Abstract

Loss of postural stability, as exacerbated by chronic bed rest, aging, neuromuscular injury or disease, results in a marked increase in the risk of falls, potentiating severe injury and even death. To investigate the capacity of low magnitude mechanical signals (LMMS) to retain postural stability under conditions conducive to its decline, twenty-nine healthy adult subjects underwent 90 days of 6-degree head down tilt bed-rest. Treated subjects underwent a daily 10 minute regimen of 30 Hz LMMS at either a 0.3g-force (n=12) or 0.5g force (n=5). Control subjects (n=13) received no LMMS treatment. Postural stability, quantified by dispersions of the plantar-based center of pressure, deteriorated significantly from baseline in control subjects, with displacement and velocity at 60d increasing 98.7% and 193% respectively, while the LMMS group increased only 26.7% and 6.4%, reflecting a 73% and 97% relative retention in stability as compared to control. Increasing LMMS magnitude from 0.3 to 0.5g had no significant influence on outcomes. LMMS failed to spare loss of muscle extension strength, but helped to retain flexion strength (e.g., 46.2% improved retention of baseline concentric flexion strength vs. untreated controls; p=0.01). These data suggest the potential of extremely small mechanical signals as a non-invasive means of preserving postural control under the challenge of chronic bed rest, and may ultimately represent non-pharmacologic means of reducing the risk of debilitating falls in elderly and infirm.

Keywords: fracture, falls, aging, disuse, bed rest

Introduction

Aging, chronic bed rest, and long term spaceflight, distinct at one level, are similar in that they contribute to the progressive decline of the musculoskeletal system as indicated by the loss of bone density, muscle mass, and postural stability.(1,2) In parallel, neuromuscular disease and/or poor acclimation of the central nervous system to these debilitating conditions leads to a reduced ability to control posture and further increase the risk of falls.(3,4) Postural instability, combined with a compromised integrity of the skeletal system in the elderly and infirm,(5) conspire towards a marked increase in injury, and even death due to falls.(6)

Improved understanding of the loss of postural control under conditions such as extended bed rest, as well as identifying means of slowing this decline, may lead to strategies of preserving quality of life for a range of individuals.(7) In addition to the loss of muscle mass and strength,(8) it has been hypothesized that an impairment of central processing and neural pathways for motor control contributes to a reduction in the ability to control postural stability.(9) Retaining postural control is also critical for astronaut safety,(10) as plans for an extended human presence in space, including a manned mission to Mars, necessitate a safe and effective countermeasure to preserve musculoskeletal health in the absence of gravity. As a means of evaluating the physiologic complications of spaceflight on the human body, long term confined bed rest has become accepted as an appropriate, ground-based analog for microgravity.(2)

Several biomechanical-based assays have been used to assess fall-risk, including the recording of the ground reaction vector during upright stance, known as center of pressure (COP). The resulting anterior-posterior (AP), medial-lateral (ML) and combined resultant (R) directions can be analyzed to calculate COP deviation magnitude, peak and average COP velocities, and root-mean-square amplitude, all of which have been used as predictors of fall-risk.(11,12)

With age as with extended disuse, there is a gradual decrease in stable upright posture and an increased incidence of falls which parallels the weakening of the skeleton and thus an aggregate increase in the risk of bone fracture.(13) Towards the other side of the activity spectrum, exercise regimes increase muscle strength across several age groups and in selected populations, strenuous load-bearing challenges increase bone density.(14) Distilling exercise to mechanical signals, high intensity whole body vibration, with accelerations which exceed 10g’s (where 1.0g is Earth’s gravitational field, or 9.8m/s2), has been shown to provide acute improvements in muscle strength, but risk of a range of musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, vestibular and cognitive injuries are elevated due to the severity of the percussive impacts.(15)

In contrast to a “bigger is better” strategy, low magnitude mechanical signals (LMMS), below 1g, have been demonstrated as anabolic to both bone (16–18) and muscle,(19) perhaps by biasing the differentiation pathway of mesenchymal stem cells towards osteoblastogenesis and away from adipogenesis.(20) As modeled by tail-suspension in rodents, brief daily exposure of LMMS inhibited disuse induced bone loss whereas a similar period of weight bearing failed to curb this osteopenia.(21) Because of the animal and human evidence of LMMS influence at several levels in the musculoskeletal system, we hypothesized herein that brief daily exposure to LMMS may slow the loss of postural stability which typically parallels extended bed-rest.

Methods

Subjects

The experimental design and all procedures were reviewed and approved by the Committee on Research in Human Subjects (CORIHS) of Stony Brook University, the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB), and NASA’s Johnson Space Center. Healthy adults from 25 to 55 years of both genders and all racial groups were considered from the Houston area, recruited via print and radio ads. Written informed consent was collected from all subjects prior to their entry into the study. By NASA regulations, all subjects were paid a stipend for their participation.

Thirty-six subjects successfully enrolled in the protocol, while a total of 30 subjects completed 90d of bed rest, including 13 controls and 17 LMMS. The first four enrollees were assigned to the control group, while all remaining subjects were randomly assigned to control or LMMS groups. To assure no bias in selection, assignment was performed by a non-affiliated researcher. The protocol was abandoned for four subjects at 45d, as the UTMB hospital was evacuated prior to the arrival of Hurricane Rita. Of the 32 subjects that completed the protocol, data from two subjects (one from each group) were omitted due to technical failure of the hardware collection system. No significant differences in body habitus were found between the control (8 male, 5 female, age 34.7 ± 7.9, weight 73.0 ± 17.1 kg, height 170.1 ± 11.4 mm) and LMMS groups (11 male, 6 female, age 35.6 ± 7.1, weight 74.4 ± 8.7 kg, height 163.9 ± 19.2 mm). At the conclusion of bed rest, all subjects were provided with 2 weeks of rehabilitation.

