Abstract

Background:

In pemphigus, autoantibodies are directed against adhesion molecules, which make the junctions between keratinocytes, and thus determining their level can reflect the disease activity.

Aim:

The purpose of this study is to determine the clinical significance of the autoantibody levels in pemphigus management.

Materials and Methods:

The clinical features of 47 pemphigus vulgaris patients were assessed and patients′ sera were investigated by indirect immunofluorescence using monkey esophagus as a substrate for autoantibody levels.

Results:

We found a significant correlation between antibody titers and mucosal severity scores. Initial antibody titers of the patients with at least one mucosal lesion at the end of the first month of the therapy were found significantly higher than the patients who had no mucosal lesion. With the therapy, lesions resolved earlier than the antibody titers.

Conclusion:

In patients with pemphigus, especially in cases who were not treated before, sera antibody levels are a valuable tool in evaluating disease severity and choosing initial treatment. In patients who had been taking any systemic treatment, it is difficult to make a relationship between antibody levels and disease severity, because therapy improves disease earlier than the antibody titers. However, estimating antibody levels can be helpful for clinicians in disease management, in reducing or ceasing treatment dosage and anticipating recurrence.

Keywords: Indirect immunofluorescence, disease severity, autoantibody, pemphigus, therapy response

Introduction

Pemphigus is a group of chronic autoimmune blistering diseases of the skin and mucous membranes. Despite the possibility of many side effects, a high dosage of systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents are used for a long time in its management. Because of the recurrence probability, ceasing therapy must be thought when a long period of clinical remission is achieved. Monitoring of the disease activity with clinical or immunological parameters may help the clinician in its management. In pemphigus, researches are directed toward serum autoantibodies against adhesion molecules, which make the junctions between keratinocytes, and determining the value of these antibodies in reflecting the disease activity.

Indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) has been used to detect serum autoantibodies for the diagnosis of pemphigus and to evaluate the disease activity, since 1967. Patients′ sera are incubated with an epithelial substrate, and any bound antibody is detected by the subsequent addition of fluorescein-labeled antiglobulin sera and then examined with the help of fluorescence microscopy. In this way, serum autoantibodies can be detected. But this technique can give false negative results in patients with early localized disease and those in remission, and it can give false positive results in many conditions.[1,2]

Assessing serum autoantibody levels in patients with pemphigus can be a useful tool in evaluating the disease activity. Autoantibody titers can be a good indicator in choosing initial appropriate treatment and evaluating the response to therapy. Autoantibody titers can also be helpful to clinician in predicting prognosis, planning corticosteroid tapering schemata, terminating the therapy, and anticipating disease exacerbations. Circulating intercellular antibody titers often parallel the disease activity; however, there is no detailed prospective study. Whether an increase in antibody titers is a marker of an inevitable disease deterioration or stopping the treatment is safe in a patient whose antibodies cannot be detected is still not answered.

In this study we assessed the autoantibody levels in relation to disease severity and response to therapy in patients with pemphigus, for the purpose of determining its value as an immunological parameter which can helf in the management of this disease.

Materials and Methods

The clinical features of 47 patients with pemphigus vulgaris were assessed. The diagnosis was made on the basis of clinical, histological, and immunopathological criteria. We collected serum from these patients at the beginning of the study and during follow-up. Patients′ sera were investigated by indirect immunofluorescence using monkey esophagus as a substrate for autoantibody levels.

Disease severity score

Oral mucosa, skin, and general severity scores were assessed initially and on monthly examinations.

Oral mucosa score: It was classified according to the dissemination of lesions in the oral mucosa:

0. There was no lesion in the oral mucosa.

1. Minimal: there were limited lesions in only one mucosal region, like buccal, labiogingival, lingual, palatal, or pharyngeal.

