Abstract

The Drosophila CNS contains a variety of glia, including highly specialized glia that reside at the CNS midline and functionally resemble the midline floor plate glia of the vertebrate spinal cord. Both insect and vertebrate midline glia play important roles in ensheathing axons that cross the midline and secreting signals that control a variety of developmental processes. The Drosophila midline glia consist of two spatially and functionally distinct populations. The anterior midline glia (AMG) are ensheathing glia that migrate, surround and send processes into the axon commissures. By contrast, the posterior midline glia (PMG) are non-ensheathing glia. Together, the Notch and hedgehog signaling pathways generate AMG and PMG from midline neural precursors. Notch signaling is required for midline glial formation and for transcription of a core set of midline glial-expressed genes. The Hedgehog morphogen is secreted from ectodermal cells adjacent to the CNS midline and directs a subset of midline glia to become PMG. Two transcription factor genes, runt and engrailed, play important roles in AMG and PMG development. The runt gene is expressed in AMG, represses engrailed and maintains AMG gene expression. The engrailed gene is expressed in PMG, represses runt and maintains PMG gene expression. In addition, engrailed can direct midline glia to a PMG-like non-ensheathing fate. Thus, two signaling pathways and runt-engrailed mutual repression initiate and maintain two distinct populations of midline glia that differ functionally in gene expression, glial migration, axon ensheathment, process extension and patterns of apoptosis.

Keywords: CNS midline, Drosophila, Engrailed, Glia, Hedgehog, Runt

INTRODUCTION

Diverse glial cell types populate the CNS. Different kinds of glia can ensheath axons, support neuronal function, act as phagocytes and constitute a blood-brain barrier. Even closely related glial cell types have different functions. For example, vertebrate Schwann cells can develop into two distinct populations: those that myelinate axons and those that are non-myelinating (Mirsky et al., 2008). Drosophila possess a set of glia that reside at the midline of the ventral nerve cord. These midline glia (MG) play multiple roles in development, including: (1) ensheathing commissural axons, (2) directing axon guidance and muscle cell migration, and (3) controlling formation of several embryonic cell types via cell signaling pathways (Crews, 2003). Similarly, the vertebrate spinal cord and brain have a specialized set of glial-like midline cells, the floor plate, that also ensheath commissural axons and use cell signaling proteins to direct axon guidance and pattern the spinal cord (Campbell and Peterson, 1993; Yoshioka and Tanaka, 1989). Although relatively little is known regarding how floor plate cells ensheath and interact with crossing axons, the Drosophila MG have been well-characterized, both at the cellular and molecular levels. In Drosophila, the MG also exist as two functionally distinct populations, anterior MG (AMG) and posterior MG (PMG), which have different gene expression, migratory and ensheathment properties (Dong and Jacobs, 1997; Kearney et al., 2004). Given the increasing awareness of the significance of glia to CNS function (Allen and Barres, 2009), it is important to understand how diverse glial cell types are generated. In this paper, we describe the regulatory mechanisms that establish AMG and PMG cell fates, how those differences are maintained and how they impact MG function.

The Drosophila CNS midline cells are an outstanding system to study how glia and neurons acquire their identities. The midline cells, although small in number (22 cells per segment at the end of embryogenesis), nevertheless comprise motorneurons, interneurons, neurosecretory cells and two types of MG (AMG and PMG) (Wheeler et al., 2006). Midline neurons are derived from the median neuroblast (MNB) and five midline precursors (MPs) named MP1 and MP3-6. During stage 10, the 16 midline cells are arranged in three equivalence groups consisting of four to six MPs each: the MP1, MP3 and MP4 groups (the MP4 group gives rise to MP4-6 and the MNB). From these equivalence groups, Notch signaling directs the formation of MG (Menne and Klämbt, 1994; Wheeler et al., 2008). After MG formation, the differences in AMG and PMG become apparent; these include position, function, cell survival and differential gene expression (Fig. 1A). AMG arise in the anterior part of the segment and express high levels of wrapper, which encodes an immunoglobulin domain-containing GPI-linked membrane protein involved in MG-axonal adhesion (Noordermeer et al., 1998). During stage 12, AMG move internally (Fig. 1A,B) to contact commissural axons and those that are not in close proximity to the commissures undergo apoptosis (Bergmann et al., 2002). The surviving AMG then migrate posteriorly to ensheath the two axon commissures in a stepwise fashion: first the anterior commissure (AC) at stages 13-15 (Fig. 1A,C,D) and then the posterior commissure (PC) at stages 16-17 [for a more detailed discussion, see Wheeler et al. (Wheeler et al., 2009)]. One aspect of ensheathment is the further subdivision of the commissures by glial projections (Stollewerk and Klämbt, 1997; Stork et al., 2009; Wheeler et al., 2009). These MG projections might enhance neuronal survival by increasing MG secretion of neurotrophins onto commissural axons (Zhu et al., 2008), and might also enhance MG survival by increased exposure to the axonal-derived spitz survival signal (Bergmann et al., 2002). In contrast to AMG, PMG arise in the posterior of the segment and express low levels of wrapper (Wheeler et al., 2006; Wheeler et al., 2008). PMG move internally (Fig. 1A,B; stage 12) and from stages 13-17 they abut the posterior commissure, but do not ensheath or extend projections (Fig. 1C,D). The function of PMG is unknown and all PMG undergo apoptosis by mid-stage 17 (Dong and Jacobs, 1997; Sonnenfeld and Jacobs, 1995).

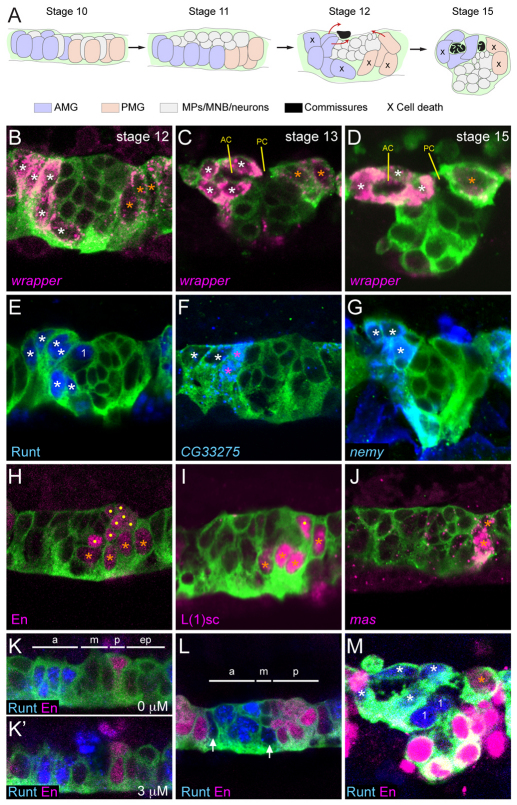

Fig. 1.

