Abstract

Purpose

Pathologic tooth migration (PTM) is a tooth displacement which is derived from imbalance of tooth retention force and is dominantly found out in maxillary anterior area. PTM in maxillary anterior area was tried to corrected with periodontal treatment and a clear aligner in this study and the result was evaluated clinically and radiographically.

Methods

For the treatment of a patient with chronic periodontal disease accompanied by maxillary anterior pathologic tooth migration, clear aligner was applied to move teeth after a series of case-related periodontal therapy. Clinically, probing depth, gingival recession, clinical attachment level and mobility were measured pre- and post-treatment, and radiographic examination was performed as well.

Results

Clinically, we found the decrease of the probing depth, gingival recession, clinical attachment level and mobility. And we could also acknowledge the reduction of vertical and horizontal dimension on infrabony defect radiographically. However, it is still controversial if there was an actual bone filling.

Conclusions

Clear aligner is an effective appliance to move teeth since it costs little in terms of expense and time. In addition, it wraps whole crowns, providing advantages to deal with crowding, spacing, and size of arch. In short, clear aligner could be a useful treatment option for PTM patient, since it provides decreased probing depth, gingival recession, clinical attachment level, mobility and esthetical restoration.

Keywords: Chronic periodontitis, Dental esthetics, Tooth migration

INTRODUCTION

Pathologic tooth migration (PTM) is tooth displacement resulting from the imbalance of tooth retention forces [1]. A variety of factors are regarded to be related to PTM, and the incidence is reported to be up to 50% of periodontitis patients [2,3]. The factors are, specifically, destruction of periodontium, inflammation in periodontal tissue, eruption force, oral habit, pressure in soft tissue, and occlusal force. Destruction of periodontium is one of the major causes of PTM, and it is known to make the incidence of PTM 3 to 8 times higher according to the amount of bone loss [2]. Inflammation in periodontal tissue increase hydrodynamic and hydrostatic forces around relevant vessels and tissues, possibly resulting in tooth displacement [4]. Eruption force may be a contributing factor, since extrusion is a common clinical feature of PTM [3]. Various occlusal factors are also related to PTM, as are oral habits such as lip and tongue habits, fingernail biting, thumb sucking, pipe smoking, and bruxism, and pressure from soft tissues like the tongue, cheek, and lips.

Treatment options for PTM are to remove causes and allow for natural healing, to provide limited additional orthodontic treatment after extraction of migrated teeth, and to generally straighten teeth [3]. Clear aligner, which is used for additional or limited orthodontic treatment of PTM, was introduced as a gingival stimulating appliance in 1926 [5], and Kesling [6] reported it to be used for tooth movement. Clear aligner is effective since it intermittently generates 3-dimensional orthodontic force. The protocol starts with applying a 0.5 mm-thick aligner for the first week. The thickness is then increased to 0.75 mm for the next 2 weeks. This procedure relieves patients' pain and decreases undesirable effects on the neighboring teeth with gradual teeth movement of 1 mm at each stage [7]. However, due to its elasticity and deformation, the appliance has to be remade every three weeks. Clear aligner might be indicated for a small amount (≤4 mm) of teeth movement, for instance, space closure, extrusion and intrusion, arch expansion and contraction, relapse of orthodontic treatment, and controlling the rotational axis of the teeth to remove crowding [8].

Ericsson et al. [9] noted that teeth movement without preorthodontic periodontal treatment could induce infrabony pockets since supra-gingival plaque goes under the gingiva along the movement. Wennström et al. [10] asserted that infrabony pockets would do no harm to clinical attachment if there was proper plaque control. Lindhe et al. [11] reported that orthodontic treatment after periodontal treatment can move teeth without attachment loss although it does not affect the clinical level itself in a positive way. Corrente et al. [12] wrote that an extruded tooth with an infrabony pocket showed decreased probing depth, clinical attachment gain, and bone filling radiographically after periodontal and orthodontic treatment. This study evaluates the effectiveness of periodontal treatment and a clear aligner for maxillary anterior PTM clinically and radiographically, based on the previous research mentioned above.

CASE DESCRIPTION

Subject

Three patients with chronic periodontitis and PTM who visited the Periodontal Department of the Chosun University Dental Hospital from May 2009 to July 2009 were sampled. Chronic periodontitis in the study is limited to cases accompanied by an infrabony pocket, tooth mobility ≤ 1°, and a sufficient amount of attached gingiva. Subjects for orthodontic treatment are defined as patients who have less than 4 mm PTM in the maxillary anterior area.

