Abstract

Purpose

Post-activation barriers to oncology clinical trial accruals are well documented; however, potential barriers prior to trial opening are not. We investigate one such barrier: trial development time.

Experimental Design

National Cancer Institute Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program (CTEP)-sponsored trials for all therapeutic, non-pediatric Phase I, I/II, II, and III studies activated between 2000–2004 were investigated for an eight-year period (n=419). Successful trials were those achieving 100% of minimum accrual goal. Time to open a study was the calendar time from initial CTEP submission to trial activation. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to calculate unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios, controlling for study phase and size of expected accruals.

Results

37.9 percent (n=221) of CTEP-approved oncology trials failed to attain the minimum accrual goals, with 70.8 percent (n=14) of Phase III trials resulting in poor accrual. A total of 16474 patients (42.5% of accruals) accrued to those studies that were unable to achieve the projected minimum accrual goal. Trials requiring less than 12 months development were significantly more likely to achieve accrual goals (odds ratio, 2.15; 95% CI, 1.29–3.57, P=0.003) than trials with the median development time of 12–18 months. Trials requiring a development time of greater than 24 months were significantly less likely of achieving accrual goals (odds ratio, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.20–0.78, P=0.011) than trials with the median development time.

Conclusions

A large percentage of oncology clinical trials do not achieve minimum projected accruals. Trial development time appears to be one important predictor of the likelihood of successfully achieving the minimum accrual goals.

Keywords: Clinical Trials, Accrual Performance, Development Time, CTEP

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, it is estimated that 1.4 million individuals will be diagnosed with cancer, and over half a million will die each year. Advances in therapeutic treatments have improved the 5-year survival rates over the past four decades,1 yet cancer continues to be the second leading cause of death in Americans, resulting in more deaths than the next five causes combined.2 New and innovative therapeutic approaches to improve the standard of care of cancer patients must be developed and then confirmed through a series of clinical trial phases to ensure both efficacy and safety. Phase I–III trials require sufficient patient enrollment so that not only can the efficacy of the therapeutic agent(s) under investigation be tested with a proper degree of statistical certainty, but also to maximize the generalizability of the findings to the intended patient population. Unfortunately, with only 2–7% of the adult cancer population participating in clinical trials, obtaining sufficient accrual is a known barrier to successful completion of clinical trials.3, 4 Furthermore, it has been shown that the lack of appropriate trials represents a significant barrier to accruing oncology patients.5 Hence, there should be a sense of urgency to develop properly safeguarded oncology trials such that treatments discovered at the bench can be translated effectively and rapidly into improved standard of care.

Understanding the reasons behind low accruing clinical trials is important. However, most of the efforts to reduce barriers to patient accruals have been concentrated on post-activation efforts, that is, after a trial is open for patient enrollment or accrual.6, 7 It is our contention that there are factors involved during trial development that significantly impact accrual performance. We postulate that the calendar time required to transit from letter of intent (LOI) or concept through protocol development to final trial activation is inversely related to the attainment of the accrual goal. Research has shown that the time to develop a phase III oncology trial requires nearly 26 months with intricate collaboration among a diverse set of organizations.8–10 While there are any number of other causes that may be attributed to low accruing clinical trials, development time has been shown to be a well-established and critical factor in the success of a new product across a host of other applications.11

To investigate the effect of trial development time on patient accruals to oncology trials, a retrospective evaluation was conducted on trials sponsored by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program (CTEP). CTEP evaluates approximately 900 out of the 1500 NCI-sponsored studies annually.12 All trials evaluated by CTEP are supported by NCI grants and cooperative agreements awarded to scientific institutions and individuals and are conducted by faculty members and practitioners at those institutions that initiated the trial idea. Trials that request CTEP support must be submitted for review once the concept is formulated. Once the concept or letter of intent (LOI) is approved for development into a completed clinical trials, multiple and parallel tasks including protocol writing, regulatory, scientific and ethics reviews, and financial negotiations take place.8 It is only when all these tasks are completed synchronously is the development of a clinical trial complete. It is this development time and intricate coordination among the many stakeholders that we are interested in investigating. This article uncovers the critical, yet often overlooked, barrier of lengthy trial development time as a major factor negatively correlated with accrual performance in phases I–III CTEP-supported oncology trials.

