Abstract

Protein tyrosine nitration has been observed in a variety of human diseases associated with oxidative stress, such as inflammatory, neurodegenerative and cardiovascular conditions. However, the pathways leading to nitration of tyrosine residues are still unclear. Recent studies have shown that peroxynitrite (PN), produced by the reaction of superoxide and nitric oxide, can lead to protein nitration and inactivation. Tyrosine nitration may also be mediated by nitrogen dioxide produced by the oxidation of nitrite by peroxidases. Manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD), which plays a critical role in cellular defense against oxidative stress by decomposing superoxide within mitochondria, is nitrated and inactivated under pathological conditions. In this study, MnSOD is shown to catalyze PN-mediated self-nitration. Direct, spectroscopic observation of the kinetics of PN decay and nitrotyrosine formation (kcat = 9.3 × 102 M-1s-1) indicates that the mechanism involves redox cycling between Mn2+ and Mn3+, similar to that observed with superoxide. Distinctive patterns of tyrosine nitration within MnSOD by various reagents were revealed and quantified by MS/MS analysis of MnSOD trypsin digest peptides. These analyses showed that three of the seven tyrosine residues of MnSOD (Tyr34, Tyr9, and Tyr11) were most susceptible to nitration and that the relative amounts of nitration of these residues varied widely depending upon the nature of the nitrating agent. Notably, nitration mediated by PN, both in the presence and absence of CO2, resulted in nitration of the active site tyrosine, Tyr34, while nitration by freely diffusing nitrogen dioxide led to surface nitration at Tyr9 and Tyr11. Flux analysis of the nitration of Tyr34 by PN-CO2 showed that the nitration rate coincided with the kinetics of the reaction of PN with CO2. These kinetics and the 20-fold increase in the efficiency of tyrosine nitration in the presence of CO2 suggest a specific role for the carbonate radical anion (•CO3-) in MnSOD nitration by PN. We also observed that the nitration of Tyr34 caused inactivation of the enzyme, while nitration of Tyr9 and Tyr11 did not interfere with the superoxide dismutase activity. The loss of MnSOD activity upon Tyr34 nitration implies that the responsible reagent in vivo is peroxynitrite, acting either directly or through the action of •CO3-.

INTRODUCTION

Protein tyrosine nitration has been observed in connection with numerous human diseases including neurodegenerative conditions, cardiovascular disorders, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease.1-8 Recent evidence suggests that protein nitration is an early event disease development, emphasizing its role in the etiology of these disorders.7,9-11 Although the underlying mechanism of protein nitration in vivo is still unclear, two reactive nitrogen compounds, the peroxynitrite anion (ONOO-) and nitrogen dioxide (•NO2), are thought to be involved. Peroxynitrite (PN) is formed by the rapid reaction of •NO with •O2-; with •NO being produced by cells as an important cellular messenger and •O2- deriving largely from mitochondrial respiration.1,3,5,12-20 Nitrogen dioxide could be formed from PN decomposition or via the one-electron oxidation of nitrite ion, itself a cellular metabolite of •NO.21-24 Due to the transient nature of both PN and •NO2, it has not been feasible to observe them directly within cells. Accordingly, unambiguous evidence to identify which species and pathways are responsible for nitration in vivo is still lacking.

Manganese-superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) is one of the critical enzymes that is nitrated and inactivated in vivo under pathological conditions.25-32 MnSOD is located in the mitochondrial matrix of eukaryotes and in a variety of prokaryotes, where it catalyzes the disproportionation of •O2- to O2 and H2O2.33-35 Significantly, MnSOD appears to be hypersensitive toward nitration, accounting for as much as 20% of total protein nitration under conditions of oxidative stress.27 MnSOD inhibits PN formation in mitochondria by scavenging its precursor, •O2-. Over-expression of MnSOD can suppress cell damage due to nitrosative stress.32,36-37 However, MnSOD can be inactivated due to nitration of critical tyrosine residues. Diabolically, this inactivation can lead to amplification of PN formation and increase in cellular damage.38-40 MnSOD is thought to play a role in the cell cycle via its control over the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Suppression of MnSOD by pro-apoptotic genes p53 and c-Myc is known to induce apoptosis due to increase in ROS.41 Nitration of MnSOD also results in loss of activity, showing that it may also play a role in the induction of apoptosis.

As noted above, MnSOD nitration in vivo could be due to direct reaction with peroxynitrite or via freely diffusing •NO2. Knowing which of these species is the causative agent for protein nitration could have important ramifications in our understanding to the origins of cell damage and the underlying disease. Here we report clear evidence that the positional selectivities of tyrosine nitration for the peroxynitrite and •NO2 pathways are significantly different. Previous studies have shown that the positional selectivity of protein tyrosine nitration by peroxynitrite can be different than •NO2.42-43 We have employed the differences in selectivity between these agents for MnSOD to identify the pathways leading to nitration. Direct reaction with peroxynitrite has been found to result in the nitration of Tyr34, close to the active site manganese, both with and without added CO2, while reaction with freely diffusing •NO2 results in nitration of the most solvent-accessible tyrosine residues (Tyr9 and Tyr11). In addition, nitration of Tyr34 causes inactivation of the enzyme, while nitration of surface residues does not. We also investigate the mechanism and role of the active site manganese in the reaction of MnSOD and peroxynitrite. In this study, E. coli MnSOD was used as a model to understand the interactions of human MnSOD with peroxynitrite since the human and bacterial forms are highly homologous and their active site structures are superimposable.44-46

RESULTS

First, we report the direct observation of tyrosine nitration by detecting its characteristic chromophore. Then, the position of nitration and the effect of catalysis on the selectivity of nitration were determined by bottom-up proteomics. Finally, the mechanism of the reaction between peroxynitrite and MnSOD was probed by spectroscopic methods.

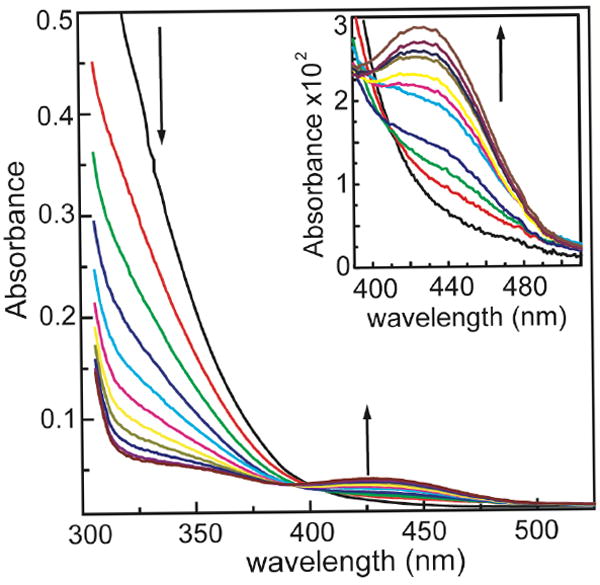

The nitration of MnSOD by peroxynitrite, as monitored by stopped-flow spectroscopy

The reaction of 15 μM MnSOD and 0.4 mM PN resulted in a decrease in PN absorbance measured at 320 nm and a concurrent increase in absorbance at 430 nm (Figure 1). The absorbance at 430 nm was attributed to nitrotyrosine formation due to the characteristic shift observed in its peak wavelength from 430 nm to 357 nm with decreasing pH.47 The yield of nitration under these conditions was 15 % nitration per subunit of MnSOD, based on the known OD of nitrotyrosine; this corresponds to nitration of one tyrosine out of the seven per MnSOD monomer.

Figure 1.

Reaction of 15 μM MnSOD with 0.4 mM PN at pH 7.4 and 25°C. During the course of the reaction, as the PN decays, a new peak at 430 nm appears that is assigned to nitrotyrosine. Inset: Magnification of increase in nitrotyrosine formation observed at 430 nm.

Kinetics of the formation of nitrotyrosine as a result of the reaction between MnSOD and PN (0.5 mM) was followed by the change in absorbance at 430 nm with increasing concentrations of MnSOD; the kinetics of nitrotyrosine formation by PN did not follow simple first order kinetics since they appear linear during the first 10 s (Figure S1).

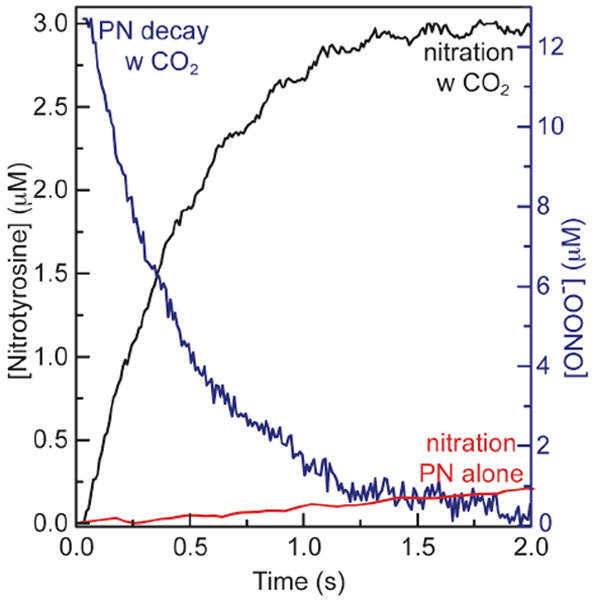

Carbon dioxide increased the efficiency of MnSOD Tyr34 nitration by peroxynitrite

The rates of peroxynitrite decay and formation of MnSOD-nitrotyrosine as well as the yield of nitrated tyrosines were greatly increased in the presence of bicarbonate/carbon dioxide. Formation of nitrotyrosine and decay of PN were monitored during the nitration of 10 μM MnSOD by 13 μM PN in the presence of 0.1 mM carbon dioxide, via the changes in absorbance at 430 nm and 320 nm respectively (Figure 2). The yield of nitration with a slight stoichiometric excess of PN in the presence of CO2 was approximately an order of magnitude larger than what was observed with PN alone under similar conditions (23 % nitration in the presence of CO2, 3.7 % nitration in the absence of CO2 by PN (13 μM) with respect to PN).