2. Moderate: two mucosal regions were affected.

3. Severe: minimum three mucosal regions were affected.

Skin score: It was classified according to the dissemination of skin lesions:

1. Minimal: less than or equal to 10% of body surface area was affected.

2. Moderate: 11-30% of the body surface area was affected.

3. Severe: more than 30% of the body surface area was affected.

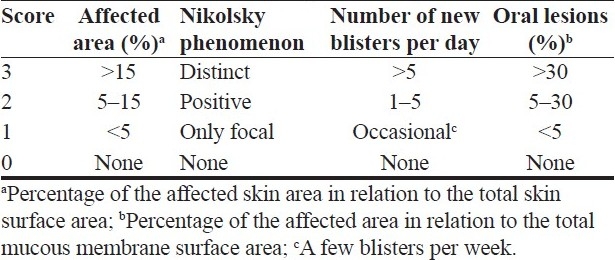

General score: It was examined according to the revised severity index for pemphigus which was produced in 2000[3] [Table 1]. The total of the scores for each item gives the severity index: total score <5 mild, 5–7 moderate, >7 severe. Total score was evaluated as the numerical value for the statistical analysis.

Table 1.

Pemphigus severity index

Antibody titer

Patients’ sera samples with serial dilutions were investigated by indirect immunofluorescence using monkey esophagus as an epithelial substrate for autoantibody levels. Sera samples were incubated with monkey esophagus, and fluorescein-labeled antiglobulin sera were added subsequently. Each serum sample was examined under fluorescence microscopy by the same person. The procedure was initiated with 1/20 dilution of sera. When fluorescence was found on 1/20 or more than 1/20 titers, the serum was admitted as positive. Antibody titers were evaluated as a numerical value and they were recorded at the beginning of the study and monthly thereafter and their relationship with disease severity was examined.

Blood type

We examined patients’ blood types because we use monkey esophagus as an epithelial substrate in IIF analysis and there may be possible common antigens between human and monkey tissues which can affect the antibody titer.

Statistical analysis was performed using nonparametric tests with P < 0.05 indicating a significant result. The Mann-Whitney U-test and Kruskal-Wallis test were used to estimate the differences between the antibody titers of the patients. Spearman's rho test was used to correlate disease severity and autoantibody titers. We estimated the difference between the first 3 months of antibody titers which were examined monthly, by multiple comparisons′ test. The chi-square Fisher's exact test was used to estimate the differences between the recurrence rates of the patients whose antibody titers decreased and whose antibody titers did not. All calculations were performed with SPSS 10 for Windows.

Results

Forty-seven patients were studied. Their initial antibody titer was between 0 and 1:1280, and the median titer was 1:160. The sensitivity of IIF was 100% in patients who had only mucosal involvement. The sensitivity of IIF was 85.7% (30:35) in patients who had mucocutaneous lesions. Overall, the sensitivity of IIF was 89% (42:47). Five patients′ initial antibody titers were quantified as negative. Three of them had been treated for pemphigus, and two of them had never been treated for pemphigus previously. The sensitivity was 92.5% (25:2) in patients who had never been treated for pemphigus previously, and it was 85% (17:20) in patients who had been treated for pemphigus.

There was no significant correlation between the initial antibody titer and duration of lesions (P > 0.05). There was no significant difference between the initial antibody titers of patients with mucosal and mucocutaneous involvement (P > 0.05).

We found a significant correlation between initial antibody titers and initial mucosal scores (P<0.05), but there was no consistent relationship between initial antibody titers and skin severity and general severity scores (P > 0.05). Also, second and third antibody titers showed no significant relationship with concurrent mucosal, skin, and general severity scores (P > 0.05).

There was no significant correlation between initial antibody titers and general severity score which was examined at the end of the first month of treatment (P > 0.05). έnitial antibody titers of the patients, who had at least one mucosal lesion at the end of the first month of treatment, were found significantly higher than the patients who had no mucosal lesion (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference between initial antibody titers of the patients who had no skin lesion and patients who had at least one mucosal lesion at the end of the first month of treatment (P > 0.05).

Thirty-six patients were followed up monthly over a 1-year period. Twenty-one patients had recurred (58.3%). We found no significant difference between initial antibody titers of the patients who had recurred and patients who had not recurred (P > 0.05). There was no significant relationship between the severity of recurrence and the antibody titer level which was estimated just before the recurrence (P > 0.05).

Seventeen patients′ antibody titers could be estimated at the recurrence; 10 of them (58.8%) showed an elevation of the antibody titer concurrently. There was no significant relationship between the severity of mucosal, skin, and general severity scores of the recurrence and the antibody titers which was estimated concurrently (P > 0.05).

