Abstract

Background

Atrial fibrillation (AF) promotes atrial remodeling and can develop secondary to heart failure (HF) or mitral valve disease. Cardiac endothelin-1 (ET-1) expression responds to wall stress, and can promote myocyte hypertrophy and interstitial fibrosis. We tested the hypothesis that atrial ET-1 is elevated in AF and is associated with AF persistence.

Methods and Results

Left atrial appendage (LAA) tissue was studied from coronary artery bypass graft, valve repair, and/or Maze procedure patients in sinus rhythm with no history of AF (SR, n=21), with history of AF but in SR at surgery (AF/SR, n=23), and in AF at surgery (AF/AF, n=32). The correlation of LA size with atrial protein and mRNA expression of ET-1 and ET-1 receptors (ETAR and ETBR) was evaluated.

LAA ET-1 content was higher in AF/AF than in SR, but receptor levels were similar. Immunostaining revealed that ET-1 and its receptors were present both in atrial myocytes and in fibroblasts. ET-1 content was positively correlated with LA size, HF, AF persistence, and severity of mitral regurgitation (MR). Multivariate analysis confirmed associations of ET-1 with AF, hypertension (HTN) and LA size. LA size was associated with ET-1 and MR severity. ET-1 mRNA levels were correlated with genes involved in cardiac dilatation, hypertrophy and fibrosis.

Conclusion

Elevated atrial ET-1 content is associated with increased LA size, AF rhythm, HTN and HF. ET-1 is associated with atrial dilatation, fibrosis and hypertrophy, and likely contributes to AF persistence. Interventions that reduce atrial ET-1 expression and/or block its receptors may slow AF progression.

Keywords: Endothelin, Atrial fibrillation, Heart failure, Mitral valve, Atrium

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) increases risk of stroke, morbidity and mortality. AF is present in 50% of patients undergoing mitral valve surgery and in 5–50% of patients with hypertension (HTN) and heart failure (HF)1, 2. Atrial structural remodeling, encompassing myocyte hypertrophy, chamber dilatation and interstitial fibrosis, contributes to the development and progression of AF3. Increased LA size reflects chronically increased atrial volume or pressure, and LA dilatation is associated with a poor clinical prognosis4.

Stressors that promote atrial structural remodeling include HTN5, mitral valve regurgitation (MR)6, HF7, AF8, and myocardial ischemia. Common to these pathologies is endothelin-1 (ET-1), an autocrine and paracrine mediator with mitogenic, inotropic and arrhythmogenic activity in cardiac muscle9. ET-1 expression and release are promoted by a variety of stimuli, including hypoxia10, ischemia, increased wall shear stress, stretch, and pressure overload, both in vitro11 and in vivo12. Elevated ET-1 levels may promote atrial dilatation, hypertrophy and fibrosis. Increased atrial wall stress is associatedwith increased atrial collagen deposition13, and ET-1 promotes fibroblast proliferation and extracellular matrix production8. Changes in atrial geometry, conduction heterogeneity, and size may predispose the atria to persistent arrhythmia. Plasma ET-1 levels are reported to be elevated in AF patients with underlying heart disease14 and in patients with HF and valvular heart disease15. In HF patients, plasma ET-1 level was a strong and independent predictor of AF15.

Although elevated plasma ET-1 has been associated with increased risk of AF, local production and regulation of ET-1 in the atria has not yet been studied. Here we tested the hypothesis that atrial ET-1 is increased in AF and is associated with LA enlargement, atrial fibrosis and AF persistence in patients with underlying cardiovascular disease.

Methods

Detailed descriptions of all methods are presented in the Online Methods and Data Supplement

Patient Selection

Left atrial appendage (LAA) specimens were obtained from patients referred to the Cleveland Clinic for cardiac surgical procedures in which the LAA was excised. Most patients had underlying structural heart disease. Clinical, laboratory and demographic data were obtained by query of the Cardiovascular Information Registry, a comprehensive surgical database. All patients provided informed consent; the protocol was approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Patient samples were categorized into three groups based on arrhythmia history. Control patients were in sinus rhythm (SR), with no history of AF or atrial flutter, but had other cardiac conditions requiring surgery (e.g., coronary artery disease (CAD), mitral valve disease (MVD), HF). AF patients included both those presenting to surgery in AF (AF/AF) and in SR (AF/SR), as documented on the last electrocardiogram prior to surgery. Patients included in the SR, AF/AF and AF/SR groups were matched for age, gender, history of HF, HTN, and MR.

Echocardiographic Analysis of Left Atrial Dimensions

Digitally archived echocardiographic recordings were sequentially reviewed and left atrial dimensions were assessed in two and four chamber views by a single, experienced cardiologist (A.Z.). Left atrial diameters and volumes were indexed to body surface area (iLAD, iLAV)16.

Enzyme linked immunoassay for atrial ET-1

After transport from the operating room to the laboratory, separate sections of each LAA specimen were fixed in paraformaldehyde, or stored at −80°C for confocal and biochemical studies. ET-1 content of atrial homogenates was evaluated using an enzyme-linked immunoassay (Biomedica BI-20052).

Western analysis

Western blots were used to evaluate ETA and ETB receptor protein expression in LAA homogenates. Proteins were extracted, quantified and probed with rabbit anti-ETAR or ETBR (1:200, Alomone Labs) as previously described8.

Microarray analysis

Total RNA was isolated from each specimen (Trizol) and mRNA levels were assayed using the Illumina HT12 microarray platform.