Figure 2.

Decay of PN (blue trace) and formation of nitrotyrosine (black trace) in the reaction of 10 μM MnSOD with 13 μM of PN in the presence of 0.1 mM CO2 in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 and 25°C. Red trace shows the time course of the nitrotyrosine formation without CO2. In addition, formation of nitrotyrosine in the reaction of 10 μM MnSOD with 18 μM PN, in the absence of CO2, in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 and 25°C is shown (during the first 2 s).

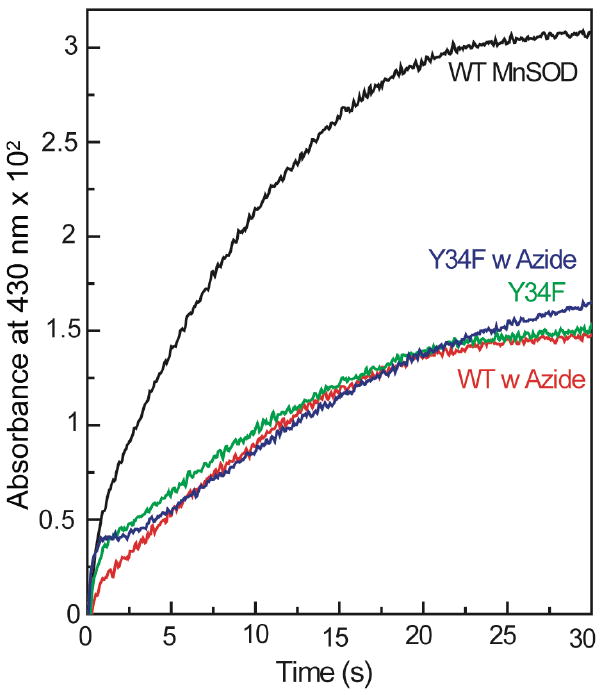

Azide inhibited MnSOD nitration by peroxynitrite

As explained above the nitration of MnSOD by peroxynitrite can be monitored in the stopped flow spectrometer by following the absorbance at 430 nm. The effects of azide on MnSOD nitration by PN was tested, because azide is known to bind to manganese at the active site and to inhibit the activity of MnSOD48-49. In the presence of azide (0.8 mM) there was a significant decrease in nitration of MnSOD (10 μM) by PN (0.5 mM), monitored by increase in absorbance at 430 nm. On the other hand, nitration of Y34F variant of MnSOD (10 μM) by PN (0.5 mM) was unaffected by the presence of azide (0.8 mM) (Figure 3). In addition, the kinetics of nitration of the Y34F MnSOD - in the absence or presence of azide - and native MnSOD in the presence of azide were indistinguishable. It is important to note that under these conditions, the percent of active site manganese in MnSOD bound to azide was only around 10%, calculated using the KD of azide from literature.48

Figure 3.

Formation of nitrotyrosine in the reaction of wild type (WT) and Y34F MnSOD with PN in the absence and presence of azide followed by measuring the absorbance at 430 nm. The reaction of 0.5 mM PN with 10 μM MnSOD and 10 μM Y34F MnSOD in the absence and presence of 0.8 mM azide was carried out at pH 7.4 and 25°C in 0.25 M potassium phosphate buffer and 0.1 mM DTPA.

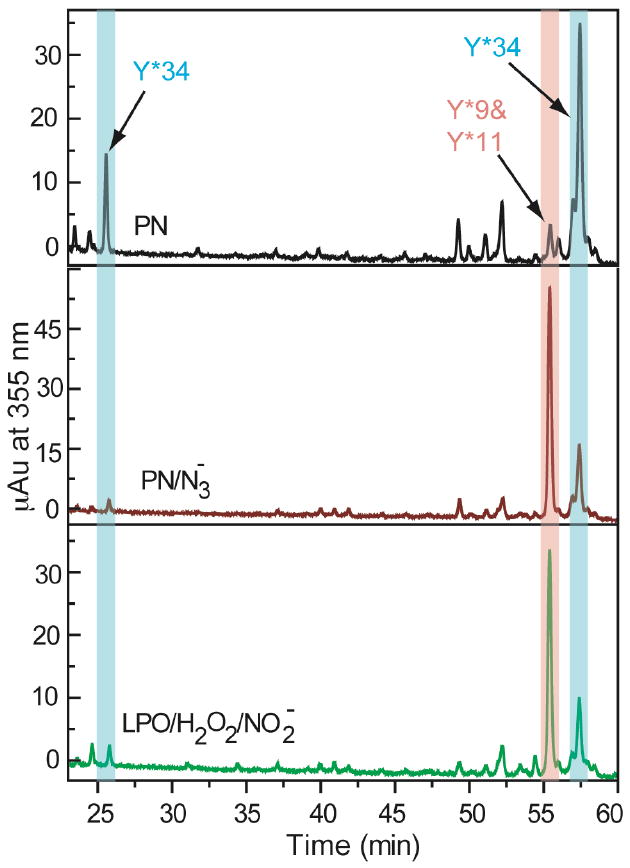

Positional selectivity of MnSOD nitration by various nitrating agents

The pattern of MnSOD nitration was determined under a variety of nitrating conditions. In preparation for this analysis, 10 μM MnSOD was reacted with 0.3 mM (or 35 μM in the presence of CO2) PN in the presence and absence of 1.5 mM azide and/or 0.175 mM CO2 (in equilibrium with 2 mM HCO3-) using the stopped-flow apparatus. In addition 10 μM MnSOD was nitrated by 0.05 μM LPO in the presence of 2 mM NaNO2 and 2 mM H2O2 or by 1 mM TNM. Nitrated MnSOD was digested by trypsin, and analysis of the tryptic digests by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS revealed the relative amounts of nitration of each residue (Figure S3). Each nitrated tyrosine or tryptophan was identified by assigning the corresponding MS/MS spectrum to the expected peptide fragment (Figure S4-7). The relative amount of nitrotyrosine or nitrotryptophan that corresponded to each fragment was quantified by observation of the UV absorbance at 355 nm, as seen in Figure 4. This information allowed us to determine the relative amount of nitration of specific residue with respect to total nitration (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Liquid chromatogram of peptides containing nitrated tyrosine and tryptophan residues from nitrated MnSOD digested by trypsin. Top to bottom: MnSOD nitrated by PN in the absence and presence of azide and MnSOD nitrated by LPO, H2O2 and NO2-, respectively. MnSOD nitrated by PN in the presence of CO2 looks very similar to nitration with PN alone (Figure S2, Supporting Information). There are two peptides containing nitrated Tyr34 due to over-digestion of the main peptide after nitrated-Tyr34 (Figure S6).

Table 1.

The relative amounts of nitration for each tyrosine of MnSOD nitrated under different conditions. MnSOD was nitrated by PN alone or in the presence of azide and/or CO2, or by LPO in the presence of NO2- and H2O2, or by TNM. Total protein nitration was estimated by ESI-MS of intact protein.

| Tyrosine or Tryptophan residue | Relative amount of nitration (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PN | PN + N3- | PN + CO2 | PN + CO2 + N3- | LPO/H2O2/NO2- | TNM | |

| Y34 | 76 | 30 | 82 | 34 | 27 | 48 |

| Y2-Y9-Y11a | 6 | 61 | 2 | 59 | 59 | 26 |

| W189 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| W194 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 11 |

| Other | 12 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 11 |

| Total MnSOD nitration (%)b | 20 | 17 | 16 | 15 | 12 | 8 |

Nitration of tyrosine residues at position 34, 9 and 11 was responsible for 74-93% of identified MnSOD nitration. The residues Tyr9 and Tyr11 were on the same tryptic peptide, therefore it was not possible to distinguish the nitration of Tyr9 and Tyr11, and so we considered them together.

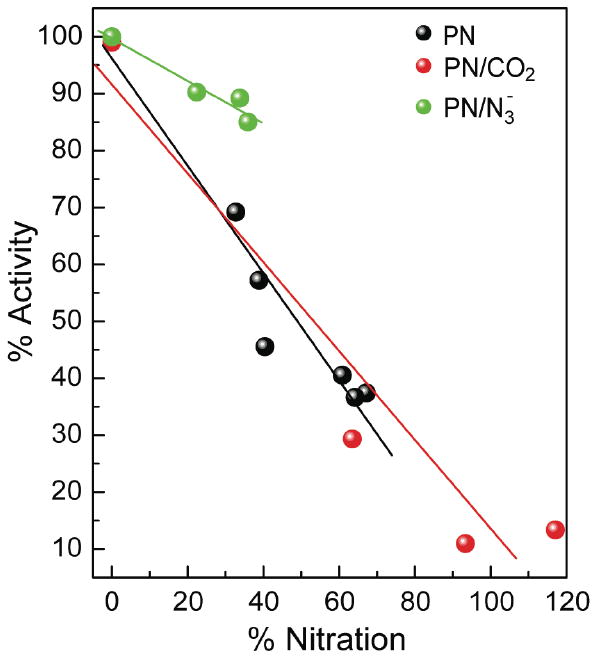

Only nitration of MnSOD at the active side interfered with the activity of MnSOD

In accordance with our observation that different tyrosine residues of MnSOD were nitrated by different agents of nitration, we investigated whether the pattern of nitration had an effect on enzyme activity. The loss of activity of MnSOD when it was nitrated by PN in the absence and presence of CO2 or azide was compared. MnSOD was reacted with increasing equivalents of PN in the absence or presence of azide or CO2; for each sample we determined the amount of nitration by monitoring the absorbance at 430 nm, and the percent activity with respect to native MnSOD. There was a significant decrease in activity of MnSOD due to nitration when MnSOD was nitrated by PN in absence or presence of CO2. However, when MnSOD was nitrated by PN in the presence of azide significantly more activity was retained (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

A. The changes in activity of MnSOD after nitration by PN in the absence and presence of carbon dioxide are shown. MnSOD (10 μM) was nitrated with PN (0.3 - 1 mM) in 0.25 M phosphate buffer at pH 7.4, 25°C. B. The changes in activity of MnSOD after nitration by PN in the absence and presence of azide. MnSOD (8 μM) was nitrated with PN (0.2 - 0.8 mM) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer at pH 7.4, 25°C.