METHODS

All therapeutic, non-pediatric, phase I, I/II, II, and III oncology trials evaluated by CTEP opened to patient accrual between June 1,2000 and December 31, 2004 in the United States with complete tracking information for development time were eligible. Evaluation of accrual performance was conducted as of December 31, 2008 - allowing for trials to be open to accrual for a minimum of four years. Data were supplied by the CTEP Protocol and Information Office (PIO), which maintains a tracking database of trial activities from concept submission to trial activation. Trials originated in multiple sources including NCI’s Clinical Trials Cooperative Group Program, Comprehensive Cancer Centers, Cancer Centers, and NCI-sponsored Consortiums.

The independent variable, development time, was the difference in calendar days between the date of initial CTEP receipt of LOI or concept and the date the trial was opened for accrual. For simplicity, calendar days were converted into months by dividing the total days by 30.33. It is important to note that this definition of development time does not include the days required to prepare the trial idea into a formal submission to CTEP as the consistency of the data is variable dependent upon the institution where the trial was derived. Previous studies of phase III trials have shown that this initial time can consume between 1 and 10 calendar months.10

The dependent variable, accrual-to-goal percent, was calculated using projected minimum accrual goal and actual trial accrual at trial closure. This provides a liberal estimate of the attainment of the accrual goal because it defines the minimum trial sample size needed to achieve the desired scientific endpoint. The minimum projected accrual goal for each trial is defined within the study design of each trial and highly dependent upon the phase. Specifically, phase I minimum projected accrual goals assumes that the dose limiting toxicity (DLT) is observed at the first dose levels; Phase I/II trials establish minimum projected accruals based on the phase I accrual and updates the minimum accrual when the trial transitions to a phase II trial; Minimum accrual goals for phase II and III trials are based upon the number of accruals required to complete the first stage of the study design. It is noted that the minimum projected accrual goals for phase I, I/II, and II trials are most likely under-estimates as these are the absolute minimums necessary to complete the trial and does not account for the necessary accrual to achieve the intended trial endpoints.

Final patient accrual was obtained from the CTEP-PIO database, with input from the Clinical Data Update System and the Clinical Trials Monitoring Service. Trials that were withdrawn for any reason were excluded (n=1).

Accrual-to-goal percent was computed by dividing the actual trial accrual at trial closure by the projected minimum trial accrual goal. Attainment of the accrual goal was defined as a trial that achieved ≥100% of its projected minimum accrual at trial closure for studies that were completely closed to accrual. Trials were opened for patient accrual at least three years before the evaluation of the trial for accrual performance. Attainment of the accrual goal was more liberally defined for those studies that remained opened to the accrual at the time of trial sampling as those that achieve ≥75% of its projected minimum accrual to account for the possibility of those studies to achieve the intended accrual goal.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Continuous variables were summarized by calculating medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). A maximum 2-tailed alpha of 0.05 was maintained for determining statistical significance. Comparisons among trial types (i.e. phases I,I/II,II,III) were conducted using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Post-hoc comparisons of statistically significant overall tests used Mann-Whitney tests with a Bonferroni-adjusted alpha level of 0.008. Categorical and ordinal groups were summarized using univariate and cross-tabulated frequency distributions. Unadjusted odds ratios were obtained using bivariate logistic regression analysis. To account for the dramatic differences among the sizes of the trials (e.g., phase III tending to be larger than other types of trials, minimum accrual projections were included in multivariate logistic analyses to generate adjusted odds ratios, along with their respective 95% confidence intervals Statistical analyses were performed in either SPSS (version 15.0, descriptive and logistic regression).