Immunostaining and confocal microscopy

Immunostaining and confocal microscopy was used to evaluate the distribution of ET-1 and its receptors (ETAR and ETBR) in LAA tissues as previously described8.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard error, unless otherwise specified. Univariate and multivariate linear regression analyses were performed to evaluate the association of clinical and demographic variables with atrial ET-1 levels and LA size. Normally distributed variables are presented using bar plots and analyzed using ANOVA. Non-normally distributed variables are presented using box plots and analyzed using Mann-Whitney or Kruskal-Wallis tests. Spearman’s correlation was used to measure relation of ET-1 mRNA to variables that were not normally distributed. Univariate analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 4; multivariate analyses were performed using JMP 7. Because atrial ET-1 levels were not normally distributed, a square root transformation of ET-1 levels was used in the multivariate linear regression model. The square root transformation of atrial ET-1 effectively normalized the dataset. Values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Atrial endothelin-1 and endothelin-1 receptor studies

Patient Characteristics

LAA tissues from 76 patients were selected for biochemical and immunohistochemical analysis of atrial ET-1 and ET-1 receptor expression. Table 1 shows the three groups stratified based on atrial rhythm and prospectively matched by age, gender, and by cardiovascular comorbidities including HF, HTN and valvular disease: control patients SR (N=21), patients with a history of AF but in SR at time of surgery (AF/SR, N=23), and patients with a history of AF, presenting in AF at time of surgery (AF/AF, N=32). Surgical patients have complex cardiovascular problems, and many underwent treatment for more than one disorder (eg., mitral valve repair, coronary artery bypass graft and Maze procedure, Table 1). These patients had significant cardiovascular disease; HTN, HF, CAD, and valvular diseases were present in 50%, 31%, 36%, and 78% of patients, respectively. LA dimensions were similar between rhythm groups; most patients had dilated left atria (median (IQR): 4.76 (4.11–5.13) cm).

Table 1.

Patients characteristics (Tissue biochemistry, histology studies)

| SR (n=21) | AFSR (n=23) | AFAF (n=32) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Characteristics | ||||

| Age, years | 64 ± 2.9 | 64.1 ± 2.2 | 62.7 ± 1.9 | 0.55 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 11 (52.4) | 15 (62.5) | 23 (71.9) | 0.35 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 9 (42.9) | 13 (54.2) | 17 (53.1) | 0.54 |

| Body Mass Index | 28.1 ± 1.3 | 27.7 ± 1.1 | 28.3 ± 1.1 | 0.89 |

| CAD ≥50% stenosis, n (%) | 9 (42.9) | 7 (29.2) | 12 (37.5) | 0.37 |

| Valvular disease, n (%) | 17 (81.0) | 20 (83.3) | 23 (71.9) | 0.38 |

| Congestive Heart Failure, n (%) | 5 (23.8) | 8 (33.3) | 11 (34.4) | 0.44 |

| Stroke history, n (%) | 2 (9.5) | 1 (4.2) | 1 (9.4) | 0.26 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 3 (14.3) | 2 (8.33) | 4 (12.5) | 0.90 |

| Median AF duration, months (IQR) | 0 (0–0) | 48 (3.5–85.5) | 60 (27–120) | 0.28 |

| Surgery Type | ||||

| Mitral valve replacement/repair | 14 (66.7) | 13 (54.2) | 17 (53.1) | 0.90 |

| Tricuspid valve replacement/repair | 4 (19.0) | 6 (25.0) | 8 (25.0) | 0.85 |

| Coronary artery bypass graft | 8 (38.1) | 5 (20.8) | 8 (25.0) | 0.24 |

| Maze procedure | 2 (9.5) | 21 (87.5) | 31 (96.9) | 1.1×10−7 |

| Echocardiographic Characteristics | ||||

| Mitral valve stenosis, n (%) | 2(9.5) | 2(8.3) | 4(12.5) | 0.19 |

| Mitral regurgitation, ≥2+, n (%) | 16 (76.2) | 13 (54.2) | 19 (59.4) | 0.23 |

| Tricuspid regurgitation, ≥2+, n (%) | 6 (28.6) | 8(33.3) | 14 (43.8) | 0.53 |

| Indexed LA diameter, cm/m2 | 2.38 ± 0.08 | 2.39 ± 0.11 | 2.5 ± 0.10 | 0.62 |

| Indexed LA volume, ml/m2 | 47.1 ± 3.99 | 58.1 ± 6.79 | 59.5 ± 5.33 | 0.27 |

| Indexed LA area (2 chamber, cm2/m2) | 11.79 ±0.89 | 14.21 ± 1.06 | 14.05 ± 0.81 | 0.16 |

| Indexed LA area (4 chamber, cm2/m2) | 13.1 ± 0.86 | 14.2 ± 1.16 | 15.5 ± 0.98 | 0.27 |

| Indexed Length (Apical shortest, cm/m2) | 2.81 ± 0.17 | 3.10 ± 0.16 | 3.16 ± 0.12 | 0.22 |

| # with known LA dimensions, n% | 19 (90.5) | 22 (91.7) | 30 (93.8) | 0.78 |

| Left ventricular ejection Fraction% | 52.7 ± 3.2 | 54.5 ± 2.1 | 50.5 ± 1.5 | 0.40 |

| Use of medications | ||||

| ACE inhibitors, ARBs | 8 (38.1) | 14 (58.3) | 14 (43.8) | 0.36 |

| Other diuretics* | 11 (52.4) | 11 (45.8) | 19 (59.4) | 0.66 |

| Beta blockers | 7 (33.3) | 11 (45.8) | 14 (43.8) | 0.60 |

| Statins | 2 (9.5) | 3 (12.5) | 3 (9.3) | 0.90 |

Values are mean ± SEM, unless indicated. AF: atrial fibrillation, CAD: coronary artery disease, LA: Left atria; ACE: angiotensin converting enzyme; ARBs: angiotensin-II receptor blockers. SR: sinus rhythm. ANOVA and Chi-square test was used to assess p value (SR vs. AF/AF) for continuous and categorical variables, respectively.

Other diuretics included thiazides and aldosterone antagonists, but not ACE inhibitors or ARBs.

