Abstract

This longitudinal, mixed method study focused on 57 families of children who participated in a mentoring program for children of incarcerated parents. Children ranged in age from 4 to 15 years. Monthly interviews were conducted with children, caregivers, and mentors during the first six months of program participation, and questionnaires were administered at intake and six months to assess caregiver–child and incarcerated parent–child relationships, contact with incarcerated parents, and children’s behavior problems. Although some children viewed their incarcerated parents as positive attachment figures, other children reported negative feelings toward or no relationship with incarcerated parents. In addition, our assessments of children nine years old and older revealed that having no contact with the incarcerated parent was associated with children reporting more feelings of alienation toward that parent compared to children who had contact. Children’s behavior problems were a primary concern, often occurring in a relational context or in reaction to social stigma associated with parental imprisonment.

Keywords: attachment, behavior problems, parental incarceration, relationships, visitation

Introduction

The number of children with incarcerated parents is growing rapidly in the United States (Mumola, 2000). More than 1.7 million children have a parent in state or federal prison (Glaze & Maruschak, 2008), and children of incarcerated parents experience increased risk for antisocial outcomes, internalizing symptoms, and academic difficulties (Murray & Farrington, 2008a). Although children of incarcerated parents often experience significant disruptions in their family relationships because of changes in caregivers and separation from imprisoned parents (Poehlmann, 2003, 2005a), few empirical studies of children with incarcerated parents have focused on the quality of attachment or caregiving relationships, aside from those presented in this special issue. In the current study, we documented children’s feelings about their relationships with caregivers and incarcerated parents, assessed caregivers’ perceptions and feelings about children, and examined associations among relationship perceptions, contact with imprisoned parents, and behavior problems in children of incarcerated parents in the context of a youth mentoring program.

In his seminal writings about attachment, Bowlby (1982) drew on ethological research and theory that pointed to a number of instinctive behavioral systems that facilitate survival, including attachment and caregiving. A key function of the child’s attachment system is to maintain proximity to an attachment figure in order to ensure the child’s protection (Ainsworth, 1990; Bowlby, 1973). The caregiving system in the parenting figure is concerned with protecting and supporting the child while striking a balance with other personal goals (George & Solomon, 2008). Since its inception, attachment theory has emphasized the negative effects of separation from parents on children’s attachments and subsequent developmental outcomes (Bowlby, 1980; Robertson, 1953). Because most children of incarcerated parents experience disruptions in family relationships that occur as the result of separations and changing living arrangements (e.g., Poehlmann, 2005a), an attachment perspective is well-suited to examine these processes.

In one of the few empirical studies to investigate the attachment or caregiving systems in families affected by parental incarceration, Poehlmann (2005a) used the Attachment Story Completion Task (ASCT; Bretherton, Ridgeway, & Cassidy, 1990) to assess attachment representations in 54 children between the ages of 2.5 and 7.5 years whose mothers were incarcerated. She found that most (63%) children were classified as having insecure relationships with nonmaternal caregivers and incarcerated mothers. Compared to children who had experienced multiple caregivers since their mother’s incarceration, children who had been consistently cared for by one individual were more likely to be classified as secure. Additionally, in a study focusing on 79 children living with custodial grandparents, half of whom had incarcerated mothers, Poehlmann and colleagues found that children who depicted less optimal family relationships on the ASCT were rated by their caregivers as exhibiting more externalizing behavior problems (Poehlmann, Park, Bouffou, Abrahams, Shlafer, & Hahn, 2008).

The importance of the caregiving environment for children of incarcerated parents has often been neglected in the literature (Cecil, McHale, Strozier, & Pietsch, 2008), although it is caregivers who have daily interactions and communication with children during a parent’s imprisonment. Poehlmann (2005b) found that quality of the child’s caregiving environment predicted the cognitive development of young children raised by relatives as the result of maternal incarceration. Moreover, in a study of 6–12-year-old children whose mothers were incarcerated, Mackintosh, Myers, and Kennon (2006) found that children reported fewer behavior problems when they felt more warmth and acceptance from their caregivers. Attachment theory also suggests that disruptions in children’s attachment relationships, such as those that occur when children move from one caregiver to another, can have detrimental effects (e.g., Bowlby, 1944, 1973; Kobak & Madsen, 2008).

Many studies have documented elevated rates of behavior problems in children of incarcerated parents (see Murray & Farrington, 2008a, for a review), although developmental and familial processes leading to these problems remain unclear. In their analysis of longitudinal data from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development, Murray and Farrington (2005, 2008b) found that boys who were separated from a parent before 10 years old because of parental incarceration were more likely to exhibit internalizing symptoms and antisocial outcomes in adolescence and adulthood than boys who experienced other kinds of childhood separations from parents. These findings remained significant after controlling for parental criminality and other family risks, although analyses of data from a Swedish longitudinal study did not replicate these findings (Murray, Janson, & Farrington, 2007). Despite the importance of these studies, quality of family relationships, caregiving stability, and children’s contact with incarcerated parents were not assessed.

Most research examining parent–child contact during a parent’s incarceration has focused on the perceptions and attitudes of incarcerated parents (Tuerk & Loper, 2006) rather than on children’s experiences. Several studies have found that when incarcerated parents receive visits from children, parents report more positive feelings about their children (e.g., Snyder, Carlo, & Mullins, 2001). However, the few studies that have assessed children’s outcomes in relation to contact have yielded mixed findings. In Poehlmann’s (2005a) study of young children whose mothers were incarcerated, there was a trend for children who had recently visited their mothers at the prison to have insecure attachment representations. Yet in a study of 58 adolescents with incarcerated mothers, youth who had more frequent contact with their imprisoned mothers were less likely to experience school drop out or suspensions (Trice & Brewster, 2004). Findings from probability samples of prisoners in the United States have found that few imprisoned parents receive regular visits from their children, although letters and telephone calls occur more frequently (Glaze & Maruschak, 2008; Mumola, 2000). Maintaining contact can be difficult for many reasons, including location of the prison, cost of travel or telephone calls, and conflicted family relationships (Myers, Smarsh, & Amlund-Hagan, 1999; Poehlmann, 2005c). In addition, caregivers typically regulate children’s contact with incarcerated parents, particularly when children are young (Enos, 2001; Poehlmann, Shlafer, Maes, & Hanneman, 2008).

Recently, mentoring has come to the attention of policy makers and practitioners as an intervention that can address some of the needs of children with incarcerated parents. The present study utilized data collected as part of a study examining children’s participation in Mentoring Connections (MC), a mentoring program funded by the Department of Health and Human Services that was designed to serve children with an incarcerated parent. In this article, we focus on children’s relationships with caregivers and incarcerated parents. Findings regarding the program evaluation and children’s relationships with mentors are forthcoming (Shlafer, Poehlmann, Coffino, & Hanneman, 2009).