RESULTS

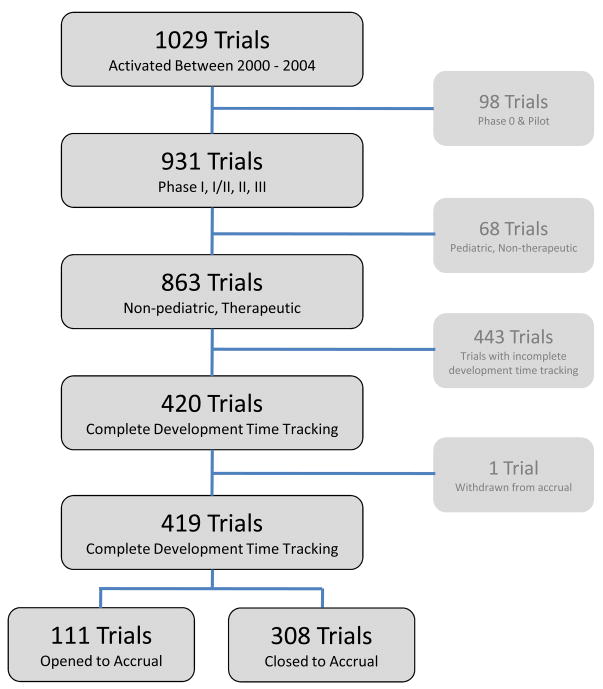

A total of 419 CTEP-sponsored phase I, I/II, II, and III therapeutic, non-pediatric oncology trials that were initiated to patient enrollment within the study period were eligible (Figure 1). Table 1 summarizes the development time and minimal accrual characteristics by phase of trial. Phase II trials accounted for the majority (45.8, 6%, n=192); phase I trials composed 34.1% (n=143), followed by phase III (11.5%, n=48) and phase I/II (8.6%, n=36). Trials with incomplete development time data were excluded (n=443). Incomplete development timing data were observed for reasons including the timing metrics were not being captured in the electronic system (n=72), the concept submission date was not available (n=354), and the activation and concept dates were inconsistent (n=17). The largest exclusion criteria being attributed to the unavailability of the concept date was due to the fact that the clinical trial development process did not include CTEP collaboration during the concept/LOI process; thus, no record was available in the CTEP databases. There was no statistically significant differences in accrual achievement between included and excluded studies were observed (P=0.129).

Figure 1.

Identification of CTEP-Sponsored Clinical Trials Used for the Analysis of Development Time and Accrual Achievement

Table 1.

Summary Statistics for CTEP-Sponsored Phase I, I/II, II, and III Trials

| Phase I (n=143) | Phase I/II (n=36) | Phase II (n=192) | Phase III (n=48) | TOTAL (n=419) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Trial Characteristics | |||||

| Minimum Projected Accrual (median, IQR) | 18 (9–25) | 20 (12.3–35) | 21 (16–34) | 638 (402–1323) | 21 (15–38) |

| Development Time, months (median, IQR) | 13.5 (10.9–18.0) | 13.9 (11.0–17.6) | 13.9 (11.5–17.3) | 17.9 (14.2–23.8) | 14.2 (11.3–18.5) |

| All Trials | 143 | 36 | 192 | 48 | 419 |

| Attainment of Accrual Goal* | 103 (72.0%) | 20 (55.6%) | 123 (64.1%) | 14 (29.2%) | 260 (62.1%) |

| Development Time, months (median, IRQ) | 12.9 (10.5–17.9) | 11.5 (9.0–14.8) | 13.0 (11.1–15.8) | 17.8 (11.7–19.8) | 13.1 (10.9–17.3) |

| Nonattainment of Accrual Goal * | 40 (28.0%) | 16 (44.4%) | 69 (35.9%) | 34 (70.8%) | 159 (37.9%) |

| Development Time, months (median, IRQ) | 15.8 (12.0–20.2) | 14.8 (12.5–18.5) | 15.0 (12.2–19.1) | 18.1 (15.2–26.9) | 15.8 (10.9–17.3) |

| Trials closed to accrual | 98 (68.5%) | 30 (83.3%) | 151(78.6%) | 29 (60.4%) | 308 (73.5%) |

| Attainment of Accrual Goal (no. of Trials with >=100% of accrual goal) | 65 (66.3%) | 16 (53.3%) | 96 (63.6%) | 11 (37.9%) | 188 |

| Nonattainment of Accrual Goal (no. of Trials with <100% of accrual goal) | 33 (33.7%) | 14 (46.7%) | 55 (36.4%) | 18 (62.1%) | 120 |

| Accrual Period, months (median, IQR) | 38 (28–52) | 31 (25–49) | 32 (22–41) | 32 (23–39) | 33 (23–47) |

| Trials open to accrual | 45 (31.5%) | 6 (16.7%) | 41 (21.4%) | 19 (39.6%) | 111 (26.5%) |

| Attainment of Accrual Goal (no. of Trials with >=75% of accrual goal) | 38 (84.4%) | 4 (66.7%) | 27 (65.9%) | 3 (15.8%) | 72 |

| Nonattainment of Accrual Goal (no. of Trials with <75% of accrual goal) | 7 (15.6%) | 2 (33.3%) | 14 (34.1%) | 16 (84.2%) | 39 |

| Accrual Period, months (median, IQR)** | 50 (39–63) | 54 (40–61) | 45 (40–56) | 52 (43–60) | 47 (41–58) |

