Abstract

The goal of this study is to examine a novel hypothesis that the progression of diabetes is partially due to the weakened survival of CD25high T cells, and prolonging survival of CD25high T cells inhibits the development of diabetes. Since CD28 co-stimulation is essential for the survival of CD4+CD25high T cells, we determined whether CD28-upregulated translationally controlled tumor protein (TCTP) prolongs the survival of CD4+CD25high regulatory T cells (Tregs) by a transgenic approach. The TCTP transgene prevents Tregs from undergoing apoptosis induced by Interleukin-2 withdrawal-, dexamethasone-, cyclophosphamide-, and anti-Fas treatment in vitro. In addition, transgenic Tregs express higher levels of FOXP3 than wild-type counterparts and maintain suppressive activity, suggesting that TCTP promotes Tregs escape from thymic negative selection, and that prolonged survival does not attenuate Treg suppression. Moreover, TCTP transgenic Tregs inhibit the development of autoimmune diabetes due to increased survival of suppressive Tregs and decreased expression of pancreatic TNF-α. Promoting the survival of CD25high T cells leads to prolonged survival of Tregs but not activated CD25+ non-Treg T cells. Thus, we propose a new model of “two phase survival” for Tregs. Our results suggest that modulation of Treg survival can be developed as a new therapy for autoimmune diseases.

Keywords: regulatory T cells, anti-apoptosis, TCTP, autoimmune diseases, diabetes

Decreased Treg numbers are associated with various autoimmune diseases, such as autoimmune diabetes (1). However, the mechanism underlying Treg reduction remains poorly defined. The deficiency in the CD28 co-stimulation results in an 80% decrease in the number of Tregs (2), suggesting that the generation and survival of Tregs is CD28 co-stimulation-dependent (3). Our recent report shows that expression of Bax, a pro-apoptotic protein in the Bcl-2 family, is higher in Tregs than in CD4+CD25- T cells, and that Tregs undergo apoptosis via a Bax-dependent pathway (4), suggesting that CD25high Tregs have higher susceptibility to apoptosis than CD25+ non-Treg T cells. Recently, we identified a novel Bcl-xL-interacting, anti-apoptotic protein, translationally controlled tumor protein (TCTP) (5), which inhibits Bax. Upregulated by T cell antigen receptor (TCR) ligation and CD28 co-stimulation(5), TCTP inhibits T cell apoptosis induced by IL-2 withdrawal. These results suggest that TCTP is a survival protein promoted by CD28 co-stimulation and IL-2 pathways.

For improving Treg reduction in autoimmune diseases and developing Treg-based immune therapeutics (6), a substantial quantity of well-survived suppressive Tregs would be needed. Therefore, three important questions remained to be answered: first, whether promotion of CD25high T cell survival leads to enhanced Treg survival or increased CD25+ non-Treg T cell survival; second, whether CD28 costimulation- and IL-2-signaled survival proteins play any critical roles in Treg apoptosis pathways; third, whether creation of Tregs that have prolonged survival inhibits diabetes. We established a CD25high T cell-specific TCTP transgenic mouse model (TCTP Tg) and answered these questions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Electrophoretic gel mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Promoter sequence analyses were performed using the TRANSFAC (http://www.cbil.upenn.edu/cgi-bin/tess/tess?RQ=SEA-FR-QueryS). EMSA was performed by using a Gelshift (activated T cell) kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA). The bold fonts in IL-2 CD28RE and TCTP CD28RE sequences were the previously reported core of CD28RE (7), and the underlined fonts were in the TCTP CD28RE mutant sequences (Fig. 1D).

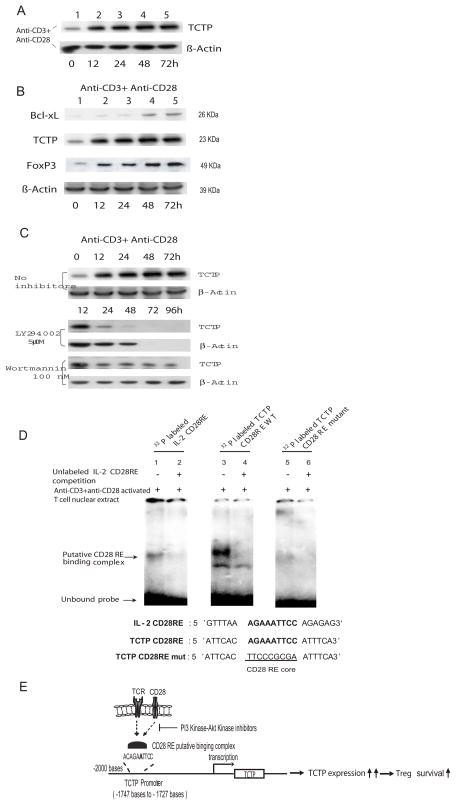

Fig. 1.

Upregulation of TCTP by TCR ligation and CD28 costimulation. A) Upregulation of TCTP expression in T cells activated by anti-CD3 antibody and anti-CD28 antibody in the time course of 0 hour (h), 12 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h. B) Co-upregulation of TCTP expression with anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-xL and Tregs transcription factor FOXP3 expression in T cells activated by anti-CD3 antibody and anti-CD28 antibody in the time course of 0 h, 12 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h. C) Inhibition of TCTP upregulation in T cells by PI3 kinase inhibitor LY294002 and Akt kinase inhibitor Wortmannin starting at 12 hours after T cell activation. Of note, β-actin expression was absent in the time point of 72 hours and 96 hours, which was due to massive cell death. D) Identification of a CD28 responsive element (CD28RE) in TCTP promoter by electrophoretic gel mobility shift assay (EMSA) (upper panel). In the lower panel, the sequences of CD28REs in mouse IL-2 promoter and in mouse TCTP promoter, and mutant TCTP CD28RE were aligned. E) A working hypothesis of TCTP upregulation in T cells activated by TCR ligation and CD28 costimulation presumably by a CD28RE-facilitated transcription mechanism.

Construction of CD25+ T cell-targeting TCTP transgenic mice

The construction of the CD25+ T cell transgenic vector pCD25-TCTP-Tg was described previously (4). Enforced expression of TCTP in these transgenic mice was confirmed by Western blot with anti-FLAG antibodies (Sigma). All mice used in the experiments were age- and sex-matched. All animal experiments were approved by Temple University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees.

Flow cytometric analysis

Lymphocytes were analyzed on FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) after staining with FITC-, PE-, and PE-Cy7-conjugated monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against: CD4, CD8a, GITR, CD3ε, and CD25 (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). PE-, PE-Cy7- and FITC-conjugated IgG were used as isotype controls (8). Intracellular staining of Foxp3 was performed using a Treg staining kit (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) with anti-FOXP3 antibody (clone FJK-16s).

