Abstract

An improved method for direct oxidative coupling of o-xylene could provide streamlined access to an important monomer used in polyimide resins. The use of 2-fluoropyridine as a ligand has been found to enable unprecedented levels of chemo- and regioselectivity in this Pd-catalyzed aerobic oxidative coupling reaction. Preliminary insights have been obtained into the origin of the effectiveness of 2-fluoropyridine as a ligand.

Keywords: C-H activation, palladium, oxidation, oxidative coupling, aerobic oxidation, industrial chemistry

The synthesis of biaryls via direct oxidative coupling of arenes [Eq. (1)] is a prominent contemporary challenge in organic chemistry, and significant recent efforts have been directed toward homocoupling[1] and cross-coupling[2]

| (1) |

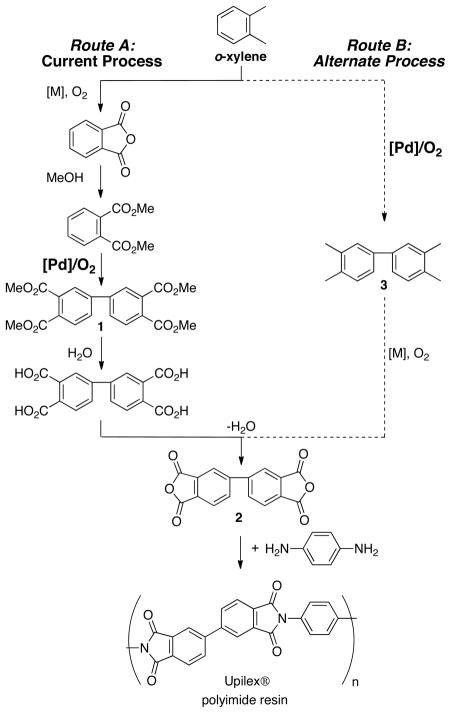

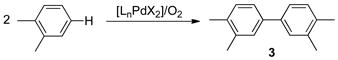

methods. Reactions of this type first emerged in the mid-1960s, when the oxidative homocoupling of simple arenes was reported by van Helden and Verberg using stoichiometric PdII salts, [3] and later by Davidson and Triggs using catalytic PdII.[4] Homocoupling reactions of simple substituted arenes (e.g., toluene, anisole, o-xylene) typically suffer from low regioselectivity, and therefore such reactions have limited utility in organic synthesis. An important exception is the oxidative coupling of dimethyl-o-phthalate. This Pd-catalyzed coupling reaction is an important step in the commercial synthesis of 4,4′-biphthalic anhydride (2), [5,6] a monomer used in the high-performance polyimide resin, Upilex® (Scheme 1, Route A), [7] and is the basis for recent industrial interest in the development of improved arene homocoupling methods.[8] Production of the bisanhydride monomer 2 could be streamlined significantly by carrying out direct homocoupling of o-xylene, followed by aerobic oxidation of the benzylic methyl groups of 4,4′-bixylyl 3 (Scheme 1, Route B).[9] A major barrier to implementing this improved synthetic route is the poor selectivity obtained in the homocoupling of o-xylene. Selectivity challenges include regioselectivity, which result in a mixture of bixylyl isomers, and chemoselectivity, associated with overoxidation of bixylyl to afford oligomeric xylyl byproducts. Here, we describe the development of a new chemo- and regioselective method for aerobic oxidative homocoupling of o-xylene [Eq. (2)] and the discovery of 2-fluoropyridine (2Fpy) as a highly effective ligand in this Pd-catalyzed reaction.

Scheme 1.