Success and Failure of a study is defined by the accrual performance of studies closed to accrual and studies that are opened to accrual at time of sampling

Accrual period for studies opened to accrual reflects the time that the study was opened at the time of study sampling. Actual accrual periods may be longer than observed.

Overall median development time from initial CTEP submission to trial activation for all types of trials was 14.2 months (interquartile range (IQR): 11.3–18.5). Phase III trials had statistically longer development time than other types (P<0.008) with a median development time of 17.9 months (IQR: 14.2–23.8). None of the differences in development time between the other types of trials were statistically significant.

Median minimum projected accrual goal for all types of trials was 21 subjects (IQR:15–38) (Table 1). There were significant differences in projected minimum accrual goals between phase I trials compared with phase I/II, phase II, and phase III trials (P<0.008). Additionally, phase III trials had significantly greater projected minimum patient accruals when compared with trials of all other phases (P<0.008).

A total of 308 trials (73.5%) in the cohort were closed to accrual at the time of inspection. Those trials that remained opened to patient enrollment as of 31 January 2007 (n=111, 26.5%), had a median accrual period of 47 months (IQR: 41.4–59.0) with a minimum accrual period of 36.4 months. Phase III trials were the predominate trials that remained opened (n=19, 39.6%) followed by Phase I trials (n=45, 31.5%), Phase II (n=41, 21.4%), and Phase I/II (n=6, 16.7%). There was no statistical difference observed when comparing the attainment of accrual goal across trials that were closed to accrual and those that remained opened (p=0.476).

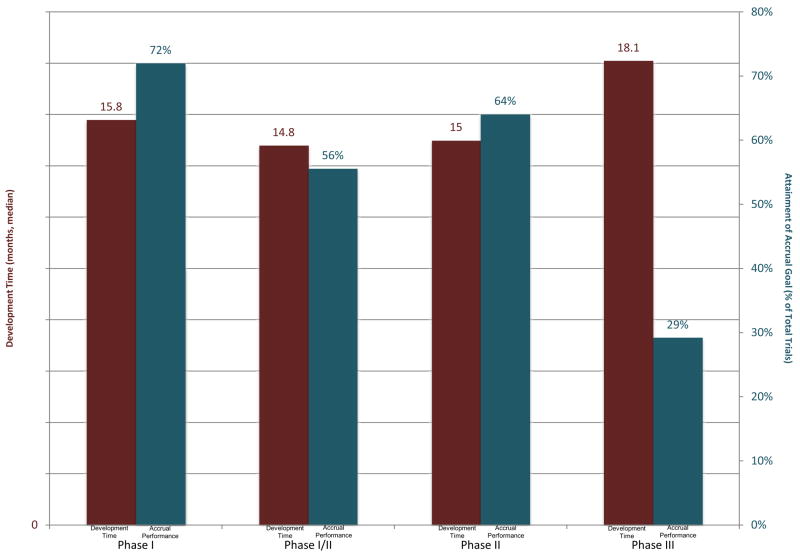

As shown in Table 1, 37.9% (n=221) of all trials did not attain the accrual goal. However, performance of the phase III trials was statistically significantly lower than that of the other types of trials, with 70.8% (n=34) failing to achieve this standard of performance (P<0.001). Particularly problematic in phase III trials, a large number of trials (n=30, 49.2%) failed to achieve 30% of their respective projected minimum accrual goals (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Development Time and Percentage of Total Trials that Attained Accrual Goal by Phase

Phase III development time is significantly greater than phase I, phase I/II, phase II trials (Mann-Whitney test with Bonferroni-adjusted alpha level: p≤0.008). Phase III accrual performance is significantly lower than phase I, phase I/II, phase II trials (Kruskal –Wallis test: p≤0.001)