Clinical and radiographic examination

Clinical examination

The following clinical examinations were performed for the 3 patients pre- and post-periodontal and orthodontic treatment with a clear aligner.

Probing pocket depth

Clinical attachment gain

Gingival recession

Mobility

Radiographic examination

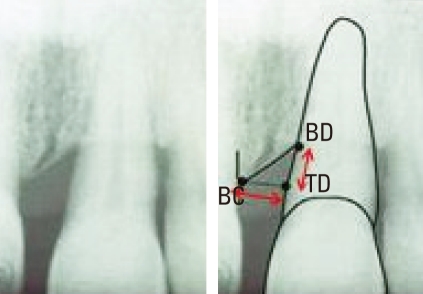

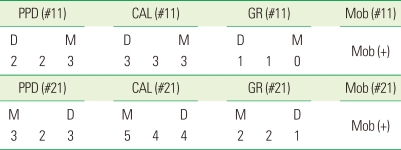

Subjects were checked to see if they had any infrabony pockets before periodontal treatment through panoramic and standard views. For the patients with an infrabony pocket, the vertical and horizontal size of the pocket was measured with the Infinitt π-ViewSTAR calipers at the Chosun University Dental Hospital Radiology System, as seen in Fig. 1. This method had been introduced by Corrente et al. previously (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Radiographic measurement. BC: horizontal distance from bone crest, BD: the most apical point of the bone defect, TD: vertical distance between the horizontal projection of the bone crest on the root surface, TD-BD: vertical dimension, BC-TD: horizontal dimension.

Treatment with clear aligner

After periodontal treatment, the clear aligner was applied. It was made on a patient's model cast, in which teeth were aligned after space analysis so that the patient's teeth would not be moved more than 1 mm by the appliance. Thermoplastic clear hard type (polyethylene) polymer was used with thicknesses of 0.5 mm and 0.75 mm. For the first week, a 0.5-mm-thick appliance was used, followed by a 0.75-mm-thick one for the subsequent two weeks. Patients were recalled every three weeks for new appliances. They were instructed to keep the appliance on all day long, with the exception of meal times.

Case reports

Case I

A 50-year-old male patient visited our department on July 14, 2009 with the chief complaint of anterior teeth sloping down and open. As mentioned above, clinical and radiographic examinations were performed (Tables 1 and 2, Fig. 2). He was diagnosed with chronic periodontitis localized in the maxillary anterior teeth area and pathologic tooth migration. The treatment plan was periodontal therapy to eliminate causes, tooth movement of 11, and prosthodontic treatment.

