Abstract

The nuclear pore complex is the predominant structure in the nuclear envelope that spans the double nuclear membranes of all eukaryotes. Yeasts have one additional organelle that is also embedded in the nuclear envelope: the spindle pole body, which functions as the microtubule organizing center. The only protein known to localize to and be important in the assembly of both of these yeast structures is the integral membrane protein, Ndc1p. However, no homologues of Ndc1p had been characterized in metazoa. Here, we identify and analyze NDC1 homologues that are conserved throughout evolution. We show that the overall topology of these homologues is conserved. Each contains six transmembrane segments in its N-terminal half and has a large soluble C-terminal half of ~300 amino acids. Charge distribution analysis infers that the N- and C-termini are exposed to the cytoplasm. Limited proteolysis of yeast Ndc1p in cellular membranes confirms the orientation of its C-terminus. Although it is not known whether vertebrate NDC1 protein localizes to nuclear pores like its yeast counterpart, the human homologue contains three FG repeats in the C-terminus, a feature of many nuclear pore proteins. Moreover, a small region containing mutations which affect assembly of the nuclear pore in yeast is highly conserved throughout evolution. Lastly, we bring together data from another study to demonstrate that the human homologue of NDC1 is the known inner nuclear membrane protein, NET3.

Keywords: nuclear envelope, nuclear pore, nucleoporin, spindle pole body, pore membrane proteins, NDC1, NET3, topology

INTRODUCTION

Anatomy of the nucleus

The possession of a nucleus distinguishes eukaryotes from prokaryotes. The nucleus not only provides protection for the genome, but also allows spatial and temporal regulation of gene expression. Two nuclear membranes comprise the wall that surrounds the genome, while nuclear pore complexes serve as highly regulated gates orchestrating traffic into and out of the nucleus.

The nuclear membranes consist of an outer nuclear membrane that is contiguous with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) with which it shares many common membrane components. In contrast, the inner nuclear membrane contains a distinctive set of membrane proteins. Unique to metazoa is the presence of a nuclear lamina, a proteinaceous structure composed of intermediate filament-like proteins termed lamins. The nuclear lamina is a key organizational and structural component of the nucleus. Through its filamentous network and associated proteins, the lamina provides structural support and elasticity for the nucleus and acts to position the nuclear pore complexes (for reviews, see Holaska et al., 2002; Hutchison, 2002; Gruenbaum et al., 2005; Hetzer et al., 2005). The lamina is also implicated in DNA replication and transcription. Mutations in lamin genes are associated with an increasing number of muscular degenerative diseases, as well as with the premature aging syndrome progeria (Hutchison, 2002; Mounkes and Stewart, 2004; Pollex and Hegele, 2004; Gruenbaum et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2005). Mutations in inner nuclear membrane proteins often lead to similar types of diseases (Schirmer et al., 2003, Gruenbaum et al., 2005; Hetzer et al., 2005).

Nuclear transport

The outer and the inner nuclear membranes are fused at nuclear pore complexes. These are the only gateways where nucleic acids and proteins can traffic between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Molecules smaller than ~20–40kD can passively diffuse through the nuclear pores. However, trafficking of large macromolecules is mediated by transport receptors and regulated by the small GTPase Ran.

Transport of cellular factors plays an integral role in gene regulation. For example, many transcription factors are restricted to the cytoplasm, until released by a signal which then allows them to translocate into the nucleus to alter gene expression (for review, see Kau et al., 2004). In addition, many viruses need to gain access to the nucleus through the nuclear pores in order to utilize the host’s cellular machinery to replicate their genomes and multiply (for review, see Whittaker et al., 2000).

There are at least 20 nuclear transport receptors in vertebrates and 14 in the budding yeast (for reviews, see Chook and Blobel, 2001; Strom and Weis, 2001; Harel and Forbes, 2004; Pemberton and Paschal, 2005). Depending on function, these receptors are termed importins or exportins, and collectively are called karyopherins. The most well-studied import receptor is importin β. During classical nuclear localization signal (NLS)-mediated import, importin β associates with importin α, an adaptor which recognizes the positively charged NLS present on a cargo protein. A trimeric complex, consisting of importin α, β, and the NLS-containing cargo protein, then translocates through the nuclear pore. The import complex dissociates when it encounters RanGTP in the nucleus, thereby releasing its cargo and completing import. For certain cargos, importin β foregoes the use of importin α and acts alone. A different import receptor, transportin, recognizes a glycine-rich M9 NLS without the use of an adaptor. It too is dissociated from its cargo in the nucleus by RanGTP. Nuclear export receptors, on the other hand, require binding of RanGTP in order to recognize the nuclear export signal on their NES-bearing cargo protein.

The directionality of nuclear transport is determined by the high RanGTP concentration present in the nucleus and low RanGTP concentration in the cytoplasm (for review, see Weis, 2003). This RanGTP gradient is maintained by the exclusive localization of the RanGTP exchange factor, RCC1, on chromatin. The RanGTP activating protein RanGAP and its coactivators, in contrast, concentrate at the cytoplasmic side of the nuclear pores and in the cytoplasm. Although the basics of nuclear transport have been well documented, the precise mechanism of how the transport complex translocates through the nuclear pore is still under debate. At least three hypothetical models of nuclear transport have been proposed and discussed in detail elsewhere (Paschal, 2002; Fahrenkrog and Aebi, 2003; Suntharalingam and Wente, 2003; Weis, 2003; Fahrenkrog et al., 2004; Harel and Forbes, 2004; Peters, 2005, and references therein).

Nuclear pore structure

In order to understand the vital process of nuclear transport, it is essential to know the structure, composition, and mechanism of assembly of the nuclear pore itself. The general structure of the massive nuclear pore is conserved in all eukaryotes, as determined by electron microscopic methods (for reviews, see Rout and Aitchison, 2001; Fahrenkrog and Aebi, 2003). The nuclear pore consists of a large spoke-ring structure, a central channel structure, eight cytoplasmic filaments, and eight nuclear filaments joined at the end to form a “nucleobasket”. Due to the inherent eight-fold symmetry of the nuclear pore, nuclear pore proteins, termed nucleoporins, are present within the pore in multiples of eight (8–48 copies) (Cronshaw et al., 2002). Each vertebrate nuclear pore contains ~30 different proteins to give an overall total of 500–1000 proteins.

To date, only two of the pore proteins are proven to be integral membrane proteins in higher eukaryotes. The remainder are proteins recruited from the cytoplasm to form the bulk of the nuclear pore structure (Cronshaw et al., 2002; for reviews, see Suntharalingam and Wente, 2003; Hetzer et al., 2005; Schwartz, 2005). Approximately a third of the nucleoporins contain phenylalanine-glycine or FG repeats, which are domains that bind transport receptors. The majority of the nucleoporins also contain α-helical repeats and/or β-propeller domains that are thought to provide surfaces or platforms for protein-protein interactions (Schwartz, 2005). The essential and largest vertebrate nuclear pore subcomplex, the Nup107-160 complex, contains nine nucleoporins (Nup160, Nup133, Nup107, Nup96, Nup85, Nup43, Nup37, Seh1, Sec13) (Belgareh et al., 2001; Cronshaw et al., 2002; Harel et al., 2003b; Schuldt, 2003; Walther et al., 2003a; Loiodice et al., 2004). This ‘linchpin’ complex is believed to form a large portion of the central scaffold of the nuclear pore. It may additionally serve to stabilize the curved nuclear membrane encircling the nuclear pores (Devos et al., 2004). Interestingly, alterations in a number of nucleoporins are linked to human genetic and autoimmune diseases (Cronshaw and Matunis, 2003; for review, see Enarson et al., 2004; Kau et al., 2004; Moore, 2005).