ET-1 and AF status

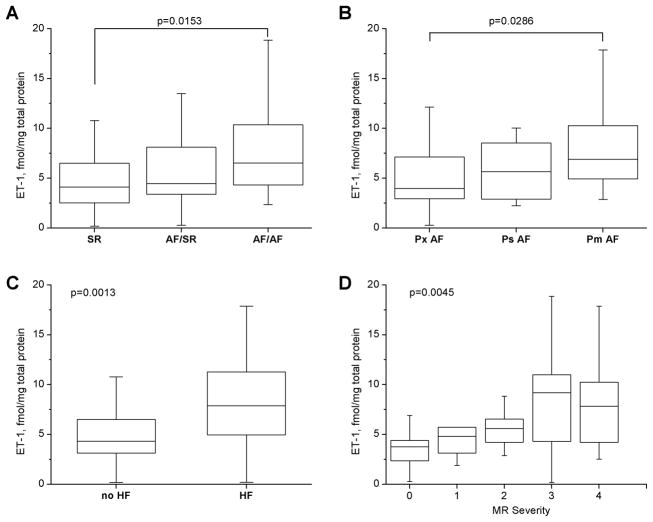

LAA ET-1 protein levels were evaluated in atrial homogenates. ET-1 content was greater in AF/AF patients than in SR patients (Median (IQR): 6.5 (4.3–10.4) vs. 4.1 (2.4–6.5) fmol/mg protein), p=0.0153/Kruskal-Wallis (Figure 1A). To further assess the relation of LAA ET-1 content to AF persistence, AF patients were sub-grouped into three matched sets: permanent AF (Pm), persistent AF (Ps), and paroxysmal AF (Px), (see Supplement, Table 1). Paroxysmal AF was defined as AF with spontaneous termination within 7 days. Persistent AF lasted more than 7 days and required cardioversion for restoration of sinus rhythm. Permanent AF was defined as long-lasting AF in which cardioversion was either contra-indicated or ineffective17. Permanent AF patients had a greater LAA ET-1 content than paroxysmal AF patients (median (IQR): 7.0 (4.9–10.4) vs. 3.96 (2.7–8.15) fmol/mg protein, p=0.0286/ Kruskal-Wallis, Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Left atrial ET-1 content in patients with structural cardiovascular diseases.

Box plots show median, 25th and 75th percentile values; whiskers indicate minimum and maximum values for LA ET-1 in SR, AF/SR or AF/AF patients at surgery (A); in Px (paroxysmal), Ps (persistent), Pm (permanent) AF (B, Kruskal-Wallis); and in heart failure (HF) or no HF (C, Mann-Whitney). Panel D is a box plot showing median values of LA ET-1 content in patients with mitral regurgitation (MR) of increased severity (0–4, Kruskal-Wallis). “r” is Spearman’s correlation coefficient.

Impact of cardiovascular disease on LAA ET-1 content

LAA ET-1 content was evaluated as a function of comorbid cardiovascular conditions. LAA ET-1 content was higher in HF patients (median (IQR): 4.3 (2.9–6.5) vs. 7.2 (4.6–10.8) fmol/mg protein, p=0.0013/Mann-Whitney test (Figure 1C), and as a function of MR severity, p=0.0045 (Figure 1D). Atrial ET-1was not correlated with left ventricular ejection fraction (Spearman’s r=−0.15, p=0.21). By univariate analysis, LAA ET-1 levels were similar between hypertensive and non-hypertensive patients (Median (IQR): 4.93 (3.79–9.7) vs. 5.1 (3.3–10.5) fmol/mg protein, p=0.35/Mann-Whitney test). By multivariate analysis, both MR severity and HF were associated with the square root of atrial ET-1. However, as MR severity and HF are also linearly correlated with iLAD (MR, r=0.60, p= 1.02×10−7; HF, r=0.294, p=0.0129), these parameters were not included in the final multivariate model. By step-wise analysis, CAD, diabetes, gender, BMI, use of beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors were not correlated with atrial ET-1, and thus were excluded from the final model. Multivariate analysis showed that, in addition to AF status, age, HTN and LA size were associated with square root of atrial ET-1 content (Table 2, R2=0.49, P=3.95×10−9, DF=65). Interestingly, this analysis revealed that statin-treated patients had lower LA ET-1 content than non-statin treated patients (p=0.05).

Table 2.

Multivariate factors associated with square root of left atrial ET-1 content

| Response = square root of ET-1 fmol/mg total protein Unadjusted R2= 0.5346, p=3.947×10−9 Adjusted R2= 0.4910 # of observations= 71, DF=65 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (slope, B) | Std error | P value | Standardized coefficient (β) | |

| Age, yrs | 0.0128 | 0.0059 | 0.034 | 2.17 |

| Male sex | −0.0168 | 0.0772 | 0.83 | −0.22 |

| AF status | 0.2833 | 0.0850 | 0.0014 | 3.33 |

| Hypertension | 0.1705 | 0.0614 | 0.0072 | 2.77 |

| Indexed LA diameter, cm/m2 | 0.7503 | 0.1434 | 1.98×10−6 | 5.23 |

| Use of statins | −0.2103 | 0.1057 | 0.051 | 1.99 |

AF status: (coded as SR=1, AF/SR=2, AF/AF=3), LA: Left atria. R2 is coefficient of determination. β is the standardized coefficient (slope/std error).