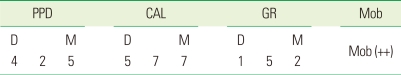

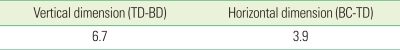

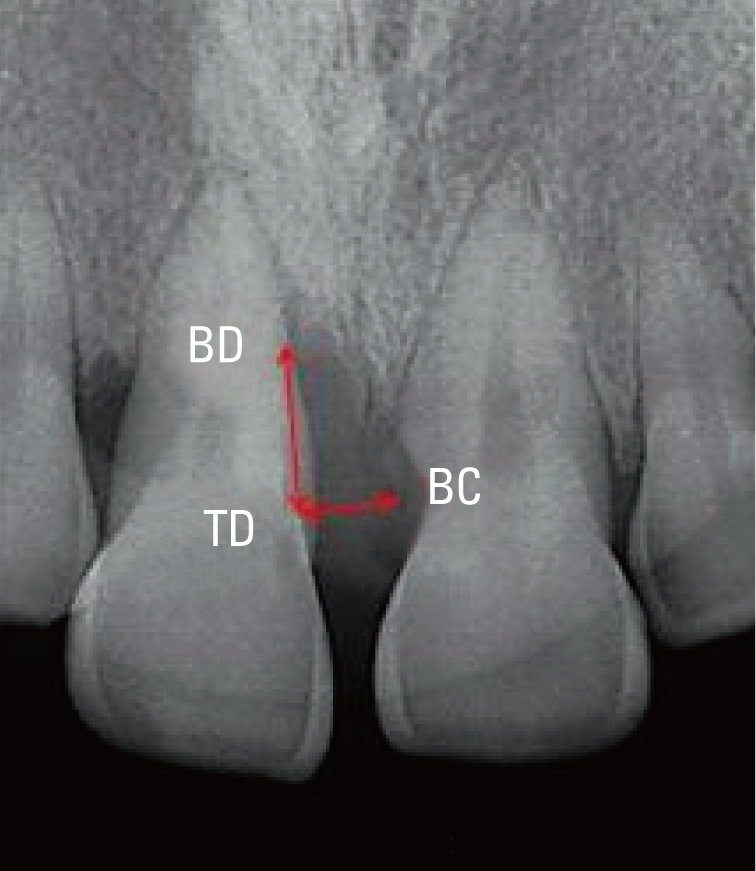

Table 1.

Clinical examination of #11 at first visit.

PPD: probing pocket depth, CAL: clinical attachment level, GR: gingival recession, Mob: mobility, D: distal, M: mesial.

Table 2.

Radiographic examination of #11 at first visit.

BC: horizontal distance from bone crest, BD: the most apical point of the bone defect, TD: vertical distance between the horizontal projection of the bone crest on the root surface, TD-BD: vertical dimension, BC-TD: horizontal dimension.

Figure 2.

Radiographic examination at first visit. BC: horizontal distance from bone crest, BD: the most apical point of the bone defect, TD: vertical distance between the horizontal projection of the bone crest on the root surface, TD-BD: vertical dimension, BC-TD: horizontal dimension.

Figs. 3 and 4 show clinical photographs of the front side and the occlusal plane after periodontal treatment. As mentioned above, teeth were fixed at the location to where the teeth would shift with wax on the cast after space analysis (Figs. 5 and 6), and the clear aligner was fabricated (Fig. 7).

Figure 3.

Pre-periodontal treatment (clinical photograph of the front view).

Figure 4.

Pre-periodontal treatment (clinical photograph of the occlusal plane view).

Figure 5.

Making the appliance (photograph of the cast from the front side).

Figure 6.

Making the appliance (photograph of the cast viewed from the occlusal plane).

Figure 7.

Clear aligner.

Figs. 8 and 9 show clinical photographs of the front side and the occlusal plane after 3 weeks. After space analysis, the teeth were fixed at the location where the teeth will be shifted to with wax again and the clear aligner was fabricated (Figs. 10 and 11).

Figure 8.

Three weeks after initial visit (clinical photograph of the front side).

Figure 9.

Three weeks after initial visit (clinical photograph of the occlusal plane).

Figure 10.

Appliance fabrication after 3 weeks (photograph of the cast from the front side).

Figure 11.

Appliance fabrication after 3 weeks (photograph of the cast from the occlusal plane).

Figs. 12 and 13 show photographs of the front side and occlusal plane after 6 weeks. Since the patient was satisfied with the results, use of a retention appliance was planned instead of prosthodontic treatment. After taking radiographs (Fig. 14), the retention appliance was applied (Fig. 15).

Figure 12.

Six weeks after initial visit (clinical photograph of the front side).

Figure 13.

Six weeks after initial visit (clinical photograph of the occlusal plane).

Figure 14.

Post-treatment. Radiography. BD: the most apical point of the bone defect, TD: vertical distance between the horizontal projection of the bone crest on the root surface, BC: horizontal distance from bone crest, TD-BD: vertical dimension, BC-TD: horizontal dimension.

Figure 15.

Retention.

As a result, the probing pocket depth (PPD) and gingival recession (GR) decreased about 1 mm, and clinical attachment level (CAL) decreased about 2 mm when compared to the first visit. Also, mobility decreased slightly (Table 3).

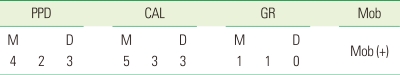

Table 3.

Post-treatment. Clinical examination of #11.

PPD: probing pocket depth, CAL: clinical attachment level, GR: gingival recession, Mob: mobility, D: distal, M: mesial.

In the radiographs, vertical and horizontal dimensions were measured (Table 4). Radiographically, the size of the infrabony defects decreased 0.8 mm vertically and 0.4 mm horizontally. However, actual bone filling in the lesions could not be determined based on the radiographic view alone.

Table 4.

Post-treatment. Radiographic measurements of #11.

