Abstract

Objectives

To determine if adolescents presenting to a Pediatric Emergency Department (PED) for an alcohol-related event requiring medical care differ in terms of substance use, behavioral and mental health problems, peer relationships, and parental monitoring, based on their history of marijuana use.

Methods

Cross-sectional comparison of adolescents 13–17 years old, with evidence of recent alcohol use, 13–17 years old, presenting to a PED based on a self-reported history of marijuana use. Assessment tools included the Adolescent Drinking Inventory, Adolescent Drinking Questionnaire, Young Adult Drinking and Driving Questionnaire, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, Behavioral Assessment System for Children, and Peer Substance Use and Tolerance of Substance Use Scale,

Results

Compared to alcohol only (AO) using adolescents, adolescents who use alcohol and marijuana (AM) have higher rates of smoking (F=23.62) and binge drinking (F=11.56), consume more drinks per sitting (F=9.03), have more externalizing behavior problems (F=12.53), and report both greater peer tolerance of substance use (F=12.99) and lower parental monitoring (F=7.12).

Conclusions

Adolescents who use both AM report greater substance use and more risk factors for substance abuse than AO using adolescents. Screening for a history of marijuana use may be important when treating adolescents presenting with an alcohol-related event. Alcohol and marijuana co-use may identify a high risk population, which may have important implications for ED clinicians in the ED care of these patients, providing parental guidance, and planning follow-up care.

Keywords: Alcohol, Marijuana, Adolescent, Emergency Department, Parenting, Peers

Introduction

Adolescents are among the highest users of alcohol and have some of the highest rates of problematic drinking[1]. In the Emergency Department (ED) setting, significant numbers of both injured[2–4] and non-injured[5] adolescents have been found to use alcohol. Despite recommendations by both the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma[6] and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine[7, 8] for alcohol screening and intervention among ED patients, ED physicians frequently fail to detect or refer patients for alcohol treatment[9, 10].

Several studies have identified screening tools that have shown promise for identifying alcohol using adolescents in the ED setting[11–13]. However, identification of alcohol using adolescents alone may not be sufficient. Pediatric Emergency Department (PED) intervention studies for such patients have found that while alcohol using adolescents may benefit from ED alcohol interventions, adolescents with a history of problematic alcohol use experience greater benefit[14, 15]. Screening for a history problematic adolescent alcohol and other drug use may thus be especially important in the ED setting.

Some research suggests that adolescent marijuana use may be an important “gateway” to other adolescent substance use, substance use disorders, and other psychosocial problems[16]. It is unclear whether asking adolescents about marijuana use is an effective screen for problematic substance use and/or other psychosocial problems.

Studies of older adolescents and young adults support the idea that alcohol and marijuana (AM) co-use portends worse outcomes than using alcohol only (AO). Stenbacka[17] examined alcohol and substance use in a large national register of Swedish men conscripted for military service at ages 18 and 19 years. At 27 year follow-up, the combination of problematic AM use in late adolescence was more strongly associated with adult alcohol abuse (Risk Ratio [RR]: 6.56) and substance abuse (RR: 19.37) than either problematic adolescent alcohol (RR: 3.21) or marijuana (RR: 2.04) use alone.

Flory et al[18] assessed a community sample of 481 older adolescents (19 to 21 years old) who had previously participated in a school-based (grades 6–10) drug use prevention program. The investigators estimated developmental trajectories of substance use based on early vs. late onset of alcohol and marijuana use. At adult re-assessment, AM using individuals were found to have more psychopathology, antisocial personality symptoms, total arrests, and alcohol and marijuana abuse/dependence than AO individuals.

Several studies have compared college students who used AO to those who used AM[19–21]. Together, these studies have found that AM using students experienced far more problems than AO using students, including hangovers, doing poorly in school, getting into arguments and physical altercations, driving while drunk, and riding with a drunk driver.

These studies consistently indicate that older adolescents who abuse both AM display greater impairment than AO using peers. It is unclear whether the same is true for younger adolescents and what additional factors might be related to AM use. To date, only one study investigating this question has included younger adolescents. Shillington and Clapp[22] used data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth and the Young Adult Survey to study adolescents ages 15–21 years. The authors found that adolescents using AM experienced more behavioral problems than their AO using peers.

Studies have also shown that parent and peer influences are strong predictors of adolescent substance use. For example, levels of parental contact and supervision[23, 24], parental norms against drinking[25], and number of deviant peers[26] are all known to affect an adolescent’s risk of substance use.

The purpose of this study was to assess whether differentiating AO vs. AM use among younger adolescents presenting to a PED is an effective way to identify teens with impaired functioning. These groups were compared regarding substance abuse and mental health history, as well as parenting and peer factors. It was hypothesized that AM using adolescents would have more impairment in all of these areas, i.e. substance abuse and psychosocial functioning, than AO using adolescents.

Methods

Baseline Recruitment

Adolescents, 13 to 17 years old, treated in a PED between May 2003 and November 2007 were eligible for this study if they had evidence of alcohol use prior to their PED visit. Patients were consecutively approached for enrollment during this time period. Adolescents who were suicidal, were in police custody, had serious injuries or illness requiring hospitalization, were not residing with a parent or guardian, non-English speaking were excluded from this study. Not all patients completed their baseline assessment and their data is not included here.