Nuclear pore assembly

The mechanism of nuclear pore assembly has not been well elucidated. Nonetheless, we know that nuclear pores assemble at two distinct phases of the cell cycle in higher eukaryotes. First, nuclear pore number doubles in S phase. This requires assembly into the pre-existing intact double nuclear membranes. In addition, the nuclear envelope and nuclear pores entirely disassemble at the onset of mitosis. The nucleoporins dissociate into ten or more individual pore subcomplexes, and the nuclear membranes disassemble into membrane vesicles and retract into the ER (for discussions, see Burke and Ellenberg, 2002; Liu et al., 2003; Hetzer et al., 2005). Reassembly of nuclear pores at the end of mitosis in metazoa can occur by the soluble nucleoporins incorporating into fused nuclear membrane sheets, similar to that of interphase assembly (Macaulay and Forbes, 1996; Harel et al., 2003b). Evidence exists that pore assembly can also be nucleated by nucleoporins binding first to chromatin before the nuclear membranes completely fuse (Burke and Ellenberg, 2002; Walther et al., 2003a; Hetzer et al., 2005). It should be noted that in organisms such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, nuclear pore assembly only occurs in pre-existing fused nuclear membranes since the nuclear envelope in these organisms does not break down at mitosis.

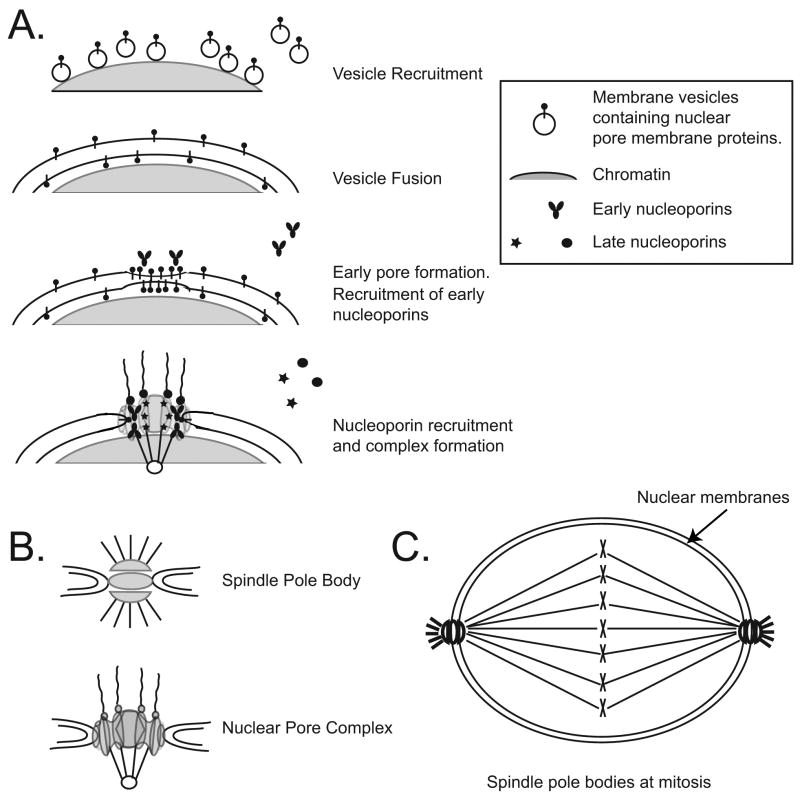

A powerful in vitro system has shed light on the molecular mechanism of nuclear pore assembly. In an extract of Xenopus laevis eggs, when a source of DNA or chromatin is added, it is possible to reconstitute nuclei in vitro that are fully competent for nuclear transport and DNA replication (Lohka and Masui, 1984; Newport, 1987; Macaulay and Forbes, 1996; Wilson and Wiese, 1996). In nuclear assembly in vitro, first membrane vesicles containing integral membrane proteins are recruited and bound to the surface of chromatin (Figure 1A). The membrane vesicles then fuse with one another to form patches of double membrane sheets, where upon nuclear pores are assembled and embedded in the forming double nuclear membranes.

Figure 1. Model of nuclear pore complex assembly.

A. A first step of in vitro nuclear assembly in vertebrates is the recruitment of nuclear envelope vesicle precursors to chromatin. The vesicles then fuse to form double nuclear envelope patches and eventually a closed double nuclear membrane. It is proposed that integral membrane pore proteins are involved in the fusion between the inner and outer nuclear membranes, leading to subsequent formation of the nuclear pore complex. B. The nuclear pore complex (all eukaryotes) and the spindle pole body (yeast) are both embedded in the double nuclear membranes. C. Schematic of the “closed” mitosis of S. cerevisiae. The duplicated spindle pole bodies are on opposite sides of the nuclear membranes and nucleate spindle microtubules.

Distinct regulatory molecules have been implicated to be involved in nuclear pore assembly. RanGTP acts as a positive regulator of nuclear pore assembly, while importin β, in addition to its role in nuclear transport, acts as a negative regulator for both membrane fusion and nuclear pore assembly (Hezter et al., 2000; Harel et al., 2003a; Walther et al., 2003b; for a fuller review, see Harel and Forbes, 2004). The Nup107-160 complex is an early determinant required for vertebrate nuclear pore assembly. Depletion of this complex from the extract leads to a complete lack of assembled nuclear pore structures (Harel et al., 2003b; Walther et al., 2003a). Additionally, in such depleted nuclei, the pore integral membrane proteins are no longer localized in the punctate nuclear rim localization expected of nucleoporins, but instead are distributed diffusely over the surface of nuclei (Harel et al., 2003b).

Additional player(s) in vertebrate nuclear pore assembly?

Nuclear pore membrane proteins have long been thought to participate in nuclear pore assembly (for discussions, see Vasu and Forbes, 2001; Burke and Ellenberg, 2002; Suntharalingam and Wente, 2003). However, it has been difficult to study these membrane proteins, which consist of POM121 and gp210 in vertebrates, and Ndc1p, Pom152p, and Pom34p in the budding yeast S. cerevisiae (Rout et al., 2000; Cronshaw et al., 2002, and references therein). Only recently has vertebrate POM121 been shown to be involved in membrane fusion and nuclear pore assembly (Antonin et al., 2005, and references therein). The role for gp210 remains controversial (Drummond and Wilson, 2002; Antonin et al., 2005). POM121 and gp210, have no known homologues in yeast.

Ndc1p, Pom152p, and Pom34p, conversely, have had no known homologues in higher eukaryotes. Ndc1p (scNdc1p) is the only essential pore membrane protein in yeast. Deletion of Pom152p and/or Pom34p does not appear to have an adverse effect on the viability of the cells (Wozniak et al., 1994; C. Lau and M. Winey, unpublished observations). Interestingly, scNdc1p localizes to both the nuclear pore and the spindle pole body (SPB) (Figure 1B; Chial et al., 1998). Similar to the nuclear pores, the budding yeast spindle pole bodies are also embedded in the nuclear envelope at a site of fusion between the double nuclear membranes (Figure 1B). The SPB in yeast functions to nucleate microtubules and to organize the mitotic spindle (for review, see Jaspersen and Winey, 2004). It duplicates once per cell cycle during G1. The pair of SPBs then migrate to opposite poles during mitosis (Figure 1C). By electron microscopy, the S. cerevisiae SPB appears as disk-like structures (O’Toole et al., 1999).

Of the ~20 different proteins that comprise the budding yeast SPB, three are integral membrane proteins: Ndc1p, Mps2p, and Mps3p. The membrane proteins of the SPB have been implicated to be involved in the insertion of SPB into the double nuclear membranes during SPB duplication. Cells carrying mutations in Ndc1p and Mps2p begin to assemble a partial SPB, but fail to insert it into the nuclear envelope (Winey et al., 1991; Winey et al., 1993; Lau et al., 2004). Certain mutations in Ndc1p also cause defects in nuclear pore assembly (Lau et al., 2004). As nuclear pores and spindle pole bodies are the only large protein structures that span the double nuclear membranes, it is tempting to speculate that their assembly at some level would involve a similar mechanism.

It would be a pleasing symmetry if higher eukaryotes assembled nuclear pores in a comparable manner as in yeast. However, no nuclear pore membrane proteins appear to be common between yeast and metazoa. The only known functional homologue of S. cerevisiae Ndc1p prior to this study was the Cut11+ protein in Schizosaccharomyces pombe, which localizes to SPBs and nuclear pores (West et al., 1998). While Cut11+ is required for SPB duplication, its role at the nuclear pore has yet to be established (West et al., 1998). Despite the essential nature of yeast Ndc1p, its topology remains unknown; thus, models for its involvement in SPB and nuclear pore assembly are limited in detail.