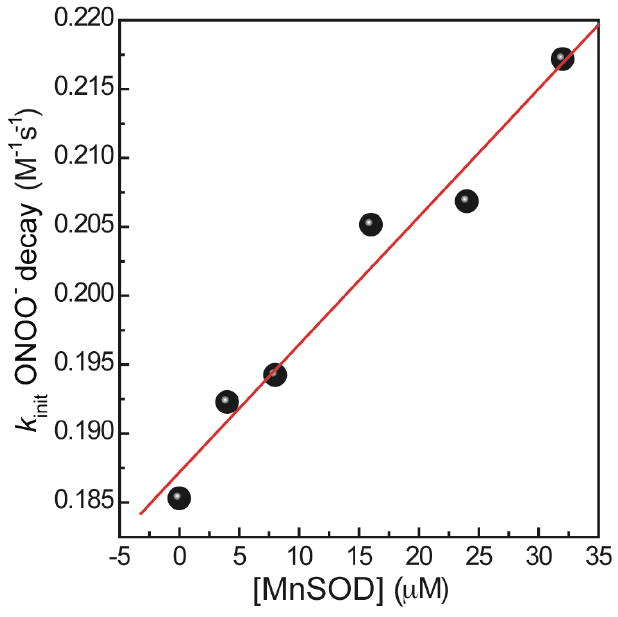

Determination of the catalytic rate constant for the reaction of MnSOD and peroxynitrite

The second order rate constant for the reaction between MnSOD and peroxynitrite was obtained by monitoring the decomposition kinetics of peroxynitrite in the presence of MnSOD by stopped-flow spectrometry. The presence of MnSOD (0-40 μM) resulted in acceleration of the PN decay. A second order rate constant kcat = 9.3 ± 0.9 × 102 M-1s-1 (at pH 7.4 and 25 °C) was determined by the initial rate approach, since pseudo first order conditions could not be realized (Figure 6). In this approach, the rate of PN decay in the presence of MnSOD can be described by eq 1, where k0 denotes the rate constant for spontaneous PN decay, and kcat represents the rate constant for the reaction between PN and MnSOD. The value of kcat was obtained from the slope of PN decay rate versus initial MnSOD concentration (Figure 6). We note that the value of kcat obtained here is not in agreement with the previously reported rate constant 1.4 ± 0.2 × 105 M-1s-1 at pH 7.4 and 37 °C.50 The first order rate constant of PN spontaneous decay was measured to be 0.19 (± 0.02) s-1 at pH 7.4 and 25°C, which is in good agreement with values in literature

| (1) |

Figure 6.

Determination of catalytic rate constant for the reaction of PN with MnSOD at pH 7.4 and 25°C. MnSOD (4-32 μM) reacts with PN (0.15 mM) in 0.25 M potassium phosphate buffer at 25°C and pH 7.4. PN decay was observed at 320 nm.

Reaction of MnSOD and PN was also monitored at pH 8.0 and 13 °C. Under these conditions, the catalytic second-order rate constant for the reaction of MnSOD and PN was found to be 1.9 ± 0.1 × 102 M-1s-1. The rate constant for spontaneous decay of PN at pH 8.0 and 13 °C, 0.02 s-1, was an order of magnitude slower than the rate constant at pH 7.4 and 25 °C, as expected from the literature.51-52

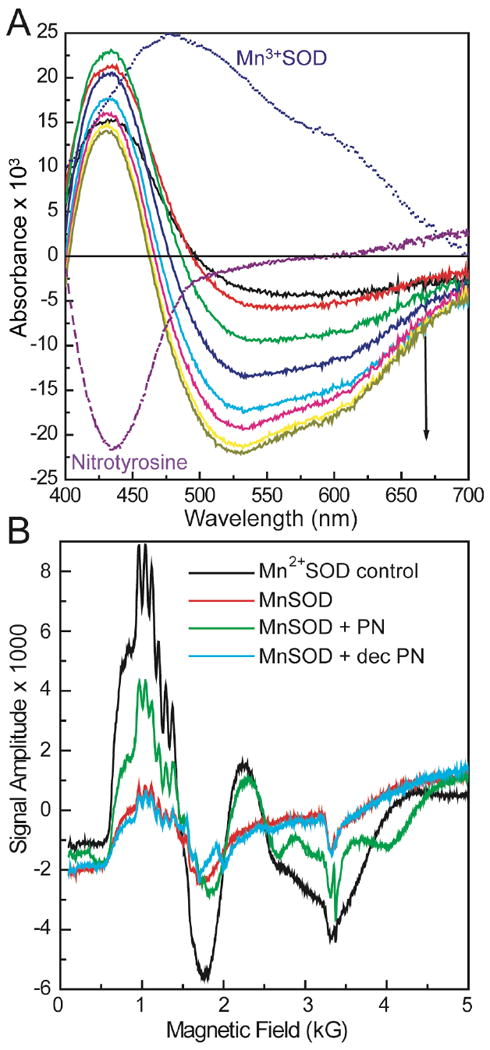

Reduction of Mn3+SOD by peroxynitrite

Reduction of the active site manganese in Mn3+SOD by peroxynitrite was observed by time-resolved difference visible spectra and EPR. The time-resolved difference spectra of the reaction of 0.1 mM MnSOD and 0.6 mM PN showed an increase in absorbance at 430 nm and a decrease in absorbance at 520 nm, at pH 8.0 and 13 °C (Figure 7A). The absorbance at 430 nm was assigned to nitrotyrosine formation as previously described. The broad negative absorbance peak at 520 nm was assigned to active site manganese in Mn3+SOD, due to its shape and characteristic shoulder at 600 nm 48. The maximum absorbance of Mn3+SOD is at 478 nm as shown in Figure 7A; however, the increase in absorbance at 430 nm caused the maximum negative absorbance to shift toward 520 nm, since this wavelength has minimal interference from nitrotyrosine absorbance. The decrease in Mn3+SOD concentration was followed by the change in absorbance at 520 nm. Under these conditions, approximately 30% of Mn3+SOD was reduced by PN.

Figure 7.

A, Time-resolved difference spectra of the reaction of 0.1 mM Mn3+SOD and 0.6 mM PN at pH 8.0 and 13°C. The decrease in Mn3+SOD absorbance was observed at 520 nm, while formation of nitrotyrosine was followed at 430 nm. Difference spectra of Mn3+SOD and nitrotyrosine (× -1 for clarity) alone are shown for comparison. B, Reduction of Mn3+SOD by PN as observed by EPR spectra. Samples were prepared by mixing 2 mM MnSOD and 20 mM PN in 0.2 M phosphate buffer with 0.1 mM DTPA at pH 8.0 on ice. Mn2+SOD control sample was prepared by reduction of 2 mM MnSOD by excess dithionite in the same buffer. 2 mM MnSOD was used as is in the same buffer as a control.

In the reaction above, we noticed that the decrease in Mn3+SOD absorbance continued after PN decay was complete (Figure S2). A half-life of 65 s was observed for the reduction of Mn3+SOD, while the half life of PN decay was only 18 s (determined from the rates of decay at 520 nm and 320 nm, respectively).

To confirm that the apparent loss of Mn3+SOD in difference spectra was due to reduction by peroxynitrite, EPR experiments were performed.48 Samples were prepared by mixing 2 mM MnSOD and 20 mM PN in 0.2 M potassium phosphate buffer with 0.1 mM DTPA at pH 8.0, on ice. An increase in Mn2+SOD EPR signal was observed after addition of PN (Figure 7B). When a sample of Mn3+SOD was mixed with the same concentration of decomposed PN, there was no significant increase in Mn2+SOD signal (Figure 7B). A control sample containing Mn2+SOD was prepared by reduction of Mn3+SOD (2 mM) by excess dithionite in 0.2 M potassium phosphate buffer with 0.1 mM DTPA at pH 8.0. The MnSOD control sample was used as is, without any oxidation step, and therefore contained around 20% Mn2+SOD as observed from EPR.

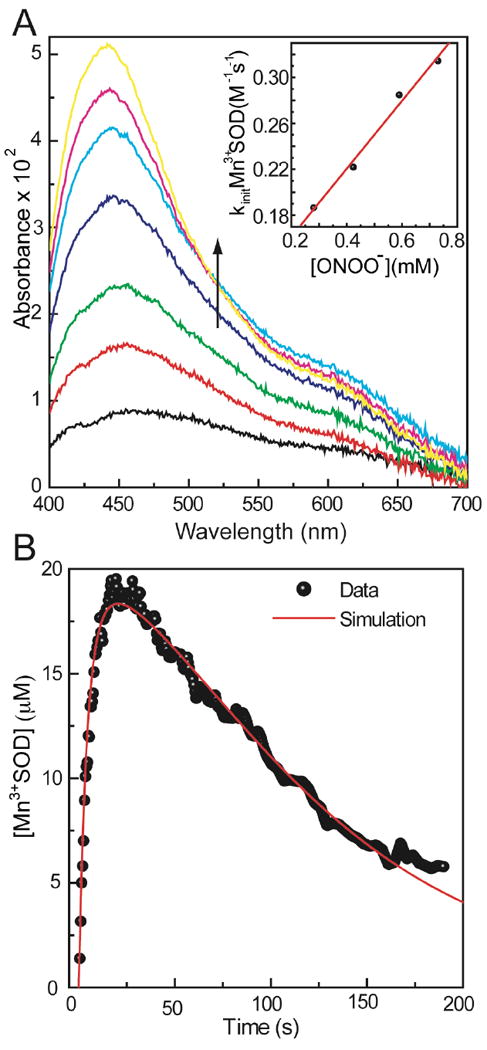

The oxidation of Mn2+SOD by peroxynitrite

When MnSOD was reduced prior to reaction with peroxynitrite, the oxidation of Mn2+SOD by peroxynitrite was observed from the increase in Mn3+SOD absorbance in the difference spectra. The reaction of 0.1 mM Mn2+SOD and 0.6 mM PN, in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer at pH 8.0 and 13 °C, resulted in an increase of a broadband absorbance peak at 450 nm with a shoulder at 600 nm (Figure 8A). This peak is attributed to nitrotyrosine and Mn3+SOD absorbance, at 430 nm and 478 nm respectively; the absorbance corresponding to Mn3+SOD was followed at 520 nm. Mn3+SOD absorbance at this wavelength increased in the first 20 s, followed by a slow decrease.