Existing and proposed alternate routes for the commercial production of the polyimide monomer 2.

|

(2) |

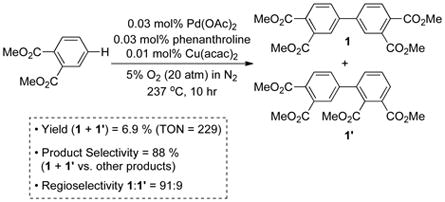

The oxidative coupling of dimethyl-o-phthalate and o-xylene has been the subject of numerous investigations, and the best reported results are presented in Eqs. (3) and (4), respectively.[10] Large-scale reactions of this type are typically stopped at low conversion (≤ 10%) to avoid overoxidation and formation of oligomeric byproducts. The starting materials are recycled to ensure efficient feedstock utilization. In such reactions, product selectivity often becomes a more important measure of the success of the reaction than the single-pass yield. The oxidative coupling of dimethyl-o-phthalate proceeds with sufficient chemo- and regioselectivity [88% and 91%, respectively; Eq. (3)] to be used in the commercial production of 4,4′-biphthalic anhydride 2. In contrast, the oxidative coupling of o-xylene exhibits poor selectivity [40% and 77%, respectively; Eq. (4)].

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

We speculated that the o-xylene coupling reaction could proceed with higher selectivity improved by carrying out the reaction under milder reaction conditions, and that this goal could be achieved by identifying a more active catalyst. With these targets in mind, catalyst screening efforts focused on evaluating reactions at 80 °C, 60 degrees lower than that of the previously optimized conditions (140 °C). This work took place in two phases. Initial studies focused on evaluating combinations of Pd salts (2.5 mol %) with ligands, acid and base additives, and solvents. These screening studies and a brief mechanistic assessment of the optimized conditions were then followed by reoptimization of the catalyst system at 0.1 mol % Pd loading. These efforts are presented in sequence below.

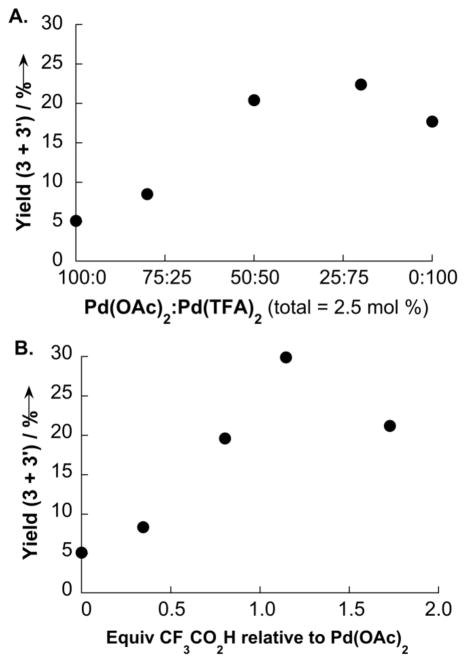

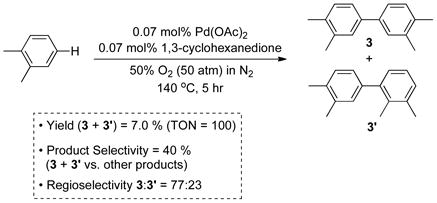

Our ligand screening efforts focused on the evaluation of oxidatively stable nitrogen ligands, which have found significant utility in other Pd-catalyzed aerobic oxidation reactions (see Supporting Information for details).[11] Chelating ligands such as bipyridine and phenanthroline, which have been used successfully in the oxidative coupling of dimethyl-o-phthalate [cf. Eq. (3)], [6d] almost completely inhibited the oxidative coupling of o-xylene at 80 °C (< 1% yield of bixylyl). In contrast, promising results were obtained with monodentate pyridine derivatives (Figure 1). Although little coupling product was obtained with pyridine itself, significant catalytic activity was observed with pyridine derivatives bearing electron-withdrawing groups in the 2-pyridyl position. The best results, by far, were obtained with 2-fluoropyridine as the ancillary ligand (Figure 1). The identity of the anionic ligand also had a significant influence on the reaction, with Pd(OAc)2 exhibiting a lower reactivity than Pd(TFA)2 (TFA = trifluoroacetate). The most effective catalyst systems, however, featured a mixture of acetate and trifluoroacetate anionic ligands (Figure 2). Similar results were obtained by combining Pd(OAc)2 and Pd(TFA)2 (Figure 2A) or by adding CF3CO2H to Pd(OAc)2 (Figure 2B).

Figure 1.

Ancillary ligand effects on the yield of Pd-catalyzed homocoupling of o-xylene. Conditions: o-xylene (3.8 mmol), Pd(OAc)2/CF3COOH, (0.09/0.12 mmol), ligand (0.19 mmol), propylene carbonate (0.4 mL), 1 atm O2, 80 °C, 17 h, GC yield.