The primary goal of our study was to use an attachment perspective to examine children’s and caregivers’ perceptions and feelings about the caregiver–child relationship and the contact between the child and the incarcerated parent, stability of the caregiving situation, and children’s behavior problems. We also examined how children’s mentors and teachers perceived these issues. The study used a longitudinal design that included both qualitative methods (e.g., thematic content analysis of interviews) and quantitative methods (e.g., statistical analysis of questionnaire data), referred to as a “mixed method, concurrent nested longitudinal design” (Creswell, Plano Clark, Guttmann, & Hanson, 2003). Interpretations were made on the basis of both qualitative and quantitative analyses. This design was used to address the following questions:

What are children’s perceptions and feelings about their relationships with incarcerated parents, and how do these feelings compare to children’s feelings about their relationships with current caregivers?

How do children and caregivers view contact with the incarcerated parent, and does contact relate to children’s perceptions and feelings about the relationship with the incarcerated parent or to children’s behavior problems?

Are children’s and caregivers’ perceptions about the child–caregiver relationship associated with children’s behavior problems in families affected by parental incarceration?

Does stability of the caregiving situation in families affected by parental incarceration relate to children’s perceptions and feelings about their relationships with caregivers and incarcerated parents or to children’s behavior problems?

Method

Participants

Children of incarcerated parents were enrolled in the present study as part of Mentoring Connections (MC), a community collaboration between Big Brothers Big Sisters (BBBS) of Dane County, Wisconsin, Madison-Area Urban Ministry, and the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Any child who was referred to MC and matched with a mentor was invited to participate in the study; there was a 100% participation rate. Between March 2005 and November 2006, 57 matches were made. As a result of match termination, attrition, children’s age, and missing data, the sample size for most of the quantitative analyses is smaller than 57 (see Table 1). There were no statistically significant differences between families who terminated from the program early and those who continued to six months on any characteristics of the mentors (gender, age, ethnicity), children (gender, age, ethnicity, relationship to caregiver, behavior problems, IPPA scores), or caregivers (marital status, education, ethnicity, income), with the exception that families who continued in the program experienced more cumulative sociodemographic risks than those who terminated early (Shlafer et al., 2009). We refer to the child’s entry into the mentoring program as the “intake” timepoint. In all cases, the parent had been incarcerated prior to the child’s entry into the mentoring program.

Table 1.

Data collected at each timepoint.

| Intake | Month 1 | Month 2 | Month 3 | Month 4 | Month 5 | Month 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children with incarcerated | Children with incarcerated | Children with incarcerated | Children with incarcerated | Children with incarcerated | Children with incarcerated | Children with incarcerated |

| fathers: n = 49 | fathers: n = 38 | fathers: n = 33 | fathers: n = 28 | fathers: n = 23 | fathers: n = 16 | fathers: n = 17 |

| mothers: n = 4 | mothers: n = 4 | mothers: n = 2 | mothers: n = 2 | mothers: n = 2 | mothers: n = 3 | mothers: n = 2 |

| both: n = 4 | both: n = 4 | both: n = 3 | both: n = 2 | both: n = 3 | both: n = 2 | both: n = 0 |

| Caregiver and child interviews n = 57 | Caregiver and child interviews n = 46 | Caregiver and child interviews n = 38 | Caregiver and child interviews n = 32 | Caregiver and child interviews n = 28 | Caregiver and child interviews n = 21 | Caregiver and child interviews n = 19 |

| Mentor interviews n = 57 | Mentor interviews n = 47 | Mentor interviews n = 45 | Mentor interviews n = 44 | Mentor interviews n = 41 | Mentor interviews n = 36 | Mentor interviews n = 39 |

| Contact data n = 57 | Contact data n = 46 | Contact data n = 38 | Contact data n = 34 | Contact data n = 27 | Contact data n = 21 | Contact data n = 21 |

| CBCLa n = 39 | CBCL n = 18 | |||||

| TRFb n = 33 | TRF n = 18 | |||||

| IPPA-IPc (age 9+) n = 24 | IPPA-IP (age 9+) n = 12 | |||||

| IPPA-CGd (age 9+) n = 27 | IPPA-CG (age 9+) n = 14 | |||||

| R-IPAe (age 7+) n = 40 | R-IPA (age 7+) n = 18 |

Note: 51 children participated in at least one monthly interview. Sometimes the number of interviews exceeded the number of participants still actively involved in mentoring because ‘termination’ or ‘closeout’ interviews were conducted when possible.

CBCL = Caregivers’ reports on the Child Behavior Checklist.

TRF = Teachers’ reports on the Teacher Report Form.

IPPA-IP = Children’s self-reported feelings about their incarcerated parents on the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment.

IPPACG = Children’s self-reported feelings about their caregivers on the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment.

R-IPA = Caregivers’ reports of their relationships with children on the Revised Inventory of Parent Attachment.

At intake, children ranged in age from 4 to 15 years (M = 9.13, SD = 3.00) and the majority were girls (60%, n = 34). Most children had incarcerated fathers only (86%, n = 49), although four children had incarcerated mothers only (7%) and, for four children, both parents were incarcerated (7%). Because mostly fathers were incarcerated, the majority of children lived with their biological mothers (79%, n = 45); thus, the term “caregiver” refers to the child’s mother in most cases. Nearly all children were from minority racial or ethnic groups (93%, n = 53), and most families (68%, n = 39) lived below the federal poverty line (determined using the 2005 Health and Human Services Poverty Guidelines; Health and Human Services Poverty Guidelines, 2005). Many families experienced additional sociodemographic risk factors; for example, 84%(n = 48) received public assistance, most caregivers were not married (n = 49, 86%), 35% (n = 20) of caregivers had less than a high school education, and 23% of the families had four or more children living in the home (n = 13).

Measures

Measures administered at each timepoint are summarized in Table 1.

Interview responses about contact and relationships

Semi-structured interviews with caregivers, children, and mentors were conducted at intake and each month during the first six months of children’s participation in the program. Interviews inquired about several areas in the child’s life. Specifically, caregivers were asked What seems to be going particularly well with the child? Have there been any goals or achievements in the past month that the child has accomplished? Have there been any problems with the child in the last month? Caregivers and children were also asked to discuss the frequency and type of contact between incarcerated parents and children, as well as caregivers’ feelings about contact. A total of 184 interviews were conducted with children, 184 interviews were conducted with children’s caregivers, and 252 interviews were conducted with mentors across the first six months of the program. Detailed notes and direct quotations were written by research assistants when they conducted the telephone interviews and, following the interviews, research assistants expanded upon their notes. All interview notes were later coded using a grounded-theory approach (Strauss & Corbin, 1997). In particular, monthly interviews were analyzed using an open-coding technique to identify initial codes, emergent themes, and links between themes (Strauss & Corbin, 1997).

Children’s perceptions and feelings concerning parent–child relationships

The Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA; Armsden, 1986; Armsden & Greenberg, 1987) was used to assess children’s perceptions and feelings about the caregiver–child and incarcerated parent–child relationship. The IPPA was administered to children (who were nine years and older) at intake and at six months. The IPPA is a self-report measure containing 25 items that assesses affective and cognitive dimensions of adolescents’ relationships with parents and friends. Examples of positively-worded items on the parent scale include My mother understands me and I trust my mother. Examples of negatively-worded items include My mother has her own problems so I don’t bother her with mine and Talking over problems with my mother makes me feel ashamed or foolish.