Determinants of LA size

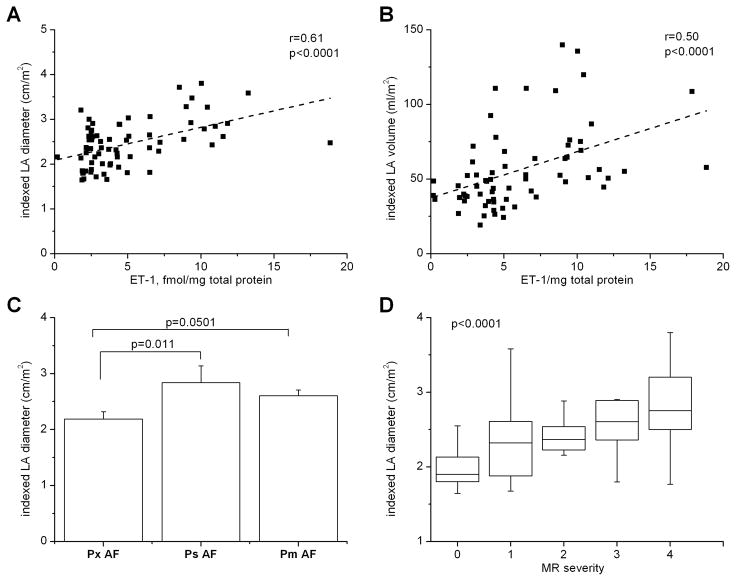

Echocardiographic data available from 71 patients was used to assess the relationships between atrial rhythm, LA size and LA ET-1 content. Atrial ET-1 content was positively correlated with LA size; patients with higher ET-1 levels had larger iLADs (Spearman’s r=0.61, p=1.08×10−7, Figure 2A) and iLAVs (Figure 2B, r=0.5, p=1.2×10−4). This relationship was further evaluated among rhythm groups. Patients in AF at surgery (AF/AF) showed a stronger correlation of atrial ET-1 content with iLAD (r=0.78, p=2.9×10−5) than the AF/SR group (r=0.62, p=0.0002). Intriguingly, no correlation was observed between atrial ET-1 level and iLAD among SR patients (r=0.24, p=0.39). As the groups were matched for other cardiovascular conditions, these data suggest that atrial rhythm modulates the relationship between LA ET-1 content and LA size. Because reentrant electrical activity depends on tissue mass, it is not surprising that AF persistence is also associated with iLAD (Figure 2C). Together, these data show that ET-1 is associated with the factors that underlie AF persistence.

Figure 2. Correlation of left atrial ET-1 with left atrial size in AF patients.

A, B) Scatter plots showing the relationship of LA ET-1 to indexed LA diameter (A) and to indexed LA volume (B); “r” is Spearman’s correlation coefficient. C) Relation of atrial ET-1 to severity of AF among patients with AF history. Px: paroxysmal, Ps: persistent, Pm: permanent AF (ANOVA). D) Box plots showing relation of mitral regurgitation (MR) severity to indexed LA diameter (Kruskal-Wallis).

Severity of MR was also strongly associated with increased iLAD (p=3.8×10−5, Kruskal-Wallis, Figure 2D) and iLAV (p=0.00016, Kruskal-Wallis). Multivariate analysis identified severity of MR and square root of atrial ET-1 as the strongest predictors of LA enlargement, as assessed by both iLAD (R2=0.51, p=4.67×10−10, DF=66, Table 3) and iLAV (R2=0.40, p=5.95×10−6, DF=62). Interestingly, female gender was positively correlated with iLAD (Table 3); however, the effect size was small. In our dataset, neither AF status nor history of HTN were significant univariate predictors of iLAD and were not included in multivariate regression models for iLAD. LA enlargement predicts mortality for HF patients. HF was a univariate predictor of both iLAD and atrial ET-1, and a predictor of iLAD by stepwise analysis; however, presence of ET-1 in the model masked this relation. Although MR severity and atrial ET-1 are related, both were strong predictors of iLAD in our multivariate model (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate predictors of left atrial size

| Response = Indexed LA diameter (cm/m2) Undjusted R2= 0.5452, p= 4.67×10−10 Adjusted R2= 0.5102 # of observations= 71, DF=65 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (slope, B) | Std error | P value | Standardized coefficient (β) | |

| Age, years | −0.00512 | 0.00399 | 0.201 | −1.29 |

| Female sex | 0.1027 | 0.0477 | 0.0350 | 2.15 |

| MR severity | 0.1244 | 0.0312 | 1.72×10−4 | 3.99 |

| Square root ET-1, fmol/mg protein | 0.2374 | 0.0642 | 4.47×10−4 | 3.70 |

| Heart Failure | 0.0759 | 0.0514 | 0.145 | 1.48 |

MR: Mitral regurgitation (coded as a continuous variable, 0–4); LA: Left atria, R2 is the coefficient of determination. Beta (β) is the standardized coefficient (slope/std error).

Sources of atrial ET-1

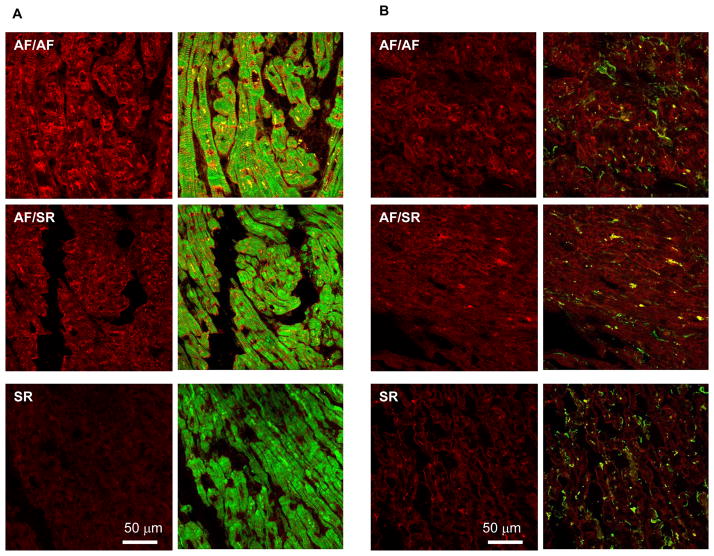

Although ET-1 is prominently produced by vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells9, ET-1 has also been reported to be produced by cardiac myocytes18 and fibroblasts19. Confocal microscopy (Figure 3) confirmed that atrial ET-1 staining (red) is detectable in both cardiac myocytes and in fibroblasts (green). Consistent with our biochemical results, the intensity of ET-1 staining was associated with atrial rhythm. ET-1 staining was heterogeneously distributed.

Figure 3. Distribution of ET-1 in atrial myocytes and fibroblasts of AF patients.

Representative confocal immunofluorescence images of LA sections from 3 patients: one in sinus rhythm (SR), one with AF history but in SR at surgery (AF/SR), and a patient in AF at surgery (AF/AF). Sections A were stained with ET-1 antibody (red) and phalloidin antibody to stain myocytes (green). Sections B were stained with the same ET-1 antibody (red) and with vimentin antibody to stain fibroblasts (green) (B). Each panel shows images representing ET-1 staining alone (red) or an overlay of ET-1 with phalloidin or vimentin (green).