Figure 2.

Anionic ligand effects on the oxidative coupling of o-xylene, based on mixtures of Pd(OAc)2/Pd(TFA)2 (A) and Pd(OAc)2/CF3CO2H (B). Conditions: o-xylene (3.8 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 + Pd(TFA)2 (0.09 mmol), 2-fluoropyridine (0.19 mmol), CF3COOH (0–0.12 mmol), propylene carbonate (0.4 mL), 1 atm O2, 80 °C, 17 h, GC yield.

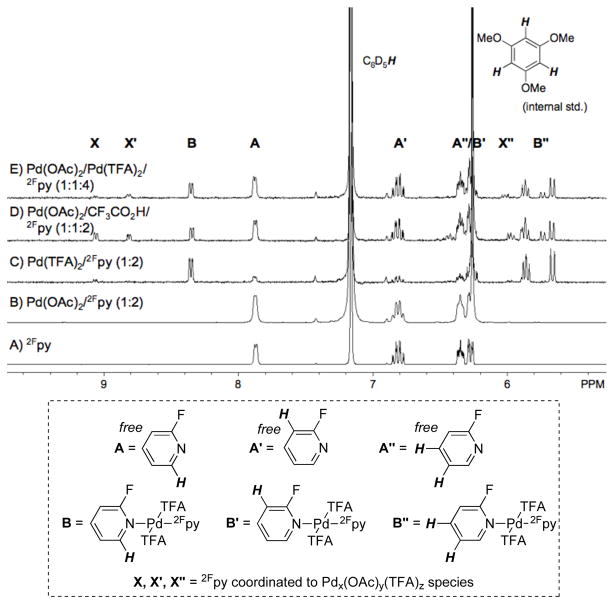

NMR spectroscopic studies provide some insight into the ligand effects (see Figure 3 and Supporting Information). The ortho-fluorine substituent of 2Fpy greatly attenuates its basicity/coordinating ability relative to pyridine, [12] and 1H and 19F NMR spectra of Pd(OAc)2/2Fpy mixtures reveal that 2Fpy does not bind to Pd(OAc)2.[13] The 2Fpy resonances in this spectrum are only those associated with free ligand (cf. Figures 3A, 3B and S1–S2). In contrast, 2Fpy coordinates to Pd(TFA)2 with a 2:1 stoichiometry, and the NMR spectroscopic and X-ray crysallographic data establish the identity of this complex as trans-(2Fpy)2Pd(TFA)2 (Figures 3C and S3-S4).[14] Titration experiments establish that the 2:12Fpy:Pd(TFA)2 stoichiometry is retained even when fewer than two equivalents of 2Fpy are present in solution. The combination of 2Fpy with Pd(OAc)2/Pd(TFA)2 and with Pd(OAc)2/CF3CO2H are more complex. 1H and 19F NMR spectra reveal the presence of (2Fpy)2Pd(TFA)2 in addition to two other species (Figures 3D, 3E and S5-S8). The identities of the latter species have not been fully established, but the data are consistent with 2Fpy coordination to Pd species with both AcO− and CF3CO2− ligands, either as mononuclear or higher-nuclearity Pd complexes.

Figure 3.

1H NMR spectra demonstrating the ability of 2Fpy to coordinate to PdII–trifluoroacetate (TFA) species (spectra C–E), but not Pd(OAc)2 (spectrum B) in C6D6. Conditions: (A) 2Fpy in C6D6; (B) [Pd(OAc)2] = 14.6 mM, [2Fpy] = 30.7 mM; (C) [Pd(TFA)2] = 24.3 mM; [2Fpy] = 51.9 mM; (D) [Pd(OAc)2] = 20.8 mM, [CF3COOH] = 18.7 mM, [2Fpy] = 41.6mM; (E) [Pd(OAc)2] = 6.9 mM, [Pd(TFA)2] = 7.3 mM, [2Fpy] = 31.2 mM.