Figure 8.

A, Oxidation of Mn2+SOD by PN observed by the increase in Mn3+SOD absorbance at pH 8.0 and 13°C. The sample was prepared by mixing 0.1 mM Mn2+SOD and 0.6 mM PN in 0.1 M phosphate buffer at pH 8.0 and 13°C. The last spectrum corresponds to 20 s; the Mn3+SOD absorbance starts to decrease after this time point. Inset: Determination of the second order rate constant for Mn2+SOD oxidation by PN. Reaction of 0.1 mM Mn2+SOD and 0.4-1 mM PN in 0.1 M phosphate buffer at pH 8.0 and 13°C. The kobs is obtained from the increase in 520 nm absorbance in the first 20 s. B, Simulation for the determination of rate constants for oxidation of Mn2+SOD by PN. Raw data is from the reaction of 0.1 mM Mn2+SOD with 0.4 mM PN in 0.1 M phosphate buffer at pH 8.0 and 13°C. (Experimental data: ●, simulation: —)

Determination of the second order rate constant for oxidation of Mn2+SOD by peroxynitrite

The second order rate constant of Mn2+SOD oxidation by peroxynitrite can be obtained by measuring the rate of Mn3+SOD formation with increasing concentrations of PN. The oxidation of 0.1 mM MnSOD was observed in the presence of 0.4-1 mM PN at pH 8.0 and 13 °C. The rate constant for Mn2+SOD oxidation by PN was determined to be 3.0 ± 0.2 × 102 M-1s-1, as judged from the plot of pseudo-first order kobs obtained from the increase at 520 nm in the first 20 s of the reaction, versus PN concentration (Figure 8A, inset).

Probing mechanisms of reaction between MnSOD and peroxynitrite

In order to assess the significance of different processes to the overall reaction between MnSOD and peroxynitrite and extract kinetic parameters, we simulated the kinetics of the reaction between MnSOD and PN. The simulations were carried out by fitting model concentration versus time profiles to the experimental data. Experimental time courses were calculated for the absorbance changes at 320 nm and 520 nm by using the extinction coefficients of PN and Mn3+SOD, respectively.

Our experimental observations led us to propose that active site manganese in MnSOD can either be oxidized or reduced by peroxynitrite as shown in reactions 2 and 3. We observed a decrease in Mn3+SOD absorbance even after complete PN decay, this behavior was represented as reaction 4. In addition, the self decay of PN in buffer was described by reaction 5. These reactions (2-5) were used to model the reaction of MnSOD and PN at pH 8.0 and 13 °C.

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

Fitting of the simulated traces for both peroxynitrite decomposition and concurrent Mn2+SOD oxidation and Mn3+SOD reduction to the experimental data resulted in the rate constants shown in Table 2. The traces obtained from the simulation for the reaction of 0.1 mM Mn2+SOD with 0.6 mM peroxynitrite and the experimental trace for the same reaction are shown in Figure 8B. The coincidence of the experimental data to the simulated trace indicates that the calculated rate constants are a good representation of the actual reaction rates in the proposed mechanism.

Table 2.

The rate constants for the reactions 2-4 obtained from simulation and experimentally observed when available (ND: Not Determined).

| Rate constant | Rate obtained from Simulation | Experimentally observed Rate |

|---|---|---|

| k2 | 200 M-1s-1 | 300 M-1s-1 |

| k3 | 550 M-1s-1 | 100* M-1s-1 |

| k4 | 0.01 M-1s-1 | ND |

| k5 | 0.02 M-1s-1 | 0.02 M-1s-1 |

Estimated from Figure S1.

Tyr2, Tyr9 and Tyr11 were on the same peptide after trypsin digestion but the MS/MS data indicates the nitration is on Tyr9 or Tyr11 (Figure S5).

Peroxynitrite concentrations for these samples were optimized to give comparable yields; in addition samples with and without azide have the same peroxynitrite concentration.

The rate constant obtained from the simulation for oxidation of Mn2+SOD by PN is in agreement with the experimentally observed rate constant, 200 M-1s-1 (simulation) versus 300 M-1s-1 (experimental). In addition, as the overall catalytic rate constant is expected to be close to that of the slower step, oxidation of Mn2+SOD by PN, it is also in agreement with the simulation (kcat =190 M-1s-1).

DISCUSSION

Selectivity of MnSOD nitration

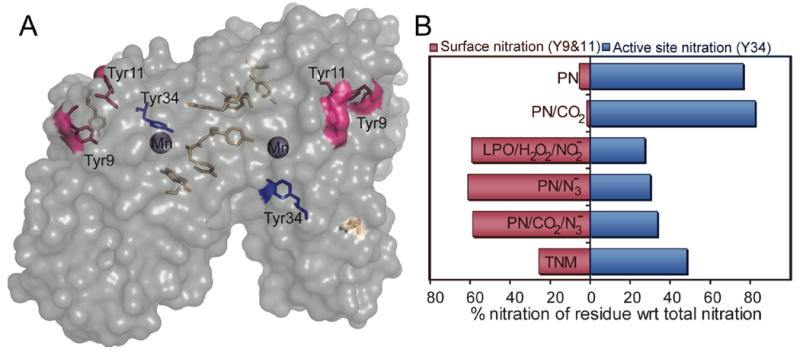

The results clearly show that the pattern of MnSOD nitration, as defined by the relative sensitivity of each tyrosine residue toward nitration, is strongly dependent on the nature of the nitrating agent. Each MnSOD monomer has seven tyrosine residues, but only three of these residues, Tyr9, Tyr11 and Tyr34, proved to be susceptible to significant nitration (Table 1). Tyr9 and Tyr11 have substantial solvent accessibility, while Tyr34 is deeply buried by the subunit interface, and immediately adjacent to the active site manganese (Figure 9A)45,53. All three of these residues are conserved between E. coli and human MnSOD.44-46

Figure 9.

A, Surface accessibility of residues in one of the two subunits of E. coli MnSOD. Tyrosine residues are highlighted with different colors labeled with the residue number. The accessible surface of MnSOD is shown as transparent gray, and the accessible surface of each tyrosine residue is reflected on the surface with the color of the corresponding residue. Active site manganese ion is shown in purple. Created by PyMol program using crystal structure (PDB ID: 1VEW). Solvent accessibility of each tyrosine residue calculated by ASAView is as follows: Tyr2, 9.2; Tyr9, 20.6; Tyr11, 29.9, Tyr34, 6.1; Tyr173, 2.8; Tyr174, 0.5; Tyr184, 0.1 %. cf. references 45,53. B, Relative nitration of residues Tyr34, Tyr9 and Tyr11 with respect to total nitration in MnSOD nitrated under different conditions. The relative amount of nitrotyrosine at each locus was determined by comparing the area under the assigned peaks due to absorbance at 355 nm during LC-MS/MS. MnSOD was nitrated by: PN in the absence and presence of azide and CO2, LPO with H2O2 and NO2-, and TNM.

The patterns of active site (Tyr34) and surface (Tyr9 and Tyr11) tyrosine nitration observed under various reaction conditions are presented graphically in Figure 9B. Tyrosine nitration patterns were determined by making use of the nitrotyrosine chromophore at 355 nm (or nitrotyrosinate at 430 nm). This UV absorbance allowed both the unambiguous identification of peptides in the digest that contained nitrated tyrosine residues and an accurate quantification of relative amounts of nitrotyrosine-containing peptides. To our knowledge this is the first quantitative analysis of changes in nitration patterns due to different agents of nitration. The absorption spectrum of each peak in the chromatogram was also obtained in order to avoid false positives and to facilitate the differentiation of tryptophan nitration from tyrosine nitration. In addition, the chromatogram of the molecular ions identified from the tandem mass spectral data as nitrated peptides matched the absorbance chromatogram at 355 nm, confirming our assignments (Figures S4-S7).

Significantly, Tyr34 proved to be hypersensitive toward nitration only when peroxynitrite was the nitrating agent. By contrast, freely diffusing •NO2 produced from peroxidase-catalyzed oxidation of nitrite ion resulted primarily in the nitration of the surface accessible tyrosines, Tyr9 and Tyr11. We also found that MnSOD is generally resistant to nitration by freely diffusing •NO2, since nitration of MnSOD required higher concentrations of H2O2 and NO2- compared to other proteins such as lysozyme and myoglobin.54-55 MnSOD nitrated by tetranitromethane (TNM) had a different selectivity from all other conditions, probably due to a distinctly different mechanism of nitration by TNM. The selectivity of nitration by TNM is not well understood and may result from binding of TNM to the protein.56

Mechanism and kinetic modeling of the reaction between MnSOD and Peroxynitrite

Our results show that MnSOD catalyzed the decomposition of peroxynitrite with a second order rate constant kcat = 9.3 ± 0.9 × 102 M-1s-1 at pH 7.4 and 25°C (Figure 6). Thus, this reaction is significantly slower than those of heme proteins, such as myoglobin (1.03 × 104 M-1s-1),54 or model compounds such as iron porphyrins (106 – 107 M-1s-1).57-58 Accordingly, MnSOD is not an efficient catalyst for PN decomposition.50,52,57

As isolated, MnSOD is a mixture of Mn2+ and Mn3+ oxidation states with the latter predominating. During the reaction of MnSOD with PN, the 520 nm absorbance due to Mn3+SOD was observed to decrease rapidly (Figure 7A) and the EPR resonance characteristic of Mn2+ was observed to increase (Figure 7B). Clearly, the Mn3+ center is reduced to Mn2+ by PN (kred = 550 M-1s-1, Table 2). We have reported similar behavior for MnTexaphrin, while MnIII porphyrins are oxidized by PN to the oxoMnIV state.59-60 We did not observe any indication of Mn3+SOD oxidation to MnIV by PN either in the time resolved difference spectra or in the EPR spectra. In addition, no reduction of Mn3+SOD was observed with decomposed PN solutions, indicating that other reducing agents such as nitrite ion or traces of hydrogen peroxide are not involved in the observed conversion of Mn3+ to Mn2+. The reduction of Mn3+SOD by PN is thermodynamically feasible, since the reduction potential of •ONOO (E◦’(•ONOO/ONOO-) = 0.43 ± 0.1 V) is close to the Mn3+/Mn2+ redox couple in MnSOD (Em = 0.29 ± 0.02 V).61-62 While the difference in redox potentials gives a slightly positive free energy (~ 2.3 kcal), this barrier is offset by the decay of •ONOO to form more stable products, •NO and O2.

