Abstract

Group IVA cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2α) catalyzes the first step in the arachidonic acid cascade leading to the synthesis of important lipid mediators, the prostaglandins and leukotrienes. We previously described a patient deficient in cPLA2α activity, which was associated with mutations in both alleles coding for the enzyme. In this paper we describe the biochemical characterization of each of these mutations. Using saturating concentrations of calcium we showed that the R485H mutant was nearly devoid of any catalytic activity, that the S111P mutation did not affect the enzyme activity and that the known polymorphism K651R was associated with slightly higher activity than wild type. Using MDCK cells, we showed that translocation to the Golgi in response to serum activation was impaired for the S111P mutant but not for the other mutants. Using immortalized mouse lung fibroblasts lacking endogenous cPLA2α activity, we showed that both mutations S111P and R485H/K651R caused a profound defect in the enzyme catalytic activity in response to cell stimulation with serum. Taken together, our results show that the mutation S111P hampers calcium binding and membrane translocation without affecting the catalytic activity, and that the mutation R485H does not affect membrane translocation but blocks catalytic activity leads to inactivation of the enzyme. Interestingly, our results show that the common polymorphism K651R confers slightly higher activity to the enzyme suggesting a role of this residue in favoring a catalytically active conformation of cPLA2α. Our results define how the mutations negatively influence cPLA2α function and explain the inability of the proband to release arachidonic acid for eicosanoid production.

Group IVA cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2α) is a widely expressed enzyme in mammalian cells that catalyzes the hydrolysis of phospholipids in the sn-2 position to release arachidonic acid (AA). It is stimulated in response to diverse factors and represents the first step of metabolic cascades leading to generation of important lipid mediators such as prostaglandins and leukotrienes. These eicosanoids mediate physiological and pathophysiological processes, making it important to understand the factors regulating cPLA2α activity. Two knock-out mouse models provided important information concerning the physiological function of cPLA2α (1–3).

Recently we described a patient with globally decreased eicosanoid production, intestinal ulcers, and platelet dysfunction (4). We showed that these conditions were associated with loss-of-function mutations in both alleles coding for cPLA2α. Release of thromboxane (TxA2) and 12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (12-HETE) by the patient’s platelets was reduced by more than 95% compared to control individuals, suggesting that cPLA2α is the main phospholipase responsible for platelet release of eicosanoids.

Sequencing of cDNA revealed that the patient was a compound heterozygote for variants in the PLA2G4A gene. An allelic variant, S111P, was inherited from his mother, and the paternal allele contained the variant R485H as well as the known K651R single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP). In this manuscript, we describe the biochemical characterization of these mutations.

cPLA2α has two functional domains: an N-terminal C2 domain that binds calcium and a C-terminal catalytic domain (5, 6). Calcium binding to the C2 domain initiates translocation of the enzyme from the cytosol to the membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum, the Golgi and the nuclear envelope for cPLA2α to access phospholipid substrate (3). The cPLA2α C2 domain is an anti-parallel β-sandwich composed of two, four stranded sheets with interconnecting loops (7, 8). Two calcium ions bind to residues in calcium-binding loops (CBL) 1–3 at the membrane-binding end of the C2 domain. The variant S111P is located as the first amino acid in the loop at the opposite end of the β-strand from CBL3, a region that provides the basis for a hypothesis that this allelic variant alters the calcium binding function of the C2 domain. The catalytic domain contains a large, positively charged region that is present in the membrane-facing region of cPLA2α (9), and the patient’s R485H variant is located in this region. The residue R485 is in proximity to the cluster of lysine residues (K488/K541/K543/K544) that is the site of interaction with phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PI-(4,5)-P2), which increases catalytic activity in vitro (10–12).

This patch of basic residues is required for cPLA2α-mediated AA release in cells but does not regulate calcium-dependent translocation in cells or membrane binding in vitro (10, 12). We hypothesized that the R485H variant could result in altered catalytic activity. The K651R variant is a recognized SNP located in the C-terminal region of the catalytic domain. Although there is no information about this region that engenders a specific functional hypothesis, K651 is a highly conserved residue across species, suggesting the possibility of a functional consequence of this variant.

In order to better understand the effect of each mutation on cPLA2α function, we compared their interfacial binding and activity in vitro using purified enzymes, and their ability to translocate to membrane and release AA in response to calcium increases when expressed in mammalian cells.

Materials and Methods

Materials

[5,6,8,9,11,12,14,15-3H]AA (100 Ci/mmol) was from Amersham Biosciences. 1-Palmitoyl-2[14C]-arachidonyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (14C-PAPC) was from PerkinElmer Life Sciences. Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) was from BioWhittaker. Penicillin, streptomycin and L-glutamine were from Invitrogen. Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was from Irvine Scientific. Protease inhibitor tablets were from Roche Applied Science. The plasmid isolation kit was from Qiagen, and the Quik II Site Directed Mutagenesis kit was from Stratagene. Mouse serum was from Atlanta Biologicals. Sodium phosphate, potassium phosphate, sodium chloride, ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid, imidazole, hepes, dithiothreitol, Tris-HCl and bovine serum albumin (BSA) were purchased from Sigma. Vectors pCR 2.1 and pcDNA 3 were from Invitrogen as were the Nu-PAGE 10% Bis-Tris gels and the Ni-NTA agarose. Restriction enzymes and T4 DNA ligase were from New England Biolabs. The Qiagen kit for PCR was from Qiagen. Baculovirus vector pAcHLT-B and the Baculogold Baculovirus Expression System were purchased from BD Biosciences. Glycerol was from Fisher Scientific. Slide-a-lyzer dialysis cassettes were from Pierce.