T Cell Purification

Tregs were purified from spleens and lymph nodes (LN) by mouse Tregs isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) (9).

Suppressor Function Assay

Purified CD4+CD25- T cells were CFSE-labeled using the Cell Trace™ CFSE Kit (Invitrogen). CFSE+CD4+CD25- T cells (1.5 × 105) were cultured with 105 autologous T cell-depletedsplenic antigen-presenting cells (DynabeadsR Mouse Pan T -Thy1, 2, Invitrogen) in the presence of soluble anti-CD3ε (1 μg/ml). Various numbers (5 × 104, 2.5 × 104, 1.25 × 104 and 0.625 × 104) of Tregs were added to the cultures. Three days later, the cells were analyzed by FACS(9).

Western Blot

The following antibodies were purchased from companies: anti-TCTP antibodies from BD PharMingen; anti-FLAG tag antibodies from Sigma; anti-β-actin and Bcl-xL antibodies from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); anti-mouse/rat FOXP3 antibody from eBioscience; and anti-mouse TNF-α antibodies from the R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). PI-3 kinase inhibitor LY294002 and Akt kinase inhibitor Wortmannin were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, Michigan) and Millipore-Upstate (Billerica, MA), respectively.

T Cell Apoptosis Assay and IL-2 Withdraw Assay

Splenocytes were cultured in complete RPMI-1640 with 10% fetal calf serum (10) alone, 10 nM dexamethesone, anti-Fas Ab 100 ng/ml (clone Jo2) (BD PharMingen) or 1 mM cyclophosphamide (Sigma), respectively. For IL-2 deprivation, cells (1 × 106) were incubated with indicated concentrations of IL-2. After 24 hours, the cell were collected and stained by PE-conjugated CD25 and PE-Cy7-conjugated CD4. The apoptosis rates were measured by flow cytometry using Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit II (BD Pharmingen).

RNA Analysis

RNA preparation and RT-PCR analysis were performed as reported (10).

STZ-induced Autoimmune Diabetes

Tg and wild-type (WT) male mice (age 4 wk) received i.p. injections of 40 mg/kg STZ (Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in sodium citrate buffer (vehicle control) for 5 consecutive days. Non-fasting blood was obtained from the tail via a capillary tube and used for glucose level determination using ONETOUCH Ultra test Strips (LifeScan, Inc., Milpitas, CA). Mice were diagnosed as diabetic if non-fasting glucose levels were ≥250 mg/dl(11).

Histology

Pancreases were frozen in liquid nitrogen. Serial cryostatic sections (5 μm thick) were prepared for each pancreas. Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E)-staining and immunocytochemical experiments were used to study the presence of insulitis. Briefly, the acetone-fixed sections were subsequently stained with anti-FOXP3 mAb (BD PharMingen) overnight. After 3 washes with PBS-0.1% Tween 20, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Sigma), anti-rat/mouse Ig secondary antibodies conjugated with Texas Red (BD PharMingen) were applied (5). Photographs were taken by Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscopy (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

RESULTS

TCTP, an anti-apoptotic protein, is temporally co-upregulated with FOXP3 in T cells activated by TCR ligation and CD28 co-stimulation

We first asked whether TCR ligation with anti-CD3 antibody and CD28 co-stimulation with anti-CD28 antibody could enhance the upregulation of TCTP in T cells(5). TCR ligation plus CD28 co-stimulation upregulated TCTP expression (Fig. 1A). In addition, the scale of TCTP upregulation (Fig. 1B, blot 2) was higher than that of Bcl-xL (Fig. 1B, blot 1) in the same conditions, suggesting that the functional requirement for TCTP in supporting T cell survival and proliferation could be higher than that of Bcl-xL during T cell activation. Furthermore, the Treg-specific transcription factor FOXP3 was also co-upregulated with TCTP in mouse splenic T cells (Fig. 1B, blot 3) (3), suggesting that FOXP3 expression is upregulated in activated T cells, similar to that of CD25. Since CD28−/− deficient mice have only 20% of Tregs compared to wild-type controls (2), the results suggested that CD28 promoted survival signaling contributes significantly to Treg survival. Since it has been reported that CD28 co-stimulation signals through the PI3-Akt kinase pathway to promote T cell survival (12), we then asked whether TCTP upregulation by TCR ligation and CD28 co-stimulation is also mediated via PI3 kinase pathway. The results showed that the TCTP upregulation in activated T cells was significantly inhibited by PI3 kinase inhibitor LY294002 (Fig. 1C, blot 3) and Akt kinase inhibitor Wortmannin (Fig. 1C, blot 5). The results suggest that TCTP upregulation by CD28-co-stimulation requires the function of the PI3-Akt kinase pathway, which correlates with a previous report that PI3K signaling is critical for Treg survival (13). Taken together, these results suggest that TCTP may play an important role in a Treg survival promoted by CD28 co-stimulation signaling.

It was then determined whether TCTP upregulation by TCR ligation and CD28 co-stimulation was mediated by a promoter-dependent transcriptional mechanism. We reported that TCTP upregulation in activated T cells is temporally associated with upregulation of interleukin-2 (IL-2) secretion from activated T cells (5), suggesting that regulation of TCTP expression may be mediated by a signaling pathway similar to that regulating IL-2 expression. We thus examined the possibility of whether there is a cis-acting element in the TCTP promoter that may respond to CD28 co-stimulation. Our analyses of the TCTP promoter by searching the TRANSFAC database showed that a unique CD28 responsive element (CD28RE, a NF-κB like cis-acting element) (7) was located in the base pair (bp) -1747 of mouse TCTP promoter upstream of the transcription starting site. CD28 co-stimulation specifically targets the binding of CD28RE binding complex to CD28RE in IL-2 promoter, leading to a complete activation of the IL-2 promoter (12). The results of EMSA showed that a double-strand fragment of TCTP CD28 RE, similar to IL-2 CD28RE control (Fig. 1D, lane 1), could retain a band after binding to the proteins in the nuclear lysates of activated T cells (Fig. 1D, lane 3), which was abolished when a TCTP CD28RE core mutant fragment (Fig. 1D, the lower panel) was used in EMSA (Fig. 1D, lane 5). These results suggest that formation of TCTP CD28 RE-protein complex was the CD28RE core sequence-dependent. In addition, the TCTP CD28RE-protein complex (Fig. 1D, lane 3) co-migrated with the IL-2 promoter CD28 RE-protein complex (Fig. 1D, lane 1), suggesting that a similar protein complex may be formed. Furthermore, both IL-2 CD28RE-protein complex (Fig. 1D, lane 2) and TCTP CD28RE-protein complex were competed off (Fig. 1D, lane 4), respectively, in the presence of an excess amount of unlabelled IL-2 CD28RE fragment, suggesting that TCTP CD28 RE was a bona fide CD28RE with a core sequence identical to that of IL-2 CD28RE (Fig. 1D, the lower panel). Taken together, these results of upregulation of TCTP by CD28 co-stimulation and identification of CD28RE in TCTP promoter suggest that TCTP is a survival protein in CD28 survival pathway. Of note, our extensive search did not find the CD28RE sequences in the promoter regions of other related survival proteins including Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, Mcl-1 and A1 (5). Tregs have higher susceptibility to apoptosis (6), implying that expression of survival genes may be restricted to lower levels than those in CD4+CD25- T cells. Based on these results, we hypothesized that CD28 co-stimulation may promote Treg survival by upregulation of TCTP (Fig. 1E).