Study Protocol

Subjects entered the UTMB hospital 14 days prior to bed rest, during which baseline data was collected. During this time, a strict 16-hour wake, 8-hour sleep schedule was enforced and maintained throughout the study. From the initiation of bed rest, beds were set to a 6 degree head-down tilt. Through the entire bed rest period of 90 days, subjects were supine (except for one brief stability measure at 60d, see below), and all daily functions were performed while maintaining head-down tilt. Daily stretches and odd-day massages were used to reduce soreness. Subjects were monitored by closed circuit cameras to ensure compliance. The first four subjects were assigned to the control group, after which subjects were randomly assigned to either control or treatment groups.

LMMS Intervention

Subjects in the treatment group received 10 minutes of daily LMMS while confined to the supine position. LMMS was delivered via a foot-based vibration platform, which provided a 30 Hz sinusoidal vibration at either 0.30 ± 0.02g (13 subjects) or 0.50 ± 0.04g (5 subjects) peak-to-peak (Marodyne Medical, Lakeland, FL, USA). The fidelity of the sinusoidal signal was controlled through closed-loop feedback from an accelerometer mounted on the top platen of the device. The displacement of the plate was under 140 microns, with exposure to vibration of such a frequency/amplitude profile considered safe by International Safety Organization (ISO-2631) for as much as four hours each day.(22)

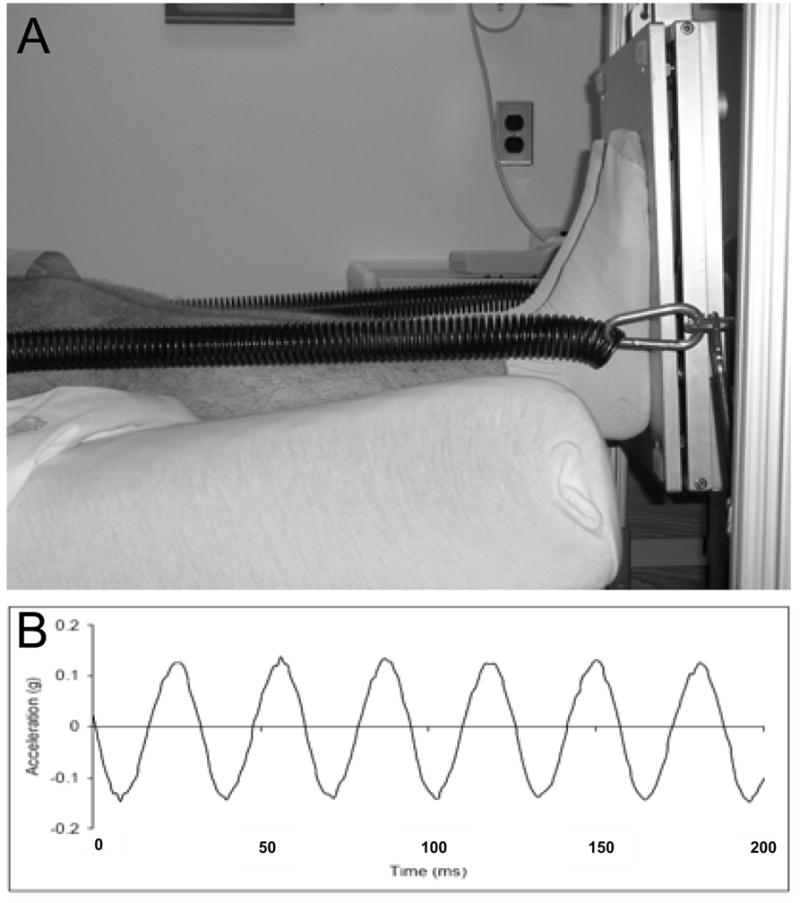

While confined to the head-down tilt position, subjects donned a vest coupled to the platform by linear springs (Figure 1a). Spring tension was calibrated to provide 60% of pre-bed rest body weight during relaxed upright stance. Subjects were weighed daily, and the loading was verified at 30 day intervals. Daily during bed rest, the subject placed their feet on the proximal surface of the LMMS device and extended their legs to stretch the springs and provide a resistive force. The LMMS device was then activated, delivering the mechanical signal (Figure 1b). Slight shifting of weight during treatment was compensated by the closed-loop feedback control. Due to the inclusion of control subjects for other NASA bed rest protocols, control subjects in this study did not use the LMMS harness nor were subject to a daily 60% static load.

Figure 1.

Figure 1a. Setup showing LMMS treatment. Coupling spring attached to bottom surface of vibration platform provides a load of 60% of the subjects’ pre-bed rest body weight via a shoulder harness. The subject pushes on the plate with straight legs, in a “relaxed stance,” for 10 minutes while the platform provides a 30 Hz, 0.3g sinusoidal acceleration along the their load bearing axis.

Figure 1b. Surface acceleration of the top platen of the vibration device during subject treatment with 60% body weight, showing 0.3g peak to peak acceleration. A closed loop feedback control system built into the platform uses a build in accelerometer to automatically adjust the electrical drive signal to the actuator to provide a consistent, high-fidelity sinusoidal acceleration/deceleration for subject of various heights and weights.

Postural Stability

Baseline, 60d and 90d postural stability measures were collected in a non-blinded fashion by the same person who supervised the daily application of the LMMS intervention. All data analysis was automated by custom software, thus minimizing the potential for bias by the operator. COP measurements were performed using a force plate (Kistler 9286AA, Winterthur, Switzerland) with an eight-channel amplifier, an analog-digital converter, and Bioware 3.2.6.104 software. Data was over-sampled at 1000 Hz, then low-pass filtered (2nd order Butterworth, 50 Hz cutoff), and stored on a laptop for later analysis. The force plate’s load cells were tested for accuracy and precision before each data collection by applying forces to the plate along each edge and each corner.

