Abstract

Phagocytosis can be induced via the engagement of Fcγ receptors by antibody-opsonized material. Furthermore, the efficiency of antibody-induced effector functions has been shown to be dramatically modulated by changes in antibody glycosylation. Because infection can modulate antibody glycans, which in turn modulate antibody functions, assays capable of determining the induction of effector functions rather than neutralization or titer provide a valuable opportunity to more fully characterize the quality of the adaptive immune response. Here we describe a robust and high-throughput flow cytometric assay to define the phagocytic activity of antigen-specific antibodies from clinical samples. This assay employs a monocytic cell line that expresses numerous Fc receptors: including inhibitory and activating, and high and low affinity receptors—allowing complex phenotypes to be studied. We demonstrate the adaptability of this high-throughput, flow-based assay to measure antigen-specific antibody-mediated phagocytosis against an array of viruses, including influenza, HIV, and dengue. The phagocytosis assay format further allows for simultaneous analysis of cytokine release, as well as determination of the role of specific Fcγ-receptor subtypes, making it a highly useful system for parsing differences in the ability of clinical and vaccine induced antibody samples to recruit this critical effector function.

Keywords: Phagocytosis, Antibody, ADCC, antibody-dependent phagocytosis, monocytes, Fc receptor, effector function

1. Introduction

Antibodies are potent determinants of the humoral immune response. Though generated as a result of the interaction of B and T cells, antibodies trigger their cytotoxic effects by interacting with complement and innate effector cells. Thus they provide a functional link between the adaptive and innate immune system. They consist of two identical variable domains (Fv) capable of recognizing a target antigen, and a single constant domain (Fc) capable of interacting with the effector cells of the immune system. Traditionally, the epitope recognized by the Fv domains has been thought to be of paramount importance, in that binding to some epitopes can block, or neutralize the native function of the cognate antigen. However, the neutralizing activity mediated by the Fv domains of these antibodies has been found to be insufficient for their protective effects in numerous settings(Clynes et al., 2000; Johnson and Glennie, 2003; Schmidt and Gessner, 2005; Hessell et al., 2007), and evidence of the importance of the constant domain's effector function in clinical outcomes has been accumulating across fields ranging from cancer immunotherapy(Dall'Ozzo et al., 2004) to autoimmunity(Laszlo et al., 1986) and chronic viral infection(Shore et al., 1974). Analogously to the Fv escape mechanisms such as mutating surface epitopes, several pathogens evade the Fc-mediated antibody response by expressing proteases that restrict the Fc domain(Shakirova et al., 1985; Berasain et al., 2000; Collin et al., 2002; Vidarsson et al., 2005; Aslam et al., 2008), or glycosidases that remove the sugar residues required for interaction with Fc receptors(Allhorn et al., 2008). Combined, these evasion mechanisms and clinical correlates provide strong evidence as to the importance of Fc-based effector functions in the therapeutic activity of antibodies.

Significantly, while the primary sequence of the constant domain is conserved across antibodies of a given isotype, the effector functions of distinct antibody isotypes are profoundly modulated by alterations in the glycosylation profile at asparagine 297 (Asn297) in the CH2 domain of the antibody, modulating the range of effector responses a given antibody may elicit(Boyd et al., 1995). The presence or absence of particular sugar groups on the Fc domain tunes the affinity between IgG and Fc receptors (FcγRs) on effector cells, and Fc glycoform represents a potent means of modulating antibody activity(Lund et al., 1996; Raju, 2008). This modulation is bidirectional, as some sugar structures dramatically affect affinity to stimulatory FcRs, while others are known to inhibit immune activation(Shields et al., 2002; Kaneko et al., 2006; Nimmerjahn et al., 2007; Scallon et al., 2007; Raju, 2008; Anthony and Ravetch, 2010).

Similarly, the expression levels of FcγR are also able to modulate antibody activity. Among IgG binding FcRs, multiple isoforms with distinct functions have been identified: FcγgR1 (high affinity, activating), FcγR2a (low affinity, activating), FcγR2b (low affinity, inhibitory), and FcγR3 (low affinity, activating). Thus, FcRs for IgG antibodies include both high and low affinity, as well as activating and inhibitory receptors, each of which may have differential affinities for various IgG glycoforms, and may be expressed at different levels on different cell types. Thus, FcγR expression levels combined with Fc glycosylation patterns represent a highly tunable system for modulating the activity of antibodies.

While numerous classes of innate immune cells express the FcγR involved in antibody-mediated cytotoxicity, a subset of these are capable of acting as professional phagocytes, including monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells, and mast cells. Phagocytic mechanisms have a demonstrated importance in clearance, antigen presentation, and innate immune activation. Additionally, antibody-driven phagocytosis enhances infection in several infectious diseases(Halstead and O'Rourke, 1977; Marchette et al., 1979; Bernard et al., 1990; Tamura et al., 1991; Fust et al., 1994; Kozlowski et al., 1995) indicating a relevance of phagocytic processes not only on protection from, but in susceptibility to disease, and highlights the significance of this effector function in particular.

Overall, as a potent mechanism of antibody-mediated effector function, antibody-dependent phagocytosis of immune complexes, opsonized pathogens, and host cells represents an important connection between the adaptive and innate immune systems. Because antibody glycosylation patterns and therefore FcR affinity, and immune activity differ, a robust means to measure this critical effector function may help define qualitative differences in this effector function during infection, and post-vaccination that may play an important role in protection. Here we present a high throughput assay capable of measuring the phagocytic activity of antibodies in clinical samples.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Cells, control antibodies, viral envelope antigens

THP-1 cells were purchased from ATCC and cultured as recommended. Care was taken to keep cultures at cell densities below 0.5×106/ml in order to maintain consistent levels of FcγR expression and assay performance.

A panel of antibodies to FcγR 1, 2, 2A, 2B, and 3 was used (BD Pharmingen, 558592, 555406; Biolegend, 303212; Novus Biologicals, NB100-79947; RD Systems, AF1875) to determine receptor expression on THP-1 cells. Quantum Simply Cellular bead standards (Bangs Laboratories, 815) were used to quantify the number of these receptors on THP-1 cells according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Flu hemagglutinin (Sino Biological, 11085-V08H), dengue-2 E peptide (ProsecBio, DEN-006) and gp120 (Immune Technology, IT-001-0027p YU-2) were biotinylated on lysine residues using a sulfo-NHS LC biotin reagent (Thermo Scientific, 21935) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After the reaction, free biotin was removed by extensive buffer exchange using Amicon centrifugal concentration units of appropriate molecular weight cutoff.