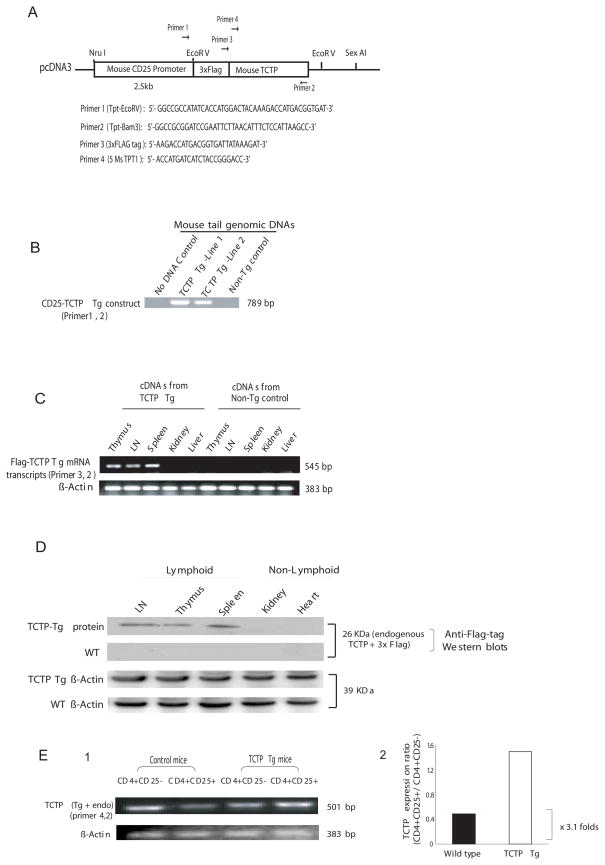

TCTP transgene promotes the survival and positive selection of CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ thymocytes

Two positive transgenic mouse strains were identified by mouse tail genomic DNA PCR using an mRNA-sense primer specific for the FLAG expression tag and an anti-sense primer specific for the TCTP sequence (Fig. 2A, B, lines 1 and 2). The RT-PCR analysis on cDNAs prepared from CD25-TCTP transgenic tissues and control mouse tissues using a sense primer specific for FLAG expression tag and an antisense TCTP primer showed that the TCTP transgenic transcripts were specifically expressed in lymphoid tissues including thymus, lymph nodes and spleen, but not in non-lymphoid tissues, such as liver and kidney nor in the lymphoid tissues from non-transgenic control littermates (Fig. 2C). The control PCR with RNA preparations without reverse transcription of lymphoid tissues and non-lymphoid tissues from CD25-TCTP transgenic mice did not yield specific amplification (not shown). These results suggest that (i) TCTP transgenic DNA amplifications in lymphoid tissues did not result from genomic DNA contamination, and (ii) TCTP transgenic mRNA transcripts were expressed in CD25 promoter-specific manner. In addition, the Western blot using anti-3xFLAG tag antibodies confirmed that TCTP transgenic protein was expressed in lymphoid tissues, such as thymus, lymph nodes and spleen, of CD25-TCTP transgenic mice but not in non-lymphoid tissues like liver and kidney (Fig. 2D, blot 1), nor in the lymphoid tissues and non-lymphoid tissues from wild-type control mice (Fig. 2D, blot 2). In contrast, β-actin as loading control was detected in every tissue examined (Fig. 2D, blots 3 and 4), suggesting that the absence of CD25-TCTP transcripts or protein in non-lymphoid tissues was due to the specific down-regulation of CD25 promoter. Furthermore, the semi-quantitative RT-PCR results presented in Fig. 2E showed that TCTP transcript expression in transgenic CD4+CD25+ T cells was increased at least by 3.1 fold in comparison to that in wild-type CD4+CD25+ T cells. The results from line 1 (Fig. 2C, D and E) were verified in the transgenic mice line 2. Collectively, these results showed that CD25-TCTP transgenic protein was expressed in the transgenic mice.

Fig. 2.

Generation of TCTP transgenic mouse model. A) TCTP transgenic construct. A 3X FLAG expression tag-fused TCTP cDNA was placed under the direction of mouse CD25 promoter. The locations of primers used for PCR detection of transgenic TCTP DNA, and RT-PCR detection of transgenic TCTP transcript and endogenous TCTP transcript are represented by arrows. In the lower panel, the primer sequences were presented. B) Detection of TCTP transgenic mice by PCR using mouse tail genomic DNAs as templates. No DNA template control and non-transgenic mouse (wild-type) tail DNA control were included. C) Detection of transgenic TCTP transcripts by RT-PCR. Equal amounts of RNAs prepared from non-lymphoid tissues (kidney and liver) from TCTP transgenic mice and counterpart tissues from non-transgenic wild-type control mice were used in the experiment. D) Detection of transgenic TCTP protein expression by Western blots with anti-3X FLAG tag antibody. Of note, transgenic TCTP protein was not detected in proteins prepared from tissues of non-lymphoid tissues in TCTP transgenic mice, which was not due to protein loading since equivalent amounts of β-actin expression was found in both non-lymphoid tissues and lymphoid tissues. E) Detection of TCTP transcripts (both transgenic and endogenous) by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. In the right panel, the ratios of TCTP expression density in CD4+CD25+ Treg cells and that of CD4+CD25- T cells are presented.

