Abstract

Thiopurines including 6-thioguanine (SG), 6-mercaptopurine and azathioprine are effective anticancer agents with remarkable success in clinical practice, especially in effective treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). SG is understood to act as a DNA hypomethylating agent in ALL cells, however, the underlying mechanism leading to global cytosine demethylation remains unclear. Here we report that SG treatment results in reactivation of epigenetically silenced genes in T leukemia cells. Bisulfite genomic sequencing revealed that SG treatment universally elicited demethylation in the promoters and/or first exons of the genes that were reactivated. SG treatment also attenuated the expression of histone lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1), thereby stimulating lysine methylation of the DNA methylase DNMT1 and triggering its degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasomal pathway. Taken together, our findings reveal a previously uncharacterized but vital mechanistic link between SG treatment and DNA hypomethylation.

Keywords: 6-Thioguanine, Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Gene expression, DNMT1, lysine-specific demethylase 1

Introduction

In mammalian cells, methylation of DNA at the C5 of cytosine at CpG dinucleotide is one of the major epigenetic modifications that play important roles in embryonic development, gene regulation, cell differentiation, and genomic imprinting (1–2). Aberrant methylation within CpG islands in the genome links to genomic instability and leads to the development of many diseases, including cancer (3–4). Promoter CpG methylation is generally correlated with gene silencing. Previous studies showed that tumor suppressor genes are silenced due to methylation of CpG islands in their promoter regions (5–6). Therefore, promoter cytosine demethylation and the resultant reactivation of silenced genes in cancer cells are feasible approaches to cancer therapy.

DNA methylation in mammalian cells is established and maintained by a family of DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferases (DNMTs) including DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B (7). DNMT1 functions primarily as a maintenance DNA methyltransferase responsible for methylating hemimethylated CpG sites following DNA replication (8–9), whereas DNMT3A and DNMT3B exhibit de novo methyltransferase activity that establishes DNA methylation patterns (10–11). Dysregulation in DNMT1 was thought to play a critical role in cellular transformation (12). Along this line, constitutive over-expression of an exogenous mouse DNMT1 results in a significant increase in global DNA methylation which is accompanied by tumorigenic transformation in NIH 3T3 mouse fibroblasts (13). In contrast, DNMT1 knockouts are resistant to colorectal tumorigenesis (14), and knockdown of DNMT1 by either antisense or siRNA results in demethylation and activation of tumor suppressor genes (15–16). DNMT1 is up-regulated in multiple human cancers (17–18) and previous studies showed that the regulatory regions of tumor suppressor genes are hypermethylated in tumors (19). Therefore, DNMT1 has been proposed as a target for anticancer therapy (12). Indeed, preclinical studies using antisense to DNMT1 have shown inhibition of tumor growth both in vitro (16) and in vivo (20).

Thiopurine drugs, which were first synthesized and investigated by Elion and co-workers (21–22), are widely used as anticancer and immunosuppressive agents and they have achieved remarkable success in clinical practice, especially for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) treatment (23–27). SG is the ultimate active metabolite of all thiopurine prodrugs. It was proposed that SG exerts its cytotoxic effect via its incorporation into DNA, its subsequent methylation by S-adenosyl-L-methionine (S-AdoMet) to render S6-methylthioguanine (S6mG), which directs the misincorporation of dTMP during DNA replication (27). The resulting S6mG:T mispair can trigger the post-replicative mismatch repair (MMR) pathway and futile cycles of repair synthesis may ultimately induce cell death (27). On the other hand, the very low level of conversion of DNA SG to S6mG (<0.02%) in SG-treated leukemia cells and the relatively high mutagenic potential of SG itself suggest that DNA SG may trigger the MMR pathway without being converted to S6mG (28–30). However, the proposed MMR-related mechanism may not be the only pathway for SG to exert its cytotoxic effect during ALL treatment viewing that MMR-deficient ALL cells were also sensitive toward SG (31).

Our recent study showed that the treatment of Jurkat-T cells with SG could lead to a significant decrease in global cytosine methylation (32). Likewise, the level of cytosine methylation in newly synthesized DNA decreased in MOLT-F4 human malignant lymphoblastic cells and HEK-293 T cells upon treatment with SG or 6-MP (33–34). In addition, treatment of HEK-293T cells with SG or 6-MP could elicit a decrease in the enzymatic activity of DNMT1 in the whole cell lysate and a drop in the level of DNMT1 protein (34). However, the mechanism through which the SG induces decreases in DNMT1 protein level and global cytosine methylation remains unclear.