Preparation of a baculovirus vector for cPLA2α

The cDNA for the double mutant cPLA2α R485H/K651R was purified from the patient’s lymphoblasts (4) and cloned in pcDNA 3 according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This construct was used as a template for PCR cloning into the baculovirus transfer plasmid pAcHLT-B. The upper primer including the Xho restriction site and in frame with the baculovirus vector was: GCT CGA GAA ATG TCA TTT ATA GAT CCT TAC CAG CAC A. The lower primer containing the stop codon and the Kpn1 restriction site was: CGG TAC CCT ATG CTT TGG GTT TAC TTA GAA ACT CCT T. The PCR product was cut with Xho1 and Kpn1 restriction enzymes, purified with the Qiagen kit for PCR and ligated into pCR2.1 using T4 DNA ligase. The ligation was transformed into DH5-Alpha competent cells, utilizing blue-white screening, cultured, sequenced and purified for ligation into the purified baculovirus vector, pAcHLT-B. The construct was confirmed by sequencing. The mutants S111P, R485H, K651R and wild type were prepared by site-directed mutagenesis using the QuikChangeII kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. The mutations were confirmed by sequencing.

Expression and purification of cPLA2α

Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) insect cells were a generous gift from Dr. Lawrence Marnett at Vanderbilt. Cells were maintained in SF 900 II SFM medium in Erlenmeyer flasks at 27°C in a rotating incubator set at 150 rpm. Baculovirus vector pAcHLT-B containing each cPLA2α insert and the Baculogold linearized baculovirus DNA were co-transfected into Sf9 insect cells according to the Baculovirus Expression system protocol.

To amplify, insect cells were infected with recombinant baculovirus and purified according to a modification of the method of Gelb (13). Supernatant containing virus from each mutant and the wild type was used to infect Sf9 cells, which grew in culture for 68 h. After cells were harvested all steps were carried out at 4°C. Briefly, infected cells were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min. The pellet was resuspended in buffer composed of 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl and protease inhibitors, placed on ice and homogenized in a Potter dounce. After 20 min on ice, cell lysates were centrifuged for 45 min at 100,000×g.

Supernatant was loaded without dilution onto a Ni-NTA agarose column previously prepared by washing with the above Tris buffer containing 700 mM NaCl. The column was then washed with 50 mM NaH2PO4 pH 6.0, 750 mM NaCl and 20 mM imidazole, then with 20 mM imidazole in NaH2PO4, pH 8.0, followed by 100 mM imidazole in same. All wash and imidazole fractions were collected and electrophoresed on a 10% polyacrylamide gel to check for purity. Fractions containing cPLA2α were pooled and dialyzed against 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 1mM DTT and 10% glycerol in a cassette overnight at 4ºC.

Post dialysis material was electrophoresed on a 10% gel and stained with Coomassie Blue to determine purity. The protein concentration of affinity purified wild type and mutant cPLA2α preparations was determined by the Bradford dye-binding assay using BSA as a standard, and by measuring OD280 using 0.87 (mg/ml)-1 cm-1 (calculated from the amino acid sequence of cPLA2α), which gave comparable results.

Enzymatic activity and interfacial binding assays of cPLA2α mutants

Vesicle hydrolysis studies were carried out as described previously (12) using extruded vesicles of 14C-PAPC (2.7 Ci/mol) (200 μM phospholipid) and 200 ng enzyme (based on Bradford assay) in 10 mM MOPS, pH 7.2, 0.5 mM EGTA, 100 mM KCl, 0.5 mg/ml fatty acid-free BSA and various amounts of CaCl2 (as a Ca2+ buffer) to give the indicated concentration of free Ca2+. Reactions were incubated at 37°C for 5 min and the amount of free fatty acid released determined as described (12). Values were corrected for the small amount of radioactive fatty acid in a reaction mixture that lacked enzyme.

Vesicle binding studies were carried out as described previously (12) using PAPC vesicles. In the case of cPLA2α-R485H we used 200 ng of enzyme instead of 50 ng since the activity of this mutant is low. Also for this mutant we estimated the amount of enzyme remaining in the supernatant by western blot analysis. In this case 0.3 ml of supernatant above the pelleted vesicles was mixed with 1 ml of cold acetone and left at 4°C for 1 h. The sample was centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, the supernatant was removed, and the pellet was treated with Laemmli sample buffer and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The western blot was probed with anti-cPLA2α antiserum (Santa Cruz Cat. sc-438), and the blot was visualized with ECL.

Production of cDNA constructs and recombinant adenovirus

DNAs encoding monomeric (A206K) wild type enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP)- and enhanced cyan fluorescent protein (ECFP)-cPLA2α were inserted into the pVQAd5CMVK-NpA shuttle plasmid (Viraquest, Inc). The EYFP-cPLA2α construct was used to generate by site-directed mutagenesis the following mutants: S111P, R485H, K651R and R485H/K651R. Constructs were confirmed by sequencing. Adenoviruses were generated by ViraQuest Inc.