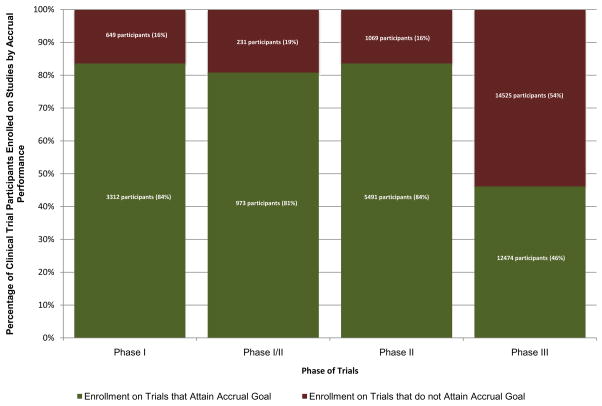

A total of 38724 individuals accrued to the oncology trials in the sample. The majority were enrolled in phase III trials (n=26999, 69.7%), followed by phase II (n=6560, 16.9%), phase I (n=3961, 10.2%), and phase I/II (n=1204, 3.1%). When comparing the proportion of total patients enrolled on trials to patients enrolled on trials that met their projected minimum accrual, it was found that a total of 16474 participants (42.5%, min=16.3% phase II, max=53.8% phase III) were enrolled on clinical trials that closed with underperforming final accruals (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Number (and Percentage) of Clinical Trial Participants Enrolled on Trials that Attained the Accrual Goal vs. Trials that Did Not Attain the Accrual Goal

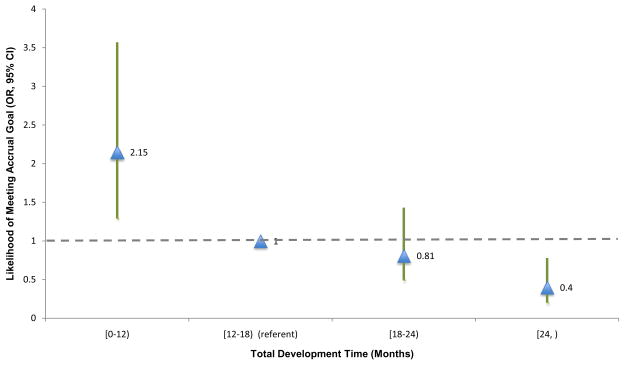

For ease of interpretation, development time was collapsed into 6-month time intervals beginning after 12 months of accrual. Comparisons of the likelihood of attaining the accrual goal were conducted based on the referent category of 12–18 months which was identified by the median development time of the entire sample of 14.2 months. Figure 4 summarizes the likelihoods of achieving minimum accrual goals as the development time varied from the overall median development time.

Figure 4.

Likelihood of Attaining Accrual Goals with Respect to the Development Time for CTEP-Sponsored Trials, 2000–2004

The triangles indicate the the calculated odds ratios with reference to the median development time. The vertical lines represent the 95% confidence intervals. The dotted line indicates the referent as defined by the median development time of the sample.

Relative to trials that fell within the overall median development time, trials consuming less than 12 months of development time from the time of CTEP concept submission were statistically significantly more likely to achieve the minimum accrual goals (OR=2.02; 95% CI,1.21–3.37; P=0.007). On the other hand, trials requiring 24 months or greater of development time were statistically significantly less likely to achieve projected minimum accrual goals than those trials that fell within the overall median development time (OR=0.41; 95% CI, 0.21–0.81; P=0.011). Trials with development times between 18–24 months had a proportionally decreasing likelihood of achieving minimum accrual goals, but the odds ratio was not statistically significant (Table 2).

Table 2.

Unadjusted Odds Ratios for Achieving Minimum Accrual Goals (with Adjusted Values for Projected Minimum Accrual Goals and Type of Trial)

| Development Time Intervals (months) | Unadjusted Analysis | Adjusted Analysis Controlling for Projected Minimum Accrual | Adjusted Analysis Controlling for Trial Phase | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | |

| [0–12) | 2.15 (1.29–3.57) | 0.003 | 2.13 (1.26–3.58) | 0.005 | 2.02 (1.21–3.37) | 0.007 |

| [12–18) (referent) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| [18–24) | 0.81 (0.49–1.43) | 0.469 | 0.87 (0.49–1.57) | 0.65 | 0.83 (0.47–1.48) | 0.535 |

| [24,) | 0.40 (0.20–0.78) | 0.007 | 0.44 (0.22–0.89) | 0.022 | 0.41 (0.21–0.81) | 0.011 |