We found no significant difference between initial antibody titers and the antibody titers which were measured at the end of the first month of treatment (P > 0.05), but we found a significant difference between initial antibody titers and the antibody titers which were measured at the end of the second and third month of treatment (P < 0.01).

We found no significant difference between the recurrence rates of the groups whose antibody titers decreased twofolds and groups whose antibody titers did not (P > 0.05). There was also no significant difference between the recurrence rates of the groups whose antibody titers became negative and groups whose antibody titers did not (P > 0.05).

Blood type

There was no significant difference between antibody titers of the patients who were O blood type, A blood type, and B and AB blood types (P > 0.05). There was also no significant difference between antibody titers of the patients who were Rh positive and negative (P > 0.05).

Discussion

The hallmark of pemphigus is the finding of IgG autoantibodies against the desmosomes, the most prominent cell–cell adhesion junctions in stratified squamous epithelia. It is known that pemphigus vulgaris is characterized by autoantibodies against a 130 kDa transmembrane glycoprotein of desmosomes, called desmoglein 3 (Dsg3), and pemphigus foliaceus is characterized by autoantibodies against a 160 kDa transmembrane glycoprotein of desmosomes, called desmoglein 1 (Dsg1), although patients with generalized pemphigus vulgaris who have mucocutaneous lesions usually have both anti-desmoglein 3 and anti-desmoglein 1 antibodies.[4] As shown in previous studies, 33-46% of patients with pemphigus vulgaris did not have the same pemphigus vulgaris phenotype (mucosal or mucocutaneous) which was determined with autoantibodies profile.[5,6] The different results between the studies might be due to the subjective assessment of subtyping of pemphigus to mucosal, cutaneous, and mucocutaneous forms, and to the change of cutaneous or mucosal involvement by time. Also, the autoantibody profile might be misleading, because the anti-desmoglein 3 and anti-desmoglein 1 antibodies might become negative in serum species obtained during remission. Therefore, analyzing the serum species from untreated cases or patients with active disease active disease may be recommended.

The severity of pemphigus in relationship with serum autoantibody levels has been examined in many studies. The data have been conflicting. Although early studies suggested that pemphigus antibody levels which were measured by IIF were a useful marker of disease activity,[7–12] later studies with analyzing serial titers concluded that pemphigus antibody titers did not always correlate well with disease severity and IIF titers were not consistent enough to be used as a guide to therapy or prognosis or monitoring the disease activity.[12–16] In most of these studies, mucosal and cutaneous disease severities were not graded seperately and only one epithelial substrate was used for IIF which is probably not sufficiently sensitive to detect changes in both Dsg1 and Dsg3 antibody levels.[17,18] There were declared cases; some of them had positive antibody titers without any lesion. Although some patients had negative antibody titers with widespread lesions.

IIF titers vary according to both the epithelial substrate used and the relative quantities of Dsg1 and Dsg3 antibodies in the test serum;[17] thus making correlations with disease severity is complex, particularly when examining those pemphigus vulgaris sera that contain both Dsg1 and Dsg3 antibodies.

The optimum substrate for IIF has yet not been established. No substrate is universally sensitive. However, when pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus were considered seperately and grouped according to the presence of either Dsg1 and/or Dsg3 autoantibodies in the serum, it had been shown that human skin was a more sensitive substrate in subjects with pemphigus foliaceus, in whom only Dsg1 autoantibodies were detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and, on average, IIF titers were 4.8 doubling dilutions higher than on monkey esophagus. In contrast, monkey esophagus was a more sensitive substrate in patients with mucosal pemphigus vulgaris, in whom the sera contained Dsg3 autoantibodies only and titers were, on average, 4.4 times higher than on human skin.[17] Monkey esophagus also tended to be more sensitive in the patients with mucocutaneous pemphigus vulgaris with both Dsg3 and Dsg1 autoantibodies, although titer differences on the two substrates tended to be smaller (1.8 doubling dilutions on average).[17] In another study, monkey esophagus was found to be superior or equal to human skin as a substrate for IIF in both pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus.[19] The reason for the discrepancy between these results is unknown. Possibilities include a racial difference in the way the antibodies in the serum react to the substrates, or perhaps the site from which the normal skin is taken may influence the IIF titers and hence the sensitivity of the technique.[19] Dsg expression can be changed according to the site from which the skin is taken; this can explain the contradictory results between the studies. Moreover, there may be differences between humans in antigen expression in both the skin and the other substrates. IIF is a subjective technique and it depends on the experience of the person who investigates. So it is important that all of the serum samples in a study must be investigated by the same person.

