Abstract

Na+ binding to thrombin enhances the procoagulant and prothrombotic functions of the enzyme and obeys a mechanism that produces two kinetic phases: one fast (in the μs time scale) due to Na+ binding to the low activity form E to produce the high activity form E:Na+, and another considerably slower (in the ms time scale) that reflects a pre-equilibrium between E and the inactive form E*. In this study we demonstrate that this mechanism also exists in other Na+-activated clotting proteases like factor Xa and activated protein C. These findings, along with recent structural data, suggest that the E*-E equilibrium is a general feature of the trypsin fold.

Keywords: Thrombin, activated protein C, factor Xa, Na+ binding, rapid kinetics, E* form

Introduction

Activation of trypsin-like proteases requires proteolytic processing of an inactive zymogen precursor 1 that occurs at the identical position in all known members of the family, i.e., between residues 15 and 16 (chymotrypsinogen numbering). The nascent N-terminus induces conformational change in the enzyme through formation of an ion-pair with the highly conserved Asp194 that organizes both the oxyanion hole and substrate binding cleft 2,3. Existing structures of the zymogen forms of trypsin 3, chymotrypsin 4 and chymase 5 document the lack of ion-pair interaction between Asp194 and the N-terminus of the catalytic chain. The zymogen→protease conversion is classically associated with the onset of catalytic activity 6,7 and provides a useful paradigm for understanding key features of protease function and regulation.

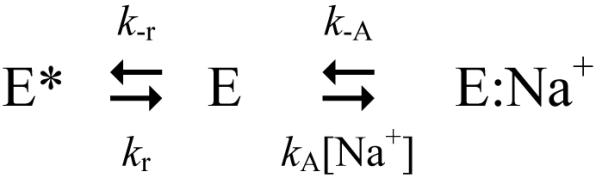

Recent structural and functional work on thrombin, a trypsin-like protease involved in blood coagulation 8, has added complexity to this widely accepted scenario. Thrombin is a Na+-activated protease for which Na+ binding significantly enhances activity toward synthetic and physiological substrates. The interaction of Na+ with thrombin is physiologically relevant and promotes cleavage of the substrates fibrinogen and PAR1 9-11, coagulation factors V 12, VIII 13 and XI 14, but has no effect on activation of the anticoagulant protein C 10,11, which makes Na+ an exquisite procoagulant/prothrombotic cofactor of thrombin. Indeed, several naturally occurring mutations like prothrombin Frankfurt (E146A) 15, Salakta (E146A) 16, Greenville (R187Q) 17, Scranton (K224T) 18, Copenhagen (A190V) 19 and Saint Denis (D221E) 20 that affect residues linked to Na+ binding 21 are associated with bleeding. Furthermore, anticoagulant thrombin mutants have been engineered rationally by perturbing the Na+ site 11,22-26. Investigation of the kinetic mechanism of Na+ binding has led to the discovery of a key allosteric equilibrium that involves the free enzyme 27. Na+ binding to thrombin is not a simple one-step process but gives rise to two kinetic phases, one fast (in the μs time scale) due to Na+ binding to E to produce E:Na+ 27,28 and another considerably slower (in the ms time scale) that reflects a pre-equilibrium between E and E* according to the kinetic scheme 8,27,29 The Na+-free form of thrombin, originally defined as the “slow” form 30, is not a single species or equivalently an ensemble of species in rapid equilibrium but a mixture of E* and E that interconvert with kinetic rate constants kr and k−r. Of these forms, E interacts with Na+ with a rate constant kA to populate the Na+-bound form E:Na+, originally defined as the “fast” form 30, that may dissociate into the parent components with a rate constant k−A. Na+ binds to a site between the 186- and 220- loops, located >15 Å away from residues of the catalytic triad 21,31, and converts the low activity E form to the high activity E:Na+ form. The E* form, on the other hand, is inactive and cannot bind Na+ or substrate to the active site 27,32. Recent alternative models of thrombin allostery 33-36 show considerable confusion about the nature of the slow form, which is defined as E*, zymogen-like, inactive or as a continuum of zymogen-like states 33-36, deny the existence of the low activity E form and basically predict a one-step kinetic mechanism for Na+ binding, with the enzyme transitioning directly from an inactive Na+-free form to the active Na+-bound form. These alternative models of thrombin allostery fail to account mathematically for the kinetic mechanism of Na+ binding and activation, as we have shown repeatedly 8,29,37, and are directly refuted by the kinetic mechanism in scheme 1. Existence of the active E form is strongly supported by kinetic 29,30 and structural 21,38-40 data. Under physiological conditions, E* only makes a minuscule (<1%) contribution to the E*-E-E:Na+ equilibria that are dominated by the active forms E (40%) and E:Na+ (60%) 27. E* becomes appreciably populated only at temperatures <25 °C and in the absence of Na+, or as a result of specific mutations 26,29,41.

SCHEME 1.