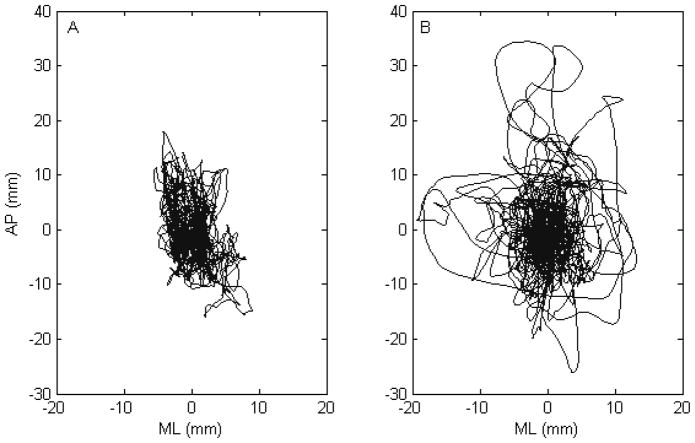

During postural stability testing, subjects were instructed to stand upright in relaxed stance and with feet planted at shoulder width and with hands at sides in quiet stance. COP was recorded for 4 minutes (Figure 2) under eyes opened and closed conditions, a 1 inch diameter blue marker at eye level on a blank white wall 2 meters from the subject to providing a visual reference point, with a 5 minute seated break between trials.

Figure 2.

Stabilogram of a typical subject at baseline (A) and after bed rest (B), with anterior-posterior and medio-lateral COP displacement expressed in mm. At baseline, the subject’s COP remains near the center of the plate, with occasional perturbations away from the stable region, which become exaggerated after chronic bed rest.

Postural stability analysis was performed using a custom MATLAB program (v.7.0.1, The MathWorks, Natick, Massachusetts). Traditional scalar parameters of COP displacement and velocity were calculated, and power spectral density analysis was performed using the Fast Fourier Transform. Stabilogram Diffusion Analysis was performed using the methods described in Collins et al.(23)

Neurosensitivity

At baseline and day 90, a two-point discrimination test was performed on the first and fifth toe, the first and fifth metatarsal head, and the heel.(24) A mono-filament sensitivity test was performed on the first and fifth toe, first and fifth metatarsal head, heel, and ankle.(25)

Muscle Strength

At baseline and day 90, subjects performed maximal effort contractions of the back and lower limbs on an isokinetic dynamometer. Maximum concentric and eccentric contractions in extension and flexion were performed at the knee, ankle, and back. Knee contractions were performed at 60° and 180° per second, ankle contractions were performed at 30° per second, and back contractions were performed at 60° per second.

Statistics

Student t-tests were used for BMD and Muscle measures, while Kruskal-Wallis tests were performed on the postural control data with a Mann-Whitney U post-hoc with Bonferroni correction. Statistical tests were performed using SPSS (version 14.0.0, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Postural Control

Following bed-rest, no effect was demonstrated to compromise any measure of neurosensitivity of the foot, with average two-point discrimination score of 11.2 ± 3.3mm and 11.1 ± 2.2 at baseline and 10.3 ± 3.3 and 11.0 ± 2.2 post-bed rest in control and LMMS groups respectively. No difference was found in postural control measures between groups at baseline. When comparing the 0.3g to the 0.5g LMMS groups, no differences in any parameter were identified at any time-point, and thus these groups were pooled and compared against controls.

Relative to baseline, displacement (Table 1) and velocity (Table 2) following bed rest increased significantly in the control group. With eyes closed, compared to baseline, there was a significant increase in each stability parameter after both 60 and 90 days, and while there was a minor improvement between day 60 and 90, this change was non-significant. A similar, but diminished, loss of stability was measured in the eyes open condition.

Table 1.

Mean values ± S.D of COP Displacement Magnitude, measured with eyes opened (O) and closed (C). No difference was observed at baseline in any COP Displacement parameter, though significant differences were measured, relative to baseline, between both control and LMMS groups at day 60 and 90. For the AP directions in the eyes-closed condition, the percent difference from baseline for both control and LMMS, as well as the “benefit” of LMMS (inferred from relative LMMS retention of baseline measures as compared to control) at that time point, are also provided.

| Eyes | Baseline | Day 60 | Day 90 | p value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | LMMS | Control | LMMS | Control | LMMS | Day 60 | Day 90 | ||