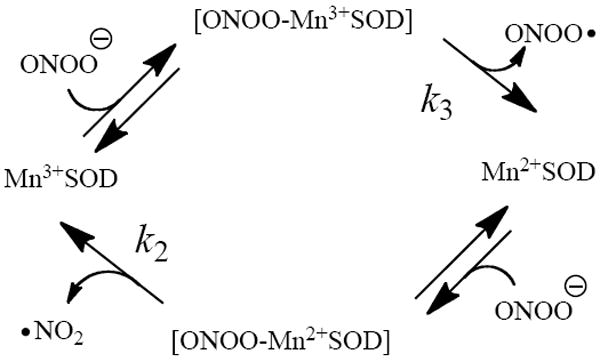

Peroxynitrite was also found to oxidize Mn2+SOD to Mn3+SOD, as indicated by the increase in the signature absorbance at 520 nm (Figure 8A). This reaction is very favorable due to the high reduction potential of PN to •NO2 [E◦’(ONOO-, 2H+/•NO2) = 1.4 ± 0.1 V]. Together these observations show that the catalytic reaction cycle for MnSOD and PN is similar to that of its reaction with its natural substrate, •O2-,63 wherein the active site manganese cycles between Mn2+ and Mn3+ oxidation states (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

The abbreviated catalytic cycle for MnSOD reaction with peroxynitrite

The observed reaction kinetics were modeled well by the mechanism in Scheme 1 using eqs 2-5 above (Figure 8B). The inclusion of eq 4 was necessary to account for the slow loss of Mn3+SOD after the conclusion of PN decay (Figure S1). The rate constants obtained by fitting eqs 2-5 to our experimental data are in close agreement with the experimentally observed values. In addition, the catalytic rate constant extracted from the kinetic fit (kcat = 300 M-1s-1) was identical to the observed rate of oxidation of Mn2+SOD by PN (k2 = 300 M-1s-1), confirming that this step is rate-limiting in the catalytic cycle. Thus, reduction of Mn3+SOD by PN must have a larger rate constant as predicted from the simulation. Based on these results we conclude that Scheme 1 is a good description of the actual reactions of PN with MnSOD.

Role of the Active Site Manganese in Nitration of MnSOD

Reaction flux analysis using kcat = 9.3 ± 0.9 × 102 M-1s-1 for peroxynitrite decomposition by MnSOD indicates that only 10% of PN decay goes through the catalytic pathway. Still, PN selectively nitrated Tyr34. Since the yield of nitration was less than 10% of the amount of PN used, all the nitration of Tyr34 could result from the active site manganese reaction with PN (Figure S8). However, the kinetics of nitrotyrosine formation did not agree well with this simple model of MnSOD nitration. Significantly, the rate of nitrotyrosine formation was found to be almost linear with time, displaying apparent zero-order kinetics over the first 10-15 s (Figure S1). This result indicates that the mechanism of MnSOD nitration is more complicated than predicted by a simple manganese-catalyzed pathway. The appearance of zero-order kinetics in Tyr34 nitration by PN could result from saturation behavior of some kind, such as peroxynitrite anion binding in the approach channel to the active site manganese, as will be discussed further below.

The effect of CO2 on the mechanism and pattern of MnSOD nitration by peroxynitrite

The susceptibility of Tyr34 toward nitration by peroxynitrite is intriguing considering its position in the active site and its low solvent accessibility compared to Tyr9 and Tyr11. The manganese-catalyzed pathway for generating •NO2 at the active site (Scheme 1) could reasonably explain this selectivity in the absence of CO2. However, the key observation that Tyr34 hypersensitivity in the PN-mediated nitration is retained in the presence of excess CO2 requires another explanation. The reaction of CO2 with peroxynitrite is fast (k = 3 × 104 M-1s-1), resulting in the formation of •NO2 and •CO3- in the medium from the facile decomposition of the initially-formed adduct, 1-carboxylato-2-nitrosodioxidane (ONOOCO2-) (Scheme 2). 51-52,64-65 As is shown in Figure 2, the observed rate of tyrosine nitration strictly followed the rate of CO2-catalyzed PN decay and was much too fast to be caused by the manganese-catalyzed pathway in Scheme 1. Moreover, the efficiency of tyrosine nitration increased by more than an order of magnitude with CO2 present. Indeed, 10 μM MnSOD afforded a 23% yield of nitrated tyrosines with only a 1.3-fold excess of PN, as compared to only 1.3% in the absence of CO2 (Figure 2). Since the yields of •NO2 and •CO3- from cage escape are known to be 20-35% with respect to peroxynitrite,66-67 the yield of nitrated tyrosine in MnSOD must be nearly quantitative with respect to these radical species.68-70 A flux analysis of the various pathways for PN decomposition under the conditions used showed that 96% of PN decay will proceed via CO2 catalyzed decay and only 0.2% via the Mn-catalyzed route. The remainder is spontaneous PN decay. Accordingly, the kinetics indicate a diminished role of the Mn-catalyzed pathway in the presence of CO2. Thus, since only a 30% excess of peroxynitrite with respect to MnSOD was used in these CO2-containing runs, nearly all of the nitration must have occurred via the CO2-dependent route.

Scheme 2.

Flux analysis of reactions leading to MnSOD nitration by peroxynitrite in the presence of excess CO2.65 The relative flux of peroxynitrite reacting with CO2 is 96.3 %, that decomposing via protolysis is 3.5 % and the flux reacting directly with MnSOD is 0.2 %, as obtained from known and measured rate constants, cf. references 51, 52, 64 and 65.

It was our initial expectation that •NO2 formed by the CO2 pathway would behave similarly to •NO2 produced in the medium by the peroxidase-mediated oxidation of nitrite ion. Clearly, a pathway involving freely diffusing •NO2 cannot explain the enhanced nitration efficiency and the high selectivity for Tyr34 observed for PN-CO2. However, a specific role for •CO3- could explain these results. We suggest that the high efficiency of PN-CO2 and the hypersensitivity of Tyr34 toward nitration are due to selective oxidation of Tyr34 by the carbonate radical anion.

Notably, tryptophan residues usually react 10 times faster with •CO3- than with tyrosine.70 Indeed, Trp32 in Cu-ZnSOD is selectively oxidized and nitrated by PN-CO2.71-72 Further, the peroxidase activity observed with Cu-ZnSOD has been attributed to the carbonate radical anion.73-76

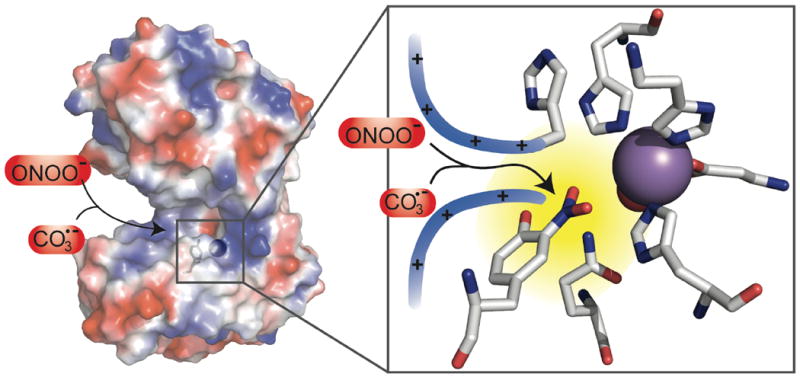

Cationic amino acid side chains and an anionic binding site in the active site channel of MnSOD have been proposed to enhance the very rapid kinetics of superoxide ion dismutation (Figure 10). It is known that anions are attracted to the active site because of a positive electrostatic potential caused by arginine and lysine residues leading the to active site.77-79 These same effects could also provide a rationale for the high reactivity of Tyr34 to anionic oxidants seen here. To our knowledge, a specific role for •CO3- in MnSOD damage has not been suggested before. However, •CO3- is well known to be an efficient oxidant for phenols (E◦’(•CO3-, H+/ HCO3-) = 1.78 V).66,69-70 The bicarbonate O-H bond dissociation energy is ~107 kcal/mol.68,80-81 Thus, facilitated diffusion of •CO3-, acting as a surrogate for superoxide anion, could lead to the selective formation of a phenoxy radical at Tyr34. Although such a specific role for •CO3- is an inference based on the observed kinetics, the results make it unlikely that either PN or •NO2 are the immediate culprits in the presence of CO2.

Figure 10.

Left hand panel shows the surface of MnSOD dimer defined by a probe atom of radius 1.4 Å and colored according to electrostatic potential (blue, positive; red, negative; extremes of color correspond to 12kT), created by PyMol (PDB ID: 1VEW). The arrows from ONOO- and •CO3- follow the substrate access channel to the active site. Right hand panel shows nitration of Tyr34 in the active site; the active site manganese is shown as a purple sphere, red sphere denotes oxygen of the OH- coordinated to the active site manganese. cf. reference 45.