All three forms of thrombin have been identified crystallographically. Distinguishing features of E* are the collapse of the 215-217 segment into the active site that brings the highly conserved W215 in contact with the catalytic H57, a flip of the peptide bond between residues E192 and G193 that disrupts the oxyanion hole, and disorder in the 186- and 220- loops that perturbs the Na+ binding environment 26,29,42,43. The collapse of W215 into the active site precludes access of substrate to the primary specificity pocket and explains, along with perturbation of the Na+ binding site, why E* is an inactive form unable to interact with substrate or Na+. In the active E and E:Na+ forms the side chain of W215 is positioned >10 Å away from the catalytic H57 on the opposite side of the active site cleft, the active site is widely accessible to substrate and the 186- and 220- loops are ordered and correctly positioned for Na+ coordination 21. Small but significant differences exist between E and E:Na+. In the E form, the H-bond between the catalytic S195 and H57 is weakened or broken, the side chain of D189 in the primary specificity pocket is slightly shifted away from the optimal position for coordination of the Arg residue of an incoming substrate and polar interactions between the 186- and 220- loops in the Na+ binding site are weakened. An additional important difference between E and E:Na+ has been identified recently and involves the E192-G193 peptide bond that is flipped in the E form, leading to disruption of the oxyanion hole 29, as also documented in a structure of thrombin free of Na+ 44.

Na+ binding is a property of other vitamin K-dependent clotting proteases like factors VIIa, IXa, Xa and activated protein C that share high sequence homology with thrombin and carry the necessary Tyr residue at position 225 45,46. Structural identification of the Na+ binding site of thrombin using Rb+ replacement 31 has facilitated the subsequent identification of the analogous Na+ binding sites in factors Xa 47,48, VIIa 49 and activated protein C 50. Several groups have shown that Na+ has a significant influence on the activity of factor Xa 51-57 and activated protein C 58-62, but a modest effect on the properties of factor VIIa 45,63. In the case of factor IXa, structural evidence of Na+ binding remains controversial 64, but the effect of Na+ on the kinetic properties of the enzyme is well established 45,65. The physiological role of Na+ in these proteases remains largely unexplored 66. There is currently no structural information as to whether these enzymes partition among E*, E and E:Na+ forms like thrombin and no kinetic information on the mechanism of Na+ binding that would clarify the generality of the results reported for thrombin. In this study we present evidence that activated protein C and factor Xa bind Na+ through a mechanism that is identical to that of thrombin, thereby supporting the generality of the E*-E equilibrium.

Experimental Methods

Human thrombin was expressed and purified to homogeneity as reported elsewhere 21. Gla-domainless activated protein C was expressed using an HPC4-modified pRc/RSVvector (a gift from Dr. A. Rezaie) using a baby hamster kidney cell line. Purification and activation were carried out as described 67. Human factors Xa was obtained from Hematologic Technologies Inc (Essex Junction, VT).

Stopped-flow fluorescence measurements over a time range of 250 ms were carried out with an Applied Photophysics SX20 spectrometer, with excitation at 280 nm and a cutoff filter at 305 nm 27. Samples of the protein at a final concentration of 100 nM in a buffer of 50 mM Tris, 0.1% PEG8000, pH 8.0 at 15 °C were mixed with an equal volume (60 μl) of buffer containing variable amounts of NaCl, with a final concentration of NaCl in the 0-200 mM range. Due to the inhibitory effect of choline chloride (ChCl) on factor Xa because of specific binding of the cation to the active site of the enzyme 54,68,69, this salt was not used to maintain the ionic strength constant as done previously for studies on thrombin 27 and the Na+ concentration was changed by increasing the concentration of NaCl in the buffer. Stopped-flow measurements of Na+ binding to thrombin run under conditions where the ionic strength was not kept constant with ChCl yield results comparable to those run under conditions of constant ionic strength (see Results).

The total fluorescence change observed upon Na+ binding obeys the expression 27

| (1) |

where F0 and F1 are the values of F at [Na+]=0 and [Na+]=∞, and

| (2) |

is the apparent Na+ binding affinity that depends on the intrinsic Na+ binding affinity and the equilibrium constant for the E*-E interconversion . The value of r is derived from the dependence of the rate constant of the slow phase of fluorescence increase upon Na+ binding due to the E*-E interconversion. Scheme 1 leads to the set of differential equations

| (3) |

The two non-zero eigenvalues associated with the 3×3 matrix of kinetic rate constants in eq 3 are

| (4) |

and define the rates associated with the time evolution of [E*], [E] and [E:Na+]. Under conditions of separation of time scales, where Na+ binding and dissociation are much faster than the rates for the E*-E interconversion, the two eigenvalues in eq 4 generate the rate constants

| (5) |

| (6) |

The value of kfast is too fast to resolve by stopped-flow and requires the use of ultra-rapid kinetic methods 28. The value of kslow corresponds to the kobs of the slow exponential phase and is expected to decrease hyperbolically with increasing [Na+] from kr+k−r ([Na+]=0) to kr ([Na+]=∞), thereby yielding kr, k−r and KA.