Grayed row indicates the referent for the analysis

Given the previously established differences in development time of trials of different phases, the likelihood values adjusted for phase of trial were also summarized. Additionally, raw projected minimum accrual numbers tended to be larger with phase III trials. Because these numbers provide a continuous (and thus more powerful) explanatory variable for whether or not accrual goals were met, the development time likelihood values adjusted for raw minimum accrual projections were also displayed. Odds ratios adjusted for raw projected accrual numbers or adjusted for the effect of phase III trials resulted in similar findings when compared to the unadjusted values.

DISCUSSION

This study provides an in-depth analysis of the development time of CTEP-sponsored oncology clinical trials as it impacts trial accrual performance during an eight-year period. The findings demonstrate that the time to bring forth an idea from concept to trial activation has a significant inverse relationship to accrual performance.

The implications of identifying this negative correlation between development time and accrual performance are multiple. First, trials that result in lower than the intended accruals have a limited capacity in statistically supporting the intended scientific objectives necessary to add to the body of scientific knowledge. While early phase trials including phase I and I/II may achieve the scientific endpoint prior to enrolling the necessary accruals, similar finding of low accrual performance was observed across all trials regardless of phase. Particularly importance of this research highlights the low accrual performance for phase III trials where adequate accruals are critical in statistically supporting the underlying scientific objective. Additionally, the scarce resource of patients is being underutilized if patients volunteer for a trial that never achieves its minimum accrual goal.† Data from this research show that almost two out of every five CTEP-sponsored trials will fail to achieve sufficient accruals. For phase III trials, the rate increases to seven failures out of every ten trials conducted. Along the same lines, anywhere between 16% (Phase I, II) to 52% (Phase III) of participants were enrolled on a clinical trial that did not achieve minimum requirements in patient accruals. If we assume that minimum sample size goals were developed using statistical power analysis, failure to achieve such goals results in the limited ability to derive statistically valid conclusions, therefore resulting in a less significant advancement of science than originally intended.

Explanation for the observation in the inverse relationship between long clinical trial development time and poor accrual performance are numerous. The field of oncology clinical research evolves quickly, which may cause interest in the original research question to wane as development time is prolonged.13 Alternatively, long development times as well as poor accruals may be due to a lack of interest in the clinical trial from the origination of the idea. Should trials be allowed to begin enrolling patients if scientific interest has waned or the underlying scientific interest is not of importance? Regardless, pursuing clinical trials with a reduced likelihood of attaining the accrual goal limits the opportunity to conduct other clinical trials.

In an era of clinical research where material resources limit the number of trials that can be pursued, as well as the limited availability of individuals willing to participate in clinical trials, it is essential to identify potential causes of low accrual likelihood before allocating significant resources to develop such trials. The retrospective analyses of phase I, I/II, II, and III trials suggest that there are opportunities to improve the number of trails that attain the accrual goal. In particular, phase III clinical trial development times should be improved not only because of the potential importance of the findings of phase III trials on current standard of care, but also because such trials are the most resource-consuming in terms of time, effort, and patient accruals. In our analysis, we found that phase III trials both had the greatest amount of development time, the highest number of trials that did not achieve the accrual goals, and had the largest number of patients enrolled on studies that did not achieve necessary accruals.

Clinical trial development time is complicated by the many facets of scientific study design within the constraints of regulatory, ethical, and operational requirements.14 Research delays during the development of a clinical trial can often be attributed to the improvement of overall scientific merit or to efforts meant to ensure safety of the potential participants. However, opportunities to improve development time arise when considering the number of non-value added (NVA) steps in the process flow, as well as the number of multiple, redundant, and/or overlapping steps involved in opening clinical trials.10, 15 Findings from this research indicate that any decisions beyond the scope of scientific relevancy or ethical issues that delay the deployment of clinical trials have negative repercussions on the likelihood of attaining the accrual goal.