The effect of azide on the pattern of MnSOD nitration

The pattern of MnSOD nitration by peroxynitrite also responded to the presence of azide ion, an inhibitor that is known to bind to active site manganese.48 Addition of sodium azide resulted in a significant decrease in Tyr34 nitration whereas the extent of nitration of the Y34F MnSOD variant was unaltered (Figures 3 and 9). At the concentrations used, only 10-30 % of the active site manganese would be bound to azide, (KD = 7.2 mM).48 Accordingly, the observed azide inhibition of Tyr34 nitration cannot be attributed entirely to azide ligation to manganese. However, a secondary anion binding site near the MnSOD active site, involving Tyr34, has been described by Tabares et al,82-83 and a similar site for azide binding in the highly homologous FeSOD has been directly observed with NMR by Miller et al.84 Significantly, the same azide-induced decrease in Tyr34 nitration selectivity was observed in the presence of CO2. These effects could be explained by azide interference with access to the active site by PN anion and carbonate radical anion. While the possible oxidation of azide to •N3 cannot be discounted completely, the reaction of PN with azide appears to be far too slow to affect the reactivity under our conditions (k = 1.2 M-1s-1).85 Also, since •N3 is a neutral radical, like •NO2, it would be expected to have a similar selectivity, targeting nitration of the most solvent exposed residues, Tyr9 and Tyr11.

Biological Significance

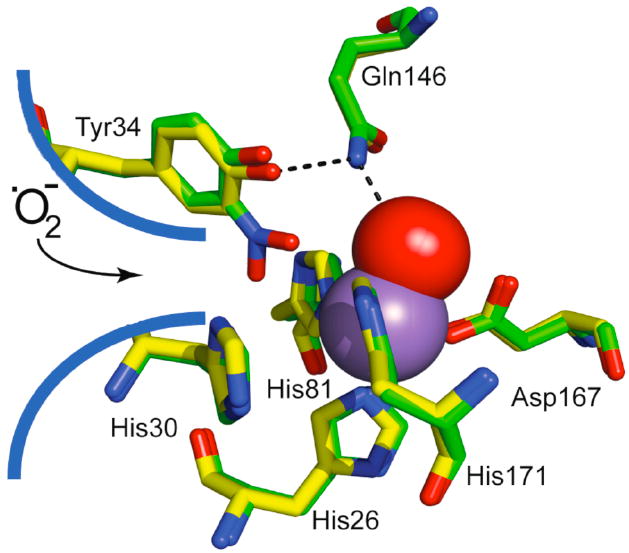

The nitration of Tyr34 of mitochondrial MnSOD under conditions of oxidative and nitrosative stress in vivo and the concomitant loss of SOD activity appear to be significant indicators of pathology.4,16 However, nitrated MnSOD is more than an indicator of oxidative stress, as loss of MnSOD activity was observed as an early event during ischemia/reperfusion injury.11 The loss of activity of nitrated MnSOD indicates that the target of nitration is Tyr34.25-26 In fact, specific nitration of Tyr34 in MnSOD has recently been detected in atherosclerotic coronary artery disease.86 Emphasizing the role of Tyr34 nitration on the enzyme activity, MnSOD prepared with a genetically encoded nitrotyrosine at position 34 has been shown by Chin et al. to lose 97% of its activity.87 The recently published crystal structure of nitro-Tyr34-MnSOD shows that nitro-Tyr34 blocks access to the active site manganese and may also cause a weakening of a hydrogen bond network (Figure 11).88 Our results with purified protein showing a highly diagnostic pattern of nitration at Tyr34 suggest that MnSOD nitration in vivo evolves directly from the formation of peroxynitrite within cells.

Figure 11.

The structure of the active site region of nitrated (green, PDB ID: 2ADP) superimposed onto unmodified (yellow, PDB ID: 1VEW) MnSOD. The inner shell ligands His26, His81, His171, Asp167 are shown. The His30 and Tyr34 residues are denoted as the gateway residues since they reside at the end of the substrate access channel toward active site manganese; nitration of Tyr34 blocks the entrance of •O2- to the active site. cf. references 45, 89.

Significantly, the conditions of MnSOD nitration by peroxynitrite in the presence of CO2 closely resemble conditions in vivo. Typical cellular concentrations of CO2 are ~1.3 mM, in equilibrium with 14-25 mM bicarbonate, and peroxynitrite is thought to be formed at low μM concentrations.5,68,75 We propose that under these conditions the carbonate radical anion formed from the PN-CO2 reaction specifically oxidizes Tyr34 to a phenoxy radical that rapidly recombines with even traces of •NO2 to form MnSOD nitrated at Tyr34. This radical recombination step is known to be very fast, near the diffusion limit. The role of peroxynitrite and physiologically relevant concentrations of CO2 in the production of carbonate radical anion has not previously been considered as a specific vector for MnSOD damage.

MnSOD is implicated in the cell cycle by controlling the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS); pro-apoptotic genes p53 and c-Myc induce apoptosis via suppression of MnSOD resulting in an increase in ROS.41 Since the nitration of MnSOD also results in loss of activity, there is a clear implication that peroxynitrite formation may result in the induction of apoptosis. MnSOD nitration and inactivation can also affect •NO signaling by limiting the bioavailability of •NO due to increase in •O2- levels.89 In addition, MnSOD has been found to be phosphorylated and dephosphorylation resulted in an increase in activity of MnSOD. It has been suggested that phosphorylation of MnSOD occurred at Tyr34 interfering with activity.90

CONCLUSIONS

The nitration and inactivation of MnSOD described here provide important clues regarding the mechanism of the analogous reaction in vivo. We have shown that the mechanism of the reaction between peroxynitrite and MnSOD is similar to its reaction with •O2-, sharing the feature that the active site manganese gets both oxidized and reduced by peroxynitrite using the Mn2+/Mn3+ redox couple. The selectivity of MnSOD nitration with different agents was determined by identification and quantification of each nitrated tyrosine residue. MnSOD nitration mediated by peroxynitrite resulted in selective nitration of the tyrosine residue close to the active site manganese, Tyr34; while nitration by •NO2 leads to nitration of the most solvent exposed residues, Tyr9 and Tyr11. The susceptibility of Tyr34 toward nitration by peroxynitrite in the absence and presence of CO2 suggests that the selectivity of MnSOD nitration is not only a result of the reaction between active site manganese and peroxynitrite, but also the ability of active site to attract anions such as •CO3-. We also investigated the changes in activity of MnSOD under different conditions and observed that loss of activity in nitrated MnSOD is exclusively due to nitration of Tyr34. The lack of activity of nitrated MnSOD under disease conditions suggests that nitration of MnSOD observed under oxidative stress is due to peroxynitrite directly or via its reaction with CO2.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

Sodium azide, 3-nitrotyrosine, and tetranitromethane (TNM) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Diethylenetriaminepentaacetatic acid (DTPA) was purchased from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA). Bovine lactoperoxidase (LPO) was purchased from Worthington. Potassium phosphate dibasic, potassium phosphate monobasic, sodium bicarbonate, and sodium nitrite were purchased from EM Scientific. All other reagents were analytical-grade.

As previously described, peroxynitrite was synthesized from hydrogen peroxide and nitrous acid using a p250i syringe pump (KD scientific) via the quenched flow method.91-93 Hydrogen peroxide was reduced to less than 5 mol % of PN by treatment with manganese dioxide (10 mg/mL at 4 °C for 30 min). Finally, particulate MnO2 was removed by passing the solution through a 0.2 μm Supor membrane syringe filter (Pall Corporation). Hydrogen peroxide was assayed with a Cayman Chemicals kit.

MnSOD for mechanistic experiments was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). MnSOD for HPLC-ESI-MS/MS experiments was obtained as described: Escherichia coli strain AB 2463/pDT1-5, which contains an antibiotic resistance plasmid carrying the MnSOD structural gene, was a generous gift from Dr. Sam Dukan (Laboratoire de Chimie Bacterienne, France).94 E. coli pDT1-5 was grown at 37 °C in 6 L of 2X LB medium supplemented with 20 μM of MnSO4•H2O and 100 μg/mL ampicillin. Protein expression was induced by the addition of N,N′-dimethyl-4,4′-bipyridinium dichloride (Sigma) after the cultures have reached an absorbance of 0.4 at 600 nm.95 Some Escherichia coli MnSOD and the Y34F variant were purified as previously described.48,96 All MnSOD samples were purified by an EconoPac® 10 DG Column (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) or the buffer was exchanged by dialysis using D-Tube™ Dialyzer Midi units from Novagen. MnSOD concentration was determined by the extinction coefficient at 280 nm ε280 = 8.66 × 104 M-1cm-1.48,97 All buffers and solutions were degassed under argon for at least 20 min directly prior to use to deplete dissolved carbon dioxide. Solutions containing CO2 were prepared by addition of the appropriate amount of 0.5 M HCO3- in the corresponding phosphate buffer and equilibration after mixing for 5 min.98-99 All ultraviolet/visible (UV/Vis) spectroscopy studies were done using an Agilent 8453 UV-visible Spectroscopy System.

Stopped-Flow Kinetics

The rates of nitrotyrosine formation and PN decomposition were studied by stopped-flow spectrophotometry (Hi-tech Scientific SF-61 DX2). Solutions of wild type or Y34F variant MnSOD (20-30 μM) in 0.5 M phosphate buffer and 0.1 mM DTPA at pH 7.4 were mixed with PN (0.02-2 mM) in 0.01 M NaOH using the stopped-flow system; the concentration of PN used was based on the minimal amount required to observe the reaction products. Sodium azide (2-4 mM) was added to the MnSOD solutions prior to this mixing as required. The stoichiometry of MnSOD, PN mixing was 1:1 or 1:4. Solutions were analyzed by both diode-array and single-wavelength detection methods. When using the diode-array mode, data was recorded for all wavelengths between 300 and 600 nm. PN decay was observed at 320 nm due to interference by nitrotyrosine absorption at 302 nm; the extinction coefficient of PN at 320 nm was determined to be 1370 M-1cm-1 from its ratio with the known extinction coefficient at 302 nm (1670 M-1cm-1).66 For both methods of detection, nitrotyrosine formation was observed at 430 nm with the extinction coefficient 4400 M-1cm-1.47 Data was recorded for the first 30 s of the reaction, with 300 scans being taken over this period. The curves presented represent an average of at least 4 individual experiments. The data was analyzed with the KinetAsyst 3 software control package.