2.2 Phagocytosis Assay

Biotinylated antigen was incubated with 1 μm fluorescent neutravidin beads (Invitrogen, F8776) overnight at 4°C. Beads were subsequently spun down and washed twice in PBS-BSA in order to remove excess unbound antigen, and then resuspended at a final dilution of 1:100 in PBS-BSA. Antigen-coated beads were stored for up to a week at 4°C prior to use. Saturation of the beads was determined experimentally, via incubation with differing amounts of antigen. Bead coating conditions that gave the maximal phagocytic score in conjunction with a control monoclonal antibody were used. 9×105 beads (equivalent of 0.1 μl of supplied suspension, or 10 μl of the dilution described above) were placed in each well of round bottom 96 well plate. Antibodies were added to each well and the plate was incubated for a 2 hours at 37°C in order to allow antibodies to bind to the beads. Following equilibration, 2×104 THP-1 cells were added to each well in a final volume of 200 μl, and the plate was incubated overnight under standard tissue culture conditions. The next day, half the culture volume was removed, saved for subsequent multiplexed analysis of cytokine secretion, and replaced with 100 μl of 4% paraformaldehyde before plates were analyzed by flow cytometry on a BD LSR II equipped with an HTS plate reader. Samples were mixed thoroughly (100 μl mix volume, repeated three times), prior to analysis of 30 μl of each sample, yielding at least 2,000 cell events per sample. A phagocytic score was determined by gating the samples on events representing cells, and calculated as follows: (% bead positive × MFI bead positive, or integrated MFI(Darrah et al., 2007)). For ease of presentation, these scores were then divided by 106. Alternatively, because the first peak of bead-positive cells represents cells that have phagocytosed a single bead, it is possible to use the MFI of this peak to determine the average number of beads phagocytosed by each cell, with the added advantage of removing instrument variability from the data generated. Error bars represent standard deviations of at least 3 replicates.

2.3 Confocal and video microscopy

For experiments involving imaging of the THP-1 cells, 1.2×106 cells were incubated with 9×106 beads (equivalent to 1 μl of supplied suspension) saturated with biotinylated human IgG, or left uncoated in a 3 ml volume in a 12 well plate overnight at either 4°C, or under standard tissue culture conditions. Cultures were resuspended, 1.5 mls was withdrawn, spun down, aspirated, and fixed with paraformaldehyde. Following fixation, cells were again spun down, aspirated, and resuspended in 500 μl of 300 mM sucrose in phosphate buffered saline. The cell membrane was stained by addition of 5 μl DiI (Invitrogen, V22885) and incubation at 37°C for 10 minutes. Stained cells were washed twice before being dropped onto a poly-L-lysine-coated microscope slide, and then imaged on a Zeiss LSM 510 microscope at 63× magnification, Zeiss Plan-Apochromat DIC, 1.4NA, oil immersion lens. Microscopy conditions were set such that optical sections were not thicker than the bead diameter. Additionally, 3-dimensional stacks were collected in order to confirm the internalization profile of bead particles.

Time-lapse images of phagocytosis were acquired on a Zeiss Axio Observer at 20× magnification on a Zeiss Axio Observer using a Zeiss Plan-Apochromat, air, 0.8NA lens over a 14-hour period at a rate of 1 image per minute. Seventy thousand THP-1 cells were combined with a 30-fold excess of uncoated, red fluorescent beads, and a 30-fold excess of antibody-coated, green fluorescent beads, and spun down through a collagen matrix at 2,000 rpm onto a coverslip chamber (LabTek, 177402) coated with fibronectin to aid with cell adherence. At the conclusion of the 14-hour imaging period, a 63× Zeiss Plan-Apochromat 1.4NA oil immersion lens was used to capture representative images at higher magnification. Image acquisition and analysis was performed using Metamorph software (Molecular Devices).

2.4 Amnis ImageStreamX Flow Cytometry

Cells were prepared as described for the phagocytosis assay with the addition of an anti- FcγR2-Alexa647 antibody to label FcγR2, and DAPI to label nuclei, and run on an Amnis ImageStreamX flow cytometer with 60× magnification. Samples were analyzed with the IDEAS software platform in order to determine an internalization score. Briefly, a mask representing the cell membrane was defined by the brightfield image, and an internal mask was defined by eroding the whole cell mask by 6 pixels, resulting in an area significantly smaller the cell membrane. An internalization score was calculated as follows: (number of fluorescent pixels in internal mask) – (number of fluorescent pixels in the entire field of view).

2.5 Control antibodies and deglycosylation reaction

Human IgG (Sigma, I2511) was biotinylated on lysine residues using a sulfo-NHS LC biotin reagent (Thermo Scientific, 21935) as described previously. A fraction of the biotinylated antibody was subsequently deglycosylated using PNGase F (NEB, P0704) according to the manufacturer's instructions. B12, lala B12, and double and triple mutant B12 were obtained from Dennis Burton. The anti-dengue antibody 3H5 was purchased from Millipore (Millipore, MAB10226).

2.6 Receptor Blocking Experiments

Receptor blocking antibodies to FcγR2 (Abcam, 23336) and FcγR3 (Sigma, F3668) were used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were preincubated with blocking antibodies for at least 1 hour prior to being mixed with beads, incubated overnight, and then analyzed by flow cytometry. Because the blocking antibodies do not necessarily block all receptor function under the conditions tested, results are presented as the ratio of phagocytic activity of triple: double mutant for each blocking antibody condition, rather than compared to untreated controls.

2.7 Patient antibodies

Study individuals were recruited from Ragon Institute cohorts and included patients with influenza infection, chronically HIV infected individuals, and healthy individuals. Antibodies were separated from other serum proteins using Melon Gel according to the manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Scientific, 45206). The study was approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Institutional Review Board, and each subject gave written informed consent. The anti-dengue 2 antibody, 3H5 (Millipore, MAB10226), a mouse isotype capable of interacting with human FcγR2(Littaua et al., 1990; Flesch et al., 1997) was used a positive control for dengue-coated beads.

2.8 Luminex Assays

Milliplex cytokine analysis was performed on the Luminex xMap platform following the manufacturer's instructions (Millipore, custom kit) on supernatants removed from phagocytosis assay plates.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 The phagocytosis assay

In addition to their role in neutralization, antibodies are able to mediate a number of additional functions including the recruitment of innate immune responses to eliminate antibody-opsonized material. Among these additional antibody mediated functions, antibodies are able to promote phagocytosis, which may play a profound role in the rapid containment and clearance of a pathogen following infection. However, robust assays that are able to capture differences in the quality of antibody-mediated phagocytosis are lacking. Thus to this end we developed a novel high-throughput assay, using a monocytic-cell line to provide a platform to tease out antigen-specific antibody mediated phagocytosis. Briefly, the antibodies of interest are captured on the surface of highly fluorescent latex beads, which are then incubated overnight with monocytes prior to analysis by flow cytometry. Because the beads used may be coated with an antigen of choice, this assay allows determination of antigen-specific phagocytosis without requiring purification of these antibodies.

