Abstract

Tracking a digital pursuit rotor task was used to measure dual task costs of language production by young and older adults. Tracking performance by both groups was affected by dual task demands: time on target declined and tracking error increased as dual task demands increased from the baseline condition to a moderately demanding dual task condition to a more demanding dual task condition. When dual task demands were moderate, older adults’ speech rate declined but their fluency, grammatical complexity, and content were unaffected. When the dual task was more demanding, older adults’ speech, like young adults’ speech, became highly fragmented, ungrammatical, and incoherent. Vocabulary, working memory, processing speed, and inhibition affected vulnerability to dual task costs: vocabulary provided some protection for sentence length and grammaticality, working memory conferred some protection for grammatical complexity, and processing speed provided some protection for speech rate, propositional density, coherence, and lexical diversity. Further, vocabulary and working memory capacity provided more protection for older adults than for young adults although the protective effect of processing speed was somewhat reduced for older adults as compared to the young adults.

Keywords: aging, speech, language production, dual task demands, individual differences

In everyday life, we commonly perform multiple tasks at once, dividing attention among competing activities and situations. Dual-tasking or multi-tasking is pervasive; we eat while driving, prepare meals while watching television, and listen to the radio while reading the newspaper and eating breakfast. Theoretically, researchers have sought to determine whether dual task costs reflect the operation of a central bottleneck in response selection (Pashler, 1994) or strategic differences in task coordination (Meyer & Kieras, 1997a, 1997b). This debate has focused on questions of practice and automaticity, given that practice should reduce dual task costs by permitting parallel processing in the Meyer and Kieras framework. Recent investigations (see meta-reviews by Riby, Perfect, & Stollery, 2004, and Verhaeghen, Steitz, Sliwinski, & Cerella, 2003) suggest that older adults experience greater dual task costs than young adults, especially with tasks that involve controlled processing or executive functions such as task switching, time-sharing, and updating. Gőthe, Oberauer, and Kliegl (2007) suggest that there are persistent differences in how young and older adults combine even two well-practiced tasks. Gőthe et al. have suggested that older adults adopt a “conservative” approach to managing dual task demands by trading reduced speed for improved accuracy, whereas young adults employ a “risky” approach by emphasizing speed over accuracy.

Talking is one of the most well-practiced tasks for both young and older adults and is often combined with other activities, particularly gross motor activities: we converse while watching television, carry on a conversation while walking, or talk with our passengers while driving a car. Becic, Dell, Bock, Garnsey, Kubose, and Kramer (2010) have shown that both story retelling and driving performance are affected when individuals attempt to retell a story told to them while they were navigating through an urban environment in a driving simulator. And in a prior study, Kemper, Schmalzried, Herman, Leedahl, and Mohankumar (2008) demonstrated that simultaneously performing even a simple visual-motor task can be costly to the speech of young and older adults. Kemper et al. combined pursuit rotor tracking (McNemar & Biel, 1939) with concurrent talking to assess age differences in dual task costs. The costs of concurrent talking for pursuit tracking were similar for young and older adults: tracking performance, as measured by average time on target and average distance from the target, declined when the participants were talking while tracking as compared to baseline condition. However, tracking had different costs for language production in the two groups. Although both groups spoke more slowly in the dual task condition than in the baseline condition, young adults experienced greater dual task costs to speech than did older adults, consistent with prior research (Kemper et al., 2003, 2005). In particular, concurrent tracking impaired young adults’ verbal fluency and grammatical complexity, such that young adults used shorter, simpler sentences under dual task conditions than they did in the baseline condition. Surprisingly, older adults were less vulnerable to dual task demands than young adults, in that concurrent tracking slowed older adults’ speech but did not otherwise affect their fluency, grammatical complexity, or linguistic content, as compared to the baseline condition.

Young adults generally use a complex speech style that differs from that used by older adults in several ways (Kemper, Kynette, Rash, O’Brien, & Sprott, 1989): Young adults speak more rapidly and tend to use more lexical fillers such as “like” and “you know” than do older adults; Young adults also tend to use a more limited vocabulary than older adults, partially as a result of their frequent repetition of lexical fillers; young adults are also able to vary their speech, adopting a form of speech sometimes termed “elderspeak” when addressing older adults or adults assumed to have cognitive impairments (Kemper, Ferrell, Harden, Finter-Urczyk, & Billington, 1998a; Kemper, Finter-Urczyk, Ferrell, Harden, Billington, 1998b). This “elderspeak” style is slower and uses shorter, simpler sentences and is marked by a high degree of repetition and redundancy.

In contrast, older adults use a restricted speech style, one that is marked by a slower rate of speech and the use of short, grammatically simple sentences with few lexical fillers but a diverse vocabulary. Older adults tend to maintain this same speech style when confronted with different conversational partners, even ones assumed to be cognitively impaired (Kemper et al., 1998a). When participants are provided with the basic elements (nouns and verbs) from which to construct a sentence, those produced by older adults are slower, simpler and shorter than those produced by young adults (Kemper, Herman, Lian, 2003b; Kemper, Herman, Liu, 2004). For example, Kemper, Herman, and Lian (2003b) gave young and older adults 2, 3 or 4 words and asked them to produce a sentence. Older adults’ responses were similar to those of younger adults when given 2 or 3 words. When given 4 words, the older adults made more errors and their responses were shorter, grammatically simpler, and propositionally less informative than the young adults’ responses. Older adults’ restricted speech style thus appears to be an accommodation to age-related declines in working memory and processing speed (Kemper & Sumner, 2001). Processing limitations, arising from reduced working memory, and/or slowed processing speed, impose a “functional ceiling” that limits the fluency, complexity, and informativeness of older adults’ speech.

Young adults’ rapid, complex speech leaves them vulnerable to dual task demands (Kemper et al., 2008). When they are challenged to speak while engaged in a secondary task, they not only slow down but reduce their grammatical complexity. In contrast, older adults’ restricted speech type appears to reduce their vulnerability to dual task demands. Slowing down enables them to maintain this restricted speech style while engaged in a concurrent activity without a further loss of grammatical complexity. However, there may be limits to older adults’ ability to maintain their restricted speech style. When dual task demands exceed some threshold, simply slowing down may not be enough to preserve older adults’ ability to plan and produce fluent, well-formed, informative speech. As a result, speech planning and production may break down, resulting in fragmented, ungrammatical, incoherent speech. Further, older adults who are experiencing problems with working memory, processing speed, or other cognitive abilities may be especially vulnerable to dual task demands.

Many aspects of language processing have been linked to individual differences in cognitive abilities such vocabulary knowledge (Lewellen, Goldinger, Pisoni, & Greene, 1993; MacDonald & Christiansen, 2002; Martin, Ewert, & Schwanenflugel, 1994;), working memory (Acheson & MacDonald, 2009; Caplan & Waters, 1999; Daneman & Carpenter, 1980; Just & Carpenter, 1992; Kemper, Kemtes, & Crow, 2004; Swets, Desmet, Hambrick, & Ferreira, 2007), processing speed (Stine, 1990; Stine, Wingfield, & Poon, 1986; Stine-Morrow, Loveless, & Soderberg, 1996; Wingfield, Tun, & Rosen, 1995), and inhibitory control (Connelly, Hasher, & Zacks, 1991; Hasher & Zacks, 1988; Tun, O’Kane, & Wingfield, 2002; Zacks & Hasher, 1997). Although vocabulary knowledge increases over the lifespan (Verhaeghen, 2003), most models of cognitive aging assume that working memory, processing speed, and inhibitory control decline (Park, Lautenschlager, Hedden, Davidson, Smith, & Smith, 2002), contributing to language processing problems of older adults .