A large deuterium kinetic isotope effect (kH/kD = 10.7(2.0)) was obtained for the catalytic oxidative coupling reaction by independently measuring the initial rate of bixylyl formation with o-xylene and with o-xylene-d10.[15] This result suggests that C–H activation of o-xylene is the turnover-limiting step of the reaction, and it provides a basis for understanding the empirical ligand screening data in Figures 1 and 2. These data highlight the beneficial effect of electron-deficient ancillary ligands, 2Fpy and TFA, but they also reveal that acetate (~1 equiv with respect to Pd) benefits the reaction. Such observations can be rationalized within the framework of a “concerted metalation-deprotonation” (CMD) pathway for PdII-mediated C–H activation.[16] In such mechanisms, C–H activation is facilitated by two factors: (1) increased electrophilicity of the PdII center and (2) the presence of a basic ligand (such as acetate) that deprotonates the arene C–H bond as the Pd–Caryl bond is forming.

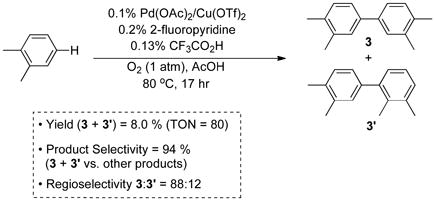

The catalyst system identified from these initial studies [Pd(OAc)2/CF3CO2H/2Fpy (1:1:2)] has a relatively high catalyst loading (2.5%) and low turnover number (12); however, it exhibits improved product selectivity (60%) and regioselectivity (3:3′ = 88:12) relative to the previous-best results [Eq. (4)]. In an effort to develop a more practical catalyst system, the oxidative coupling of o-xylene was reevaluated at 0.1 mol % Pd loading. The initial result was quite poor (Table 1, entry 1). Further optimization, however, revealed that improved results could be obtained by including 0.1 mol % Cu(OTf)2 as a cocatalyst and by replacing propylene carbonate with acetic acid as a solvent (Table 1; see Supp. Info. for additional data).

Table 1.

Optimization data for o-xylene homocoupling at 0.1 mol % Pd loading.[a]

| Entry | Additive (0.1 %) | Solvent | TON [b] | Product Selectivity [%] | Regioselectivity [%][c] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | – | p.c.[d] | 7 | 11 | 68 |

| 2 | Cu(OAc)2 | p.c. | 8 | 41 | 65 |

| 3 | AgOAc | p.c. | 4 | 65 | 38 |

| 4 | Cu(OTf)2 | p.c. | 45 | 63 | 67 |

| 5 | AgOTf | p.c. | 5 | 5 | 69 |

| 6 | Zn(OTf)2 | p.c. | 16 | 29 | 65 |

| 7 | Cu(OTf)2 | AcOH | 80 | 94 | 88 |

| 8 | Cu(OTf)2 | EtCO2H | 74 | 56 | 88 |

| 9 | Cu(OTf)2 | PivOH | 16 | 19 | 67 |

Conditions: o-xylene (3.8 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (0.004 mmol), additive (0.004 mmol), 2-fluoropyridine (0.008 mmol), CF3COOH (0.005 mmol), solvent (0.4 mL), 1 atm O2, 80 °C, 17 h.

Determined by GC yield.

[3/(3 + 3′)] × 100.

Propylene carbonate.