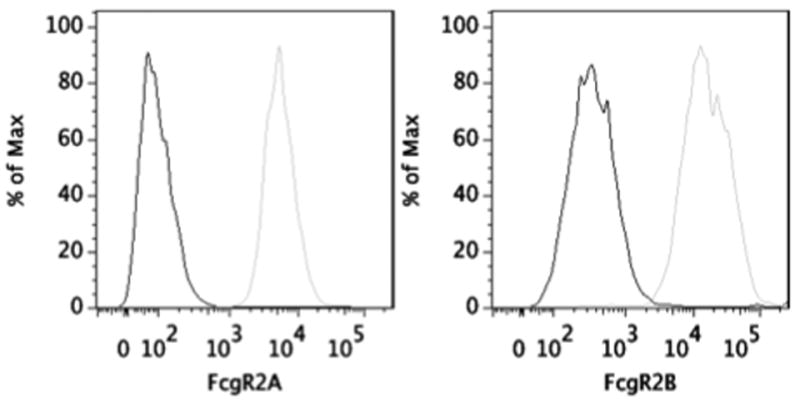

We employed a widely used monocytic cell line, THP-1(Tsuchiya et al., 1980), which have been extensively used in studies of phagocytosis of particles including red blood cells, yeast(Tsuchiya et al., 1982), e.coli(Schiff et al., 1997), staphylococcus(Kapetanovic et al., 2007), zymosan(Friedland et al., 1993a), and human cells(Tebo et al., 2002; Beum et al., 2008). They have also been utilized in studies of signaling downstream of phagocytosis, including cytokine release(Shaw et al., 2000), oxidative burst(Gross et al., 1998), and receptor phosphorylation(Lee et al., 2007). Moreover because they grow in suspension, they are an convenient choice for use in a flow cytometry-based assay. Additionally, much is known about modulation of FcγR expression and maturation in this cell line upon treatment with various stimulants and cytokines(Fleit and Kobasiuk, 1991). Importantly, as demonstrated in table 1, THP-1 cells express multiple Fcγ receptors, including FcγR1, FcγR2, and FcγR3, allowing this cell line to capture effects from a broad range of FcγRs, and reflecting the normal FcγR2 expression profile of monocytes (data not shown). Significantly, these cells also express both subtypes of FcγR2: the activating receptor implicated in phagocytosis, 2A, and the inhibitory, ITIM motif-containing 2B receptor (Figure 1). When quantified, we found that FcγR2 is expressed at significantly higher levels than the other FcγR. While the phagocytic properties of THP-1 cells are increased upon exposure to stimulants such as PMA(Tsuchiya et al., 1982), these treatments tend to stimulate non-Fc-dependent phagocytic processes, and can alter FcγR expression profiles (data not shown). Because they therefore tend to increase baseline phagocytosis levels, and thereby decrease the relative signal change due to antibody-dependent phagocytosis, the assay we describe does not utilize any chemical stimulants to mature the THP-1 cells.

Table 1. FcγR quantification on THP-1 cells.

FcgR receptors were quantified using bead standards.

| FcgR | Number of Receptors | +/- SD |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 66,300 | 15,000 |

| 2 | 171,000 | 13,000 |

| 3 | 18,000 | 1,600 |

Figure 1. Expression of FcγR2A and 2B.

THP-1 cells were labeled with antibodies specific for the extracellular domain of FcγR2A, the Fc receptor implicated in phagocytosis, and the intracellular domain of the inhibitory receptor FcγR2B. Cells labeled with secondary only are traced in black, cells labeled with primary and secondary antibody are traced in gray.

Antibodies are captured on the surface of 1.0 um fluorescent microspheres in a 96-well plate. After incubation at 37°C for at least an hour to allow opsonization to occur, 20,000 THP-1 cells in 200 ul of media are added to each well, and allowed to phagocytose the antibody-coated microspheres overnight at 37°C. The following day, plates were spun down, and half of the sample volume is replaced with 4% paraformaldehyde for fixation. Samples were then run on a BD LSRII cytometer equipped with a high-throughput sampler. Because the microspheres are exceptionally bright, care was taken in determining acquisition settings in order to ensure both bead-positive and bead-negative populations were within the dynamic range of the instrument. To provide a convenient quantitative measure of net phagocytosis, a phagocytic score was calculated by determining the percentage of cells that were bead-positive, and multiplying by their mean fluorescence intensity (iMFI)(Darrah et al., 2007).

Preliminary experiments were carried out using biotinylated bulk human IgG which was trapped directly on the surface of neutravidin-coated beads. A range of cell (20,000 to 100,000) and bead (9×105 to 9×106) concentrations were evaluated, and the ratio of 45 beads per cell, with 20,000 cells used per well was selected because it yielded the greatest signal change between antibody coated and non-coated beads. While a value of 15 particles per phagocytic cell might be a more typical ratio, because our assay format utilizes suspension cells and does not call for centrifugation to confine beads and cells to a 2-dimensional plane at the start of the experiment, we have found that a greater particle to cell ratio and a longer incubation time is optimal.

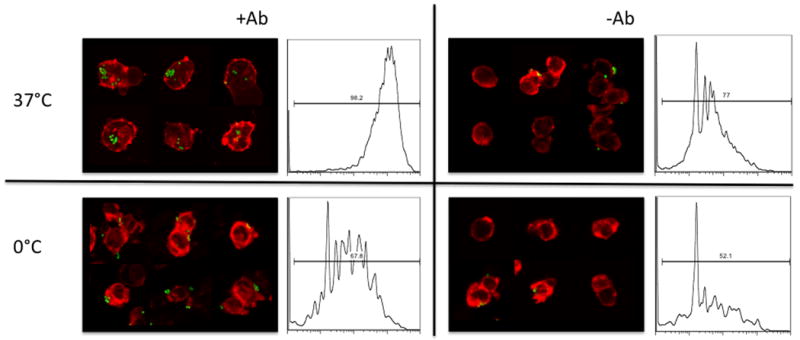

3.2 Microscopy confirmation of phagocytosis

In order to demonstrate that the beads were in fact phagocytosed, and did not simply associate with the cell membranes, internalization of the beads was confirmed by confocal microscopy. Figure 2 presents confocal microscopy images and corresponding flow cytometry histograms of the phagocytosis of green fluorescent microspheres under various conditions. Bead uptake, as determined by fluorescence in the flow cytometry readout was maximal when cells were incubated with antibody-coated beads at 37°C. In contrast, at 0°C, phagocytosis is impaired, but antibody-coated beads still associate with cells due to specific interactions between antibodies on the beads and FcγR on the cells, leading to a lower signal on FACS histograms, and the appearance of surface-associated rather than phagocytosed beads by confocal microscopy. While FACS signals from uncoated beads at both temperatures are significantly lower, they are not zero, as the latex beads tend to associate non-specifically. This level of fluorescence represents a negative control in the evaluation of experimental samples.

Figure 2. Phagocytosis Assay.

Confocal microscopy images and flow cytometry histograms of phagocytosis of green fluorescent beads with or without antibody coating, at 37°C or 0°C. For confocal microscopy, membrane was stained red with the membrane dye, DiI. Histograms represent the fluorescent signal from cell-associated beads. Bead uptake is maximal under conditions where FcγR-mediated phagocytosis can occur.

As a second means to verify the internalization of the presumptively phagocytosed beads, the Amnis ImageStream × imaging flow cytometer, which captures an image of each cell as it passes through the stream, offers a unique opportunity to perform statistical analysis of bead internalization on a large number of imaged cells, which is not possible with traditional confocal microscopy. For these experiments, cell nuclei were stained with DAPI, and FcγR2 was stained with an APC-conjugated antibody. Figure 3A presents cells that were assessed as bead negative (top), surface-bound bead positive (middle), and internalized bead positive (bottom). Interestingly, the internalized beads cluster with FcγR2, in some cases, suggesting that this FcγR may be implicated directly in phagocytosis. Amnis-collected images were analyzed using the IDEAS software package in order to determine internalization scores of the beads associated with cells under various conditions. Internalization scores were calculated by generating a mask representing the membrane of the cell as generated from the brightfield image, and then subtracting 6 pixels, yielding an internal mask which results in an area significantly smaller than the cell membrane. The fraction of fluorescent pixels in the bead channel assigned to locations within the internal mask was calculated as a ratio of pixels inside versus outside the internal mask. Figure 3B presents the internalization scores of cells incubated with bare or antibody-coated beads at 0°C and 37°C, and demonstrates that only under conditions in which antibody-dependent phagocytosis can occur (opsonized, 37°C) were samples scored as having internalized beads—confirming that our flow based assay captures internalization rather than simple surface association.

Figure 3. Confirmation of phagocytosis.