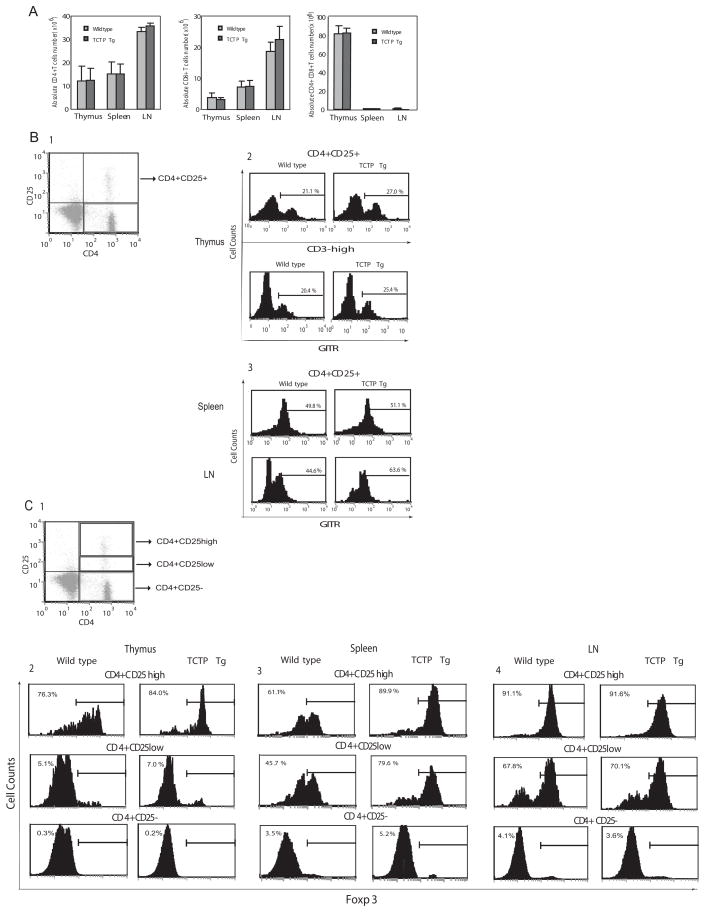

We examined whether the development of major subsets of thymocytes was affected by TCTP transgene. The FACS analysis showed, in Fig. 3A, that the absolute cell numbers of major thymocyte subsets including CD4+ single positive, CD8+ single positive, CD4+CD8+ double positive, and CD4-CD8- double negative in TCTP transgenic mice were not statistically different from that of wild-type littermate controls (p>0.05). In addition, the percentages of major T cell subsets including CD4+, CD8+ and CD4+CD8+ in peripheral splenocytes and lymphocytes in lymph nodes (LN) in TCTP transgenic mice were not significantly changed in comparison to that in wild-type (WT) control mice (p>0.05). These results suggest that the homeostasis of major T cell compartments is independent from a prolonged survival of Tregs. As shown in Fig. 3B-2, TCTP overexpression resulted in an elevated percentage (27.0%) of CD4+CD25+CD3high thymocytes in the CD4+ single positive fraction compared with 21.1% in the subset in control mice. Since GITR is another Tregs marker (6), we also examined the GITR+ fraction of CD4+CD25+ thymocytes and peripheral CD4+CD25+ T cells. The results showed increased percentage of CD4+CD25+GITR+ thymocytes from 20.4% in wild-type controls to 25.4% in TCTP transgenic mice. In correlation with this finding, we also found that CD4+CD25+GITR+ Tregs fraction in lymph nodes was significantly increased from 44.6% in wild-type controls to 63.6% in TCTP transgenic mice (Fig. 3B-3, lower panel). In addition, since FOXP3 expression is a Treg specific transcription factor (6), we found that the percentage of CD4+CD25highFOXP3+ thymocytes was increased from 76.3% in wild-type controls to 84.0% in TCTP transgenic mice (Fig. 3C-2, top left panel). The percentage of CD4+CD25highFOXP3+ splenic Tregs was significantly increased from 61.1% in wild-type controls to 89.9% in TCTP transgenic mice (Fig. 3C-3, top middle panel). In addition to increased percentage of splenic FOXP3+ cells, the expression levels of FOXP3 in splenic CD4+CD25high T cells as judged by the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) were higher in TCTP transgenic mice than that in wild-type controls (not shown). Of note, the percentage of CD4+CD25highFOXP3+ Tregs in lymph nodes (91.1%) of TCTP transgenic mice was not significantly higher than that (91.6%) in wild-type control mice (Fig. 3C-4, top right panel). Moreover, we found that the increased percentages of FOXP3+ were mostly residing in the CD4+CD25high fraction of thymocytes and splenocytes in TCTP transgenic mice in comparison to that in wild-type controls, except that CD4+CD25lowFOXP3+ Tregs were also increased in splenocytes (Fig. 3C-3, middle panel). The results further demonstrated that TCTP overexpression resulted in increased FOXP3+ Tregs. Of note, these results were verified in mice from both TCTP transgenic lines (not shown), suggesting that phenotyping changes resulted from TCTP transgenic protein function. These results suggest that TCTP transgene promotes the survival and positive selection of CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ thymocytes (14), and that CD28 co-stimulation promotes the generation of CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ thymocytes at least partially via the function of anti-apoptotic protein TCTP.

Fig. 3.

Phenotypes of TCTP transgenic mice. A) FACS analysis of CD4+ single positive and CD8+ single positive, and CD4+CD8+ double positive thymocytes, splenic T cells and lymph node (LN) T cell populations in TCTP transgenic mice and wild-type control mice. B1) Gated CD4+CD25+ cells for further analysis. B2) FACS analysis of CD4+CD25+CD3high and CD4+CD25+GITR+ cell populations in TCTP transgenic thymus and wild-type control thymus. B3) FACS analysis of CD4+CD25+GITR+ cell populations in TCTP transgenic spleen and lymph nodes (LN) and wild-type control spleen and lymph nodes. C1) Gated CD4+CD25+ cells for further analysis. C2) FACS analysis of FOXP3 expression in CD4+CD25−, CD4+CD25low and CD4+CD25high cell populations in TCTP transgenic thymus and wild-type control thymus. Similarly, the data of FACS analysis of FOXP3 expression in CD4+CD25−, CD4+CD25low and CD4+CD25high cell populations in TCTP transgenic spleen and lymph nodes and wild-type control spleen and lymph nodes are presented in C3 and C4, respectively.

