Abstract

Background

The Veterans Aging Cohort Study (VACS) is a study of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected and uninfected patients seen in infectious disease and general medical clinics. VACS includes the earlier 3 and 5 site studies (VACS 3 and VACS 5) as well as the ongoing 8 site study.

Objectives

We sought to provide background and context for analyses based upon VACS data, including study design and rationale as well as its basic protocol and the baseline characteristics of the enrolled sample.

Research Design

We undertook a prospectively consented multisite observational study of veterans in care with and without HIV infection.

Measures

Data were derived from patient and provider self report, telephone interviews, blood and DNA samples, focus groups, and full access to the national VA “paperless” electronic medical record system.

Results

More than 7200 veterans have been enrolled in at least one of the studies. The 8 site study (VACS) has enrolled 2979 HIV-infected and 3019 HIV-uninfected age–race–site matched comparators and has achieved stratified enrollment targets for race/ethnicity and age and 99% of its total target enrollment as of October 30, 2005. Participants in VACS are similar to other veterans receiving care within the VA. VACS participants are older and more predominantly black than those reported by the Centers for Disease Control.

Conclusions

VACS has assembled a rich, in-depth, and representative sample of veterans in care with and without HIV infection to conduct longitudinal analyses of questions concerning the association between alcohol use and related comorbid and AIDS-defining conditions.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, alcohol, aging veterans, data management/research design

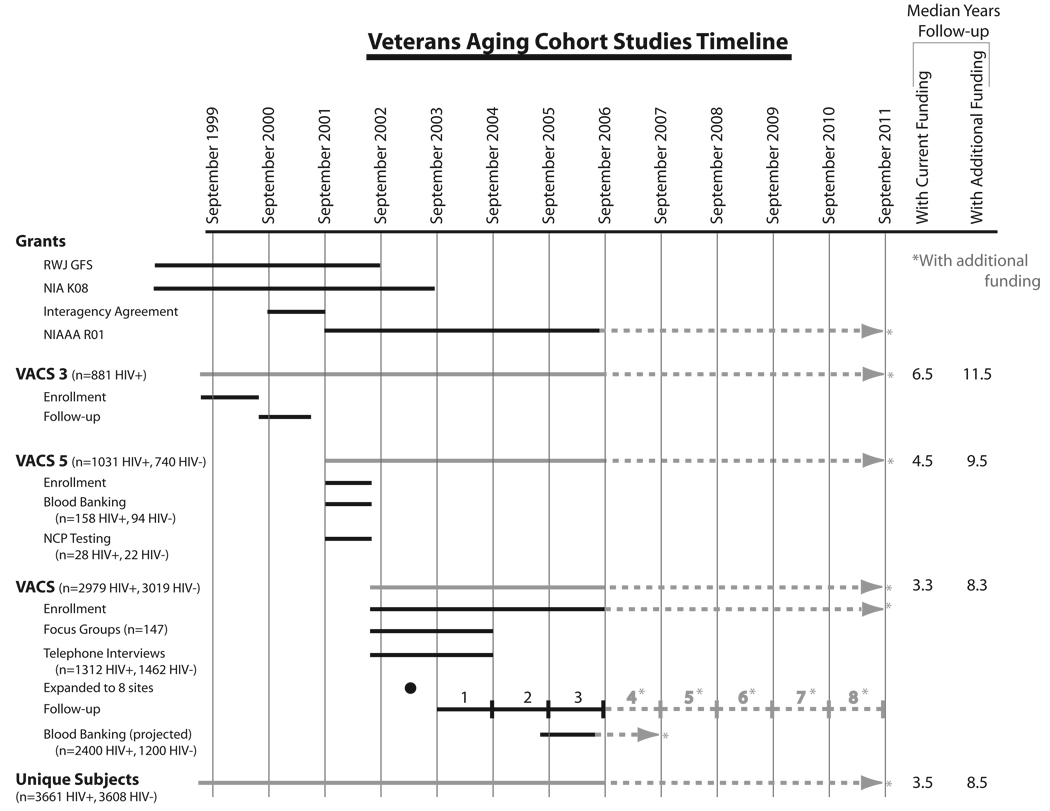

The Veterans Aging Cohort Study (VACS) is a longitudinal, prospective multisite observational study of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected and uninfected patients seen in Veterans Administration Medical Center (VAMC) infectious disease and general medical clinics. VACS includes the earlier 3 and 5 site studies (VACS 3 and VACS 5) as well as the ongoing 8 site study. All patients included have provided written consent. It is focused on the role of alcohol use, abuse, and dependence on HIV infection in the larger context of aging, comorbid disease, and long-term antiretroviral treatment. VACS is funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism at the National Institutes of Health and is in its 7th year (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Veterans Aging Cohort Studies Timeline.

Begun in 1999 as a 3-site study of 881 veterans with HIV infection (Fig. 1, VACS 3), VACS expanded to 5 sites (VACS 5) and added HIV-uninfected age–race–site group matched veteran comparators in 2001 with support from National Institute on Aging and National Institute for Mental Health. VACS 3 and VACS 5 were focused on comorbidity and behaviors that we hypothesized would affect outcomes in HIV. Major strengths of these studies were the predominance of black and or Latino/a (approximately 70–80% of all VACS samples) and their older age (median age ~50 years). The combination of older individuals and racial and ethnic diversity allowed us to begin to understand how comorbidity and behavior impact outcomes as individuals of different racial and ethnic backgrounds age with HIV infection.

As part of these early studies, we included the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), a self-completed screening measure for hazardous alcohol use.1 Using this measure, we were impressed by the prevalence of hazardous drinking and applied to National Institutes of Health for funds to support further work in this area. VACS initially received 5 years of funding from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism in September of 2001 to study the association of alcohol with patient outcomes among those with and without HIV infection. Additional funding in 2002 and 2003 allowed VACS to expand to 8 sites and to plan and initiate full-scale blood and DNA banking. A renewal application for 5 more years of funding support is currently under review.