The IPPA has been used in numerous studies exploring attachment relationships with younger (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987; Armsden, McCauley, & Greenberg, 1990; Papini & Roggman, 1992; Papini, Roggman, & Anderson, 1991) and older adolescents (e.g., Brack, Gay, & Matheny, 1993; McCarthy, Moller, & Fouladi, 2001). Armsden and Greenberg (1987) reported high internal consistency, with Cronbach alpha coefficients between .86 and .91. IPPA total and subscale scores have been associated with antisocial behavior (Marcus & Betzer, 1996), loneliness and social support (Larose & Boivin, 1997), depression (Armsden et al., 1990), and social anxiety (Papini et al., 1991). Additionally, in their national evaluation of Big Brothers Big Sisters, Tierney, Grossman, and Resch (2000) used the IPPA to explore the effects of mentoring on attachment relationships in youth between 10 and 16 years of age. Internal consistency was high, with alpha coefficients of .86 and .90 at baseline and at 18 months, respectively.

In the current study, children were asked to complete two versions of the form: one for their current caregiver (IPPA-CG) and one for their incarcerated parent (IPPA-IP). We adjusted the wording of the IPPA-CG when the caregiver was not a parent (“caregiver” replaced “mother” or “father” when appropriate). At intake, 27 of the 31 children who were nine years or older completed the IPPA-CG. However, three of these children chose not to complete the IPPA-IP because they felt that they did not have a relationship with the incarcerated parent. Total scores and subscale scores (mutual trust, quality of communication, and anger/alienation) were computed for both measures, with higher scores indicating more positive attachment relationships. Cronbach’s alpha was .86 for the total IPPA-CG and .86 (Trust), .70 (Communication), and .63 (Alienation) for the subscales. Cronbach’s alpha was .92 for the total IPPA-IP at intake and .92 (Trust), .74 (Communication), and .58 (Alienation) at intake. At 6 months, Cronbach’s alpha was .92 for the total IPPA-CG and .94 for the total IPPA-IP.

Caregivers’ perceptions and feelings about the parent–child relationship

The Revised Inventory of Parent Attachment (R-IPA; Johnson, Ketring, & Abshire, 2003) was administered at intake and six months to caregivers with children aged seven years and older to assess the caregiver’s perceptions and feelings about the caregiver–child relationship. Johnson and colleagues (2003) altered the wording of the original IPPA to assess parents’ views of their relationships with their adolescent children. The R-IPA contains 22 items, rated on a five-point scale, with (1) indicating “almost never or never true” and (5) indicating “almost always or always true.” A composite score is calculated by summing the items, with higher scores indicating more positive relationships from the caregiver’s view.

The R-IPA (Johnson et al., 2003) was originally developed using a large sample (n = = 212) of high risk adult parents and their adolescent children (M age = 14.3 years). Johnson and colleagues (2003) found that the trust/avoidance subscale of the R-IPA correlated positively with the communication subscale and negatively with symptom distress, social roles, interpersonal relations, and physical aggression. However, the communication subscale of the R-IPA did not correlate with the other measures of attachment-related variables. In the current study, the total score was used. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha for the R-IPA was .87 at intake and .91 at 6 months.

Children’s behavior problems

Children’s behavior problems were measured at intake and 6 months using caregiver responses to the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and teacher responses to the Teacher Report Form (TRF; Achenbach, 1991). The CBCL and the TRF are widely used and contain 120 problem items rated on a three-point scale, (0) not true, (1) somewhat or sometimes true, or (2) very true or often true. The items fall into one of two broad-band scales: Internalizing and Externalizing Problems. At intake, 18 (32%) of the CBCLs were missing because they were not returned by the caregiver or were not administered by the BBBS case manager. Further, 24 (42%) of the TRFs were missing because they were not returned by the child’s teacher. As a result of attrition and termination of mentor– child relationships, 18 CBCLs and 18 TRFs were completed at six months. Because of the significant correlations between caregiver and teacher reports (average r =.60, p < .01), and to minimize missing data, we calculated the mean of caregiver and teacher reports to create Internalizing and Externalizing T-scores at intake and six months. For the average score variable, if a caregiver report was missing, we used the teacher report (and vice versa), resulting in 47 averaged Internalizing and Externalizing scores at intake and 25 averaged scores at six months.

Teachers also responded to open-ended questions on the TRF. Using an open-coding technique (Strauss & Corbin, 1997), we coded teachers’ responses to the following items: (1) Does this pupil have any illness or disability (either physical or mental)? Please describe. (2) What concerns you most about this pupil? (3) Please describe the best things about this pupil. (4) Please feel free to write any comments about this pupil’s work, behavior, or potential.

Contact with the incarcerated parent

At intake, caregivers were asked to report the frequency of contact, including letters, visits, and telephone calls that occurred between the incarcerated parent and the child prior to program participation on a four-point scale: (0) never, (1) sporadically, (2) holidays, (3) monthly, or (4) weekly or more often. The distribution across these categories were not evenly distributed; thus, for some analyses we compared groups using a binary contact variable, with any contact coded as 1 and no contact coded as 0. During monthly interviews across the first six months of program participation, caregivers were also asked to indicate the frequency of children’s visits and other forms of contact each month with the incarcerated parent. Across the first six months, the frequency of contact between children and their incarcerated parents was very skewed; therefore, in some analyses we also compared groups using a binary variable which represented whether children had any (1) or no (0) contact with the incarcerated parent during the first six months.

Procedure

Approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. A case manager at BBBS was responsible for accepting referrals and matching children and mentors in the program. All children referred to MC were matched with an appropriate mentor as soon as possible, without placement on a waiting list. After children were matched, caregivers and mentors completed consent forms to participate in the program evaluation, and children over nine years old were asked to give their written assent. Caregivers, children, and mentors were followed on a monthly basis for six months. At the start of the program (intake), the case manager administered all measures. Caregivers completed a demographic form, CBCL, R-IPA, and a release of information form so that teachers could be contacted. Children nine years and older completed the IPPA. After the intake paperwork was completed, the school release form and TRF were sent to the child’s teacher. If the TRF was not returned, the teacher was emailed or called and a second TRF was sent. Each month, a research assistant contacted children, caregivers, and mentors by telephone and interviewed them about their experiences during the previous month. If participants could not be reached for more than one month, the case manager contacted the family. If a participant missed an interview but could be reached the following month, the research assistant also asked about the participants’ experiences during the previous month.

Results

We used qualitative and quantitative analyses to address each of the research questions. First, monthly interviews and teachers’ responses to open-ended items were analyzed. Although sample sizes varied across months (see Table 1), 51 children participated in at least one monthly interview. The three emergent themes that we present here were expressed by children and one other group of respondents (i.e., caregivers, teachers, or mentors): children’s perceptions and feelings about relationships with incarcerated parents, children’s contact with incarcerated parents, and the meaning and context of children’s behavior problems. After presentation of each theme, we report the results of quantitative analyses to supplement and extend the qualitative findings. We then examine quantitative analyses related to caregiving stability. Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Bivariate correlations and descriptive statistics for key variables.