A. Representative images captured by the Amnis ImageStreamX Flow Cytometer of cells without any beads (top), surface bound beads (middle), or internalized beads (bottom). Nuclei are stained blue, beads green, and FcγR2 in red. B. Internalization score calculated by Amnis' IDEAS software, indicating internalization of beads when coated by antibody at 37°C, and minimal internalization of beads without antibody-coating, or when incubated at 0°C. C. Dependence of phagocytic score on the density of antibody coating on the surface of the beads.

3.3 Defining parameters affecting phagocytosis

As a further means to quantitatively demonstrate that the phagocytosis observed is dependent on the presence of antibody, Figure 3C presents an antibody density dose-response curve. Beads were incubated with decreasing amounts of antibody, yielding decreasing phagocytic signal. Similarly, if the antigen density on the beads is decreased but antibody quantities are maintained, a similar dose-response curve is observed (data not shown), suggesting that antibody mediated phagocytosis is directly related to both the frequency of antibody-opsonized targets, but also that the level of phagocytosis can be enhanced in the presence of increasing quantities of bound antibodies.

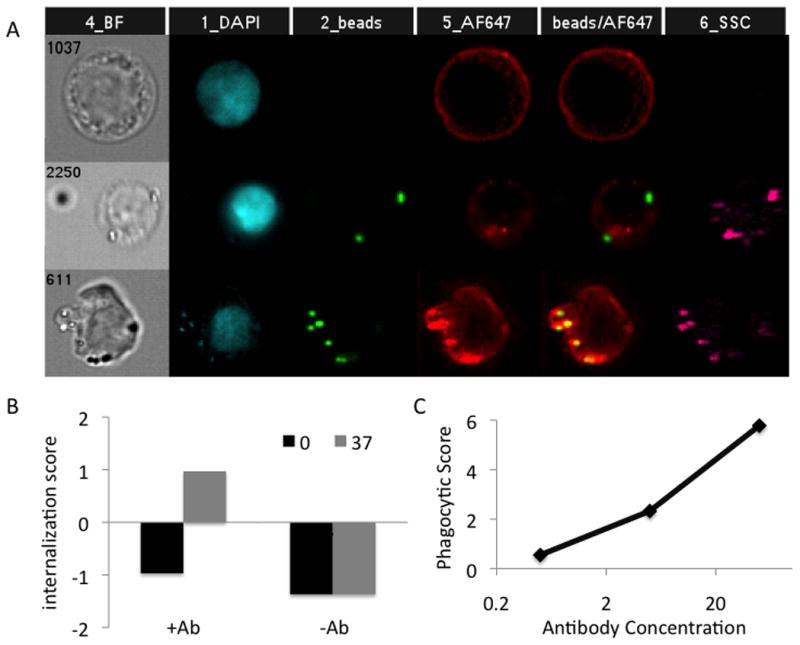

Because the interaction between antibodies and FcγR is highly dependent on the glycosylation state at Asn297 on the Fc domain(Yamaguchi et al., 2006), we next aimed to determine whether our flow based antibody-mediated phagocytosis assay was equally dependent on the presence of the antibody glycan. Thus antibodies were deglycosylated using the broad glycosidase, PNGaseF, and tested in the phagocytosis assay. In fact, the resulting cleavage between the innermost GlcNAc and asparagine residues of high mannose, hybrid, and complex oligosaccharides from the N-linked glycosylation site in the Fc domain of the antibodies ablated phagocytosis, as shown in Figure 4A,B. As a control, equivalent function of the Fv domains after deglycosylation was experimentally verified by measuring equivalent antibody binding to beads treated with antibody before and after deglycosylation (data not shown). Thus overall these data suggest that this assay is able to also read out differences in phagocytic potential due to the glycan.

Figure 4. Dependence on antibody glycosylation state.

A. Phagocytic scores and B. Flow cytometry histograms depicting cells incubated with uncoated (-Ab), antibody-coated (+Ab), and deglycosylated antibody-coated (+deglycosylated Ab) fluorescent beads. Uptake of antibody-coated beads is highly dependent on antibody glycosylation state.

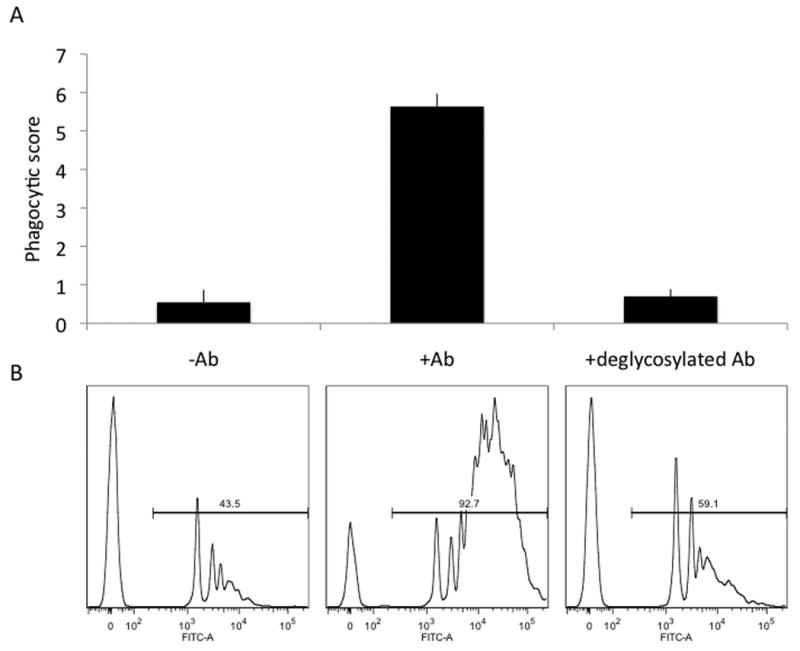

3.4 Detection of functional consequences to changes in the Fc domain of recombinant IgG

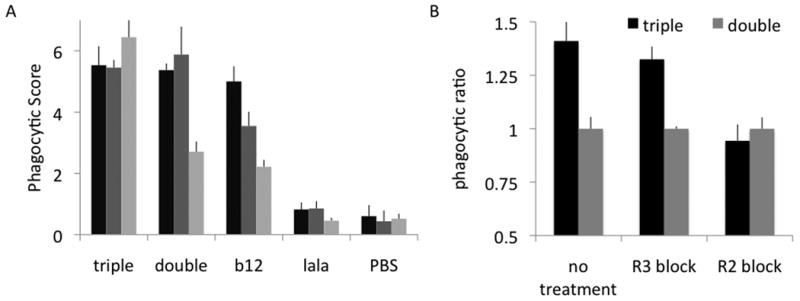

Next, in order to isolate the phagocytic potential of antigen-specific, rather than bulk antibodies, gp120, HIV antigen-coated beads were opsonized with antigen-specific monoclonals to recruit phagocytosis. As a negative control, HIV antibodies directed at antigens other than gp120 were tested and showed only background phagocytic levels against gp120-coated beads (data not shown). To test both antigen specificity and Fc-domain activity, a series of Fc domain mutants (Shields et al., 2001; Hessell et al., 2007) of B12, an antibody that recognizes HIV gp120 envelope protein, were investigated. Importantly, the variable domains of each of these antibody variants are identical, and therefore differences observed in the phagocytic profile of each are due solely to the alterations in their Fc domains. Double mutant (S239D/I332E) and triple mutant (S239D/I332E/G236A) B12, which have improved binding to FcγR 1, 2A, 2B, and 3A relative to wildtype Fc domains (Shields et al., 2001; Richards et al., 2008) were compared to standard B12, lala B12 (a non FcγR-binding variant), and a PBS control (Figure 5A). As expected, the non-binding lala variant demonstrated only background levels (equivalent to PBS control) of phagocytosis at a range of concentrations, while standard B12 demonstrated high phagocytic scores. Triple and double mutants gave improved phagocytic scores at low concentrations relative to standard B12, in agreement with their increasing affinity to FcγRs. These data therefore demonstrate that this phagocytic assay is strongly modulated by Fc: FcγR affinity, and may be a useful tool for defining the carbohydrate alterations that may modulate the capacity of a given antibody to recruit phagocytosis.