Recent reports revealed that the stability of DNMT1 was regulated by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (35), which involves the methylation of lysine residues in DNMT1 through a dynamic interplay between histone lysine methyltransferase Set7 (36–37) and histone lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1) (37). These studies provided a mechanistic link between DNA and histone methylation systems. Additionally, DNMT1 was found to be rapidly and selectively degraded upon treatment with 5-azacytidine (5-aza-C) or 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (5-aza-CdR) through the ubiquitin-proteasomal pathway (35). Therefore, we reason that the SG-induced decrease in DNMT1 may occur through a similar mechanism. In the present study, we demonstrated that SG could reactivate epigenetically silenced genes in leukemic cells by facilitating proteasome-mediated degradation of DNMT1. In addition, this process involves the down-regulation of LSD1, which established the mechanism underlying the SG-induced hypomethylation in leukemic cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

Jurkat-T, CEM, HEK-293T, and HL-60 cells (ATCC) were cultured under the ATCC-recommended conditions. Jurkat-T and HEK-293T cells were treated with 3 μM SG (Sigma) and/or 25 μM MG132 (Enzo Life Sciences International, Plymouth Meeting, PA), which is a proteasome inhibitor. The whole-cell extracts were prepared by suspending cells in CelLyticTM M (Sigma) lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). Genomic DNA from the cultured cells was isolated by extraction with phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1, v/v) and desalted by ethanol precipitation. Total RNA was extracted from the cultured cells by using RNAeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

HPLC quantification of global cytosine methylation

The level of global cytosine methylation was measured using our previously established method (32). Briefly, genomic DNA (~50 μg) was digested with 2 units of nuclease P1 and 0.008 unit of calf spleen phosphodiesterase in a buffer containing 30 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.5) and 1 mM zinc acetate at 37°C for 4 h. To the digestion mixture were then added 12.5 units of alkaline phosphatase and 0.05 unit of snake venom phosphodiesterase in a 50-mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.6). The digestion was continued at 37°C for 3 h, and the enzymes were removed by chloroform extraction. The amount of nucleosides in the mixture was quantified by UV absorbance measurements. The mixtures were then separated by HPLC on an Agilent 1100 capillary pump (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA) with an Agilent 1100 UV detector monitoring at 260 nm. A 4.6×250 mm Polaris C18 column (5 μm in particle size, Varian Inc., Palo Alto, CA) was used. A solution of 10 mM ammonium formate (pH 4.0, solution A) and a mixture of 10 mM ammonium formate and acetonitrile (70:30, v/v, solution B) were employed as mobile phases. A gradient of 5 min 0–4% B, 45 min 4–30% B and 5 min 30–100% B was used, and the flow rate was 0.80 mL/min. Under these conditions, we were able to resolve 5-methyl-2′-deoxycytidine (5-mdC) from other nucleosides. The global cytosine methylation in cells was quantified based on the peak areas of 5-mdC and 2′-deoxycytidine (dC) with the consideration of the extinction coefficients of the two nucleosides at 260 nm (5020 and 7250 L mol 1 cm 1 for 5-mdC and dC, respectively).

Bisulfite genomic sequencing analysis

Genomic DNA was treated with sodium bisulfite by using EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Orange, CA). Amplified PCR products for RPIB9 (Rap2-binding protein 9), PCDHGA12 (protocadherin-γ subfamily A member 12), DCC (deleted in colorectal cancer) and asparaginase were subcloned using the pGEM-T cloning system (Promega). PCR primers were listed in Table S1. Approximately 15 colonies for each gene were sequenced using an ABI 3730 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR

cDNA was synthesized by using iScriptTM cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) according to the manufacturer’s recommended procedures. Briefly, 1 μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed with 1 μL iScript reverse transcriptase and 4 μL 5×iScript reaction mixture in a 20 μL reaction volume. The reaction was carried out at 25°C for 5 min and at 42°C for 30 min. The reverse transcriptase was then deactivated by heating at 85°C for 5 min.

Quantitative real-time qRT-PCR was performed using iQTM SYBR Green Supermix kit (Bio-Rad) on a Bio-Rad iCycler system (Bio-Rad), and the running conditions were at 95°C for 3 min and 45 cycles at 95°C for 15 s, 56°C for 30 s and 72°C for 45 s. The comparative cycle threshold (Ct) method (ΔΔCt) was used for the relative quanti cation of gene expression (38), and GAPDH gene was used as the internal control. The mRNA level of each gene was normalized to that of the internal control. The primers for real-time PCR were list on Table S2.