While the role of working memory during language processing has received the most attention, some research has attempted to differentiate the effects of working memory from those of processing speed and inhibition. For example, Kwong See and Ryan (1996) examined how individual differences working memory capacity, processing speed, and efficiency of inhibitory processes, estimated by backward digit span, color naming speed, and Stroop interference, respectively, affected text processing by young and older adults. Their analysis suggested that older adults’ text processing difficulties can be attributed to slower processing and less efficient inhibition, rather than to working memory limitations. Similarly, Van der Linden, et al. (1999) sought to distinguish the effects of working memory limitations from those due to reductions of processing speed or a breakdown of inhibitory processes by examining performance on a wide range of language tasks using structural equation modeling. Young and older adults were tested on their ability to understand texts and recall sentences and words. They were also given a large battery of tests designed to measure processing speed, working memory capacity, and the ability to inhibit distracting thoughts. The analysis indicated that these three general factors (speed, working memory, inhibition) did account for age-differences in performance on the language processing tasks. Further, their analysis indicated that “age-related differences in language, memory and comprehension were explained by a reduction of the capacity of working memory, which was itself influenced by reduction of speed, [and] increasing sensitivity to interference…” (p. 48).

Individual differences in working memory, processing speed, and other cognitive abilities may contribute not only to age group differences in language processing but also to age group differences in responding to dual task demands. Faster individuals may be able to more rapidly execute individual tasks as well as switch more rapidly between tasks; individuals with greater working memory capacity may not only have a greater capacity for maintaining information in a short-term buffer but also a greater capacity for maintaining multiple, distinct buffers. Individuals with better inhibitory control may not only be better able to ignore distractions but also better able to shift attention between tasks or to divide attention between tasks. A better vocabulary may confer an overall advantage for lexical diversity as well as provide some protection from task-specific intrusions and perseverations.

Kemper et al. (2008) found that older adults’ working memory capacity predicted how well were they were able to maintain grammatical complexity in the dual task condition. Kemper et al. also found that slower individuals were better able to maintain words-per-minute speech rates in the dual task condition. These findings suggest that the slower, “conservative” speech strategy may reduce older adults’ vulnerability to dual task demands. Vocabulary and inhibitory control did not appear to provide any protection from dual task for either young or older adults. However, these findings must be viewed cautiously since the study was limited to a small number of participants and a small number of measures of cognitive ability, and the task demands were moderate and may not have sufficiently challenged the participants’ ability to dual-task.

The present study was designed to examine the limits of older adults’ vulnerability to dual task demands, extending the approach of Kemper et al. (2008) in two ways: first, dual task difficulty was manipulated to determine the limits of older adults’ restricted speech style; second, group comparisons were supplemented with an analysis of individual differences to assess vulnerability in dual task performance. In this study, performance on baseline tests of pursuit rotor tracking and language production was contrasted with performance in two dual task conditions, (1) a moderately difficult condition that required participants to talk while tracking a pursuit rotor moving at the same speed as in the baseline condition, and (2) a more demanding condition in which the participants talked while rotor speed was accelerated to 150% of the baseline speed. Rotor performance was assessed by the average time-on-target (the percentage of time participant were successful in tracking the moving target) and average tracking error (the average distance from the moving target). Language production was assessed by nine measures of verbal fluency, grammatical complexity, and linguistic content in the speech samples collected in the baseline and two dual task conditions. In addition, an expanded battery of cognitive tests was administered to the young and older adults in order to more thoroughly assess whether individual differences in vocabulary, working memory, processing speed, and inhibition would moderate older adults’ vulnerability to dual task demands. Latent factor scores, rather than single indicators, were used to assess individual differences in vocabulary, working memory, and processing speed and a composite of two common tests was used to assess inhibition. In addition, testing was extended to a large panel of participants.

Method

Participants

A total of 100 young adults (18 to 28 years old, M = 21.1, SD = 2.8) and 97 older adults (65 to 85 years old, M = 73.6, SD = 7.8) were tested. Young adults were recruited by signs posted on campus and class announcements; older adults were recruited from a database of prospective and previous research participants. Participants were paid $10/hour. Older adults were also compensated for driving to and from the testing site. Data from three additional older adults were lost due to technical problems during testing.

Cognitive Measures

As detailed below, participants were given a battery of cognitive tests to assess individual differences in four constructs assumed to contribute to age-related differences in cognition: vocabulary, working memory, processing speed, and inhibition. Table 1 summarizes the means, standard deviations, and age group comparisons for each observed measure; an alpha level of .05 was set for these and all subsequent t and F tests.

Table 1. Latent Factor Scores and Univariate Measures of Tests of Vocabulary, Working Memory, Processing Speed, and Inhibition for the two Groups of Young and Older Adults.

| Young Adults | Older Adults | F (1,195) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Vocabulary | < − 0.01 |

4.84 | 9.66 | 6.99 | |

| Years of Education | 16.2 | 0.7 | 17.1 | 2.9 | 1.89 |

| North American Reading Test | 31.0 | 5.3 | 36.3 | 7.4 | 33.29** |

| Shipley Vocabulary | 31.8 | 3.2 | 34.9 | 3.4 | 46.78** |

| Working Memory | < − 0.01 |

4.98 | −12.88 | 4.13 | |

| Digits Forward | 9.3 | 2.2 | 7.7 | 2.4 | 4.31* |

| Digits Backward | 7.7 | 2.4 | 5.2 | 0.7 | 7.68* |

| Reading Span | 3.5 | 0.8 | 3.1 | 0.6 | 12.43** |

| Operation Span | 4.0 | 0.9 | 2.7 | 1.2 | 73.45** |

| Processing Speed | 0.0 | 0.61 | −1.99 | 0.72 | |

| Digit Symbol | 35.1 | 4.7 | 24.4 | 5.2 | 229.16** |

| Stroop Xs | 89.1 | 14.2 | 69.8 | 13.9 | 92.76** |

| Trail Making A | 45.7 | 10.0 | 78.4 | 28.5 | 108.39** |

| Inhibition | −0.18 | 0.13 | −0.38 | 0.21 | |

| Stroop words | 66.5 | 12.8 | 39.3 | 11.8 | 43.28** |

| Stroop Interference % | − 25.5 |

0.10 | −42.1 | .15 | 83.89** |

| Trail Making B | 51.8 | 12.9 | 104.3 | 24.8 | 18.46** |

| Trail Making Interference % | −10.4 | 2.7 | −38.2 | 3.8 | 23.41** |

p < .05

p < .01

Three indicators of vocabulary were collected. On the Shipley (1940) Vocabulary Test, participants must choose the best synonym from 4 choices and the number correct out of 40 words served as the outcome. On the North American Reading Test (AmNART; Grober & Sliwinski, 1991), participants were asked to read aloud a series of irregularly spelled words and the number of correctly pronounced words (out of 50 possible) was the outcome. Finally, educational attainment in years served as a third indicator of vocabulary.

Four indicators of working memory were collected. On the Digits Forward and Digits Backwards tests (Wechsler, 1958), participants repeated strings of numbers, either in the same (forward) or reverse (backward) order as presented. String length increased from 2 digits to a maximum of 9 digits. Two strings at each length were given to the participants, and the number repeated correctly out of 14 strings was the outcome. On the Daneman and Carpenter (1980) Reading Span Test, participants were asked to remember the last word of each sentence in a set; the number of sentences per set, hence the number of words to be remembered, increased. The maximum number of words a participant could recall out of 7 determined their Reading Span. Finally, on the Operation Span task (OSPAN; Turner & Engle, 1989), participants read an arithmetic equation out loud, responded whether the equation was correct, then read a word printed beside the equation. The number of equations, hence the number of words to be remembered, increased. The maximum number of words a participant could recall out of 5 determined their OSpan.

Three indicators of processing speed were collected. In the Digit Symbol Test (Wechsler, 1958), participants were given a key pairing symbols to digits. The number of symbols correctly paired with a digit within 45 seconds served as the outcome. On the baseline condition of the Stroop test (Stroop, 1935), participants had 45 seconds to name the color of the ink of a series of X’s, and number correct served as the outcome. Finally, on the Trails A portion of the Trail Making test (Reitan, 1958), participants connected labeled dots in numerical order, and the total time in seconds required to correctly connect the dots served as the outcome.

Lastly, the Stroop and Trail Making Tests were also used to derive two measures of inhibition. First, in addition to the baseline block X’s condition of the Stroop test, participants were given a second condition requiring them to name the color of the ink of printed color words (e.g. the word RED printed in green ink). A Stroop interference score was then calculated as shown in Equation (1):

| (1) |

Second, in addition to the Trails A test, on the Trails B test, participants connected labeled dots in sequential order, alternating between letters and numbers (1-A-2-B-3-C and so on). A Trail Making interference score was calculated as shown in Equation (2):

| (2) |

Because only 2 measures of inhibition were available, the Stroop and Trail Making interference scores were averaged for each participant to create a summary measure.