In this study, we identify and analyze metazoan homologues of NDC1, and predict the topology of both yeast and metazoan homologues using charge distribution comparisons. We biochemically determine the yeast Ndc1p topology and examine the sites of mutation in the yeast Ndc1p that cause defects in SPB and nuclear pore assembly for conservation in evolution. Finally, we present evidence that indicates the inner nuclear membrane protein NET3 is the human homologue of yeast Ndc1p.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Finding homologues of S. cerevisiae Ndc1p

The established homologue of NDC1 in S. pombe, Cut11+ (NP_594025), was used to search the genomic database available through the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) with the Position Specific Iterated Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (PSI-BLAST). Once a human homologue (CAI22180) was identified by extensive iterations, it was used to further search the NCBI database for additional homologues using PSI-BLAST.

Multiple Sequence Alignments

All multiple sequence alignments were created using the default parameters of the ClustalW program available through the Workbench program of the San Diego Super Computer Center (workbench.sdsc.edu). The Boxshade program (also available through Workbench) was used to shade identical and similar residues using a similarity threshold fraction of 0.6 or 0.7. AlignX (Invitrogen, Carlsbad CA) was used to manipulate the sequence in Figure 2 to ensure transmembrane regions were properly aligned. Percent identity and similarity among different NDC1 homologues were determined by counting the number of identical and similar residues present in a pairwise alignment using the ClustalW program.

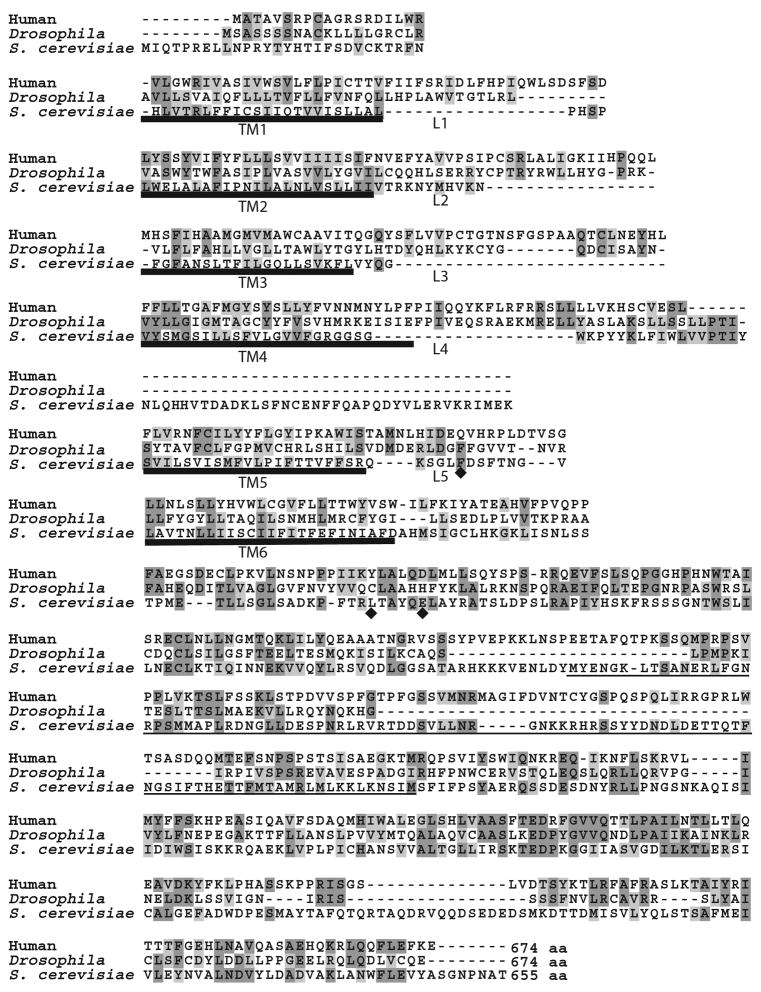

Figure 2. Sequence alignment of NDC1 homologues in human and Drosophila.

A. The sequence of S. cerevisiae Ndc1p (NP_013681) is compared with homologues from Drosophila (NP_651191) and human (CAI22180) using ClustalW. The alignment was manually optimized to ensure proper alignment of transmembrane (TM) segments. Dark gray shading indicates identical amino acids whereas light shading depicts similar amino acids. Bold underline marks the six predicted TM domains. The diamonds denote key mutations found in the S. cerevisiae ndc1–39 allele (F218V, L288M, and E293G) (Lau et al., 2004). The thin underline (amino acids 368–466) highlights the only region found to be non-essential in scNdc1p function by deletion analysis (Lau et al., 2004). Note that this latter region is not well conserved. Numbering corresponds to the scNdc1p sequence.

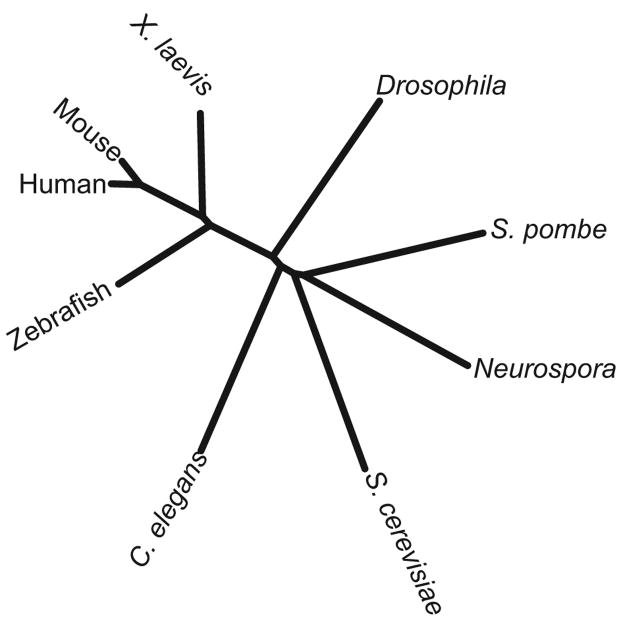

The un-rooted phylogenetic tree was generated in the Workbench program as a dendrogram based on a ClustalW alignment of NDC1 sequences in H. sapiens, M. musculus, X. laevis, D. rerio, C. elegans, D. melanogaster, S. pombe, N. crassa, and S. cerevisiae.

Membrane Topology

The hydropathy plots were generated using the Hidden Markov Model Transmembrane prediction program available through Workbench.

The limited proteolysis assay was done as in Shearer and Hampton (2004). Briefly, yeast microsomes expressing Hmg2p with a myc tag in its fourth lumenal loop (RHY3243), Hmg2p with a myc tag in its cytoplasmically exposed C-terminus (RHY673), or Ndc1p with three myc tags at its C-terminus (Chial et al., 1998) were lysed. The prepared microsomes were then subjected to a light trypsin digestion (250μg/mL) for ten minutes in the presence or absence of 1M Triton X-100. The reactions were loaded on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel and subsequently transferred to a PVDF membrane for one hour at 100V. The blot was probed with the polyclonal anti-c-myc antibody A-14 (Santa Cruz Antibodies, Santa Cruz, CA).

RESULTS

Identification of the metazoan NDC1 homologues

The unique localization of S. cerevisiae Ndc1p (scNdc1p) and S. pombe Cut11+ (S. pombe NDC1) and their implicated function in organelle insertion into the yeast nuclear envelope prompted us to investigate whether they have homologues in other organisms. Despite their similar roles, scNdc1p and S. pombe NDC1 themselves have only limited homology (14% identity, 35% similarity). Starting with the S. pombe NDC1 sequence using iterative PSI-BLAST searches that can reveal even small regions of homology, we were able to identify metazoan NDC1 homologues. Human and Drosophila melanogaster NDC1 homologues are shown in Figure 2; others in Figure 3. Specifically, the scNdc1p (Figure 2) and S. pombe NDC1 proteins are 16% identical and 38%–39% similar to human NDC1 (hNDC1) (Table 1). In turn, Drosophila NDC1 is 19% identical and 44% similar to hNDC1 (Figure 2 and Table 1). A low level of overall sequence homology between yeast and metazoan nucleoporins is in fact very common (Cronshaw et al., 2002; Suntharalingam and Wente, 2003). For example, yeast Nup85p, a member of the Nup107-160 complex, is only 13–14% identical to its metazoan homologues, but serves a highly conserved function (Harel et al., 2003b). Similarly, the yeast Nup133p from the same complex has only 18% identity to a ~360 amino acid region of human Nup133 in the most conserved region of the gene (Vasu et al., 2001). Although homologues between yeast and metazoan nucleoporins rarely share high protein sequence similarity, they are typically similar in size (Vasu and Forbes, 2001). Mirroring this, scNdc1p contains 655 amino acids (Winey et al., 1993), similar in size to the hNDC1 and Drosophila NDC1 with 674 amino acids each (Figure 2).