RNA interference assay, quantitative real-time RT-PCR and Western blot analysis

LSD1 siRNA (5’-UGAAUUAGCUGAAACACAAUU-3’) and siGENOME Non-Targeting siRNA (D-001210-02-05) were obtained from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO). HEK-293T cells were transfected with 50 nM siRNA along with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s recommended procedures. Briefly, cells were seeded in 6-well plates at 70% confluence (~3×105 cells per well) and transfected with 100 pmol synthetic duplex siRNAs using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent. Cells were incubated for 48 h, after which total RNA and cellular extracts were prepared. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was conducted using the same procedures as described above. Primer sequences used for RT-PCR were shown in Table S2, and GAPDH was used as an internal control. Cell extracts were subjected to Western blot analysis; antibodies that specifically recognized human DNMT1 (New England Biolabs), DNMT1-K142me (36), LSD1 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), β-actin (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) were used at 1:3000, 1:1000, 1:10,000 and 1:10,000 dilutions, respectively. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary goat anti-rabbit antibody (Abcam) was used at a 1:10,000 dilution.

Results

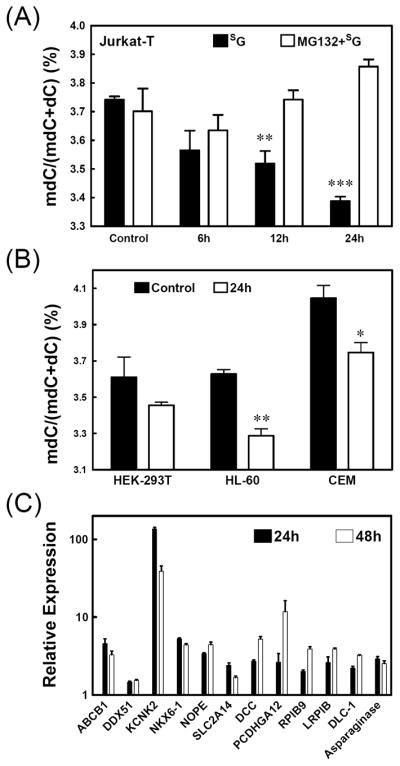

SG treatment leads to decrease in global cytosine methylation in cultured human cells

Thiopurine drugs have been successfully employed for treating acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) (27) and a number of genes in bone marrow leukocytes from ALL patients and in two ALL cell lines (Jurkat-T and NALM-6) were found to be epigenetically silenced (39). Viewing that the mean peak concentration of SG in plasma of ALL patients was 0.52 ± 0.72 μM after oral SG administration (60 mg/m2) and 2.7 ± 1.4 μM after continuous intravenous infusion (20 mg/m2/h) (40), we treated Jurkat-T cells with 3 μM SG from 6 to 24 h and assessed the level of global cytosine methylation by using an HPLC method (Figure S1 shows a typical HPLC trace for monitoring the global cytosine methylation) (32). It turned out that treatment with 3 μM SG for 6 and 24 h led to appreciable decreases in global cytosine methylation in Jurkat-T cells, i.e., the percentage of cytosine methylation dropped from 3.74 ± 0.02% in untreated cells to 3.57 ± 0.12%, 3.52 ± 0.08% and 3.34 ± 0.03% in cells treated with 3 μM of SG for 6, 12 and 24 h, respectively (Figure 1A). Likewise, SG exposure could lead to loss in global cytosine methylation in other human cell lines. In this regard, treatment of HEK-293T, HL-60 and CEM cells with 3 μM of SG for 24 h resulted in decreases in cytosine methylation from 3.61 ± 0.16%, 3.63 ± 0.04% and 4.05 ± 0.14% to 3.46 ± 0.03%, 3.29 ± 0.07%, and 3.75 ± 0.11%, respectively (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. SG treatment results in decreased global cytosine methylation and increased expression of epigenetically silenced genes in human cells.

(A) The percentages of global cytosine methylation in genomic DNA isolated from Jurkat-T cells that were either treated with SG alone or pretreated with MG132 (25 μM) for 2 h and then treated with SG (3 μM) for the indicated time periods. (B) The percentages of global cytosine methylation in genomic DNA isolated from HEK-293T, HL-60 and CEM cells that were untreated or treated with SG (3 μM) for the time periods indicated. (C) Change in mRNA expression in Jurkat-T cells following treatment with SG for 24 h (white bar) or 48 h (black bar). The data represent the means and standard deviations of results from three independent drug treatments. The paired t-test was performed to evaluate the difference between control samples and treated samples in (A) and (B) (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

SG treatment resulted in the reactivation of genes silenced in ALL cells

Previous large-scale CpG methylation analysis revealed that the promoter regions of 11 genes were aberrantly methylated in primary leukocytes from ALL patients and in cultured ALL cells (39). To determine whether the SG-induced global cytosine hypomethylation can reactivate the expression of these genes, we examined, by using quantitative real-time RT-PCR, the mRNA levels of these genes in Jurkat-T cells before and after SG treatment. It turned out that mRNA expression levels of all these genes increased in Jurkat-T cells after SG treatment (Figure 1C). For instance, there were more than 4-fold increases in mRNA levels of DCC, KCNK2, LRP1B, NKX6-1, NOPE, PCDHGA12 and RPIB9 genes after treatment with SG for 48 h.