Finally, why is longer development time of interest beyond its negative effects on the likelihood of attaining accrual goal? There are two other reasons: 1) patients will gain access to new therapies later than they otherwise would (if ever) and 2) longer development times create reduced innovation incentives as researchers concentrate on completing studies that have lower minimum patient accrual goals, which may result in fewer new therapies being developed. It is imperative that the systems and processes for clinical trial development be created to foster better and faster clinical trial development, with a minimum of administrative barriers. As noted in this study, a large number of trials (n=419) were observed to have incomplete development tracking data of studies. Utilizing predictors and metrics during the development stage of the clinical trial is critical not only as a method to track the progress of trials, but findings from this research suggest that it can be used to examine potential accrual performance prior to first enrollment. This poses the additional question regarding ethical implications of enrolling patients on studies with diminished likelihood of achieving the ultimate accruals necessary to support the underlying scientific objective: Have studies that have failed to complete the intended accrual breached an ethical contract with the participants; and moreover; should accrual and study results be disclosed to them?

A limitation of this analysis is that only the development time variable has been analyzed with regard to successful accrual. While there is a host of other reasons for low accruals, this research demonstrates that one previously overlooked but important barrier to accrual—development time—should be included in any investigation of low accrual causes. Continued research to uncover additional barriers within pre-activation efforts is imperative in order to foster the rapid access of clinical trials to patients and to improve the likelihood of achieving the desired clinical trial objective.

TRANSLATIONAL RELEVENCE.

The development of clinical trials has been shown to be a long and arduous process. Furthermore, obtaining adequate accruals to oncology clinical trials is a major and persistent problem. The present study uncovers the relationship of long development times on accrual performance. The implications of the findings highlight the importance to reduce all unnecessary delays; overcoming barriers to development time have implications to improving accruals to trials. The field of oncology evolves quickly rendering original research questions obsolete if not implemented in a timely manner. Therefore, continued efforts to uncover additional barriers to development time are a critical component to translating scientific knowledge to improved therapeutic options.

Acknowledgments

Supported by Grant No. 3U10 CA 21115-32 from the National Cancer Institute to Comis, RL and by subcontract to Dilts, DM and Sandler, AB

Footnotes

The authors indicate no potential conflicts of interest

Presented in part at the 2008 Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Orlando, FL, May 29 –June 2, 2009

We acknowledge that many clinical trials closed due to adverse events both related to the clinical trial itself as well as derived from other similar study. Unfortunately we do not have the rational for study closing for the sample.

References

- 1.SEER cancer statistics review. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heron M, Hoyert D, Xu J, Scott C, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: Preliminary data for 2006. National vital statistics reports. 2008;56:1–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials: race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. Jama. 2004;291:2720–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petrelli NJ, Grubbs S, Price K. Clinical trial investigator status: you need to earn it. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2440–1. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.5050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Go RS, Frisby KA, Lee JA, et al. Clinical trial accrual among new cancer patients at a community-based cancer center. Cancer. 2006;106:426–33. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lara P, Jr, Higdon R, Lim N, et al. Prospective evaluation of cancer clinical trial accrual patterns: identifying potential barriers to enrollment. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2001;19:1728. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.6.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mills EJ, Seely D, Rachlis B, et al. Barriers to participation in clinical trials of cancer: a meta-analysis and systematic review of patient-reported factors. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:141–8. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70576-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dilts DM, Sandler AB, Cheng SK, et al. Steps and time to process clinical trials at the Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1761–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.9133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dilts DM, Sandler A, Cheng S, et al. Development of clinical trials in a cooperative group setting: the eastern cooperative oncology group. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3427–33. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dilts DM, Sandler AB, Baker M, et al. Processes to activate phase III clinical trials in a Cooperative Oncology Group: the Case of Cancer and Leukemia Group B. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4553–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.7819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wheelwright SC, Clark KB. Revolutionizing product development: quantum leaps in speed, efficiency, and quality. New York Toronto: Free Press; Maxwell Macmillan Canada; Maxwell Macmillan International; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ansher S, Scharf R. The Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program (CTEP) at the National Cancer Institute. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;949:333–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb04041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lara PN, Jr, Higdon R, Lim N, et al. Prospective Evaluation of Cancer Clinical Trial Accrual Patterns: Identifying Potential Barriers to Enrollment. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2001;19:1728. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.6.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zerhouni EA. Translational and clinical science--time for a new vision. The New England journal of medicine. 2005;353:1621–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb053723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dilts DM, Sandler AB. Invisible barriers to clinical trials: the impact of structural, infrastructural, and procedural barriers to opening oncology clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4545–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]