Study Setting and Population

The study site was a PED and an adjacent general emergency department (ED), both level 1 trauma centers serving a Southern New England catchment area.

Participants were asked about their race and if they considered themselves to be ethnically Hispanic or Latino. Because of the small number of responses in several racial categories and in order to be able to make statistically meaningful comparisons, participants were coded into two groups, “white” (non-Hispanic Caucasian) and “minority” (Hispanic or non-Caucasian). Annual household income was divided into 9 categories, ranging from less than $5,000 (1) to greater $150,000 (9).

Study Protocol and Design

Participants were recruited as part of a larger clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of a brief individual intervention compared to a brief individual intervention plus a family-based intervention. Alcohol positive adolescents were referred to the study by the PED or biochemistry lab staff. Research staff were sent an electronic page when an adolescent was identified in the PED either as having consumed any alcohol within six hours of their admission (PED staff) or as having tested positive (i.e. blood alcohol content (BAC) > 0.0 gm/ml) for alcohol via a medical staff-drawn blood test (PED or biochemistry lab staff). Participants were divided into AO and AM co-use categories based on a subject’s self-reported marijuana use. In order to be considered a MJ user, participants answered yes to the question, “Have you ever used marijuana?”

The data reported here were collected as part of the baseline adolescent and parent assessments. Baseline assessments for both the adolescents and their parents were completed prior to the randomization to the interventions being tested in the larger clinical trial. All participants were required to pass a brief mental status exam before completing the baseline assessments. Parental consent and adolescent assent were obtained for all the adolescents in the study. The consent/assent procedure included assurances that the parents would not be informed of any of the teen’s responses. No adolescent was approached until their BAC was below 0.1 gm/ml and/or they could pass a mental status exam. All procedures were approved by the overseeing university and hospital Institutional Review Boards. If patients were unable to complete their participation during their PED visit, they were scheduled to return to the hospital within a few days.

Measures

The assessment measures were read aloud to adolescents and self-administered by parents. The assessment battery took approximately 45 minutes to complete.

Substance use and related behaviors

The Adolescent Drinking Inventory (ADI)[27] is a 24-item self-report measure which focuses on social, psychological, and physical symptoms of alcohol problems. The Adolescent Drinking Questionnaire (ADQ)[28] assesses recent drinking frequency, quantity, frequency of high-volume drinking, frequency of intoxication over the prior 3 months, and maximum number of drinks consumed on any one occasion. Two items from the Young Adult Drinking and Driving Questionnaire[29] were asked, the frequency of driving after engaging in any drinking at all and riding with an intoxicated driver.

Teen mood and behavioral problems

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CESD)[30, 31] measures depressive symptomatology. The Behavioral Assessment System for Children (BASC)[32] Parent Rating Scale evaluates adaptive and problem behaviors in adolescents ages 14–18 years in community and home settings. The adolescent’s parents completed a BASC.

Peer factors

Peer Substance Use and Tolerance of Substance Use[33] scale consists of items in which adolescents estimate how many of their friends use alcohol, marijuana, and other drugs. The scale also assesses what the adolescents think their close friends would feel about their using marijuana, alcohol and other drugs. Child-Parent Peer Ratings and Social Skills Inventories[34] assess interactions with prosocial and deviant peers. Separate scores were derived for parents and adolescents.

Parenting factors

Parental monitoring was examined using two scales. Four questions from the Strictness/Supervision Scale[35, 36] (SSS) asked both parents and adolescents to what extent the parent knew where the adolescent went at night, how the adolescent spent his or her time, where the adolescent went after school, and who the adolescent's friends were. Each item was rated on a 4-point scale. Adolescents and parents also completed the Family Management subscale from the Parent/Student Self-Check[34] (PSC/SSC), which assesses parental family management including parental monitoring. Adolescents completed the 14 item scale regarding the parental figure of their choosing (e.g. mother, father).

Data Analysis

All dependent variables were first checked for distributional assumptions. Several had skewed distributions and were log-transformed prior to analysis. To assist in clinically intuitive interpretation of results, non-log transformed data is presented in the tables. Bivariate analyses were performed to determine whether there were any demographic differences between the two groups. The two groups were compared for equivalency of baseline variables using t-tests and Fisher’s exact test. A series of 2 × 2 analysis of variance (ANOVA) were performed on all outcome variables, to control for a significant difference among groups by race. To adjust for multiple comparisons, a Bonferroni correction was calculated. Cronbach alphas, a measure of internal consistency, were calculated for psychometric measures. Values of 0.70 or greater are generally accepted as demonstrating adequate internal consistency. All statistical calculations were performed using SPSS software (version 15.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