Anterior midline glia (AMG) and posterior midline glia (PMG) differ in gene expression and origins. (A) Schematic summary of midline glia (MG) positioning and migration in sagittal views. The schematic depicts an idealized view; actual segments vary in MG number and position. Colored objects represent nuclei, and pathways of AMG and PMG migration are indicated at stage 12 by red arrows. MNB, median neuroblast; MP, midline precursor. (B-M) Fluorescence confocal images of single segments in sagittal view from sim-Gal4 UAS-tau-GFP embryos. Anterior is to the left and dorsal (internal) is up. White asterisks indicate AMG; orange asterisks, PMG; dots, midline neurons; ‘1’, MP1 neurons. RNA (italicized) and antibody (non-italicized) stains and corresponding colors are indicated in the lower left corner of each panel except for anti-GFP staining (green) that is present in all images. (B) During stage 12, AMG (high levels of wrapper RNA) and PMG (low levels of wrapper RNA) are elongating and moving to the dorsal (internal-most) surface of the CNS. Midline neurons are the centrally located wrapper− cells flanked by wrapper+ MG. (C) During stage 13, AMG migrate posteriorly above and below the anterior commissure (AC). PMG abut the posterior commissure (PC). (D) By stage 15, AMG completely surround the AC and are poised to ensheath the PC. Most PMG have undergone apoptosis; the remainder stay in contact with the PC. (E-G) Runt is present in all AMG and the MP1 neurons, whereas CG33275 and nemy expression is restricted to AMG only. The AMG closest to the midline neurons and developing commissure (pink asterisks) have high levels of CG33275, compared with those that are more distant (white asterisks). (H-J) En and L(1)sc are present in all PMG and in a subset of midline neurons whereas mas is expressed in only one or two PMG in each segment. (K,K′) Two focal planes (separated by 3 μm) of a stage 10 segment; Runt is present in four to five cells in the anterior cells (a), Runt and En are absent from the middle (m) and extreme posterior cells (ep), and En is present in two cells in the posterior (p). (L) During stages 10-11, Runt expands to additional MG (arrows) and the number of En+ cells increases (stage 11 is shown). The segment is divided into anterior (a) runt+ en−, middle (m) runt− en− and posterior (p) runt− en+ domains. (M) In stage 15 MG, Runt and En are present in AMG and PMG, respectively.

Mechanistic insight into MG migration and ensheathment emerged from studies showing that the Wrapper protein is a heterophilic cell adhesion molecule present on MG that interacts with the Neurexin IV (Nrx-IV) transmembrane protein present on the surface of neuronal axons and cell bodies (Noordermeer et al., 1998; Stork et al., 2009; Wheeler et al., 2009). Genetic studies demonstrated that MG migration and ensheathment require both Nrx-IV and wrapper. Thus, the ability of AMG, and the corresponding inability of PMG, to migrate along and ensheath axons might be due, in part, to the levels of Wrapper present on their surfaces. Given the importance of differences between AMG and PMG, we sought to understand the developmental and genetic basis of their divergent characteristics.

In this paper, we explore the differentiation of AMG and PMG. We demonstrate that Hedgehog (Hh), secreted from cells adjacent to the midline, directs MG in the posterior of the segment to become PMG. By contrast, MG in the anterior of the segment do not respond to Hh and become AMG. Hh functions both by repressing AMG gene expression and activating PMG gene expression. One of the targets of Hh in PMG is the engrailed (en) gene, which encodes a homeodomain protein. AMG gene expression is repressed by en in PMG, and en also directs MG, in part, to function as PMG. The RUNX-family transcription factor Runt is present in AMG, but not PMG. runt is required for AMG gene expression, functions by repressing en in AMG, and is required for the expression of at least one AMG-specific gene. Similarly, en represses runt in PMG. Thus, two transcriptional repressors, En and Runt, are partitioned into different populations of MG, and are key regulators in directing cell type-specific gene expression and function. This includes regulating levels of wrapper in MG that might lead to functional differences in MG migration and axon ensheathment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila strains

Drosophila mutant strains used included: Df(2R)enE (Gustavson et al., 1996), Df(2R)en-A (Gubb, 1985), hhAC (Lee et al., 1992), hh2 (Nusslein-Volhard and Wieschaus, 1980), runt3 (Gergen and Wieschaus, 1986), runt29 (Wieschaus et al., 1984) and Df(1)sc-B57 (Jimenez and Campos-Ortega, 1990). Gal4 and UAS lines employed were: sim-Gal4 (Xiao et al., 1996), UAS-ci.VP16 (Larsen et al., 2003), UAS-en (Guillen et al., 1995), UAS-VP16En (Alexandre and Vincent, 2003), UAS-hh (Porter et al., 1996), UAS-runtU15 (Tracey et al., 2000) and UAS-tau-GFP (Brand, 1995).

In situ hybridization, immunostaining and microscopy

Embryo collection, in situ hybridization and immunostaining were performed as previously described (Kearney et al., 2004). Digoxygenin-labeled antisense RNA probes for in situ hybridization were generated from either: (1) cDNA clones from the Drosophila Gene Collection (Open Biosystems, AL, USA) (CG33275: GM01778; Fhos: LD24110; mas: LP06006; and wrapper: GH03113) or (2) genomic DNA PCR-amplified using gene specific primers (hh, nemy and ptc). Primary antibodies used were: mouse MAb BP102 [Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB)], mouse and rat MAb anti-Elav (DSHB), mouse MAb anti-En (Patel et al., 1989), rabbit anti-GFP (Ab290, Abcam), guinea pig and rat anti-L(1)sc (S.B.S., unpublished), rabbit anti-Nrx-IV (Baumgartner et al., 1996), guinea pig anti-Runt (Kosman et al., 1998), mouse anti-Tau (Tau-2, Sigma) and mouse anti-Wrapper MAb 10D3 (DSHB) (Noordermeer et al., 1998). Secondary antibodies used were conjugated with AlexaFluor 488, 543, 568 and 647 (Invitrogen). Stained embryos were imaged on Zeiss LSM-PASCAL, LSM-510 and LSM-710 confocal microscopes. All images are from abdominal segments and are single optical planes derived from z-series stacks or single cuts taken from stacks that were rotated using the Zen 2008 software (Zeiss).

RESULTS

Differential gene expression of AMG and PMG

Insights into the functional differences between AMG and PMG can arise from identifying genes differentially expressed in AMG and PMG. In a previous in situ hybridization screen, we identified 54 genes expressed in MG (Kearney et al., 2004; Wheeler et al., 2006). Using fluorescence in situ hybridization and confocal microscopy, we analyzed the expression patterns of eight MG-expressed genes in the sim-Gal4 UAS-tau-GFP genetic background, in which the position and morphology of midline cells can be visualized. Each gene was differentially expressed in AMG and PMG during stage 12, a time when AMG-PMG differences are readily observed (Table 1). wrapper was expressed at high levels in AMG and at low levels in PMG (Fig. 1B-D). The genes runt, CG33275, no extended memory (nemy) and Fhos (Fig. 1E-G; not shown) were expressed in AMG, and en, lethal of scute [l(1)sc] and masquerade (mas) (Fig. 1H-J) were expressed in PMG. Whereas runt, nemy and Fhos were expressed at comparable levels in all AMG, CG33275 was expressed at high levels in a subset of AMG (Fig. 1F). Similarly, en and l(1)sc were expressed at comparable levels in all PMG, whereas mas was expressed in only one to two PMG (Fig. 1J). The high level of expression of CG33275 in a subset of AMG, and expression of mas in a subset of PMG indicate that both AMG and PMG might also possess functionally distinct subtypes.

Table 1.