| Peak COP Displacement (AP) (mm) | O C |

12.9 ± 3.9 15.2 ± 3.6 |

13.8 ± 4.7 15.0 ± 5.4 |

17.8 ± 4.2 30.2 ±13.8 |

17.9 ± 6.4 19.0 ± 4.8 |

16.9 ± 4.9 24.8 ± 9.0 |

18.8 ± 9.8 21.0 ± 7.8 |

0.38 0.04 |

0.49 0.14 |

| Change From Baseline | C | +98.7% P = 0.03 |

+26.7% P = 0.09 |

+63.2% P = 0.005 |

+40.0% P = 0.02 |

||||

| Benefit of LMMS | C | +73% P = 0.09 |

+37% P = 0.26 |

||||||

| Peak COP Displacement (ML) (mm) | O C |

5.7 ± 2.5 7.6 ± 4.5 |

6.7 ± 5.5 7.1 ± 5.2 |

11.6 ± 5.0 18.4 ± 12.2 |

9.6 ± 5.5 10.4 ± 2.9 |

11.2 ± 4.1 14.9 ± 6.4 |

11.1 ± 6.3 11.9 ± 6.4 |

0.46 0.05 |

0.29 0.14 |

| RMS Displacement (AP) | O C |

3.9 ± 1.0 4.1 ± 0.9 |

4.5 ± 1.5 4.1 ± 1.5 |

4.5 ± 1.4 7.2 ± 2.8 |

4.6 ± 1.3 5.1 ± 1.1 |

4.9 ± 1.2 6.3 ± 2.3 |

5.1 ± 2.4 5.3 ± 1.7 |

0.21 0.07 |

0.15 0.05 |

| Change From Baseline | C | +75.6% P = 0.008 |

+24.4% P = 0.14 |

+53.7% P = 0.005 |

+29.3% P = 0.02 |

||||

| Benefit of LMMS | C | +67% P = 0.07 |

+45% P = 0.19 |

||||||

| RMS COP Displacement (ML) | O C |

1.6 ± 0.8 1.9 ± 1.0 |

1.8 ± 1.1 1.7 ±1.0 |

3.0 ± 1.0 4.1 ± 2.1 |

2.4 ± 0.9 2.8 ± 0.8 |

2.9 ± 1.2 3.4 ± 1.1 |

2.7 ± 1.5 3.0 ± 1.3 |

0.15 0.07 |

0.07 0.13 |

AP = antero-posterior, ML = medio-lateral.

Table 2.

Mean values ± S.D of COP Displacement Velocity postural stability parameters with eyes opened (O) and closed (C). No difference was observed at baseline in any COP Velocity parameter, though significant differences were measured, relative to baseline, between both control and LMMS groups at day 60 and 90. For the AP directions in the eyes-closed condition, the percent difference from baseline for both control and LMMS, as well as the “benefit” of LMMS (inferred from relative LMMS retention of baseline measures as compared to control) at that time point, are also provided.

| Eyes | Baseline | Day 60 | Day 90 | p value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | LMMS | Control | LMMS | Control | LMMS | Day 60 | Day 90 | ||

| Peak Velocity (AP) (mm/s) | O C |

38.0 ±18.2 51.5 ± 19.0 |

41.7 ± 17.4 68.3 ± 45.7 |

100.2 ± 69.9 150.7 ±102.1 |

57.4 ± 18.7 72.7 ± 12.0 |

62.7 ± 13.0 115.9 ± 11.1 |

34.7 ± 22.2 82.2 ± 26.5 |

0.04 0.004 |

0.49 0.09 |

| Change From Baseline | C | +192.6% P = 0.008 |

+6.4% P = 0.43 |

+125.0% P = 0.002 |

+20.4% P = 0.14 |

||||

| Benefit of LMMS | C | +97% P = 0.02 |

+83% P = 0.01 |

||||||

| RMS Velocity (AP) | O C |

6.9 ± 2.5 10.0 ± 3.4 |

8.1 ± 3.5 11.2 ± 5.8 |

14.8 ± 9.2 26.6 ± 20.7 |

10.0 ± 2.2 14.3 ± 2.7 |

10.8 ± 2.5 19.5 ± 11.1 |

12.1 ± 4.0 16.1 ± 5.3 |

0.11 0.02 |

0.21 0.23 |

| Change From Baseline | C | +166.6% P = 0.008 |

+27.7% P = 0.041 |

+95.0% P = 0.002 |

+43.8% P = 0.006 |

||||

| Benefit of LMMS | C | +83% P = 0.05 |

+54% P = 0.06 |

||||||

| Mean Velocity (mm/s) | O C |

6.3 ± 2.1 8.7 ± 2.8 |

7,1 ± 3.1 9.6 ± 4.8 |

13.5 ± 8.8 23.9 ± 20.1 |

9.1 ± 2.0 12.2 ± 2.3 |

10.0 ± 2.3 16.8 ± 8.5 |

11.0 ± 4.3 14.3 ± 5.4 |

0.10 0.02 |

0.38 0.18 |

AP = antero-posterior, ML = medio-lateral

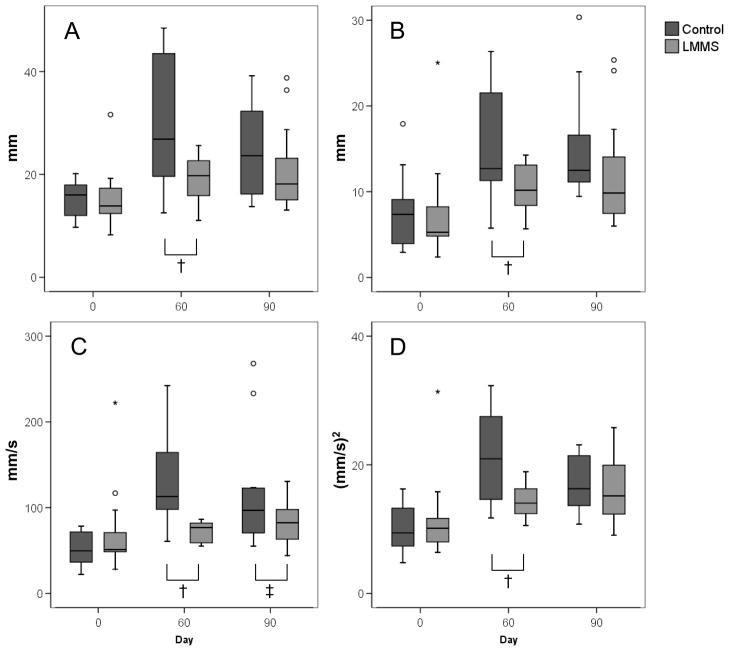

In contrast, each stability parameter measured in the LMMS was markedly closer to baseline measures. Like the controls, increases in the LMMS group were significant relative to baseline after both 60 and 90 days of bed rest, with the exception of AP velocity which did not change from baseline (Figure 3). For example, with eyes closed, there was an increase of 99.1% and 63.4% in peak AP displacement in the control group after 60 and 90d of bed rest, respectively, as compared to a 27.0% and 40.3% increase in the LMMS group (Table 1). In AP velocity, there was a 192.7% and 125.1% increase in the controls at days 60 and 90, as compared to a 6.4% and 20.3% increase in the LMMS group (Table 2). Thus, at day 60 for example, the LMMS intervention resulted in a 73% (p=0.036) improvement in peak AP displacement, and 97% (p<0.004) improvement in peak AP velocity, as compared to untreated controls.