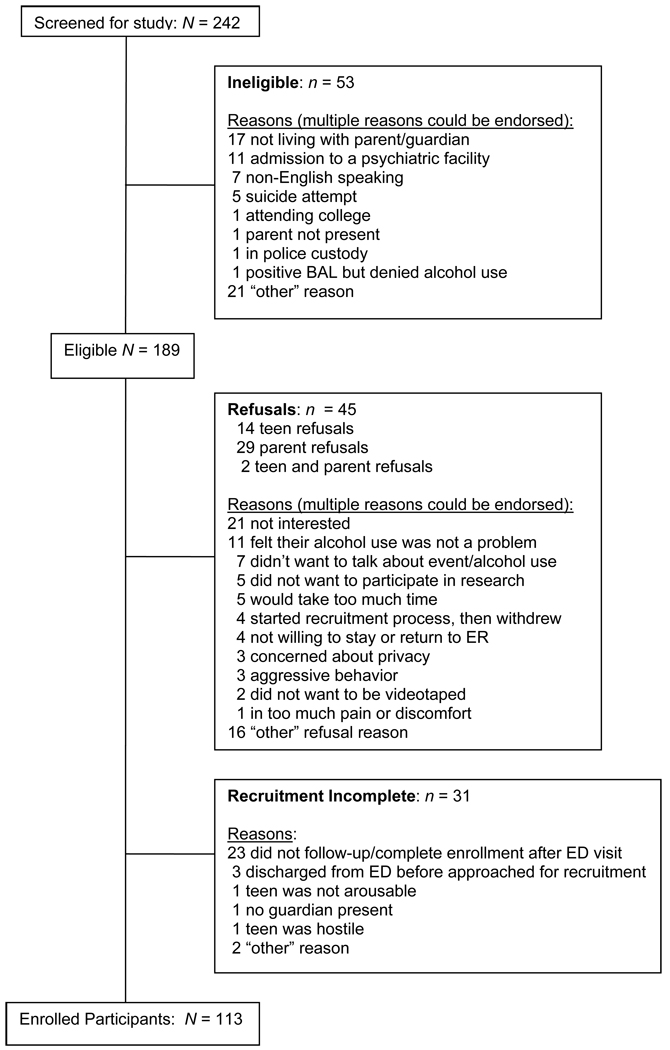

A total of 242 patients were screened for this study (figure 1). Fifty three (21%) were ineligible for the study. An additional 31 patients did not complete the recruitment process (13%). Of the remaining 158 eligible patients, 45 declined to participate. The most commonly cited refusal reasons were lack of interest in the study, they did not believe that their alcohol use was a problem, and/or they did not want to talk about their alcohol use. Recruited and non-recruited patients were not significantly different in age (15.3 vs. 15.6 years, respectively) or gender (45% vs. 49% male gender, respectively). They did differ on reason for ED visit; recruited patients were more likely to have presented for alcohol intoxication only, while non-recruited patients were more likely to have presented with the combination of alcohol use and an injury or an “other” reason (χ2=7.12, df=2, p=0.03).

Figure 1.

The study sample consisted of 113 patients, 51 (45.1%) boys and 62 (54.9%) girls with a mean age of 15.3 years (SD =1.2). The majority of participants (n=108, 96%) were recruited from the PED; the other 5 subjects were recruited from the general ED. Participants identified themselves as African American (1.8%), Asian (2.7%), Caucasian (67.3%), Hispanic (26.5%), and more than one race (1.8%). Participants presented to the PED for the following reasons: 96 (85% of sample) for alcohol intoxication only, 6 (5.3%) with intoxication in conjunction with a motor vehicle crash, 2 (1.8%) each for lacerations, assault related injuries, falls, and being ill, and 1 (0.9%) each for a sports related injury, non-suicidal psychiatric condition, and an unclassified event. Twelve percent of patients completed their baseline assessment in the ED, 70% on a visit to the study’s office, 13% on a home visit, and 5% in another location.

Fifty seven percent (64/113) of subjects reported using AO; 43% (49/113) reported using both AM. Adolescents who used both AM were not significantly different from those who used AO on age (15.4 vs. 15.3 years, respectively), gender (53% vs. 39% male gender), or income class (5.6 vs. 6.1). Subjects did differ on race, however. In the AM group, 77% were White, where 59% of the AO group was White (χ2=4.16,df=1, p=0.04).

Cronbach alphas in this study were: CESD, 0.90; Peer Substance Use and Tolerance of Substance Use, 0.79 (peer substance use) and 0.91 (peer tolerance of substance use); Child-Parent Peer Ratings and Social Skills Inventories, 0.82 and .86. (parent ratings of prosocial peers and deviant peers, respectively), and 0.67 and 0.55 (adolescent ratings of prosocial peers and deviant peers, respectively); Strictness/Supervision Scale, 0.66 (adolescent scale) and 0.88 (parent scale); Student Self-Check, 0.91; and Parent Self-Check, 0.88.

Table I presents a comparison of other substance use variables by group. Compared to AO participants, AM participants smoked more cigarettes per day, had more days of binge drinking (more than 5 drinks in one sitting), and consumed a greater number of drinks per drinking occasion over the prior 3 months. There was also a trend (p<0.05) among AM teens to consume a higher maximum number of drinks at one sitting over the prior 3 months, have higher BAC’s when calculated at the time of their PED visit, to have ridden with an impaired driver, and to have higher ADI scores, compared to AO adolescents. Additional analyses (data not shown in table) revealed that among AM using adolescents, 87.2% smoked cigarettes, compared to only 20.3% of AO adolescents (χ2=46.56, df=1, p=0.000).