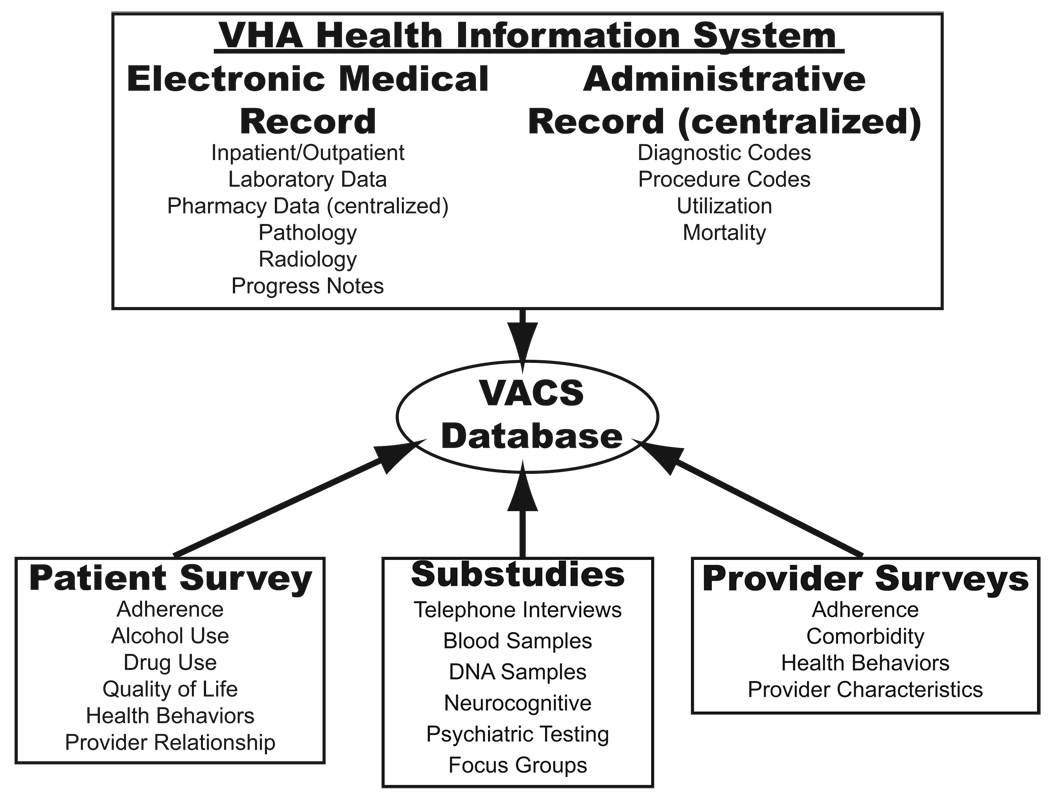

VACS and the virtual cohort (described in a separate report in this supplement) are built on the substantial infrastructure in place within the VA Healthcare System with direct access to all electronic medical records (EMRs) and administrative data (Fig. 2). These data has been supplemented with patient and provider surveys, in-depth telephone interviews, blood and DNA banking, neuropsychiatric testing, and patient and provider focus groups. The availability of multiple sources of data has allowed us to conduct extensive validation studies of EMR and administrative data sources.

FIGURE 2.

Data sources available in VACS.

Our short-term objective is to compare differences in outcomes associated with alcohol use, comorbid conditions, and treatment toxicity in veterans with and without HIV disease. Because alcohol use is common among those with HIV infection, the role of alcohol is a major focus. Our long-term objective is to use these data and the EMR to design and implement effective interventions to improve outcomes among patients with HIV infection. These interventions will include computer-supported assessment of individualized risk and preferences, which will in turn inform intervention prioritization, including motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral therapy. This report summarizes the history, design, data sources, and data elements used in the VACS.

METHODS

Overlap Among VACS 3, VACS 5, and VACS Samples

This report summarizes VACS 3, VACS 5, and the “full study” or VACS. As can be seen on the timeline of enrollment and follow-up (Unique patients, Fig. 1), there is overlap. As of this writing and taken together, the VACS 3, VACS 5, and full studies have enrolled and will follow for long-term outcomes more than 7200 unique veterans (3661 HIV+, 3608 HIV−) from 9 sites. (One site included in VACS 3 has not participated in subsequent studies, ie, Cleveland, Ohio.) The full study (VACS) includes 83% of all these subjects (81% of the HIV+, 84% of the HIV− veterans). Considering only HIV infected subjects: 196 of 881 (22%) of VACS 3 subjects and 861 of 1031 (84%) of VACS 5 subjects enrolled in the full study. Because the full study will continue to enroll, these numbers will change over time.

VACS 3 and VACS 5

The 3 site study (VACS 3) has been described in detail2 and is included, with the other studies, in Figure 1. VACS 5 included 1 patient and 1 provider survey as well as full access to each participant’s electronic medical record. It was conducted at 5 VA medical centers (Atlanta, GA; Bronx, NY; Los Angeles, CA; Manhattan/Brooklyn, NY; and Houston, TX). Because it was designed as a feasibility study for the full VACS, the study’s methods used for establishing target enrollment and consenting subjects were the same as described herein.

From September 2001 through June 2002 veterans (1031 HIV+; 740 HIV−) were enrolled. HIV-infected participants in VACS 5 both had a median age of 49 years and were 99% male. Nonparticipants were more likely to be black, have fewer clinic visits, higher viral loads, and to have been on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) for a shorter period of time (P < 0.05).

VACS 5 patients participated in 2 pilot substudies: neurocognitive and psychiatric testing (n = 50) and blood sampling and banking (n = 254). The neurocognitive and psychiatric testing portion of the study has been described in detail.3

The blood and DNA banking involved asking patients to donate samples of blood for future testing of other laboratory markers not commonly ordered during routine visits. Tests conducted on these samples included iron, vitamin B12, folate, homocysteine, mitochondrial AST in serum, and mitochondrial DNA damage. These results will be reported separately (manuscripts in preparation).

VACS (Full Study)

Before enrollment began, all study sites received approval for the use of human subjects by their respective Internal Review Boards (IRBs) as well as overall approval for the VACS Coordinating Center, initially located at the Pittsburgh VA. In July 2003, the Coordinating Center relocated to the VA in West Haven, Connecticut. Principal Investigators, study coordinators, data analysts, and all personnel associated with this project have undergone required training in human subjects protection, good clinical practices, privacy (or Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act [HIPPA]) and conflict of interest. New study coordinators at each site are trained by an experienced VACS coordinator.

VACS opened to enrollment in June of 2002 initially at the same aforementioned VACS 5 sites. In February of 2003, 3 new sites were added: Baltimore, Maryland; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; and Washington DC. Patients are enrolled from the infectious disease (HIV-infected) or general medical clinics (age-, race-, gender-, site-matched uninfected comparators). In either clinic, patients are assigned to a single primary care provider who may have been a general internist, an infectious disease specialist, a physician assistant, or an advanced practice registered nurse. Baseline enrollment for reporting purposes is defined as lasting from June 2002 to September 2004. During this interval, 5998 subjects enrolled (2979 HIV+, 3019 HIV−). The study continues to enroll new HIV infected subjects and age/race/site-matched uninfected comparators to replace those who have died or are lost to follow-up to avoid becoming a “survival cohort” and requires an annual enrollment of approximately 5% of the overall sample. Survival cohorts occur when samples are identified in 1 period and then followed for an extended time without further enrollment. A survival cohort no longer represents the target population because individuals are required to have lived an extended period after presentation to be included in the sample.

Each site is monitored by a Principal Investigator, Co-Principal Investigator, and study coordinator. The study coordinator recruits HIV-infected participants from the infectious disease clinics and an age/race/site-matched HIV-uninfected comparators from the general medicine clinics. The study is explained to the participants in detail, and once written informed consent is obtained, the participants are asked to complete a questionnaire before leaving the clinic. The participants’ providers are asked to complete a shorter questionnaire that contains questions specific to that patient on the day of his/her appointment and a one-time provider characteristic questionnaire which asks for details on the provider’s practice, caseload and training. The questionnaires are developed using Teleform software (Verity, Sunnyvale, CA), which allows investigators to both design surveys and enter data collected via scanning technology.