Genes differentially expressed in anterior midline glia (AMG) and posterior midline glia (PMG)

runt and en expression defines distinct midline domains

Prior to stage 10, both runt and en are expressed in pair-rule and segment polarity patterns in the ectoderm, including the corresponding midline cells (Bossing and Brand, 2006; Wheeler et al., 2006). During stages 10 and 11, the expression patterns of both runt and en change, becoming more expansive. At stage 10, runt was present in four to five midline cells and en in two midline cells (Fig. 1K,K′). These patterns are referred to as ‘early runt’ and ‘early en’ and they subdivide the midline into four regions: anterior (runt+ en−), middle (runt− en−), posterior (runt− en+) and extreme posterior (runt− en−) (Fig. 1K,K′). Owing to Notch signaling, the MP1 and approximately four AMG arise from the runt+ en− region, and the MP3 and additional MG arise from the middle runt− en− region (Wheeler et al., 2008). At stage 11, an additional, late phase of runt expression was initiated in two to three additional cells flanking the runt+ en− region (Fig. 1L). This includes the MG from the middle runt− en− region, thus generating about six runt+ AMG in the anterior of each segment. A second, late phase of en expression was activated in the extreme posterior runt− en− cells that, in combination with the early en+ cells, generated a single posterior en+ region containing around eight cells (Fig. 1L). These en+ cells give rise to PMG, MP4-6 and the MNB (Wheeler et al., 2008). Thus, by the end of stage 11, runt expression was present in all AMG and en expression was present in all PMG; this pattern of MG gene expression persisted throughout embryonic development with no overlap in expression (Fig. 1M).

hh signaling is a key regulator of midline glial cell fate

AMG and PMG reside at different positions along the anterior/posterior (A/P) axis, suggesting that segmentation genes direct their formation. Previous work indicated that hh function is required for late en expression in the posterior midline cells (Bossing and Brand, 2006), and we addressed whether hh is controlling aspects of PMG development. The patched (ptc) gene encodes a receptor for Hh, and the presence of ptc expression is an indication that a cell can respond to Hh signaling (Chen and Struhl, 1996). In situ hybridization with a ptc probe revealed ptc expression at stage 10 in most midline cells, with the early en+ cells being an exception (Fig. 2A,B,D). As late en levels increased in posterior cells, ptc expression was reduced (Fig. 2B,C). This is likely to be due to the ability of en to repress ptc expression (Hidalgo and Ingham, 1990). At this time, hh was expressed in ectodermal stripes, but only at very low levels in midline cells (Fig. 2E). Thus, most midline cells were initially ptc+ and able to respond to hh signaling [as also noted by Bossing and Brand (Bossing and Brand, 2006)], and any hh signaling affecting the midline cells at stage 10 probably originates from cells adjacent to the midline.

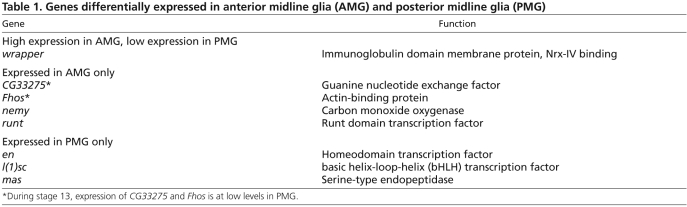

Fig. 2.

hh activates en and represses runt expression. (A-G) Sagittal (A-C′,F,G) or horizontal (D,E) views of stage 10 sim-Gal4 UAS-tau-GFP embryos. (A,A′) Initially, En is present in two cells in each segment (arrows; referred to as early en) that do not express ptc. Expression of ptc is present in all other midline cells. (B,B′) Later, the En+ ptc− cells (arrow) elongate and En appears in cells just to the posterior (white arrowheads). The flattened En− MP4 (yellow arrowhead) has delaminated and resides internally and immediately posterior to the early en+ cells. (C,C′) At the end of stage 10, about eight cells are En+ (white arrowheads) and ptc is decreasing in these cells. Not all cells are shown in this focal plane. Expression of en is activated in the MP4 prior (yellow arrowheads) to its division. The tau-dense appearance of MP4 is indicative of cell division (Wheeler et al., 2008). (D) ptc is expressed in the midline cells flanking the early En+ cells (arrowheads). (E) During stage 10, hh and En colocalize in stripes in the non-midline ectoderm; hh is nearly absent in the midline cells. Yellow dots indicate En+ midline cells. (F) In hh mutant embryos, two En+ cells are present (arrows), but En is absent from posterior cells. (G) Runt is expanded to all but two cells (arrows) in each segment in stage 10 hh mutants.

The effects of hh signaling on en and runt MG expression were assessed in both hhAC homozygous null and hhAC/hh2 mutant embryos and the phenotypes were the same. At late stage 10-early stage 11, only two en+ cells were present (Fig. 2F), instead of eight en+ cells in wild type (Fig. 1L, Fig. 2C′). These are likely to be the early en+ cells: they lined up with the en CNS stripe in both wild-type and hh mutant embryos, and in wild-type embryos, the early en+ cells were ptc− and thus unable to respond to hh signaling. By contrast, runt was expanded in all midline cells, except for two cells (Fig. 2G). The presence of en and runt was further examined in stage 12 hhAC mutant embryos: en was absent from all MG, as identified by wrapper staining (Fig. 3A,B), and runt was present in all MG (Fig. 3D,E). These results indicate a requirement for hh in activating en and repressing runt expression in PMG.

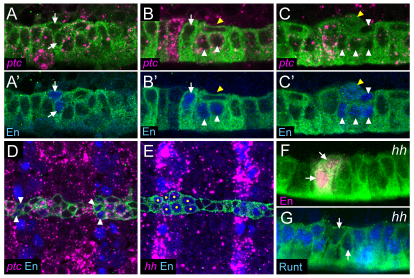

Fig. 3.

hh regulates anterior midline glia (AMG) and posterior midline glia (PMG) gene expression. Sagittal views of stage 12 segments with genotypes listed above each column. (A,A′) In wild type, En is present in the low wrapper+ PMG (orange asterisks) and a subset of wrapper− midline neurons (dots). (B,B′) In the absence of hh, En is absent from all MG, and all MG are high wrapper. (C,C′) In hh misexpression embryos, all MG are En+ and low wrapper. Midline neurons, which are smaller than MG, are the centrally located wrapper− cells. (D,D′) In wild type, Runt is present in the high wrapper+ AMG (white asterisks) and the MP1 (midline precursor 1) neurons (1); the second MP1 neuron is out of the plane of focus. (E,E′) In hh mutants, all MG are Runt+ and high wrapper+. Four neurons are present in each segment (dots), two are Runt+ (magenta dot; the other neuron is out of the plane of focus). (F,F′) hh misexpression results in a complete absence of Runt+ MG, but does not affect Runt in MP1 neurons (1). (G-I) The AMG expression of nemy expands to all MG in the absence of hh, and is absent when hh is misexpressed in all midline cells. White asterisks indicate AMG and yellow dots indicate neurons. (J-L) mas is expressed in one or two PMG per segment in wild type; expression is absent in hh mutant embryos, and increases slightly in hh misexpression embryos. (M,N) Misexpression of UAS-ci.VP16 using sim-Gal4 results in MG that are En+ and Runt−.