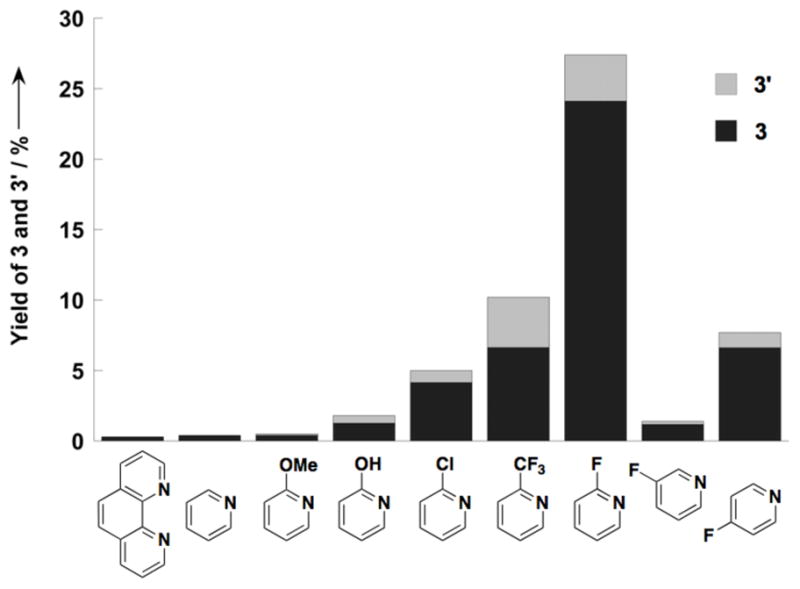

Analysis of ancillary ligand effects with this improved catalyst system revealed that 2-fluoropyridine remains the most effective ligand. A Brønsted plot, based on initial rates of reactions with numerous substituted pyridines, exhibits a “volcano plot” appearance with 2-fluoropyridine at the peak (Figure 4). The presence of paramagnetic Cu species and the low catalyst loading has complicated efforts to probe this catalyst system directly by NMR spectroscopy; however, our previous data (cf. Figures 1–3) provide some clues into the origin of the 2Fpy ligand effect. We hypothesize that pyridines more basic than 2Fpy attenuate the electrophilicity of the Pd catalyst and reduce the catalytic activity. In contrast, pyridines less basic than 2Fpy are poor ligands and, therefore, are unable to modulate the identity and reactivity of the Pd catalyst. The latter hypothesis is supported by 1H and 19F NMR spectroscopic studies, which reveal that 2,4,6-trifluoropyridine and other more-electron-deficient pyridine derivatives do not coordinate to Pd(TFA)2 (see Supporting Information).

Figure 4.

Dependence of the rate of o-xylene coupling on the identity of the ancillary pyridine ligands. The pKa values correspond to those of the pyridinium ions in DMSO. [17] Conditions for initial-rate measurements: o-xylene (3.8 mmol), Pd(OAc)2 (0.02 mmol), Cu(OTf)2 (0.02 mmol), ligand (0.04 mmol), CF3COOH (0.024 mmol), AcOH (0.4 mL), 1 atm O2, 80 °C, initial rate (0–6 h).

Collectively, these results highlight 2-fluoropyridine as a novel, highly effective ligand to support Pd-catalyzed aerobic oxidative coupling of arenes. The high activity of the 2Fpy/PdII catalyst system permits the oxidative coupling of o-xylene to be achieved at temperatures substantially lower than those previously reported, and the improved catalytic results, which include a dramatic increase in the product selectivity (from 40% to 94%) as well as an increase in the regioselectivity (from 77% to 88%) [Eqs. (4) and (5)], provide the potential basis for more-efficient

|

(5) |

feedstock utilization in a large-scale chemical process (cf. Scheme 1). These results have important implications for other reactions as well. The scope and utility of Pd-catalyzed oxidative coupling reactions continues to expand, [1,2] and the identification of oxidatively stable ligands that can support efficient catalytic turnover with O2 as the terminal oxidant is an increasingly important goal for this field. Preliminary results in our lab suggest that 2-fluoropyridine will find broad application to these types of reactions.

Experimental Section

Representative Procedure for Aerobic Oxidative Coupling of o-Xylene

Method A

In a disposable culture tube, palladium complexes (0.094 mmol), 2-fluoropyridine (0.19 mmol), trifluoroacetic acid (0.113 mmol), o-xylene (0.4 g) and propylene carbonate (0.4 g) were combined. The reaction tubes were placed in a 48-well aluminum block mounted on a Large Capacity Mixer (Glas-Col) that enabled several reactions to be performed simultaneously under a constant pressure of (approx 1 atm) with controlled temperature and orbital agitation. The headspace above the tubes was purged with oxygen gas for ca. 5 min. The reactions were vortexed for 17 hr under 1 atm of O2. After the reactions were stopped, n-hexadecane was added to the reaction mixture as an internal standard. Samples were evaluated by GC for the products and remaining starting materials.