Cell culture and AA release assay

MDCK cells were cultured as previously described (14). Mouse lung fibroblasts (MLF) were isolated from wild type (MLF+/+) and cPLA2α knockout (MLF−/−) mice, and SV40 immortalized MLF (IMLF) were generated as previously described (15). IMLF−/− were plated at 1.25 × 104 cells/cm2 in 250 μl DMEM containing 10% FBS, 0.1% nonessential amino acids, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 0.29 mg/ml glutamine (growth media) in 48 well plates. After 18 h in 5% CO2 at 37°C, cells were washed with, and incubated in, serum-free and antibiotic-free DMEM containing 0.1% BSA (stimulation media). Cells were infected with adenoviruses in 100 μl/well. After 1.5 h, 150 μl of stimulation media containing 0.2 μCi/ml [3H]AA was added to each well. After 26 h, cells were washed twice and fresh stimulation media was added. Culture media was collected after stimulation, centrifuged for 10 min at 15,000 RPM, and radioactivity was determined by scintillation counting. Cells were scraped into 50 μl of 0.1% Triton X-100 containing protease inhibitors, and the lysates were used to determine the total cellular radioactivity and to determine expression levels of wild type and mutant cPLA2α via immunoblotting as previously described (12). The amount of AA release into the culture media was calculated as a percentage of the total radioactivity (cells plus media) in each well.

Microscopy

MDCK cells and IMLF−/− were plated at 1.25 × 104 cells/cm2 in 250 μl growth media in glass-bottomed MatTek plates, and infected with adenoviruses for expression of wild type and mutant cPLA2α as described above. Microscopy was conducted on an inverted Zeiss 200M microscope driven by Intelligent Imaging Innovations Inc. (3I) software (Slidebook 4.1). Fluorescence data were calculated after subtracting background fluorescence, and correcting for differential bleaching at each wavelength.

Immunoblotting

For western blotting, cell lysates were prepared in ice cold buffer containing 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 150 mM sodium chloride, 1.5 mM magnesium chloride, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EGTA and protease inhibitors. Lysates were centrifuged at 15,000 g for 10 min at 4°C and protein concentration was determined using the bicinchoninic acid reagent. Lysates were diluted in Laemmli buffer and boiled for 5 min at 100°C. Proteins were separated on 10% SDS polyacrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose, and blocked for 1 h in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.25% Tween 20 and 5% nonfat dry milk. Nitrocellulose membranes were incubated overnight with a 1:5,000 dilution of anti-cPLA2α antibodies diluted in blocking buffer. Immunoreactive protein was detected using the Amersham Biosciences anti-rabbit secondary antibody and ECL system.