Owing to the pleiotropy of hh mutants, misexpression experiments provide a more direct test than mutants of the ability of hh signaling to influence MG gene expression. Embryos that are sim-Gal4 UAS-hh express hh in all midline cells and were assayed for en and runt expression. The results showed a phenotype opposite to hh mutants: en was present in all MG (Fig. 3C) and runt was absent (Fig. 3F). To test whether changes in midline runt and en expression are produced by a secondary effect of hh misexpression on non-midline cells, we used sim-Gal4 to misexpress UAS-ci.VP16, a constitutively activating form of the Hh-responsive Cubitus Interruptus (Ci) transcription factor (Fig. 3M,N). This resulted in a phenotype similar to sim-Gal4 UAS-hh (en was present in all MG and runt was absent from MG) indicating that hh signaling can directly influence PMG gene expression. Analysis of additional differentially expressed genes demonstrated further that hh controls PMG gene expression. In wild-type embryos, wrapper levels were high in AMG and low in PMG (Fig. 3A′,D′), nemy was present in AMG and absent from PMG (Fig. 3G), and mas was expressed in a subset of PMG (Fig. 3J). In hh mutants, all MG had high levels of wrapper (Fig. 3B′,E′) and nemy (Fig. 3H), but mas was absent (Fig. 3K). By contrast, sim-Gal4 UAS-hh embryos had low-levels of wrapper (Fig. 3C′,F′), nemy was absent (Fig. 3I) and the number of mas+ cells increased slightly to 2.5 per segment (n=10 segments) (Fig. 3L) from a wild-type average of 2.1 per segment (n=14 segments). Unlike en, mas expression did not expand into AMG. Similar to the wrapper and nemy results, the AMG-expressed genes CG33275 and Fhos showed identical results in hh mutant and misexpression embryos (not shown). Together, these experiments indicate that hh signaling is required for PMG gene expression (en, mas, low wrapper) and for repressing AMG gene expression (CG33275, Fhos, nemy, runt, high wrapper).

runt and en control differential midline glial gene expression

The hh gene partitions runt and en into different MG compartments, but do runt and en influence MG development and transcription? This was addressed in misexpression and loss-of-function experiments with both genes. When sim-Gal4 UAS-runt embryos were analyzed for MG gene expression, AMG gene expression was observed in all MG, including high levels of wrapper (Fig. 4A,E), nemy (Fig. 4B,F), CG33275 (Fig. 4C,G) and Fhos (not shown) expression. Concomitantly, there was a reduction in PMG gene expression, including a strong reduction in the number of mas-expressing cells (0.3 cells per segment; n=12) (Fig. 4D,H). Analysis of runt mutants is complicated because of the gap and pair-rule functions of runt, which lead to differences in ectodermal patterning along the A/P axis (Tsai and Gergen, 1994). Thus, in addition to being runt−, some segments in the anterior of the embryo had expanded hh and en expression, and some posterior segments were devoid of en and hh expression (Fig. 5G,H) (Jaynes and Fujioka, 2004). In anterior segments of both runt3 and runt29 mutants, which were runt− en+, we observed that MG gene expression was PMG-like, the opposite result to runt misexpression. Levels of wrapper were low (Fig. 4I) and expression of nemy and CG33275 was absent in many segments (Fig. 4J,K). Identifying distinct segments was difficult in runt mutants, but mas expression was present in repeated clusters of cells that might correspond to individual segments (Fig. 4L). The number of mas+ cells in each cluster (5.5 cells per segment; n=15), was higher than in wild type (2.1 cells per segment). Thus, the runt mutant and misexpression data were both consistent with runt repressing PMG gene expression.

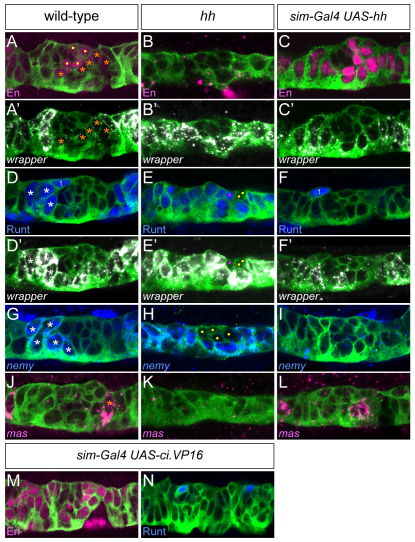

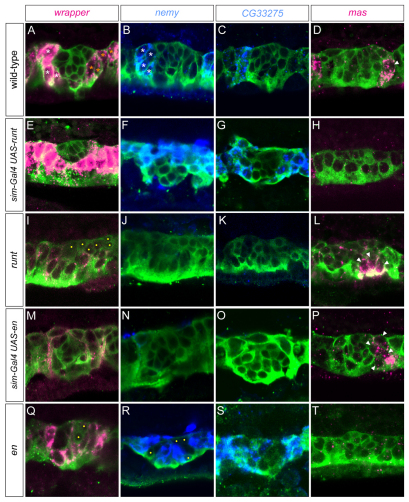

Fig. 4.

runt and en control midline glia (MG) subtype-specific gene expression. Sagittal views of stage 12 segments. Dots denote wrapper− midline neurons in mutant embryos. (A-D) In wild-type embryos, wrapper is expressed at high levels in anterior midline glia (AMG; white asterisks) and low levels in posterior midline glia (PMG; orange asterisks); nemy and CG33275 are expressed in AMG only; and mas (arrowhead) is expressed in PMG only. (E-H) runt misexpression results in MG that express high wrapper, nemy and CG33275, whereas mas expression is absent. (I-L) In anterior regions of runt mutant embryos (yellow bar in Fig. 5H,H′ indicating runt− en+ cells), wrapper is expressed at low levels in all MG (yellow dots indicate midline neurons), nemy and CG33275 expression are absent, and the number of mas+ cells is increased (arrowheads). (M-P) Misexpression of en results in low levels of wrapper, absence of nemy and CG33275 expression, and a slight increase in the number of mas+ cells (arrowheads). (Q-T) en mutants have high levels of wrapper, nemy and CG33275 in MG, whereas mas expression is absent. Yellow dots indicate neurons.

Fig. 5.

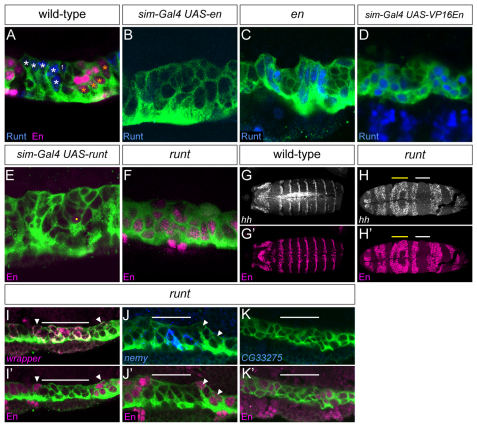

runt and en mutually repress. (A-K′) Sagittal (A-F,I-K) and horizontal (G-H′) views of stage 12 segments. (A) In wild type, Runt is present in the anterior midline glia (AMG; white asterisks) and midline precursor 1 (MP1) neurons (1), whereas En is present in posterior midline glia (PMG; orange asterisks) and a subset of midline neurons. (B) Misexpression of en in all midline cells results in a complete absence of Runt. (C) In en mutant embryos, Runt is present in all midline glia (MG). (D) Misexpression of a constitutively activating form of en (UAS-VP16En) results in the presence of Runt in all MG. (E) runt misexpression results in the absence of En+ MG. Yellow dot indicates an En+ neuron. (F) In anterior regions of runt mutant embryos (yellow bar in H,H′), En is present in all MG. (G,G′) In wild-type embryos, hh and En are present in collinear segmentally repeated ectodermal stripes. (H,H′) In runt mutant embryos, the regular pattern of hh and En stripes is disrupted, with anterior regions of expanded hh and En (yellow bars), and posterior regions devoid of hh and en (white bars). (I-K′) MG gene expression was analyzed in posterior regions of runt mutant embryos that are runt− en− (white bar in H,H′). (I-J′) wrapper and nemy levels are high in runt− en− MG (below white bar), but low or absent in adjacent runt− en+ regions (arrowheads). (K,K′) By contrast, CG33275 is absent in runt− en− regions.