Follow-Up

Using the EMR, we determine the number of patients who are deceased or lost to follow-up on an annual basis. For purposes of reporting, we define lost to follow-up as those who have not been seen within the VA system for 12 months. Sometimes these patients return to the study in subsequent follow-up. Further, no veteran is truly “lost to follow-up” with respect to mortality endpoints. We eventually achieve mortality endpoints even on patients considered “lost” because of the availability of a death benefit paid to defray funeral expenses for all veterans.4,5 In a 12-month period, approximately 2.5% of the HIV-infected veterans (not known to be dead) who received VA care in the previous 12 months will not receive it in the subsequent 12 months. For HIV-negative comparators, the proportion is 4%.

The first annual survey follow-up occurred from September 2003 to September 2004. The VA sites in Baltimore, Maryland, and Washington, DC, did not participate in this initial follow-up as baseline enrollment was still underway. The second follow-up occurred from October 2004 to September 2005. A third wave of follow-up surveys is currently underway. All sites have also begun enrolling VACS patients in the blood and DNA banking substudy.

Target Sample Calculation

Using the VA Immunology Case Registry of all HIV-infected veterans in care,6 the number receiving HIV care was determined by VA site and clinic. Target enrollment was set at 65% of HIV-infected patients receiving care at each Infectious Disease clinic in fiscal year 2002 and was stratified based on age and race for each site. Targets for controls were set for each site to match the HIV infected site enrollment targets by age and race.

Recruitment

Once permission from the providers is obtained, study coordinators approach patients as they arrived at the clinics for their regular appointments. The coordinators describe the nature of the study and obtain informed consent. Patients are given the option, if eligible, to enroll in the telephone interview substudy, which requires a separate consent form. Patients are then given a paper questionnaire to be completed before the end of the clinic visit and are paid $20 for their participation. By signing the informed consent, participants give their permission for study investigators to review all electronic medical records. Patients also grant permission to be recontacted in the future.

Patient Surveys

With few exceptions, standardized instruments are used in each questionnaire (Table 1).7–35 There are items concerning medical conditions, health (such as height, weight, frequency of exercise, smoking), as well as questions regarding homelessness, income, health care utilization, satisfaction with care, health-related quality of life, medical care and insurance outside the VA, employment and education, and race/ethnicity, gender, and date of birth. Most of these items were also used in the Veterans Health Survey, a national sample of all eligible veterans.9a We adapted these measures to allow benchmarking against this representative sample of veterans. The questions for health conditions are expanded in the infectious disease questionnaire to include AIDS-defining conditions using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention list.11

TABLE 1.

VACS Survey and Other Supplementary Data Items

| Source of Measure | Sample Collected* | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Survey Items | Self-completed by patient | ||

| Comorbidity | Veterans Health Survey | 3, 5, B, F1, F2, F3 | 9a, 10 |

| AIDS Defining Conditions | VACS 5 | 5, B, F1, F2, F3 | 11 |

| Health & Habits (Weight, Height, Exercise) | Veterans Health Survey | 5, B, F1, F2, F3 | 9a, 10 |

| Alternative therapies | VACS 3 | 3, 5, B, F1, F2, F3 | 2 |

| Homelessness | VACS 3 | 5, B, F1, F2, F3 | 2 |

| Alcohol (Hazardous Use, Screening) | AUDIT or AUDIT-C | 3, 5, B, F1, F2, F3 | 1, 12 |

| Alcohol (Consequences) | Short Inventory of Problems (SIPS) | B, F1, F2 | 13 |

| Alcohol (Dependency) | Alcohol Dependency Scale (ADS) | F1, F2 | 14 |

| Alcohol (Expectancies) | F2 | 14, 15 | |

| Alcohol (Symptoms) | F1 | 14, 15 | |

| Alcohol (Readiness to Change) | SOCRATES, RTC Ladder | F2, F3 | 16, 17 |

| Tobacco | Veterans Health Study | 5, B, F1, F2, F3 | 9a, 10 |

| Tobacco Readiness to Change | RTC Ladder for Smoking | F2, F3 | 17 |

| Drugs (Illicit drugs) | DAST-10 | 3, B, F1, F2, F3 | 18 |

| Drugs (Prescription drug abuse) | NSDUH | F2, F3 | 19 |

| Drugs Readiness to Change | RTC Ladder for Drugs | F2, F3 | 17 |

| Risky sexual and drug use behavior | Centers for Disease Control | 5, B, F1, F2, F3 | 20 |

| Social aspects of health, social contacts & coping | HCSUS | 5, B, F1, F2, F3 | 21 |

| Religiosity/spirituality | Elder Care Research Center | 5, B, F1, F2 | E. Kahana, PhD |

| Health care utilization & accessibility | Veterans Health Survey | 5, B, F1, F2 | 9a, 10 |

| Trust in provider/quality of care | Veterans Health Survey | 3, 5, B, F1, F2, F3 | 9a, 10 |

| Medical care & insurance outside VHA | Veterans Health Survey | 3, 5, B, F1, F2, F3 | 9a, 10 |

| Medication adherence | AIDS Clinical Trails Group | 3, 5, B, F1, F2, F3 | 21a |

| Symptom burden | AIDS Clinical Trails Group | 3, 5, B, F1, F2, F3 | 23 |

| Symptoms of Depression & Anxiety | PRIME MD, BECK, BECK | 3, 5, B, F1, F2, F3 | 24–26 |

| Health Related Quality of Life & Functional Status Demographics | Short Form 12, Medical Outcomes Study | 3, 5, B, F1, F2, F3 | 27, 28 |

| Education/Race/Ethnicity/Marital Status/ Employment/Date of Birth/Sex/Income | Veterans Health Survey | 3, 5, B, F1, F2 | 9a, 10 |

| Provider Survey Items | (Self completed by provider) | ||

| Provider Characteristics | VACS 5 | 5, B, F1, F2, F3 | 29 |

| Provider Assessment of Patient | VACS 3 | 3, 5, B, F1, F2, F3 | 2 |

| Cause of Death | CHORUS | One-time form | 7 |

| Telephone Interview (substudy during B & F1, n = 3147, 1173) | Centrally Conducted by UCSUR, University of Pittsburgh |

||

| Alcohol use (current and past) | 30 Day TLFB, Lifetime Drinking History | F1, F2 | 30, 31 |

| Medication Adherence | Modified 30 Day TLFB | F1, F2 | 8 |

| Diagnosis of Abuse or Dependence | CIDI Substance Abuse Module | F1 | 9 |

| Blood Samples (VACS 5 substudy n = 252) | |||

| AST, mAST, cAST, | M. Gerschenson, U. of Hawaii | 5 | 32–34 |

| B12, Folate, Homocystine, Cytokines | D. Taub, NIA Intramural Program | 5 | |

| Neuropschiatric Testing (VACS 5 substudy n = 50) | |||

| HNRC Neuropsychiatric Battery | HIV Neurobehavioral Research Ct., University of California San Diego |

5 | 35 |

Refers to the surveys which included the measure. The number (3, 5) refers to VACS 3 (3) and VAC 5 (5). The letters with or without numbers (B, F1, F2, F3) refer to the full study baseline (B), follow-up 1 (F1), follow-up 2 (F2), follow-up 3 (F3).