Figure 3.

As compared to baseline, control subjects (n = 13) realized a large increase in peak AP (A) and ML (B) COP displacement and velocity (C) as well as root-mean-square (D) of velocity. During upright stance after bed rest, subjects were unable to maintain a constant upright stance and experience COP dispersions at higher magnitudes and velocities, as shown in AP Velocity, and in variability, as seen in the AP RMS Velocity. In contrast, LMMS subjects (n = 17), in both the eyes closed and open conditions (light gray), showed significantly improved retention of baseline postural control measures. † p<0.05, ‡ p<0.1, ° indicates outliers from the box-plot. Eyes closed data shown.

For both controls and LMMS subjects, the overall loss of postural control was reduced when stability tests were performed with eyes opened as compared to eyes closed. The only significant difference between the control and LMMS groups when eyes were opened was peak COP velocity (p=0.016).

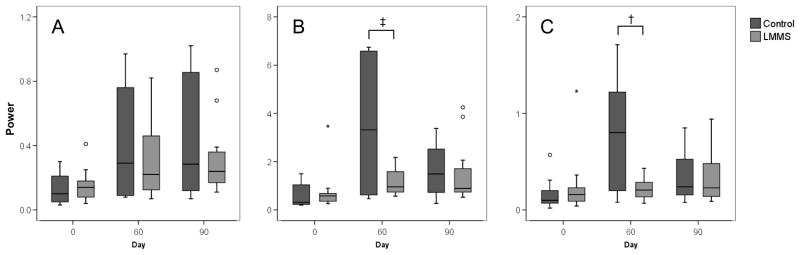

Power Spectrum of COP

Increases in frequency power of stance were observed in both groups following bed rest. No change was seen after bed rest with respect to median frequency. Compared to LMMS, control subjects had a large increase in both mid (p=0.035) and high (p=0.002) frequency ranges with eyes closed. Control subjects experienced a 313% and 287% increase in mid-frequency energy at 60 and 90 days, respectively, and a 615% and 293% increase in high-frequency energy. This was significantly higher than that measured in the LMMS subjects, with a 125% and 147% increase in the mid-frequency at day 60 and 90, and 62% and 103% increase at the high- frequency (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Frequency analysis of stabilogram showing frequency changes in AP shear forces during quiet stance in (A) low, (B) mid, and (C) high frequency ranges. Control subjects displayed an increase in frequency in all three frequency groups. The LMMS subjects showed the greatest increase relative to baseline in low frequency and the smallest in high frequency; however these changes were not significant. The LMMS subjects showed significantly better retention of baseline mid and high frequencies as compared to the control group. † p<0.05 ‡ p<0.1, ° indicates outliers from the box-plot. Eyes closed data shown.

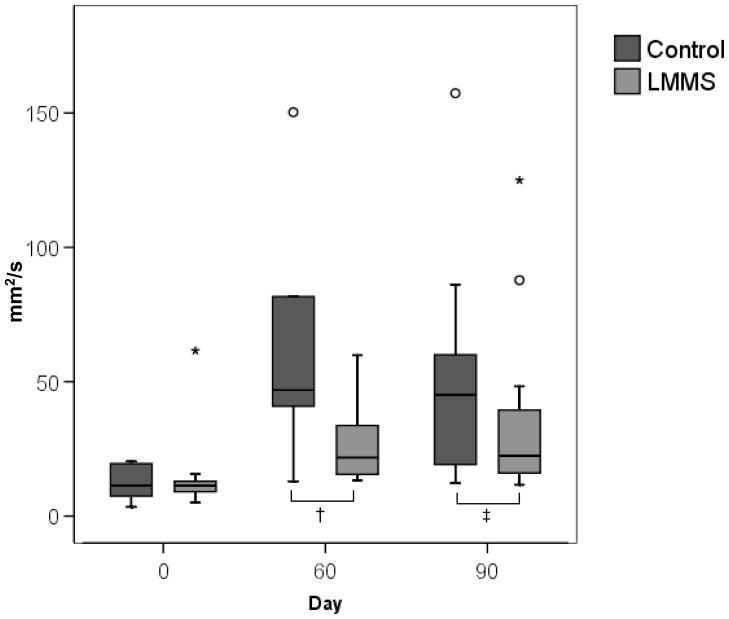

Stabilogram Diffusion Analysis

With eyes closed, the short-term diffusion coefficient experienced an increase in both the control and LMMS groups. However, this increase was significantly lower in the LMMS subjects (p=0.036; Figure 5). There was no difference between groups with eyes opened. No other differences were found between groups though SDA analysis.

Figure 5.

An increase in stabilogram diffusion analysis parameters occurred after 90 days of bed rest, further indicating the deterioration of postural control. The increase in short term coefficient represents a decrease in stability in short time intervals during quiet stance. When the postural control system is compromised, the open loop control system becomes more unstable, and a higher degree of displacement occurs before the body switches to a closed loop system to maintain upright stance. The LMMS subjects showed significantly better retention of baseline measures as compared to the control group. † p<0.05 ‡ p<0.1, ° indicates outliers from the box-plot. Eyes closed data shown.