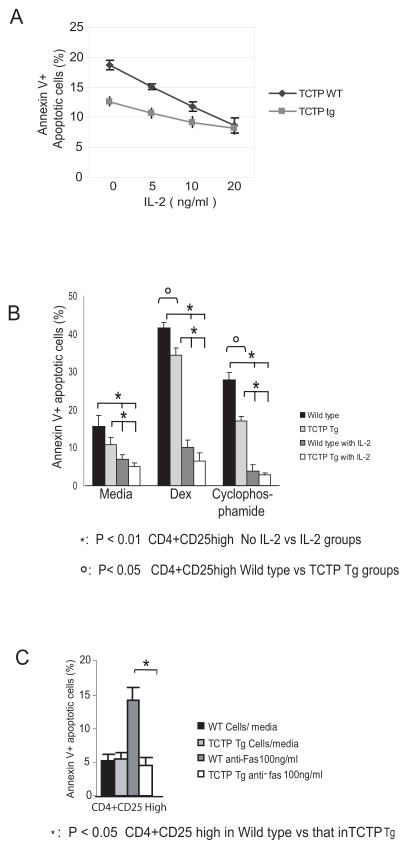

TCTP transgene inhibited apoptosis of CD4+CD25high T cells

Tregs are poor IL-2 producers (15). Since sharing the CD28RE transcription mechanism with IL-2, TCTP may also be expressed in Tregs in low levels, which may be responsible for higher susceptibility of Tregs to apoptosis. The results presented in the left two lanes in Fig. 2E (CD4+CD25- T cells and CD4+CD25+ T cells from wild-type mice) supported this analysis. TCTP transgene promotes the survival and positive selection of CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ thymocytes. In addition, the percentage of CD4+CD25highFOXP3+ splenic Tregs was significantly increased from 61.1% in wild-type controls to 89.9% in TCTP transgenic mice. Moreover, the results, in Fig. 4A, showed that transgenic TCTP inhibited apoptosis of CD4+CD25high Tregs induced by IL-2 withdrawal (IL-2, 0 ng/ml) from 18.7% in wild-type controls to 12.7% in TCTP transgenic mice. When IL-2 supply was increased from 0 ng/ml to 20 ng/ml, the differences in apoptotic cell percentages between the TCTP Tregs and wild-type Tregs were decreased gradually, suggesting that at least in the IL-2 concentration range of 0 ng/ml to 10 ng/ml of IL-2 (Fig. 4A), TCTP transgene replaced IL-2-mediated Treg survival signal. Furthermore, the results showed that, in Fig. 4B, CD4+CD25+ Tregs were more susceptible to apoptosis induced by IL-2 withdrawal plus dexamethasone treatment, in which TCTP transgenic protein inhibited Treg apoptosis from 43.7% in wild-type mice to 36.4% in TCTP transgene (p<0.05). Similarly, transgenic TCTP reduced Treg apoptosis induced by cytotoxic drug cyclophosphamide from 27.6% in wild-type controls to 20.6% in TCTP transgenic Tregs (Fig. 4B) (p<0.05). The results suggest that TCTP transgene confers more resistance of Tregs to apoptosis induced by dexamethasone and cyclophosphamide. Finally, in Fig. 4C, the results show that TCTP transgene inhibited Treg apoptosis induced by anti-Fas antibody from 14.2% in WT control Tregs to 4.5% in TCTP Tg Tregs in the presence of IL-2 at 5ng/ml (p<0.05). It was reported that Tregs are highly susceptible to CD95 ligand-mediated apoptosis (6). Our results suggest that TCTP also inhibits death receptor Fas-initiated apoptosis.

Fig. 4.

TCTP transgenic Treg resistance to apoptosis. A) Resistance of TCTP transgenic Tregs to apoptosis. Splenocytes from wild-type control mice (black line) and TCTP transgenic mice (grey line) were incubated in the presence of 0 ng/ml, 1 ng/ml, 5 ng/ml and 20 ng/ml of IL-2 for 24 hours followed by FACS analysis of apoptotic CD4+CD25high Tregs with FITC-Annexin V. The experiments were repeated three times. B) FACS analysis of resistance of TCTP transgenic Tregs and wild-type control Tregs to apoptosis induced by Dexamethasone (Dex) and cyclophosphamide in the absence or presence of IL-2. C) FACS analysis of resistance of CD4+CD25high Tregs from wild-type control mice and TCTP transgenic mice to apoptosis induced by anti-Fas antibody in the presence of IL-2 (5 ng/ml).

CD4+CD25high regulatory T cells from TCTP Tg mice maintained their suppressive function

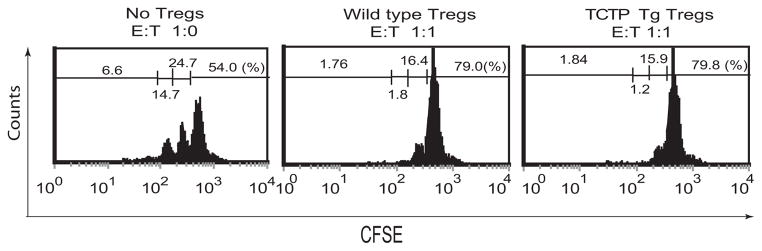

An important issue remained to be addressed: whether Treg suppressive function is coupled to their higher apoptotic status. In other words, whether Tregs that have a prolonged survival maintain their suppressive function. TCTP Treg transgenic mice provide a unique experimental system to examine this issue. In the previous section (Fig. 3C-2, top center panel), we demonstrated that CD4+CD25highFOXP3+ splenic Tregs in TCTP transgenic mice were increased (1.47 fold) from 61.1% in wild-type controls to 89.9%, suggesting the maintenance of suppressive function of TCTP transgenic Tregs. Thus, next question was whether survived Tregs in TCTP transgenic mice really retain their suppressive function in addition to FOXP3 expression. CFSE-labeled CD4+CD25- T cell proliferation was used as a read-out assay for examining Treg suppression. Purified CD4+CD25high T cells had 93.8% CD25+ phenotype (not shown), suggesting that the purification procedure was successful. After co-incubation of Tregs with CFSE-labeled CD4+CD25- T cells in a ratio of 1:1, the no-proliferation cell percentage with the highest fluorescence of CFSE was increased from 54% (Fig. 5, left panel) in no-Treg control group to 79.0% in wild-type Tregs control group (Fig. 5, middle panel), suggesting that CFSE-labeled CD4+CD25- T cell proliferation was suppressed by wild-type Tregs. Similarly, in the same conditions, Tregs from TCTP transgenic mice also made the no-proliferation cell percentage with the highest fluorescence of CFSE, and were increased from 54% in the non-Treg control group to 79.8% (Fig. 5, right panel), suggesting that TCTP Tregs are suppressive. Taken together, the results suggest that Tregs in TCTP transgenic mice with a prolonged survival retain their higher FOXP3 expression and suppressive function.

Fig. 5.

In vitro assay for Treg suppressive function. In vitro suppression of CD4+CD25- T cell proliferation (as judged by CFSE fluorescence dilution) by no Treg control (left panel), wild-type Tregs (middle panel) and TCTP transgenic Tregs (right panel). The fluorescence intensity of CFSE-labeled CD4+CD25− T cells was decreased to 50% in every cell division. The Treg suppressive function was measured by the percentage (%) of CFSE-labeled cell fractions in higher fluorescence intensities in the absence of Tregs (CD4+CD25− T cell proliferation control, left panel) and in the presence of Tregs from wild-type control mice (middle panel) and TCTP transgenic mice (right panel). “E” indicates the effector T cells, and “T” shows “Tregs”. The experiments were repeated three times.