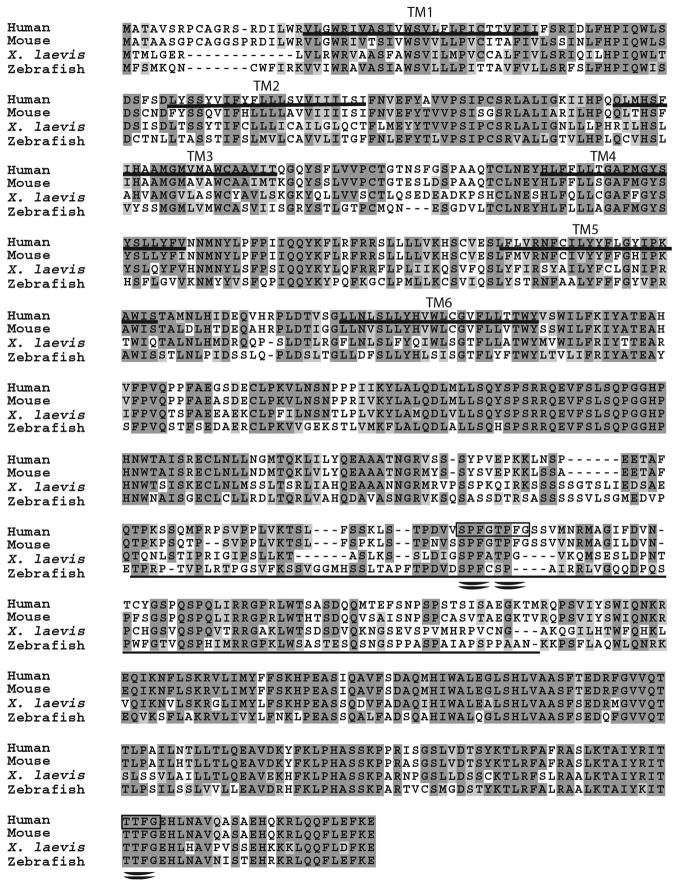

Figure 3. Sequence alignment of NDC1 homologues in vertebrates.

Vertebrate NDC1 homologues are well conserved. The ClustalW multiple alignment program was used to align human (CAI22180), mouse (NP_082631), X. laevis (AAH79784), and zebrafish (AAH53915) NDC1 homologues. Dark gray indicates identical residues while light gray denotes similar residues. Putative TM domains in the human sequence are underlined. The thin underlined region corresponds to the non-essential region found in S. cerevisiae Ndc1p (amino acids 368–466, see also Figure 2). Note that much of this region is not well conserved even among vertebrates. The double underlines and the boxed regions represent FG repeats typically found in nucleoporins.

Table 1.

Sequence comparison of the different NDC1 homologues.

| Species one | Species two | % Identity | % Similarity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human | Mouse | 87 | 92 |

| Human | X. laevis | 54 | 73 |

| Human | Zebrafish | 53 | 75 |

| Human | Drosophila | 19 | 44 |

| Human | S. cerevisiae | 16 | 39 |

| Human | S. pombe | 16 | 38 |

| S. cerevisiae | S. pombe | 14 | 35 |

The PSI-BLAST searches identified NDC1 homologues in multiple vertebrates (Figure 3). These are more closely related to one another: Danio rerio or zebrafish NDC1 bears 53% identity and 75% similarity to human NDC1, while Xenopus laevis NDC1 has 54% identity and 73% similarity to hNDC1 (Figure 3 and Table 1). As expected, mouse NDC1 and hNDC1 are the most similar with 87% identity and 92% similarity (Figure 3 and Table 1). We identified NDC1 homologues in many species including human, mouse, Xenopus laevis, zebrafish, Drosophila, Neurospora, and C. elegans. A phylogenetic tree for NDC1 is shown in Figure 4. After completion of our searches and the experiments reported here, metazoan homologues of NDC1 were also reported by Mans et al. (2004).

Figure 4. NDC1 is conserved in eukaryotes.

Un-rooted phylogenetic tree analysis of NDC1 homologues in human, mouse, X. laevis, D. melanogaster, S. pombe, N. crassa, S. cerevisiae, C. elegans, and D. rerio based on amino acid sequence.

Conserved structure for NDC1 homologues

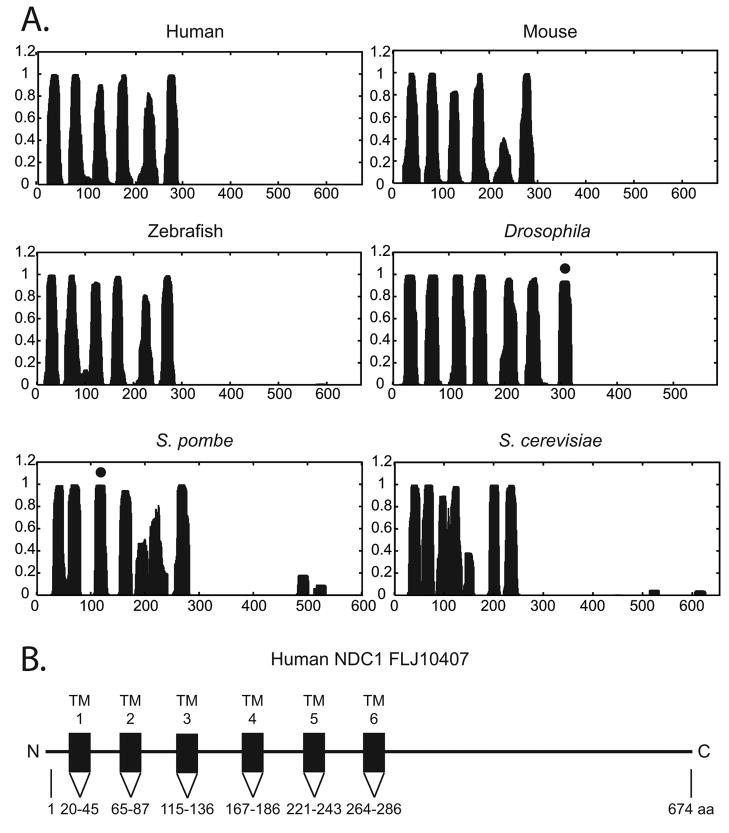

The sequence homology data above indicates the presence of NDC1 homologues in metazoa. Importantly, hydropathy plots predict that all of the NDC1 homologues we identified contain six to seven transmembrane (TM) domains in the N-terminal half of the protein (Figure 5A). TM domains are denoted by bold underlines in Figures 2 and 3. Interestingly, the predicted TM domains (Figure 2, TM 1–6) among human, Drosophila, and yeast are more similar than the loops in the N-terminus half (Figure 2, L1–5). A schematic depicting the hNDC1 structure is shown in Figure 5B. The C-terminal half of the NDC1 homologues is not predicted to contain TM domains, thus is more likely to provide a surface for interaction with other soluble proteins. We conclude that even though the primary sequences can differ substantially, the overall structure of NDC1 is conserved throughout evolution.

Figure 5. NDC1 homologues share similar topological profiles.

A. Human, mouse, zebrafish, Drosophila, S. pombe, and S. cerevisiae protein sequences were analyzed for putative TM domains by the Hidden Markov Model Transmembrane (HMMT) prediction program. The x-axis represents the position of the amino acid while the y-axis represents the probability that amino acid would be found as part of a TM segment. For each protein the N-terminal half consists of six or seven putative TM domains, while the C-terminal half does not contain any TM domains. Those peaks marked with dots in Drosophila and S. pombe are unlikely to be TM domains, as discussed in the text and legend to Figure 6. B. Schematic of the proposed structure of human NDC1 (FLJ10407). Computer predicted TM sequences are represented by black boxes. The figure is not drawn to scale.