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. IPPA-CG intakea | – | |||||||||||

| 2. IPPA-CG 6 mo.a | .76** | – | ||||||||||

| 3. IPPA-IP intakeb | .39 | .18 | – | |||||||||

| 4. IPPA-IP 6 mo.b | .09 | .07 | .68* | – | ||||||||

| 5. R-IPA intakec | .27 | .19 | −.04 | .22 | – | |||||||

| 6. R-IPA 6 mo.c | .39 | .70* | −.00 | .30 | .80** | – | ||||||

| 7. Internalizing intake | .14 | −.10 | .14 | −.20 | −.55** | −.52* | – | |||||

| 8. Externalizing intake | −.22 | −.13 | −.01 | −.20 | −.76** | −.58* | .69** | – | ||||

| 9. Internalizing 6 mo. | −.34 | −.54 | .39 | .28 | −.41 | −.52* | .64** | .61** | – | |||

| 10. Externalizing 6 mo. | −.42 | −.57 | .14 | .12 | −.67 | −.48* | .64** | .70** | .59** | – | ||

| 11. Contact with IP intaked | −.07 | .32 | .12 | .49 | −.03 | .38 | .12 | .12 | .08 | .06 | – | |

| 12. Contact with IP 6 mo.d | −.14 | .02 | −.23 | −e | .29 | .17 | −.15 | −.23 | −.45 | −.36 | .25 | – |

| M | 89.78 | 92.36 | 83.75 | 87.08 | 85.58 | 79.94 | 52.07 | 57.62 | 56.50 | 55.04 | .70 | .79 |

| SD | 15.01 | 18.91 | 21.22 | 23.79 | 12.58 | 14.83 | 10.03 | 10.08 | 12.62 | 11.34 | .46 | .42 |

| Range | 55–113 | 49–115 | 35–115 | 27–115 | 61–109 | 57–102 | 33–72 | 38.5–82 | 36–76 | 33–77.5 | 0–1 | 0–1 |

Note:

IPPA-CG = Children’s self-reported feelings about their caregivers on the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment.

IPPA-IP = Children’s self-reported feelings about their incarcerated parents on the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment.

R-IPA = Caregivers’ reports of their relationships with children on the Revised Inventory of Parent Attachment.

Contact with IP: 0 = no contact, 1 = any contact.

p < .05

p < .01.

Cannot compute because contact with incarcerated parent at six months was a constant for children who completed the IPPA-IP.

Children’s perceptions and feelings about their relationships with incarcerated parents

Qualitative analyses

Despite being asked direct questions about the matter, slightly more than one-third of the children (n = 22; 39%) did not discuss their relationship with their incarcerated parent during any of the interviews. In some of these cases, the caregiver reported that the child had no relationship with the incarcerated parent. For many children, however, the incarceration of the parent had been a meaningful and difficult separation. Of the 29 children who discussed their relationship with the incarcerated parent, 12 (41%) children consistently reported positive feelings or feelings of missing or wanting to be with their incarcerated parents. For example, one child said, “I really miss my dad,” and another child said, “I had a dream that I tore down the prison walls so that I could be with my daddy.” However, nine children (31%) reported primarily negative feelings about the incarcerated parent, including feelings of anger and resentment. One child tore up a card that her father had written to her, and another child said, “I don’t like my [incarcerated] mother; she’s mean.” Other children (28%) reported feeling both positive and negative feelings or confusion (which we term “mixed feelings”). For example, one month a child said she loved her incarcerated father and a few months later she said she hated him. Another child said, “I’m not sure if I want to see my dad.”

Several respondents reported that children disconnected themselves from the relationship over time, distancing themselves from or avoiding their emotional reactions to the incarcerated parent. Resisting discussion or minimizing feelings was also common. For example, one child said, “I don’t really feel anything.” Similarly, one caregiver said, “I tried to talk to him about his dad, but he hasn’t wanted anything to do with him while he is in there [prison].”

In some cases, children and caregivers expressed fear or concern regarding the parent’s impending release from prison. One mentor described her mentee as “Very apprehensive lately. He is scared for his father’s release.” A caregiver said, “She doesn’t want to see him. She is scared and worried about seeing him when he gets out.” Another caregiver gave the child a cell phone to help protect her from the incarcerated parent who had recently been released from prison. In most cases, the fears expressed were vague rather than being focused on a specific event or behavior.

Finally, some children expressed secrecy regarding their relationship with the parent and the parent’s incarceration. Several mentors reported that children revealed information about the incarcerated parent that the children were told by their caregivers not to share. Other children seemed uncomfortable sharing thoughts and feelings about the incarcerated parent during interviews. For example, one child said, “I can’t really share with you.” Other children expressed secrecy regarding ongoing contact with the incarcerated parent, and several older children indicated that they communicated with the incarcerated parent without the caregiver’s knowledge or permission. Another child made a valentine for her incarcerated father and asked the mentor to send it so that the child’s caregiver would not see it.

Quantitative analyses

Using a series of paired samples t-tests, we compared children’s feelings about their relationship with the incarcerated parent to children’s feelings about their relationship with the caregiver, as reported by children nine years of age or older using the IPPA. At intake, children’s overall feelings (IPPA-total) about relationships with incarcerated parents (M = 83.75, SD = 21.22) did not differ significantly from their feelings about relationships with caregivers (M = 89.78, SD = 15.02). Further, there were no significant differences on the trust or alienation subscales. However, there was a trend for children to report slightly more positive communication with caregivers (M = 27.52, SD = 5.34) than with their incarcerated parents (M = 24.63, SD = 6.55), t(22) = −1.88, p < .10. At six months, there were no significant differences between children’s feelings about caregivers or incarcerated parents on any of the scales; however at six months, only 12 children completed IPPAs regarding both their current caregiver and incarcerated parent.

Children’s contact with the incarcerated parent

Qualitative analyses

There was considerable variability in responses regarding children’s contact with the incarcerated parent. Some children reported being unsure about whether or not they wanted to have contact with the incarcerated parent. For instance, one child said, “I don’t know whether or not I want to see him.” One mentor said, “He loves his mommy, but he wishes she would call when she says she’s going to call.” Other children discussed reasons why they were unable to have contact with their incarcerated parent. One child said, “I might want to go see my mom, but my aunt doesn’t have time to drive – it’s far away.” Another child reported, “I can’t talk to him [incarcerated father], because my grandma won’t accept the calls.”

Several children discussed their experiences visiting the incarcerated parent, and none of them reported positive experiences. One child said, “I went to see my father and he didn’t really talk to me.” Another child reported that during the visit, “My mom argued with my dad the whole time. I only got to talk to him for 10 seconds.”