Tests of Age Invariance in Factor Structure

Following the procedures recommended by Vandenberg and Lance (2000), 3 latent factors for vocabulary, working memory, and processing speed were estimated and evaluated for measurement equivalence across age groups in a series of 4 increasingly restrictive models: (1) configural invariance of factor structure, (2) metric invariance of factor loadings, (3) scalar invariance of item intercepts, and (4) invariance of residual variances. The baseline 3-factor model in which all parameters were allowed to differ across groups fit well, χ2 (64) = 89.069, CFI = .952, RMSEA = .063, CI = .026 to .093, indicating that configural invariance was achieved. At the second step, partial metric invariance was obtained: the factor loadings for Trails A, Digits Backwards, and education differed significantly across groups, likely reflecting a lack of variance in Trails A and education for the young adults and in Digits Backwards for the older adults. Partial scalar invariance was then obtained: the intercepts for the AmNART, Digits Forwards, and Reading Span tests differed significantly across groups. Finally, the residual variances for OSpan, Digits Forward, and Reading Span differed significantly across groups. Consequently, Empirical Bayes estimates for vocabulary, working memory, and processing speed latent factor scores were derived from this final model separately for each age group for use in subsequent analyses.

Pursuit-Rotor Tracking

Participants were trained on a digital pursuit rotor tracking task developed by the Digital Electronics and Engineering Core of the Biobehavioral Neurosciences and Communication Disorders Center, a component of the Schiefelbusch Institute for Life Span Studies at the University of Kansas. The pursuit rotor featured a bull’s-eye target that rotated along an elliptical track. Participants used a trackball mouse to track the target, displayed on a 15” high resolution flat-screen. The pursuit rotor was controlled by a separate laptop computer. At the start of a trial, participants saw a red bull’s-eye target, 24 pixels in diameter, and an elliptical track and were instructed to position a pair of cross-hairs over the target using the trackball, which turned the target from red to green. When the target started moving along the track after a 3 sec delay, participants tracked the moving target, attempting to keep the cross-hairs superimposed on the target. The experimenter set the speed at which the target rotated along the track as well as the duration of the trial. The speed could be varied from approximately .2 to 2 revolutions per minute; trial duration could be varied from 30 sec to 4 min or longer. The program sampled the location of the cross-hairs every 100 ms, and determined whether they were centered on the target, and if not, their distance (in pixels) from the center of the target. The probability that the cross-hairs were on-target was averaged over 3 successive 100 ms intervals, and a moving average, time on target, was determined. This moving average could be computed for the duration of the entire trial or for any portion of the trial. In addition, a second measure of tracking performance, tracking error, was computed as the distance in pixels from of the center of the target to the cross-hairs, averaged over 3 successive 100 ms intervals; a moving average was determined over successive intervals for the entire trial or for any segment of the trial. A second version allowed the continuous tracking record to be time-locked to a digital recording of the speech sample produced by the participants. The speech wave form was synchronized with the tracking record and was then used to segment the trial to mark the onset and offset of the participants’ speech.

Pursuit Rotor Training

Participants were initially trained on the pursuit rotor task to an asymptotic performance level. Initial tracking speed was selected based on pilot testing. Initial tracking speeds for young and older adults were set at 1.2 and 0.45 rev per min, respectively. Participants practiced tracking for 30 sec and received feedback on their performance. A “2 up/1 down stair-case” training procedure was used to gradually increase tracking speed on successive 30 sec trials: if average time on target was 80% or better for a trial, the speed was increased by 10% for the next trial; if less than 80%, the speed was decreased by 5%. The stair-case procedure converged on an asymptotic tracking speed when the speed oscillated around the same value, moving “up” and “down” past this value 3 times.

In general, young adults took more trials to reach an asymptotic tracking speed (MY = 22.8 trials, SDY = 6.1) than did older adults (MO = 18.5 trials, SDO = 5.4), F(1,195) = 27.34, p < .01. Given their slower starting rate, older adults’ tracking speed was changed in smaller increments, and therefore the older adults reached asymptotic levels more quickly than young adults. After training, the young adults’ asymptotic tracking speed (MY = 2.3 rev/min, SDY = 0.9) was faster than the older adults’ (MO = 0.9 rev/min, SDO = 0.6), F(1,195) = 306.66, p < .01. However, relative to starting speed, the older adults had improved 200% after training whereas the young adults had improved 191%. After the asymptotic tracking speed was established for each participant, participants were given a 4 min tracking task to establish a baseline of tracking performance. For this 4 min tracking baseline, older adults and young adults were equivalent on time on target (M = 79%, SD = 4) and tracking error (M = 3.7 pixels, SD = .3), both p > .05.

Dual Task Conditions

Following the 4 min tracking baseline, 2 dual task conditions were administered that differed in the speed of the moving target – either using 100% of the baseline speed (moderate condition) or 150% speed (demanding condition). During these dual task conditions, participants first started tracking the rotating target; after either 1 revolution or 1 min had passed, whichever came first, a small window containing a question prompt appeared centered within the track (without obscuring the track, cross-hairs, or target). Participants were instructed to read the prompt aloud and to respond while continuously tracking the moving target for 4 min. The pursuit rotor tracking program recorded tracking performance from the onset of the trial. Using the speech wave form as a guide, the continuous record was segmented to mark the participant’s reading of the prompt and the response. Time on target and tracking error were calculated only when the participant was responding to the question.

Language Samples

A baseline language sample was collected from each participant at the beginning of testing. Participants then received training on pursuit rotor tracking and were tested on baseline tracking; two additional language samples were collected while the participants were engaged in the two dual task conditions. Three eliciting questions were used: Who was the greatest president of the U.S. and why? What do you like the most about living [here] and what do you like the least? What was the most significant invention of the 20th century and how did it affect your life? The three questions were counter-balanced across tasks and participants. Each language sample was approximately 4 min in duration and included at least 50 utterances.

Following the procedures described by Kemper, Kynette, Rash, Sprott, and O’Brien (1989), the language samples were transcribed and coded by segmenting them into utterances and then coding each utterance. Utterances were defined by discernable pauses in the participant’s speech flow; therefore, utterances did not necessarily correspond to grammatically defined sentences but included nonlexical interjections, fillers (speech serving to fill gaps in the speech flow,) and sentence fragments. Lexical fillers, such as “and,” “you know,” “yeah,” “well,” etc. were retained in the transcript. Non-lexical fillers, such as “uh,” “umm,” “duh,” etc., were excluded from the transcript, as were utterances that repeated or echoed the examiner.

The fluency, grammatical complexity, and content of each language sample were then analyzed. Given the large number of language samples, some measures were obtained from two computerized scoring systems, Coh-Metrix (Graesser, McNamara, Louwerse, & Cai, 2004) and CPIDR-3 (Brown, Snodgrass, Kemper, Herman, & Covington, 2008). These computerized measures have been previously validated against conceptually similar measured obtained from trained coders with excellent agreement (see Kemper et al., 2008). Table 2 summarizes the correlations among these measures separately for young and older adults; baseline means and standard deviations are presented in Table 3 along with the dual task results.

Table 2. Correlations among the Baseline Language Sample Measures.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Speech Rate | -- | −.06 | −.12 | .17 | .08 | −.03 | .07 | −.10 | .10 |

| 2. Mean Length Utterance |

−.11 | -- | .09 | .19 | .28** | .30** | .17 | .44** | −.12 |

| 3. Percent with Fillers |

.31** | .41** | -- | −.05 | −.16 | −.03 | −.16 | .15 | −.056 |

| 4. Percent Grammatical |

.10 | .11 | −.12 | -- | .32** | .37** | .12 | .14 | .05 |

| 5. Developmental Level |

−.14 | .26* | −.04 | .16 | -- | .52** | .16 | .01 | .14 |

| 6. Grammatical Index |

−.06 | .25* | .05 | .13 | .55** | -- | .06 | .10 | −.05 |

| 7. Propositional Density |

.16 | .01 | .31** | .13 | .12 | .17 | -- | .46** | .41** |

| 8. Coherence Index |

.14 | .33** | .04 | .02 | −.14 | .09 | .48** | -- | −.19 |

| 9. Type Token Ratio |

−.23* | −.07 | −.41** | .19 | .18 | .13 | .34** | −.13 | -- |

NOTE: Correlations for young adults are reported in the lower-half matrix; those for older adults are reported in the upper-half matrix.

p < .05

p < .01.