Results

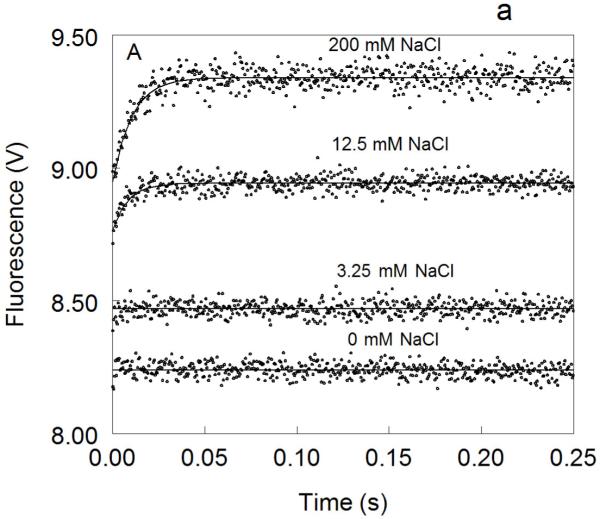

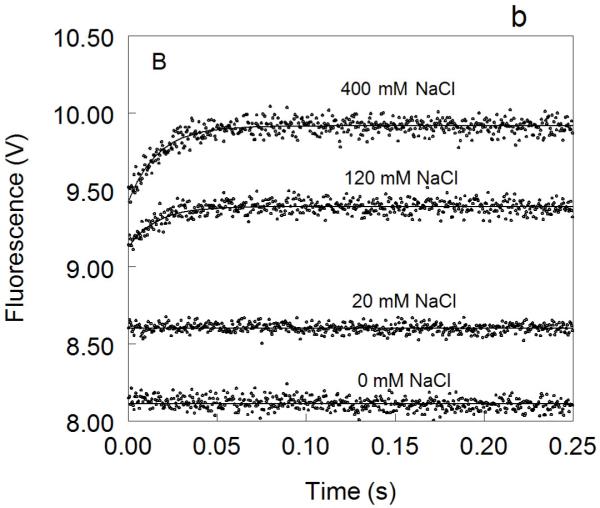

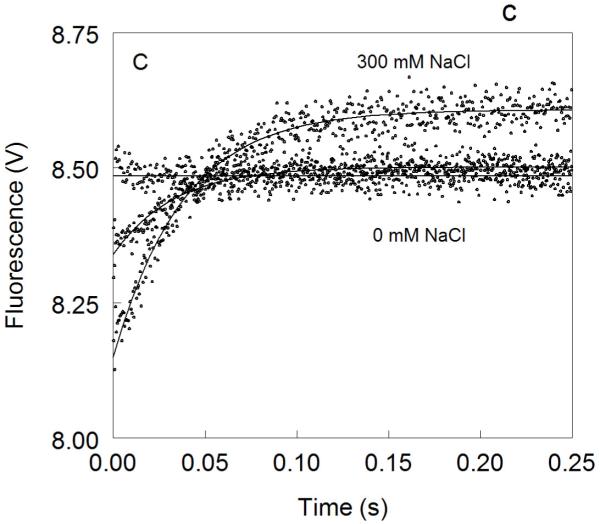

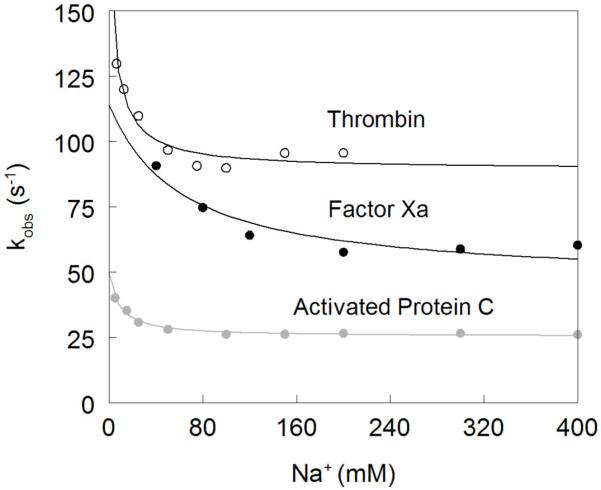

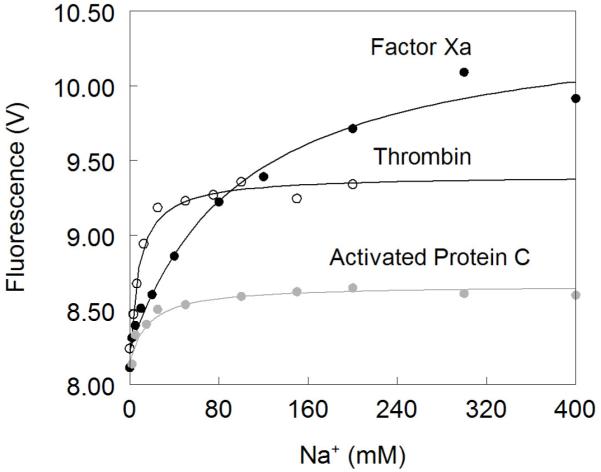

Na+ binding to thrombin gives rise to a biphasic increase in intrinsic fluorescence (Figure 1) as reported previously 27. A fast phase of increase evolves within the dead time (0.5 ms) of the spectrometer. The slow phase obeys a single exponential with kobs decreasing hyperbolically with [Na+] as predicted from eq 6 (Figure 2). Analysis of kobs for the slow phase yields values of kr=89±2 s−1 , k−r=85±9 s−1 and KA=160±30 M−1 (Table 1), in agreement with the results reported recently under conditions of constant ionic strength 27. The value of r=0.95±0.09 confirms that E* and E are equally populated in the absence of Na+ at 15 °C.

Figure 1. Kinetic traces of Na+ binding to thrombin (A), factor Xa (B) and activated protein C (C).