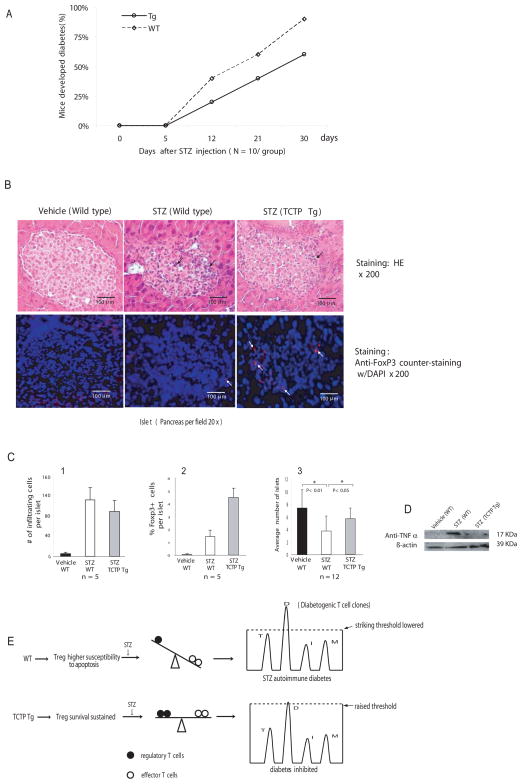

Transgenic TCTP delayed the onset of STZ-induced diabetes

To further examine Treg suppressive function from TCTP transgenic mice, a T cell-dependent model of autoimmune diabetes (16–17) induced by multiple low dose of STZ was adopted. Of note, Treg suppression depends not only on cell-cell contact but also on the function of suppressive cytokines TGF-β and IL-10 (6). A recent report showed that protection of animals from development of STZ-induced diabetes by anti-CD3 is TGF-β-dependent (17), suggesting a possibility that Tregs may suppress STZ-induced autoimmune diabetes. Thus, we asked whether Tregs that have a prolonged survival in TCTP transgenic mice could inhibit the development of STZ-induced diabetes more efficiently. As shown in Fig. 6A, the incidence of STZ-induced diabetes was decreased from 45% in wild-type control group to 22% in the TCTP transgenic mouse group at day 12 after the first dose of STZ injection, and was decreased from 63% in wild-type controls to 43% in TCTP transgenic mice at day 21. By histological examination of pancreas tissue with H&E staining (Fig. 6B, upper panel), we found that STZ injections caused less infiltration of inflammatory cells (85 cells/islet) in TCTP transgenic pancreas in comparison to that of wild-type controls (133 cells/islet) (Fig. 6C-1). In addition, the results (Fig. 6B, lower panel) show that (a) FOXP3 staining was co-localized with DAPI (a nuclear DNA fluorescence dye), which correlated with reported sub-cellular location of transcription factor FOXP3; (b) more FOXP3+ positive cells were seen in the β-islet areas from TCTP transgenic mice (4.5 cells/islet) than that in wild-type pancreas controls (1.5 cells/islet). Moreover, STZ decreased the average islet number per section from 7.5 in wild-type vehicle control to 3.8 in STZ-treated wild-type controls (p<0.01) (Fig. 6C-3), suggesting STZ-induced islet destruction. In contrast, TCTP transgenic mice protected pancreas islets from STZ-induced immune destruction, as judged by increasing islet numbers from 3.8 islets/section in STZ-treated wild-type controls to 6 islets/section in STZ-treated TCTP transgenic mice (Fig. 6C-3) (p<0.05). Finally, since proinflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) was found to be upregulated in STZ induced autoimmune diabetes(18), we further examined the issue whether Tregs in TCTP transgenic mice inhibit upregulation of TNF-α in the inflamed pancreas induced by STZ. STZ treatment significantly induced TNF-α upregulation in pancreas (Fig. 6D), which was inhibited in STZ-treated TCTP transgenic pancreas. Taken together, the results were summarized by proposing a new working model, as shown in Fig. 6E. STZ-treatment induces autoimmune diabetes, in which wild-type Tregs with higher susceptibility to apoptosis presumably could not suppress diabetogenic T cell clones. In contrast, TCTP transgene improves the survival of Tregs while maintaining their suppressive function, which presumably raises the striking threshold of diabetogenic T cell clones and inhibits development of diabetes more efficiently.

Fig. 6.

Inhibition of the development of STZ-induced autoimmune diabetes. A) Reduction of the percentages of TCTP transgenic mice that have developed diabetes induced by repeated low-dose STZ injections. The experiments were repeated three times, and the representative results are presented. B) Histological analysis of pancreatic islets and immunofluorescence of FOXP3+ cells in pancreatic islets. In the upper panel, after staining with H&E, the lymphocyte infiltrates in the pancreas are marked with arrows. In the lower panel, pancreatic slides were stained with fluorescence-labeled anti-FOXP3 antibody and counter-stained with nuclear dye DAPI. The cells stained by the red fluorescence (FOXP3 antibody) and overlapped with counter-stained DAPI fluorescence are marked as FOXP3+ cells. C) Summary of small lymphocyte infiltrates per islet (C1), FOXP3+ cells per islet (C2), and average numbers of islets in each pancreas section (C3). D) Western blot analysis of TNF-α expression stimulated by STZ in TCTP Tg pancreas and in wild-type pancreas. E) A working model in which Tregs with prolonged survival inhibit development of STZ-induced autoimmune diabetes. Wild-type Tregs with higher susceptibility to apoptosis presumably could not cope with the lowered striking threshold of STZ-induced autoimmune diabetogenic T cell clones. Tregs from TCTP transgenic mice with improved survival can improve the balance between Tregs versus effector T cells and inhibit the development of STZ-induced autoimmune diabetes, presumably via elevating the striking threshold for diabetogenic T cell clones. In the right panel, the letters “T”, “D”, “I” and “M” indicate the putative T cell clones mediating autoimmune diseases, such as thyroiditis, diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, and myositis, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Genetic analysis of type I diabetes showed that IL-2 (Idd3) is among the several gene loci that determine the susceptibility to the disease (19), suggesting that Treg survival affected by insufficient IL-2 supply may contribute to development of autoimmune diabetes. Our current study demonstrates for the first time the following findings: (a) CD25high Tregs have higher susceptibility to apoptosis than CD25+ non-Treg T cells, since promotion of CD25 promoter-survival protein TCTP Tg results in increased Treg survival more than CD25+ non-Treg T cell survival; (b) CD28 promotion of Treg survival is contributed via TCTP upregulation; (c) transgenic TCTP can replace IL-2 survival signal, and inhibit Treg apoptosis induced by IL-2 withdrawal, chemotherapy drugs dexamethasone and cyclophosphamide, and death receptor Fas ligation; (d) Tregs in TCTP transgenic mice maintain their high expression levels of FOXP3 and suppressive function. In contrast to the loss of Treg suppressive activity in the presence of anti-GITR and anti-OX40 agonist antibodies, it was found that increased Treg survival is not coupled with loss of Treg suppression; (e) promotion of Treg survival by TCTP Tg significantly inhibits the progression of STZ-induced autoimmune diabetes. Therefore, the results proved the principle that Treg specific apoptotic pathways can be targeted for therapeutic intervention of autoimmune diabetes; and Tregs having a prolonged survival are still suppressive, which make production of a large number of suppressive Tregs for Tregs-based therapy feasible.