Muscle Strength

Over the 90d protocol, ankle, knee, and back strength, as well as knee endurance, decreased between 10.2 and 20.0% in the control group, and between 2.4 and 14.2% in the LMMS group (Table 3). In the LMMS group, knee concentric flexion strength (46.2% improved retention of baseline measures vs. control; p=0.01) and concentric endurance (79.8% improved retention vs. control; p=0.02) at 180°/sec were retained significantly better than controls relative to baseline measures. In the LMMS subjects, knee concentric flexion strength at 60°/sec (21.9% improved retention of baseline measures vs. control; p=0.13), ankle eccentric flexion strength at 30°/sec (37.3% improved retention of baseline measures vs. control; p=0.07), and back concentric flexion strength at 60° (54.2% improved retention of baseline measures vs. control; p = 0.10) each showed a trend towards improved retention of baseline measures relative to control.

Table 3.

Indices of MUSCLE STRENGTH measured before and after bed rest in controls and LMMS. Baseline and day 90 values are presented in foot-pounds. LMMS did not show a significant “benefit” on preserving muscle extension in concentric or eccentric motion; however there was a significant retention during flexion in multiple concentric measures. Percent difference from baseline for both control and LMMS, as well as the “benefit” of LMMS (inferred from relative LMMS retention of baseline measures as compared to control) at that time point, are also provided.

| Control Baseline | LMMS Baseline | Control 90d | LMMS 90d | Benefit of LMMS | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knee Concentric Strength | ||||||

| Extension at 60°/sec | 109 ± 43 | 120 ± 31 | 81 ± 39 | 90 ± 24 | +2.7% | 0.33 |

| Extension at 180°/sec | 80 ± 33 | 88 ± 28 | 63 ± 28 | 70 ± 23 | +3.7% | 0.48 |

| Flexion at 60°/sec | 64 ± 25 | 63 ± 17 | 51 ± 19 | 53 ± 14 | +21.9% | 0.13 |

| Flexion at 180°/sec | 48 ± 19 | 51 ± 15 | 41 ± 16 | 47 ± 13 | +46.2% | 0.01 |

| Knee Concentric Endurance | ||||||

| Extension at 180°/sec | 1158 ± 511 | 1028 ± 339 | 945 ± 442 | 881 ± 296 | +22.3% | 0.17 |

| Flexion at 180°/sec | 624 ± 306 | 510 ± 130 | 521 ± 279 | 493 ± 171 | +79.8% | 0.02 |

| Ankle Concentric Strength | ||||||

| Extension at 30°/sec | 72.5 ± 22·8 | 80.4 ± 16.5 | 52.9 ± 23.7 | 59 ± 16 | +1.5% | 0.32 |

| Flexion at 30°/sec | 22.1 ± 8·8 | 24.0 ± 6.6 | 20.5 ± 8.3 | 21.8 ± 6.5 | −26.6% | 0.28 |

| Ankle Eccentric Strength | ||||||

| Extension at 30°/sec | 108 ± 28.0 | 121 ± 29.5 | 74.8 ± 34.1 | 83.2 ± 25.3 | −1.6% | 0.39 |

| Flexion at 30°/sec | 36 ± 12.4 | 38.9 ± 10.2 | 30.1 ± 13.3 | 34.9 ± 8.8 | +37.3% | 0.07 |

| Back Concentric Strength | ||||||

| Extension at 60°/sec | 249 ± 97 | 222 ± 72 | 218 ± 96 | 202 ± 72 | +27.6% | 0.44 |

| Flexion at 60°/sec | 132 ± 23 | 133 ± 46 | 119 ± 31 | 127 ± 44 | +54.2% | 0.10 |

P-values represent the significance of the effects of LMMS vs. controls.

Discussion

Confined, chronic bed rest through a period of ninety days caused a marked decline in a range of postural control elements. It is important to note that a slight, non-significant trend towards recovery of these measures occurred between days 60 and 90, suggesting that a maximal deterioration in COP measures had been reached as early as two months. Chronic bed rest also resulted in decrements to muscle strength and endurance, thus biasing several critical control systems towards instability and falling. This decline stability and strength was significantly attenuated by brief daily exposure to extremely low magnitude mechanical signals, delivered to plantar surface of the foot of the supine subject. Increasing the acceleration from 0.3g to 0.5g failed to further influence postural stability measures, suggesting that the magnitude of the signal was not central to the responsiveness of the “system,” and instead a dynamic component of the stimulus, such as frequency, was the critical element, perhaps providing a surrogate for the mechanical information provided by the contractile spectra of muscle activity.(18)

With eyes closed, the subjects’ ability to maintain stable upright posture was severely compromised. Interestingly, the eyes-opened condition reduced this instability, indicating the importance of visual cues in retaining balance even under pathologic conditions. With eyes closed, the control group had nearly a doubling of COP displacement and tripling of COP velocity after 60 days of bed rest, with similar increases in RMS. In contrast, LMMS alleviated these losses, with treated subjects showing only 27% increase in COP displacement, and 6% increase in COP velocity over the same time period, reflecting a significant “improvement” in retention of baseline measures. It seems unlikely that the relative retention of postural control measured in LMMS subjects could have been achieved solely by a 20% difference in muscle flexion strength. Further, while no changes where detected in the neurosensitivity of the feet, unmeasured changes in proprioception of the knee, ankle, and torso could play an important role in maintaining stable posture. The contribution of visual cues to balance supports the conclusion that no factor alone can be held responsible for the loss of stability. Other parameters, unmeasured in this study (e.g., mechanical retention of neural control), may have contributed to the stability outcomes. Instead, we interpret these data to indicate that the LMMS, rather than working through a single sensory or strength mechanism, helps to retain stability by subtly influencing a multitude of neuromuscular control elements, which in aggregate work towards retaining balance and postural control. While difficult to demonstrate in a relatively small clinical trial, such parameters might also include the stimulation/retention of the interconnectivity and communication of connective tissue cell populations,(26) and even the regenerative/repair viability, activity and capacity of the neural or mesenchymal stem cell population.(20,27)