Results

Effect of the mutations on cPLA2α catalytic activity and interfacial binding

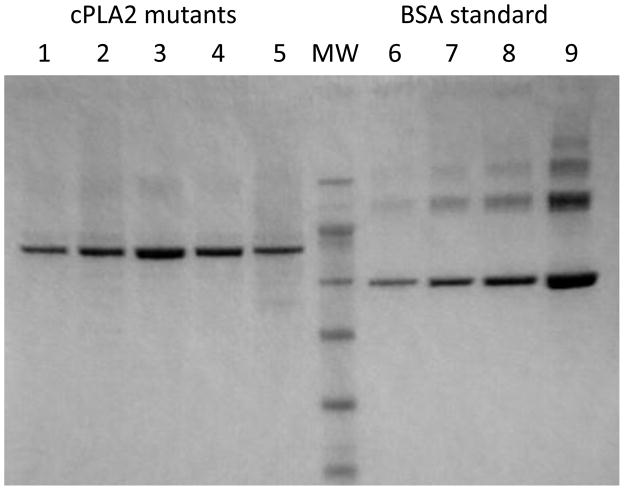

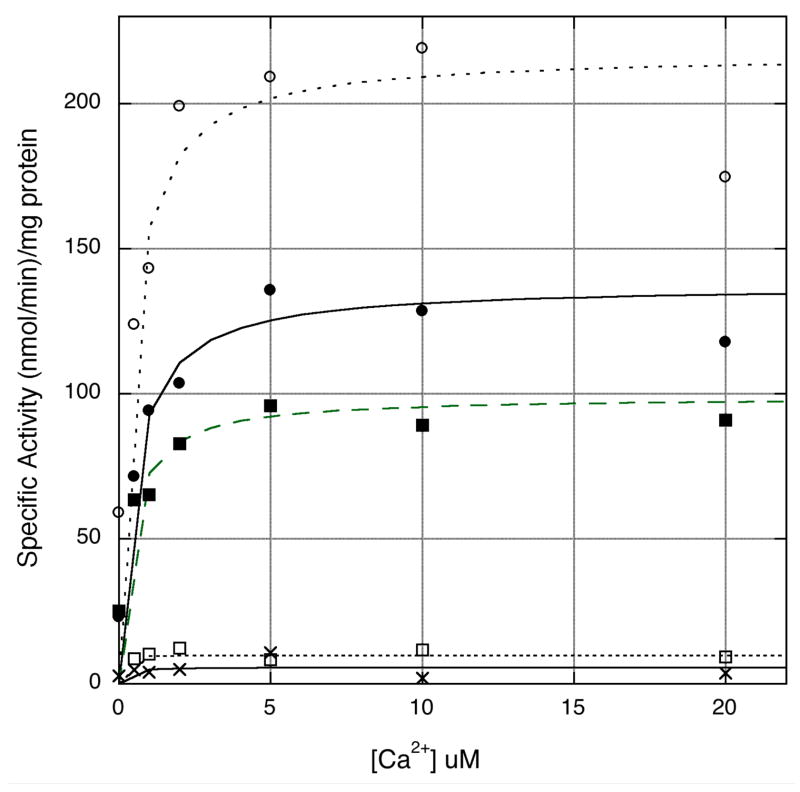

To study the effect of the mutations on cPLA2α catalytic activity and vesicle binding, affinity purified His-tagged wild type and cPLA2α mutants expressed in Sf9 cells were used. Assessment of the purity by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1) showed that all preparations were more than 90% pure. When assayed at saturating concentration of Ca2+, the S111P mutant had slightly decreased catalytic activity compared to wild type cPLA2α (Table 1, Fig. 2). The single R485H and double R485H/K651R mutants were nearly devoid of catalytic activity (Table 1, Fig. 2). The K651R mutant exhibited 1.7-fold higher activity than wild-type cPLA2α indicating that the R485H mutation is the determinant of the overall effect of the double mutation on the enzyme activity. A comparison of the enzymatic properties of wild type and the cPLA2α mutants assayed as a function of calcium concentration revealed that the apparent KCa (concentration of Ca2+ that supports half maximal activity obtained at saturating Ca2+) of the K651R and S111P mutants (0.4 μM) is similar to wild type cPLA2α (0.5 μM) (Fig. 2, Table 1).

Figure 1. SDS-PAGE of purified mutants of cPLA2α.

cPLA2α mutants were expressed and purified as described in Materials and Methods. 1 μl of each purified mutant was loaded on a SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue. A standard curve of bovine serum albumin (BSA) was loaded on the same gel (lanes 6 to 9) at the following concentrations (0.3; 60.; 1.25; 2.5 μg/ml). Lanes 1 to 5 correspond to wild type, R485H, R485H/K651R, K651R and S111P, respectively. MW: molecular weight markers.

Table 1.

In vitro analysis of wild type and cPLA2α mutant proteins. Each value is the average of duplicate determinations.

| protein | Specific activity at saturating [Ca2+] (nmol/min)/mg protein | Apparent KCa (μM) | Fraction enzyme bound to vesicles at 20 μM Ca2+ |

|---|---|---|---|

| cPLA2α-wild type | 140 | 0.5 +/− 0.2 | 0.85 |

| cPLA2α-R485H | 7 | 0.70 | |

| cPLA2α-K651R | 233 | 0.4 +/− 0.2 | |

| cPLA2α-R485H/K651R | 7 | ||

| cPLA2α-S111P | 109 | 0.4 +/− 0.2 | 0.58 |

Figure 2. Specific activities of wild type cPLA2α and mutants as a function of calcium concentration.

Hydrolysis of [14C]PAPC vesicles by affinity purified wild type cPLA2α (●) and S111P (■), K651R (○), R485H (✕) and K651R/R485H (□) mutants was measured as described in Materials and Methods.

When interfacial binding of wild type cPLA2α and the mutants to PAPC vesicles at saturating calcium (20 μM) was assayed, the results show that a lower fraction (about 68%) of the S111P mutant is bound than wild type (Table 1). Since the catalytic activity of the S111P mutant is about 73% of wild type at saturating calcium (Table 1), the results suggests that the S111P mutation affects calcium-dependent binding and not catalytic activity. The R485H mutant binds vesicles at saturating calcium to a similar extent as wild type cPLA2α indicating that the lack of enzymatic activity of the R485H mutant is due to a modification of the catalytic domain rather than an affect on calcium-dependent binding through the C2 domain (Table 1).