Table I.

Differences in Substance Use Variables by Alcohol–Marijuana and Alcohol-only Groups, and Race

| Alcohol Use Only | Alcohol – MJ Use | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substance Use and Related Variables |

Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | N | F |

| Cigarettes per day | |||||

| White | 0.24 (1.09) | 37 | 6.82 (8.69) | 38 | 23.62 (by MJ)* |

| Minority | 0.54 (2.08) | 26 | 1.55 (3.59) | 11 | 6.56 (by race) t |

| Total | 0.37 (1.57) | 63 | 5.63 (8.11) | 49 | 8.61 interaction)* |

| Days drinking per month | |||||

| White | 1.92 (2.65) | 38 | 4.26 (5.07) | 38 | 2.58 (by MJ) |

| Minority | 1.87 (4.15) | 26 | 1.64 (2.84) | 11 | 5.57 (by race) t |

| Total | 1.90 (3.31) | 64 | 3.67 (4.77) | 49 | 2.34 (interaction) |

| Days binge drinking per month | |||||

| White | 0.45 (0.28) | 38 | 2.90 (5.24) | 38 | 11.56 (by MJ)* |

| Minority | 1.15 (3.85) | 26 | 1.05 (1.15) | 11 | 1.32 (by race) |

| Total | 0.73 (2.46) | 64 | 2.48 (4.70) | 49 | 3.14 (interaction) |

| Number of drinks per sitting/last 3 months | |||||

| White | 4.92 (1.72) | 38 | 5.74 (1.64) | 38 | 9.03 (by MJ)* |

| Minority | 4.65 (1.74) | 26 | 6.00 (1.61) | 11 | 0.00 (by race) |

| Total | 4.81 (1.72) | 64 | 5.80 (1.62) | 49 | 0.54 (interaction) |

| Maximum number of drinks/last 3 months | |||||

| White | 7.90 (4.68) | 38 | 11.68 (6.18) | 38 | 4.83 (by MJ) t |

| Minority | 8.23 (6.54) | 26 | 9.64 (2.25) | 11 | 0.52 (by race) |

| Total | 8.03 (5.47) | 64 | 11.22 (5.59) | 49 | 1.02 (interaction) |

| Calculated BAC in PED | |||||

| White | 0.24 (.10) | 38 | 0.26 (.09) | 38 | 6.76 (by MJ) t |

| Minority | 0.21 (.09) | 26 | 0.29 (.08) | 11 | 0.06 (by race) |

| Total | 0.23 (.10) | 64 | 0.27 (.09) | 49 | 1.97 (interaction) |

| Number of times rode with impaired driver | |||||

| White | 0.63 (1.82) | 38 | 3.95 (7.80) | 38 | 6.18 (by MJ) t |

| Minority | 1.19 (2.99) | 26 | 1.18 (1.40) | 11 | 0.18 (by race) |

| Total | 0.86 (2.36) | 64 | 3.33 (6.97) | 49 | 2.51 (interaction) |

| Adolescent Drinking Inventory | |||||

| White | 10.79 (6.58) | 38 | 18.42 (11.82) | 38 | 4.65 (by MJ) t |

| Minority | 11.58 (8.97) | 26 | 12.55 (8.58) | 11 | 1.63 (by race) |

| Total | 11.11 (7.58) | 64 | 17.10 (11.40) | 49 | 2.79 (interaction) |

p < 0.006 (Bonferroni correction)

p < 0.05 (trend towards significance)

Regarding other illicit substance use, eleven of the 49 (22%) AM subjects reported such use, compared to one of the 64 (2%) AO subjects. Three AM subjects also used stimulants, two admitted to “designer drug” use, and one each endorsed cocaine, opiate, and “other medication” use. Three AM subjects used multiple other substances, including designer drugs, stimulants, sedatives, cough medicines, and hallucinogens. The lone AO subject reported “other medicine” use.

Table II examines depressed mood and behavior variables by group. Parents of AM teens reported their teens had significantly more externalizing problem behaviors than parents of AO teens. There was a trend for AM teens to report higher depression (CESD) scores than AO teens. Additionally, there was a trend for parents of AM teens to report their teens having more internalizing problem behaviors.

Table II.