The surveys also include detailed information regarding substance use (alcohol, cigarettes, and both illicit and prescription drugs of abuse; Table 1). These items attempt to capture details of current patterns of use as well as prior use and whether use was discontinued due to health problems. Additionally, information concerning readiness to change current substance use behaviors is also being collected for alcohol, cigarette, and drug use.

Other domains that are collected by self report include social aspects of health, social contacts and coping, religiosity and spirituality, medication adherence, symptom burden, symptoms of depression and anxiety, health-related quality of life, and functional status (Table 1). In addition, participants from the general medicine clinics are asked whether they have ever been tested for HIV and if they think they might be at risk. Participants from the infectious disease clinics are instead asked when they had their first positive HIV test and how many months had elapsed until they sought treatment.

Provider Surveys

Two separate provider questionnaires are administered (Fig. 2); the first is a one-time provider characteristic questionnaire, which is given to both general medicine and infectious disease providers. This questionnaire is designed to provide information on provider demographics, specialties, degrees, years in practice and caseload makeup and is described in detail elsewhere.20 The other provider questionnaire is administered to coincide with the patient’s visit and was developed to provide information from the provider about that particular patient. This questionnaire is given annually at all follow-up visits. General medicine and infectious disease providers received separate questionnaires; in the full study, the infectious disease version was expanded to include questions concerning HIV conditions and medications.

Death and Cause of Death

On a quarterly basis, we conduct searches of the Beneficiary Identification Records Locator Subsystem (BIRLS, a benefit paid to defray the costs of burial) and inpatient files in the EMR to determine whether any VACS subject has died. This approach has been favorably compared with the use of the National Death Index.5 Similarly, study coordinators also report deaths directly to us. Once a death has been identified, the study coordinator is notified and he/she collaborates with the primary care provider to complete a cause of death form, which provides information on date and cause of death, if known. These forms and supporting electronic medical record data are reviewed by a standing “Cause of Death Committee” to insure that the forms are completed in a consistent manner. The form used and the manner of review completely parallel that described by the Collaborations in HIV Outcomes Research-US cohort.7

Blood and DNA Sampling

VACS is working in partnership with the Massachusetts Veterans Epidemiology Research and Information Center in Boston, Massachusetts, and the Palo Alto Cooperative Studies Program Coordinating Center in Palo Alto, California, to coordinate a major blood and DNA banking substudy. All of the HIV-positive and 50% of HIV-negative patients already enrolled in VACS will be asked to donate a sample of blood for further testing (target is 80% of the enrolled HIV-infected veterans and 40% of enrolled HIV-negative veterans). The protocol for blood banking encompasses prospective assays not routinely performed at the VA. Initial tests will include those to determine evidence of liver injury, cardiac injury and bone marrow function. Additional assays on banked specimens will involve studies related to alcohol, aging, comorbidity and drug toxicity and will be based upon a formal review process.

In addition, VACS in conjunction with VA Cooperative Studies DNA Bank36 will store DNA and plasma from consenting patients. The DNA will be used for future studies of genetic factors associated with HIV, HIV treatment, alcohol use and comorbid conditions. Proposals for these studies will be reviewed under a separate process.

Telephone Interview

To capture in-depth information on alcohol use, abuse and dependence, and medication adherence, participants in the full study were asked to participate in a telephone interview. Participants were eligible if they had consumed 1 drink during their lifetime. Patients who refused the telephone interview were still permitted to continue their participation in the full study.

Telephone interviews were conducted by experienced interviewers at the University Center for Social and Urban Research at the University of Pittsburgh. The interviewers were qualified by senior research investigators in the standards of best practices specific to the alcohol instruments used in the interview. Additional interviewer training included role-playing, mock interviewing, and qualifying interviews to insure optimal skill and technique. The baseline telephone interview substudy has been described in detail elsewhere.8

A subset of the participants in the baseline telephone interview were called 1 year later for a second interview (n = 1173, 77% of target). This second interview used items from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) and items modified from the Substance Abuse Module (SAM).9 Data are currently in the analysis phase. Future plans include a validation of the TLFB in a subset of patients at 4 of the 8 study sites.

Focus Groups

During the first year of baseline enrollment for the full study, 16 patient focus groups were conducted at all 8 VAMC study sites (total n = 147). The primary purpose of this substudy was to gather qualitative data that would inform the development of behavioral interventions to improve outcomes for patients, particularly related to alcohol use and management of their chronic diseases. These groups consisted of separate groups of approximately 8–12 General Medicine (HIV uninfected) and Infectious Disease (HIV infected) study participants.

Participants in the patient focus groups were paid $25 for their time. Discussion explored patient beliefs, attitudes, experiences, and behaviors relating to alcohol and substance use and abuse and their impact on chronic disease, including HIV infection. The particular focus was on positive behavior change; other health behaviors were explored, such as adherence to medications and healthy lifestyle choices as they affect outcomes. This qualitative data will be reported separately and will be used to inform the design of a clinical intervention to help patients reduce or abstain from alcohol use or abuse and to adopt healthy behaviors.

During the second year of the full study, provider focus groups were held at all study sites. A total of 47 infectious disease providers and 53 general medicine providers participated. Topics for discussion included: ways of helping patients change behavior, support services at the VA, and the use of computer reminders. Providers were not paid for their time.

All focus groups were facilitated at all sites by Martha Terry, PhD, of the University of Pittsburgh and lasted an hour. Food and nonalcoholic beverages were provided. All focus groups were audiotaped and were then transcribed. Analysis of common themes of discussion is underway and will be reported separately.

EMRs

The VA has an advanced centralized electronic administrative records system in Austin, Texas, that allows for national tracking and information on all veterans receiving care from VA services throughout the country; this database also provides health care utilization information and ICD-9 codes.37,38 In addition, all VA medical centers have a Computerized Patient Record System that contains abundant demographic and clinical information useful to the study; in particular, the Computerized Patient Record System is used to extract laboratory data at each site with support from each local Information Resource Management office.39 The Pharmacy Benefits Management database provides medication information including type of medication, dose, and fill dates.38 As mentioned previously, BIRLS provides information on application for death benefits for VA patients.5,40 Data from BIRLS and inhospital mortality will complement data from the Cause of Death forms and will help to complete uncollected death data at the individual sites.

Quality Control

Each site has a team consisting of a Principal Investigator (an infectious disease provider), a Co-Principal Investigator (a general medicine provider), 1 or 2 study coordinators, and a member of the Community Advisory Board (CAB). Local IRB approval has been granted at each site.

The Coordinating Center in West Haven, Connecticut, serves as a source for survey design, development and printing, data analysis, and procedural protocol. Regular contact with sites is maintained through conference calls (PIs, study coordinators, writing committees, survey committees, data analysts) daily e-mails, telephone calls, faxes, and writing. In addition, the Coordinating Center drafts the Manual of Operations, maintains the study website, receives completed surveys and electronic downloads, reviews proposals for data analysis and manuscripts, oversees the grant and budget, organizes scientific meetings, addresses problems at the sites, monitors recruitment, and keeps records of all IRB documentation including initial submissions, renewals, amendments, modifications and consent forms. The Project Coordinator makes annual visits to each site to ensure standardized procedures across all sites, review IRB documentation, observe consent and recruitment procedures, organize focus groups, check patient files for accuracy and protection from unauthorized access, and meet with all members of the site study team to address problems. In addition, an annual face-to-face scientific meeting is held near one of the participating sites. Details of the administrative structure of VACS can be found on the study website: www.vacohort.org.