Caregivers also expressed mixed feelings (i.e., both positive and ne = gative feelings) about children’s contact with incarcerated parents. Caregivers discussed challenges of maintaining contact, including distance to the prison, not having transportation, and the expense of telephone calls. One caregiver stated, “I would take the children to visit if I could. I’m doing the paperwork now so we can visit him.” Another caregiver cited the prison environment as a barrier to visitation, saying, “I don’t like exposing him to that.”

A common response regarding contact with the incarcerated parent involved the caregiver seeing herself as the child’s “protector” (expressing uncertainty about how to handle contact between the child and the incarcerated parent or being cognizant of potential difficulties that contact could have for the children, but not actively restricting contact). Although many caregivers wanted the child to have contact with the incarcerated parent, caregivers worried about the detrimental effects that contact might have on the child. One caregiver said, “It’s a tough situation. I don’t want to take them away from their dad, but sometimes dads aren’t good dads. I’m worried if I let them see him, what kinds of people they’ll grow up to be.” Several caregivers expressed feelings of disappointment with the incarcerated parent and a desire to protect the child from the parent’s poor decisions. One caregiver said, “I have mixed feelings. I want her to see her dad, but because of his bad habits, I don’t.”

Another theme that emerged concerned the caregiver as a “gatekeeper” of children’s contact with the incarcerated parent, which involved regulating or restricting children’s contact. In many cases, particularly with young children, caregivers controlled the child’s contact with the incarcerated parent by blocking telephone calls from the prison, refusing to accept collect calls, or limiting visits. One caregiver said, “I will only take the kids to visit if their father specifically requests that.” Several caregivers discussed children’s negative reactions as a result of contact with the imprisoned parent as one reason they had limited contact. One caregiver said that she stopped allowing the incarcerated parent to call, stating that “It only causes confusion and frustration for the child.”

In many cases, however, contact between the incarcerated parent and the child was facilitated by someone other than the child’s primary caregiver, bypassing the caregiver’s gate keeping role. In some cases, caregivers were unaware of these contacts. Most often a relative of the incarcerated parent was responsible for arranging contact between the child and the incarcerated parent, or children arranged contact on their own. One caregiver said, “I don’t know how often she speaks to her dad. If he calls, which is rare, he calls his family and then they 3-way call her so that she can talk to her dad.”

Quantitative analyses

At the intake interview, caregivers reported that most children (n = 40, 70%) had experienced some contact with their incarcerated parents through letters, phone calls, or visits prior to participation in the mentoring program. However, only seven children (12%) had experienced weekly contact, and many caregivers (n = 27, 47%) described contact as having been sporadic. Most children who continued to participate in the program for six months experienced some form of contact with the incarcerated parent (n = 22, 79%). However, only 21% (n = 6) of these children had a visit, letter, or call at least once per month. Few children experienced face-to-face visits across 6 months of program participation. Nearly half (n = 12, 43%) of the children did not visit, and only one child visited one or more times per month. Of the children who had contact with their incarcerated parent prior to the start of the program, most (86%) also had some contact (at least one visit, call, or letter) during the following six months. Further, among children who did not have any contact with their incarcerated parent prior to the start of the program, 29% continued to have no contact during the six months of the program.

We also examined whether children’s (age nine and older) feelings regarding their relationship with the incarcerated parent (IPPA-IP) at intake differed depending on whether they had contact with the imprisoned parent prior to program participation. Through a series of t-tests, we found that children who had experienced contact with their incarcerated parent before the start of the program reported fewer feelings of alienation and anger toward the parent at intake (M = 14.11, SD = 5.80) compared to children who had no contact (M = 19.50, SD = 4.89), t(22) = 2.20, p < .05. However, no differences emerged between groups regarding children’s feelings of trust, communication, or overall feelings about the incarcerated parent at intake. We did not make this comparison at six months because of the small number of children who completed the IPPA-IP at that time. Next, we conducted a series of t-tests to determine whether contact prior to or during program participation related to children’s averaged Internalizing and Externalizing scores at intake or 6 months. These analyses did not yield statistically significant differences, indicating that contact with the incarcerated parent was not associated with children’s problem behaviors.

The meaning and context of children’s behavior problems

Qualitative analyses

It was clear through interviews and teachers’ written responses that children’s behavior problems were a critical issue. Reports of fighting, bullying, arguing, and defiance were commonly reported during interviews. One caregiver said, “He blows up and gets really mad. He is defiant, smoking cigarettes and pot. He’s sexually active and stays out late, running the streets.” One teacher wrote, “Interactions with peers and adults have been very problematic – rude, dangerous, poor attitude, uncooperative.” Caregivers reported that children experienced problems at home (e.g., fighting with siblings, arguing with caregivers) and at school (e.g., detention, suspension, fighting with classmates). In addition, crying, withdrawal, fatigue, and developmental regressions were common. For example, one teacher described a child in her classroom as “distracted. She is extremely quiet and sad.” Another teacher wrote, “She cries for no apparent reason, isolates self from group.”

Teachers also emphasized children’s behavior problems and the challenges children experienced at home and school, especially with friendships and peers. When asked about what was most concerning about the child, one teacher wrote, “Her home life – no mom or dad, and grandma is not getting along with her daughter (child’s mom). She still focuses in class, but it makes her sad and volatile at times. She is impulsive and can feed off negative behaviors of others in the room.” Many teachers discussed children’s needs for extra attention and support, both at home and at school. For example, one teacher wrote, “She is extremely needy and you need to form a bond before you can get work or relationships. She will start out aggressive, but it’s just a big bark.” Another teacher wrote, “I am concerned about him getting appropriate attention at home among six siblings and four step-siblings. I am also concerned about the level of negative interactions between siblings.”

Several teachers were concerned about children’s relationships with peers, including themes related to self-confidence in relationships, trusting others, and neediness. One teacher wrote, “His self-esteem is low. He thinks he has no friends (which is not true), but he challenges his friendships by his inappropriate temper-type behaviors … He likes other children and desires their friendship but needs additional support in learning how to be friends appropriately.” Another teacher wrote, “She lacks confidence both academically and socially. She lashes out at others. She appears sad, anxious, and moody.”

Several participants discussed behavior problems that they directly attributed to social stigma associated with having an incarcerated parent. One child said, “I got in a fight on the bus. I beat the crap out of this kid because he was making fun of my [incarcerated] dad.” One caregiver said that her niece was often “teased at school because her mother is in prison.” Another caregiver discussed how the child had become disrespectful to teachers, attributing the change in behavior to the incarcerated parent’s upcoming release.