In all cases binding of Na+ obeys a two-step mechanism, with a fast phase completed within the dead time (<0.5 ms) of the spectrometer, followed by a single-exponential slow phase. The kobs for the slow phase decreases with increasing [Na+] (see also Fig. 2). Experimental conditions are: 100 nM enzyme, 50 mM Tris, 0.1% PEG8000, pH 8.0, at 15 °C. Continuous lines were drawn using the expression b-aexp(−kobst) with best-fit parameters: (A) a=0.000±0.000 V, b=8.239±0.001 V (0 mM Na+); a=0.000±0.000 V, b=8.470±0.001 V (3.25 mM Na+); a=0.175±0.002 V, kobs =120±4 s−1 , b=8.942±0.001 V (12.5 mM Na+); a=0.392±0.001 V, kobs=96±1 s−1 , b=9.340±0.002 V (200 mM Na+). (B) a=0.000±0.000 V, b=8.112±0.001 V (0 mM Na+); a=0.000±0.000 V, b=8.601±0.001 V (20 mM Na+); a=0.261±0.002 V, kobs=64±4 s−1 , b=9.391±0.001 V (120 mM Na+); a=0.488±0.001 V, kobs=60±1 s−1 , b=9.915±0.002 V (400 mM Na+). (C) a=0.000±0.000 V, b=8.485±0.001 V (0 mM Na+); a=0.162±0.001 V, kobs=31±1 s−1 , b=8.501±0.001 V (curve in the middle not labeled, 25 mM Na+); a=0.458±0.001 V, kobs =27±1 s−1 , b=8,608±0.001 V (300 mM Na+). The concentration of Na+ was changed in all cases by adding NaCl without keeping the ionic strength constant. The amplitude of the slow phase for factor Xa and activated protein C becomes less pronounced in the presence of Ca2+ (data not shown), reflecting the positive linkage between Na+ and Ca2+ binding in these proteases 51,52,54-58. Binding of Ca2+ likely shifts the E*-E equilibrium in favor of E. In the case of thrombin, Ca2+ has no effect on Na+ binding.

Figure 2. Na+ dependence of the kobs of the slow phase of Na+ binding to thrombin (open circles), factor Xa (black circles) and activated protein C (grey circles).

The values were obtained from analysis of the kinetic traces (see also Figure 1) and analyzed according to eq 6 in the text with best-fit parameter values listed in Table 1. Note how kobs features an inverse hyperbolic dependence on [Na+], thereby proving the existence of the E*-E equilibrium preceding Na+ binding. This demonstrates directly that the Na+-free slow form of thrombin is not a single species or a single ensemble of species, contrary to the basic assumption of alternative models of thrombin allostery 33-36. The Na+ affinity is highest for thrombin and lowest for factor Xa. The rate constants pertaining to the E*-E interconversion are fastest for thrombin and slowest for activated protein C, However, the value of the equilibrium constant r=k−r/kr is comparable for all enzymes, supporting the conclusion that the distribution of E* and E forms is conserved among different trypsin-like proteases.

Table 1.

Parameters for Na+ binding to thrombin, factor Xa and activated protein C

In the case of factor Xa, the observed response to Na+ binding is biphasic as seen for thrombin, but with some important differences (Figure 1). The total increase in fluorescence is significantly more pronounced (27% vs 15%) (Figure 3) and the dependence of kobs for the slow phase on [Na+] (Figure 2) reveals a significantly weaker Na+ affinity (KA=16±4 M−1) and slightly slower rates of E*-E interconversion (kr=45±4 s−1 , k−r=70±10 s−1). Both the large total fluorescence change and weak Na+ affinity were reported in previous studies 51,52,70. The value of r=1.5±0.2 for FXa is slightly higher than that of thrombin and underscores a larger contribution of E* to the E*-E equilibrium at 15 °C.

Figure 3. Na+ binding to thrombin (open circles), factor Xa (black circles) and activated protein C (grey circles).

Na+ binding curves were obtained from the total change in intrinsic fluorescence determined by stopped-flow kinetics. Experimental conditions are: 100 nM enzyme, 50mM Tris, 0.1% PEG8000, pH 8.0, at 15 °C. Continuous lines were drawn according to eq 1 in the text with best-fit parameter values listed in Table 1. Note how the Na+ affinity is highest for thrombin and lowest for factor Xa, which however shows the largest change in intrinsice fluorescence upon Na+ binding.

The behavior of activated protein C deserves attention. Na+ binding to activated protein C has been difficult to monitor by intrinsic fluorescence due to the weak amplitude of the response 70,71 (Figure 3). This puzzling observation has always been at odds with the sharp increase in amidolytic activity of activated protein C in the presence of Na+ 45,58-62,71,72. Analysis of Na+ binding to activated protein C by rapid kinetics reveals a simple and important explaination for the modest total fluorescence change. Na+ binding elicits a biphasic response for activated protein C as seen for thrombin and factor Xa, but the fast phase has a negative amplitude that opposes the positive contribution coming from the slow phase (Figure 1). The peculiar negative amplitude for the fast phase is likely due to a drastically different environment of the major fluorophores of activated protein C compared to thrombin and factor Xa, but conclusive answers can only come from systematic mutagenesis of Trp residues of activated protein C as done for thrombin 27. The net result given by the sum of the two phases is a total fluorescence change of small amplitude (Figure 3), with all the relevant information on Na+ binding being confined to a transient within the first 50 ms of the reaction. The traces in Figure 1 leave little doubt about the interaction of Na+ with activated protein C and support the existence of the allosteric E*-E equilibrium. In fact, analysis of kobs for the slow phase shows an inverse hyperbolic dependence on [Na+] (Figure 2) with values of kr=25±1 s−1, k−r=24±3 s−1 and KA=120±10 M−1. The Na+ binding affinity of activated protein C is comparable to that of thrombin and so is the value of r=0.95±0.08. However, the rates for the E*-E interconversion are significantly slower. These findings reveal important new information on Na+ binding to factor Xa and activated protein C that have eluded experimentalists for over three decades.