Titers on each substrate are likely to depend on the relative quantities of Dsg1 and Dsg3 antibodies, and it is conceivable that some pemphigus vulgaris sera might show higher titers on human skin, if Dsg1 autoantibodies were more abundant than Dsg3.[17] In the light of these findings, it is conceivable that discrepancies in the relationship between IIF titers and pemphigus disease severity described in previous studies[12,14,15] could be at least partially explained. IIF studies using human skin may not be adequately sensitive to detect changes in the Dsg3 antibody level and thus may not correlate well with oral disease severity and, likewise, some mucosal substrates may not be adequately sensitive to detect changes in the Dsg1 autoantibody levels. If skin and oral disease were scored separately and compared with IIF titers on human skin and monkey esophagus, respectively, it is possible that better correlations would be seen and therefore IIF titers would be of more use clinically.

It was demonstrated that in pemphigus independent to its subtype, skin disease severity relates to Dsg1 antibody levels and oral severity relates to Dsg3 antibody levels.[20] A relationship neither between Dsg1 antibodies and oral severity nor between Dsg3 antibodies and skin severity could be described,[20] although mild skin involvement can be seen in patients with Dsg3 antibodies alone. We used monkey esophagus, which contains dense Dsg3, as a substrate in our study. Thus we found a significant relationship between mucosal severity and antibody titers. We did not find a relationship between antibody titers and skin severity and also general severity scores. However, we were unable to demonstrate a significant relationship between antibody titers and any severity score at second and third months of the treatment. It is probably due to the treatments′ effect which depresses disease activity earlier than the antibody levels.

In previous studies, it was shown that the diagnostic sensitivity of IIF in pemphigus, independent to its subtype, was 83% in human skin and 90% in monkey esophagus.[17] When data from studies of IIF on both human skin and monkey esophagus were combined, the diagnostic sensitivity of IIF was increased to 100%.[17] In our study, the diagnostic sensitivity of IIF on monkey esophagus was 89% (42:47). Five patients′ autoantibody titers were examined to be negative, and all of them had mucocutaneous lesions; three of them were on treatment for pemphigus when their serum samples were taken. We showed that the diagnostic sensitivity of IIF on monkey esophagus was 100% in patients with mucosal pemphigus vulgaris.

It is difficult to make a relationship between antibody levels and disease severity in patients who take any systemic therapy. Treatment with high dosage or pulse corticosteroids usually reverses bullae rapidly, but antibody titers doesn’t decrease at the same rate. So clinical improvement occurs earlier than the reduction in antibody titers in most of patients, especially in patients who have elevated antibody levels. It is thought that the treatment might have supressed pathogenic mechanisms triggered by antibody binding; thus cases whose disease improves with treatment but antibody levels remain elevated can be seen.[20] In our study, we showed that the disease severity improved clearly with the first month of the treatment, but the antibody levels decreased after the 2 months of therapy. In a study which was performed by Judd and Lever, it was found that IIF was negative in 41% of patients with lesions and receiving treatment, and it was positive in 45% of patients free of lesions.[14] Moreover, seven patients without lesions and without treatment for more than a year had a positive titer.[14] In our study, we examined that IIF was negative in 15% of patients with active lesions and receiving treatment. IIF was negative in 7.5% of patients who had never been treated for pemphigus previously. We found a positive antibody titer at a 1:80 level on the serum of a patient who had no active lesion and had no treatment for at least 2 months. Her systemic corticosteroid and azathioprine therapy was ceased 2 months ago; her antibody titer was 1:80 at her two follow-ups which were made at 2-month intervals and we found no relapse at her 1-year follow-up.