Quantitative analyses

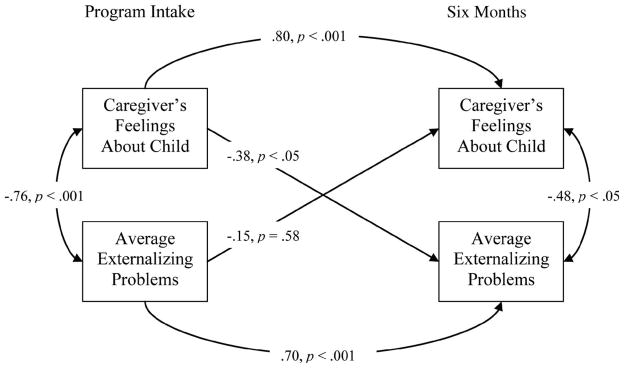

At intake, one-third of the children were rated as exhibiting borderline or clinically significant (T scores > 60) externalizing problems (n = 17, 33%), and 19% (n = 10) of children were rated as exhibiting borderline or clinically significant internalizing problems (on the basis of the averaged caregiver and teacher behavior checklist scores). For the 25 children who participated in the six month assessment, 32% (n = 8) of the children were rated as exhibiting borderline or clinically significant externalizing problems and 44% (n = 11) of children were rated as exhibiting borderline or clinically significant internalizing problems. At intake and six months, the rates of clinically significant internalizing and externalizing problems were higher than the 16% of children exhibiting internalizing and externalizing symptoms in the clinical range among normative samples (Achenbach, Howell, & Quay, 1991). Next, we examined links between children’s and caregivers’ perceptions and feelings about the caregiver–child relationship and children’s behavior problems over time. We assessed two cross-lag correlation models to examine associations between caregivers’ perceptions and feelings about children (R-IPA) and children’s averaged Internalizing and Externalizing scores across time. In both models, there was significant cross-time consistency in children’s behavior problems and caregivers’ relationship perceptions/feelings. In the Externalizing problems model, there was a significant association between intake R-IPA scores and six month Externalizing scores, suggesting that caregivers who felt more negatively about their relationships with children (they rated relationships with children seven years old and older) at the start of the program had children who were rated as engaging in more behavior problems six months later, controlling for the effects of children’s Externalizing problems at intake (see Figure 1). The Internalizing model was not significant, however. We did not interpret models focusing on children’s perceptions and feelings about caregivers or incarcerated parents because of the small number of IPPA’s completed at six months.

Figure 1.

Cross-lag correlation model for children’s externalizing problems (n = 19).

Stability of the caregiving environment

Quantitative analyses

Although themes specifically focusing on the importance of stability in the caregiving environment did not emerge in the children’s and caregivers’ interviews, we examined this issue because of its theoretical importance and previous findings focusing on children of incarcerated mothers (Poehlmann, 2005a). (Mentors, however, often noted the chaos and lack of stability in their descriptions of the families; see Shlafer et al., 2009.) In our sample, 13 (22%) children had changed caregivers prior to participating in the mentoring program. This change in living arrangements was more likely to have occurred in the eight instances in which the mother was incarcerated, χ2(1) = 22.12, p < .001, than when only the father was incarcerated. We compared children who changed caregivers with children from stable caregiving homes on children’s feelings about caregivers (IPPA-CG), incarcerated parents (IPPA-IP), and behavior problems using a series of t-tests. Results indicated that there were no group differences in children’s feelings about caregivers or behavior problems at intake as a function of the stability of the caregiving context.

Discussion

Using a mixed-method longitudinal design, the current study examined attachment and caregiving in relation to children’s contact with incarcerated parents, caregiving stability, and children’s behavior problems at home and at school in families affected by parental incarceration.

Children’s feelings about incarcerated parents

When directly asked about their perceptions and feelings about their incarcerated parents in interviews over time, 39% of children would not discuss their incarcerated parents. Of the children who were willing to discuss their incarcerated parents, 41% reported consistently positive perceptions and feelings about their relationships with incarcerated parents and 31% reported negative perceptions and feelings. For children age nine and older who completed the IPPA, their perceptions and feelings about caregivers and incarcerated parents did not differ overall, with only a trend level difference on the communication subscale. Because of such variability in perceptions and feelings across children, it is imperative for practitioners and researchers to refrain from making assumptions about whether or not a child experiences a sense of security in relation to that parent or even whether or not an incarcerated parent functions as an attachment figure for a child. It is important to determine the type and quality of relationships on a case by case basis.

Children’s contact with incarcerated parents

Consistent with national data (Glaze & Maruschak, 2008), most children in the present study had contact with their incarcerated parents through letters and phone calls, with rare or sporadic visitation. Most children expressed uncertainty about seeing the incarcerated parent and, although some children expressed excitement about an upcoming visit, none of those who discussed a recent visit reported having a positive experience. Interviews with children revealed the complexities of parent– child contact that would not have otherwise been revealed through quantitative measures assessing the frequency and type of contact. Future research in this area should utilize both methods in an effort to understand children’s contact with their incarcerated parents, as well as examining the association between quality of visits and children’s outcomes.

Quantitative analyses revealed that children who completed the IPPA (age nine and older) and who had one or more contacts with the incarcerated parent prior to program participation felt less anger and alienation toward the parent compared to children who experienced no contact, although feelings of trust and communication did not differ. These findings may reflect bidirectional influences as well as the quality of their relationships more broadly. Children who experience contact may feel less anger and alienation as a result of continued communication with their incarcerated parent compared to those who experience no contact. In addition, children with positive perceptions and feelings about the relationships may have more interest and motivation to see, call, or write to the parent and thus report more contact compared to children who have more negative perceptions and feelings. Our interviews revealed that contact with the incarcerated parent did not occur in some cases because of the child’s negative feelings about the incarcerated parent, in addition to caregivers’ preferences. In other cases, children reported feeling angry or upset because the incarcerated parent never called or wrote.

Previous studies that have documented positive effects of interventions designed to facilitate contact between children and incarcerated parents have typically focused on parents’ rather than children’s perceptions and attitudes, so effects of visitation on children are unclear. These effects may differ depending on factors such as the child’s age or the incarcerated parent’s gender. Poehlmann’s (2005a) findings linking recent visitation with representations of insecure attachment focused on young children, whereas Trice and Brewster’s (2004) report of positive effects of visitation focused on adolescents. Older children may have a better understanding of the situation and may be able to handle contact better than very young children, an issue that should be explored in future research.

Although contact with incarcerated parents was not related to ratings of children’s behavior problems at intake or six months later, some caregivers worried that children’s problematic behaviors increased following contact. Contact with an absent parent can activate a child’s attachment system (Poehlmann, 2003, 2005a), leading to increases in behaviors such as clinging, whining, and acting out. In many cases, these behaviors can be seen as communication strategies that indicate a child’s needs for comfort and for assistance with emotion regulation (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978; Bowlby, 1982).