BC: horizontal distance from bone crest, BD: the most apical point of the bone defect, TD: vertical distance between the horizontal projection of the bone crest on the root surface, TD-BD: vertical dimension, BC-TD: horizontal dimension.

Case II

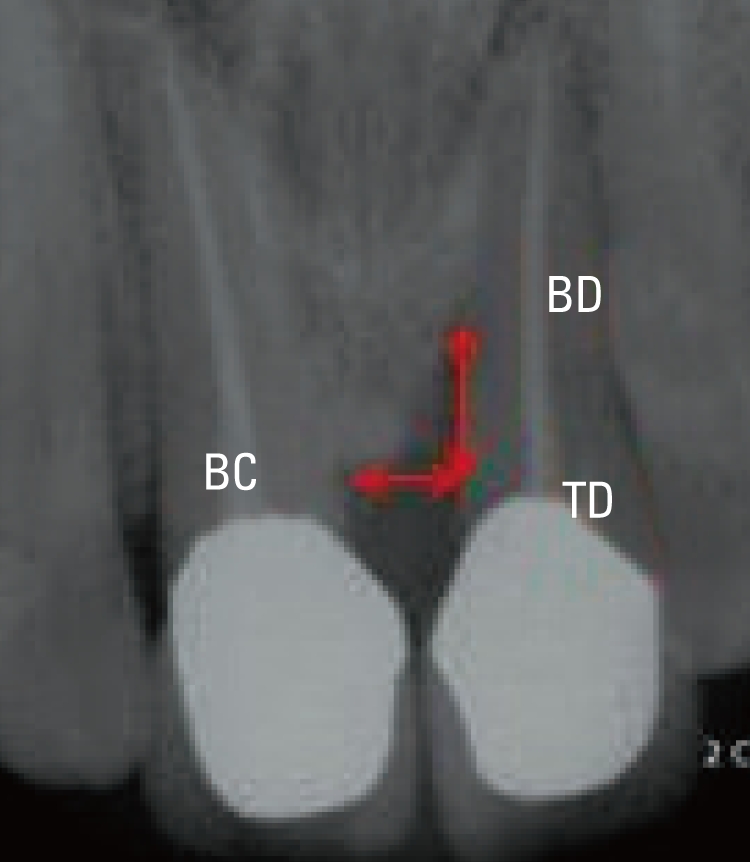

A 34-year-old male patient visited our department on May 25, 2009, with chief complaints of anterior teeth separating and discomfort in the gums. As described above, clinical and radiographic examinations were performed (Tables 5 and 6, Fig. 16). He was diagnosed with an endo-perio lesion due to loss of tooth vitality and the pathologic tooth migration of 21. The treatment plan was periodontal therapy to eliminate causes, tooth movement of 11 and 21, and prosthodontic treatment.

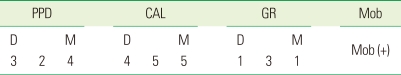

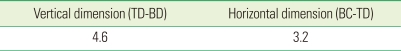

Table 5.

Clinical examination of #21 at first visit.

PPD: probing pocket depth, CAL: clinical attachment level, GR: gingival recession, Mob: Mobility, M: mesial, D: distal.

Table 6.

Clinical examination of #21 at first visit.

BC: horizontal distance from bone crest, BD: the most apical point of the bone defect, TD: vertical distance between the horizontal projection of the bone crest on the root surface, TD-BD: vertical dimension, BC-TD: horizontal dimension.

Figure 16.

Radiographic examination at first visit. BC: horizontal distance from bone crest, BD: the most apical point of the bone defect, TD: vertical distance between the horizontal projection of the bone crest on the root surface, TD-BD: vertical dimension, BC-TD: horizontal dimension.

Figs. 17 and 18 are clinical photographs of the front side and the occlusal plane after the periodontal treatment. As in case I, clinical photographs at the front side and occlusal plane views were taken after fabricating clear aligner on the cast and applying the device (Figs. 19 and 20). Figs. 21 and 22 are clinical photographs of the front side and occlusal plane views after 3 weeks of using the new appliance. A new appliance was applied again after 6 weeks (Figs. 23 and 24). Prosthodontic treatment was performed as planned (Figs. 25 and 26). After completing prosthodontic treatment, radiographs were taken for radiographic evaluation (Fig. 27).

Figure 17.

Pre-periodontal treatment (clinical photograph at the front side view).

Figure 18.