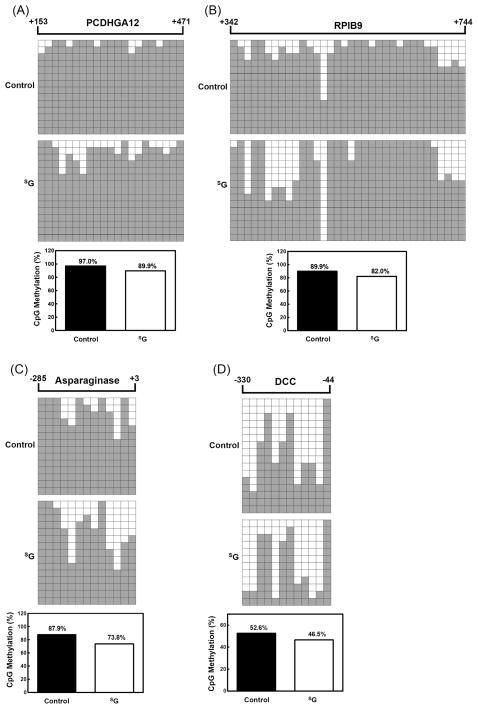

SG induced cytosine demethylation in promoter and/or the first exon of genes silenced in ALL cells

To gain insights into the mechanisms responsible for the reactivation of the silenced genes upon SG treatment, we performed bisulfite genomic sequencing of the first exon of PCDHGA12 gene, the predicted promoter and the first exon of RPIB9 gene, and the predicted promoters of the asparaginase and DCC genes in Jurkat-T cells (Figure 2). These regions were chosen because the methylation status of the promoter and the first exon of genes are important for the epigenetic regulation of gene expression (5, 39) and the expression levels of these genes were substantially elevated after SG treatment (Figure 1C). Consistent with the global cytosine methylation and quantitative real-time RT-PCR results, the methylation level in the promoter and/or first exon of these examined genes dropped by 7–16% upon SG treatment, suggesting that SG could induce the demethylation in the predicted promoter and/or the first exon of genes thereby stimulating the expression of these genes.

Figure 2. Bisulfite genomic sequencing shows that SG treatment leads to decreased methylation at CpG sites in the predicted promoter region and/or the first exon of genes.

(A) PCDHGA12; (B) RPIB9; (C) Asparaginase; (D) DCC. Each square represents a single CpG site. The number of rows designates the number of the colonies sequenced. White and black squares represent unmethylated and methylated CpGs, respectively. The percentage of CpG methylation is listed underneath each figure.

SG treatment led to the proteasomal degradation of DNMT1

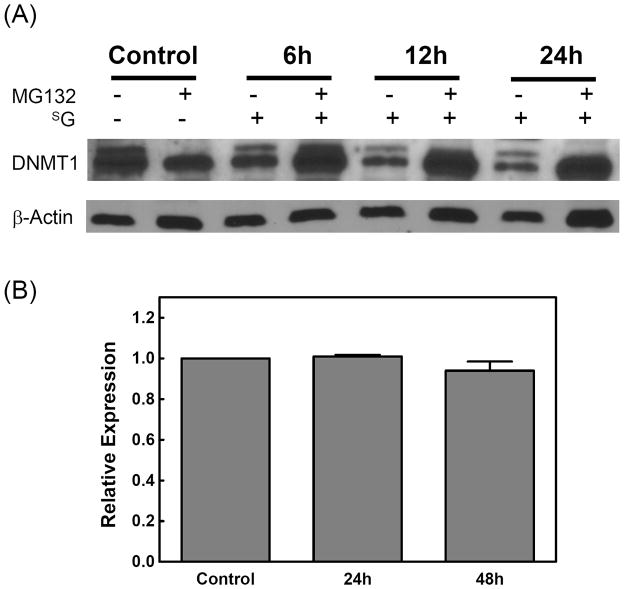

To further explore the molecular mechanism underlying the SG-induced cytosine demethylation, we determined the protein levels of DNMT1 in the extracts of cells treated with SG for various time periods since DNMT1 is the major maintenance cytosine methyltransferase in mammalian cells. Immunoblot analysis of cell extract indeed revealed a time-dependent decrease in DNMT1 level following SG treatment (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. DNMT1 was degraded upon SG treatment and the degradation could be blocked by a proteasomal inhibitor.