Given these issues, it is not surprising that most caregivers expressed both positive and negative feelings about children’s contact with incarcerated parents, and many caregivers saw themselves as children’s “protectors,” consistent with the role of the caregiving behavioral system. Similar to previous research (Enos, 2001; Poehlmann, 2005c), many caregivers also restricted or controlled children’s contact with incarcerated parents, particularly when children were young or when the caregiver–incarcerated parent relationship was strained. Some of the caregivers in the present study were the incarcerated parents’ estranged partners; however, these issues arose even in cases in which a grandparent or other relative functioned as the child’s caregiver. Through interviews with children, we also found that some children had contact with incarcerated parents that was unregulated and sometimes undetected by caregivers. This was especially true for older children, who were less dependent on caregivers for the resources needed to maintain contact. Researchers and practitioners should consider children’s contact with incarcerated parents from a developmental perspective, and those who work in prison settings should take steps to improve the likelihood that a child’s visit with an incarcerated parent will be positive. This may include preparing family members for visits, working with incarcerated parents on communication and conflict resolution methods, improving settings in which visits occur (e.g., child-friendly rooms, no visits through Plexiglas), applying principles of attachment theory to recognize the effects of disrupted relationships on children and families, and assessing the effects of visitation from children’s perspectives.

Children’s behavior problems and family relationships

Consistent with their high risk status, children of incarcerated parents were rated as exhibiting behavior problems at higher rates than normative samples, and comments about behavior problems and challenges at school were pervasive. Most negative behaviors were expressed in a relational context, often in reaction to problems at home or with peers. Further, some caregivers reported that children exhibited behavior problems in response to the social stigma of having an incarcerated parent.

For children of incarcerated parents, as is the case for all children, caregivers provide a crucial context for children’s development (e.g., Cecil et al., 2008). This seems obvious to attachment scholars, but the vast majority of research and interventions focusing on families affected by parental incarceration has not included caregivers. In the present study, we examined caregivers’ (mostly biological mothers’) feelings about children and the stability of the caregiving environment in relation to children’s outcomes. We found that caregiving stability was less likely to occur when the mother was incarcerated (n = 8), a finding that is consistent with research suggesting that maternal incarceration creates a riskier situation for children than paternal incarceration (e.g., Dallaire, 2007). However, stability of caregiving was not related to perceived relationships or ratings of children’s behaviors in the quantitative analyses, in contrast to Poehlmann’s (2005a) study. Because of the discrepancy in these findings and the theoretical importance of disrupted caregiving for children, this issue should be examined in future research.

Children’s attachment relationships and corresponding internal working models have long-term implications for their social and emotional competence. Whereas securely attached children relate more positively to their peers and are described as competent, empathic, and self-confident (Bretherton & Munholland, 2008; Thompson, 2000), many children in our sample were described as rejecting their peers, lacking self-confidence, and doubting their friendships. Future research should consider how risks associated with parental incarceration affect children’s relationships not only within the family, but also within broader social networks, including teachers and peers. School personnel should recognize how parental incarceration can result in children feeling stigmatized and how this contributes to their difficult behaviors and challenges with peer relationships. Indeed, support and education offered in the school setting has been presented as a means of ameliorating some of these problems (Lopez & Bhat, 2007).

Our results also indicated that when caregivers reported less positive feelings about children at intake, children were rated as exhibiting more externalizing behavior problems at six months (controlling for intake externalizing problems). However, children’s initial behavior problems were unrelated to caregivers’ feelings about children at six months, controlling for caregivers’ initial feelings. The results of this analysis suggest a caregiver-to-child effect over time in families affected by parental incarceration, consistent with theoretical descriptions of the functions of a parent’s caregiving behavioral system (Bowlby, 1982). Similarly, Poehlmann, Park, and colleagues (2008) found that when children (half of whom had incarcerated mothers) living in custodial grandparent families exhibited more negative relationships with caregivers as measured with the ASCT, the children were rated by caregivers as exhibiting elevated rates of externalizing behavior problems. In addition, Mackintosh and colleagues (2006) found that children of incarcerated mothers rated themselves as engaging in fewer problem behaviors when they felt more warmth and acceptance from their caregivers. These findings suggest a need for exploring caregiving interventions to help children of incarcerated parents, rather than focusing exclusively on the child–incarcerated parent relationship (e.g., Cecil et al., 2008). In contrast to previous samples, most of the children in the current sample were being raised by their mothers and had experienced paternal incarceration. Although our sample of children with incarcerated mothers was too small to examine differences in children’s outcomes depending on which parent was incarcerated (similar to other studies, e.g., Murray & Farrington, 2005), this is an important area of inquiry for future research.

Study limitations

Our study has many limitations that should be noted when interpreting our findings. First, although our participation rate for the research was 100%, many families lived in poverty, moved frequently, or had disconnected telephones, and in two cases children ran away from home. In addition, data were collected in collaboration with a non-profit organization that had considerable staff turnover, minimal experience with evaluation research, and few resources to support evaluation. All of these factors resulted in attrition and substantial missing data, and at our six month assessment, few children and caregivers provided data (sample sizes ranged from 12 to 21). For these reasons, our ability to make full use of the longitudinal design was limited (e.g., we could not interpret cross-lag correlation models for IPPA scores or conduct analyses examining potential subgroup effects by gender). Because of missing data and early termination of mentoring relationships, we combined TRF and CBCL scores and thus were unable to examine teacher and caregiver reports of children’s behavior problems separately. Second, although the IPPA has been used with children in this age group, our study is among the first to use it with children of incarcerated parents. It is likely that this measure did not capture the complexity of the relationship between a child and an incarcerated parent, particularly across such a wide age range. However, in middle childhood and early adolescence, there is no “gold standard” for assessing attachment relationships. Our mixed-method approach allowed us to examine children’s feelings about the incarcerated parent through the IPPA and open-ended interviews, although other interviews (e.g., Attachment Interview for Children and Adolescents; Ammaniti, van IJzendoorn, Speranza, & Tambelli, 2000; Child Attachment Interview; Shmueli-Goetz, Target, Fonagy, & Datta, 2008) may be preferable for assessing children’s representations of relationships. Third, we were unable to interview incarcerated parents, who were imprisoned in multiple facilities within and outside the state. Finally, we did not examine the potential interaction between the developing mentor–child relationship and children’s feelings about their current caregivers or their incarcerated parents. Attachment theory suggests that mentors who provide long-lasting, consistent, and positive influences in children’s lives have the potential to change children’s internal working models and children’s feelings about their current and future relationships (Rhodes, Haight, & Briggs, 1999). Although this was beyond the scope of the current study, future research should consider how interventions such as mentoring have the potential to change children’s views of relationships and their attachment systems.