In pemphigus, although there is a possibility for developing many side effects to a high dosage prolonged systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents, ceasing therapy must be considered when a long period of clinical remission is achieved. This decision is made according to the clinical course, but if immunofluorescence findings are negative, it can be presumed that the recurrence risk is reduced. It was shown that the recurrence risk was 13-27% if DIF was negative, 44-100% if DIF was positive, 24% if IIF was negative, and 57% if IIF was positive.[21,22]

In a study,[21] DIF and IIF were performed on 24 pemphigus vulgaris patients who were in a state of clinical remission and on maintenance therapy with oral prednisone. During a follow-up period of 20 months, 1 of 8 patients with negative DIF relapsed compared with 2 of 6 patients with weak positive DIF and 5 of 10 patients with strong DIF. A total of 4 of 7 patients with positive IIF, who also showed positive DIF, relapsed compared with 4 of 17 with negative IIF. It is suggested that repeated immunofluorescence tests in pemphigus patients, who are in clinical remission, may serve as an indicator for the immunological activity and be of help in the management of these cases and in predicting recurrences. In some IIF-positive patients who had no apparent cutaneous and oral involvement, localized lesions in other mucosal membranes, especially in oesohagus, were detected.[23] However, IIF stand-alone has not been found reliable in determining the disease state.

Despite the overall relationship between Dsg1 antibodies and skin severity and between Dsg3 antibodies and oral severity, it was shown that there was a wide range of values within each severity score.[20] While Dsg1 and Dsg3 ELISA method might not detect all of the cell surface antibodies which were involved in the pathogenesis of the pemphigus, the IIF method might detect the antibodies which developed against various nonpathogenic antigens in normal epithelium. Patients with quiescent or mild disease but high antibody titers and also patients with severe disease but low antibody titers were described. It is possible that this may partially reflect the retrospective nature of some of the clinical data, which relied on the accuracy of the case notes. Also, IgG subclass may be an important determinant of pathogenicity. The total amount of anti-Dsg IgG autoantibodies was estimated in studies; because of this, it is possible that cases with minimal disease but high Dsg antibody levels may have a high proportion of nonpathogenic antibodies, either by virtue of their subclass or perhaps because they bind to epitopes that do not result in disease triggering.[20,24] In addition, there is evidence that pemphigus sera target multiple epitopes on both Dsg1 and Dsg3 molecules.[25] In patients with low ELISA values but active disease, it is possible that the serum contained pathogenic antibodies to nondesmoglein molecules or to epitopes on the intracellular domain of Dsg1 or Dsg3, which would be undetectable by the ELISA. Although there is a correlation between antibody titers and disease severity, in future, estimating the pathogenic antibody titers (IgG4) may be more informative and predictive.