Muscle extension strength, which declined as a consequence of bed rest, was not preserved by LMMS. However, when compared to the loss measured in controls, concentric muscle flexion strength in the knee and ankle responded with significantly improved retention in the LMMS group, reinforcing both animal (28) and clinical (18) studies which indicate an anabolic response in muscle to LMMS. To a certain degree, the mitigation of postural stability loss could be due in part to the relative improvement in flexural strength compared to controls, but some benefit of the mechanical intervention may also have been realized through an aggregate of subtle benefits to muscle control, blood-flow, and/or vestibular function. Of course, further studies would be needed to verify this conjecture.

While not having a sham control is a limitation of this bed rest study, the impact of its absence is somewhat diminished by the extensive data from NASA spaceflight protocols which show that dynamic and/or static load bearing through a shoulder or belt-based harness system, inducing as much as 100% body weight, failed to suppress de-conditioning of the musculoskeletal system.(29) Additionally, short duration bed rest interrupted by daily exercise, with and without harness systems, has failed to preserve postural stability, providing further evidence that a static challenge of weight bearing as provided by the 60% body weight harness system would have had minimal effect on the muscle and stability parameters measured here. For example, bed rest interrupted by twice daily leg exercise in partially upright position showed retention of muscle strength, but had no effect in retaining postural control.(30) Ninety minutes of a combined isotonic and isokinetic leg exercise, induced by a harness system, also failed to mitigate the losses of postural control that parallels this bed rest model of spaceflight.(31) Other limitations of our study include the relatively small sample size, and the wide range of participants, the diversity of which was designed to reflect the range of the recruitment age/habitus for the astronaut corps.

In summary, chronic bed rest severely decayed several critical indices of postural control. This degree of deterioration in postural stability was significantly alleviated by brief, daily treatment of LMMS delivered through a low intensity (<1g) vibrating platform. We interpret this retention of stability and postural control to indicate that these mechanical signals serve, to an extent, as a surrogate for key regulatory signals which normally arise from the dynamics of normal weight bearing, including the direct mechanical stimulation of musculoskeletal precursors.(20,27) Importantly, these results emphasize that mechanical signals need not be endured for long periods of time nor reach great magnitudes to be beneficial. Further research is needed to determine if this mechanical regimen is effective in restoring postural control in those already at risk, such as the elderly or infirm. Together, these data indicate suggest that low magnitude mechanical signals can help preserve balance and postural stability in circumstances where normal weight bearing challenge to the musculoskeletal system are not otherwise possible, as might arise with aging, chronic illness, extended bed-rest or even space-flight.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the subjects who volunteered for this study, as well as the entire clinical and support staff of the NASA Long-Term Bed-Rest Unit at the University of Texas Medical Branch. We are also grateful for the financial support from NASA, through grant NNJ04HI06G, and the NASA Flight Analogs/Bed Rest Research Project. The work was also supported in part by grant M01 RR-00073 from the National Center for Research Resources of the National Institutes of Health. Finally, we would like to thank Dr. Jan Meck and the JSC-Flight Analog unit at the UTMB, for their invaluable help in running this study, and providing access to a tremendous research resource.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

CTR is a co-founder of Marodyne Medical, Inc. This potential conflict of interest was disclosed to the Internal Review Board of Johnson Space Center, the University of Texas Medical Branch, and Stony Brook University, and was included in the Informed Consent provided to each subject considering entering the trial. To minimize any potential conflict, the trial was designed such that CTR had no interaction with the subjects during recruitment, preadmission evaluation, bed-rest or recovery. No other authors have any conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Jesse Muir, Email: jmuir@ic.sunysb.edu.

Stefan Judex, Email: Stefan.Judex@sunysb.edu.

Yi-Xian Qin, Email: Yi-Xian.Qin@sunysb.edu.

Clinton Rubin, Email: clinton.rubin@sunysb.edu.