Effect of the mutations on cPLA2α translocation in cells

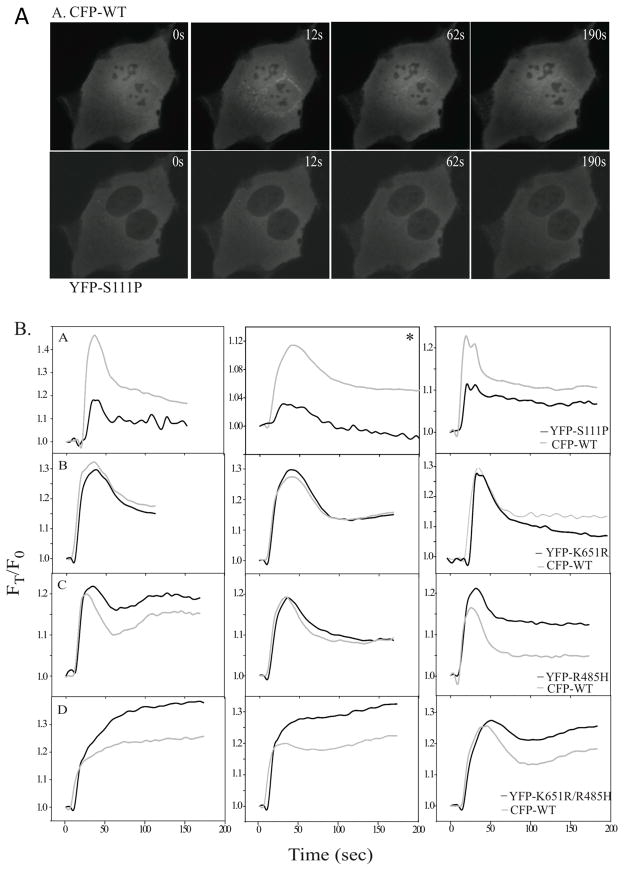

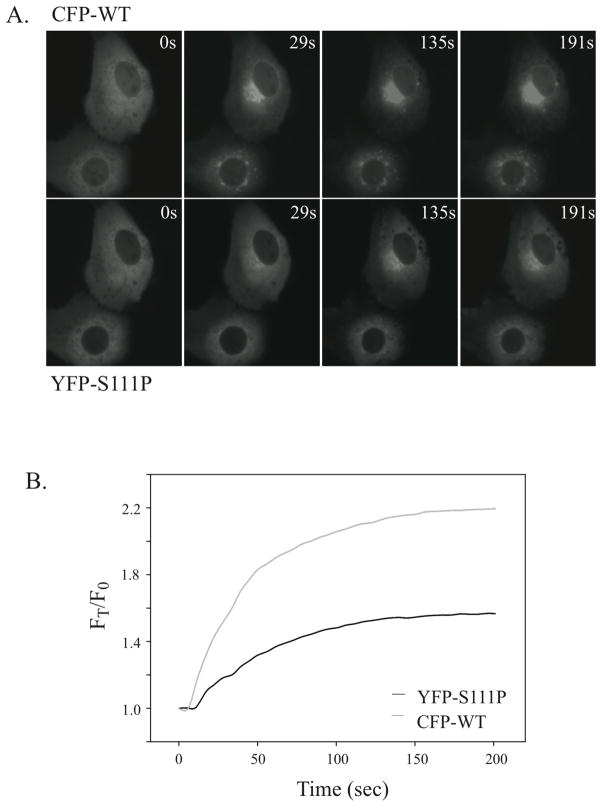

We had previously defined the intracellular calcium signals regulating cPLA2α translocation to Golgi in MDCK cells (14). This cell model was used initially to determine the effect of the mutations on the ability of cPLA2α to translocate to Golgi in response to increases in [Ca2+]i. Wild type ECFP-cPLA2α was co-expressed with either EYFP-cPLA2a-S111P, EYFP-cPLA2a-R485H or EYFP-cPLA2α-K651R/R485H, which allows a direct comparison of the translocation properties of wild type and mutant enzymes in the same cell (12, 14). Translocation was monitored by dual live-cell imaging in response to 1 μM ionomycin, which induces a calcium transient that correlates in a time-dependent manner with ECFP-cPLA2α translocation to Golgi in MDCK cells (14). Translocation of wild type ECFP-cPLA2α to the perinuclear region occurs rapidly as shown in the images of cellular fluorescence (Fig. 3A). In contrast, there is less translocation of EYFP-cPLA2α-S111P than wild type ECFP-cPLA2α when expressed in the same cell (Fig. 3A). Analysis of several individual cells revealed less translocation of cPLA2α with the C2 domain mutation (S111P) than wild type cPLA2α depicted graphically for 3 individual cells in Fig. 3B (panels A). The EYFP-cPLA2α-S111P mutant translocates at a slighty slower rate in response to calcium increase, and a lower fraction of the mutant translocates to membrane compared to wild type. cPLA2α containing the SNP allele K651R shows identical translocation properties as wild type cPLA2α (Fig. 3B, panels B). Translocation of cPLA2α containing the single R485H or double R485H/K651R mutant alleles in the catalytic domain is also similar to wild type cPLA2α (Fig. 3B, panels C & D). We also compared translocation of wild type ECFP-cPLA2α and the EYFP-cPLA2α-S111P mutant in response to a higher concentration of ionomycin, which induces a higher and more sustained increase in [Ca2+]i in MDCK cells (14). There is greater translocation of EYFP-cPLA2α-S111P to the Golgi than with lower levels of ionomycin, but it still remains below the level of translocation observed with wild type ECFP-cPLA2α as seen in the images (Fig. 4A) and depicted graphically (Fig. 4B).

Figure 3. Translocation of wild type cPLA2α and mutants in MDCK cells stimulated with 1 μM ionomycin.

A. Images of a representative cell co-expressing wild type ECFP-cPLA2α (top panels) and EYFP-cPLA2α-S111P (bottom panels) are shown at the indicated times after adding 1 μM ionomycin. B. MDCK cells co-expressing wild type ECFP-cPLA2α and either EYFP-cPLA2α-S111P (panels A), EYFP-cPLA2α-K651R (panels B), EYFP-cPLA2α-R485H (panels C) or EYFP-cPLA2α-K651R/R485H (panels D) were stimulated with 1 μM ionomycin and images were collected every 3 sec as a function of time as indicated. The three graphs shown side-by-side in Panels A–D depict translocation data for three individual cells. Translocation data of individual cells shown graphically in each panel were calculated based on average fluorescence intensity of a mask of the Golgi in each cell. Values are corrected for background fluorescence and differential bleaching at each wavelength throughout the duration of the imaging. Data are presented relative to time 0 (FT/F0).

Figure 4. Translocation of wild type cPLA2α and cPLA2α-S111P mutant in MDCK cells at saturating calcium.

MDCK cells co-expressing wild type ECFP-cPLA2α and EYFP-cPLA2α-S111P were stimulated with 10 μM ionomycin and images were collected as a function of time as indicated. A. Images of a representative cell co-expressing wild type ECFP-cPLA2α (top panels) and EYFP-cPLA2α-S111P (bottom panels) are shown at the indicated times after adding 10 μM ionomycin. B. Ionomycin (10 μM)-stimulated translocation is shown graphically in a representative MDCK cell co-expressing wild type ECFP-cPLA2α and EYFP-cPLA2α-S111P. Live cell imaging is carried out as described in Fig. 3 legend.