Analysis of sim-Gal4 UAS-en embryos revealed a PMG-like pattern of gene expression, a phenotype similar to hh misexpression: wrapper (Fig. 4M) levels were reduced, and nemy (Fig. 4N), CG33275 (Fig. 4O) and Fhos (not shown) expression was absent. The number of mas+ cells was increased (3.0 cells per segment; n=20) (Fig. 4P). The opposite results were observed in en null mutant embryos (Df(2R)EnE/Df(2R)En-A); wrapper (Fig. 4Q), nemy (Fig. 4R), CG33275 (Fig. 4S) and Fhos (not shown) expression was high in all MG and mas expression was absent (Fig. 4T). Although the MG phenotypes of en mutants were opposite to (and thus consistent with) the en misexpression phenotypes, en was required for hh expression in the ectoderm (Lee et al., 1992). Consequently, the en mutant phenotype cannot be unambiguously attributed solely to loss of en function. The more convincing evidence was produced by the misexpression experiments, because they demonstrate that midline-expressed runt and en can directly influence MG gene expression. Together, these experiments indicate that en represses AMG gene expression and that runt represses PMG gene expression.

Mutual repression between en and runt

Because runt represses PMG gene expression and en represses AMG gene expression, we addressed whether they mutually repress each other. Misexpression of en in sim-Gal4 UAS-en embryos resulted in the absence of MG runt expression (Fig. 5A,B). Similarly, runt expression expanded to all MG in en mutant embryos (Fig. 5C). Thus, en represses runt in PMG. Misexpression of a version of en with an activation domain (UAS-VP16En) (Alexandre and Vincent, 2003) resulted in the appearance of runt in all MG (Fig. 5D). This indicates that en normally functions biochemically as a repressor in runt repression, rather than activating a runt repressor. Misexpression of runt in sim-Gal4 UAS-runt embryos resulted in an absence of en in MG (Fig. 5E), and en expanded to additional MG in anterior regions of runt mutant embryos (Fig. 5F). These results indicate that runt represses en in AMG. Thus, these data demonstrate runt and en mutual repression, and this repression probably ensures the maintenance of AMG and PMG patterns of gene expression.

The runt gene represses en and PMG gene expression in AMG, but is it required for AMG gene expression? This issue was addressed by examining gene expression in MG devoid of both en and runt, thus allowing the role of runt to be assessed in the absence of the repressive role of en on AMG gene expression. In the posterior regions of runt mutants, expanded ectodermal expression of sloppy paired 1 (slp1) leads to repression of en (Jaynes and Fujioka, 2004) creating regions that are devoid of both en and runt (Fig. 5G,H). These runt− en− regions had high levels of wrapper (Fig. 4I, Fig. 5I,I′), nemy (Fig. 4J, Fig. 5J,J′) and Fhos (not shown). However, expression of CG33275 was absent (Fig. 4K, Fig. 5K,K′). By contrast, the flanking runt− en+ regions had low wrapper expression (Fig. 5I,I′) and no nemy (Fig. 5J,J′), Fhos (data not shown) or CG33275 (Fig. 5K,K′) expression. As AMG gene expression is present in runt− en− MG, the major function of runt might be to repress en and PMG gene expression in AMG. However, the absence of expression of at least one gene (CG33275) in runt− en− regions indicates that runt can also positively influence AMG gene expression.

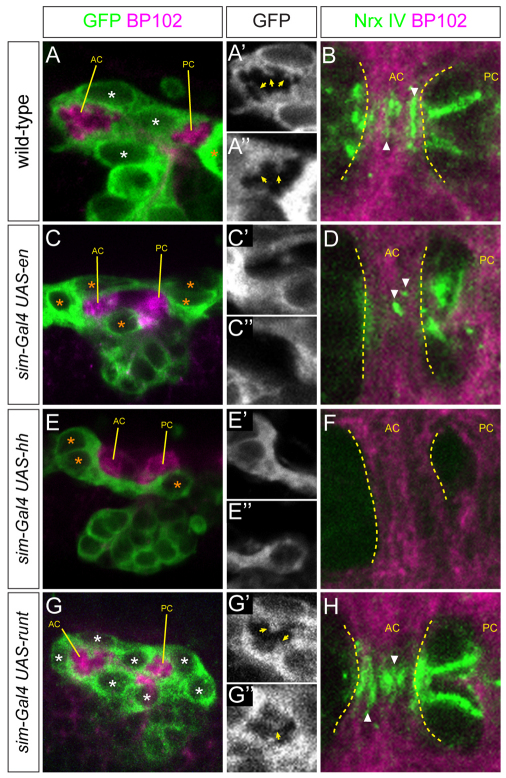

en contributes to PMG cell fate

Analysis of gene expression by en misexpression experiments indicates that en normally represses runt and AMG gene expression in PMG. Because en mutant embryos also affect hh signaling, it is difficult to examine the functional role of en from loss-of-function experiments. However, this issue could be addressed by examining commissural ensheathment, extension of MG processes into the commissures, and the neuronal accumulation of Nrx-IV in en misexpression embryos. In wild-type embryos, MG fully ensheathed the commissures (Fig. 6A), projected membrane projections extensively into the commissures (Fig. 6A′,A″) and had high levels of Nrx-IV accumulation within the commissures (Fig. 6B). By contrast, in sim-Gal4 UAS-en embryos, the resulting MG did not completely ensheath the axon commissures (Fig. 6C), there was an absence of membrane projections into the commissures (Fig. 6C′,C″) and only low levels of Nrx-IV accumulation (Fig. 6D). These results indicate that en is able to impart on MG properties similar to PMG. Analysis of sim-Gal4 UAS-hh embryos showed similar results to sim-Gal4 UAS-en, but the effects were even more severe in their relative lack of MG ensheathment of axons and Nrx-IV accumulation (Fig. 6E,F). These results are consistent with the view that hh imparts a PMG fate on MG, and that en is a significant hh-effector gene. sim-Gal4 UAS-runt embryos were examined and, similar to wild-type AMG, all MG were able to ensheath axons (Fig. 6G), extend cellular projections (Fig. 6G′,G″) and accumulate high levels of Nrx-IV (Fig. 6H). By stage 17, all sim-Gal4 UAS-en and sim-Gal4 UAS-hh MG had undergone apoptosis (not shown). At stage 15, sim-Gal4 UAS-runt embryos showed increased numbers of MG compared with wild type (Fig. 6G) but, by stage 17, apoptosis had reduced the number to wild-type levels (not shown). Although the absence of MG in en and hh misexpression embryos at stage 17 is consistent with a PMG fate, the fact that apoptosis is also a common fate for AMG renders cell number a relatively weak indicator of MG cell fate.