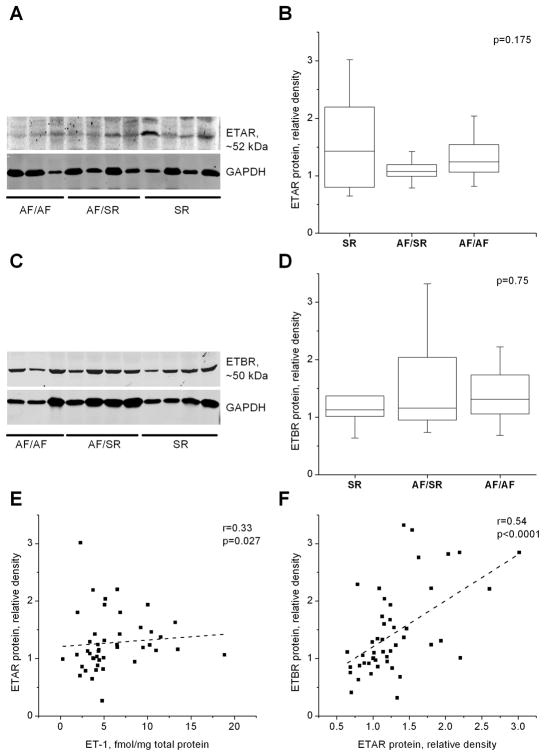

ET-1 receptor distribution and density in human AF

ET-1 receptor activity modulates intracellular signaling pathways that affect contractility, excitability and transcription. In a subset of 45 patients (9 SR, 14 AF/SR, and 21 AF/AF), western blot analysis was used to assess ET-1 receptor density (ETAR and ETBR) relative to GAPDH. ETAR and ETBR density did not differ between study groups (Kruskal-Wallis test). This finding was confirmed by multivariate analysis, adjusting for possible confounders (e.g. HF, HTN, MR, age, sex, LA size, CAD) (Figure 4A-D). Receptor distribution was also evaluated using immunohistochemistry. Confocal imaging showed no differences in ETAR distribution among the groups (Supplement, Figure 1). ETAR (green) was abundantly expressed in cardiac myocytes (red) and in fibroblasts (purple), with no obvious differences in receptor localization between groups. ETAR expression in cardiac myocytes was most apparent in the cell membrane and intercalated disk regions, with less cytosolic staining, and minimal localization in the nucleus (blue). In fibroblasts, ETAR was expressed in the cytosol and the nucleus (Supplement, Figure 1).

Figure 4. Endothelin receptor type A and B density among AF patients.

A and C show representative western blots of ETAR and ETBR proteins and GAPDH from left atrial appendage of patients with sinus rhythm (SR, n=9), with AF but SR at surgery (AF/SR, n=14) and in AF (AF/AF=22) at surgery. Panels B,D show box plots of receptor intensity relative to GAPDH of the blots in A and C by atrial rhythm (Kruskal-Wallis). Panels E,F are scatter plots showing relation of ETAR protein density with ET-1 protein and ETBR protein density, respectively. “r” is Spearman’s correlation coefficient.

In contrast to ETAR, distribution of ETBR (green) in cardiac myocytes was more cytosolic, and ETBR was more abundant in the nucleus. In fibroblasts, ETBR was expressed in the cytosol and the nucleus (Supplement, Figure 2).

LAA ET-1 content was weakly correlated with ETAR expression (Figure 4E), but not with ETBR expression, suggesting that ET-1 may modulate ETAR protein expression. Interestingly, ETAR protein expression was significantly correlated with ETBR protein expression (Figure 4F), suggesting that ET-1 independent mechanisms also modulate receptor expression.

Microarray Results

Microarrays facilitate simultaneous comparisons of mRNA levels for many different genes. Illumina HT-12 expression arrays were used to characterize mRNA expression profiles in LAA specimens from 205 patients, 66 of whom overlapped with those in Table 1, above. Table 4 summarizes clinical and demographic characteristics of these patients.

Table 4.

Patient population characteristics, mRNA expression array studies

| n= 205 | |

|---|---|

| Clinical Characteristics | |

| Age, years | 61.87±0.85 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 152 (74.0) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 114 (56.0) |

| Body Mass Index | 28.8±0.39 |

| History of AF | 162 (79.0) |

| CAD ≥50% stenosis, n (%) | 100 (49.0) |

| Valvular disease, n (%) | 91 (44.6) |

| Congestive Heart Failure, n (%) | 62 (30.0) |

| Stroke history, n (%) | 17 (8.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 34 (16.6) |

| Surgery Type | |

| Mitral valve replacement/repair | 71 (34.8) |

| Tricuspid valve replacement/repair | 22 (10.7) |

| Echocardiographic Characteristics | |

| Mitral regurgitation, ≥2+, n (%) | 135 (66.2) |

| Tricuspid regurgitation, >2+, n (%) | 104 (51.0) |

| Indexed LA diameter, cm/m2 | 2.37±0.04 |

| Left ventricular ejection Fraction (%) | 50.9±1 |

Values are expressed as mean ± SEM, unless otherwise indicated.

AF: atrial fibrillation; CAD: coronary artery disease; LA: Left atria.

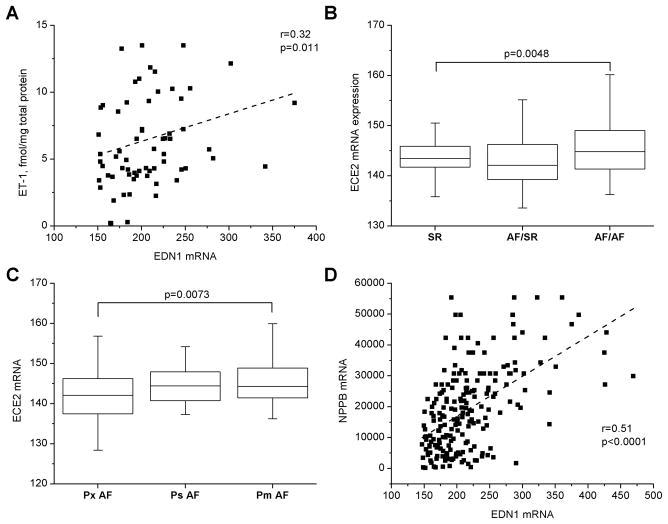

Atrial ET-1 protein content and mRNA levels (EDN1) were correlated (Spearman’s r=0.32, p=0.0108, Figure 5A), suggesting that the ET-1 protein detected has an atrial origin. As reported in the subset of patients with LAA ET-1 measurements (Figure 2A), EDN1 expression levels were also correlated, though more weakly, with iLAD (r=0.22, p=0.01). Interestingly, Figures 5B,C show that mRNA expression of endothelin converting enzyme (ECE2) was associated both with AF and with AF persistence, suggesting that ET-1 processing is activated during AF.