Alcohol–Marijuana and Alcohol-only Groups, by race, and Adolescent Variables

| Alcohol Use Only | Alcohol – MJ Use | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mood and Behavior Variables |

Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | N | F |

| CESD | |||||

| White | 8.92 (7.24) | 38 | 15.26 (12.10) | 38 | 4.29 (by MJ) t |

| Minority | 10.69 (10.15) | 26 | 13.09 (8.63) | 11 | 0.01 (by race) |

| Total | 9.64 (8.51) | 64 | 14.78 (11.36) | 49 | 0.87 (interaction) |

| Externalizing Behaviors (BASC) | |||||

| White | 56.73 (13.46) | 37 | 66.64 (17.13) | 36 | 12.53 (by MJ)* |

| Minority | 53.04 (13.42) | 24 | 66.91 (20.27) | 11 | 0.26 (by race) |

| Total | 55.28 (13.46) | 61 | 66.70 (17.68) | 47 | 0.35 (interaction) |

| Internalizing Behaviors (BASC) | |||||

| White | 50.62 (9.62) | 37 | 55.44 (12.86) | 36 | 4.03 (by MJ) t |

| Minority | 49.54 (8.55) | 24 | 54.82 (18.03) | 11 | 0.11 (by race) |

| Total | 50.20 (9.16) | 61 | 55.30 (14.02) | 47 | 0.01 (interaction) |

p < 0.017 (Bonferroni correction)

p < 0.05 (trend towards significance)

BASC: Behavioral Assessment System for Children

CESD: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

Analysis of peer variables by group is presented in Table III. Adolescents who used AM reported greater peer tolerance of substance use than AO adolescents. There was a trend for AM adolescents to report more peer substance use, more deviant peers (both teen and parent report) and fewer pro-social peers (teen report only) as compared to AO teens.

Table III.

Alcohol–Marijuana and Alcohol-only Groups, by race, and Peer Variables

| Alcohol Use Only | Alcohol – MJ Use | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer Variables | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | N | F |

| Peer Substance Use | |||||

| White | 0.86 (.75) | 38 | 1.59 (.84) | 38 | 6.63 (by MJ) t |

| Minority | 0.88 (.86) | 26 | 1.03 (.75) | 11 | 2.42 (by race) |

| Total | 0.86 (.79) | 64 | 1.46 (.84) | 49 | 2.85 (interaction) |

| Peer Tolerance of Substance Use | |||||

| White | 2.10 (.67) | 38 | 2.54 (.69) | 38 | 12.99 (by MJ)* |

| Minority | 1.84 (.88) | 26 | 2.57 (1.01) | 11 | 0.50 (by race) |

| Total | 2.00 (.76) | 64 | 2.55 (.76) | 49 | 0.80 (interaction) |

| Deviant Peers (Teen report) | |||||

| White | 1.81 (.59) | 38 | 2.66 (.90) | 38 | 5.40 (by MJ) t |

| Minority | 2.25 (.85) | 26 | 2.16 (.66) | 11 | 0.04 (by race) |

| Total | 1.99 (.73) | 64 | 2.55 (.87) | 49 | 8.28 (interaction)* |

| Prosocial Peers (Teen report) | |||||

| White | 3.67 (.67) | 38 | 3.08 (.65) | 38 | 4.41 (by MJ) t |

| Minority | 3.39 (.79) | 26 | 3.36 (.55) | 11 | 0.00 (by race) |

| Total | 3.55 (.73) | 64 | 3.14 (.64) | 49 | 3.82 (interaction) |

| Deviant Peers (Parent report) | |||||

| White | 1.64 (.72) | 37 | 2.51 (.97) | 37 | 8.60 (by MJ)* |

| Minority | 2.10 (1.13) | 23 | 2.46 (1.22) | 11 | 0.91 (by race) |

| Total | 1.82 (.92) | 60 | 2.47 (1.01) | 48 | 1.53 (interaction) |

| Prosocial Peers (Parent report) | |||||

| White | 3.68 (.89) | 37 | 2.85 (.88) | 37 | 1.56 (by MJ) |

| Minority | 2.75 (1.14) | 24 | 3.05 (1.19) | 11 | 2.99 (by race) |

| Total | 3.31 (1.09) | 61 | 2.91 (.95) | 48 | 7.00 (interaction) t |

p < 0.008 (Bonferroni correction)

p < 0.05 (trend towards significance)

Table IV presents a comparison of parental monitoring variables by group. On the Strictness/Supervision scale, parents of AM teens reported less parental monitoring than parents of AO teens. On the Family Management scale of the SSC, AM teens reported less parental monitoring by their primary caregiver than AO teens. There was also a trend among AM using teens to report less parental monitoring on the SSS than AO teens.

Table IV.

Alcohol–Marijuana and Alcohol-only Groups, by race, and Parental Monitoring Variables

| Alcohol Use Only | Alcohol – MJ Use | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parenting Variables | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | N | F |