Oxidation and Reduction of MnSOD by peroxynitrite

Stopped-flow studies were carried out as explained above, with the exception that a higher concentration of MnSOD was necessary (0.1 mM) to observe the Mn3+SOD chromophore. In addition, as the studies were conducted at pH 8.0 and 13 °C, where PN decay was slower; data was recorded for 200 s of the reaction. Changes in the Mn3+SOD concentration during the reaction were determined by using the extinction coefficient at 520 nm (ε520 nm = 750 M-1cm-1), calculated from the ratio of the absorbance at 520 nm to its known absorption maxima at 478 nm (ε520 nm = 750 M-1cm-1).48 Mn3+SOD samples were prepared by dialysis against 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer at pH 8.0. Mn2+SOD samples were prepared by reduction using excess dithionite. Excess dithionite was then removed under argon with an EconoPac® 10 DG Column equilibrated with 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer at pH 8.0 with 0.1 mM DTPA degassed with argon. Mn2+SOD collected from the column was used immediately, to prevent any oxidation in air.

EPR samples were prepared by dialysis of MnSOD against 0.2 M potassium phosphate buffer with 0.1 mM DTPA at pH 7.1 (buffer A). Peroxynitrite (20 mM) was added directly to MnSOD (2 mM) in buffer A, on ice. The final pH was determined to be 8.0. The MnSOD samples were either frozen immediately, or incubated for 30 min on ice. Samples were kept in liquid nitrogen prior to EPR analysis. A Mn3+SOD control sample was also dialyzed against buffer A; prior to freezing pH of the sample was adjusted, by addition of 1 M NaOH, to pH 8.0. A Mn2+SOD control sample was prepared by addition of excess dithionite (7 mM) to MnSOD (2 mM), that was dialyzed against buffer A; then pH was adjusted to pH 8.0 by addition of 1 M NaOH. Decomposed peroxynitrite was obtained by addition of 0.1 M of HClO4 to the PN solution, and incubation at room temperature to allow complete decay of PN. After adjusting the pH of decayed PN solution to pH 7.0 and adding an equivalent amount of decayed PN (20 mM) to MnSOD (2 mM), previously dialyzed against buffer A, the pH of the final solution was adjusted to pH 8.0 with 1 M NaOH. EPR spectra were collected on a Bruker ESP300e X-Band spectrometer. EPR spectra were collected at 5 K and 9.4 GHz using 20 mW power and 20 G modulation at 100 kHz with center field at 3100 G and a sweep width of 6000 G.

Liquid Chromatography and Tandem Mass Spectrometry (HPLC-ESI-MS/MS)

Samples for HPLC-MS/MS analysis were prepared accordingly: 10 μM MnSOD was nitrated by 0.3 mM (or 35 μM in the presence of CO2) PN using the stopped-flow apparatus as a mixing device in the presence and absence of 1.5 mM azide and/or 0.175 mM CO2 (in equilibrium with 2 mM HCO3-) in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer with 0.1 mM DTPA at pH 7.4 and 25 °C. MnSOD and PN was allowed to react for 30 s for the nitration to reach conclusion; in the presence of CO2 the reaction was completed in 2-4 s. In addition, 10 μM MnSOD was nitrated by 0.05 μM LPO in the presence of 2 mM NaNO2 and 2 mM H2O2 in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer at pH 7.5 and 25 °C for 5 min. MnSOD (10 μM) was also nitrated by 1 mM TNM in 0.1 M Tris-HCl with 0.1 M KCl at pH 8.0 for 30 min. The conditions of MnSOD nitration, e.g. peroxynitrite concentration, was optimized to have comparable nitration yields (Table 1) to ensure the change selectivity of nitration is only dependent on the nitrating agent.

The samples were analyzed using the following conditions and machinery: Samples were extensively dialyzed against 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate before digestion. The protein was digested overnight with modified trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI), at 1:50 (protease:protein) ratio, in the presence of 0.1% RapiGest™ SF (Waters). RapiGest was removed after complete digestion, by acid treatment and centrifugation, according to manufacturer’s instructions. The trypsinized peptides were analyzed by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-ESI-MS/MS). An Agilent 1100 HPLC system with an auto injector and variable wavelength detector (Agilent, Wilmington, DE) with Proteo C18 (2 mm × 150 mm) column from Phenomenex was used for peptide separation. A LCQ DECA XP PLUS ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Finnigan, San Jose, CA) was used for mass spectroscopic analysis. A post column delivery of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) fix solution (75% acetic acid in methanol) at 1μL per minute flow was made to eliminate the ion suppression from TFA. A Surveyor photodiode array (PDA) detector from ThermoFisher was set to collect data from 200 nm to 600 nm wavelengths. Three UV wavelength traces were also collected: 214 nm for all peptides, 260 nm for tyrosine containing peptides and 355 nm for nitrated tyrosine containing peptides. A survey full MS scan was acquired from 300 to 1800 m/z range in LCQ DECA XP PLUS ion trap mass spectrometer from ThermoFisher. An automatic gain control (AGC) target of 5×107 and 100 ms maximum ion accumulation time were used. The 3 most intense ions in full MS scan were fragmented and analyzed at 5000 signal threshold, 2×107 AGC target and 100 ms maximum ion accumulation time, 3 amu isolation width and 30 ms activation at 35% normalized collision energy. Dynamic exclusion is enabled to exclude from fragmentation ions that had been already selected for MS/MS in previous 30 sec. All MS and MS/MS scans were collected in centroid mode. All MS/MS spectra were analyzed using the SEQUEST program, and the program Qual Browser was used to help identify the fragments. The relative amount of nitration of each residue was obtained from the chromatogram at 355 nm by the ratio of the area under the corresponding peak with respect to total area. The relative nitration of tryptophan residues was corrected using the relative 6-nitrotryptophan extinction coefficient with respect to nitrotyrosine extinction coefficient at 355 nm 47. Additionally, the percent of nitration in total protein was obtained by ESI-MS of intact protein dialyzed against water.

Activity of MnSOD after Nitration with Peroxynitrite

Samples for activity determination were prepared by nitration of 10 μM MnSOD with 0.3-1 mM PN in the absence or presence of 2 mM CO2, or nitration of 8 μM MnSOD with 0.2-0.8 mM PN in the absence or presence of 1.5 mM azide, in the stopped-flow apparatus, in 0.2 M potassium phosphate with 0.1 mM DTPA at pH 7.4. MnSOD solutions were first dialyzed against 50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.0, and then diluted in the same buffer, to give a final concentration of 0.02 μM for the superoxide dismutase assay. The protocol for the Superoxide Dismutase Assay from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI) was followed for activity measurements after PN treatment of MnSOD solutions as described above. The activities of nitrated samples were normalized against the activity of unmodified MnSOD under the same conditions.

Computer Program Analysis

Pymol was used to create images of proteins. Berkeley Madonna 8.0.1 was used to simulate kinetic models of the stopped-flow experiments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for support of this research by the National Institutes of Health (2R37 GM036298). We thank Prof. D. Touati and Dr. Sam Dunken for E. coli with the plasmid pDT1.5. We thank Saw Kyin and Henry Shwe for their assistance in HPLC-MS/MS experiments. We thank Dr. Melinda Baker for help with protein purification and Dr. Alexei Tyryshkin for help with EPR experiments.

Footnotes

Supporting information Available. Kinetic plots of Mn3+SOD reduction by peroxynitrite, the HPLC trace of all the samples followed at 355 nm, the tandem mass spectra of nitrated tyrosine and tryptophan residues and kinetic plots of MnSOD nitration. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