Figure 5. Dependence on specific FcγR.

A. gp120-coated beads were incubated with b12 variants triple, double, standard and lala (Fc binding knockout) at varying concentrations (100, 20, 5 ng/ml), and the phagocytic score was determined. B. Receptor blocking experiments in which either FcγR2 or FcγR3 was blocked by preincubation with an anti- FcγR antibody. Results are presented as the ratio of the phagocytic score for the variant:double mutant at each given condition.

3.5 Determining the role of specific FcγR in phagocytosis

Given that THP-1 cells express an array of FcγRs, this assay also provides an opportunity to tease out the dependence of antibody-mediated phagocytosis on specific FcγR subtypes in experiments utilizing receptor-blocking antibodies. Cells were preincubated with blocking antibodies against either FcγR2 (recognizing both 2A and 2B), and FcγR3, and phagocytic scores were compared to no blocking antibody treatment. While receptor blocking experiments frequently indicate that blocking FcγR2 decreases phagocytosis, combinations of receptor-blocking antibodies are more effective, indicating that multiple receptors play a role in phagocytic processes(Richards et al., 2008). Accordingly these data suggest that this assay may also permit the evaluation of multiple FcγR subclass interactions.

A pair of Fc domain point mutants of B12, double mutant (S239D/I332E) and triple mutant (S239D/I332E/G236A), with improved binding to FcγR1, 2A, 2B, and 3A relative to wildtype Fc domains were tested(Shields et al., 2001; Richards et al., 2008). The additional point mutation in the triple mutant has been reported to increase antibody affinity to FcγR2A—imparting specificity to the activating (2A) rather than inhibitory (2B) receptor. Indeed, the triple mutant was observed to have an improved phagocytic profile relative to the double mutant, as shown in Figure 5A. As would be expected because their binding to FcγR3A is equivalent, when this receptor is blocked, the triple mutant still outperforms the double mutant (Figure 5B). However, when FcγR2 is blocked, the phagocytic activity of the triple mutant is reduced to equivalence with the double mutant, confirming again that this assay is a reliable readout of known Fc-related activities.

Interestingly, we have also observed that at high concentrations of antibody, phagocytosis is reduced (data not shown). This profile reflects the Hook or prozone effect, in which antibodies exhibit paradoxical activity patterns at high concencentrations(Taborda et al., 2003). This decrease might be due to free antibody occupying FcγRs on the THP-1 cells and thereby competing with binding of opsonized particles, as these decreases are observed at concentrations similar to the Kd of interactions with FcγR2 and 3, and the mutants with improved affinity to FcγRs reduce phagocytosis at lower concentrations than wildtype variants. Consistent with thie theory, competition with serum IgG has been cited as a major factor in driving the high concentrations of antibody required to elicit effector functions in vivo(Iida et al., 2006). This phenomenon highlights the complexity of Fc domain-driven effector functions as there are numerous binding interactions taking place: binding of the variable domain arms to the antigen, and binding of the Fc domain to each FcγR—whether when antibody is free in solution, or multimerized on opsonized beads resulting in an avidity advantage.

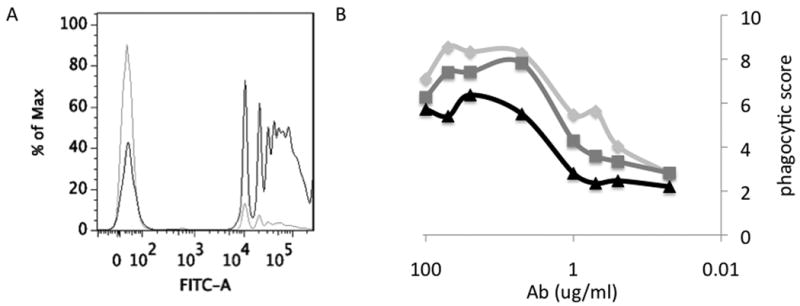

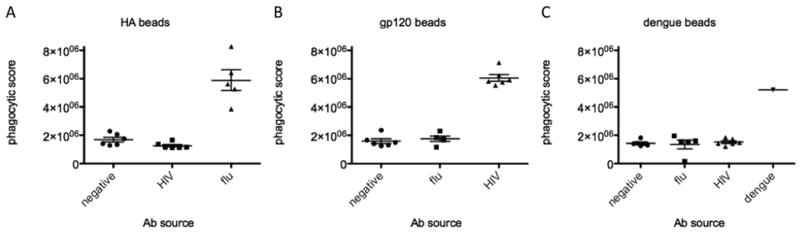

3.6 Scoring phagocytosis from clinical samples

In order to demonstrate the usefulness of this assay in scoring the phagocytic profile of antibody samples from patients, we tested antibody samples from patients against beads coated with antigens from dengue, flu, and HIV. Figure 6A presents the flow cytometry histogram traces of a flu patient's antibodies against hemagglutinin (black) and dengue-coated beads (gray), indicating low levels of uptake against dengue, and high phagocytic activity against hemagglutinin-coated beads, demonstrating the clear antigen-specific nature of this assay. For each patient, an antibody dose-response curve was generated. Several representative phagocytic activity curves of flu patients are presented in Figure 6B, demonstrating a range of phagocytic activities among these three patients, potentially reflecting differences in antibody-glycosylation. The antigen specific nature of this activity was further confirmed using beads coated with various pathogen envelopes. Thus antibody samples from negative, HIV positive, and flu positive patients were each tested for phagocytic activity against hemagglutinin (Figure 7A), gp120 (7B), and dengue-coated (7C) beads, demonstrating specificity for each disease antigen. As a positive control for dengue-coated beads, a monoclonal anti-dengue antibody was used. Thus overall these data demonstrate that the phagocytic profile of clinical antibody samples can be reliably determined by this methodology. Furthermore, by utilizing variant envelope proteins to coat beads, there exists the possibility to study cross-clade or cross-virus differences in antibody-dependent phagocytosis.

Figure 6. Antigen specificity of antibody-dependent phagocytosis.

A. FACS histogram showing representative data for flu antibodies incubated with dengue beads (gray) or hemagglutinin beads (black). B. Antibody dose-response curve from a single replicate for 3 flu patients are depicted.

Figure 7. Antibody-dependent phagocytosis of patient samples.

A. The dot plot represents maximum phagocytic scores of antibodies from negative, HIV positive, or flu positive individuals against hemagglutinin-coated beads. B. Diagrams show phagocytic scores of antibodies from negative, HIV positive, or flu positive individuals against gp120-coated beads. C. Finally, the figure demonstrates phagocytic scores of antibodies from negative, HIV positive, flu positive individuals, or a mouse IgG2A anti-dengue monoclonal against dengue antigen-coated beads.