| Strictness/Supervision Scale (teen) | |||||

| White | 3.34 (.54) | 38 | 2.94 (.55) | 38 | 4.17 (by MJ) t |

| Minority | 3.14 (.53) | 26 | 3.07 (.61) | 11 | 0.09 (by race) |

| Total | 3.26 (.54) | 64 | 2.97 (.56) | 49 | 1.93 (interaction) |

| Strictness/Supervision Scale (parent) | |||||

| White | 3.49 (.45) | 37 | 3.10 (.64) | 37 | 7.12 (by MJ)* |

| Minority | 3.02 (.76) | 24 | 2.66 (.98) | 11 | 10.49 (by race)* |

| Total | 3.31 (.63) | 61 | 3.00 (.74) | 48 | 0.01 (interaction) |

| Family Management Scale (PSC) | |||||

| White | 7.15 (1.53) | 33 | 5.90 (1.73) | 32 | 5.41 (by MJ) t |

| Minority | 6.96 (1.98) | 19 | 6.17 (2.53) | 8 | 0.01 (by race) |

| Total | 7.08 (1.69) | 52 | 5.95 (1.88) | 40 | 0.27 (interaction) |

| Family Management Scale (SSC) | |||||

| White | 7.67 (1.74) | 38 | 6.80 (1.39) | 38 | 7.44 (by MJ)* |

| Minority | 7.32 (1.87) | 25 | 6.25 (1.80) | 11 | 1.57 (by race) |

| Total | 7.53 (1.79) | 63 | 6.67 (1.49) | 49 | 0.08 (interaction) |

p < 0.013 (Bonferroni correction)

p < 0.05 (trend towards significance)

PSC: Parent Self Check

SSC: Student Self Check

Because the two groups differed by race, 2 (AO vs. AM) × 2 (White vs. minority) ANOVA’s were conducted, using all outcome variables. A main effect of race was observed on the parent report of parental monitoring on the SSS [F(1,88)=5.41, p=0.022], with minority parents reporting significantly less monitoring of their teens than white parents. There was a significant race × marijuana status interaction for cigarette smoking [F(1,108)=8.61, p=0.004] and deviant peers [F(1,109)=8.28, p=0.005].

To elucidate the effect of each factor on the other factors, simple effects analyses examining the unique effects of one factor at the each level of the other factor were performed. Simple effects analysis of cigarette smoking revealed that white AM adolescents smoked significantly more cigarettes per day than minority AM teens [F(1,108)=11.77, p=0.001]. Among the AO teens, there was no significant difference by race. Simple effects analysis of deviant peers revealed that minority AO teens associated with more deviant peers than white AO adolescents [F(1,109)=5.05, p=0.027]. Among AM teens, there was no significant difference by race.

Discussion

This study’s findings are consistent with that of other studies of older adolescents and college students[18–21], which found that older adolescents and young adults who used both AM reported more psychosocial, family, and peer risk factors than those that use AO[17]. In this study, younger adolescents who use both AM have a significantly greater likelihood of increased alcohol and tobacco use compared to AO using teens. Additionally, these adolescents were more likely to report poorer parental supervision and a greater number of deviant peers.

The findings of this study have important ramifications for ED clinicians who care for adolescents who present to the ED with an alcohol-related event. A positive response to questions about both alcohol and marijuana use should alert the clinician that their patient may be at higher risk for a number of untoward outcomes than if only alcohol use is endorsed. In particular, it is likely that an AM using patient will be a heavier drinker and cigarette smoker than AO using patients. The clinician should probe as needed for other risky behaviors. The ability to rapidly screen for high risk patients will help ED clinicians utilize their time and resources more efficiently and efficaciously.

Spirito et al.[15] found that adolescents with problematic drinking had a greater response to ED alcohol interventions than adolescents without problematic drinking. More intensive interventions, especially those which increase parental involvement with and monitoring of their teen, may be necessary for successful intervention with adolescents using both AM[37]. Identifying high risk adolescent drinkers is thus important not only in terms of post-ED visit follow-up care, but may also help determine which ED patients are mostly likely to benefit from ED interventions.

Brief screening tools are particularly appealing to ED clinicians, given the busy, hectic nature of the ED clinical environment. Single screening question tools have been shown to successfully identify alcohol using college students at high risk for alcohol related injury[38] and alcohol misuse among primary care patients[39]. A two item depression screening tool has also been validated in a PED population[40]. Given the burgeoning emphasis on SBIRT (Screen, Brief Intervention, Refer to Treatment) by the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine[7], the American College of Surgeons[6], and other professional medical organizations, effective screening methods are a growing need. A single question about marijuana use, asked of alcohol positive ED adolescent patients, may be an important way for ED clinicians to identify particularly high risk adolescents with problematic alcohol use. The 2007 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance survey found a 38.1% lifetime prevalence of marijuana use by adolescents in the United States[41]. This high prevalence of marijuana use in national surveys and in this study lends plausibility to the idea that asking about its’ use may be a high yield screening question.

The results of this study differ from that of Shillington and Clapp[22], the only other study which included younger adolescents. While both studies found higher rates of psychosocial problems in AM using adolescents, the previous study found no difference in drinking problems after controlling for demographic variables, co-morbid AM use, other substance use variables, and psychological factors (religiosity and impulsivity). In contrast, this study found greater tobacco and alcohol use among AM using teens. A possible explanation for the observed differences between the 2 studies includes the method used to identify marijuana use, the settings, and differences in the psychosocial variables included in the analyses. Another difference between the 2 studies is the age of the study populations. In this study, participants were younger (mean age: 15.4 years) than in the previous study (mean age: 17.1 years). It is known that adolescent substance use patterns vary significantly by age[42–44]. Marijuana use among 18–20 year old adolescents is 3–4 times that of 12–14 year old adolescents[42, 43]. It is possible that adolescents who use marijuana at an earlier age have worse substance use outcomes.