Identification of CD28RE in TCTP promoter suggests that expression of TCTP upregulated by CD28 co-stimulation was transcription-mediated, suggesting that definition of TCTP role in regulating CD25high T cell survival by transgenic approach was justified. Previous studies showed that the CD25 promoter is capable of targeting the transgenic reporter gene in T cells with a CD25-specific expression pattern (20). Up to 96% of CD4+CD25high Tregs express FOXP3 (21), suggesting that CD25high is an essential marker for FOXP3+ Tregs (22–23). In addition, the transgenic TCTP promotes more survival of CD25highFOXP3+ Tregs than that of CD4+CD25+intermediate, proving the suitability of CD25 promoter. Of note, FOXP3 per se promotes Treg apoptosis (24), and FOXP3 expression in activated T cells leads to not necessarily acquisition of suppression function (25). In order to determine whether CD25high Tregs have higher susceptibility to apoptosis than CD25+ non-Treg T cells, we used CD25 promoter for this study, whereas FOXP3 promoter may not be suitable for this purpose.

In addition, the following evidence suggests that adoption of STZ-induced diabetes model in this study is appropriate: Firstly, multiple low dose of STZ-induced diabetes is a well-characterized T cell-mediated autoimmune diabetes (16–17, 26); secondly, the susceptibility genes of mice to STZ-induced diabetes are mapped to the same gene loci that are responsible for development of spontaneous diabetes in NOD mice (27), suggesting the similarity of autoimmune mechanism in contributing to the development of diabetes in both models; thirdly, the potential role of Tregs in suppression of STZ-induced diabetes has been reported (11).

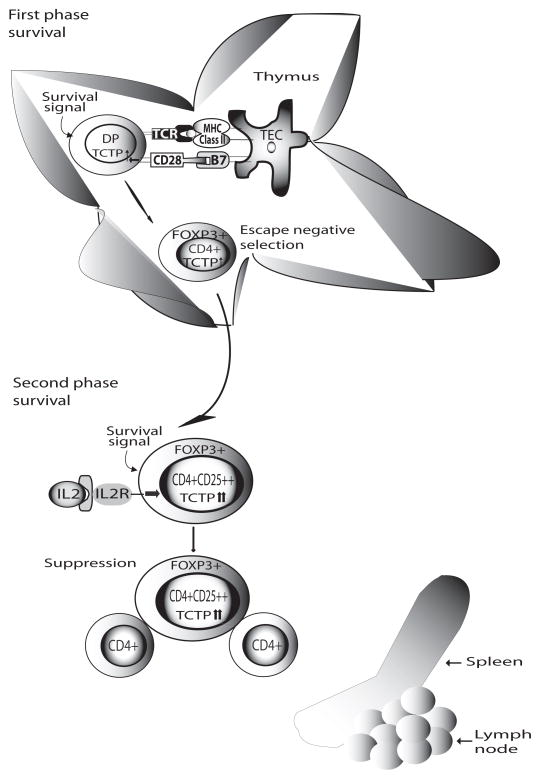

These results further suggest that TCTP inhibits death-receptor Fas-mediated apoptosis, presumably due to the fact that TCTP inhibits truncated Bid-mediated mitochondrion-dependent pathway triggered by Fas signaling (28). Since Tregs have higher susceptibility to apoptosis, especially to the stimuli including IL-2 withdrawal-induced apoptosis (29–30) and FasL-mediated apoptosis (31), our results suggest the importance of TCTP in inhibition of both Treg apoptosis pathways. This and other data show that CD28 co-stimulation plays a critical role for Treg survival via upregulation of survival molecules TCTP, Bcl-xL and Treg transcription factor FOXP3 (32). We therefore propose a new model of “two phase survival” for Tregs (Fig. 7): In the first phase, CD28-promoted survival signal plays a dominant role for FOXP3+Tregs to “escape” the negative selection of thymocytes; even TCRs on Tregs have high affinity for self-peptide/MHC complex expressed at thymic epithelial cells (33). Several reports from this and other labs support this part of the model. CD28 co-stimulation is essential for Tregs generation, since CD28−/− deficient mice have only 20% of Tregs in comparison to that in wild-type mice (2). CD28 co-stimulation significantly promotes T cell survival by upregulating numerous anti-apoptotic proteins, Bcl-xL(34), Bcl-xγ(10), and TCTP (5), suggesting that promotion of Treg generation by CD28 is fulfilled by enhancing upregulation of anti-apoptotic proteins and Treg escape from thymic negative selection. TCTP transgene increased CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ thymocytes, which further consolidates this model. Whether IL-2 signaled survival plays an essential role for thymic development of Tregs is a debatable issue (22, 35). In the second phase, IL-2/IL-2R signal plays a decisive role in Treg survival in the periphery. These and other results support the second phase model. Tregs are anergic and poor IL-2 producers (15). In addition, CD28 signaling is not functional in promoting IL-2 and TCTP transcription and Tregs survival. In contrast, Tregs are dependent on paracrine IL-2 for survival(22). TCTP transgene significantly contributes to IL-2-mediated Tregs survival pathway in peripheral. Taken together, the importance of TCTP in both phases of Treg survival revealed in this study further suggest the potential of the pathway to be targeted for therapy.

Fig. 7.

A working model of two phase Tregs survival. In the first phase, CD28-promoted survival signal plays a dominant role for FOXP3+Tregs to “escape” the negative selection of thymocytes even TCRs on Tregs have high affinity for self-peptide/MHC complex expressed at thymic epithelial cells. In the second phase, IL-2/IL-2R signal plays a decisive role in Treg survival in the periphery. The data suggest that TCTP plays an important role in both phases of Treg survival.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs. D. Huston, S.H. Han, and T.H. Tan at Baylor College of Medicine, P. Reichenbach and M. Nabholz at Swiss Cancer Center, B. Ashby and N. Dun at Temple University for assistance. This work was partially supported by NIH grant AI054514.