The N- and C-termini of NDC1 homologues are predicted to be exposed to the cytoplasm

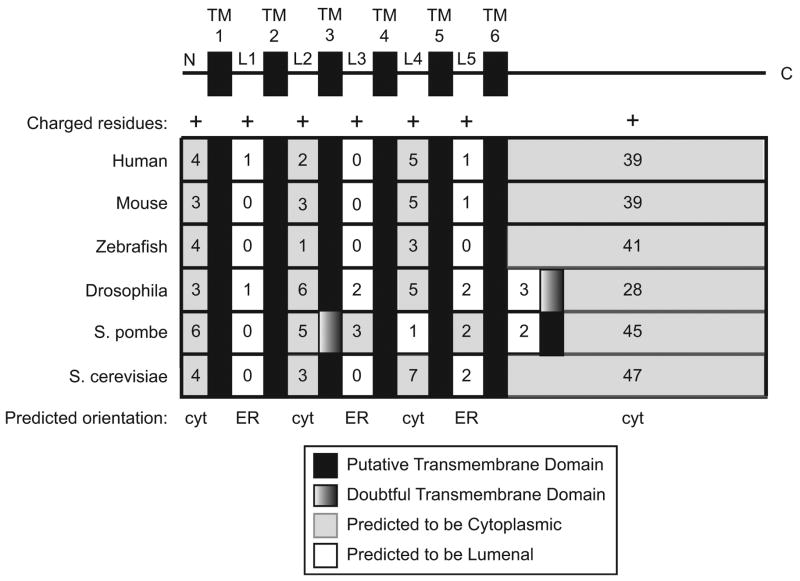

The topology of yeast Ndc1p has never been established. It is not known whether the large C-terminal domain of ~300 amino acids is present in the ER lumen or instead exposed to the cytoplasm. We found in this study from Hidden Markov Model Transmembrane (HMMT) analysis that the scNdc1p contains six TM domains in the N-terminal half (Figure 5A). Although a plausible seventh TM domain was predicted previously from a Kyte-Doolittle hydropathy plot (Winey et al., 1993), we did not observe this with HMMT analysis. To determine the topology of scNdc1p, we used two different strategies: a computational method involving amino acid charge prediction, and a biochemical method of limited proteolysis (Gafvelin et al., 1997; Sakaguchi, 2002; Shearer and Hampton, 2004; Nilsson et al., 2005).

In a multi-pass membrane protein, the orientation of the first transmembrane domain is key to determining the orientation of the rest of the protein. Proteins with a cluster of positively charged amino acids before their first TM domain follow the “positive-inside” rule, so termed because the N-terminus is found inside the cytoplasm (von Heijne, 1989; Gafvelin et al., 1997; Nilsson et al., 2005). Proteins that possess this first TM domain orientation are classified as Signal Anchor Type II proteins; this is the preferred orientation of all the known inner nuclear membrane proteins discovered (Schirmer et al., 2003; Sakaguchi, 2002).

The presence of four lysines and arginines before the first TM domain of scNdc1p suggests that its N-terminus is of this type and is exposed to the cytoplasm (Figure 6). Similar analysis of the human, mouse, zebrafish, Drosophila, and S. pombe NDC1 protein sequences reveals that they also contain a high number of positively charged residues before their first TM domain (Figure 6). Upon further analysis of the regions between TM domains, it is clear that scNdc1p contains a greater number of positively charged amino acids in even-numbered loops (Figure 6, L2 and L4) than in odd-numbered loops (Figure 6, L1, L3, and L5). We conclude that scNdc1p is typical of a multi-pass protein in which positively charged regions or loops are favored in the cytoplasm, whereas loops containing non-charged amino acids are favored in the ER lumen (Nilsson et al., 2005; Gafvelin et al., 1997; Sakaguchi, 2002). It is important to note that domains predicted to be in the cytoplasm can also be in the nucleoplasm. Charge prediction indicates a similar topological organization for the human, mouse, and zebrafish NDC1 homologues, with loops L2 and L4 exposed to the cytoplasm (Figure 6). Specifically, the analysis predicts that budding yeast, human, mouse, and zebrafish NDC1 are all multi-pass Signal Anchor Type II proteins with both N- and C-termini exposed to the cytoplasm.

Figure 6. The N- and C-termini of all NDC1 homologues are predicted to be exposed to the cytoplasm.

Based on TM sequence prediction, the distributions of positively charged amino acids mapping between each TM segment were analyzed. Black boxes denote TM domains predicted by the (HMMT) prediction program. Numbers represent the number of positively charged amino acids present in each intervening loop region. Light gray boxes indicate regions that are predicted to be cytoplasmic while white boxes are predicted to be lumenal. The shaded boxes for Drosophila and S. pombe depict the location of a potential seventh TM domain that was predicted by the HMMT prediction program. However, the positive charge distribution surrounding the third TM domain of S. pombe and the seventh TM domain of Drosophila NDC1 suggests that these TM domains are likely to be “left out” of the membrane (see text), indicating that these NDC1 homologues also have six actual TM domains.

Hydropathy plots had predicted that Drosophila NDC1 and S. pombe NDC1 could possibly contain seven TM domains (Figure 5A). However, by the above charge analysis, we found that there are positive charges present on both sides of the potential seventh TM region of Drosophila NDC1, as well as surrounding the potential third TM region of S. pombe NDC1 (Figure 6, shaded regions; see also Figure 5A, peaks marked by dots). It has been experimentally demonstrated that when a TM domain is spanned by charged regions, the potential TM domain is often not inserted into the membrane but is instead ‘left out’ (Figure 5A, dots; Gafvelin et al., 1997). This results in both of the surrounding charged non-TM regions and the potential TM region they flank remaining in the cytoplasm. Such proteins have been referred to as “frustrated” multi-pass proteins (Gafvelin et al., 1997). If this is the case for Drosophila and S. pombe NDC1, then these “frustrated” multi-pass proteins will, like their homologues, have six actual TM domains with their C-termini exposed to the cytoplasm. In summary, we predict that both the short N-terminus and the large C-terminal half of human, mouse, zebrafish, S. cerevisiae, and likely Drosophila and S. pombe NDC1, are cytoplasmically exposed.

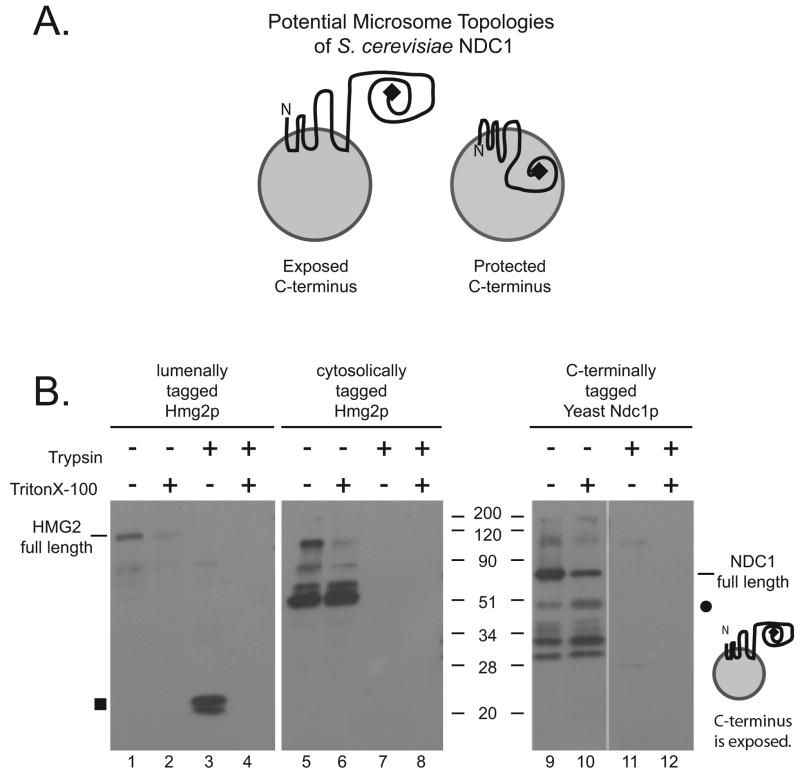

Limited proteolysis indicates a cytoplasmic orientation for the C-terminal half of S. cerevisiae Ndc1p

To test the topology of scNdc1p predicted above, we performed a limited proteolysis assay on yeast microsomes. Microsomes are small membrane vesicles of ER origin, and result when the ER becomes vesiculated by cell lysis. Microsomes are known to accurately retain the orientation of the membrane proteins in the membrane, i.e., the lumen of the ER is equivalent to the lumen of the microsomes (Shearer and Hampton, 2004). We prepared microsomes from a myc-tagged scNdc1p yeast strain and from two control protein strains. Trypsin was added to digest any parts of the proteins exposed to the cytoplasmin vitro (i.e., on the outside of microsomes). Only the TM domains and any parts of the protein in the ER lumen are protected in such an assay. The tagged portion of the protein is detected by Western blotting with an anti-myc antibody. The potential orientations of scNdc1p in microsomes are shown in Figure 7A.