DIscussion

Demonstration of the existence of the E*-E equilibrium has significant implications for factor Xa. This enzyme catalyzes the conversion of prothrombin into thrombin with the assistance of factor Va, Ca2+ and phospholipids, altogether defining the prothrombinase complex 73. Prothrombin is composed of a Gla domain, two kringle domains and the serine protease catalytic domain. The prothrombinase complex converts prothrombin to the mature enzyme along two pathways by cleaving sequentially at R271 and R320 (prothrombin numbering). Initial cleavage at R320 (R15 in the chrymotrypsin numbering) between the A and B chains is the preferred pathway under physiological conditions and generates the active intermediate meizothrombin by triggering formation of the I16-D194 ion-pair, structuring of the active site and oxyanion hole 74. The alternative initial cleavage at R271 sheds the Gla domain and the two kringles and generates the inactive precursor prethrombin-2 with the R15-I16 peptide bond intact. The precise mechanism of thrombin generation by the prothrombinase complex remains highly controversial, with opposing models postulating existence of two interconverting functional forms of prothrombinase 75 or of the substrate prothrombin 76,77, each favoring one of the two possible cleavages. Pedersen has recently cast doubts on the mathematical rigor of these models 78 and added renewed concerns about their conceptual validity. The results presented here demonstrate that factor Xa is capable of alternative conformations due to Na+ binding and the E*-E equilibrium. The existing model of prothrombinase assuming different conformations of the enzyme directing cleavage at the two possible sites 75 should be refined to include the effects of Na+ and of the E*-E equilibrium on the kinetics of prothrombin cleavage. Given the modest Na+ affinity of factor Xa (Figure 3), it is unlikely that the enzyme exists in vivo in a form that is saturated with the cation. If would be of much interest to establish if the E and E:Na+ forms of factor Xa play different roles in cleavage at R320 or R271. The role of E* for factor Xa also needs attention, though this conformation may be transiently shifted to E upon interaction with other components of the prothrombinase complex and Ca2+. The conformational plasticity of factor Xa, partitioning among E*, E and E:Na+ forms, calls into question the main tenet of the alternative model of prothrombinase action where only the substrate prothrombin is assumed to exist in different conformations 76,77. On the other hand, conformational plasticity of the substrate along the prothrombin activation pathway is supported by evidence that meizothrombin partitions among E*, E and E:Na+ forms 79, thereby casting doubts on the hypothesis that only prothrombinase assumes different conformational states 75. A realistic model of prothrombinase function should necessarily allow multiple conformational states for both enzyme and substrate.

The E*-E equilibrium has equally important implications for activated protein C. The effect of Na+ on activated protein C has been documented for a long time 58-62. Like thrombin, activated protein C is endowed with different physiological functions 80. The enzyme is a potent anticoagulant when it cleaves and inactivates factor Va with the assistance of protein S, but also acts as a potent cytoprotective agent upon interaction with and cleavage of PAR1 with the assistance of the endothelial cell protein C receptor 81-87. Earlier studies have shown that Na+ has no effect on the action of activated protein C on factor Va 60,62. Analysis of the effect of Na+ on cleavage of PAR1 reveals a slow rate in the presence of Na+ 88 but practically no activity in the absence of cation (data not shown). It is therefore possible that the role of Na+ in activated protein C is to promote the cytoprotective activity of the enzyme through the E:Na+ form. There is currently enormous interest in dissociating the anticoagulant and cytoprotective functions of activated protein C to produce variants that ameliorate inflammatory reactions without interfering with hemostasis 82,87. For this strategy to succeed, the Na+ binding affinity of activated protein C should remain unperturbed. As for factor Xa, the conformational plasticity of activated protein C becomes relevant when considering the documented multiple interactions of this enzyme 80,84,89. Existence of multiple conformations may provide an important mechanism for selecting specific functions, as demonstrated by thrombin 8,10. It is possible that different conformations of activated protein C may be involved in different physiological roles and even trigger distinct receptor signaling pathways.