(A) Western blot analysis of DNMT1 with whole-cell extracts from Jurkat-T cells treated with SG (3 μM) alone or pretreated with MG132 (25 μM) for 2 h and then treated with SG for the indicated time periods. β-actin was used as a loading control. (B) Expression of DNMT1 mRNA is not reduced in cells treated with SG. The mRNA level of DNMT1 in Jurkat-T cells treated with SG (3 μM) for 24 or 48 h was analyzed by real-time RT-PCR. The bar diagram shows the fold change in the mRNA level of DNMT1. The results represent the means and standard deviations of data from three independent experiments.

To determine whether the drop in DNMT1 level was due to the down-regulation of its transcription, we measured the mRNA level of DNMT1 by real-time RT-PCR (Figure 3B). Upon treatment with 3 μM SG, the DNMT1 transcript level was similar to that of the control cells (Figure 3B). Thus, the SG-induced decrease in DNMT1 protein level was not due to a decline in its mRNA level.

A previous report showed that DNMT1 could be rapidly degraded upon 5-aza-CdR treatment through the ubiquitin-proteasomal pathway (35). We reasoned that the SG-induced DNMT1 degradation might also occur through the same pathway. If this is the case, the drug-elicited DNMT1 degradation should be rescued by pre-treating the cells with a proteasome inhibitor. It turned out that treatment of cells with proteasome inhibitor MG132 indeed restored the percentage of global cytosine methylation (Figure 1A) and abolished the SG-mediated decrease in DNMT1 protein level (Figure 3A), supporting that the SG-induced degradation of DNMT1 involved the proteasomal pathway.

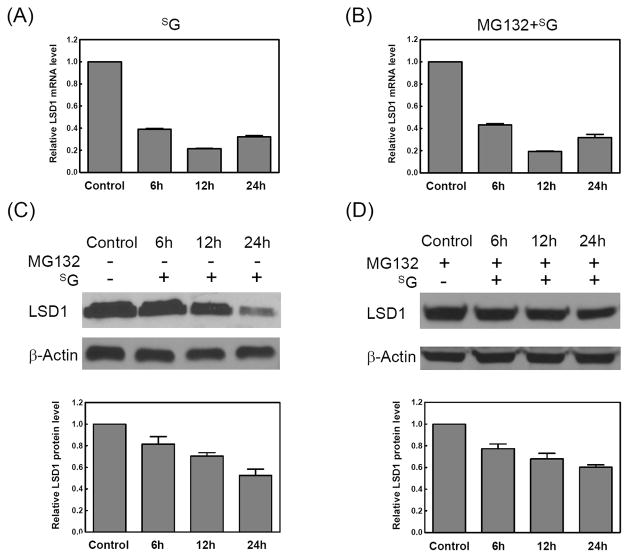

SG could induce the down-regulation of LSD1 and the increase in lysine methylation in DNMT1

Recent studies revealed that the stability of DNMT1 protein was dynamically regulated by its methylation on lysine residues via histone lysine methyltransferase Set7 (36–37) and histone lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1) (37). Thus, we further investigated whether the SG-mediated degradation of DNMT1 involved the alteration in the protein level of Set7 and/or LSD1. It turned out that the treatment of Jurkat-T cells with SG led to a decrease in LSD1 at both the mRNA and protein levels (Figure 4A and 4C); the SG-induced down-regulation of LSD1 in Jurkat-T cells was not restored by MG132 at either mRNA or protein level (Figure 4B and 4D), which pointed to the transcriptional regulation of LSD1. However, there was no apparent alteration in Set7 level in Jurkat-T cells treated with SG (Figure S2). In addition, siRNA knockdown of LSD1 in HEK-293T cells (Figure S3) induced the degradation of DNMT1 as did SG (Figure S4 A and B), revealing that SG may trigger DNMT1 degradation via diminishing the LSD1 expression.

Figure 4. LSD1 was degraded upon SG treatment.

(A) Real-time RT-PCR analysis of the expression of LSD1 mRNA in cells treated with SG for various time periods. (B) Real-time RT-PCR analysis of the expression of LSD1 mRNA in cells pretreated with MG132 (25 μM) for 2 h and then treated with SG (3 μM) for various time periods. The results represent the means and standard deviations of data from three independent experiments. (C) Western blot analysis of LSD1 with whole-cell extracts from Jurkat-T cells treated with SG (3 μM) for various time periods. (D) Western blot analysis of LSD1 with whole-cell extracts from Jurkat-T cells pretreated with MG132 (25 μM) for 2 h and then treated with SG for various time periods. The histograms shown under (C) and (D) are the LSD1 fold changes, which were obtained by normalizing the band intensity of LSD1 to that of the loading control, β-actin. The results represent the means and standard deviations of data from three independent drug treatment and Western blot experiments.