References

- 1.Glisic-Milosavljevic S, Waukau J, Jailwala P, et al. At-risk and recent-onset type 1 diabetic subjects have increased apoptosis in the CD4+CD25+ T-cell fraction. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salomon B, Lenschow DJ, Rhee L, et al. B7/CD28 costimulation is essential for the homeostasis of the CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells that control autoimmune diabetes. Immunity. 2000;12:431–440. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tai X, Cowan M, Feigenbaum L, et al. CD28 costimulation of developing thymocytes induces FOXP3 expression and regulatory T cell differentiation independently of interleukin 2. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:152–162. doi: 10.1038/ni1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yan Y, Chen Y, Yang F, et al. HLA-A2.1-restricted T cells react to SEREX-defined tumor antigen CML66L and are suppressed by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2007;20:75–89. doi: 10.1177/039463200702000109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang Y, Yang F, Xiong Z, et al. An N-terminal region of translationally controlled tumor protein is required for its anti-apoptotic activity. Oncogene. 2005;24:4778–4788. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang XF. Factors regulating apoptosis and homeostasis of CD4+CD25highFOXP3+ regulatory T cells are new therapeutic targets. Front Biosci. 2008;13:1472–1499. doi: 10.2741/2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lai JH, Horvath G, Subleski J, et al. RelA is a potent transcriptional activator of the CD28 response element within the interleukin 2 promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4260–4271. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiong Z, Song J, Yan Y, et al. Higher expression of Bax in regulatory T cells increases vascular inflammation. Front Biosci. 2008;13:7143–7155. doi: 10.2741/3217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thornton AM, Donovan EE, Piccirillo CA, et al. Cutting edge: IL-2 is critically required for the in vitro activation of CD4+CD25+ T cell suppressor function. J Immunol. 2004;172:6519–6523. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.6519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang XF, Weber GF, Cantor H. A novel Bcl-x isoform connected to the T cell receptor regulates apoptosis in T cells. Immunity. 1997;7:629–639. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80384-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anastasi E, Campese AF, Bellavia D, et al. Expression of activated Notch3 in transgenic mice enhances generation of T regulatory cells and protects against experimental autoimmune diabetes. J Immunol. 2003;171:4504–4511. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.9.4504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kane LP, Lin J, Weiss A. It’s all Rel-ative: NF-kappaB and CD28 costimulation of T-cell activation. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:413–420. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02264-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walsh PT, Buckler JL, Zhang J, et al. PTEN inhibits IL-2 receptor-mediated expansion of CD4+ CD25+ Tregs. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2521–2531. doi: 10.1172/JCI28057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Picca CC, Larkin J, 3rd, Boesteanu A, et al. Role of TCR specificity in CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T-cell selection. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:74–85. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de la Rosa M, Rutz S, Dorninger H, et al. Interleukin-2 is essential for CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell function. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:2480–2488. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herold KC, Vezys V, Koons A, et al. CD28/B7 costimulation regulates autoimmune diabetes induced with multiple low doses of streptozotocin. J Immunol. 1997;158:984–991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishikawa H, Ochi H, Chen ML, et al. Inhibition of autoimmune diabetes by oral administration of anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody. Diabetes. 2007;56:2103–2109. doi: 10.2337/db06-1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holstad M, Sandler S. A transcriptional inhibitor of TNF-alpha prevents diabetes induced by multiple low-dose streptozotocin injections in mice. J Autoimmun. 2001;16:441–447. doi: 10.1006/jaut.2001.0506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maier LM, Wicker LS. Genetic susceptibility to type 1 diabetes. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:601–608. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soldaini E, Pla M, Beermann F, et al. Mouse interleukin-2 receptor alpha gene expression. Delimitation of cis-acting regulatory elements in transgenic mice and by mapping of DNase-I hypersensitive sites. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:10733–10742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.18.10733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roncador G, Brown PJ, Maestre L, et al. Analysis of FOXP3 protein expression in human CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells at the single-cell level. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1681–1691. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malek TR, Bayer AL. Tolerance, not immunity, crucially depends on IL-2. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:665–674. doi: 10.1038/nri1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scheffold A, Huhn J, Hofer T. Regulation of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell activity: it takes (IL-)two to tango. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1336–1341. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kasprowicz DJ, Droin N, Soper DM, et al. Dynamic regulation of FOXP3 expression controls the balance between CD4(+) T cell activation and cell death. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:3424–3432. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J, Ioan-Facsinay A, van der Voort EI, et al. Transient expression of FOXP3 in human activated nonregulatory CD4+ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:129–138. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herold KC, Vezys V, Sun Q, et al. Regulation of cytokine production during development of autoimmune diabetes induced with multiple low doses of streptozotocin. J Immunol. 1996;156:3521–3527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Babaya N, Ikegami H, Fujisawa T, et al. Susceptibility to streptozotocin-induced diabetes is mapped to mouse chromosome 11. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;328:158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valentijn AJ, Gilmore AP. Translocation of full-length Bid to mitochondria during anoikis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:32848–32857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313375200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taams LS, Smith J, Rustin MH, et al. Human anergic/suppressive CD4(+)CD25(+) T cells: a highly differentiated and apoptosis-prone population. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1122–1131. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200104)31:4<1122::aid-immu1122>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen X, Murakami T, Oppenheim JJ, et al. Differential response of murine CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25- T cells to dexamethasone-induced cell death. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:859–869. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fritzsching B, Oberle N, Eberhardt N, et al. In contrast to effector T cells, CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells are highly susceptible to CD95 ligand- but not to TCR-mediated cell death. J Immunol. 2005;175:32–36. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gavin MA, Rasmussen JP, Fontenot JD, et al. Foxp3-dependent programme of regulatory T-cell differentiation. Nature. 2007;445:771–775. doi: 10.1038/nature05543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bensinger SJ, Bandeira A, Jordan MS, et al. Major histocompatibility complex class II-positive cortical epithelium mediates the selection of CD4(+)25(+) immunoregulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2001;194:427–438. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boise LH, Minn AJ, Noel PJ, et al. CD28 costimulation can promote T cell survival by enhancing the expression of Bcl-XL. Immunity. 1995;3:87–98. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90161-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.D’Cruz LM, Klein L. Development and function of agonist-induced CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in the absence of interleukin 2 signaling. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1152–1159. doi: 10.1038/ni1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]