Figure 7. The C-terminus of S. cerevisiae Ndc1p is exposed to the cytoplasm as determined by limited proteolysis.

A. Schematic of two possible orientations of C-terminally myc-tagged Ndc1p in yeast microsomes. The image on the left represents the orientation of the C-terminal myc tag if it were exposed to the cytoplasm, while the image on the right is an example of the C-terminal myc tag if it were protected in the lumen. B. Limited proteolysis assay. Yeast microsomes containing lumenally myc-tagged Hmg2p, cytoplasmically myc-tagged Hmg2p, and C-terminally myc-tagged Ndc1p were subjected to proteolysis with trypsin in the presence and absence of the detergent Triton X-100. Samples were electrophoresed on the same 12% SDS PAGE gel and immunoblotted with anti-myc antibody. As expected the undigested myc-tagged Hmg2p proteins ran at ~100kD. The square on the left indicates the location of the protected myc fragment in the lumenally tagged Hmg2p. As expected the lumenally protected myc fragment is present when lumen myc-Hmg2p is digested with trypsin. It is absent when the myc tag is exposed in the cytosol. Full length myc-tagged Ndc1p is present at 77kD. The circle on the right represents the expected location of the potentially protected (47kD) fragment at the C-terminus of myc-Ndc1p. No band appears in this location suggesting that the C-terminus of scNdc1p is exposed to the cytoplasm. Degradation products that exist in the samples lacking trypsin are likely due to yeast proteases released upon cell lysis. The orientation of the N-terminus could not be determined by such an analysis, because epitope-tagging scNdc1p at the N-terminus renders the cells non-viable (H. Chial and M. Winey, unpublished observations).

A multi-pass Hmg2p protein myc-tagged on its lumenal region indeed showed a protected fragment of ~20kD after trypsin digestion (Figure 7B, lane 3, square). This protected fragment was not detected when the microsomal membranes were solubilized with the Triton X-100 detergent (Figure 7B, lane 4). In contrast, when an Hmg2p protein myc-tagged on a cytosolic region was digested by trypsin treatment, either in the absence or presence of detergent, no protected fragment was detected by Western analysis (Figure 7B, lanes 7 and 8). These controls established the validity of the assay to be used on S. cerevisiae Ndc1p.

Using a strain containing a myc-tag on the C-terminus of scNdc1p, we found that the C-terminal half of scNdc1p was not protected after trypsin digestion (Figure 7B, lane 11). If the C-terminus were lumenal, it should have given an expected fragment of ~45kD, which was not observed (Figure 7B, dot). This result suggests that the C-terminus of scNdc1p is indeed exposed to the cytoplasm, consistent with our amino acid charge prediction (Figure 6).

NET3 is the human homologue of NDC1

Localization of a protein is a key component in the determination of its function. It would be interesting to learn whether human NDC1 localized to the nuclear envelope and nuclear pores. Upon closer examination of the literature, we found that the human NDC1 protein sequence FLJ10407 we obtained by PSI-BLAST (Figure 2) was also identified in a proteomic study as a new nuclear membrane protein (Schirmer et al., 2003). The FLJ10407 sequence codes for a protein the authors named NET3, a nuclear envelope transmembrane protein that fractionates specifically with the nuclear membranes (Schirmer et al., 2003). NET3 epitope tagged at the N-terminus with hemagglutinin (HA) showed colocalization in the region of the lamins (Schirmer et al., 2003). In addition, NET3 was predicted to be an integral membrane protein with its N-terminus in the cytoplasm, since the N-terminal HA tag was retained (Schirmer et al., 2003). The NET3 localization and HA tag retention results are in complete agreement with our study. We identified FLJ10407 to be human NDC1 based on its homology to yeast Ndc1p, which is an integral membrane protein of the yeast nuclear envelope. We also predict hNDC1 contains N- and C-termini that are exposed to the cytoplasm. In conclusion, our sequence analysis indicates that NET3 is hNDC1.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have identified and analyzed the metazoan homologues of the yeast Ndc1p. We demonstrate their homology by sequence analysis and structural domain prediction. Computational and biochemical analysis showed that both the N- and C-termini of the yeast NDC1 are in the cytoplasm. Computational analysis of the metazoan NDC1 homologues agrees with this prediction. Lastly, we believe that the human NDC1 is the equivalent of the nuclear membrane protein, NET3.

Studies in yeast have shown that scNdc1p and S. pombe NDC1 localize to both the spindle pole bodies and the nuclear pores. As yet, we do not know whether metazoan NDC1 proteins localize to nuclear pores and/or centrosomes, the latter being the functional equivalent of the yeast SPBs, albeit not membrane-bound. Interestingly, NDC1 was not recognized as a nucleoporin in a proteomics study on detergent-extracted rat liver nuclei by Cronshaw et al. (2002). Generation of antibodies to metazoan NDC1 proteins will be needed for further analysis. Additionally, immuno-electron microscopy studies will be extremely useful for pinpointing the precise localization of hNDC1/NET3 within the nuclear membranes, i.e., whether it is a nuclear membrane protein or a nuclear pore membrane protein. Strikingly, the vertebrate NDC1 proteins contain several FG regions (SPFG, TPFG, and TTFG) that are characteristic of nucleoporins (Figure 3, double underlines and boxed regions; DF, unpublished observations).