References

- 1.Leblanc AD, Schneider VS, Evans HJ, Engelbretson DA, Krebs JM. Bone mineral loss and recovery after 17 weeks of bed rest. J Bone Miner Res. 1990;5(8):843–50. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650050807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.LeBlanc A, Rowe R, Evans H, West S, Shackelford L, Schneider V. Muscle atrophy during long duration bed rest. Int J Sports Med. 1997;18 (Suppl 4):S283–5. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-972726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lord SR, Tiedemann A, Chapman K, Munro B, Murray SM, Gerontology M, Ther GR, Sherrington C. The effect of an individualized fall prevention program on fall risk and falls in older people: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(8):1296–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paloski WH, Black FO, Reschke MF, Calkins DS, Shupert C. Vestibular ataxia following shuttle flights: effects of microgravity on otolith-mediated sensorimotor control of posture. Am J Otol. 1993;14(1):9–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lang T, LeBlanc A, Evans H, Lu Y, Genant H, Yu A. Cortical and trabecular bone mineral loss from the spine and hip in long-duration spaceflight. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(6):1006–12. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ensrud KE, Ewing SK, Taylor BC, Fink HA, Stone KL, Cauley JA, Tracy JK, Hochberg MC, Rodondi N, Cawthon PM. Frailty and risk of falls, fracture, and mortality in older women: the study of osteoporotic fractures. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(7):744–51. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.7.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rousseau P. Immobility in the aged. Arch Fam Med. 1993;2(2):169–77. doi: 10.1001/archfami.2.2.169. discussion 178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edgerton VR, Zhou MY, Ohira Y, Klitgaard H, Jiang B, Bell G, Harris B, Saltin B, Gollnick PD, Roy RR, et al. Human fiber size and enzymatic properties after 5 and 11 days of spaceflight. J Appl Physiol. 1995;78(5):1733–9. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.78.5.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meyer PF, Oddsson LI, De Luca CJ. The role of plantar cutaneous sensation in unperturbed stance. Exp Brain Res. 2004;156(4):505–12. doi: 10.1007/s00221-003-1804-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Layne CS, Mulavara AP, McDonald PV, Pruett CJ, Kozlovskaya IB, Bloomberg JJ. Effect of long-duration spaceflight on postural control during self-generated perturbations. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90(3):997–1006. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.3.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernie GR, Gryfe CI, Holliday PJ, Llewellyn A. The relationship of postural sway in standing to the incidence of falls in geriatric subjects. Age Ageing. 1982;11(1):11–6. doi: 10.1093/ageing/11.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maki BE, Holliday PJ, Topper AK. A prospective study of postural balance and risk of falling in an ambulatory and independent elderly population. J Gerontol. 1994;49(2):M72–84. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Helden S, van Geel AC, Geusens PP, Kessels A, Nieuwenhuijzen Kruseman AC, Brink PR. Bone and fall-related fracture risks in women and men with a recent clinical fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(2):241–8. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Notomi T, Lee SJ, Okimoto N, Okazaki Y, Takamoto T, Nakamura T, Suzuki M. Effects of resistance exercise training on mass, strength, and turnover of bone in growing rats. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2000;82(4):268–74. doi: 10.1007/s004210000195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawanabe K, Kawashima A, Sashimoto I, Takeda T, Sato Y, Iwamoto J. Effect of whole-body vibration exercise and muscle strengthening, balance, and walking exercises on walking ability in the elderly. Keio J Med. 2007;56(1):28–33. doi: 10.2302/kjm.56.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubin C, Turner AS, Mallinckrodt C, Jerome C, McLeod K, Bain S. Mechanical strain, induced noninvasively in the high-frequency domain, is anabolic to cancellous bone, but not cortical bone. Bone. 2002;30(3):445–52. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00689-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubin C, Turner AS, Muller R, Mittra E, McLeod K, Lin W, Qin YX. Quantity and quality of trabecular bone in the femur are enhanced by a strongly anabolic, noninvasive mechanical intervention. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17(2):349–57. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.2.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilsanz V, Wren TA, Sanchez M, Dorey F, Judex S, Rubin C. Low-level, high-frequency mechanical signals enhance musculoskeletal development of young women with low BMD. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21(9):1464–74. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Costantino C, Pogliacomi F, Soncini G. Effect of the vibration board on the strength of ankle dorsal and plantar flexor muscles: a preliminary randomized controlled study. Acta Biomed. 2006;77(1):10–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubin CT, Capilla E, Luu YK, Busa B, Crawford H, Nolan DJ, Mittal V, Rosen CJ, Pessin JE, Judex S. Adipogenesis is inhibited by brief, daily exposure to high-frequency, extremely low-magnitude mechanical signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(45):17879–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708467104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garman R, Gaudette G, Donahue LR, Rubin C, Judex S. Low-level accelerations applied in the absence of weight bearing can enhance trabecular bone formation. J Orthop Res. 2007;25(6):732–40. doi: 10.1002/jor.20354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evaluation of Homan Exposure to Whole Body Vibration. ISO 2631/1. International Standards Organization; Geneva: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins JJ, De Luca CJ. Open-loop and closed-loop control of posture: a random-walk analysis of center-of-pressure trajectories. Exp Brain Res. 1993;95(2):308–18. doi: 10.1007/BF00229788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melzer I, Benjuya N, Kaplanski J. Postural stability in the elderly: a comparison between fallers and non-fallers. Age Ageing. 2004;33(6):602–7. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afh218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simmons RW, Richardson C, Pozos R. Postural stability of diabetic patients with and without cutaneous sensory deficit in the foot. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1997;36(3):153–60. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(97)00044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel M, Talish R, Rubin C, Jo H. Low magnitude and high frequency mechanical loading prevents decreased bone formation responses of 2t3 preosteoblasts. J Bio Chem. 2009;106:306–16. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luu Y, Capilla E, Rosen C, Gilsanz V, Pessin J, Judex S, Rubin CT. Mechanical Stimulation of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Proliferation and Differentiation Promotes Osteogenesis While Preventing Dietary Induced Obesity. J Bone Miner Res. 2008 doi: 10.1359/JBMR.080817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xie L, Rubin C, Judex S. Enhancement of the adolescent murine musculoskeletal system using low-level mechanical vibrations. J Appl Physiol. 2008;104(4):1056–62. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00764.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.LeBlanc A, Schneider V, Shackelford L, West S, Oganov V, Bakulin A, Voronin L. Bone mineral and lean tissue loss after long duration space flight. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2000;1(2):157–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kouzaki M, Masani K, Akima H, Shirasawa H, Fukuoka H, Kanehisa H, Fukunaga T. Effects of 20-day bed rest with and without strength training on postural sway during quiet standing. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2007;189(3):279–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2006.01642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis JE, Horwood KE, DeJong GK. Effects of exercise during head-down bed rest on postural control. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1997;68(5):392–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]