Pre-periodontal treatment (clinical photograph at the occlusal plane).

Figure 19.

Appliance implementation (clinical photograph of the front side).

Figure 20.

Appliance implementation (clinical photograph of the occlusal plane).

Figure 21.

Three weeks after initial visit (clinical photograph of the front side).

Figure 22.

Three weeks after initial visit (clinical photograph of the occlusal plane).

Figure 23.

Six weeks after initial visit (clinical photograph of the front side).

Figure 24.

Six weeks after initial visit (clinical photograph of the occlusal plane).

Figure 25.

After prosthetic treatment (clinical photograph of the front side).

Figure 26.

After prosthetic treatment (clinical photograph of the occlusal plane).

Figure 27.

Post-treatment. Radiography. BC: horizontal distance from bone crest, BD: the most apical point of the bone defect, TD: vertical distance between the horizontal projection of the bone crest on the root surface, TD-BD: vertical dimension, BC-TD: horizontal dimension.

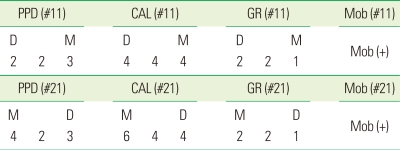

To measure the results of the treatment, PPD, CAL, GR, and mobility were measured after treatment. GR and CAL decreased about 1 mm compared to the first visit, and mobility decreased slightly (Table 7).

Table 7.

Post-treatment. Clinical examination of #21.

PPD: probing pocket depth, CAL: clinical attachment level, GR: gingival recession, Mob: mobility, M: mesial, D: distal.

In radiographs, the vertical and horizontal dimensions were measured after treatment (Table 8). Radiographically, the size of infrabony defects decreased 2.1 mm vertically and 0.7 mm horizontally. However, as in case I, actual bone filling in the lesions could not be determined based on the radiographic view alone.

Table 8.

Post-treatment. Radiographic measurements of #21.

BC: horizontal distance from bone crest, BD: the most apical point of the bone defect, TD: vertical distance between the horizontal projection of the bone crest on the root surface, TD-BD: vertical dimension, BC-TD: horizontal dimension.

Case III

The third patient was a 54-year-old male who visited our department June 11, 2009, with the chief complaint of anterior teeth sloping. Though clinical examination was performed as mentioned above (Table 9), no radiological examination was done due to the absence of the appearance of an infrabony defect (Fig. 28). He was diagnosed with chronic periodontitis localized on the 13-23 area and pathologic tooth migration. The treatment plan consisted of endodontic treatment, followed by periodontal therapy and tooth movement of 11 and 21, and prosthodontic treatment.

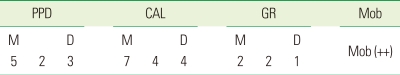

Table 9.

Clinical examination of #11, 21 at first visit.

PPD: probing pocket depth, CAL: clinical attachment level, GR: gingival recession, Mob: mobility, M: mesial, D: distal.

Figure 28.

Radiographic examination at first visit.

After periodontal treatment was performed (Figs. 29 and 30), an appliance was inserted (Figs. 31 and 32). Clinical photographs of the front side and occlusal plane were taken 6 weeks after appliance insertion (Figs. 33 and 34). Though prosthodontic treatment was recommended to the patient, the retention appliance was used. That's because the patient wanted to finish in the current state (Fig. 35). GR and CAL decreased about 1 mm compared to the first visit and there was no change in mobility (Table 10).

Figure 29.

Pre-periodontal treatment (clinical photograph of the front side).

Figure 30.

Pre-periodontal treatment (clinical photograph of the occlusal plane).

Figure 31.

Three weeks after initial visit (clinical photograph of the front side).

Figure 32.

Three weeks after initial visit (clinical photograph of the occlusal plane).

Figure 33.

Six weeks after initial visit (clinical photograph of the front side).

Figure 34.

Six weeks after initial visit (clinical photograph of the occlusal plane).

Figure 35.

Retention.

Table 10.

Post-treatment. Clinical examination of #11, 21

PPD: probing pocket depth, CAL: clinical attachment level, GR: gingival recession, Mob: mobility, D: distal, M: mesial.