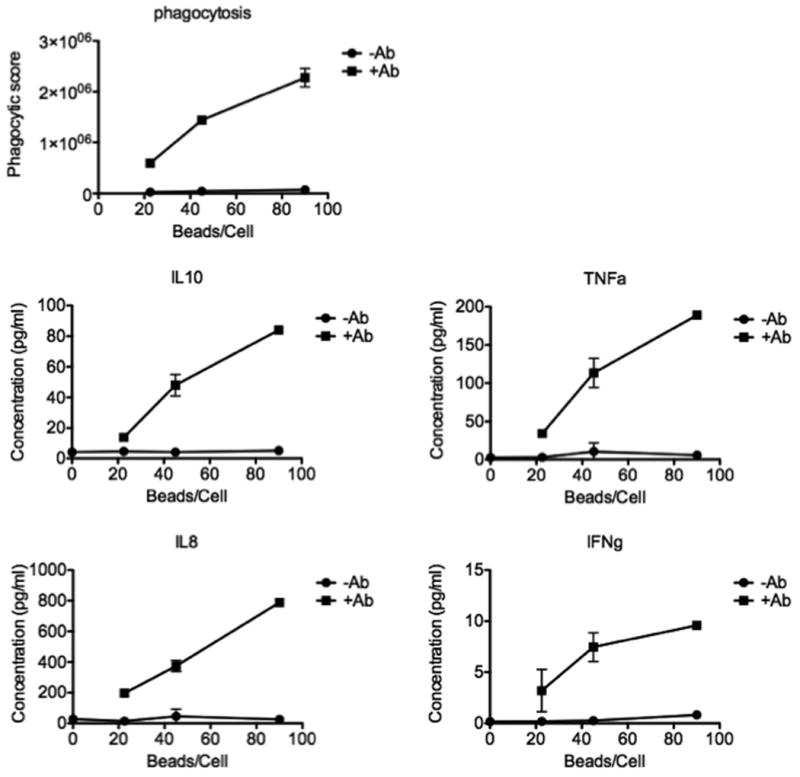

3.7 Analysis of cytokine secretion

Phagocytosis has been shown to enhance several additional effector functions in phagocytic cells, including cytokine/chemokine secretion that either enhances or dampens infection associated inflammation(Friedland et al., 1993b). Thus we were intrigued to next define whether this high-throughput flow based antibody-mediated phagocytosis assay could also provide an opportunity to characterize changes in the activity of phagocytic cells following the induction of phagocytosis. Thus cytokine release was determined utilizing a luminex assay. Numerous cytokines reported to be produced by monocytes, including both immunostimulatory and immunosuppressive cytokines, were monitored concurrently. As negative controls, untreated cells, and cells treated with uncoated beads were tested for their secretion profiles, and beads were tested at a range of concentrations. Secretion of several cytokines in the panel was increased in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 8). Because different receptor usage profiles may trigger signaling via different pathways and therefore lead to differing cytokine release profiles, profiling cell supernatants in this way may provide an additional point of comparison between patient samples. Thus, while THP-1 cells have been used frequently in studies of cytokine release and the oxidative burst which occurs following phagocytosis(Gross et al., 1998; Kurosaka et al., 1998; Shaw et al., 2000; Miyazawa et al., 2007), the specific cytokine release profiles for this cell line may not correspond to signals occurring naturally during phagocytosis mediated by heterogeneous populations of primary cells, however these data may provide more profound understanding of qualitatively unique antibody effector functions in this high-throughput cell line based screening method that can be later teased out on primary cells.

Figure 8. Cytokine release.

Line graphs represent multiplexed analysis of phagocytic scores and corresponding cytokine secretion from cells left untreated, incubated with uncoated beads (circles) or antibody-coated beads (squares) showing strong antibody and dose-dependent phagocytosis-induced release of several cytokines

3.8 Defining the durability of antibody-mediated phagocytosis

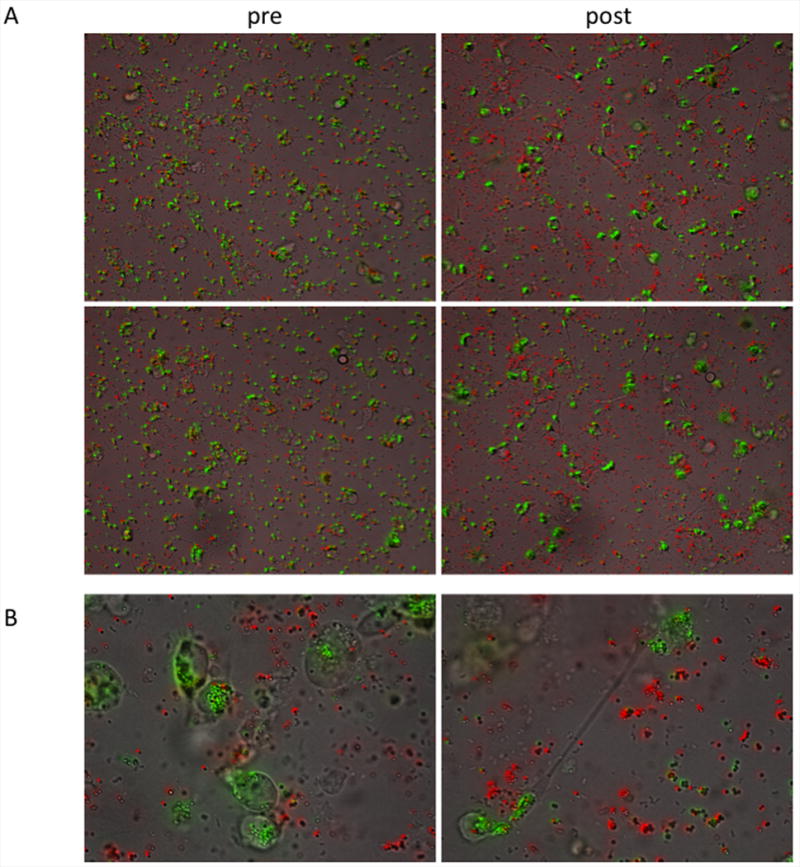

Lastly, given that THP-1 cells released a number of proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines after co-culture with antibody-coated beads, we were interested to determine whether under such inflammatory conditions activated THP-1 cells would begin to take up beads in an antibody-independent manner by using time-lapse microscopy. For these experiments, both antibody-coated (green) and bare (red) beads were incubated with cells and 14-hour time-lapse microscopy images were collected. Figure 9A presents the first and last frames of movies included as Movies 1 and 2 in the online version, and demonstrates the scattered distribution of both antibody-coated and bare beads at initial timepoints, but punctate, cell-associated distribution of antibody-coated beads at the conclusion of the experiment. Movie 3 presents a magnification of the phagocytic behavior observed. Despite being stimulated by the presence of opsonized particles, the monocytes retain a striking preference for phagocytosing antibody-coated beads, and are frequently observed to contact both bead types but only take up the opsonized beads. Figure 9B presents still images at 63× magnification, and again clearly demonstrates the lack of uptake in the absence of antibody. Thus these data strongly suggest that even under inflammatory conditions, the THP-1 cells used in this assay retain the capacity to selectively phagocytose antibody-opsonized material.

Figure 9. Time-lapse microscopy of phagocytosis.

Antibody-coated (green) and bare (red) beads were incubated with THP-1 cells on coverslips for time lapse microscopy, demonstrating antibody-specific uptake. A. 20× magnification still images representing the first (left) and final (right) frames from two 14 hour experiments. B. Representative 63× magnification images at 14 hours.