Alcohol Measures

In an effort to describe the landscape of alcohol-related effects in chronic HIV infection and to contrast them with uninfected comparators, we have collected a wide range of alcohol and substance use measures (Table 1, see editorial in this issue). These have included measures of screening, diagnosis, consequences, dependency, expectancies, and symptoms. We conducted telephone interviews to collect current and lifetime patterns of consumption on half the sample enrolled at baseline and a quarter of the sample enrolled at the first 12 month follow-up. Some instruments, such as the stages of change and readiness to change for alcohol and cigarettes were collected expressly with the intent of developing behavioral interventions.

Data Sources and Analysis

To give the most up to date summary of VACS, we report enrollment as of September 30, 2004 (n = 5998). VA data reported in relation to target enrollments, participants versus nonparticipants, and the National VA sample come from administrative data (age, race/ethnicity, and gender), the VA EMR (pharmacy and laboratory packages), and all available sources (listed above). Centers for Disease Control data represent persons living with HIV/AIDS from the 33 states reporting in 2003.

HAART was defined, after consultation with our clinical experts, as being on at least 3 antiretrovirals at once. To make groups comparable with respect to proportion on HAART (Table 2) regimens reported we restricted all samples to those for whom: first date of HIV care occurred after fiscal year 1998, who had a CD4 cell count from 30 days before first HIV diagnosis to 7 days after, and who had at least some pharmacy use. The sample sizes for these proportions are restricted with respect to the overall sample for each source reported (VACS n = 660/2979; nonparticipants n = 432/2151; virtual cohort n = 5059/33420). All p values reported in table 2 were estimated using binomial for proportions and difference between 2 population means for continuous data.

TABLE 2.

HIV Infected: VACS Participants, Nonparticipants, and VA and CDC National Benchmarks

| VACS Sites | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | Nonparticipants | P | National VA HIV Data |

P | CDC | P | |

| No. | 2979 | 2151 | 33420 | 347549 | |||

| Age, yr | |||||||

| 25–34 | 5% | 7% | 0.0001 | 4% | 0.0001 | 20% | 0.0001 |

| 35–44 | 24% | 26% | 22% | 43% | |||

| 45–54 | 46% | 39% | 44% | 27% | |||

| 55–64 | 19% | 19% | 21% | 8% | |||

| 65+ | 5% | 7% | 8% | 2% | |||

| Race | |||||||

| White, not Hispanic | 21% | 20% | 0.0001 | 32% | 0.0001 | 39% | 0.0001 |

| Black, not Hispanic | 70% | 49% | 43% | 48% | |||

| Hispanic | 9% | 7% | 8% | 12% | |||

| Other/unknown | 0% | 25% | 17% | 1% | |||

| Gender (male) | 96% | 98% | 0.300 | 98% | 0.5 | 75% | |

| Hospitalizations/n | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.700 | 0.3 | 0.3 | NA | |

| CD4 count (cells/mm3) | 330 | 338 | 0.0001 | 323 | 0.0001 | NA | |

| Viral load (copies/mL) | 1316 | 1366 | 0.0001 | 1398 | 0.0001 | NA | |

| Mortality (deaths/100 PY) | 3.41 | 4.32 | 0.08 | 3.46 | 0.9203 | NA | |

| HAART 1st year | 75% | 76% | 0.500 | 80% | 0.0001 | NA | |

| If CD4 <200 | 93% | 93% | 0.9 | 93% | 0.9 | NA | |

| Combinations | |||||||

| Only NRTIs | 4% | 7% | 0.0001 | 6% | 0.0001 | NA | |

| PI(s) with NRTIs | 48% | 47% | 44% | NA | |||

| NNRTI(s) with NRTIs | 43% | 41% | 44% | NA | |||

| PI(s), NNRTI(s), NRTIs | 4% | 5% | 7% | NA | |||

| Other combinations | 1% | 0% | 0% | NA | |||

National VA Data derived from the National Patient Care Database and Immunology Case Registry as described in Fultz et al.29

Centers for Disease Control Data represents persons living with HIV/AIDS from the 33 states reporting in 2003.

Ten-year increments in age are used in order to allow comparison with published data on comparator HIV positive populations.

Data reported in Tables 3 and 4 come from the patient self completed survey. Of note, these data vary from administrative data on race/ethnicity (reported in Table 2). Administrative data on race/ethnicity is determined by inspection by the clinic clerk whereas the survey data reflects the patient’s own determination. While patient self report is preferred, targets could only be established using administrative sources. P values reported in Table 3 reflect results of binomial tests and χ2 tests.

TABLE 3.

VACS Sociodemographics

| HIV+ | HIV− | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 2979 | 3019 | |

| Age (median) | 49 | 50 | 0.002 |

| Gender (% male) | 98% | 92% | 0.0001 |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| White, not Hispanic | 21% | 26% | |

| Black, not Hispanic | 70% | 64% | |

| Hispanic | 9% | 10% | |

| Other/unknown | 0% | 0% | |

| VA/all other healthcare utilization (%) | |||

| Inpatient care | 72.0% | 70.6% | 0.5 |

| Outpatient care | 74.1% | 71.5% | 0.1 |

| Mental Health care | 76.8% | 85.3% | <0.0001 |

| Marital status | <0.0001 | ||

| Married | 14% | 34% | |

| Divorced | 25% | 28% | |

| Separated | 12% | 9% | |

| Widowed | 5% | 4% | |

| Never married | 35% | 19% | |

| Living with partner | 9% | 6% | |

| Employment | <.0001 | ||

| Employed | 27% | 33% | |

| Self-employed | 7% | 8% | |

| Looking for work | 7% | 10% | |

| Homemaker | 6% | 8% | |

| Student | 1% | 1% | |

| Retired | 2% | 2% | |

| Unable to work | 14% | 15% | |

| Unemployed | 36% | 22% | |

| Annual income | <0.0001 | ||

| <$6,000 | 18% | 20% | |

| $6,000–$11,999 | 31% | 19% | |

| $12,000–$24,999 | 24% | 24% | |

| $25,000–$49,999 | 17% | 23% | |

| >$50,000 | 7% | 11% | |

| Education | 0.5 | ||

| <High school | 7% | 9% | |

| HS graduate | 22% | 22% | |

| GED | 11% | 10% | |

| 1–3 yr college | 44% | 44% | |

| College graduate | 10% | 10% | |

| Graduate school | 5% | 5% | |

| Homelessness | |||

| Homeless (last 4 wk) | 11% | 12% | 0.4 |

| Homeless (ever) | 48% | 41% | <0.0001 |

TABLE 4.