It was reported that K142 was a major site responsible for the regulation of DNMT1 stability (36). Next, we assessed whether SG treatment could result in the alteration of K142 methylation in DNMT1. Immunoblot results showed that there was no significant change in K142-methylated DNMT1 in Jurkat-T or HEK-293T cells upon treatment with SG (Figure S5 and Figure S4C). However, the total amount of DNMT1 protein decreased markedly upon SG treatment (Figure 3A), suggesting that the percentage of K142-methylated DNMT1 increased upon SG treatment. In addition, the methylated DNMT1 protein was rapidly degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, which may account for the lack of accumulation of the methylated DNMT1 upon SG treatment. In this vein, it was found that the methylated DNMT1 had a much shorter half-life (2–6 h) than its unmethylated counterpart (12–24 h) (36). Taken together, our results demonstrated that SG could decrease the expression of LSD1, which led to enhanced lysine methylation in DNMT1 and its subsequent degradation via the proteasomal pathway.

Discussion

We investigated the epigenetic effect of SG and discovered a novel mechanism underlying the SG-induced global cytosine demethylation in ALL cells. Our results demonstrated that SG exerted its epigenetic effect by downregulating the expression of LSD1, thereby enhancing the lysine methylation level in DNMT1 and triggering its degradation via the proteasomal pathway. The diminished DNMT1 expression led to subsequent promoter demethylation and reactivation of epigenetically silenced genes in ALL cells.

Treatment of Jurkat-T cells with SG resulted in elevated expression of 12 genes, 11 of which were previously shown to be epigenetically silenced in primary ALL cells and two ALL cell lines (39). Although the explicit roles of these genes in the pathobiology of ALL remain unclear, the epigenetically silenced state of these genes in ALL cells and their reactivation upon SG treatment suggest that these genes might serve as important molecular targets for ALL treatment and act as biomarkers for monitoring the efficacy of ALL treatment. ABCB1, RPIB9 and PCDHGA12 have functions that may be associated with patient response to ALL chemotherapy (41–42). DCC, DLC-1 and LRP1B were identified as tumor suppressor genes and were aberrantly methylated in cancer cells (43–45). Bisulfite sequencing analysis revealed the drug-induced demethylation in the putative promoter and/or the first exon of DCC, asparaginase, RPIB9, and PCDHGA12 genes, which provided insights into the mechanisms accounting for the elevated mRNA expression of these genes in Jurkat-T cells after SG treatment.

An interesting observation is that the expression level of the asparaginase gene was increased upon SG treatment. Different from normal cells, ALL cells are unable to synthesize the non-essential amino acid asparagine (46); thus, the survival of leukemic cells depends on circulating asparagine. This forms the basis of using E. coli asparaginase in the clinical treatment of ALL (46–47), where the enzyme catalyzes the decomposition of L-asparagine to L-aspartic acid and ammonia. In current protocols of ALL treatment, asparaginase, along with other drugs, are often used in the remission-induction phase, whereas methotrexate plus mercaptopurine are frequently used in consolidation treatment (48). Our real-time PCR results showed a 3-fold increase in asparaginase expression upon SG treatment at 24 h, which may further deprives the leukemic cells of asparagine and contributes to the killing of residual leukemic cells during the consolidation treatment. Thus, our results underscored a potentially new pathway contributing to the antileukemic effect of SG. It is important to investigate in the future whether the same finding can be made for ALL patients administered with the thiopurine drug.

It has been recently demonstrated that LSD1 was able to demethylate and stabilize DNMT1 protein from its degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (37). By using metabolic labeling method, the authors found that the methylation level of DNMT1 was markedly increased in Aof21lox/1lox (LSD1-deficient) cells when compared to Aof22lox/+ (LSD1-proficient) cells (37). These results underscored enhanced methylation of DNMT1 protein in the absence of LSD1, suggesting that DNMT1 is susceptible to LSD1-mediated lysine demethylation in vivo. The stability of DNMT1 was also regulated by the histone methyltransferase activity of Set7 through the methylation of DNMT1 at K142 (36). In the current study, we found that LSD1 was decreased at both the mRNA and protein level, but there was no significant change in Set7 level upon SG treatment, revealing that the diminished expression of LSD1 may lead to enhanced DNMT1 methylation. The methylated DNMT1 can then be subjected to degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Taken together, this study offers a rational explanation for the demethylation in DNA and reactivation of silenced genes by SG and underscores a new epigenetic effect of SG on leukemia treatment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 DK082779).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

B. Y., J. Z., H. X., S.J., S. P. and Y. W. designed research and wrote the paper; B. Y., J. Z., H. X., L. X., Q. C. and T. W. performed research.