References

- 1.Beckman JS. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;484:114–116. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ischiropoulos H. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;484:117–121. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrer-Sueta G, Radi R. ACS Chem Biol. 2009;4:161–177. doi: 10.1021/cb800279q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abello N, Kerstjens HAM, Postma DS, Bischoff R. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:3222–3238. doi: 10.1021/pr900039c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radi R. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4003–4008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307446101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ischiropoulos H. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;356:1–11. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reynolds MR, Berry RW, Binder LI. Biochemistry. 2007;46:7325–7336. doi: 10.1021/bi700430y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ascenzi P, di Masi A, Sciorati C, Clementi E. BioFactors. 2010;36:264–273. doi: 10.1002/biof.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reyes JF, Reynolds MR, Horowitz PM, Fu YF, Guillozet-Bongaarts AL, Berry R, Binder LI. Neurobiology of Disease. 2008;31:198–208. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wattanapitayakul SK, Weinstein DM, Holycross BJ, Bauer JA. FASEB J. 2000;14:271–278. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cruthirds DL, Novak L, Akhi KM, Sanders PW, Thompson JA, MacMillan-Crow LA. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2003;412:27–33. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(03)00039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayer B, Hemmens B. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:477–481. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01147-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halliwell B, Zhao K, Whiteman M. Free Radical Res. 1999;31:651–669. doi: 10.1080/10715769900301221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Espey MG, Miranda KM, Feelisch M, Fukuto J, Grisham MB, Vitek MP, Wink DA. Reactive Oxygen Species: From Radiation to Molecular Biology. 2000;899:209–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anggard E. Lancet. 1994;343:1199–1206. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pacher P, Beckman JS, Liaudet L. Physiological Reviews. 2007;87:315–424. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zielonka J, Sikora A, Joseph J, Kalyanaraman B. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:14210–14216. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.110080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zielonka J, Sikora A, Joseph J, Kalyanaraman B. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:LE16–LE16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.110080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jourd’heuil D, Lancaster JR, Fukuto J, Roberts DD, Miranda KM, Mayer B, Grisham MB, Wink DA. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:LE15–LE15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.L110.110080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill BG, Dranka BP, Bailey SM, Lancaster JR, Darley-Usmar VM. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:19699–19704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.101618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bian K, Gao ZH, Weisbrodt N, Murad F. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5712–5717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Dalen CJ, Winterbourn CC, Kettle AJ. Biochem J. 2006;394:707–713. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roncone R, Barbieri M, Monzani E, Casella L. Coord Chem Rev. 2006;250:1286–1293. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cape JL, Hurst JK. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;484:190–196. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacMillan-Crow LA, Crow JP, Kerby JD, Beckman JS, Thompson JA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:11853–11858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nilakantan V, Halligan NLN, Nguyen TK, Hilton G, Khanna AK, Roza AM, Johnson CP, Adams MB, Griffith OW, Pieper GM. Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2005;24:1591–1599. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo W, Adachi T, Matsui R, Xu SQ, Jiang BB, Zou MH, Kirber M, Lieberthal W, Cohen RA. American Journal of Physiology Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2003;285:H1396–H1403. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00096.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Comhair SAA, Xu WL, Ghosh S, Thunnissen FBJM, Almasan A, Calhoun WJ, Janocha AJ, Zheng LM, Hazen SL, Erzurum SC. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:663–674. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62288-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koeck T, Fu XM, Hazen SL, Crabb JW, Stuehr DJ, Aulak KS. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:27257–27262. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401586200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bayir H, Kagan VE, Clark RSB, Janesko-Feldman K, Rafikov R, Huang ZT, Zhang XJ, Vagni V, Billiar TR, Kochanek PM. J Neurochem. 2007;101:168–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamakura F, Kawasaki H. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta-Proteins and Proteomics. 2010;1804:318–325. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rahman NA, Mori K, Mizukami M, Suzuki T, Takahashi N, Ohyama C. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:3603–3610. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weisiger RA, Fridovich I. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:4793–4796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller AF. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2004;8:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Landis GN, Tower J. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 2005;126:365–379. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dumont M, Wille E, Stack C, Calingasan NY, Beal MF, Lin MT. FASEB J. 2009;23:2459–2466. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-132928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kowluru RA, Atasi L, Ho YS. Investigative Ophthalmology and Visual Science. 2006;47:1594–1599. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doyle T, Bryant L, Batinic-Haberle I, Little J, Cuzzocrea S, Masini E, Spasojevic I, Salvemini D. Neuroscience. 2009;164:702–710. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.MacMillan-Crow LA, Crow JP, Thompson JA. Biochemistry. 1998;37:1613–1622. doi: 10.1021/bi971894b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamakura F, Taka H, Fujimura T, Murayama K. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14085–14089. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pani G, Koch OR, Galeotti T. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:1002–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Souza JM, Daikhin E, Yudkoff M, Raman CS, Ischiropoulos H. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;371:169–178. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ischiropoulos H. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;305:776–783. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00814-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Borgstahl GEO, Parge HE, Hickey MJ, Beyer WF, Hallewell RA, Tainer JA. Cell. 1992;71:107–118. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90270-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Edwards RA, Baker HM, Whittaker MM, Whittaker JW, Jameson GB, Baker EN. J Biol Inorg Chem. 1998;3:161–171. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wagner UG, Pattridge KA, Ludwig ML, Stallings WC, Werber MM, Oefner C, Frolow F, Sussman JL. Protein Sci. 1993;2:814–825. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560020511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crow JP, Ischiropoulos H. Nitric Oxide, Pt B. 1996;269:185–194. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)69020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Whittaker JW, Whittaker MM. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:5528–5540. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jackson TA, Karapetian A, Miller AF, Brunold TC. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:12477–12491. doi: 10.1021/ja0482583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quijano C, Hernandez-Saavedra D, Castro L, McCord JM, Freeman BA, Radi R. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11631–11638. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009429200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koppenol WH, Kissner R. Chem Res Toxicol. 1998;11:87–90. doi: 10.1021/tx970200x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bourassa JL, Ives EP, Marqueling AL, Shimanovich R, Groves JT. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:5142–5143. doi: 10.1021/ja015621m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ahmad S, Gromiha M, Fawareh H, Sarai A. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5 doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Su J, Groves JT. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:12979–12988. doi: 10.1021/ja902473r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Su J, Groves JT. Inorg Chem. 2010;49:6317–6329. doi: 10.1021/ic902157z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Myers B, Glazer AN. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:412–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee JB, Hunt JA, Groves JT. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:7493–7501. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Szabo C, Mabley JG, Moeller SM, Shimanovich R, Pacher P, Virag L, Soriano FG, Van Duzer JH, Williams W, Salzman AL, Groves JT. Mol Med. 2002;8:571–580. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shimanovich R, Hannah S, Lynch V, Gerasimchuk N, Mody TD, Magda D, Sessler J, Groves JT. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:3613–3614. doi: 10.1021/ja005856i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee JB, Hunt JA, Groves JT. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:6053–6061. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Koppenol WH, Moreno JJ, Pryor WA, Ischiropoulos H, Beckman JS. Chem Res Toxicol. 1992;5:834–842. doi: 10.1021/tx00030a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vance CK, Miller AF. Biochemistry. 2001;40:13079–13087. doi: 10.1021/bi0113317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stroupe M, DiDonato M, Tainer JA. In: Hanbook of Metalloproteins. Messerschmidt A, editor. Wiley; New York: 2001. pp. 941–951. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lymar SV, Hurst JK. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:8867–8868. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pryor WA, Lemercier JN, Zhang HW, Uppu RM, Squadrito GL. Free Radical Biol Med. 1997;23:331–338. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang HW, Squadrito GL, Pryor WA. Nitric oxide-Biology and Chemistry. 1997;1:301–307. doi: 10.1006/niox.1997.0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Goldstein S, Czapski G. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:3458–3463. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Augusto O, Bonini MG, Amanso AM, Linares E, Santos CCX, De Menezes SL. Free Radical Biol Med. 2002;32:841–859. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00786-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang H, Joseph J, Felix C, Kalyanaraman B. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:14038–14045. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.19.14038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen SN, Hoffman MZ. Radiat Res. 1973;56:40–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Medinas DB, Gozzo FC, Santos LFA, Iglesias AH, Augusto O. Free Radical Biol Med. 2010;49:1046–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yamakura F, Matsumoto T, Ikeda K, Taka H, Fujimura T, Murayama K, Watanabe E, Tamaki M, Imai T, Takamori K. J Biochem (Tokyo, Jpn) 2005;138:57–69. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvi095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Medinas DB, Augusto O. Free Radical Biol Med. 2010;49:682–682. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liochev SI, Fridovich I. Free Radical Biol Med. 2010;48:1565–1569. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Medinas DB, Cerchiaro G, Trindade DF, Augusto O. IUBMB Life. 2007;59:255–262. doi: 10.1080/15216540701230511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Elam JS, Malek K, Rodriguez JA, Doucette PA, Taylor AB, Hayward LJ, Cabelli DE, Valentine JS, Hart PJ. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:21032–21039. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300484200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Edwards RA, Whittaker MM, Whittaker JW, Baker EN, Jameson GB. Biochemistry. 2001;40:4622–4632. doi: 10.1021/bi002403h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sines J, Allison S, Wierzbicki A, Mccammon JA. J Phys Chem. 1990;94:959–961. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Getzoff ED, Cabelli DE, Fisher CL, Parge HE, Viezzoli MS, Banci L, Hallewell RA. Nature. 1992;358:347–351. doi: 10.1038/358347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bonini MG, Augusto O. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:9749–9754. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008456200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lahaye DE. Princeton University; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tabares LC, Cortez N, Hiraoka BY, Yamakura F, Un S. Biochemistry. 2006;45:1919–1929. doi: 10.1021/bi051947m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tabares LC, Cortez N, Un S. Biochemistry. 2007;46:9320–9327. doi: 10.1021/bi700438j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vathyam S, Byrd RA, Miller AF. Magn Reson Chem. 2000;38:536–542. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Padmaja S, Au V, Madison SA. J Chem Soc, Dalton Trans. 1999:2933–2938. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Xu SQ, Ying J, Jiang BB, Guo W, Adachi T, Sharov V, Lazar H, Menzoian J, Knyushko TV, Bigelow D, Schoneich C, Cohen RA. American Journal of Physiology Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2006;290:H2220–H2227. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01293.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Neumann H, Hazen JL, Weinstein J, Mehl RA, Chin JW. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:4028–4033. doi: 10.1021/ja710100d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Quint P, Reutzel R, Mikulski R, McKenna R, Silverman DN. Free Radical Biol Med. 2006;40:453–458. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Martinez-Ruiz A, Lamas S. IUBMB Life. 2009;61:91–98. doi: 10.1002/iub.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hopper RK, Carroll S, Aponte AM, Johnson DT, French S, Shen RF, Witzmann FA, Harris RA, Balaban RS. Biochemistry. 2006;45:2524–2536. doi: 10.1021/bi052475e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Saha A, Goldstein S, Cabelli D, Czapski G. Free Radical Biol Med. 1998;24:653–659. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00365-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Uppu RM, Squadrito GL, Cueto R, Pryor WA. Nitric Oxide, Pt B. 1996;269:285–295. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)69029-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Koppenol WH, Kissner R, Beckman JS. Nitric Oxide, Pt B. 1996;269:296–302. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)69030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Touati D. J Bacteriol. 1983;155:1078–1087. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.3.1078-1087.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gao BF, Flores SC, Bose SK, McCord JM. Gene. 1996;176:269–272. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00246-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Vance CK, Miller A-F. Biochemistry. 1998;37:5518–5527. doi: 10.1021/bi972580r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Beyer WF, Reynolds JA, Fridovich I. Biochemistry. 1989;28:4403–4409. doi: 10.1021/bi00436a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Harned HS, Bonner FT. J Am Chem Soc. 1945;67:1026–1031. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Radi R, Denicola A, Freeman BA. Methods Enzymol. 1999;301:353–367. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)01099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.