Effect of the mutations on cPLA2α translocation and AA release when reconstituted in cPLA2α-deficient lung fibroblasts

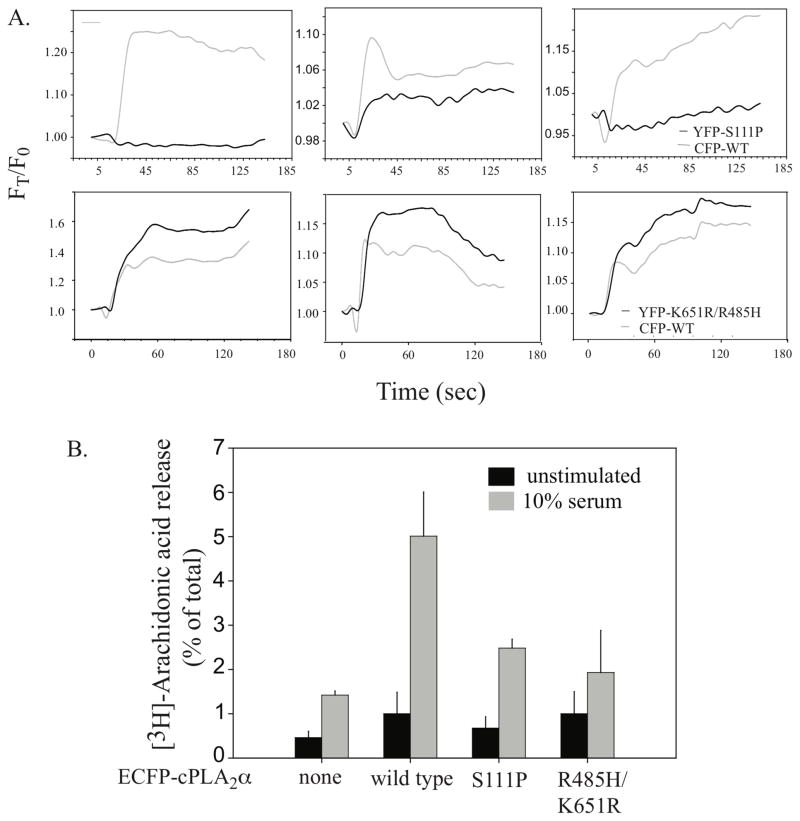

In order to directly compare the translocation properties and the ability of the cPLA2α mutants to release AA, they were expressed in IMLF−/−, a cell type that lacks endogenous cPLA2α. We previously reported that expression of wild type cPLA2α in IMLF−/− reconstitutes AA release and allows evaluation of cPLA2α function without interference of endogenous cPLA2α (12). In addition we can use the physiological agonist serum to stimulate these cells. When expressed in IMLF−/−, cPLA2α is potently activated by serum, which induces a capacitative increase in [Ca2+]i and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (12). Serum stimulates less translocation of EYFP-cPLA2α-S111P than wild type cPLA2α when co-expressed in IMLF−/−, as observed in MDCK cells (Fig. 5A, top three panels). The extent of translocation of the S111P mutant relative to wild cPLA2α is variable from cell-to-cell. In some cells translocation of S111P is undetectable and in others a low level of translocation to Golgi is observed. In contrast, the EYFP-cPLA2α-R485H/K651R mutant actually translocates to a greater extent than the wild type in response to serum (Fig. 5A, lower three panels).

Figure 5. Translocation of wild type cPLA2α and mutants in IMLF−/− stimulated with serum.

A. Translocation is shown in 3 individual IMLF−/− co-expressing wild type ECFP-cPLA2α with EYFP-cPLA2α-S111P (top three panels) or with EYFP-cPLA2α-K651R/R485H (bottom three panels) as a function of time after stimulation with 10% serum. Live cell imaging is carried out as described in Fig. 4 legend. B. Parallel cultures of [3H]AA-labeled IMLF−/− expressing either wild type ECFP-cPLA2α, EYFP-cPLA2α-S111P, EYFP-cPLA2α-K651R/R485H or no cPLA2α (none) as indicated were stimulated for 10 min with 10% serum. [3H]AA released into the medium is expressed as a percentage of the total cellular radioactivity in each well. Immunoblotting of cell lysates was conducted to confirm equivalent levels of expression of wild type and mutant cPLA2α in each well.

To determine the effect of the mutations on AA release, parallel cultures of IMLF−/− expressing wild type or mutant forms of cPLA2α were compared (Fig. 5B). For each experiment, western blot analysis of the cell lysates was carried out to confirm that wild type and mutant forms of cPLA2α are expressed at equivalent levels as previously described (12). The R485H/K651R mutant did not release significant amounts of AA above basal levels in response to serum indicating that although calcium-dependent translocation is not defective it is catalytically inactive. The release of AA by the S111P mutant is reduced by approximately 72% compared to wild type cPLA2α in response to serum (Fig. 5B). The low but significant level of AA released by the S111P mutant in response to serum suggests that it is catalytically active consistent with the in vitro activity assays.

Discussion

cPLA2α activity is regulated by complex mechanisms involving binding of intracellular calcium, posttranslational phosphorylation, and interaction with specific membrane lipids (3, 16, 17). Given the importance of cPLA2α in platelet function (4), and its ubiquitous expression in tissues, structure function studies are needed to shed light on the mechanisms regulating cPLA2α in humans. We recently described the first case of a patient devoid of cPLA2α activity due to mutations in both alleles coding for the enzyme (4). One allele codes for a non-homologous mutation, S111P. The other allele codes for two non-homologous mutations: R485H and K651R. In this paper, we investigated the functional consequences of these three mutations with regard to catalytic activity, Ca2+ requirement and affinity for phospholipid membrane in vitro and in cells in culture.