The fact that adolescents in this study are younger than those in the previous studies but had similar patterns of problems as studies with older subjects supports the idea that problematic young adult substance abuse often begins in adolescence. For example, using data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, Muthén and Muthén[45] found that the strongest predictor of heavy drinking at age 18 was early onset of drinking. Hingson and Zha[46] examined data from the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions, and found that earlier age of onset drinking significantly increased the likelihood of adult alcohol use disorders and alcohol related problems. Early detection and intervention for substance use in adolescence may thus be important in forestalling the development of adult substance abuse.

There are several limitations of this study. The ethnic and racial characteristics of this sample were such that subjects had to be grouped into two categories (white vs. minority), which affects the interpretability of this study. Additional research is needed to examine racial differences among AO and AM using adolescents. Because of the cross-sectional nature of this data, the precise relationship between marijuana use and the observed associations cannot be determined. It is also possible that those adolescents who participated in this study are different than those that declined to participate or did not complete their baseline assessment battery, which may also limit the generalizability of this study’s findings. Another limitation is that all the study measures rely on adolescent or parent self-report. It is possible that the responses were not accurate or that the participants provided socially desirable answers. However, if this occurred, it is likely that this study’s results underestimate the true association. Another possibility is that how truthfully patients answered the questions may have been influenced by having been recruited in the PED. The adolescent may have feared repercussions if they admitted to use. However, most of the baseline assessments occurred after discharge from the PED, which may have limited this potential problem.

There are numerous areas for future research, which would further the understanding of how AM co-use contributes to substance related and psychosocial problems. Previous studies[20, 21] have found significantly higher rates of substance related violence and problems with the legal and law-enforcement systems among adults who use AM than those that use AO. This relationship remained robust even after controlling for potential confounders. It is unclear if this association is true for younger adolescents as well. Another important, unanswered question is whether the apparently worse clinical condition of AM (compared to AO) using younger adolescents is causally due to marijuana use. Is marijuana truly the “gateway” to other substances and psychosocial problems? Or is marijuana use an important marker of persons at high risk for substance and/or psychosocial problems? For example, the relationship between marijuana and tobacco use, as seen in this and other studies[47], is well known. What is less clear is the causal (if at all) nature of the relationship. Understanding these relationships are critical to successfully designing and implementing effective screening, treatment and prevention programs. Finally, prospective validation of co-morbid AM use as a screen for problematic alcohol use and poor psychosocial functioning is needed.

Acknowledgments

Funding Support: NIAAA Grant# AA014934

Contributor Information

Thomas H. Chun, Departments of Emergency Medicine and Pediatrics, The Alpert Medical School of Brown University.

Anthony Spirito, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies, The Alpert Medical School of Brown University.

Lynn Hernández, Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies, The Alpert Medical School of Brown University.

Anne M. Fairlie, Department of Psychology, University of Rhode Island.

Holly Sindelar-Manning, The Child Neurodevelopment Center, Rhode Island Hospital.

Cheryl A. Eaton, Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies, Brown University.

William Lewander, Departments of Emergency Medicine and Pediatrics, The Alpert Medical School of Brown University.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Tenth Special Report to the U.S. Congress on Alcohol and Health. 2000