Method B

In a 6 ml vial, palladium complexes (0.02 mmol), 2-fluoropyridine (0.04 mmol), trifluoroacetic acid (0.024 mmol) and acetic acid (2 g) were combined and stirred at room temperature for 30 min. The mixture was used as a stock solution. In a disposable culture tube, copper triflate (0.04 mmol) and o-xylene (0.4 g) were combined. Then, the stock solution (0.4 g) was added. Reaction tubes were placed in a 48-well parallel reaction mounted on a Large Capacity Mixer (Glas-Col) that enabled several reactions to be performed simultaneously under a constant pressure of (approx 1 atm) with controlled temperature and orbital agitation. The headspace above the tubes was purged with oxygen gas for ca. 5 min. The reactions were vortexed for 17 hr under 1 atm of O2. After the reactions were stopped, n-hexadecane was added to the reaction mixture as an internal standard. Samples were evaluated by GC for the products and remaining starting materials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. I. A. Guzei and L. C. Spencer for X-ray crystallographic assistance. We are grateful for financial support from Mitsubishi Chemical Corporation (YI) and the NIH (R01 GM67163).

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/adsc.200######.

References

- 1.For leading references, see: Rong Y, Li R, Lu W. Organometallics. 2007;26:4376–4378.Hull KL, Lanni EL, Sanford MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:14047–14049. doi: 10.1021/ja065718e.Stahl SS. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:3400–3420. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300630.Yokota T, Sakaguchi S, Ishii Y. Adv Synth Catal. 2002;344:849–854.Mukhopadhyay S, Rothenberg G, Lando G, Agbaria K, Kananei M, Sasson Y. Adv Synth Catal. 2001;343:455–459.Iretskii AV, Sherman SC, White MG, Kenvin JC, Schiraldi DA. J Catal. 2000;193:49–57.Lee SH, Lee KH, Jung JD, Shim JS. J Mol Catal. 1997;115:241–246.Okamoto M, Yamaji T. Chem Lett. 2001:212–213.

- 2.a) Stuart DR, Fagnou K. Science. 2007;316:1172–1175. doi: 10.1126/science.1141956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Stuart DR, Villemure E, Fagnou K. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12072–12073. doi: 10.1021/ja0745862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Li BJ, Tian SL, Fang Z, Shi ZJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:1115–1118. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Brasche G, Garcia-Fortanet J, Buchwald SL. Org Lett. 2008;10:2207–2210. doi: 10.1021/ol800619c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Hull KL, Sanford MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:11904–11905. doi: 10.1021/ja074395z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Dwight TA, Rue NR, Charyk D, Josselyn R, DeBoef B. Org Lett. 2007;9:3137–3139. doi: 10.1021/ol071308z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Potavathri S, Dumas AS, Dwight TA, Naumieca GR, Hammanna JM, DeBoef B. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:4050–4053. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2008.04.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Cho SH, Hwang SJ, Chang S. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9254–9256. doi: 10.1021/ja8026295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Xi P, Yang F, Qin S, Zhao D, Lan J, Gao G, Hu C, You J. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1882–1884. doi: 10.1021/ja909807f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Helden R, Verberg G. Recl, Trav Chim Pays-Bas. 1965;84:1263–1273. [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Davidson JM, Triggs C. Chem Ind. 1966:457. [Google Scholar]; b) Davidson JM, Triggs C. Chem Ind. 1967:1361. [Google Scholar]; c) Davidson JM, Triggs C. J Chem Soc. 1968:1324–1330. [Google Scholar]

- 5.This process is currently used by Ube industries Ltd. For representative pantents, see: Itatani H, Kashima M, Yoshimoto H, Yamamoto H. 3940426. US Patent. 1976Itatani H, Yoshimoto H, Shiotani A, Yokota A, Yoshikiyo M. 4294976. US Patent. 1981Itatani H, Shiotani A, Yokota A. 33379. JP Patent. 1985

- 6.Efficient catalyst for dimethyl phthalate was reported. See: Iataaki H, Yoshimoto H. J Org Chem. 1973;38:76–79.Yoshimoto H, Itatani H. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1973;46:2490–2492.Yoshimoto H, Itatani H. J Catal. 1973;31:8–12.Shiotani A, Yoshikiyo M, Itatani H. J Mol Catal. 1983;18:23–31.Shiotani A, Itatani H, Inagaki T. J Mol Catal. 1986;34:57–66.