Table 3. Age Group Differences on Baseline and Dual Task Measures of Tracking Performance, Fluency, Grammatical Complexity, and Linguistic Content.

| Young Adults | Older Adults | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Dual Task Conditions |

Baseline | Dual Task Conditions |

|||||||||

| Moderate | Demanding | Moderate | Demanding | |||||||||

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | |

| Performance | ||||||||||||

| Time On Task |

79.39a | 0.04 | 68.10 | 1.12 | 25.78 | 1.08 | 78.76a | 1.02 | 70.69 | 0.49 | 24.33 | 0.72 |

| Error | 3.72a | 0.02 | 4.17 | 0.06 | 8.34 | 0.07 | 3.66a | 0.05 | 3.82 | 0.02 | 7.94 | 0.03 |

| Fluency | ||||||||||||

| Speech rate | 121.39 | 2.77 | 100.28 | 2.39 | 68.70 | 2.20 | 97.48 | 2.97 | 84.26 | 2.91 | 60.93 | 2.30 |

| % with Fillers | 55.68 | 3.21 | 24.51 | 1.34 | 21.19 | 1.24 | 5.59a | 0.61 | 5.40a | 0.39 | 5.48a | 0.49 |

| % Grammatical | 51.70a | 0.01 | 43.35 | 0.01 | 39.43 | 0.01 | 49.77a,b | 0.01 | 45.75b | 0.01 | 39.58 | 0.01 |

| Mean Length Utterance |

10.83 | 0.15 | 9.26 | 0.13 | 7.14 | 0.16 | 9.04a | 0.25 | 9.03a | 0.27 | 7.67 | 0.25 |

| Complexity | ||||||||||||

| Developmental Level |

3.91 | 0.07 | 3.25 | 0.09 | 1.45 | 0.10 | 3.50a | 0.10 | 3.29a | 0.10 | 1.33 | 0.10 |

| Grammatical Index |

4.05 | 0.06 | 2.86 | 0.03 | 2. 12 | 0.04 | 3.99a | 0.06 | 3.55a | 0.04 | 3.11 | 0.04 |

| Content | ||||||||||||

| Propositional Density |

51.57a | 0.03 | 61.57 | 0.04 | 35.91 | 0.06 | 53.82a,b | 0.03 | 53.61b | 0.03 | 38.68 | 0.03 |

| Coherence Index |

5.25a | 0.11 | 4.92 | 0.14 | 2.29 | 0.16 | 3.59a,b | 0.14 | 3.51b | 0.16 | 1.37 | 0.13 |

| Type Token Ratio |

0.35a | .01 | .60 | .01 | .51 | .07 | .64 a,b | .01 | .66 b | .01 | .65b | .01 |

NOTE: Within age group, entries sharing the same superscript do not differ at p < .05; between age groups, baselines sharing the same superscripts do not differ at p < .05.

Fluency

Fluency is commonly assumed to involve the coordination of word retrieval, sentence formulation, and articulation processes and to be subject to lapses of attention, memory limitations, and motor and articulatory control problems. There is no generally agreed upon measure of fluency, although fluency is commonly assessed by examining utterance length and grammaticality, speech rate, and the occurrence of fillers. Four measures of fluency were computed. First was the average number of fillers per utterance. Young adults used many fillers and many concatenations of fillers, e.g., “…I mean, like, you know, like… .” Although commonly considered to be disfluencies or speech errors, fillers may serve pragmatic and discourse functions (Cuenca, 2008; Sbisa, 2001). Non-lexical fillers, such as “uh,” “umm,” “duh,” etc., were not tallied although they did affect the calculation of speech rates. Second, all grammatical sentences were identified and the percentage of grammatical sentences was computed for the entire language sample. Third, Mean Length of Utterance (MLU) in words was obtained automatically from the Coh-Metrix program (Graesser et al., 2004). Coh-Metrix was designed to assess the coherence of written texts but can be used to obtain many different linguistic measures from transcripts of oral speech. Finally, a measure of word-per-minute (WPM) speech rate was computed from the average of 3 different 45 sec segments.

Grammatical Complexity

Grammatical complexity reflects syntactic operations involving the use of embedded and subordinate clauses. Two measures of grammatical complexity were obtained from each language sample. First, Developmental Level (DLevel) was scored based on a scale originally developed by Rosenberg and Abbeduto (1987). Grammatical complexity ranged from simple one-clause sentences (DLevel = 0) to complex sentences with multiple forms of embedding and subordination (DLevel = 7). Each complete sentence was scored and the average DLevel for each language sample was then calculated. Second, Coh-Metrix provided the Grammatical Index (GIndex) as a sum of 3 counts per 100 words: the number of connectives such as “because”, “and,” or “if”, the number of noun phrases, and the number of higher level constituents, such as noun phrase complements and relative clauses.

Content

There is no general agreement as to how to best assess the semantic content of a language sample. Semantic content of language samples can be assessed through use of propositions, the overlap or coherence between sentences, or by measuring lexical diversity, redundancy, and repetition. Three measures of linguistic content were obtained from each language sample. First was Propositional Density (PDensity), as calculated by the CPIDR-3 computer program (Brown et al., 2008), in which each utterance was decomposed into its constituent propositions that represent propositional ideas and the relations between them. PDensity was defined as the average number of propositions per 100 words. Second, Coh-Metrix provided a measure of coherence, the Coherence Index (CIndex), as the sum of 2 measures: (1) argument overlap or the proportional of adjacent sentences that share 1 or more nouns, pronouns, or noun phrases, and (2) LSA cohesion. LSA cohesion is based on latent semantic analysis (Landauer, Foltz, & Laham, 1998) which assesses the conceptual similarity of a text relative to that of other texts; in these analyses, the LSA cohesion score measured how conceptually similar each sentence was to all other sentences in the language sample. Conceptual similarity is determined by the overlap of specific words, semantically related words, and words that commonly co-occur (e.g., “President” and “White House”). Finally, Coh-Metrix provided a Type-Token Ratio (TTR) to measure lexical diversity; lower TTRs indicate that many words are repeated throughout the language sample and higher TTRs reflect the use of a greater diversity of words.

Baseline Language Age Comparisons

As shown in Table 2, in the absence of dual task demands, young adults use a different speech style than do older adults. Young adults use many more fillers, peppering their speech with “like,” “well,” and “you know,” and as a result they use longer sentences but have less lexically diverse speech. Their speech is also more rapid and cohesive but less propositionally dense, as fillers contribute little propositional information but do not affect coherence. Although young adults are no more likely to produce grammatical sentences than older adults, they do produce more complex sentences.

Correlations among these baseline measures of fluency, grammatical complexity, and content were computed separately for the young adults and the older adults, as shown in Table 2. Young adults who used more lexical fillers also had lower TTRs, reduced PDensity, and higher MLUs; in contrast, older adults rarely used fillers and their use of fillers was not correlated with PDensity, TTR, and MLU. For both young and older adults, the two measures of grammatical complexity, DLevel and GIndex, were strongly correlated with each other and somewhat correlated with MLU, given that longer sentences tend to be more complex. Two of the content measures, PDensity and CIndex, were also correlated for both groups indicating that speakers who used informationally dense sentences tended to produce more coherent language samples, reflecting greater overlap of ideas, words, and phrases. However, MLU was not correlated with the other fluency measures, and PDensity and CIndex were not correlated with the other measure of semantic content, TTR. Thus, with the exception of grammatical fluency, these results are consistent with prior findings (Cheung & Kemper, 1992; Kemper & Sumner, 2002) suggesting that the structure of verbal abilities in young and older adults is different.