- 2.Bates BA, Shannon MW, Woolf AD. Ethanol-related visits by adolescents to a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1995;11(2):89–92. doi: 10.1097/00006565-199504000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maio RF, et al. Injury type, injury severity, and repeat occurrence of alcohol-related trauma in adolescents. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1994;18(2):261–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mannenbach MS, Hargarten SW, Phelan MB. Alcohol use among injured patients aged 12 to 18 years. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4(1):40–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1997.tb03641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnett NP, et al. Detection of alcohol use in adolescent patients in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5(6):607–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1998.tb02469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American College of Surgeons, Committee on Trauma. Resources for the Optimal Care of Injured Patients: 2006. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Babcock Irvin C, Wyer PC, Gerson LW. Preventive care in the emergency department, Part II: Clinical preventive services--an emergency medicine evidence-based review. Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Public Health and Education Task Force Preventive Services Work Group. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(9):1042–1054. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb02098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rhodes KV, Gordon JA, Lowe RA. Preventive care in the emergency department, Part I: Clinical preventive services--are they relevant to emergency medicine? Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Public Health and Education Task Force Preventive Services Work Group. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(9):1036–1041. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb02097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Becker B, et al. Alcohol use among subcritically injured emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 1995;2(9):784–790. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1995.tb03272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D'Onofrio G, et al. Patients with alcohol problems in the emergency department, part 1: improving detection. SAEM Substance Abuse Task Force. Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5(12):1200–1209. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1998.tb02696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung T, et al. Screening adolescents for problem drinking: performance of brief screens against DSM-IV alcohol diagnoses. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61(4):579–587. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelly TM, et al. Alcohol use disorders among emergency department-treated older adolescents: a new brief screen (RUFT-Cut) using the AUDIT, CAGE, CRAFFT, and RAPS-QF. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28(5):746–753. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000125346.37075.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelly TM, et al. A comparison of alcohol screening instruments among under-aged drinkers treated in emergency departments. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37(5):444–450. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/37.5.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monti PM, et al. Brief intervention for harm reduction with alcohol-positive older adolescents in a hospital emergency department. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67(6):989–994. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spirito A, et al. A randomized clinical trial of a brief motivational intervention for alcohol-positive adolescents treated in an emergency department. J Pediatr. 2004;145(3):396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Cannabis use and other illicit drug use: testing the cannabis gateway hypothesis. Addiction. 2006;101(4):556–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stenbacka M. Problematic alcohol and cannabis use in adolescence--risk of serious adult substance abuse? Drug Alcohol Rev. 2003;22(3):277–286. doi: 10.1080/0959523031000154418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flory K, et al. Early adolescent through young adult alcohol and marijuana use trajectories: early predictors, young adult outcomes, and predictive utility. Dev Psychopathol. 2004;16(1):193–213. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shillington AM, Clapp JD. Substance use problems reported by college students: combined marijuana and alcohol use versus alcohol-only use. Subst Use Misuse. 2001;36(5):663–672. doi: 10.1081/ja-100103566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shillington AM, Clapp JD. Heavy alcohol use compared to alcohol and marijuana use: do college students experience a difference in substance use problems? J Drug Educ. 2006;36(1):91–103. doi: 10.2190/8PRJ-P8AJ-MXU3-H1MW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rhodes WA, et al. Substance use problems reported by historically Black college students: combined marijuana and alcohol use versus alcohol alone. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2008;40(2):201–205. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2008.10400631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shillington AM, Clapp JD. Beer and bongs: differential problems experienced by older adolescents using alcohol only compared to combined alcohol and marijuana use. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2002;28(2):379–397. doi: 10.1081/ada-120002980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mulhall PF, Stone D, Stone B. Home alone: is it a risk factor for middle school youth and drug use? J Drug Educ. 1996;26(1):39–48. doi: 10.2190/HJB5-0X30-0RH5-764A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Windle MT. Alcohol use among adolescents. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1999. 126 pp. x. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kosterman R, et al. The dynamics of alcohol and marijuana initiation: patterns and predictors of first use in adolescence. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(3):360–366. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.3.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Curran PJ, Stice E, Chassin L. The relation between adolescent alcohol use and peer alcohol use: a longitudinal random coefficients model. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65(1):130–140. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrell AV, Wirtz PW. Screening for adolescent problem drinking: Validation of a multidimensional instrument for case identification. Psychological Assessment. 1989;1(1):61–63. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jessor R, Chase JA, Donovan JE. Psychosocial correlates of marijuana use and problem drinking in a national sample of adolescents. Am J Public Health. 1980;70(6):604–613. doi: 10.2105/ajph.70.6.604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donovan JE. Young adult drinking-driving: behavioral and psychosocial correlates. J Stud Alcohol. 1993;54(5):600–613. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Radloff L. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Radloff L. The Use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in Adolescents and Young Adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1991;20:149–166. doi: 10.1007/BF01537606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reynolds C, Kamphaus R. The Clinician’s Guide to the Behavior Assessment System for Children (BASC) New York: Guilford; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chassin L, Rogosch F, Barrera M. Substance use and symptomatology among adolescent children of alcoholics. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100(4):449–463. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dishion T, Kavanaugh K. Intervening in Adolescent Problem Behaviors. A Family Centered Approach. New York: Guilford; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Forehand R, et al. Role of parenting in adolescent deviant behavior: replication across and within two ethnic groups. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65(6):1036–1041. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.6.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steinberg L, et al. Impact of parenting practices on adolescent achievement: authoritative parenting, school involvement, and encouragement to succeed. Child Dev. 1992;63(5):1266–1281. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson PB, Johnson HL. Reaffirming the power of parental influence on adolescent smoking and drinking decisions. Adolescent & Family Health. 2001;2(1):37–43. [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Brien MC, et al. Single question about drunkenness to detect college students at risk for injury. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(6):629–636. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seale JP, et al. Primary care validation of a single screening question for drinkers. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67(5):778–784. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rutman MS, Shenassa E, Becker BM. Brief screening for adolescent depressive symptoms in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15(1):17–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2007.00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eaton DK, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance--United States, 2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2008;57(4):1–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Institute of Drug Abuse. [cited 2008 September 1, 2008];NIDA InfoFacts: High School and Youth Trends. 2007 Available from: http://www.nida.nih.gov/Infofacts/HSYouthtrends.html.

- 43.Brasseux C, et al. The changing pattern of substance abuse in urban adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152(3):234–237. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.3.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gilvarry E. Substance abuse in young people. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41(1):55–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Muthen BO, Muthen LK. The development of heavy drinking and alcohol-related problems from ages 18 to 37 in a U.S. national sample. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61(2):290–300. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hingson RW, Zha W. Age of drinking onset, alcohol use disorders, frequent heavy drinking, and unintentionally injuring oneself and others after drinking. Pediatrics. 2009;123(6):1477–1484. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ellickson PL, et al. Antecedents and outcomes of marijuana use initiation during adolescence. Prev Med. 2004;39(5):976–984. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]