Health Behaviors and Conditions

| HIV+ (%) | HIV− (%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 2979 | 3019 | |

| Tobacco use | |||

| Current smoker (last week) | 51% | 41% | <0.0001 |

| Past smoker only | 25% | 29% | 0.001 |

| Pack years (current, median) | 22.7 | 24.2 | 0.2 |

| Alcohol use | |||

| Current consumption (last 12 mo) | 64% | 63% | 0.4 |

| Past consumption only | 31% | 32% | 0.6 |

| 6 or more drinks/d (current only) | 27% | 28% | 0.08 |

| AUDIT of 8+ | 16% | 18% | 0.004 |

| Illicit drug use | |||

| Current use (last 12 mo) | 41% | 27% | <0.0001 |

| Marijuana | 28% | 17% | |

| Cocaine | 21% | 14% | |

| Stimulants | 4% | 2% | |

| Opiates | 9% | 7% | |

| Other | 2% | 2% | |

| Weight (body mass index) | |||

| Underweight (<20) | 7% | 2% | <0.0001 |

| Normal weight (20–24.9) | 42% | 20% | |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 36% | 36% | |

| Obese (>30) | 15% | 41% | |

| Exercise | |||

| None | 14% | 11% | 0.002 |

| <1 ×/week | 17% | 19% | |

| 1–2 ×/week | 24% | 26% | |

| 3–4 ×/week | 27% | 25% | |

| 5 or more ×/week | 18% | 19% | |

| Functional status | |||

| SF-12 MCS [median (IQR)] | 32.4 (26.8–38.1) | 32.9 (27.3–38.3) | 0.1 |

| SF-12 PCS [median (IQR)] | 42.2 (35.2–51.9) | 41.2 (34.9–50.1) | 0.002 |

RESULTS

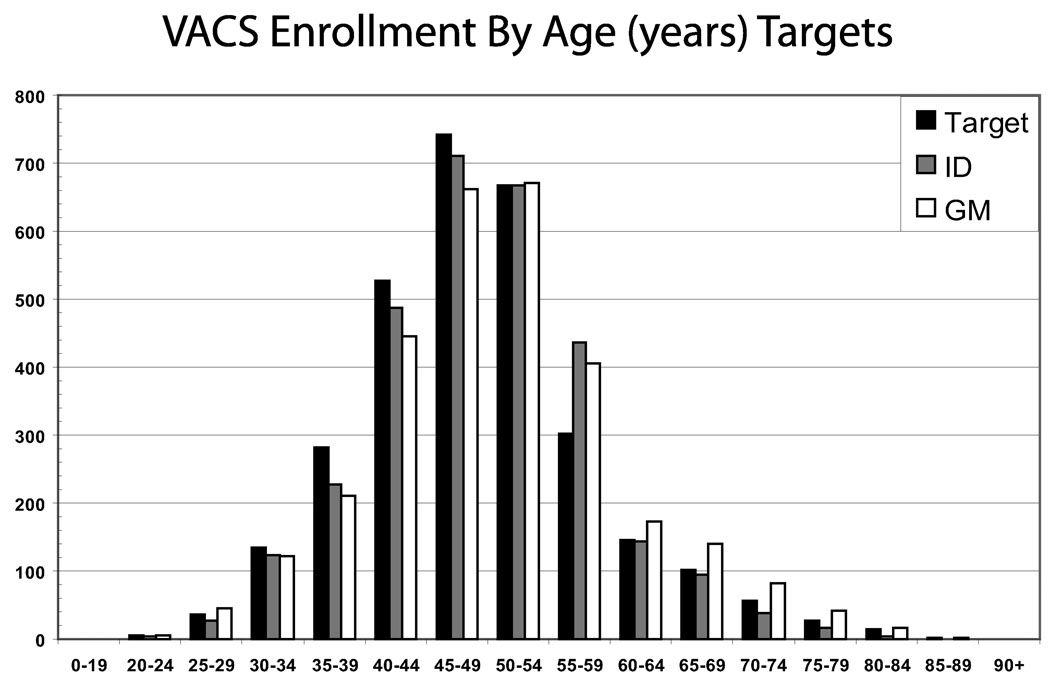

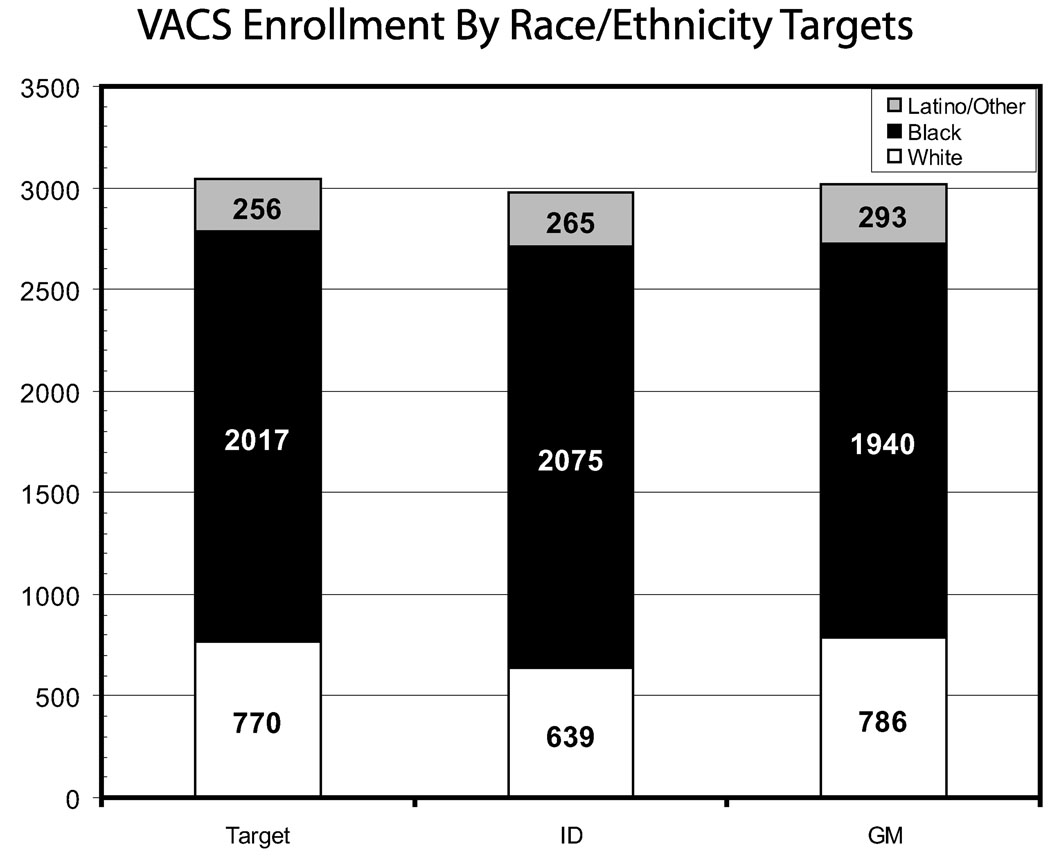

VACS 3 and VACS 5 results have been previously reported. During baseline enrollment 2979 HIV-infected and 3019 age-, race-, and site-matched HIV-uninfected comparators were consented and enrolled in VACS. This represents 99% of the VACS target; 9% of those approached refused and this proportion did not vary by HIV status. Targets for age diversity and racial/ethnic diversity were achieved (Figs. 3 and 4).