3.9 Assay Performance Criteria

The performance metrics associated with the phagocytosis assay presented here include linearity under conditions of limiting antibody (Figure 4C); precise antigen specificity, as demonstrated by the analysis of patient samples with mismatched antigen beads, as well as testing of mismatched monoclonals (Figure 7); precise Fc domain specificity, as demonstrated by experiments with deglycosylated and point-mutated Fc domains; sensitivity down to 5 ng/ml of monoclonal antibody (below the Fv Kd), and 50 ng/ml for patient antibody samples, although these values are dependent on the Fv domain affinity as well as titer; and high reproducibility, with coefficients of variation of less than 0.10 on assays conducted on different days, and 0.06 within the same experiment. Additionally, a significant correlation between phagocytosis in assays utilizing THP-1 cells and primary monocytes for a set of patient samples has also been observed, suggesting that the results generated from this cell line provide relevant information related to results anticipated from primary cells (data not shown). However we anticipate that the primary utility of the assay will be in differentiating the ability of clinical antibody samples to induce phagocytosis rather than in reproducing the complex phagocytic processes occurring in heterogeneous populations of primary cells, which can later be parsed out following identification of unique antibody populations that mediate robust activity in this high-throughput assay.

4. Conclusion

Overall, because innate immune recruiting effector functions have been underappreciated in the protective capacity of even neutralizing antibodies, and phagocytosis might be important in the initial control and clearance of pathogens, an assay capable of measuring this effector function represents an important means of characterizing the immune response to infection or vaccination. Challenges related to the study of effector functions include the large number of FcγRs with variable affinities, expression levels, and signaling capacities. Beyond this, antibody-dependent complement deposition, coupled with defects in phagocytes due to infection, and the prosaic concentration effects of antibodies further confound the study of phagocytosis. Despite these challenges, we have described a robust and high-throughput flow cytometric assay to define the phagocytic activity of antibodies from clinical samples. Because this assay employs a widely utilized monocytic cell line that expresses numerous FcγRs, including both inhibitory and activating, complex phenotypes can be studied. Furthermore, the standardization permitted by utilizing a cell line is important for large scale monitoring of antibody samples from infection and vaccination. We have demonstrated that the assay described here is able to resolve the involvement of individual FcγRs, monitor cytokine release, and detect differences in phagocytosis due to the glycan structure of antigen-specific antibodies, making it a highly useful system for parsing differences in this potentially vital antibody-dependent effector function in both infection and vaccine-mediated protection.

Supplementary Material

Time-lapse microscopy of THP-1 cell phagocytosis of opsonized (green) and uncoated (red) beads, field of view 1.

Time-lapse microscopy of THP-1 cell phagocytosis of opsonized (green) and uncoated (red) beads, field of view 2.

