital long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 2007;116:134–142. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.659086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen L, Marquardt ML, Tester DJ, Sampson K, Ackerman MJ, Kass R. Mutation of an A-kinase-anchoring protein causes long-QT syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:20990–20995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710527105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ueda K, Valdivia C, Medeiros-Domingo A, et al. Syntrophin mutation associated with long QT syndrome through activation of the nNOS-SCN5A macromolecular complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9355–9360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801294105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ackerman MJ, Splawski I, Makielski JC, et al. Spectrum and prevalence of cardiac sodium channel variants among black, white, Asian, and Hispanic individuals: implications for arrhythmogenic susceptibility and Brugada/long QT syndrome genetic testing. Heart Rhythm. 2004;1:600–607. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2004.07.013. [see comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ackerman MJ, Tester DJ, Jones GS, Will M, Burrow C, Curran M. Ethnic differences in cardiac potassium channel variants: implications for genetic susceptibility to sudden cardiac death and genetic testing for congenital long QT syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:1479–1487. doi: 10.4065/78.12.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Association BCBS. [Accessed February 1, 2009];TEC report. Genetic testing for long QT syndrome. Assessment program. 2008 February;Volume 22(No. 9) Available at: http://www.bcbs.com/blueresources/tec/vols/22/22_09.html. [PubMed]

- 18.Tester DJ, Cronk LB, Carr JL, et al. Allelic dropout in long QT syndrome genetic testing: a possible mechanism underlying false-negative results. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:815–821. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.03.016. [see comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koopmann TT, Alders M, Jongbloed RJ, et al. Long QT syndrome caused by a large duplication in the KCNH2 (HERG) gene undetectable by current polymerase chain reaction-based exon-scanning methodologies. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:52–55. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.10.014. [see comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eddy C-A, MacCormick JM, Chung S-K, et al. Identification of large gene deletions and duplications in KCNQ1 and KCNH2 in patients with long QT syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:1275–1281. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antonarakis SE. Group AtNW. Recommendations for a nomenclature system for human gene mutations. Hum Mutat. 1998;11:1–3. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1998)11:1<1::AID-HUMU1>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray A, Donger C, Fenske C, et al. Splicing mutations in KCNQ1: a mutation hot spot at codon 344 that produces in frame transcripts. Circulation. 1999;100:1077–1084. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.10.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhuang Y, Weiner AM. A compensatory base change in U1 snRNA suppresses a 5′ splice site mutation. Cell. 1986;46:827–835. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90064-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogan PK, Svojanovsky S, Leeder JS. Information theory-based analysis of CYP2C19, CYP2D6 and CYP3A5 splicing mutations. Pharmacogenetics. 2003;13:207–218. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200304000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Q, Li Z, Shen J, Keating M. Genomic organization of the human SCN5A gene encoding the cardiac sodium channel. Genomics. 1996;34:9–16. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Splawski I, Shen J, Timothy K, Vincent GM, Lehmann M, Keating M. Genomic structure of three long QT syndrome genes: KVLQT1, HERG, and KCNE1. Genomics. 1998;51:86–97. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neyroud N, Richard P, Vignier N, et al. Genomic organization of the KCNQ1 K+ channel gene and identification of C-terminal mutations in the long-QT syndrome. Circ Res. 1999;84:290–297. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.3.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sebillon P, Beldjord C, Kaplan JC, Brody E, Marie J. A T to G mutation in the polypyrimidine tract of the second intron of the human beta-globin gene reduces in vitro splicing efficiency: evidence for an increased hnRNP C interaction. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3419–3425. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.17.3419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kapa S, Tester DJ, Salisbury BA, Wilde AA, Ackerman MJ. Distinguishing long QT syndrome-causing mutations from “background” genetic noise. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:S76. (abstr) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Splawski I, Shen J, Timothy KW, et al. Spectrum of mutations in long-QT syndrome genes. KVLQT1, HERG, SCN5A, KCNE1, and KCNE2. Circulation. 2000;102:1178–1185. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.10.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tester DJ, Will ML, Haglund CM, Ackerman MJ. Compendium of cardiac channel mutations in 541 consecutive unrelated patients referred for long QT syndrome genetic testing. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2:507–517. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tester DJ, Will ML, Haglund CM, Ackerman MJ. Effect of clinical phenotype on yield of long QT syndrome genetic testing. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:764–768. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Napolitano C, Priori SG, Schwartz PJ, et al. Genetic testing in the long QT syndrome: development and validation of an efficient approach to genotyping in clinical practice. JAMA. 2005;294:2975–2980. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.23.2975. [see comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taggart NW, Haglund CM, Tester DJ, Ackerman MJ. Diagnostic miscues in congenital long-QT syndrome. Circulation. 2007;115:2613–2620. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.661082. [see comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Langen IM, Birnie E, Alders M, Jongbloed RJ, Le Marec H, Wilde AA. The use of genotype-phenotype correlations in mutation analysis for the long QT syndrome. J Med Genet. 2003;40:141–145. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.2.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Antzelevitch C. Genetic basis of Brugada syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:756–457. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.03.015. [comment] erratum 2007;4:990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.