Fig. 6.

en directs posterior midline glia (PMG) cell fate. (A,C,E,G) Sagittal views of segments from stage 15 sim-Gal4 UAS-tau-GFP embryos stained with MAb BP102 (magenta, axon commissures) and anti-GFP (green, midline cells). (A′,C′,E′,G′) MG (GFP channel; white) surround the anterior commissure (AC). Arrows point to midline glia (MG) projections into the AC. (A″,C″,E″,G″) MG surrounding the posterior commissure (PC). (B,D,F,H) Horizontal views of the AC. Dotted lines indicate the anterior and posterior boundaries of the AC. The PC is not completely ensheathed at stage 15, and is not shown. Nrx-IV staining (green) within commissural axons is adjacent to MG projections. (A-A″) In wild-type embryos, three AMG ensheath the AC and extend projections into the commissures. (B) In wild-type embryos, axonal Nrx-IV accumulates at the sites of contact (arrowheads) between AMG projections and AC axons. (C-C′,E-E′) Misexpression of en and hh results in incomplete ensheathment of the commissures, an absence of MG projections and (D,F) a strong reduction in Nrx-IV accumulation at sites of MG-axonal contact. In both sim-Gal4 UAS-en and sim-Gal4 UAS-hh embryos, the normal separation of the anterior and posterior commissures is disrupted to a varying degree. This is consistent with previous work showing that genetic defects in MG number, migration and ensheathment result in commissure separation defects (Klämbt et al., 1991; Noordermeer et al., 1998; Wheeler et al., 2009). (G-G″) Misexpression of runt does not affect ensheathment or MG projections (arrows). There are excess MG present compared with wild type. (H) As in wild type, runt misexpression results in Nrx-IV accumulation at sites of MG-axonal contact.

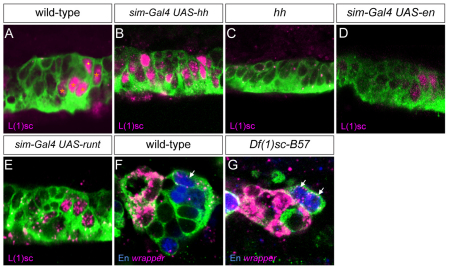

As both en and hh have similar effects on PMG gene expression and development, is en required for all aspects of hh control of PMG fate, or does hh activate expression of additional PMG-expressed genes? The data reported above indicate that, similar to hh, en represses AMG gene expression, has the same limited effect on mas PMG expression when assayed by misexpression and can impart PMG properties with respect to axon ensheathment. To address this issue in more detail, we analyzed the l(1)sc gene, which is expressed in PMG but not AMG, at stages 10-12 (Fig. 7A). The l(1)sc gene was also expressed in all MPs and the MNB (Fig. 7A). Expression of l(1)sc expanded to all MG in hh misexpression embryos (Fig. 7B) and was absent in hh mutants (Fig. 7C), indicating that its expression at stages 11-12 requires hh. However, misexpression of en failed to expand l(1)sc expression to additional MG (Fig. 7D), and loss of en in runt misexpression embryos also did not affect the expression of l(1)sc in PMG (Fig. 7E). These data indicate that hh controls expression of l(1)sc independently of en and, thus, en does not mediate all of the effects of hh on PMG gene expression.

Fig. 7.

L(1)sc posterior midline glia (PMG) expression is regulated by hh but not en. (A) In wild-type embryos, L(1)sc is present in PMG (orange asterisks) and midline neurons (dot) at stage 12. (B) Misexpression of hh results in the presence of L(1)sc in all MG, whereas (C) L(1)sc is absent from the midline cells in hh mutant embryos. (D) Misexpression of en does not result in expansion of L(1)sc. (E) In runt misexpression embryos, l(1)sc expression is unaffected. (F,G) PMG (arrows; En+ low wrapper+ cells) are present in both wild-type (F) and l(1)sc mutant (Df(1)sc-B57) (G) embryos.

The l(1)sc gene encodes a bHLH transcription factor that plays an important role in Drosophila neural precursor formation (Jimenez and Campos-Ortega, 1990; Younossi-Hartenstein et al., 1997). We investigated the potential role of l(1)sc in PMG gene expression and development by analyzing embryos from Df(1)sc-B57, which is a deletion of the achaete-scute complex genes, including l(1)sc. In mutant embryos, PMG were present and expression of en and wrapper was similar to that observed in wild type (Fig. 7F,G). At stage 14, wild-type embryos had 1.9 PMG per segment (n=9 segments examined) and Df(1)sc-B57 mutant embryos had 1.9 PMG per segment (n=15 segments). Thus, l(1)sc does not have a major effect on PMG gene expression or development.

DISCUSSION

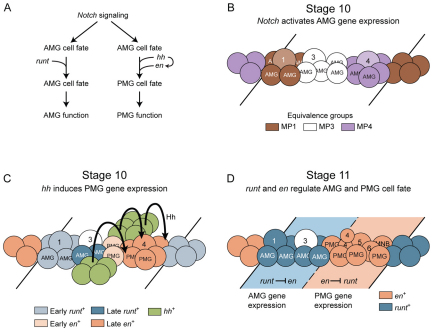

In this paper, we describe how the Hh morphogen patterns the midline cells to generate two populations of MG with distinct functional properties (Fig. 8A). The key output of this signaling is the expression of en that imparts PMG cell fate, in part, by repressing runt. In turn, the runt gene maintains AMG fate by repressing en. Thus, morphogenetic signaling and transcriptional regulation lead to AMG and PMG with divergent molecular, morphological and functional differences.

Fig. 8.

Model of hh, en and runt regulation of midline glia (MG) cell fate. (A) Flow diagram describing the genetic regulation of anterior midline glia (AMG) and posterior midline glia (PMG) development. (B,C) Schematics of stage 10 segments. Anterior is to the left and lines indicate segmental boundaries. (B) Notch signaling results in the activation of MG gene expression and the formation of MP1 (1), MP3 (3) and MP4 (4) from three equivalence groups. (C) Hh, originating in cells lateral to the midline, signals (arrows) to the midline cells that are posterior to the early en+ cells, activating late en expression. Late runt is initiated in cells flanking the early runt+ cells. MP1 is shown arising from early runt+ cells, as it is runt+ and forms during stage 10 prior to the initiation of late runt expression. The early en+ cells are shown as PMG and not AMG, MP1, MP3-6, or the median neuroblast (MNB), because: (1) AMG, MP1 and MP3 arise from en− cells (Wheeler et al., 2006); (2) MP4 arises from en− cells just posterior to the early en+ cells (Fig. 2B′); and (2) MP5, MP6 and the MNB all arise posterior to MP4 (Wheeler et al., 2006). This leaves only PMG as the descendants of the early en+ cells. The other two PMG arise from the late en+ cells, along with MP4-6 and the MNB. (D) Schematic of early stage 11, in which the MP4 has divided into two ventral unpaired median 4 (VUM4) neurons (4). Other MPs are designated 1, 3, 5 and 6, along with the MNB. Dashed line indicates the boundary between runt+ and en+ domains. In the runt+ domain, runt represses en expression, and in the en+ domain, en represses runt expression. This cross-repression maintains distinct AMG and PMG cell fates. MP, midline precursor.

At stage 10, the 16 midline cells per segment consist of three equivalence groups of neural precursors, four to six cells each (Fig. 8B). Notch signaling directs ten of these 16 cells to become MG; the remainder become MPs and the MNB (Wheeler et al., 2008). Thus, Notch represses neuronal development in MG and activates a core set of MG-expressed genes (e.g. wrapper). MG in the anterior of the segment become AMG; those in the posterior of the segment become PMG. Notch signaling by itself is unlikely to influence different MG fates, as expression of activated Suppressor of Hairless in midline cells drives all cells into a MG fate but does not affect their AMG or PMG patterns of gene expression (Wheeler et al., 2008). Thus, additional factors that can direct AMG and PMG cell fates were sought.