All mutants express well at the expected molecular weight, and none of the mutations have a significant impact on the recognition of the mutated enzymes by the cPLA2α specific antibody used for western blot analysis. We previously observed that although no cPLA2α activity was present in the proband’s platelets, about 50% of the protein was expressed. Taken together with our present results, this data suggest that, in contrast to insect cells, one of the mutations is associated with lower levels of protein expression in humans (4). The effects of the mutations on catalytic activity were assessed in vitro in the presence of saturating concentrations of calcium to remove any confounders due to different calcium requirements of each mutant. S111P has no significant effect on the mutant’s catalytic activity as measured by hydrolysis of AA from phospholipid vesicles, suggesting that the integrity of the catalytic active site is not affected by this mutation. The mutant R485H is nearly completely devoid of activity indicating that R485 is important for the catalytic activity of cPLA2α. This amino acid is in the vicinity of the positively charged lid that covers the active site (4). Mutation of other basic residues (K483, K541, K543, K544), that constitute the site for activation by PI(4,5)P2, to asparagines slightly enhances activity against PAPC but abolishes activation by PI(4,5)P2 (11, 18, 19). In contrast, the substitution of R485 with a histidine results in inactivation perhaps by an adverse conformation effect. The mutation K651R confers slightly increased activity of cPLA2α when compared to wild type. This observation was unexpected as the residue is in the cytosolic C-terminal loop and not obviously associated with the catalytic active site of the enzyme. We can hypothesize that this residue might be involved in the overall interaction of the enzyme with the phospholipids or have a stabilizing effect on the catalytic domain through three-dimensional interactions or by stabilizing the active conformation of cPLA2α. Interestingly, this mutation is a previously described polymorphism of the enzyme (rs2307198) with an allele frequency of 2 to 6 % according to the population studied (ensembl.org). Our results raise the question as to whether this polymorphism is associated with increased cPLA2α activity in humans.

A rise in intracellular Ca2+ concentration is essential in promoting translocation of cPLA2α to the membrane where it can catalyze release of AA from phospholipids. We investigated the effects of the different mutations on calcium-dependent binding to phospholipid vesicles in vitro. Our results show that S111P binding at saturating Ca2+ concentration does not reach maximal level of association exhibited by wild type enzyme. The loss of a H-bonding interaction due to substitution of a proline for S111 could potentially affect the conformation of the β strands 6 and 7 due to unfavorable steric effects. This could affect the conformation of CBL-3, which is connected to B6 strand, resulting in effects on calcium-dependent membrane association. In contrast, the R485H mutant exhibits similar association to vesicles as wild type at saturating calcium.

We investigated the effects of the mutations on cPLA2α translocation to membranes by monitoring the association of the different mutants to the Golgi in MDCK cells stimulated with ionomycin since we had extensively characterized the calcium-dependent translocation properties of wild type cPLA2α in this cell model (14, 20). At 1 μM ionomycin a lower fraction of the cellular S111P mutant expressed in MDCK cells translocates to the Golgi compared to wild type. However, when the calcium transient is more sustained with higher levels of ionomycin (14), more wild type and S111P mutant accumulate on the Golgi over-time than with lower ionomycin but there is still less S111P mutant cPLA2α associated with Golgi than wild type consistent with our in vitro data. A defect in translocation of the S111P mutant is also observed when it is co-expressed with wild type cPLA2α in IMLF−/− in response to serum. As we previously reported, serum is a physiological agonist that induces a typical capacitative calcium increase (12). Although there is cell-to-cell variability that may be due to heterogeneity in the calcium responses (21), translocation of the S111P mutant is lower than wild type. The defect in translocation results in less AA release by the S111P mutant when it is expressed at equivalent levels as wild type cPLA2α in IMLF−/− treated with serum (~70% less) for 60 min.

The R485H mutation causes a profound defect in cPLA2α catalytic activity. It has no catalytic activity measured as a function of calcium concentration in vitro, and does not release AA above control levels from IMLF−/− in response to calcium increases induced by serum. The R485H mutant translocates to Golgi at a similar rate as wild type cPLA2α suggesting that it responds similarly as wild type cPLA2α to calcium increases in cells. The R485H mutant has a tendency to accumulate to a greater extent on Golgi than wild type cPLA2α. This also occurs with cPLA2α mutations in the basic residues of the PI(4,5)P2 binding site, although the basis for this enhanced accumulation on the Golgi is not known. The substitution of R485 with a histidine is predicted to disrupt hydrogen-bonding interactions and create a destabilizing cavity (4).

Our results showing that S111P has catalytic activity when assayed in vitro and releases a low level of AA from cells contrasts with the in vivo data showing that cPLA2α activity in our patient is inhibited by more than 95% compared to control individuals (4). One contributing factor is the observation that in the proband’s platelets, about 50% of the wild type levels of cPLA2α protein are expressed, suggesting that one of the mutations is associated with lower level of protein expression. Another possibility is a dominant negative effect by which simultaneous expression of both R485H/K651R and S111P leads to more robust inhibition of cPLA2α activity than expression of S111P alone. We can hypothesize that binding of the inactive R485H mutant to the membrane competes for binding of S111P, further inhibiting the phospholipase activity.

Conclusion

In this manuscript we have characterized the biochemical consequences of the three non synonymous mutations described in a patient devoid of cPLA2α activity. Our results show that the mutation S111P hampers calcium binding leading to decreased affinity for phospholipid membranes but does not diminish the mutant’s catalytic activity. The common polymorphism K651R increases the catalytic activity of the enzyme, suggesting a role of this residue in favoring a catalytically active conformation of the enzyme. Finally, the R485H mutant does not adversely affect translocation but completely inactivates the enzyme, suggesting that this positively charged residue regulates the catalytic function of cPLA2α. Our results explain how the presence of these mutations in the two alleles of the patient lead to loss of cPLA2 activity and describe roles for residues previously unstudied, S111, R485 and K651.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the NIH (GM15431, HL81009, HL61378, HL50040).