FIGURE 3.

VACS enrollment by age (in years) targets.

FIGURE 4.

VACS enrollment by race/ethnicity targets.

When HIV-infected VACS participants are compared with HIV-infected nonparticipants at the same sites and seen during the same time interval, we find that VACS enrolled 58% of all HIV-infected patients seen in these clinics (Table 2). Participants were more likely than nonparticipants to be older (P = 0.0001) and black (70% vs. 49%, P = 0.0001). Although CD4 counts and viral loads were statistically different they were clinically similar. Median CD4 counts (330 vs. 338) viral load counts (1316 vs. 1366). Hospitalization rates were similar and relatively low across the samples. Mortality rates were similar for participants than nonparticipants (3.4 vs. 4.3 deaths/100 person years, P = 0.08) and similar to the national VA HIV mortality rate (3.4 vs. 3.5 deaths/100 person years P = 0.9).

Similar proportions of participants and nonparticipants were started on HAART within 1 year of entering HIV care (75% vs. 76%) and this proportion was somewhat lower than the national VA average of 80% (P = 0.0001). Among those with an initial CD4 cell count less than 200 cells/mm3, the same proportion were on HAART (93% in all cases). The HAART combinations used were similar across these samples, with 88–91% of those receiving HAART receiving either a PI based or NNRTI based regimen.

When VACS participants are compared with national Centers for Disease Control statistics, VACS-enrolled individuals were older (24% vs. 10% >54 years of age, P < 0.0001) and more likely to be black (70% vs. 48%, P < 0.0001). VACS participants were also more likely to be male (96% vs. 75%, P < 0.0001).

Median age for HIV-infected and -uninfected comparators is 49 and 50; 79% and 74% are black and/or Latino/a (Table 3). Both groups were predominantly men (98% vs. 92%). HIV-infected and comparator patients report receiving 72% and 71% of their inpatient care; 74% and 72% of their outpatient care; and 77% and 85% of their mental health care within VA facilities (Table 3), respectively. Of note, HIV patients report that 96% of those receiving antiretroviral therapy get all their antiretroviral medications from the VA pharmacy with an additional 2% reporting some antiretroviral medications from the VA and some from the outside. Only 2% report exclusively getting antiretroviral medications from external sources (data not otherwise shown).

Marital status varied by HIV status. HIV-infected patients were less likely to be married (Table 3, 14% vs. 34%) and more likely to be never married or living with a partner (44% vs. 25%, P < 0.0001). HIV-infected patients were more likely to be unemployed (36% vs. 22%, P < 0.0001). Annual household income is slightly lower in the HIV-infected sample (49% vs. 39% made less than $12,000, P < 0.0001). Educational levels appear similar (P = 0.5) and homelessness was common in both groups (11% vs. 12% were currently homeless; 48% vs. 41% reported being homeless at any time).

Rates of smoking, alcohol use, and illicit drug use are high in both HIV-infected and -uninfected comparators (Table 4). Half the HIV-infected patients (51%) and slightly less than half the controls (41%) reported current cigarette smoking (P < 0.0001). A majority of both groups reported current alcohol consumption (64% and 63%, respectively). A substantial minority reported illicit drug use in the past 12 months (41% of HIV-infected, 27% of HIV-uninfected comparators). The most common illicit drugs of abuse in the past 12 months were marijuana (28% of HIV-infected and 17% of -uninfected subjects) and cocaine (21% of HIV-infected and 14% of those -uninfected subjects).

Underweight (body mass index <20 kg/m2) was more common among HIV-infected patients than comparators (Table 3, 7% vs. 2%). Although 15% of HIV-infected patients were considered obese, 41% of comparators had a body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2 (P < 0.0001). More than half of patients exercise 1 to 4 times per week (51% in both groups). Exercising 5 or more times per week was reported by 18% of HIV-infected and 19% of HIV-uninfected comparators (P = 0.002). SF-12 health-related quality of life scores were low for both HIV-infected veterans and controls (mental component score [MCS]: 33 and 31, respectively; physical component score [PCS]: 42 and 42, respectively).

DISCUSSION

VACS has enrolled a diverse sample of HIV-infected and age–race–site group-matched uninfected comparators. Refusal rates are low and are not different between HIV-infected and -uninfected subjects. In VACS, 77% of the HIV-infected sample and 72% of the -uninfected comparator sample are black and/or Latino/a. Both HIV-infected and -uninfected subjects have a median age near 50 years. Both HIV-infected and -uninfected subjects report receiving most of their outpatient, inpatient, and mental health care from VA facilities (>70% in all cases). Nearly all the HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy fill their prescriptions through the VA pharmacy system (98%).

Veterans in care, whether they are infected by HIV or not, have substantial morbidity. Median SF-12 scores demonstrate substantially depressed values (PCS: 42 and 41 respectively; MCS: 32 and 33). Although these scores are lower than the established standard of 50 for both scores in U.S. populations, they are comparable with the findings of Kazis et al.10 In a national survey of eligible veterans conducted in 1999, Kazis et al found an average PCS of 41 among veterans ages 18–49 years and an average of PCS of 37 among veterans ages 50–64 years. Similarly, Kazis et al found an average MCS of 44 among veterans ages 18–49 years and 50–64 years. Thus, the veterans in our study have higher PCS scores and lower MCS scores than veterans in general indicating better self reported physical functioning, but lower mental health functioning.

Through the use of the ICR and VA administrative data, we are able to describe HIV-infected patients who did not participate in the study but were seen during the same interval at the same sites and eligible for enrollment. This analysis demonstrated that we captured 58% of eligible patients seen in those clinics during this interval. Those enrolled were older, more likely to be black, and somewhat less likely to be on HAART.

This finding underscores the value of following both the prospectively enrolled sample assembled in VACS and described in this report and the Virtual Cohort.41 The prospective sample provides a rich, in-depth look at those currently in long term care for HIV infection and appropriate uninfected comparators. The Virtual Cohort allows us to understand who we have missed and how we might want to weight observations to better represent HIV care within the VA system. It also demonstrated that although we achieved the target enrollment numbers (set at 65% of those in care in fiscal year 2002), the number of patients in these clinics increased from 2002 to 2003–2004 when we enrolled the sample (and achieved a 58% enrollment of all active patients). Thus, VACS is well positioned to compare and contrast the role of alcohol use, comorbidity, and treatment toxicity in determining outcomes among those aging with and without HIV infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

In addition to the authors listed on this report, we would like to thank Kathleen McGinnis, Melissa Skanderson, Kirsha Gordon, and David Reddy for data support; Anne McKeon and Jennifer Rogers for managing and scanning the surveys; and the site coordinators and investigators at each site. Without their invaluable work, this project would not be possible. In addition, we would like to recognize Michael Hall and Angela Consorte for their heroic efforts in organizing the supplement. Most especially, we wish to thank all the veterans who participate in this study and the coordinators who enroll them. Without them, we would have no study.

Primary Funding Sources for VACS: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (U01 AA 13566) and the Veterans Health Administration Office of Research and Development and Public Health Strategic Health Care Group. Primary Funding Source for VACS 5: An Interagency Agreement between National Institute on Aging, National Institute of Mental Health and the Veterans Health Administration Office of Research and Development and Public Health Strategic Health Care Group.