Previous work demonstrated that hh can pattern midline cells along the A/P axis (Bossing and Brand, 2006), and, indeed, we demonstrate that hh is required for PMG cell fate. The source of Hh is not in the midline, but in the lateral ectoderm in a stripe of cells, collinear with the pair of midline early en+ cells. Hh signals to midline cells posterior to the early en+ cells, inducing en in an additional six to seven cells (Fig. 8C). These late en+ cells plus the early en+ cells become about four PMG, as well as MP4-6 and the MNB (Fig. 8D). Misexpression and mutant analyses indicate that hh is required for all PMG gene expression and for repressing AMG expression. hh signaling probably has multiple target genes because hh is required for en and l(1)sc expression, but en does not regulate l(1)sc. Misexpression of hh can activate en expression in anterior MG, and both hh and en misexpression convert these cells functionally into non-ensheathing MG that resemble PMG, results also consistent with observations by Bossing and Brand (Bossing and Brand, 2006) that ectopic expression of hh and en in midline cells affects AMG differentiation. However, neither hh nor en can activate all PMG gene expression in anterior MG, because neither activates mas expression in anterior MG. The mas gene is expressed transiently at stage 12 in a subset of PMG, suggesting that functionally distinct classes of PMG might exist. Expression of mas might require other signals in addition to hh that are absent in anterior MG.

runt is present in AMG and represses en and PMG-specific gene expression. In runt mutant cells that are runt− en+, expression of three genes expressed in only AMG (CG33275, Fhos and nemy) are absent and wrapper is reduced. This could be due to runt repression of en, repression of other genes or activation by runt. In runt mutant cells that are runt− en−, Fhos and nemy are present, wrapper is at high levels, but CG33275 expression is absent. This suggests that runt does not activate expression of Fhos, nemy and wrapper in AMG, but maintains their AMG levels by repressing en. By contrast, runt is required for expression of CG33275, possibly indicating a positive role for runt in AMG differentiation in addition to its repressive role in AMG maintenance. However, CG33275 is most prominently expressed in a subset of AMG closest to the commissures (Fig. 1F), and this AMG expression could be dependent on additional signals, perhaps from the developing axon commissure. Thus, absence of CG33275 expression in runt mutant embryos could alternatively be due to an effect of runt on developing axons or CNS development.

As most AMG gene expression is not dependent on runt, we propose that Notch signaling initially induces an AMG pattern of gene expression in all glia (Fig. 8A,B) and, either simultaneously or soon after, Hh signaling in the posterior of the segment generates PMG (Fig. 8C). One important downstream target of Notch signaling is likely to be the sim gene, which encodes a bHLH-PAS protein that functions as a DNA-binding heterodimer with the Tango (Tgo) bHLH-PAS protein (Nambu et al., 1991; Sonnenfeld et al., 1997). During early development, sim is expressed in all midline primordia and is required for midline cell development (Nambu et al., 1990). However, later in development, sim is restricted to MG and a subset of midline neurons (Crews et al., 1988; Wheeler et al., 2008). Genetically, sim expression is absent in embryos mutant for Notch signaling (Wheeler et al., 2008). The sim gene is likely to be an important aspect of MG transcription, because mutation of Sim-Tgo binding sites in the slit and wrapper MG enhancers results in loss of MG expression (Estes et al., 2008; Wharton et al., 1994), and Sim-Tgo binding sites are present in other identified MG enhancers (Fulkerson and Estes, 2010). The Hh morphogen only transforms posterior MG into PMG. It is unknown why hh does not affect anterior MG, but it is likely to be owing to the presence of unknown factors in these cells that inhibit hh signaling. As Notch signaling, rather than runt, is primarily required for AMG gene expression, the key role of runt is probably to maintain AMG gene expression by repressing en. Similarly, en functions to maintain PMG gene expression by repressing runt, but also contributes positively to PMG cell fate, as en misexpression confers PMG-like function to AMG.

The most striking features of AMG are their ability to migrate around the commissures, ensheath them and extend processes into the axons. The function of PMG is unknown, but they are unable to ensheath the commissures, even though they are in close proximity. One of the major factors influencing AMG-axon interactions is Nrx-IV-Wrapper adhesion (Stork et al., 2009; Wheeler et al., 2009). Levels of wrapper expression in AMG are higher than in PMG, and this is likely to be a key determinant of why AMG ensheath commissures, and PMG do not, because loss of wrapper expression results in incomplete migration and ensheathment (Noordermeer et al., 1998; Stork et al., 2009; Wheeler et al., 2009). Recent work has demonstrated that sim directly regulates wrapper expression, and spitz signaling from axons might also form a positive feedback loop to control wrapper levels and strengthen Nrx-IV-Wrapper interactions (Crews, 2009; Estes et al., 2008). As en genetically reduces wrapper levels in PMG, it will be interesting to determine if this regulation is direct or indirect. Although the control of wrapper levels is likely to be a major factor in AMG-PMG differences and the ability of glia to ensheath axons, other genes whose levels differ between AMG and PMG might also contribute. This illustrates why it will be important to identify target genes and understand better the roles that Notch//Suppressor of Hairless, sim, hh, Ci, en, runt and other MG transcription factors play in regulating MG gene expression and function.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (University of Iowa) for monoclonal antibodies; the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, Peter Gergen, Matt Scott and John-Paul Vincent for Drosophila strains; Tony Perdue for assistance with microscopy; and Yash Hiromi for special assistance. This work was supported by NIH grants R01 NS64264 (NINDS) and R37 RD25251 (NICHD) to S.T.C., and UNC Developmental Biology NIH training grant fellowships to S.B.S. and J.D.W. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Alexandre C., Vincent J. P. (2003). Requirements for transcriptional repression and activation by Engrailed in Drosophila embryos. Development 130, 729-739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen N. J., Barres B. A. (2009). Neuroscience: Glia-more than just brain glue. Nature 457, 675-677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner S., Littleton J. T., Broadie K., Bhat M. A., Harbecke R., Lengyel J. A., Chiquet-Ehrismann R., Prokop A., Bellen H. J. (1996). A Drosophila neurexin is required for septate junction and blood-nerve barrier formation and function. Cell 87, 1059-1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann A., Tugentman M., Shilo B. Z., Steller H. (2002). Regulation of cell number by MAPK-dependent control of apoptosis: a mechanism for trophic survival signaling. Dev. Cell 2, 159-170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossing T., Brand A. H. (2006). Determination of cell fate along the anteroposterior axis of the Drosophila ventral midline. Development 133, 1001-1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand A. (1995). GFP in Drosophila. Trends Genet. 11, 324-325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R. M., Peterson A. C. (1993). Expression of a lacZ transgene reveals floor plate cell morphology and macromolecular transfer to commissural axons. Development 119, 1217-1228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Struhl G. (1996). Dual roles for patched in sequestering and transducing Hedgehog. Cell 87, 553-563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews S. T. (2003). Drosophila bHLH-PAS developmental regulatory proteins. In PAS Proteins: Regulators and Sensors of Development and Physiology (ed. Crews S. T.), pp. 69-108 Boston, MA: Kluwer; [Google Scholar]