The data presented in this study support the generality of the E*-E equilibrium in clotting proteases and structural studies of activated protein C and factor Xa are underway to trap these alternative conformations as done for thrombin. The E*-E equilibrium is relevant to other enzymes and has recently been invoked to explain the mechanism of K+ activation of histone deacetylase 8 90. We have proposed that the E*-E equilibrium is a basic feature of the trypsin fold and offers a simple mechanism of allosteric regulation of protease activity after the irreversible zymogen→protease conversion has taken place 91. The collapse of the 215-217 segment into the active site and/or disruption of the oxyanion hole, have been observed in the inactive form of αI-tryptase 92, the high-temperature-requirement-like protease 93, complement factor D 94, granzyme K 95, hepatocyte growth factor activator 96, prostate kallikrein 97, prostasin 98,99, complement factor B 100, the arterivirus nsp4 101, the epidermolyic toxin A 102,103 and clotting factor VIIa 49. Stabilization of E* obliterates activity of the enzyme, thereby keeping it in a zymogen-like form until binding of a suitable cofactor elicits conversion to the active form E. The new paradigm established by the E*-E equilibrium has obvious physiological relevance. In the case of complement factors, kallikreins, tryptase and some coagulation factors activity must be kept to a minimum until binding of a trigger factor ensues. Stabilization of E* may afford a resting state of the protease waiting for action, as seen for other systems 104-108. Stabilization of E* is particularly important in maintaining the resting state of complement factor D that does not have a zymogen form or known natural inhibitors 94. In this case, binding of substrate induces the transition to the active E form. Factor B is mostly inactive until binding of complement factor C3 unleashes catalytic activity at the site where amplification of C3 activation is most needed prior to formation of the memrbrane attack complex 109. Indeed, the crystal structure of factor B reveals a conformation with the oxyanion hole disrupted by a flip of the 192-193 peptide bond 100. Similar arguments apply to clotting fator VIIa that is mostly inactive until complexed with tissue factor 110. In the case of complement factor B 100, hepatocyte growth factor activator 96 or clotting factor VIIa 49, stabilization of E* is achieved after the zymogen→protease conversion has taken place and transition to the active E form relies on the binding of substrate and/or cofactors. Finally, stabilization of E* offers a rational strategy to engineering “allosteric switches” that become activated “on demand” upon binding of cofactors. A number of anticoagulant thrombin mutants have been shown to actually exploit such mechanism 26,41.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health Research Grants HL49413, HL58141 HL73813 and HL95315 (to E.D.C.)