Figure 5. ET-1 gene expression and processing during AF.

Scatter plot show the relation of LA ET-1 mRNA (EDN1) to ET-1 protein; (A). Box plots show median, 25th and 75th percentile values; whiskers indicate minimum and maximum values for relation of LA endothelin converting enzyme 2 mRNA (ECE2) to rhythm (AF/AF vs. SR patients, B) and AF persistence (Pm>Ps>Px) (C); Kruskal-Wallis test. Panel D shows the relation of LA EDN1 to mRNA level of brain natriuretic peptide, NPPB. “r” is Spearman’s correlation coefficient.

Plasma BNP is a predictor of AF. In vitro, ET-1 has been reported to regulate atrial BNP expression. To assess whether this occurs in human atria, we evaluated the relationship between atrial ET-1 protein and mRNA (EDN1) with BNP mRNA (NPPB). EDN1 (Figure 5D) and ET-1 protein expression were both strongly correlated with NPPB expression. Atrial NPPB abundance was also associated with AF and HF (data not shown).

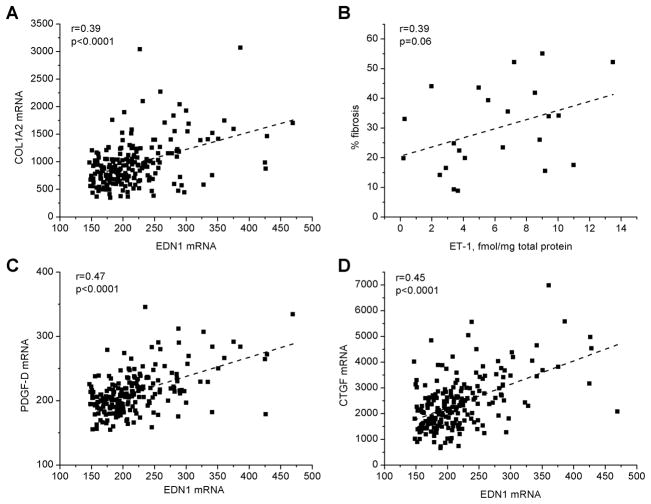

In addition to promoting myocyte hypertrophy, ET-1 can stimulate fibroblast proliferation and extracellular matrix deposition. Interstitial fibrosis (primarily composed of collagen) can be a critical element of the substrate for AF. We assessed the relationships between atrial ET-1 and collagen expression. The mRNA levels of collagen isoform 1 (Fig 6A), as well as collagen isoforms 3 and 4 were each positively correlated with atrial EDN1 (COL3A1: Spearman’s r=0.39, p=6.8×10−6 ; COL4A1: r=0.42, p=0.0023, respectively). In a subset of samples, quantitative image analysis of Masson’s trichrome stained sections documented a similar relationship between atrial ET-1 protein and collagen deposition (r=0.39, p=0.065, Figure 6B), suggesting a functional relationship between atrial ET-1 protein and development of atrial fibrosis.

Figure 6. ET-1 mRNA is associated with genes involved in cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis.

Panel A shows the relation of EDN1 to collagen isoform 1 mRNA expression (COL1A2). Panel B shows the relation of ET-1 protein to extent of fibrosis (as determined by quantitative analysis of Masson’s Trichrome stained LAA sections). Panels C, D show the relation of EDN1 mRNA abundance to platelet derived factor D (PDGFD) and CTGF mRNA. “r” is Spearman’s correlation coefficient.

Platelet derived growth factor (PDGF) signaling is implicated as a modulator of fibroblast proliferation. CTGF also promotes cardiac fibrosis, and is modulated by ET-1. Our microarray analysis suggests a coordinate regulation of both PDGF and CTGF expression by ET-1 (Figures 6C, D).

Discussion

Here we evaluated the hypothesis that atrial ET-1 is increased in AF and is associated with LA enlargement, atrial fibrosis and AF persistence in patients with structural heart disease. Consistent with earlier plasma studies14, we also found that LAA ET-1 protein levels were elevated in AF patients with HTN, HF, and MR – all conditions associated with increased hemodynamic stress. Myocyte hypertrophy and altered expression of several cardiac-specific genes are adaptive responses to hemodynamic stress. In experimental studies, ET-1 has been shown to modulate intracellular Ca2+ release20, induce cardiac myocyte hypertrophy10 and modulate fibroblast proliferation and extracellular matrix deposition8.

Local activation of atrial ET-1 in AF patients with structural heart disease

Plasma ET-1 levels are reported to be elevated in patients with diastolic dysfunction and elevated atrial pressures21. Although circulating levels of ET-1 were reported to be elevated in AF patients with underlying cardiac disease14, little is known about atrial ET-1 content or its relevance to atrial pathophysiology. In a small study, pro-ET-1 mRNA and protein expression were evaluated in right atrial samples from patients with and without valvular disease, in sinus rhythm or in AF22. Atrial ET-1 was increased with AF only in the subset with underlying valve disease. In patients with mitral valve disease, LA enlargement is profound, and LA dilatation is associated with poor clinical prognosis4. No studies have assessed the impact of AF or structural heart disease on LA ET-1 content or receptor expression.

Here we report that LA ET-1 protein is elevated in AF patients with underlying cardiac disease, and that elevated ET-1 levels are associated with AF rhythm and persistence. Atrial rhythm was an important determinant of LA ET-1 content, and we documented an increased abundance of both ET-1 protein and mRNA in the fibrillating LA. This may bedue to the elevated wall stress associated with AF and atrial dilatation. Although there was a trend for a reduction of LAA ETAR protein in AF patients (Figure 5A,B), no significant differences in ET-1 receptor expression were detected between rhythm groups. Although modulation of ETAR by ET-1 was not strong, ETAR expression was significantly correlated with ETBR protein expression. ETAR and ETBR have opposing effects on blood pressure9; the nuclear localization of ETBR may suggest a greater impact on transcriptional regulation. These data suggest a complex relationship between agonist concentration and receptor subtype distribution; ET-1 receptor expression may be regulated in an ET-1 independent manner.