Abbreviations

- 14C-PAPC

1-palmitoyl-2[14C]-arachidonyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- 12-HETE

12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid

- AA

arachidonic acid

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CBL

calcium-binding loops

- cPLA2α

Group IVA cytosolic phospholipase A2

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- ECFP

enhanced cyan fluorescent protein

- EYFP

enhanced yellow fluorescent protein

- FBS

Fetal bovine serum

- IMLF

SV40 immortalized MLF

- MLF

Mouse lung fibroblasts

- MDCK

Madin-Darby Canine Kidney

- PI-(4,5)-P2

phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

- Sf9

Spodoptera frugiperda

- TxA2

thromboxane A2

Bibliography

- 1.Uozumi N, Kume K, Nagase T, Nakatani N, Ishii S, Tashiro F, Komagata Y, Maki K, Ikuta K, Ouchi Y, Miyazaki J, Shimizu T. Role of cytosolic phospholipase A2 in allergic response and parturition. Nature. 1997;390:618–622. doi: 10.1038/37622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonventre JV, Huang Z, Taheri MR, O’Leary E, Li E, Moskowitz MA, Sapirstein A. Reduced fertility and postischaemic brain injury in mice deficient in cytosolic phospholipase A2. Nature. 1997;390:622–625. doi: 10.1038/37635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghosh M, Tucker DE, Burchett SA, Leslie CC. Properties of the Group IV phospholipase A2 family. Prog Lipid Res. 2006;45:487–510. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adler DH, Cogan JD, Phillips JA, 3rd, Schnetz-Boutaud N, Milne GL, Iverson T, Stein JA, Brenner DA, Morrow JD, Boutaud O, Oates JA. Inherited human cPLA(2alpha) deficiency is associated with impaired eicosanoid biosynthesis, small intestinal ulceration, and platelet dysfunction. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2121–2131. doi: 10.1172/JCI30473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nalefski EA, Sultzman LA, Martin DM, Kriz RW, Towler PS, Knopf JL, Clark JD. Delineation of two functionally distinct domains of cytosolic phospholipase A2, a regulatory Ca(2+)-dependent lipid-binding domain and a Ca(2+)-independent catalytic domain. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:18239–18249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dessen A, Tang J, Schmidt H, Stahl M, Clark JD, Seehra J, Somers WS. Crystal structure of human cytosolic phospholipase A2 reveals a novel topology and catalytic mechanism. Cell. 1999;97:349–360. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80744-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perisic O, Fong S, Lynch DE, Bycroft M, Williams RL. Crystal structure of a calcium-phospholipid binding domain from cytosolic phospholipase A2. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1596–1604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perisic O, Paterson HF, Mosedale G, Lara-Gonzalez S, Williams RL. Mapping the phospholipid-binding surface and translocation determinants of the C2 domain from cytosolic phospholipase A2. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:14979–14987. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.21.14979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dessen A. Structure and mechanism of human cytosolic phospholipase A(2) Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1488:40–47. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Das S, Cho W. Roles of catalytic domain residues in interfacial binding and activation of group IV cytosolic phospholipase A2. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23838–23846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202322200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Six DA, Dennis EA. Essential Ca(2+)-independent role of the group IVA cytosolic phospholipase A(2) C2 domain for interfacial activity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:23842–23850. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301386200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tucker DE, Ghosh M, Ghomashchi F, Loper R, Suram S, John BS, Girotti M, Bollinger JG, Gelb MH, Leslie CC. Role of phosphorylation and basic residues in the catalytic domain of cytosolic phospholipase A2alpha in regulating interfacial kinetics and binding and cellular function. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:9596–9611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807299200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hixon MS, Ball A, Gelb MH. Calcium-dependent and -independent interfacial binding and catalysis of cytosolic group IV phospholipase A2. Biochemistry. 1998;37:8516–8526. doi: 10.1021/bi980416d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans JH, Spencer DM, Zweifach A, Leslie CC. Intracellular calcium signals regulating cytosolic phospholipase A2 translocation to internal membranes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:30150–30160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100943200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stewart A, Ghosh M, Spencer DM, Leslie CC. Enzymatic properties of human cytosolic phospholipase A(2)gamma. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29526–29536. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204856200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clark JD, Schievella AR, Nalefski EA, Lin LL. Cytosolic phospholipase A2. J Lipid Mediat Cell Signal. 1995;12:83–117. doi: 10.1016/0929-7855(95)00012-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leslie CC. Regulation of the specific release of arachidonic acid by cytosolic phospholipase A2. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2004;70:373–376. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leslie CC, Channon JY. Anionic phospholipids stimulate an arachidonoyl-hydrolyzing phospholipase A2 from macrophages and reduce the calcium requirement for activity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1045:261–270. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(90)90129-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mosior M, Six DA, Dennis EA. Group IV cytosolic phospholipase A2 binds with high affinity and specificity to phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate resulting in dramatic increases in activity. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2184–2191. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans JH, Leslie CC. The cytosolic phospholipase A2 catalytic domain modulates association and residence time at Golgi membranes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:6005–6016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311246200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williamson JR, Monck JR. Hormone effects on cellular Ca2+ fluxes. Annu Rev Physiol. 1989;51:107–124. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.51.030189.000543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]