Detailed view of THP-1 cell phagocytosis of opsonized beads.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allhorn M, Olin AI, Nimmerjahn F, Collin M. Human IgG/Fc gamma R interactions are modulated by streptococcal IgG glycan hydrolysis. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1413. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony RM, Ravetch JV. A novel role for the IgG Fc glycan: the anti-inflammatory activity of sialylated IgG Fcs. J Clin Immunol. 2010;30 1:S9–14. doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9405-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslam A, Quinn P, McIntosh RS, Shi J, Ghumra A, McKerrow JH, Bunting KA, Dunne DW, Doenhoff MJ, Morrison SL, Zhang K, Pleass RJ. Proteases from Schistosoma mansoni cercariae cleave IgE at solvent exposed interdomain regions. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:567–74. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berasain P, Carmona C, Frangione B, Dalton JP, Goni F. Fasciola hepatica: parasite-secreted proteinases degrade all human IgG subclasses: determination of the specific cleavage sites and identification of the immunoglobulin fragments produced. Exp Parasitol. 2000;94:99–110. doi: 10.1006/expr.1999.4479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard J, Reveil B, Najman I, Liautaud-Roger F, Fouchard M, Picard O, Cattan A, Mabondzo A, Laverne S, Gallo RC, et al. Discriminating between protective and enhancing HIV antibodies. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1990;6:243–9. doi: 10.1089/aid.1990.6.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beum PV, Mack DA, Pawluczkowycz AW, Lindorfer MA, Taylor RP. Binding of rituximab, trastuzumab, cetuximab, or mAb T101 to cancer cells promotes trogocytosis mediated by THP-1 cells and monocytes. J Immunol. 2008;181:8120–32. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.8120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd PN, Lines AC, Patel AK. The effect of the removal of sialic acid, galactose and total carbohydrate on the functional activity of Campath-1H. Mol Immunol. 1995;32:1311–8. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(95)00118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clynes RA, Towers TL, Presta LG, Ravetch JV. Inhibitory Fc receptors modulate in vivo cytoxicity against tumor targets. Nat Med. 2000;6:443–6. doi: 10.1038/74704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collin M, Svensson MD, Sjoholm AG, Jensenius JC, Sjobring U, Olsen A. EndoS and SpeB from Streptococcus pyogenes inhibit immunoglobulin-mediated opsonophagocytosis. Infect Immun. 2002;70:6646–51. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.12.6646-6651.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dall'Ozzo S, Tartas S, Paintaud G, Cartron G, Colombat P, Bardos P, Watier H, Thibault G. Rituximab-dependent cytotoxicity by natural killer cells: influence of FCGR3A polymorphism on the concentration-effect relationship. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4664–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darrah PA, Patel DT, De Luca PM, Lindsay RW, Davey DF, Flynn BJ, Hoff ST, Andersen P, Reed SG, Morris SL, Roederer M, Seder RA. Multifunctional TH1 cells define a correlate of vaccine-mediated protection against Leishmania major. Nat Med. 2007;13:843–50. doi: 10.1038/nm1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleit HB, Kobasiuk CD. The human monocyte-like cell line THP-1 expresses Fc gamma RI and Fc gamma RII. J Leukoc Biol. 1991;49:556–65. doi: 10.1002/jlb.49.6.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flesch BK, Achtert G, Neppert J. Inhibition of monocyte and polymorphonuclear granulocyte immune phagocytosis by monoclonal antibodies specific for Fc gamma RI, II and III. Ann Hematol. 1997;74:15–22. doi: 10.1007/s002770050249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedland JS, Shattock RJ, Griffin GE. Phagocytosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis or particulate stimuli by human monocytic cells induces equivalent monocyte chemotactic protein-1 gene expression. Cytokine. 1993a;5:150–6. doi: 10.1016/1043-4666(93)90054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedland JS, Shattock RJ, Johnson JD, Remick DG, Holliman RE, Griffin GE. Differential cytokine gene expression and secretion after phagocytosis by a human monocytic cell line of Toxoplasma gondii compared with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1993b;91:282–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb05896.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fust G, Toth FD, Kiss J, Ujhelyi E, Nagy I, Banhegyi D. Neutralizing and enhancing antibodies measured in complement-restored serum samples from HIV-1-infected individuals correlate with immunosuppression and disease. AIDS. 1994;8:603–9. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199405000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross A, Dugas N, Spiesser S, Vouldoukis I, Damais C, Kolb JP, Dugas B, Dornand J. Nitric oxide production in human macrophagic cells phagocytizing opsonized zymosan: direct characterization by measurement of the luminol dependent chemiluminescence. Free Radic Res. 1998;28:179–91. doi: 10.3109/10715769809065803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halstead SB, O'Rourke EJ. Dengue viruses and mononuclear phagocytes. I. Infection enhancement by non-neutralizing antibody. J Exp Med. 1977;146:201–17. doi: 10.1084/jem.146.1.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessell AJ, Hangartner L, Hunter M, Havenith CE, Beurskens FJ, Bakker JM, Lanigan CM, Landucci G, Forthal DN, Parren PW, Marx PA, Burton DR. Fc receptor but not complement binding is important in antibody protection against HIV. Nature. 2007;449:101–4. doi: 10.1038/nature06106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida S, Misaka H, Inoue M, Shibata M, Nakano R, Yamane-Ohnuki N, Wakitani M, Yano K, Shitara K, Satoh M. Nonfucosylated therapeutic IgG1 antibody can evade the inhibitory effect of serum immunoglobulin G on antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity through its high binding to FcgammaRIIIa. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2879–87. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson P, Glennie M. The mechanisms of action of rituximab in the elimination of tumor cells. Semin Oncol. 2003;30:3–8. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2003.50025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko Y, Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Anti-inflammatory activity of immunoglobulin G resulting from Fc sialylation. Science. 2006;313:670–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1129594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapetanovic R, Nahori MA, Balloy V, Fitting C, Philpott DJ, Cavaillon JM, Adib-Conquy M. Contribution of phagocytosis and intracellular sensing for cytokine production by Staphylococcus aureus-activated macrophages. Infect Immun. 2007;75:830–7. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01199-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski PA, Black KP, Shen L, Jackson S. High prevalence of serum IgA HIV-1 infection-enhancing antibodies in HIV-infected persons. Masking by IgG. J Immunol. 1995;154:6163–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosaka K, Watanabe N, Kobayashi Y. Production of proinflammatory cytokines by phorbol myristate acetate-treated THP-1 cells and monocyte-derived macrophages after phagocytosis of apoptotic CTLL-2 cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:6245–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laszlo A, Petri I, Ilyes M. Antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC)-reaction and an in vitro steroid sensitivity test of peripheral lymphocytes in children with malignant haematological and autoimmune diseases. Acta Paediatr Hung. 1986;27:23–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Nauseef WM, Moeenrezakhanlou A, Sly LM, Noubir S, Leidal KG, Schlomann JM, Krystal G, Reiner NE. Monocyte p110alpha phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase regulates phagocytosis, the phagocyte oxidase, and cytokine production. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:1548–61. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0906564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littaua R, Kurane I, Ennis FA. Human IgG Fc receptor II mediates antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue virus infection. J Immunol. 1990;144:3183–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund J, Takahashi N, Pound JD, Goodall M, Jefferis R. Multiple interactions of IgG with its core oligosaccharide can modulate recognition by complement and human Fc gamma receptor I and influence the synthesis of its oligosaccharide chains. J Immunol. 1996;157:4963–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchette NJ, Halstead SB, O'Rourke T, Scott RM, Bancroft WH, Vanopruks V. Effect of immune status on dengue 2 virus replication in cultured leukocytes from infants and children. Infect Immun. 1979;24:47–50. doi: 10.1128/iai.24.1.47-50.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazawa M, Ito Y, Yoshida Y, Sakaguchi H, Suzuki H. Phenotypic alterations and cytokine production in THP-1 cells in response to allergens. Toxicol In Vitro. 2007;21:428–37. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimmerjahn F, Anthony RM, Ravetch JV. Agalactosylated IgG antibodies depend on cellular Fc receptors for in vivo activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8433–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702936104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raju TS. Terminal sugars of Fc glycans influence antibody effector functions of IgGs. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:471–8. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JO, Karki S, Lazar GA, Chen H, Dang W, Desjarlais JR. Optimization of antibody binding to FcgammaRIIa enhances macrophage phagocytosis of tumor cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:2517–27. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scallon BJ, Tam SH, McCarthy SG, Cai AN, Raju TS. Higher levels of sialylated Fc glycans in immunoglobulin G molecules can adversely impact functionality. Mol Immunol. 2007;44:1524–34. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiff DE, Kline L, Soldau K, Lee JD, Pugin J, Tobias PS, Ulevitch RJ. Phagocytosis of gram-negative bacteria by a unique CD14-dependent mechanism. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;62:786–94. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.6.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt RE, Gessner JE. Fc receptors and their interaction with complement in autoimmunity. Immunol Lett. 2005;100:56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2005.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakirova RG, German GP, Chernokhvostova EV. IgA protease activity of microbes in the genus Bordetella. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol. 1985:10–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw TC, Thomas LH, Friedland JS. Regulation of IL-10 secretion after phagocytosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by human monocytic cells. Cytokine. 2000;12:483–6. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1999.0586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields RL, Lai J, Keck R, O'Connell LY, Hong K, Meng YG, Weikert SH, Presta LG. Lack of fucose on human IgG1 N-linked oligosaccharide improves binding to human Fcgamma RIII and antibody-dependent cellular toxicity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:26733–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202069200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields RL, Namenuk AK, Hong K, Meng YG, Rae J, Briggs J, Xie D, Lai J, Stadlen A, Li B, Fox JA, Presta LG. High resolution mapping of the binding site on human IgG1 for Fc gamma RI, Fc gamma RII, Fc gamma RIII, and FcRn and design of IgG1 variants with improved binding to the Fc gamma R. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:6591–604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009483200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore SL, Nahmias AJ, Starr SE, Wood PA, McFarlin DE. Detection of cell-dependent cytotoxic antibody to cells infected with herpes simplex virus. Nature. 1974;251:350–2. doi: 10.1038/251350a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taborda CP, Rivera J, Zaragoza O, Casadevall A. More is not necessarily better: prozone-like effects in passive immunization with IgG. J Immunol. 2003;170:3621–30. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura M, Webster RG, Ennis FA. Antibodies to HA and NA augment uptake of influenza A viruses into cells via Fc receptor entry. Virology. 1991;182:211–9. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90664-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tebo AE, Kremsner PG, Luty AJ. Fcgamma receptor-mediated phagocytosis of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes in vitro. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;130:300–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01972.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya S, Kobayashi Y, Goto Y, Okumura H, Nakae S, Konno T, Tada K. Induction of maturation in cultured human monocytic leukemia cells by a phorbol diester. Cancer Res. 1982;42:1530–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya S, Yamabe M, Yamaguchi Y, Kobayashi Y, Konno T, Tada K. Establishment and characterization of a human acute monocytic leukemia cell line (THP-1) Int J Cancer. 1980;26:171–6. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910260208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidarsson G, Overbeeke N, Stemerding AM, van den Dobbelsteen G, van Ulsen P, van der Ley P, Kilian M, van de Winkel JG. Working mechanism of immunoglobulin A1 (IgA1) protease: cleavage of IgA1 antibody to Neisseria meningitidis PorA requires de novo synthesis of IgA1 Protease. Infect Immun. 2005;73:6721–6. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6721-6726.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi Y, Nishimura M, Nagano M, Yagi H, Sasakawa H, Uchida K, Shitara K, Kato K. Glycoform-dependent conformational alteration of the Fc region of human immunoglobulin G1 as revealed by NMR spectroscopy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1760:693–700. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Time-lapse microscopy of THP-1 cell phagocytosis of opsonized (green) and uncoated (red) beads, field of view 1.

Time-lapse microscopy of THP-1 cell phagocytosis of opsonized (green) and uncoated (red) beads, field of view 2.

Detailed view of THP-1 cell phagocytosis of opsonized beads.