REFERENCES

- 1.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, et al. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smola S, Justice AC, Wagner J, et al. Veterans aging cohort three-site study (VACS 3): overview and description. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(Suppl 1):S61–S76. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00448-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGinnis KA, Justice AC. Factors associated with dementia and cognitive impairments in veterans with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:490. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.3.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyle CA, Decoufle P. National sources of vital status information: extent of coverage and possible selectivity in reporting. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;131:160–168. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher SG, Weber L, Goldberg J, et al. Mortality ascertainment in the veteran population: alternatives to the national death index. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;141:242–250. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Backus L, Mole L, Chang S, et al. The immunology case registry. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54 Suppl 1:S12–S15. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00442-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fusco GP, Justice AC, Becker SL, et al. Strategies for obtaining consistent diagnoses for cause of death in an HIV observational cohort study. XIV International AIDS Conference; July 7–12, 2002; Barcelona, Spain. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braithwaite RS, McGinnis KA, Conigliaro J, et al. A temporal and dose-response association between alcohol consumption and medication adherence among veterans in care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1190–1197. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171937.87731.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kessler R, Wittchen H, Abelson J, et al. Methodological studies of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) in the US National Comorbidity Survey. Int J Methods Psychiatric Res. 1998;7:33–55. [Google Scholar]

- 9a.VHA Health Quality Assessment Project Center for Health Quality, Outcomes and Economic Research Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial Veterans Hospital Bedford Massachusetts. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs Veterans Health Administration Office of Quality and Performance; 2000. Office of Quality Performance Veterans Health Administration Department of Veterans Affairs. Health Status and Outcomes of Veterans: Physical and Mental Component Summary Scores Veterans SF-36 1999 Large Health Survey of Veteran Enrollees Executive Report. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kazis LE, Miller DR, Clark J, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients served by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:626–632. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.6.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control. 1993 Revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. MMWR. 1992;41(RR-17):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordon AJ, Maisto SA, McNeil M, et al. Three questions can detect hazardous drinkers. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:313–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feinn R, Tennen H, Kranzler HR. Psychometric properties of the short index of problems as a measure of recent alcohol-related problems. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1436–1441. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000087582.44674.AF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skinner HA, Horn JL. Alcohol Dependency Scale (ADS): User’s Guide. Toronto: CANADA: Addiction Research Foundation; 1984. pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skinner HA, Allen BA. Alcohol dependence syndrome: measurement and validation. J Abnorm Psychol. 1982;91:199–209. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.91.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller WR, Tonigan JS, Montgomery HA. Assessment of Client Motivation For Change: Preliminary Validation of the SOCRATES Instrument. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biener L, Abrams DB. The Contemplation Ladder: validation of a measure of readiness to consider smoking cessation. Health Psychol. 1991;10:360–365. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.5.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gavin DR, Ross HE, Skinner HA. Diagnostic validity of the drug abuse screening test in the assessment of DSM-III drug disorders. Br J Addict. 1989;84:301–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2005 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Center for Disease Control and Prevention Behavioral Surveillance Working Group. Core Measures for HIV/STD Risk Behavior and Prevention. Sexual Behavior and Drug Behavior Questions. Versions 4 and 5. Atlanta: Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bozzette SA, Berry SH, Duan N, et al. The care of HIV-infected adults in the united states. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1897–1904. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812243392606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21a.Wagner JH, Justice AC, Chesney M, et al. Patient- and provider-reported adherence: toward a clinically useful approach to measuring antiretroviral adherence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54 Suppl 1:S91–S98. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00450-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, et al. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: the AACTG Adherence Instruments. AIDS Care. 2000;12:255–266. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Justice AC, Holmes W, Gifford AL, et al. Development and validation of a self-completed HIV symptom index. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54 Suppl 1:S77–S90. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00449-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Kroenke K, et al. The PRIME-MD 1000 study. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care. JAMA. 1994;272:1749–1756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beck AT, Guth D, Steer RA, et al. Screening for major depression disorders in medical inpatients with the Beck Depression Inventory for Primary Care. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:785–791. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kabacoff RI, Segal DL, Hersen M, et al. Psychometric properties and diagnostic utility of the Beck Anxiety Inventory and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory with older adult psychiatric outpatients. J Anxiety Disord. 1997;11:33–47. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(96)00033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey-Construction of Scales and Preliminary Tests of Reliability and Validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brook RH, Ware JE, Jr, vies-Avery A, et al. Overview of adult health measures fielded in RanD’s health insurance study. Med Care. 1979;17(7 Suppl):iii–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fultz SL, Goulet JL, Weissman S, et al. Differences between infectious diseases-certified physicians and general medicine-certified physicians in the level of comfort with providing primary care to patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:738–743. doi: 10.1086/432621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Leo GI, et al. Reliability of a timeline method: assessing normal drinkers’ reports of recent drinking and a comparative evaluation across several populations. Br J Addiction. 1988;83:393–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1988.tb00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skinner HA, Sheu WJ. Reliability of alcohol use indices. The Lifetime Drinking History and the MAST. J Studies Alcohol. 1982;43:1157–1170. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1982.43.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan AW, Leong FW, Schanley DL, et al. Transferrin and mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase in young adult alcoholics. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1989;23:13–28. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(89)90028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jung K, Pergande M, Rej R, et al. Mitochondrial enzymes in human serum: comparative determinations of glutamate dehydrogenase and mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase in healthy persons and patients with chronic liver diseases. Clin Chem. 1985;31:239–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rej R. Aspartate aminotransferase activity and isoenzyme proportions in human liver tissues. Clin Chem. 1978;24:1971–1979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Justice AC, McGinnis KA, Atkinson JH, et al. Psychiatric and neurocognitive disorders among HIV positive and negative veterans in care: The Veterans Aging Cohort Five-Site Study. AIDS. 2004;18 Suppl 1:S49–S59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lavori PW, Krause-Steinrauf H, Brophy M, et al. Principles, organization, and operation of a DNA bank for clinical trials: a Department of Veterans Affairs cooperative study. Control Clin Trials. 2002;23:222–239. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(02)00193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cowper DC, Hynes DM, Kubal JD, et al. Using administrative databases for outcomes research: select examples from VA Health Services Research and Development. J Med Syst. 1999;23:249–259. doi: 10.1023/a:1020579806511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boyko EJ, Koepsell TD, Gaziano JM, et al. US Department of Veterans Affairs medical care system as a resource to epidemiologists. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:307–314. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown SH, Lincoln MJ, Groen PJ, et al. VistA-US Department of Veterans Affairs national-scale HIS. Int J Medical Informatics. 2003;69:135–156. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(02)00131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cowper DC, Kubal JD, Maynard C, et al. A primer and comparative review of major US mortality databases. Ann Epidemiol. 2002;12:462–468. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00285-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fultz SL, Skanderson M, Mole LA, et al. Development and verification of a “virtual” cohort using the National VA Health Information System. Med Care. 2006;44(Suppl 2):S25–S30. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000223670.00890.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]