References

- (1).Neurath H, Dixon GH. Fed Proc. 1957;16:791–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Fehlhammer H, Bode W. J Mol Biol. 1975;98:683–92. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Fehlhammer H, Bode W, Huber R. J Mol Biol. 1977;111:415–438. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(77)80062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Wang D, Bode W, Huber R. J Mol Biol. 1985;185:595–624. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Reiling KK, Krucinski J, Miercke LJ, Raymond WW, Caughey GH, Stroud RM. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2616–24. doi: 10.1021/bi020594d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Hedstrom L. Chem Rev. 2002;102:4501–24. doi: 10.1021/cr000033x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Bode W, Schwager P, Huber R. J Mol Biol. 1978;118:99–112. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90246-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Di Cera E. Mol Aspects Med. 2008;29:203–254. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Ayala YM, Cantwell AM, Rose T, Bush LA, Arosio D, Di Cera E. Proteins. 2001;45:107–16. doi: 10.1002/prot.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Dang OD, Vindigni A, Di Cera E. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:5977–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.5977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Dang QD, Guinto ER, Di Cera E. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:146–9. doi: 10.1038/nbt0297-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Myles T, Yun TH, Hall SW, Leung LL. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:25143–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Nogami K, Zhou Q, Myles T, Leung LL, Wakabayashi H, Fay PJ. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18476–18487. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412778200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Yun TH, Baglia FA, Myles T, Navaneetham D, Lopez JA, Walsh PN, Leung LL. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:48112–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306925200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Degen SJ, McDowell SA, Sparks LM, Scharrer I. Thromb Haemost. 1995;73:203–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Miyata T, Aruga R, Umeyama H, Bezeaud A, Guillin MC, Iwanaga S. Biochemistry. 1992;31:7457–62. doi: 10.1021/bi00148a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Henriksen RA, Dunham CK, Miller LD, Casey JT, Menke JB, Knupp CL, Usala SJ. Blood. 1998;91:2026–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Sun WY, Smirnow D, Jenkins ML, Degen SJ. Thromb Haemost. 2001;85:651–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Stanchev h., Philips M, Villoutreix BO, Aksglaede L, Lethagen S, Thorsen S. Thromb Haemost. 2006;95:195–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Rouy S, Vidaud D, Alessandri JL, Dautzenberg MD, Venisse L, Guillin MC, Bezeaud A. Br J Haematol. 2006;132:770–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Pineda AO, Carrell CJ, Bush LA, Prasad S, Caccia S, Chen ZW, Mathews FS, Di Cera E. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:31842–31853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401756200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Gibbs CS, Coutre SE, Tsiang M, Li WX, Jain AK, Dunn KE, Law VS, Mao CT, Matsumura SY, Mejza SJ, Paborsky LR, Leung LLK. Nature. 1995;378:413–6. doi: 10.1038/378413a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Tsiang M, Paborsky LR, Li WX, Jain AK, Mao CT, Dunn KE, Lee DW, Matsumura SY, Matteucci MD, Coutre SE, Leung LL, Gibbs CS. Biochemistry. 1996;35:16449–57. doi: 10.1021/bi9616108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Cantwell AM, Di Cera E. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39827–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000751200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Gruber A, Cantwell AM, Di Cera E, Hanson SR. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27581–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200237200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Bah A, Carrell CJ, Chen Z, Gandhi PS, Di Cera E. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:20034–20040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.012344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Bah A, Garvey LC, Ge J, Di Cera E. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:40049–40056. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608600200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Gianni S, Ivarsson Y, Bah A, Bush-Pelc LA, Di Cera E. Biophys Chem. 2007;131:111–114. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Niu W, Chen Z, Bush-Pelc LA, Bah A, Gandhi PS, Di Cera E. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:36175–36185. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.069500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Wells CM, Di Cera E. Biochemistry. 1992;31:11721–30. doi: 10.1021/bi00162a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Di Cera E, Guinto ER, Vindigni A, Dang QD, Ayala YM, Wuyi M, Tulinsky A. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22089–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.38.22089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Lai MT, Di Cera E, Shafer JA. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30275–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.48.30275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Adams TE, Li W, Huntington JA. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:1688–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03563.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Huntington JA. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7(Suppl 1):159–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03365.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Lechtenberg BC, Johnson DJ, Freund SM, Huntington JA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005255107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Kamath P, Huntington JA, Krishnaswamy S. J Biol Chem. 2010 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.154914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Carrell CJ, Bush LA, Mathews FS, Di Cera E. Biophys Chem. 2006;121:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Bush-Pelc LA, Marino F, Chen Z, Pineda AO, Mathews FS, Di Cera E. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27165–27170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703202200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Pineda AO, Savvides SN, Waksman G, Di Cera E. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40177–40180. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200465200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Pineda AO, Zhang E, Guinto ER, Savvides SN, Tulinsky A, Di Cera E. Biophys Chem. 2004;112:253–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2004.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Gandhi PS, Page MJ, Chen Z, Bush-Pelc LA, Di Cera E. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:24098–24105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.025403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Gandhi PS, Chen Z, Mathews FS, Di Cera E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:1832–1837. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710894105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Pineda AO, Chen ZW, Bah A, Garvey LC, Mathews FS, Di Cera E. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32922–32928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605530200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Johnson DJ, Adams TE, Li W, Huntington JA. Biochem J. 2005;392:21–28. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Dang QD, Di Cera E. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:10653–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Krem MM, Di Cera E. Embo J. 2001;20:3036–45. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.12.3036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Zhang E, Tulinsky A. Biophys Chem. 1997;63:185–200. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(96)02227-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Scharer K, Morgenthaler M, Paulini R, Obst-Sander U, Banner DW, Schlatter D, Benz J, Stihle M, Diederich F. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2005;44:4400–4. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Bajaj SP, Schmidt AE, Agah S, Bajaj MS, Padmanabhan K. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:24873–88. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509971200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Schmidt AE, Padmanabhan K, Underwood MC, Bode W, Mather T, Bajaj SP. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:28987–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201892200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Rezaie AR, He X. Biochemistry. 2000;39:1817–25. doi: 10.1021/bi992006a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Rezaie AR, Kittur FS. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48262–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409964200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Orthner CL, Kosow DP. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1978;185:400–6. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(78)90182-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Monnaie D, Arosio D, Griffon N, Rose T, Rezaie AR, Di Cera E. Biochemistry. 2000;39:5349–54. doi: 10.1021/bi9926781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Underwood MC, Zhong D, Mathur A, Heyduk T, Bajaj SP. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36876–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001386200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Camire RM. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:37863–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203692200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Levigne S, Thiec F, Cherel S, Irving JA, Fribourg C, Christophe OD. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:31569–31579. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704837200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).He X, Rezaie AR. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4970–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.4970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Steiner SA, Amphlett GW, Castellino FJ. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1980;94:340–7. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(80)80226-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Steiner SA, Castellino FJ. Biochemistry. 1982;21:4609–14. doi: 10.1021/bi00262a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Steiner SA, Castellino FJ. Biochemistry. 1985;24:1136–41. doi: 10.1021/bi00326a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Steiner SA, Castellino FJ. Biochemistry. 1985;24:609–17. doi: 10.1021/bi00324a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Petrovan RJ, Ruf W. Biochemistry. 2000;39:14457–63. doi: 10.1021/bi0009486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Zogg T, Brandstetter H. Structure. 2009;17:1669–1678. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Schmidt AE, Stewart JE, Mathur A, Krishnaswamy S, Bajaj SP. J Mol Biol. 2005;350:78–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.04.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Page MJ, Di Cera E. Thromb Haemost. 2006;95:920–921. doi: 10.1160/TH06-05-0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Rezaie AR, Esmon CT. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:26104–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Roberts PS, Ottenbrite RM, Fleming PB, Wigand J. Thromb Diath Haemorrh. 1974;31:309–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Leach RD, DeWind SA, Slattery CW, Herrmann EC. Thromb Res. 1991;62:635–48. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(91)90368-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Griffon N, Di Stasio E. Biophys Chem. 2001;90:89–96. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(01)00129-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Yang L, Prasad S, Di Cera E, Rezaie AR. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38519–38524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407304200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Dang QD, Di Cera E. Blood. 1997;89:2220–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Mann KG. Chest. 2003;124:4S–10S. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.3_suppl.4s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Doyle MF, Mann KG. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:10693–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Kim PY, Nesheim ME. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:32568–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701781200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Bianchini EP, Orcutt SJ, Panizzi P, Bock PE, Krishnaswamy S. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10099–104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504704102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Orcutt SJ, Krishnaswamy S. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:54927–54936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410866200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Lee CJ, Wu S, Eun C, Pedersen LG. Biophys Chem. 2010;149:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Papaconstantinou ME, Gandhi PS, Chen Z, Bah A, Di Cera E. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:3688–3697. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8502-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Griffin JH, Zlokovic B, Fernandez JA. Semin Hematol. 2002;39:197–205. doi: 10.1053/shem.2002.34093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Bae JS, Yang L, Rezaie AR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2867–2872. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611493104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (82).Kerschen EJ, Fernandez JA, Cooley BC, Yang XV, Sood R, Mosnier LO, Castellino FJ, Mackman N, Griffin JH, Weiler H. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2439–48. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (83).Mosnier LO, Zampolli A, Kerschen EJ, Schuepbach RA, Banerjee Y, Fernandez JA, Yang XV, Riewald M, Weiler H, Ruggeri ZM, Griffin JH. Blood. 2009;113:5970–5978. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-183327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (84).Riewald M, Petrovan RJ, Donner A, Mueller BM, Ruf W. Science. 2002;296:1880–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1071699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (85).Yang L, Bae JS, Manithody C, Rezaie AR. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25493–500. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702131200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (86).Feistritzer C, Schuepbach RA, Mosnier LO, Bush LA, Di Cera E, Griffin JH, Riewald M. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:20077–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600506200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (87).Mosnier LO, Yang XV, Griffin JH. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:33022–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (88).Di Cera E. Blood. 2009;113:5699–5700. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-211292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (89).Yang XV, Banerjee Y, Fernandez JA, Deguchi H, Xu X, Mosnier LO, Urbanus RT, de Groot PG, White-Adams TC, McCarty OJ, Griffin JH. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:274–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807594106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (90).Gantt SL, Joseph CG, Fierke CA. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:6036–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.033399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (91).Di Cera E. IUBMB Life. 2009;61:510–515. doi: 10.1002/iub.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (92).Rohr KB, Selwood T, Marquardt U, Huber R, Schechter NM, Bode W, Than ME. J Mol Biol. 2006;357:195–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (93).Krojer T, Garrido-Franco M, Huber R, Ehrmann M, Clausen T. Nature. 2002;416:455–9. doi: 10.1038/416455a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (94).Jing H, Babu YS, Moore D, Kilpatrick JM, Liu XY, Volanakis JE, Narayana SV. J Mol Biol. 1998;282:1061–81. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (95).Hink-Schauer C, Estebanez-Perpina E, Wilharm E, Fuentes-Prior P, Klinkert W, Bode W, Jenne DE. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50923–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207962200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (96).Shia S, Stamos J, Kirchhofer D, Fan B, Wu J, Corpuz RT, Santell L, Lazarus RA, Eigenbrot C. J Mol Biol. 2005;346:1335–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (97).Carvalho AL, Sanz L, Barettino D, Romero A, Calvete JJ, Romao MJ. J Mol Biol. 2002;322:325–37. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00705-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (98).Rickert KW, Kelley P, Byrne NJ, Diehl RE, Hall DL, Montalvo AM, Reid JC, Shipman JM, Thomas BW, Munshi SK, Darke PL, Su HP. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:34864–34872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805262200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (99).Spraggon G, Hornsby M, Shipway A, Tully DC, Bursulaya B, Danahay H, Harris JL, Lesley SA. Protein Sci. 2009;18:1081–94. doi: 10.1002/pro.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (100).Ponnuraj K, Xu Y, Macon K, Moore D, Volanakis JE, Narayana SV. Mol Cell. 2004;14:17–28. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00160-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (101).Barrette-Ng IH, Ng KK, Mark BL, Van Aken D, Cherney MM, Garen C, Kolodenko Y, Gorbalenya AE, Snijder EJ, James MN. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:39960–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206978200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (102).Cavarelli J, Prevost G, Bourguet W, Moulinier L, Chevrier B, Delagoutte B, Bilwes A, Mourey L, Rifai S, Piemont Y, Moras D. Structure. 1997;5:813–24. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00235-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (103).Vath GM, Earhart CA, Rago JV, Kim MH, Bohach GA, Schlievert PM, Ohlendorf DH. Biochemistry. 1997;36:1559–66. doi: 10.1021/bi962614f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (104).Eisenmesser EZ, Bosco DA, Akke M, Kern D. Science. 2002;295:1520–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1066176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (105).Lu HP, Xun L, Xie XS. Science. 1998;282:1877–82. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (106).Sytina OA, Heyes DJ, Hunter CN, Alexandre MT, van Stokkum IH, van Grondelle R, Groot ML. Nature. 2008;456:1001–4. doi: 10.1038/nature07354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (107).Erlandson KJ, Miller SB, Nam Y, Osborne AR, Zimmer J, Rapoport TA. Nature. 2008;455:984–7. doi: 10.1038/nature07439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (108).Zimmer J, Nam Y, Rapoport TA. Nature. 2008;455:936–43. doi: 10.1038/nature07335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (109).Gros P, Milder FJ, Janssen BJ. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:48–58. doi: 10.1038/nri2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (110).Banner DW. Thromb Haemost. 1997;78:512–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]