In conclusion, in patients with pemphigus, especially in cases who were not treated before, serum autoantibody levels, when they are estimated with appropriate technique, are a valuable tool in evaluating disease severity and choosing initial appropriate treatment. In our study, we found a statistically significant correlation between mucosal severity and antibody titers which were estimated on monkey esophagus as a substrate in IIF. In patients who are taking any systemic treatment, it is difficult to make a relationship between antibody levels and disease severity because therapy improves disease earlier than decreasing antibody titers. However, estimating antibody levels can be helpful for a clinician in disease management, in reducing or ceasing treatment dosage and anticipating recurrence.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, editors. Andrews’ Diseases of the skin. Canada: Saunders Elsevier; 2006. Chronic Blistering Dermatoses; pp. 459–78. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandsen R, Frusic-Zlotkin M, Lyubimov H, Yunes F, Michel B, Tamir A, et al. Circulating pemphigus IgG in families of patients with pemphigus: Comparison of indirect immunofluorescence, direct immunofluorescence, and immunoblotting. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:44–52. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70324-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ikeda S, Imamura S, Hashimoto I, Morioka S, Sakuma M, Ogawa H. History of the establishment and revision of diagnostic criteria, severity index and therapeutic guidelines for pemphigus in Japan. Arh Dermatol Res. 2003;295:12–6. doi: 10.1007/s00403-002-0367-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amagai M, Tsunoda K, Zillikens D, Nagai T, Nishikawa T. The clinical phenotype of pemphigus is defined by the antidesmoglein autoantibody profile. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:167–70. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70183-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jamora MJ, Jiao D, Bystryn J-C. Antibodies to desmoglein 1 and 3, and the clinical phenotype of pemphigus vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:976–77. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zagorodniuk I, Weltfriend S, Shtruminger L, Sprecher E, Kogan O, Pollack S, et al. A comparison of anti-desmoglein antibodies and indirect immunofluorescence in the serodiagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris. Int J Dermatology. 2005;44:541–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beutner EH, Jordon RE, Chorzelski TP. The immunopathology of pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid. J Invest Dermatol. 1968;51:63–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sams WM, Jordan RE. Correlation of pemphigoid and pemphigus antibody titres with activity of disease. Br J Dermatol. 1971;84:7–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1971.tb14190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chorzelski TP, Von Weiss JF, Lever WF. Clinical significance of autoantibodies in pemphigus. Arch Dermatol. 1966;93:570–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Loughlin S, Goldman GC, Provost TT. Fate of pemphigus antibody following successful therapy.Preliminary evaluation of pemphigus antibody determinations to regulate therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1769–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beutner EH, Chorzelski TP, Jablonska S. Immunofluorescence tests.Clinical significance of sera and skin in bullous diseases. Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:405–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1985.tb05807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Judd KP, Mescon H. Comparison of different epithelial substrates useful for indirect immunofluorescence testing of sera from patients with active pemphigus. J Invest Dermatol. 1979;72:314–16. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12531752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitzpatrick RE, Newcomer VD. The correlation of disease activity and antibody titres in pemphigus. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:285–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Judd KP, Lever WF. Correlation of antibodies in skin and serum with disease severity in pemphigus. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:428–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Creswell SN, Black MM, Bhogal BS, Skeete MVH. Correlation of circulating intercellular antibody titres in pemphigus with disease activity. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1981;6:477–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1981.tb02338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Acosta E, Gilkes JJ, Ivanyi L. Relationship between the serum autoantibody titres and the clinical activity of pemphigus vulgaris. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1985;60:611–4. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(85)90363-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harman KE, Gratian MJ, Bhogal BS, Challacombe SJ, Black MM. The use of two substrates to improve the sensitivity of indirect immunofluorescence in the diagnosis of pemphigus. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:1135–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiao D, Bystryn JC. Sensitivity of indirect immunofluorescence, substrate specificity, and immunoblotting in the diagnosis of pemphigus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:211–6. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)80127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patricia PL Ng, Steven TG Thng, Khatija Mohamed, Suat Hoon Tan. Comparison of desmoglein ELISA and indirect immunofluorescence using two substrates (monkey esophagus and normal human skin) in the diagnosis of pemphigus. Aus J Dermat. 2005;46:239–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2005.00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harman KE, Seed PT, Gration MJ, Bhogal BS, Challacombe SJ, Black MM. The severity of cutaneous and oral pemphigus is related to desmoglein 1 and 3 antibody levels. Bri J Derm. 2001;144:775–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.David M, Weissman-Katzenelson V, Ben-Chetrit A, Hazaz B, Ingber A, Sandbank M. The usefulmess of immunofluorescent tests in pemphigus patients in clinical remission. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120:391–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1989.tb04165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ratnam KV, Pang BK. Pemphigus in remission: value of negative direct immunofluorescence in management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:547–50. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jarzabek-Chorzelska M, Strasz-Kolacinska Z, Sulej J, Jablonska S. The use of two substrates for indirect immunofluorescence in the diagnosis of pemphigus. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:169–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhol K, Mohimen A, Ahmed AR. Correlation of subclasses of IgG with disease activity in pemphigus vulgaris. Dermatology. 1994;189:85–9. doi: 10.1159/000246938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kowalczyk AP, Anderson JE, Borgwardt JE, Hashimoto T, Stanley JR, Green KJ. Pemphigus sera recognize conformationally sensitive epitopes in the amino-terminal region of desmoglein-1 (Dsg1) J Invest Dermatol. 1995;105:147–52. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12316680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]