- Crews S. T. (2009). Axon-glial interactions at the Drosophila CNS midline. Cell Adh. Migr. 4, 66-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews S. T., Thomas J. B., Goodman C. S. (1988). The Drosophila single-minded gene encodes a nuclear protein with sequence similarity to the per gene product. Cell 52, 143-151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong R., Jacobs J. R. (1997). Origin and differentiation of supernumerary midline glia in Drosophila embryos deficient for apoptosis. Dev. Biol. 190, 165-177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes P., Fulkerson E., Zhang Y. (2008). Identification of motifs that are conserved in 12 Drosophila species and regulate midline glia vs. neuron expression. Genetics 178, 787-799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulkerson E., Estes P. A. (2010). Common motifs shared by conserved enhancers of Drosophila midline glial genes. J. Exp. Zool. B. Mol. Dev. Evol. 316, 61-75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gergen J. P., Wieschaus E. (1986). Dosage requirements for runt in the segmentation of Drosophila embryos. Cell 45, 289-299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubb D. (1985). Further studies on engrailed mutants in Drosophila melanogaster. Roux's Arch. Dev. Biol. 194, 236-246 [Google Scholar]

- Guillen I., Mullor J. L., Capdevila J., Sanchez-Herrero E., Morata G., Guerrero I. (1995). The function of engrailed and the specification of Drosophila wing pattern. Development 121, 3447-3456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustavson E., Goldsborough A. S., Ali Z., Kornberg T. B. (1996). The Drosophila engrailed and invected genes: partners in regulation, expression and function. Genetics 142, 893-906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo A., Ingham P. (1990). Cell patterning in the Drosophila segment: spatial regulation of the segment polarity gene patched. Development 110, 291-301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaynes J. B., Fujioka M. (2004). Drawing lines in the sand: even skipped et al. and parasegment boundaries. Dev. Biol. 269, 609-622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez F., Campos-Ortega J. A. (1990). Defective neuroblast commitment in mutants of the achaete-scute complex and adjacent genes of D. melanogaster. Neuron 5, 81-89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearney J. B., Wheeler S. R., Estes P., Parente B., Crews S. T. (2004). Gene expression profiling of the developing Drosophila CNS midline cells. Dev. Biol. 275, 473-492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klämbt C., Jacobs J. R., Goodman C. S. (1991). The midline of the Drosophila central nervous system: a model for the genetic analysis of cell fate, cell migration, and growth cone guidance. Cell 64, 801-815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosman D., Small S., Reinitz J. (1998). Rapid preparation of a panel of polyclonal antibodies to Drosophila segmentation proteins. Dev. Genes Evol. 208, 290-294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen C. W., Hirst E., Alexandre C., Vincent J. P. (2003). Segment boundary formation in Drosophila embryos. Development 130, 5625-5635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. J., von Kessler D. P., Parks S., Beachy P. A. (1992). Secretion and localized transcription suggest a role in positional signaling for products of the segmentation gene hedgehog. Cell 71, 33-50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menne T. V., Klämbt C. (1994). The formation of commissures in the Drosophila CNS depends on the midline cells and on the Notch gene. Development 120, 123-133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirsky R., Woodhoo A., Parkinson D. B., Arthur-Farraj P., Bhaskaran A., Jessen K. R. (2008). Novel signals controlling embryonic Schwann cell development, myelination and dedifferentiation. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 13, 122-135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nambu J. R., Franks R. G., Hu S., Crews S. T. (1990). The single-minded gene of Drosophila is required for the expression of genes important for the development of CNS midline cells. Cell 63, 63-75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nambu J. R., Lewis J. L., Wharton K. A., Crews S. T. (1991). The Drosophila single-minded gene encodes a helix-loop-helix protein which acts as a master regulator of CNS midline development. Cell 67, 1157-1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noordermeer J. N., Kopczynski C. C., Fetter R. D., Bland K. S., Chen W. Y., Goodman C. S. (1998). Wrapper, a novel member of the Ig superfamily, is expressed by midline glia and is required for them to ensheath commissural axons in Drosophila. Neuron 21, 991-1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusslein-Volhard C., Wieschaus E. (1980). Mutations affecting segment number and polarity in Drosophila. Nature 287, 795-801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel N. H., Martin-Blanco E., Coleman K. G., Poole S. J., Ellis M. C., Kornberg T. B., Goodman C. S. (1989). Expression of engrailed proteins in arthropods, annelids, and chordates. Cell 58, 955-968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter J. A., Ekker S. C., Park W. J., von Kessler D. P., Young K. E., Chen C. H., Ma Y., Woods A. S., Cotter R. J., Koonin E. V., et al. (1996). Hedgehog patterning activity: role of a lipophilic modification mediated by the carboxy-terminal autoprocessing domain. Cell 86, 21-34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenfeld M. J., Jacobs J. R. (1995). Apoptosis of the midline glia during Drosophila embryogenesis: a correlation with axon contact. Development 121, 569-578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenfeld M., Ward M., Nystrom G., Mosher J., Stahl S., Crews S. (1997). The Drosophila tango gene encodes a bHLH-PAS protein that is orthologous to mammalian Arnt and controls CNS midline and tracheal development. Development 124, 4571-4582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stollewerk A., Klämbt C. (1997). The midline glial cells are required for regionalization of commissural axons in the embryonic CNS of Drosophila. Dev. Genes Evol. 207, 402-409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stork T., Thomas S., Rodrigues F., Silies M., Naffin E., Wenderdel S., Klämbt C. (2009). Drosophila Neurexin IV stabilizes neuron-glia interactions at the CNS midline by binding to Wrapper. Development 136, 1251-1261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracey W. D., Ning X., Klingler M., Kramer S. G., Gergen J. P. (2000). Quantitative analysis of gene function in the Drosophila embryo. Genetics 154, 273-284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai C., Gergen J. P. (1994). Gap gene properties of the pair-rule gene runt during Drosophila segmentation. Development 120, 1671-1683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wharton K. A., Franks R. G., Kasai Y., Crews S. T. (1994). Control of CNS midline transcription by asymmetric E-box elements: similarity to xenobiotic responsive regulation. Development 120, 3563-3569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler S. R., Kearney J. B., Guardiola A. R., Crews S. T. (2006). Single-cell mapping of neural and glial gene expression in the developing Drosophila CNS midline cells. Dev. Biol. 294, 509-524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler S. R., Stagg S. B., Crews S. T. (2008). Multiple Notch signaling events control Drosophila CNS midline neurogenesis, gliogenesis and neuronal identity. Development 135, 3071-3079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler S. R., Banerjee S., Blauth K., Rogers S. L., Bhat M. A., Crews S. T. (2009). Neurexin IV and wrapper interactions mediate Drosophila midline glial migration and axonal ensheathment. Development 136, 1147-1157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieschaus E., Nusslein-Volhard C., Jurgens G. (1984). Mutations affecting the pattern of the larval cuticle in Drosophila melanogaster. III. Zygotic loci on the X-chromosome and fourth chromosome. Roux's Arch. Dev. Biol. 193, 296-307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H., Hrdlicka L. A., Nambu J. R. (1996). Alternate functions of the single-minded and rhomboid genes in development of the Drosophila ventral neuroectoderm. Mech. Dev. 58, 65-74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka T., Tanaka O. (1989). Ultrastructural and cytochemical characterisation of the floor plate ependyma of the developing rat spinal cord. J. Anat. 165, 87-100 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younossi-Hartenstein A., Green P., Liaw G. J., Rudolph K., Lengyel J., Hartenstein V. (1997). Control of early neurogenesis of the Drosophila brain by the head gap genes tll, otd, ems, and btd. Dev. Biol. 182, 270-283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B., Pennack J. A., McQuilton P., Forero M. G., Mizuguchi K., Sutcliffe B., Gu C. J., Fenton J. C., Hidalgo A. (2008). Drosophila neurotrophins reveal a common mechanism for nervous system formation. PLoS Biol. 6, e284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]