The LA is frequently dilated in HF patients, even among those with preserved LV ejection fraction23. Development of AF in patients with MR is independently associated with HF and death24. HTN is also an important risk factor for AF1. Here we report that increased LAA ET-1 is associated with each of these conditions in AF patients, and that this relationship is modulated by atrial rhythm. Using confocal microscopy, we show that ET-1 is present in both atrial myocytes and fibroblasts. By modulating blood pressure, left atrial myocyte Ca2+ handling, fibroblast proliferation, cardiac hypertrophy and the activation of cardiac specific gene programs, ET-1 may exacerbate cardiac dysfunction and accelerate the development or progression of HF and AF.

Atrial ET-1 content and left atrial geometry

Atrial structural remodeling is observed in clinical AF and in experimental AF models8. LA enlargement is a marker of diastolic dysfunction25 and an independent predictor for development of post-operative AF3, stroke and morbidity26. In a murine study, cardiac-specific overexpression of ET-1 promoted atrial and ventricular hypertrophy, dysfunction, dilatation, inflammation and fibrosis27, leading to dilated cardiomyopathy and impaired survival. LA size increases in response to both increased left ventricular filling pressure and mitral regurgitation24. Patients with MVD have an increased risk of developing AF. Independent risk factors for AF in MVD were an age >65 years and a baseline LA size greater than 5 cm24. Here, we demonstrate that atrial ET-1 levels are strongly correlated with both LA size and MR severity.

ET-1 and Atrial Fibrosis

The PDGF8 and CTGF28 signaling pathways are prominent modulators of cardiac fibrosis, and fibrosis is an important determinant of AF persistence32. Atrial fibroblasts are reported to be more sensitive than ventricular fibroblasts to a variety of pro-fibrotic stimuli, including PDGF and ET-18. ET-1 mRNA levels were strongly associated with expression of PDGFD and its B type receptor mRNA (data not shown), and with CTGF. These associations are likely functionally significant, as both ET1 protein and mRNA levels were associated with increased expression of the major cardiac collagen isoforms, and with atrial fibrosis. Here, patients with permanent AF had higher atrial ET-1 levels and larger LA than those with paroxysmal AF, suggesting that AF persistence may be modulated by ET-1 production. By accelerating the development of atrial fibrosis and dilatation, ET-1 may contribute to the structural remodeling that is characteristic of persistent and permanent AF29.

ET-1 expression is modulated at both transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. In AF patients, both mRNA and protein levels of ET-1 were elevated. Increased endothelin converting enzyme mRNA expression suggests that processing of atrial ET-1 may be enhanced in AF.

In recent studies, plasma levels of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) have also been shown to predict the development of AF30 and post operative AF31. Both BNP and ET-1 expression are enhanced by hemodynamic stress11,32. It is intriguing that atrial, but not ventricular, BNP expression is modulated by ET-132. Thus, whether BNP is a marker or a mediator of AF risk is unclear. Our data show that atrial expression of BNP mRNA was strongly associated with ET-1 mRNA and protein levels. Although speculative, the prognostic value of plasma BNP as a predictor of AF30 may depend on this relationship.

Study Limitations

A primary limitation of our study is the limited number of subjects. Ascertainment of rhythm history is challenging in surgical patients; misclassification of patients (with respect to rhythm history) would tend to minimize differences between groups. Although this study demonstrates an association of LAA ET-1 content with LA size in AF patients with underlying cardiovascular diseases, it cannot prove a causal role of ET-1 as a mediator of LA hypertrophy, dilatation, fibrosis or AF persistence.

Conclusions

LA dilatation is enhanced by AF in subjects with concomitant structural heart disease. Increased LAA ET-1 is associated with and may contribute to increased AF persistence and LA dilatation. Our data suggest that both ET-1 gene expression and processing are activated during AF. ET-1, in turn, enhances expression of genes involved in cardiac dilatation, hypertrophy, and fibrosis. The combined influence of these factors may contribute to the impact of ET-1 on AF persistence. Our study suggests that increased expression of atrial ET-1 is associated with the progression of atrial dysfunction. Thus, interventions that decrease atrial ET-1 expression (e.g., statins, etc.) or block its receptors might be useful in slowing the progression of AF.