Results

The primary analysis examined how individual differences in vocabulary, processing speed, working memory, and inhibition relate to vulnerability to dual task demands in older adults. The multivariate analysis was conducted in SAS PROC MIXED and proceeded in 2 steps. First, the effects of dual task condition, age group, and their interaction were examined for the rotor tracking measures (time on target, tracking error) as well as the language sample measures of verbal fluency, grammatical complexity, and linguistic content. Second, the effects of individual differences in cognition in predicting vulnerability to dual task demands were assessed across age groups. Table 3 provides the means for each outcome by dual task condition and age group, and Table 4 reports the corresponding significance tests.

Table 4. Results of the Tests of the Fixed Effects for Rotor Performance, Verbal Fluency, Grammatical Complexity, and Linguistic Content Measures.

| Tests of Fixed Effects |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Task Difficulty (2, 194) |

Age Group (1, 195) |

Task Difficulty x Age Group (2, 194) |

|

| Performance | |||

| Time on Task | 2736.57** | <1.0 | 2.28 |

| Error | 6006.49** | <1.0 | 3.08 |

| Fluency | |||

| Speech rate | 341.70 ** | 60.73** | 36.66** |

| % with Fillers | 70.77** | 282.14** | 61.37** |

| % Grammatical | 11.81** | 38.82** | 54.75** |

| Mean Length Utterance | 390.55** | 43.67** | 100.54** |

| Complexity | |||

| Developmental Level | 250.52** | 21.26** | 17.45** |

| Grammatical Index | 2169.48** | 28.10** | 32.34** |

| Content | |||

| Propositional Density | 7908.61** | 339.36** | 1313.81** |

| Coherence Index | 399.96** | 11.18** | 23.08** |

| Type Token Ratio | 5.01* | 11.42** | 14.60** |

p < .05

p < .01

Pursuit Rotor Tracking Outcomes

Rotor tracking performance (time on target, tracking error) by both age groups was affected by dual task demands: time on target declined and tracking error increased as dual task demands increased from the baseline condition to the moderate dual task condition to the demanding dual task condition. Notably, none of the age group main effects or age by task difficulty interactions for the tracking measures were significant, indicating that concurrent talking had similar costs for tracking performance for young and older adults.

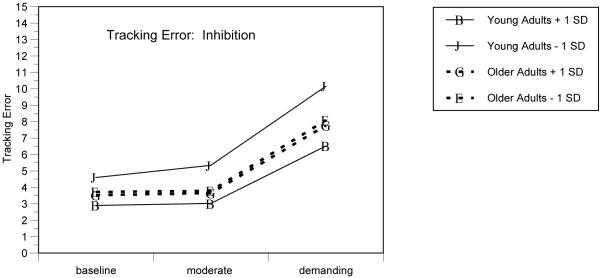

To assess how individual differences in cognition affect pursuit rotor tracking, a series of additional models was then tested. In these models, the factor scores for vocabulary, processing speed, working memory, and composite measure of inhibition were entered as separate predictors of tracking performance in the 3 conditions. Although time on target did not vary with any predictor, tracking error was lower in individuals with better processing speed, F(1, 192) = 4.54, p < .05. The 2-way interactions of processing speed with condition and with age group, as well as the 3-way interaction, were not significant, indicating that the benefits of increased processing speed in reducing tracking error persisted under both dual task conditions and were similar for young and older adults. In addition, tracking error was lower in individuals with better inhibitory control (i.e., who were better able to ignore the distracting words on the Stroop test and alternate between letters and numbers on the Trail Making test), F(1, 192) = 7.43, p < .05. However, as shown in Figure 1, the advantage for tracking error provided by better inhibition was attenuated for older adults, reflecting the significant inhibition by age group interaction, F(1, 192) = 7.40, p < .05. The values plotted in Figure 1 were derived from a model including a 3-way interaction of inhibition, condition, and age group, as evaluated for hypothetical individuals with inhibition factor scores ±1 SD.

Figure 1.

Effect of Individual Differences in Inhibition on Baseline and Dual Task Differences in Tracking Error. Estimates were derived for Young versus Older Adults with Inhibition composite scores ±1 SD.

Language Sample Outcomes

With regard to the language outcomes, as shown in Table 4, the effects of condition were significant for verbal fluency, grammatical complexity, and linguistic content, reflecting increasing dual task costs across conditions, as were the effects of age, generally favoring the younger adults. Also significant, however, were the condition by age group interactions. The speech of young adults became less fluent, less complex, and less informative progressively as dual task demands increased from moderate to demanding, as shown in Table 2. (Curious exceptions are PDensity and TTR, in which propositional density and lexical diversity actually increased in the moderate dual task condition but then decreased in the demanding condition.) Yet a different pattern was evident for older adults: their fluency, grammatical complexity, and linguistic content were resistant to moderate dual task demands, but declined under more demanding dual task conditions. Thus, the two groups converge on similar speech styles in the demanding dual task condition, a speech style characterized by a slow speech rate, many ungrammatical utterances, short, grammatically simple sentences lacking propositional content and coherence but they reached this end-state by dissimilar routes.

The role of individual differences in cognition in predicting vulnerability to dual task demands was then assessed across age groups. Specifically, additional models examined how individual differences in vocabulary, processing speed, working memory, and inhibition related to verbal fluency, grammatical complexity, and linguistic content.

Verbal Fluency

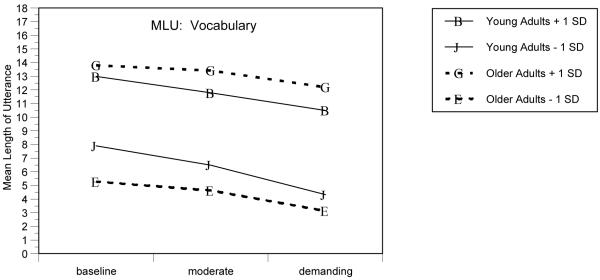

Individual differences in vocabulary significantly predicted MLU, F(1, 192) = 4.72, p < .05, such that those with a larger vocabulary (e.g., who knew more synonyms, could pronounce more irregularly spelled words, and had completed more years of formal education) used longer sentences. Further, individuals with a larger vocabulary were less vulnerable to dual task demands affecting MLU, resulting in the significant vocabulary by condition interaction, F(2, 193) = 4.25, p < .05. The effect of vocabulary on MLU was greater for older adults than for young adults, resulting in the vocabulary by age group interaction, F(1, 192) = 3.92, p < .05. This pattern was constant across conditions, resulting in a non-significant 3-way interaction. These 2 two-way interactions (vocabulary by condition, vocabulary by age) are shown in Figure 2, in which predicted values of MLU are derived from the 3-way interaction model for hypothetical individuals with vocabulary factor scores ±1 SD. Persons with a greater vocabulary also produced a significantly greater percentage of grammatical sentences, F(1, 192) = 6.27, p < .05, but any advantage resulting from superior vocabulary was similar across conditions and for both young and older adults, as shown by the absence of any 2-way and 3-way interactions among vocabulary, condition, and age.

Figure 2.

Effect of Individual Differences in Vocabulary on Baseline and Dual Task Differences on Mean Length of Utterance (MLU). Estimates were derived for Young versus Older Adults with Vocabulary factor scores ±1 SD.

Persons with greater processing speed also spoke significantly faster, F(1, 192) = 5.52, p < .05, although this speed advantage for speech rate was similar across conditions and age groups, as evidenced by the lack of 2-way and 3-way interactions. Finally, the use of fillers was not related to vocabulary, processing speed, working memory, or inhibition. Young adults’ heavy use of fillers appears to be a pragmatic choice; fillers may serve to modulate the pragmatic force of their utterances, functioning like hedges (e.g., “sorta”) and other devices. Young adults with large vocabularies, those who speak rapidly, those with excellent working memory, and those with good inhibition are just as likely to use fillers as those with more limited vocabularies, slower speaking rates, limited working memory, and poor inhibition.