Because it is important to examine relationships from the perspectives of all family members, a strength of the study is that we included children’s views, which is rare in the literature focusing on parental incarceration. In addition, the mixed-method longitudinal design of this study and the number of interviews conducted (620 interviews across six months) are strengths, although additional longitudinal research with larger sample sizes is needed to examine the processes through which children’s relationships with caregivers, incarcerated parents, and peers affect their outcomes over time. We hope this study provides a starting point for more comprehensive studies in the future.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach T, Howell C, Quay HC. National survey of problems and competencies among four- to sixteen-year-olds: Parents’ reports for normative and clinical samples. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1991;56:1–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS. Some considerations regarding theory and assessment relevant to attachments beyond infancy. In: Greenberg MT, Cicchetti D, Cummings EM, editors. Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research, and intervention. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1990. pp. 463–488. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the Strange Situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Ammaniti M, van IJzendoorn MH, Speranza AM, Tambelli R. Internal working models of attachment during late childhood and early adolescence: An exploration of stability and change. Attachment & Human Development. 2000;2:328–346. doi: 10.1080/14616730010001587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armsden GC. Attachment to parents and peers in late adolescence: Relationships to affective status, self-esteem and coping with loss, threat and challenge. Dissertation Abstracts International. 1986;47:1751–1752. [Google Scholar]

- Armsden GC, Greenberg MT. The Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment: Relationships to well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1987;16:427–454. doi: 10.1007/BF02202939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armsden GC, McCauley E, Greenberg M. Parent and peer attachment in early adolescent depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1990;18:683–697. doi: 10.1007/BF01342754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Forty-four juvenile thieves: Their character and home life. International Journal of Psychoanalysis. 1944;25:19–53. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Separation. Vol. 2. New York: Basic Books; 1973. Attachment and loss. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Loss. Vol. 3. New York: Basic Books; 1980. Attachment and loss. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss. 2. Vol. 1. New York: Basic Books; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Brack G, Gay MF, Matheny KB. Relationships between attachment and coping resources among late adolescents. Journal of College Student Development. 1993;34:212–215. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I, Munholland K. Internal working models in attachment relationships: Elaborating a central construct in attachment theory. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 89–114. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton I, Ridgeway D, Cassidy J. Assessing internal working models of the attachment relationship: An attachment story completion task for 3-year-olds. In: Greenberg MT, Cicchetti D, Cummings EM, editors. Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research, and intervention. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1990. pp. 273–308. [Google Scholar]

- Cecil DK, McHale J, Strozier A, Pietsch J. Female inmates, family caregivers, and young children’s adjustment: A research agenda and implications for corrections programming. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2008;36:513–521. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL, Guttmann ML, Hanson WE. Advanced mixed methods research designs. In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie CB, editors. Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. pp. 209–240. [Google Scholar]

- Dallaire DH. Children with incarcerated mothers: Developmental outcomes, special challenges, and recommendations. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2007;28:15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Enos S. Mothering from the inside: Parenting in a woman’s prison. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- George C, Solomon J. The caregiving system: A behavioral systems approach to parenting. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 833–856. [Google Scholar]

- Glaze L, Maruschak L. US Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report. 2008. Parents in prison and their minor children; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Health and Human Services Poverty Guidelines, 70 Fed. Reg. 8373. 2005 Retrieved 16 November 2009, from http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/05poverty.shtml.

- Johnson LN, Ketring SA, Abshire C. The Revised Inventory of Parent Attachment: Measuring attachment in families. Contemporary Family Therapy: An International Journal. 2003;25:333–349. [Google Scholar]

- Kobak R, Madsen S. Disruptions in attachment bonds: Implications for theory, research, and clinical intervention. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Larose S, Boivin M. Structural relations among attachment working models of parents, general and specific support expectations, and personal adjustment in late adolescence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1997;14:579–601. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez C, Bhat CS. Supporting students with incarcerated parents in schools: A group intervention. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work. 2007;32:139–153. [Google Scholar]

- Mackintosh VH, Myers BJ, Kennon SS. Children of incarcerated mothers and their caregivers: Factors affecting the quality of their relationship. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2006;15:581–596. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus RF, Betzer PD. Attachment and antisocial behavior in early adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1996;16:229–248. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy CJ, Moller NP, Fouladi RT. Continued attachment to parents: Its relationship to affect regulation and perceived stress among college students. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development. 2001;33:198–213. [Google Scholar]

- Mumola CJ. Special report: Incarcerated parents and their children. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Murray J, Farrington DP. Parental imprisonment: Effects on boys’ antisocial behaviour and delinquency through the life course. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:1269–1278. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray J, Farrington DP. The effects of parental imprisonment on children. In: Tonry M, editor. Crime and justice: A review of research. Vol. 37. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2008a. pp. 133–206. [Google Scholar]

- Murray J, Farrington DP. Parental imprisonment: Long-lasting effects on boys’ internalizing problems through the life course. Development and Psychopathology. 2008b;20:273–290. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray J, Janson CG, Farrington DP. Crime in adult offspring of prisoners: A cross-national comparison of two longitudinal samples. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2007;34:133–149. [Google Scholar]

- Myers BJ, Smarsh TM, Amlund-Hagan K. Children of incarcerated mothers. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1999;8:11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Papini DR, Roggman LA. Adolescent perceived attachment to parents in relation to competence, depression, and anxiety: A longitudinal study. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1992;12:420–440. [Google Scholar]

- Papini DR, Roggman LA, Anderson J. Early-adolescent perceptions of attachment to mother and father: A test of emotional-distancing and buffering hypotheses. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1991;11:258–275. [Google Scholar]

- Poehlmann J. An attachment perspective on grandparents raising their very young grandchildren: Implications for intervention and research. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2003;24:149–173. [Google Scholar]

- Poehlmann J. Representations of attachment relationships in children of incarcerated mothers. Child Development. 2005a;76:679–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poehlmann J. Children’s family environments and intellectual outcomes during maternal incarceration. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005b;67:1275–1285. [Google Scholar]

- Poehlmann J. Incarcerated mothers’ contact with children, perceived family relationships, and depressive symptoms. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005c;19:350–357. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.3.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poehlmann J, Park J, Bouffiou L, Abrahams J, Shlafer R, Hahn E. Attachment representations in children raised by their grandparents. Attachment & Human Development. 2008;10:165–188. doi: 10.1080/14616730802113695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poehlmann J, Shlafer RJ, Maes E, Hanneman A. Factors associated with young children’s opportunities for maintaining family relationships during maternal incarceration. Family Relations. 2008;57:267–280. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes JE, Haight WL, Briggs EC. The influence of mentoring on the peer relationships of foster youth in relative and nonrelative care. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1999;9(2):185–201. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson J. Some responses of young children to the loss of maternal care. Nursing Times. 1953;49:382–386. [Google Scholar]

- Shlafer R, Poehlmann J, Coffino B, Hanneman A. Mentoring children with incarcerated parents: Implications for research, practice, and policy. Family Relations. 2009;58:507–519. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2009.00571.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmueli-Goetz Y, Target M, Fonagy P, Datta A. The child attachment interview: A psychometric study of reliability and discriminant validity. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(4):939–956. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder ZK, Carlo TA, Mullins MM. Parenting from prison: An examination of children’s visitation program at a women’s correctional facility. Marriage and Family Review. 2001;32:33–61. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Grounded theory in practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA. The legacy of early attachments. Child Development. 2000;71:145–152. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tierney JP, Grossman JB, Resch N. Making a difference: An impact study of Big Brothers/Big Sisters (re-issue 1995 study) Philadelphia, PA: Public/Private Ventures; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Trice AD, Brewster J. The effects of maternal incarceration on adolescent children. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology. 2004;19:27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Tuerk EH, Loper AB. Contact between incarcerated mothers and their children: Assessing parenting stress. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 2006;43:23–43. [Google Scholar]