Pharmacologic strategies for treating AF are frequently directed at rhythm control and are mostly ineffective. Numerous studies have focused on the role of angiotensin-II as a modulator of atrial electrical and structural remodeling. In experimental studies, angiotensin receptor blockade is insufficient to prevent the development atrial fibrosis in the setting of ventricular dysfunction. Endothelin-1 signaling may be a target for AF-focused therapeutic interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This work was supported by the Atrial Fibrillation Innovation Center, a Wright Center Initiative of the State of Ohio; the Fondation Leducq European-North American Atrial Fibrillation Research Alliance; and the National Institutes of Health, RO1 HL090620 (M.K.C., J.B., D.V.W.).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Haft JI, Teichholz LE. Echocardiographic and clinical risk factors for atrial fibrillation in hypertensive patients with ischemic stroke. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:1348–1351. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neuberger HR, Mewis C, van Veldhuisen DJ, Schotten U, van Gelder IC, Allessie MA, Bohm M. Management of atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2568–2577. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manning WJ, Gelfand EV. Left atrial size and postoperative atrial fibrillation: the volume of evidence suggests it is time to break an old habit. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:787–789. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abhayaratna WP, Seward JB, Appleton CP, Douglas PS, Oh JK, Tajik AJ, Tsang TS. Left atrial size: physiologic determinants and clinical applications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:2357–2363. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerdts E, Oikarinen L, Palmieri V, Otterstad JE, Wachtell K, Boman K, Dahlof B, Devereux RB. Correlates of left atrial size in hypertensive patients with left ventricular hypertrophy: the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension (LIFE) Study. Hypertension. 2002;39:739–743. doi: 10.1161/hy0302.105683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailey GW, Braniff BA, Hancock EW, Cohn KE. Relation of left atrial pathology to atrial fibrillation in mitral valvular disease. Ann Intern Med. 1968;69:13–20. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-69-1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohtani K, Yutani C, Nagata S, Koretsune Y, Hori M, Kamada T. High prevalence of atrial fibrosis in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:1162–1169. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burstein B, Libby E, Calderone A, Nattel S. Differential behaviors of atrial versus ventricular fibroblasts: a potential role for platelet-derived growth factor in atrial-ventricular remodeling differences. Circulation. 2008;117:1630–1641. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.748053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Russell FD, Molenaar P. The human heart endothelin system: ET-1 synthesis, storage, release and effect. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2000;21:353–359. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01524-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamashita K, Discher DJ, Hu J, Bishopric NH, Webster KA. Molecular regulation of the endothelin-1 gene by hypoxia. Contributions of hypoxia-inducible factor-1, activator protein-1, GATA-2, AND p300/CBP. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12645–12653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011344200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macarthur H, Warner TD, Wood EG, Corder R, Vane JR. Endothelin-1 release from endothelial cells in culture is elevated both acutely and chronically by short periods of mechanical stretch. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;200:395–400. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hasdai D, Holmes DR, Jr, Garratt KN, Edwards WD, Lerman A. Mechanical pressure and stretch release endothelin-1 from human atherosclerotic coronary arteries in vivo. Circulation. 1997;95:357–362. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.2.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Brien DW, Fu Y, Parker HR, Chan SY, Idikio H, Scott PG, Jugdutt BI. Differential morphometric and ultrastructural remodelling in the left atrium and left ventricle in rapid ventricular pacing-induced heart failure. Can J Cardiol. 2000;16:1411–1419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tuinenburg AE, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Boomsma F, Van Den Berg MP, De Kam PJ, Crijns HJ. Comparison of plasma neurohormones in congestive heart failure patients with atrial fibrillation versus patients with sinus rhythm. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81:1207–1210. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00092-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masson S, Latini R, Anand IS, Barlera S, Judd D, Salio M, Perticone F, Perini G, Tognoni G, Cohn JN. The prognostic value of big endothelin-1 in more than 2,300 patients with heart failure enrolled in the Valsartan Heart Failure Trial (Val-HeFT) J Card Fail. 2006;12:375–380. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, Picard MH, Roman MJ, Seward J, Shanewise JS, Solomon SD, Spencer KT, Sutton MS, Stewart WJ. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:1440–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Staszewski J. Atrial fibrillation characteristics in patients with ischaemic stroke. Kardiol Pol. 2007;65:751–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tonnessen T, Christensen G, Oie E, Holt E, Kjekshus H, Smiseth OA, Sejersted OM, Attramadal H. Increased cardiac expression of endothelin-1 mRNA in ischemic heart failure in rats. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;33:601–610. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(96)00266-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abraham D, Dashwood M. Endothelin--role in vascular disease. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:v23–24. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Russell JA, Roberts JM. Functional antagonism in rabbit pulmonary veins contracted by endothelin. Pulm Pharmacol. 1991;4:67–72. doi: 10.1016/0952-0600(91)90054-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng CP, Ukai T, Onishi K, Ohte N, Suzuki M, Zhang ZS, Cheng HJ, Tachibana H, Igawa A, Little WC. The role of ANG II and endothelin-1 in exercise-induced diastolic dysfunction in heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H1853–1860. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.4.H1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brundel BJ, Van Gelder IC, Tuinenburg AE, Wietses M, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Van Gilst WH, Crijns HJ, Henning RH. Endothelin system in human persistent and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12:737–742. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rossi A, Cicoira M, Florea VG, Golia G, Florea ND, Khan AA, Murray ST, Nguyen JT, O’Callaghan P, Anand IS, Coats A, Zardini P, Vassanelli C, Henein M. Chronic heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: diagnostic and prognostic value of left atrial size. Int J Cardiol. 2006;110:386–392. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grigioni F, Avierinos JF, Ling LH, Scott CG, Bailey KR, Tajik AJ, Frye RL, Enriquez-Sarano M. Atrial fibrillation complicating the course of degenerative mitral regurgitation: determinants and long-term outcome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:84–92. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01922-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geske JB, Sorajja P, Nishimura RA, Ommen SR. The relationship of left atrial volume and left atrial pressure in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: an echocardiographic and cardiac catheterization study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:961–966. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Vaziri SM, D’Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Wolf PA. Independent risk factors for atrial fibrillation in a population-based cohort. The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA. 1994;271:840–844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang LL, Gros R, Kabir MG, Sadi A, Gotlieb AI, Husain M, Stewart DJ. Conditional cardiac overexpression of endothelin-1 induces inflammation and dilated cardiomyopathy in mice. Circulation. 2004;109:255–261. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000105701.98663.D4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Recchia AG, Filice E, Pellegrino D, Dobrina A, Cerra MC, Maggiolini M. Endothelin-1 induces connective tissue growth factor expression in cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;46:352–359. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Allessie MA. Atrial electrophysiologic remodeling: another vicious circle? J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1998;9:1378–1393. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1998.tb00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patton KK, Ellinor PT, Heckbert SR, Christenson RH, Defilippi C, Gottdiener JS, Kronmal RA. N-Terminal Pro-B-Type Natriuretic Peptide Is a Major Predictor of the Development of Atrial Fibrillation. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Circulation. 2009;120:1768–1774. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.873265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wazni OM, Martin DO, Marrouche NF, Latif AA, Ziada K, Shaaraoui M, Almahameed S, Schweikert RA, Saliba WI, Gillinov AM, Tang WH, Mills RM, Francis GS, Young JB, Natale A. Plasma B-type natriuretic peptide levels predict postoperative atrial fibrillation in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Circulation. 2004;110:124–127. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000134481.24511.BC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Magga J, Vuolteenaho O, Marttila M, Ruskoaho H. Endothelin-1 is involved in stretch-induced early activation of B-type natriuretic peptide gene expression in atrial but not in ventricular myocytes: acute effects of mixed ET(A)/ET(B) and AT1 receptor antagonists in vivo and in vitro. Circulation. 1997;96:3053–3062. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.9.3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.