Grammatical Complexity

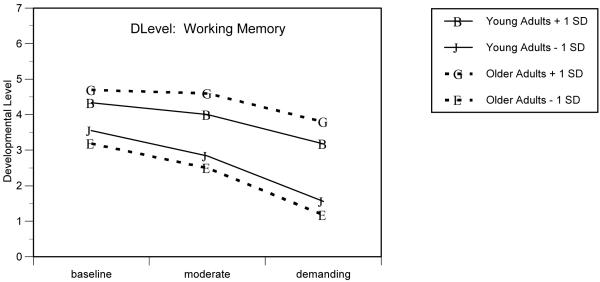

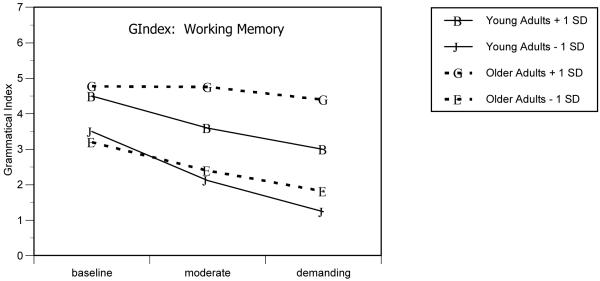

Working memory significantly predicted DLevel, F(1, 192) = 25.51, p < .01, such that persons who recalled more digits and words on the span tests tended to use more complex sentences. Persons with better working memory were less vulnerable to dual task demands, as indicated by a significant interaction of working memory by condition, F(2, 193) = 10.65, p < .01. The effect of working memory on grammatical complexity was greater for older adults than for young adults, resulting in a significant working memory by age group interaction, F(1, 192) = 4.82, p < .05; however, this pattern was constant across conditions, resulting in a non-significant 3-way interaction. These 2-way interactions (working memory by condition, working memory by age) are shown in Figure 3, in which predicted values of DLevel are plotted for hypothetical individuals with working memory factor scores ±1 SD. The same pattern of findings with regard to working memory were evidenced for the other measure of grammatical complexity, GIndex, including a significant main effect, F(1, 192) = 2.84, p > .05, a 2-way interaction with condition, F(2, 193) = 7.60, p < .05, and a 2-way interaction with age group, F(1, 192) = 5.96, p < .05, as shown in Figure 4 (which was constructed similarly to Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of Individual Differences in Working Memory on Baseline and Dual Task Differences on the DLevel measure of Grammatical Complexity. Estimates were derived for Young versus Older Adults with Working Memory factor scores ±1 SD.

Figure 4.

Effect of Individual Differences in Working Memory on Baseline and Dual Task Differences on the Grammatical Index measure of Grammatical Complexity. Estimates were derived for Young versus Older Adults with Working Memory factor scores ±1 SD.

Content

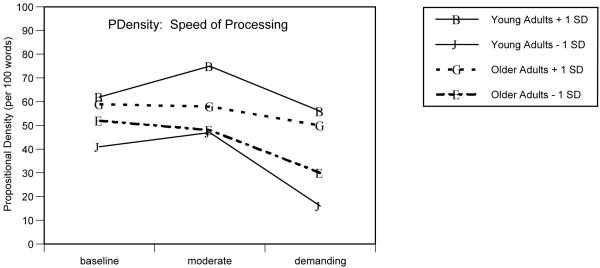

In addition to being more rapid, the speech of persons with greater processing speed was more propositionally dense, PDensity F(1, 192) = 4.93, p < .05, and more cohesive, F(1, 192) = 4.26, p < .05. This suggests that faster individuals may more rapidly access long-term memory information, search semantic memory, and organize their thoughts than slower individuals. Although the 2-way interactions of processing speed with condition or age were not significant, the 3-way interaction was significant for PDensity, F(2, 192) = 4.24, p < .05. In the young adults, propositional density actually improved when dual task costs were moderate; this increase may be attributable to the reduction in young adults’ use of fillers in the dual task conditions. Fillers contribute little propositional content but add words, thereby reducing propositional density. Although fillers are often considered a marker of disfluency, this pattern suggests that young adults may be using fillers to serve pragmatic functions that are disrupted by dual task demands. However, as Figure 5 indicates (constructed as described previously), young adults are unable to maintain this gain in propositional density when dual task demands increased further and also show a greater effect of processing speed on propositional density than older adults. However, the speech of faster older adults is denser than that of slower older adults. Further, moderate dual task demands do not affect the density of older adults’ speech, although the more demanding dual condition resulted in a reduction of older adults’ propositional density, especially for the slower ones.

Figure 5.

Effect of Individual Differences in Speed of Processing on Baseline and Dual Task Differences on the Propositional Density measure of Linguistic Content. Estimates were derived for Young versus Older Adults with Processing Speed factor scores ±1 SD.

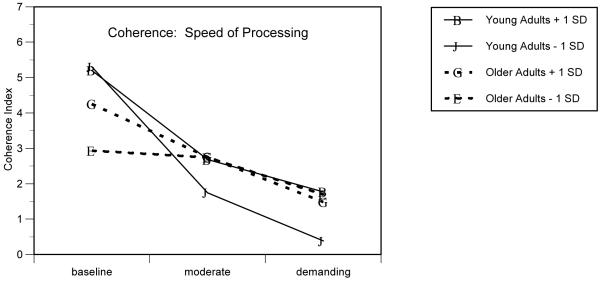

Coherence was also affected by processing speed, as shown in Figure 6, reflecting the significant 3-way interaction of processing speed, age group, and condition, F(2, 193) = 3.03, p < .05. The effect of processing speed on coherence was attenuated for older adults in the 2 dual task conditions although faster older adults had more cohesive speech than slower older adults in the baseline condition. Young adults exhibited a different pattern: the effect of processing speed was attenuated in the baseline condition but emerged in the dual task conditions, such that faster young adults were better able to maintain the coherence of their speech as tracking speed increased. Nonetheless, the speech of young adults, like that of older adults, became less cohesive as dual task demands increased.

Figure 6.

Effect of Individual Differences in Speed of Processing on Baseline and Dual Task Differences on the Coherence Index measure of Linguistic Content. Estimates were derived for Young versus Older Adults with Processing Speed factor scores ±1 SD.

Finally, processing speed also significantly affected lexical diversity, measured by TTR, F(1, 192) = 4.09, p < .05, such that those who responded faster on the baseline Stroop and Trail Making tests used a greater diversity of words, resulting in higher TTRs, than those who responded more slowly. This pattern was constant across conditions and age groups, as indicated by the nonsignificant 2-way interactions. However, there was a marginally significant 3-way interaction, F(2, 193) = 2.99, p = .0555, such that young adults’ TTRs first increased when dual task costs were moderate, then declined when dual task costs were more demanding and this pattern was somewhat attenuated for slower young adults. In contrast, older adults’ TTRs were consistent regardless of dual task demands, although relatively faster older adults did have higher TTRs than slower older adults.

Discussion

This study has examined how aging and vocabulary, working memory, processing speed, and inhibition affect vulnerability to dual task demands. Pursuit rotor tracking, a demanding task by itself, becomes more demanding when it is combined with another task, and even more demanding as the speed of the pursuit rotor is increased. In this study, as tracking demands increased, time on target declined and tracking error increased, demonstrating the effectiveness of the dual task tracking plus talking paradigm. Pursuit rotor tracking varied with processing speed and inhibition: Faster individuals had an overall advantage which was similar for both young and older adults. Individuals with superior inhibition were somewhat less vulnerable to the effects concurrent speech on tracking performance and this protective effect was somewhat attenuated for older adults. However, the overall pattern was the same for both young and older adults regardless of individual differences in processing speed and inhibition: tracking performance deteriorates with dual task demands.

The primary focus of this research was to investigate how language production is affected by aging, dual task demands, and cognitive abilities. Young and older adults adopted different strategies in order to respond to an elicitation question while engaged in pursuit rotor tracking. Yet, ultimately in the most demanding dual task condition, both young and older adults used a similar speech style, one composed of many ungrammatical fragments and short, simple, incoherent sentences.

Young adults’ baseline speech was peppered with many lexical fillers, which perhaps serve pragmatically as hedges to weaken the force of their assertions (Cuenca, 2008; Sbisa, 2001). They spoke rapidly and used long sentences with many complex constructions. Their speech was cohesive but not propositionally dense as a result of their excessive use of fillers. But when asked to speak while engaging in pursuit rotor tracking, their speech became slower, shorter, less complex, and less cohesive. They also reduced but did not completely abandon their use of fillers.