- 7.a) Mohri Y. Seni Gakkaishi. 1994;50:96–101. [Google Scholar]; b) Kreuz JA, Edman JR. Adv Mater. 1998;10:1229. [Google Scholar]

- 8.A NineSigma™ proposal request (#11222-1) was issued in Oct. 2008, entitled “Benzene Ring Catalytic Coupling Technology”, in which a multi-billion dollar chemical manufacturer targeted the development of novel catalysts for the direct coupling of substituted aromatics.

- 9.Aerobic oxidation of bixylyl to biphthalate has been accomplished under conditions similar to the well-established industrial processes for benzylic oxidation, such as the Mid-Century process for commercial production of terephthalic acid from p-xylene: Kumano T, Ogoshi A. 34227. JP Patent. 2003

- 10.Itatani H, Shiotani A, Yoshimoto H, Yoshikiyo M, Yokota A. 79324. JP Patent. 1980

- 11.See, for example: Nishimura T, Onoue T, Ohe K, Uemura S. Tet Lett. 1998;39:6011–6014.Fix SR, Brice JL, Stahl SS. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:164–166. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020104)41:1<164::aid-anie164>3.0.co;2-b.Nishimura T, Araki H, Maeda Y, Uemura S. Org Lett. 2003;5:2997–2999. doi: 10.1021/ol0348405.Andappan MMS, Nilsson P, Larhed M. Chem Commun. 2004:218–219. doi: 10.1039/b311492a.Sheldon RA, Arends IWCE, ten Brink G-J, Dijksman A. Acc Chem Res. 2002;35:774–781. doi: 10.1021/ar010075n.Yoo KS, Park CP, Yoon CH, Sakaguchi S, O’Neill J, Jung KW. Org Lett. 2007;9:3933–3935. doi: 10.1021/ol701584f.Zhang YH, Shi BF, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:5072–5074. doi: 10.1021/ja900327e.

- 12.Brown HC, McDaniel DH. J Am Chem Soc. 1955;77:3752–3755. [Google Scholar]

- 13.In contrast, pyridine coordinates to Pd(OAc)2 in a 2:1 stoichiometry. See: Steinhoff BA, Guzei IA, Stahl SS. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:11268–11278. doi: 10.1021/ja049962m.

- 14.See Supporting Information for the X-ray crystallographic data.

- 15.KIEs measured previously for Pd-catalyzed homocoupling of arenes have been somewhat smaller (KIE ~ 5). See ref. 4c and the following: Shue RS. J Am Chem Soc. 1971;93:7116–7117.Stock LM, Tse K, Vorvich LJ, Walstrum SA. J Org Chem. 1981;46:1757–1759.Kashima M, Yoshimoto H, Itatani H. J Catal. 1973;29:92–98.Ackerman LJ, Sadighi JP, Kurtz DM, Labinger JA, Bercaw JE. Organometallics. 2003;22:3884–3890.

- 16.a) Gorelsky SI, Lapointe D, Fagnou K. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:10848–10849. doi: 10.1021/ja802533u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Davies DL, Donald SMA, Macgregor SA. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:13754–13755. doi: 10.1021/ja052047w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Garcia-Cuadrado D, Braga AAC, Maseras F, Echavarren AM. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1066–1067. doi: 10.1021/ja056165v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Balcells D, Clot E, Eisenstein O. Chem Rev. 2010;110:749–823. doi: 10.1021/cr900315k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The pyridinium pKa values were obtained from ref. 12 and the following references. In cases where literature data are not available (4-fluoro-, 2,4,6-trifluoro-, 2,3,5-trifluoro- and 2-fluoro-4-trifluoromethylpyridinium), the pKa values are those reported in SciFinder Scholar based on calculations using Advanced Chemistry Development (ACD/Labs) Software V 11.02. Bordwell FG. Acc Chem Res. 1988;21:456–463.Chakrabarty MR, Handloser CS, Mosher MW. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 2. 1973;7:938–942.Clarke K, Rothwell K. J Chem Soc. 1960:1885.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.