References

- 1.Jaenisch R, Bird A. Epigenetic regulation of gene expression: how the genome integrates intrinsic and environmental signals. Nat Genet. 2003;33:245–54. doi: 10.1038/ng1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bird A. DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes Dev. 2002;16:6–21. doi: 10.1101/gad.947102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scarano MI, Strazzullo M, Matarazzo MR, D'Esposito M. DNA methylation 40 years later: Its role in human health and disease. J Cell Physiol. 2005;204:21–35. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robertson KD. DNA methylation and human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:597–610. doi: 10.1038/nrg1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herman JG, Baylin SB. Gene silencing in cancer in association with promoter hypermethylation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2042–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra023075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costello JF, Fruhwald MC, Smiraglia DJ, Rush LJ, Robertson GP, Gao X, et al. Aberrant CpG-island methylation has non-random and tumour-type-specific patterns. Nat Genet. 2000;24:132–8. doi: 10.1038/72785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goll MG, Bestor TH. Eukaryotic cytosine methyltransferases. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:481–514. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.010904.153721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bestor TH. Activation of mammalian DNA methyltransferase by cleavage of a Zn binding regulatory domain. EMBO J. 1992;11:2611–7. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leonhardt H, Page AW, Weier HU, Bestor TH. A targeting sequence directs DNA methyltransferase to sites of DNA replication in mammalian nuclei. Cell. 1992;71:865–73. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90561-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okano M, Bell DW, Haber DA, Li E. DNA methyltransferases Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b are essential for de novo methylation and mammalian development. Cell. 1999;99:247–57. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81656-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okano M, Xie S, Li E. Cloning and characterization of a family of novel mammalian DNA (cytosine-5) methyltransferases. Nat Genet. 1998;19:219–20. doi: 10.1038/890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szyf M. DNA methylation properties: consequences for pharmacology. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1994;15:233–8. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(94)90317-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu J, Issa JP, Herman J, Bassett DE, Jr, Nelkin BD, Baylin SB. Expression of an exogenous eukaryotic DNA methyltransferase gene induces transformation of NIH 3T3 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:8891–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.8891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laird PW, Jackson-Grusby L, Fazeli A, Dickinson SL, Jung WE, Li E, et al. Suppression of intestinal neoplasia by DNA hypomethylation. Cell. 1995;81:197–205. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90329-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Przybylski M, Kozlowska A, Pietkiewicz PP, Lutkowska A, Lianeri M, Jagodzinski PP. Increased CXCR4 expression in AsPC1 pancreatic carcinoma cells with RNA interference-mediated knockdown of DNMT1 and DNMT3B. Biomed Pharmacother. 2010;64:254–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fournel M, Sapieha P, Beaulieu N, Besterman JM, MacLeod AR. Down-regulation of human DNA-(cytosine-5) methyltransferase induces cell cycle regulators p16(ink4A) and p21(WAF/Cip1) by distinct mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:24250–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.24250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Issa JP, Vertino PM, Wu J, Sazawal S, Celano P, Nelkin BD, et al. Increased cytosine DNA-methyltransferase activity during colon cancer progression. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:1235–40. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.15.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robertson KD, Uzvolgyi E, Liang G, Talmadge C, Sumegi J, Gonzales FA, et al. The human DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) 1, 3a and 3b: coordinate mRNA expression in normal tissues and overexpression in tumors. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:2291–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.11.2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baylin SB, Esteller M, Rountree MR, Bachman KE, Schuebel K, Herman JG. Aberrant patterns of DNA methylation, chromatin formation and gene expression in cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:687–92. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.7.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramchandani S, MacLeod AR, Pinard M, von Hofe E, Szyf M. Inhibition of tumorigenesis by a cytosine-DNA, methyltransferase, antisense oligodeoxynucleotide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:684–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elion GB. Symposium on immunosuppressive drugs. Biochemistry and pharmacology of purine analogues. Fed Proc. 1967;26:898–904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elion GB. The purine path to chemotherapy. Science. 1989;244:41–7. doi: 10.1126/science.2649979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burchenal JH, Murphy ML, Ellison RR, Sykes MP, Tan TC, Leone LA, et al. Clinical evaluation of a new antimetabolite, 6-mercaptopurine, in the treatment of leukemia and allied diseases. Blood. 1953;8:965–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murray JE, Merrill JP, Harrison JH, Wilson RE, Dammin GJ. Prolonged survival of human-kidney homografts by immunosuppressive drug therapy. N Engl J Med. 1963;268:1315–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196306132682401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lennard L. The clinical pharmacology of 6-mercaptopurine. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1992;43:329–39. doi: 10.1007/BF02220605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bertino JR. Improving the curability of acute leukemia: pharmacologic approaches. Semin Hematol. 1991;28:9–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karran P, Attard N. Thiopurines in current medical practice: molecular mechanisms and contributions to therapy-related cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:24–36. doi: 10.1038/nrc2292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yuan B, O’Connor TR, Wang Y. 6-Thioguanine and S6-Methylthioguanine Are Mutagenic in Human Cells. ACS Chem Biol. 2010;5:1021–7. doi: 10.1021/cb100214b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang H, Wang Y. LC-MS/MS coupled with stable isotope dilution method for the quantification of 6-thioguanine and S6-methylthioguanine in genomic DNA of human cancer cells treated with 6-thioguanine. Anal Chem. 2010;82:5797–803. doi: 10.1021/ac1008628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yuan B, Wang Y. Mutagenic and cytotoxic properties of 6-thioguanine, S6-methylthioguanine, and guanine-S6-sulfonic acid. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:23665–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804047200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krynetski EY, Krynetskaia NF, Gallo AE, Murti KG, Evans WE. A novel protein complex distinct from mismatch repair binds thioguanylated DNA. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:367–74. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.2.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang H, Wang Y. 6-Thioguanine perturbs cytosine methylation at the CpG dinucleotide site by DNA methyltransferases in vitro and acts as a DNA demethylating agent in vivo. Biochemistry. 2009;48:2290–9. doi: 10.1021/bi801467z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lambooy LH, Leegwater PA, van den Heuvel LP, Bokkerink JP, De Abreu RA. Inhibition of DNA methylation in malignant MOLT F4 lymphoblasts by 6-mercaptopurine. Clin Chem. 1998;44:556–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hogarth LA, Redfern CP, Teodoridis JM, Hall AG, Anderson H, Case MC, et al. The effect of thiopurine drugs on DNA methylation in relation to TPMT expression. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;76:1024–35. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghoshal K, Datta J, Majumder S, Bai S, Kutay H, Motiwala T, et al. 5-Aza-deoxycytidine induces selective degradation of DNA methyltransferase 1 by a proteasomal pathway that requires the KEN box, bromo-adjacent homology domain, and nuclear localization signal. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:4727–41. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.11.4727-4741.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 36.Esteve PO, Chin HG, Benner J, Feehery GR, Samaranayake M, Horwitz GA, et al. Regulation of DNMT1 stability through SET7-mediated lysine methylation in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:5076–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810362106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang J, Hevi S, Kurash JK, Lei H, Gay F, Bajko J, et al. The lysine demethylase LSD1 (KDM1) is required for maintenance of global DNA methylation. Nat Genet. 2009;41:125–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taylor KH, Pena-Hernandez KE, Davis JW, Arthur GL, Duff DJ, Shi H, et al. Large-scale CpG methylation analysis identifies novel candidate genes and reveals methylation hotspots in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2617–25. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lowe ES, Kitchen BJ, Erdmann G, Stork LC, Bostrom BC, Hutchinson R, et al. Plasma pharmacokinetics and cerebrospinal fluid penetration of thioguanine in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a collaborative Pediatric Oncology Branch, NCI, and Children’s Cancer Group study. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2001;47:199–205. doi: 10.1007/s002800000229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McLeod SJ, Shum AJ, Lee RL, Takei F, Gold MR. The Rap GTPases regulate integrin-mediated adhesion, cell spreading, actin polymerization, and Pyk2 tyrosine phosphorylation in B lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12009–19. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313098200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baker EK, Johnstone RW, Zalcberg JR, El-Osta A. Epigenetic changes to the MDR1 locus in response to chemotherapeutic drugs. Oncogene. 2005;24:8061–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arakawa H. Netrin-1 and its receptors in tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:978–87. doi: 10.1038/nrc1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hankins GR, Sasaki T, Lieu AS, Saulle D, Karimi K, Li JZ, et al. Identification of the deleted in liver cancer 1 gene, DLC1, as a candidate meningioma tumor suppressor. Neurosurgery. 2008;63:771–80. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000325488.72518.9E. discussion 80–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu CX, Musco S, Lisitsina NM, Yaklichkin SY, Lisitsyn NA. Genomic organization of a new candidate tumor suppressor gene, LRP1B. Genomics. 2000;69:271–4. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rizzari C, Zucchetti M, Conter V, Diomede L, Bruno A, Gavazzi L, et al. L-asparagine depletion and L-asparaginase activity in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia receiving i.m. or i.v. Erwinia C. or E. coli L-asparaginase as first exposure. Ann Oncol. 2000;11:189–93. doi: 10.1023/a:1008368916800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsurusawa M, Chin M, Iwai A, Nomura K, Maeba H, Taga T, et al. L-Asparagine depletion levels and L-asparaginase activity in plasma of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia under asparaginase treatment. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2004;53:204–8. doi: 10.1007/s00280-003-0734-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pui CH, Robison LL, Look AT. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet. 2008;371:1030–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]