In the baseline condition, older adults used a restricted speech style involving few grammatically complex sentences. When pursuit rotor tracking demands were moderate, they were able to maintain their speech style by speaking more slowly. But under the more demanding tracking condition, they tried to maintain their speech style by speaking yet more slowly but they were unsuccessful in doing so: their speech became less grammatical, less complex, and less cohesive than in the baseline and moderate tracking conditions. Indeed, in the demanding dual task condition, the speech of older adults, like that of young adults, was composed of many ungrammatical fragments, short simple sentences, sentences that were lacking in propositional density and coherence.

Vocabulary, processing speed, working memory, and inhibition were informative in predicting the baseline speech style of both young and older adults: those with better vocabulary used longer sentences and were more likely to produce grammatical utterances, those with better working memory used more complex sentences, and the speech of faster individuals was denser and more cohesive than the speech of slower individuals. Moreover, vulnerability to dual task demands varied with cognitive ability: vocabulary moderated the effect of tracking demands on sentence length and grammaticality, working memory provided some protection for the effects of tracking demands on grammatical complexity, and processing speed buffered the effects of tracking demands on speech rate, propositional density, coherence, and lexical diversity. Further, superior vocabulary provided more protection for older adults than for young adults for the effect of dual task demands on sentence length. Greater working memory capacity provided more protection for older adults than for young adults for the effects of dual task demands on grammatical complexity. In contrast, the protective effect of better processing speed on propositional density and coherence was somewhat reduced in the older adults as compared to the young adults.

Although these individual and group differences in cognition provided some protection from dual task demands, the overall pattern was similar for both groups and all individuals: both young and older adults spoke more slowly, less fluently, less complexly, and less coherently as dual task demands increased. Individuals with superior vocabulary, working memory, processing speed, or inhibition were vulnerable to dual task demands as were individuals with limited vocabulary, reduced working memory, slower processing speed, or poor inhibition.

This investigation of aging and vulnerability of speech to dual task demands demonstrates that there are limits to older adults’ ability to maintain their simplified speech register. When the going gets tough, or in this case when the rotor speeds up, older adults are no longer able to produce grammatical and coherent speech simply by speaking more slowly. Their speech breaks down, into many sentence fragments and short, grammatically simple sentences that lack semantic cohesion, informativeness, and lexical diversity. These results also demonstrate that young adults’ speech converges on a similar style under demanding dual task conditions, a speech style that is still marked by young adults’ predilection to use lexical fillers but one that is composed of many sentence fragments and short, grammatically simple sentences, and one that is incoherent and uninformative. Speech, even that produced by individuals with superior vocabulary, working memory, processing speed, or inhibition, is vulnerable to dual task demands.

We commonly carry on conversations while engaged in another task, such as driving, walking, or preparing meals. Much of the research on dual-tasking has focused on questions of cognitive architecture, processing strategy, and resource-limitations or on extensions to practical applications such as reducing traffic accidents (Becic, Dell, Bock, Garnsey, Kubose, & Kramer, 2010; Strayer, & Drews, 2004) or falls (Siu, Chou, Mayr, van Donkelaar, Woollacott, 2008). This research, like that of Kemper et al. (2008), demonstrates that a well-practiced activity like talking can be affected by a concurrent task, even a relatively simple one like pursuit rotor tracking. For young adults, the disruption of speech fluency, the reduction of grammatical complexity, and the loss of propositional content and cohesion resulting from a concurrent activity may have few practical consequences apart from some delays and inconveniences.

Similar costs to the speech of older adults may have more serious consequences. Older adults’ attempt to minimize dual task costs by slowing down fails when the secondary task becomes very demanding, resulting in disfluent, fragmented utterances and short, grammatically simple sentences, lacking lexical diversity, propositional content, and semantic cohesion. Speech that is highly fragmented, ungrammatical, incoherent, disrupted by many word finding problems, and repetitive, and redundant is highly stigmatized because it is associated with negative stereotypes of older adults (Hummert, Garstka, Ryan, & Bonnesen, 2004). It resembles the speech of individuals with dementia and other cognitive impairments (Kemper, LaBarge, Ferraro, Cheung, Cheung, & Storandt, 1993; Lyons, Kemper, LaBarge, Ferraro, Balota, & Storandt, 1994). Such speech is dysfunctional in that it results in delays, requests for clarifications, confusions, and other forms of communication breakdown. Ryan, Giles, Bartolucci, and Henwood (1986) and Harwood, Giles, and Ryan (1995) argued communication problems can lead to a downward spiral, resulting in the social isolation of older adults and their disengagement from society, thereby furthering their cognitive decline. This hypothesis has been supported by studies demonstrating a link between the social isolation of older adults and their cognitive decline (Bassuk, Glass, & Berkman, 1999; Fabrigoule, Letenneur, Dartigues, & Zarrouk, 1995; Fratiglioni, Wang, Ericsson, Maytan, & Winblad, 2000; Seaman, 1996). Thus, the effects of dual task demands on older adults’ speech may long-term consequences for older adults by reinforcing negative stereotypes of older adults as cognitive impaired, triggering communication breakdowns, and contributing to older adults’ social disengagement and cognitive decline.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants from the NIH to the University of Kansas through the Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Center, grant number P30 HD-002528, and the Center for Biobehavioral Neurosciences in Communication Disorders (BNCD), grant number P30 DC-005803 as well as by grant RO1 AG-025906 from the National Institute on Aging to Susan Kemper. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. We thank Shalyn Oberle, Deepthi Mohankumar, and Whitney McKedy for their assistance with data collection and analysis and Doug Kieweg of the BNCD for developing the digital pursuit rotor.

References

- Acheson DJ, MacDonald MC. Verbal working memory and language production: Common approaches to the serial ordering of verbal information. Psychological bulletin. 2009;135:50–68. doi: 10.1037/a0014411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassuk SS, Glass TA, Berkman LF. Social disengagement and incident cognitive decline in community-dwelling elderly persons. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1999;131:165–173. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-3-199908030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becic E, Dell GS, Bock K, Garnsey SM, Kubose T, Kramer A. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 2010;17:15–21. doi: 10.3758/PBR.17.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C, Snodgrass T, Kemper S, Herman R, Covington MA. Measuring propositional idea density through part-of-speech tagging. Behavioral Research Methods. 2006;40:540–545. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.2.540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan D, Waters G. Verbal working memory and sentence comprehension. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1999;22:114–126. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x99001788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung H, Kemper S. Competing complexity metrics and adults’ production of complex sentences. Applied Psycholinguistics. 1992;13:53–76. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly SL, Hasher L, Zacks RT. Age and reading: The impact of distraction. Psychology and Aging. 1991;6:533–541. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.6.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca M-J. Pragmatic markers in contrast: The case of well. Journal of Pragmatics. 2008;40:1373–1391. [Google Scholar]

- Daneman M, Carpenter PA. Individual differences in working memory and reading. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Ability. 1980;19:450–466. [Google Scholar]

- Fabrigoule C, Letenneur L, Dartigues JF, Zarrouk M. Social and leisure activities and risk of dementia: A prospective longitudinal study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1995;43:485–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb06093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fratiglioni L, Wang H, Ericsson K, Maytan M, Winblad B. Influence of social network on occurrence of dementia: A community-based longitudinal study. The Lancet. 2000;355:1315–1319. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gőthe K, Oberauer K, Kliegl R. Age differences in dual-task performance after practice. Psychology and Aging. 2007;22:596–606. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.3.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graesser AC, McNamara DS, Louwerse MM, Chai Z. Coh-Metrix: Analysis of text cohesion and language. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers. 2004;36:193–202. doi: 10.3758/bf03195564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grober E, Sliwinski M. Development and validation of a model for estimating premorbid verbal intelligence in the elderly. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 1991;13:933–949. doi: 10.1080/01688639108405109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood J, Giles H, Ryan EB. Aging, communication, and intergroup theory: Social identity and intergenerational communication. In: Nussbaum JF, Coupland J, editors. Handbook of communication and aging research. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1995. pp. 133–159. [Google Scholar]