Clues from yeast

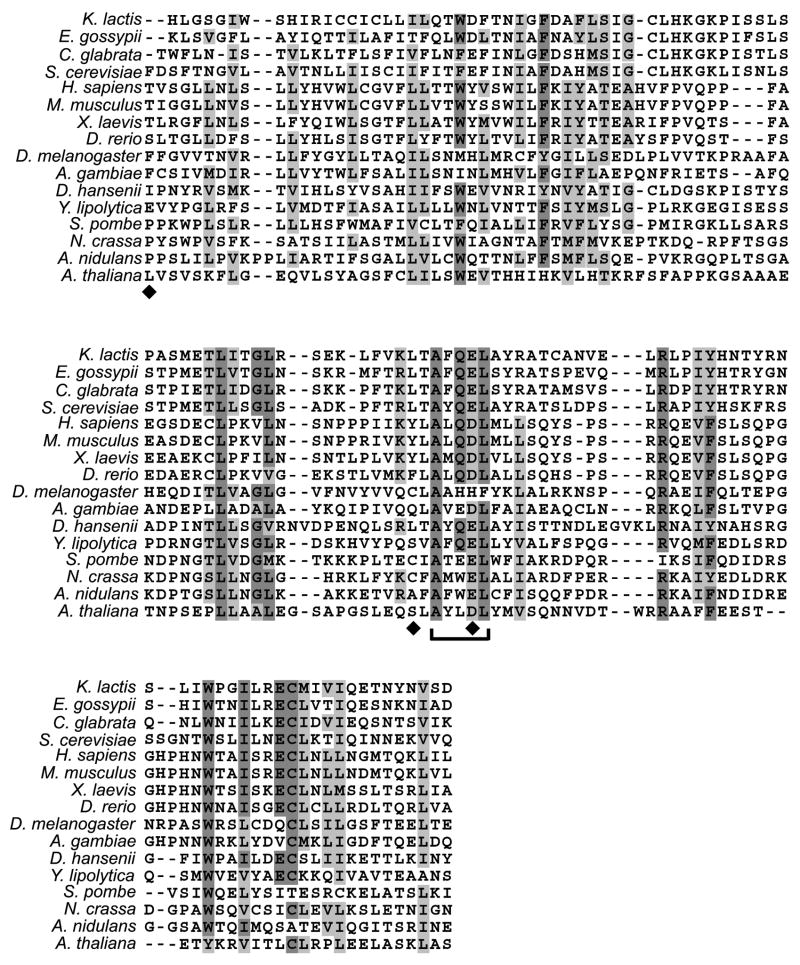

To gain insights into the potential functional domains of metazoan NDC1 protein, we assess the implications from the analysis of yeast genetic studies. Few alleles of scNdc1p exist that disrupt function, primarily because the NDC1 protein is absolutely crucial to successful mitosis. Of these, only the temperature-sensitive mutant, ndc1–39, disrupts assembly of both the spindle pole body and the nuclear pore (Lau et al., 2004). Interestingly, ndc1–39 protein remains localized to the SPBs and the nuclear pores at the restrictive temperature (Lau et al., 2004). This indicates that the mutated regions must not be required for localization of the protein, but instead affect the assembly of the SPB and/or nuclear pores, likely by disrupting interactions between scNdc1p and soluble nucleoporins or other spindle pole body components. The ndc1–39 allele resulted from a PCR mutagenesis and contains six point mutations (Lau et al., 2004). None of the mutations are in the predicted TM domains and three of them are sufficient to cause the temperature-sensitive mutant phenotype (Figures 2 and 8, diamonds; Lau et al., 2004). Mutation E293G falls in a five-residue region (290AXQE/DL294) that is extremely conserved across at least sixteen species from yeast to vertebrates (Figure 8, bracket). The L288M mutation lies immediately adjacent to this region. We predict that this small region is likely to be important for NDC1 function in higher eukaryotes. Other well conserved regions are highlighted in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Region containing essential scNdc1p mutations is conserved throughout evolution.

Sequences of the following sixteen NDC1 homologues were aligned by ClustalW: Kluyveromyces lactis (XP_451609), Eremothecium gossypii (NP_985163), Candida glabrata (XP_446681), S. cerevisiae, H. sapiens, M. musculus, X. laevis, D. rerio, D. melanogaster, Anopheles gambiae (XP_313856), Debaryomyces hansenii (XP_461775), Yarrowia lipolytica (XP_504904), S. pombe, Neurospora crassa, Aspergillus nidulans (XP_408554), and Arabidopsis thaliana (NP_181195). The region corresponding to S. cerevisiae amino acids 218–342 is displayed here. Diamonds indicate the locations of the ndc1–39 mutations (F218V, L288M, and E293G; Lau et al., 2004). The region immediate surrounding the mutation E293G is highly conserved through evolution (bracket).

Indeed, valuable lessons can be learned from studying regions of yeast Ndc1p. Deletion analysis in S. cerevisiae (Lau et al., 2004) showed the only non-essential region of the scNdc1p lies between amino acids 368–466 (Figures 2 and 3, thin underlines). Strikingly, this non-essential region is one of the least conserved regions in vertebrate NDC1 homologues (Figure 3), and largely absent in Drosophila NDC1 (Figure 2). Taken together, our analysis points to important regions in yeast Ndc1p that are conserved in metazoan NDC1 proteins and likely to be essential for their functions, as well as to a region less likely to be essential.

The mechanism by which scNdc1p anchors the SPB and nuclear pores during their assembly is currently not well understood. We speculate that yeast Ndc1p interacts with either soluble or transmembrane nucleoporins via its own cytoplasmic domain. Either or both of these interactions may help initiate the fusion between the outer and inner nuclear membrane and/or to stabilize the fenestra when the two membranes fuse (Figure 9), processes that are required for both spindle pole body and nuclear pore assembly.

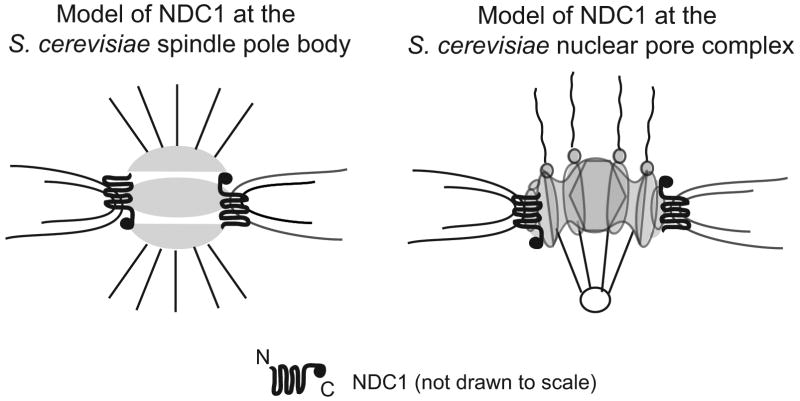

Figure 9. Model of NDC1 location and orientation at the S. cerevisiae spindle pole body and nuclear pore complex.

NDC1 is drawn in a greatly expanded manner to reveal structural topology.

Human NDC1/NET3

hNDC1/NET3 maps to a genetic region that is broadly linked to congenital ptosis, hereditary type 1, a form of muscular dystrophy (Schirmer et al., 2003). Although many other genes reside in this chromosomal location, it will be interesting to characterize the loss-of-function phenotype of the vertebrate NDC1 proteins at the cellular level, as well as at the organismal level.

Further studies will determine whether the metazoan NDC1 is a bone fide member of the nuclear pore. Based on the localization of hNDC1/NET3 to the nuclear envelope (Schirmer et al., 2003), we predict the vertebrate NDC1 proteins carry out similar functions as in yeast. If this is the case, then NDC1 will be the first nuclear pore membrane protein that is conserved throughout evolution, and thus may be the long sought after link between the early membrane fusion events of vertebrate and yeast nuclear pore assembly.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Alexander Shearer and Randy Hampton for technical help and the Hmg2p constructs, Laura Kwinn and Victor Nizet for the use of their AlignX software, and Mark Winey for the scNdc1p construct. The authors were supported by a National Institutes of Health grant R01-GM033279 to D.F.