DISCUSSION

Many previous studies have been conducted on the combination of periodontal and orthodontic treatments for PTM in the maxillary anterior area. According to Melsen et al. [13] in 1989, the combination of treatments could induce the generation of new attachment tissue and clinical attachment gain if patients can maintain reasonable oral hygiene. In 2002, Re et al. [14] reported that periodontal patients with an infrabony pocket could decrease their bony lesions through orthodontic tooth movement. Corrente et al. [12] wrote in their 2003 article that rearrangement of extruded teeth with infrabony defects provided a significant decrease in probing depth, clinical attachment gain, and bone filling, which was identified in radiographic views. Previous research has already confirmed a decrease of PPD and clinical attachment gain. Decreases in the horizontal and vertical size of infrabony defects were also shown on radiographies, though actual bone filling has not been confirmed.

Retention should also be considered after the orthodontic treatment of periodontal patients. The final location of the teeth is determined by a balance of forces among the lips, cheeks, tongue, and periodontal ligament [15]. Periodontal patients whose periodontal tissue has been destroyed by strong soft tissue forces, therefore permanently disrupting the balance of forces, may therefore need permanent retention. The best retainer for those patients is flexible spiral wire [16]. In 1982, Nyman et al. [17] reported that splinting with a retainer had a positive effect on the attachment of connective tissue and bone regeneration.

In summary, to treat cases of PTM in the maxillary anterior area using a clear aligner, the first step is to determine the pathologic causes. If the condition stems from periodontal problems, general periodontal therapy should be performed. If the movement happens spontaneously, which is uncommon, the periodontal treatment has to be wrapped, and minimum tooth migration is done using a clear aligner. Permanent retention should follow.

A clear aligner is effective on partial movement of the teeth and it is reasonable, therefore, to expect decreases in probing pocket depth, gingival recession, clinical attachment gain, mobility, and esthetic recovery as a result of its use.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Chasens AI. Periodontal disease, pathologic tooth migration and adult orthodontics. N Y J Dent. 1979;49:40–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martinez-Canut P, Carrasquer A, Magán R, Lorca A. A study on factors associated with pathologic tooth migration. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24:492–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunsvold MA. Pathologic tooth migration. J Periodontol. 2005;76:859–866. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.6.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sutton PR, Graze HR. The blood-vessel thrust theory of tooth eruption and migration. Med Hypotheses. 1985;18:289–295. doi: 10.1016/0306-9877(85)90030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Remensnyder O. A gum-massaging appliance in the treatment of pyorrhea. Dent Cosmos. 1926;28:381–384. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kesling HD. The philosophy of the tooth positioning appliance. Am J Orthod Oral Surg. 1945;31:297–304. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim TW. Principle and clinical application of clear aligner. Seoul: Myungmun Publishing Co; 2005. pp. 60–76. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim TW. Principle and clinical application of clear aligner. Seoul: Myungmun Publishing Co; 2005. pp. 18–47. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ericsson I, Thilander B, Lindhe J. Periodontal conditions after orthodontic tooth movements in the dog. Angle Orthod. 1978;48:210–218. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1978)048<0210:PCAOTM>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wennström JL, Stokland BL, Nyman S, Thilander B. Periodontal tissue response to orthodontic movement of teeth with infrabony pockets. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1993;103:313–319. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(93)70011-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindhe J, Karring T, Lang NP. Clinical periodontology and implant dentistry. 4th ed. Oxford: Blackwell; 2003. pp. 752–754. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corrente G, Abundo R, Re S, Cardaropoli D, Cardaropoli G. Orthodontic movement into infrabony defects in patients with advanced periodontal disease: a clinical and radiological study. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1104–1109. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.8.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Melsen B, Agerbaek N, Markenstam G. Intrusion of incisors in adult patients with marginal bone loss. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1989;96:232–241. doi: 10.1016/0889-5406(89)90460-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Re S, Corrente G, Abundo R, Cardaropoli D. Orthodontic movement into bone defects augmented with bovine bone mineral and fibrin sealer: a reentry case report. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2002;22:138–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Proffit WR. Equilibrium theory revisited: factors influencing position of the teeth. Angle Orthod. 1978;48:175–186. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1978)048<0175:ETRFIP>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dahl EH, Zachrisson BU. Long-term experience with direct-bonded lingual retainers. J Clin Orthod. 1991;25:619–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nyman S, Karring T, Bergenholtz G. Bone regeneration in alveolar bone dehiscences produced by jiggling forces. J Periodontal Res. 1982;17:316–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1982.tb01159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]