- Hummert ML, Garstka TA, Ryan EB, Bonnesen JL. The role of age stereotypes in interpersonal communication. In: Nussbaum JF, Coupland J, editors. Handbook of communication and aging research. 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 2004. pp. 91–115. [Google Scholar]

- Hasher L, Zacks RT. Working memory, comprehension, and aging: A review and a new view. In: Bower GH, editor. The Psychology of Learning and Motivation. Vol. 22. Academic; New York: 1988. pp. 193–226. [Google Scholar]

- Just MA, Carpenter PA. A capacity theory of comprehension: Individual differences in working memory. Psychological Review. 1992;99:122–149. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.99.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemper S, Crow A, Kemtes K. Eye fixation patterns of high and low span young and older adults: Down the garden path and back again. Psychology and Aging. 2004;19:157–170. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemper S, Ferrell P, Harden T, Finter-Urczyk A, Billington C. The Use of Elderspeak by Young and Older Adults to Impaired and Normal Older Adults. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. 1998a;5:43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kemper S, Finter-Urczyk A, Ferrell P, Harden T, Billington C. Using Elderspeak with Older Adults. Discourse Processes. 1998b;25:55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kemper S, Herman RE, Lian CHT. The costs of doing two things at once for young and older adults: Talking while walking, finger tapping, and ignoring speech or noise. Psychology and Aging. 2003;18:181–192. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemper S, Herman R, Lian C. Age differences in sentence production. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Science. 2003b;58:260–269. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.5.p260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemper S, Herman RE, Liu CJ. Sentence production by younger and older adults in controlled contexts. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2004;58B:P220–P224. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.5.p220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemper S, Herman RE, Nartowicz J. Different effects of dual task demands on the speech of young and older adults. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. 2005;12:340–358. doi: 10.1080/138255890968466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemper S, Kynette D, Rash S, Sprott R, O’Brien K. Life-span changes to adults’ language: Effects of memory and genre. Applied Psycholinguistics. 1989;10:49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kemper S, LaBarge E, Ferraro R, Cheung HT, Cheung H, Storandt M. On the preservation of syntax in Alzheimer’s Disease: Evidence from written sentences. Archives of Neurology. 1993;50:81–89. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540010075021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong See ST, Ryan EB. Cognitive mediation of discourse processing in later life. Journal of Speech Language Pathology and Audiology. 1996;20:109–117. [Google Scholar]

- Kemper S, Schmalzried R, Herman R, Leedahl S, Mohankumar D. The effects of aging and dual task performance on language production. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. 2008;16:241–259. doi: 10.1080/13825580802438868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemper S, Sumner A. The structure of verbal abilities in young and older adults. Psychology and Aging. 2001;16:312–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landauer T,K, Foltz PW, Laham D. An introduction to latent semantic analysis. Discourse Processes. 1998;25:259–284. [Google Scholar]

- Lewellen MJ, Goldinger SD, Pisoni DB, Greene BG. Lexical familiarity and processing efficiency: Individual differences in naming, lexical decision, and semantic categorization. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1993;122(3):316–330. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.122.3.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li KZH, Lindenberger U, Freund AM, Baltes PB. Memorizing while walking: Age-related differences in compensatory behavior. Psychological Science. 2001;12:230–237. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenberger U, Marsiske M, Baltes PB. Memorizing while walking: Increase in dual-task costs from young adulthood to old age. Psychology of Aging. 2000;15:417–436. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.15.3.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons K, Kemper S, LaBarge E, Ferraro FR, Balota D, Storandt M. Oral language and Alzheimer’s disease: A reduction in syntactic complexity. Aging and Cognition. 1994;2:271–294. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald MC, Christiansen MH. Reassessing working memory: Comment on Just and Carpenter (1992) and Waters and Caplan (1996) Psychological review. 2002;109(1):35–54. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.109.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M, Ewert O, Schwanenflugel PJ. The role of verbal ability in the processing of complex verbal information. Psychological Research/Psychologische Forschung. 1994;56(4):301–309. doi: 10.1007/BF00419660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNemar Q, Biel WC. A square path pursuit rotor and a modification of the Miles pursuit rotor pendulum. Journal of General Psychology. 1939;21:463–465. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer DE, Kieras DE. A computational theory of executive cognitive processes and multiple-task performance: Part 1. Basic mechanisms. Psychological Review. 1997a;104:3–65. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.104.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer DE, Kieras DE. A computational theory of executive cognitive processes and multiple-task performance: Part 2. Accounts of psychological refractory-period phenomena. Psychological Review. 1997b;104:749–791. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.104.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park DC, Lautenschlager G, Hedden T, Davidson NS, Smith AD, Smith PK. Models of visuospatial and verbal memory across the adult life span. Psychology and aging. 2002;17:299–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pashler H. Dual-task interference in simple tasks; data and theory. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:220–244. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan RM. Validity of the Trailing Making test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1958;8:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- Riby LM, Perfect TJ, Stollery BT. The effects of age and task domain on dual task performance: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology. 2004;16:863–891. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg S, Abbeduto L. Indicators of linguistic competence in the peer group conversational behavior of mildly retarded adults. Applied Psycholinguistics. 1987;8:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan EB, Giles H, Bartolucci G, Henwood K. Psycholinguistic and social psychological components of communication by and with the elderly. Language and Communication. 1986;6:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sbisa M. Illocutionary force and degrees of strength in language use. Journal of Pragmatics. 2001;33:1791–1814. [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE. Social ties and health: The benefits of social interaction. Annals of Epidemiology. 1996;6:442–451. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(96)00095-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipley WC. A self-administered scale for measuring intellectual impairment and deterioration. Journal of Psychology. 1940;9:371–377. [Google Scholar]

- Siu K-C, Chou LS, Mayr U, van Donkelaar P, Woollacott MH. Attentional mechanisms contributing to balance constraints during gait: The effects of balance impairments. Brain Research. 2008;1248:59067. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.10.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stine EAL, Wingfield A. How much do working memory deficits contribute to age differences in discourse memory? European Journal of Cognitive Psychology. 1990;2:289–304. [Google Scholar]

- Stine EAL, Wingfield A, Poon LW. How much and how fast: Rapid processing of spoken language in later adulthood. Psychology and Aging. 1986;1:303–311. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.1.4.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stine-Morrow EAL, Loveless MK, Soederberg LM. Resource allocation in on-line reading by younger and older adults. Psychology and Aging. 1996;11:475–486. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.11.3.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strayer DL, Drews FA. Profiles in driver distraction: Effects of cell phone conversations on younger and older drivers. Human Factors. 2004;46:640–649. doi: 10.1518/hfes.46.4.640.56806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1935;18:643–662. [Google Scholar]

- Swets B, Desmet T, Hambrick DZ, Ferreira F. The role of working memory in syntactic ambiguity resolution: A psychometric approach. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2007;136:64–81. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.136.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tun PA, O’Kane G, Wingfield A. Distraction by competing speech in young and older adult listeners. Psychology and Aging. 2002;17:453–467. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.17.3.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner ML, Engle RW. Is working memory capacity task dependent? Journal of Memory and Language. 1989;28:127–154. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg RJ, Lance CE. A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods. 2000;3:4–70. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Linden M, Hupet M, Feyereisen P, Schelstraete M-A, Bestgen Y, Bruyer R, et al. Cognitive mediators of age-related differences in language comprehension and verbal memory performance. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. 1999;6:32–55. [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghen P. Aging and vocabulary score: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging. 2003;18:332–339. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghen P, Steitz DW, Sliwinski MJ, Cerella J. Aging and dual-task performance: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging. 2003;18:443–460. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. The measurement and appraisal of adult intelligence. Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore: 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Welford AT. Aging and human skill. Oxford University Press; London: 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Wingfield A, Lindfield KC. Multiple memory systems in the processing of speech: Evidence from aging. Experimental Aging Research. 1995;21:101–121. doi: 10.1080/03610739508254272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacks R, Hasher L. Cognitive gerontology and attentional inhibition: A reply to Burke and McDowd. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 1997;52B:P274–P283. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52b.6.p274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]