LITERATURE CITED

- Antonin W, Franz C, Haselmann U, Antony C, Mattaj IW. The integral membrane nucleoporin pom121 functionally links nuclear pore complex assembly and nuclear envelope formation. Mol Cell. 2005;17:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belgareh N, Rabut G, Bai SW, van Overbeek M, Beaudouin J, Daigle N, Zatsepina OV, Pasteau F, Labas V, Fromont-Racine M, Ellenberg J, Doye V. An evolutionarily conserved NPC subcomplex, which redistributes in part to kinetochores in mammalian cells. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:1147–1160. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200101081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke B, Ellenberg J. Remodelling the walls of the nucleus. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:487–497. doi: 10.1038/nrm860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chial HJ, Rout MP, Giddings TH, Jr, Winey M. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ndc1p is a shared component of nuclear pore complexes and spindle pole bodies. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1789–1800. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.7.1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chook YM, Blobel G. Karyopherins and nuclear import. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2001;11:703–715. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(01)00264-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronshaw JM, Krutchinsky AN, Zhang W, Chait BT, Matunis MJ. Proteomic analysis of the mammalian nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:915–927. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200206106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronshaw JM, Matunis MJ. The nuclear pore complex protein ALADIN is mislocalized in triple A syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5823–5827. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1031047100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devos D, Dokudovskaya S, Alber F, Williams R, Chait BT, Sali A, Rout MP. Components of coated vesicles and nuclear pore complexes share a common molecular architecture. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e380. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond SP, Wilson KL. Interference with the cytoplasmic tail of gp210 disrupts “close apposition” of nuclear membranes and blocks nuclear pore dilation. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:53–62. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enarson P, Rattner JB, Ou Y, Miyachi K, Horigome T, Fritzler MJ. Autoantigens of the nuclear pore complex. J Mol Med. 2004;82:423–433. doi: 10.1007/s00109-004-0554-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrenkrog B, Aebi U. The nuclear pore complex: nucleocytoplasmic transport and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;10:757–766. doi: 10.1038/nrm1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrenkrog B, Koser J, Aebi U. The nuclear pore complex: a jack of all trades? Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gafvelin G, Sakaguchi M, Andersson H, von Heijne G. Topological rules for membrane protein assembly in eukaryotic cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6119–6127. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenbaum Y, Margalit A, Goldman RD, Shumaker DK, Wilson KL. The nuclear lamina comes of age. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:21–31. doi: 10.1038/nrm1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harel A, Chan RC, Lachish-Zalait A, Zimmerman E, Elbaum M, Forbes DJ. Importin beta negatively regulates nuclear membrane fusion and nuclear pore complex assembly. Mol Biol Cell. 2003a;14:4387–4396. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-05-0275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harel A, Forbes DJ. Importin beta: conducting a much larger cellular symphony. Mol Cell. 2004;16:319–330. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harel A, Orjalo AV, Vincent T, Lachish-Zalait A, Vasu S, Shah S, Zimmerman E, Elbaum M, Forbes DJ. Removal of a single pore subcomplex results in vertebrate nuclei devoid of nuclear pores. Mol Cell. 2003b;11:853–864. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00116-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetzer M, Bilbao-Cortes D, Walther TC, Gruss OJ, Mattaj IW. GTP hydrolysis by Ran is required for nuclear envelope assembly. Mol Cell. 2000;5:1013–1024. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80266-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetzer MW, Walther TC, Mattaj IW. PUSHING THE ENVELOPE: Structure, Function, and Dynamics of the Nuclear Periphery. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:347–380. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.090704.151152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holaska JM, Wilson KL, Mansharamani M. The nuclear envelope, lamins and nuclear assembly. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:357–364. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00329-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison CJ. Lamins: building blocks or regulators of gene expression? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:848–858. doi: 10.1038/nrm950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaspersen SL, Winey M. The budding yeast spindle pole body: structure, duplication, and function. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.022003.114106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kau TR, Way JC, Silver PA. Nuclear transport and cancer: from mechanism to intervention. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:106–117. doi: 10.1038/nrc1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau CK, Giddings TH, Jr, Winey M. A novel allele of Saccharomyces cerevisiae NDC1 reveals a potential role for the spindle pole body component Ndc1p in nuclear pore assembly. Eukaryot Cell. 2004;3:447–458. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.2.447-458.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Prunuske AJ, Fager AM, Ullman KS. The COPI complex functions in nuclear envelope breakdown and is recruited by the nucleoporin Nup153. Dev Cell. 2003;5:487–498. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00262-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohka MJ, Masui Y. Roles of cytosol and cytoplasmic particles in nuclear envelope assembly and sperm pronuclear formation in cell-free preparations from amphibian eggs. J Cell Biol. 1984;98:1222–1230. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.4.1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loiodice I, Alves A, Rabut G, Van Overbeek M, Ellenberg J, Sibarita JB, Doye V. The entire Nup107–160 complex, including three new members, is targeted as one entity to kinetochores in mitosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:3333–3344. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-12-0878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macaulay C, Forbes DJ. Assembly of the nuclear pore: biochemically distinct steps revealed with NEM, GTP gamma S, and BAPTA. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:5–20. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mans BJ, Anantharaman V, Aravind L, Koonin EV. Comparative genomics, evolution and origins of the nuclear envelope and nuclear pore complex. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:1612–1637. doi: 10.4161/cc.3.12.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore MA. Converging pathways in leukemogenesis and stem cell self-renewal. Exp Hematol. 2005;33:719–737. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mounkes LC, Stewart CL. Aging and nuclear organization: lamins and progeria. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16:322–327. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newport J. Nuclear reconstitution in vitro: stages of assembly around protein-free DNA. Cell. 1987;48:205–217. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90424-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson J, Persson B, von Heijne G. Comparative analysis of amino acid distributions in integral membrane proteins from 107 genomes. Proteins. 2005;60:606–616. doi: 10.1002/prot.20583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole ET, Winey M, McIntosh JR. High-voltage electron tomography of spindle pole bodies and early mitotic spindles in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:2017–2031. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.6.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschal BM. Translocation through the nuclear pore complex. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:593–596. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02227-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pemberton LF, Paschal BM. Mechanisms of receptor-mediated nuclear import and nuclear export. Traffic. 2005;6:187–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters R. Translocation through the nuclear pore complex: selectivity and speed by reduction-of-dimensionality. Traffic. 2005;6:421–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollex RL, Hegele RA. Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Clin Genet. 2004;66:375–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2004.00315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rout MP, Aitchison JD. The nuclear pore complex as a transport machine. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16593–16596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100015200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rout MP, Aitchison JD, Suprapto A, Hjertaas K, Zhao Y, Chait BT. The yeast nuclear pore complex: composition, architecture, and transport mechanism. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:635–651. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.4.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi M. Autonomous and heteronomous positioning of transmembrane segments in multispanning membrane protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;296:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00754-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schirmer EC, Florens L, Guan T, Yates JR, 3rd, Gerace L. Nuclear membrane proteins with potential disease links found by subtractive proteomics. Science. 2003;301:1380–1382. doi: 10.1126/science.1088176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuldt A. Nuclear pore assembly: locating the linchpin. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;6:497. doi: 10.1038/ncb0603-497a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz TU. Modularity within the architecture of the nuclear pore complex. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2005;15:221–226. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearer AG, Hampton RY. Structural control of endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation: effect of chemical chaperones on 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:188–196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307734200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ED, Kudlow BA, Frock RL, Kennedy BK. A-type nuclear lamins, progerias and other degenerative disorders. Mech Ageing Dev. 2005;126:447–460. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strom AC, Weis K. Importin-beta-like nuclear transport receptors. Genome Biol. 2001;2:REVIEWS3008. doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-6-reviews3008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suntharalingam M, Wente SR. Peering through the pore: nuclear pore complex structure, assembly, and function. Dev Cell. 2003;4:775–789. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00162-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasu S, Shah S, Orjalo A, Park M, Fischer WH, Forbes DJ. Novel vertebrate nucleoporins Nup133 and Nup160 play a role in mRNA export. 2001 doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasu SK, Forbes DJ. Nuclear pores and nuclear assembly. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:363–375. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00221-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Heijne G. Control of topology and mode of assembly of a polytopic membrane protein by positively charged residues. Nature. 1989;341:456–458. doi: 10.1038/341456a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther TC, Alves A, Pickersgill H, Loiodice I, Hetzer M, Galy V, Hulsmann BB, Kocher T, Wilm M, Allen T, Mattaj IW, Doye V. The conserved Nup107–160 complex is critical for nuclear pore complex assembly. Cell. 2003a;113:195–206. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther TC, Askjaer P, Gentzel M, Habermann A, Griffiths G, Wilm M, Mattaj IW, Hetzer M. RanGTP mediates nuclear pore complex assembly. Nature. 2003b;424:689–694. doi: 10.1038/nature01898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis K. Regulating access to the genome: nucleocytoplasmic transport throughout the cell cycle. Cell. 2003;112:441–451. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West RR, Vaisberg EV, Ding R, Nurse P, McIntosh JR. cut11+: a gene required for cell cycle-dependent spindle pole body anchoring in the nuclear envelope and biopolar spindle formation in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:2839–2855. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.10.2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker GR, Kann M, Helenius A. Viral entry into the nucleus. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2000;16:627–651. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson KL, Wiese C. Reconstituting the nuclear envelope and endoplasmic reticulum in vitro. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1996;7:487–496. [Google Scholar]

- Winey M, Goetsch L, Baum P, Byers B. MPS1 and MPS2: novel yeast genes defining distinct steps of spindle pole body duplication. J Cell Biol. 1991;114:745–754. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.4.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winey M, Hoyt MA, Chan C, Goetsch L, Botstein D, Byers B. NDC1: a nuclear periphery component required for yeast spindle pole body duplication. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:743–751. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.4.743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak RW, Blobel G, Rout MP. POM152 is an integral protein of the pore membrane domain of the yeast nuclear envelope. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:31–42. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]