Abstract

Pilomatricoma (PMC) is a relatively uncommon benign skin neoplasm arising from the skin adnexa. Since the first description of PMC in 1880, there has been a gradual increase in understanding of the morphologic features and clinical presentation of this tumor. However, difficulties still persist in making clinical and cytologic diagnosis. We report the clinical and histopathological findings of two cases of pilomatricoma. In case 1, a 10-year-old girl presented with a right upper back mass. In case 2, a nine-year-old girl presented with a left ear lobe mass. The clinical findings in both the cases were suggestive of epidermoid/dermoid cyst. However, subsequent histopathologic examination confirmed these cases as pilomatricoma. This report reveals that pilomatricoma is a frequently misdiagnosed entity in clinical practice. The purpose of this article is to create awareness among clinicians on the possibility of pilomatricoma as a cause of solitary skin nodules, especially those on the head, neck or upper extremities.

Keywords: Pilomatricoma, dermatopathology, skin nodules

Introduction

Pilomatrixoma, or calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe, was first described in 1880 by Malherbe and Chenantais.[1] They described it as a benign subcutaneous tumor arising from sebaceous glands. In 1922, Dubreuilh and Cazenave[2] described the unique histopathologic characteristics of this neoplasm, including islands of epithelial cells and shadow cells. In 1961, Forbis and Helwig[3] proposed the term pilomatrixoma, to describe the condition to avoid a connotation of malignancy and denote its origin from hair matrix cells. In 1977, the term was changed as pilomatricoma to be more correct etymologically.[4]

Reports of pilomatricoma are sparse in the literature. The purpose of this article is to illustrate the diagnostic pitfalls encountered in these cases and to review the literature with special emphasis on the diagnostic features and differentials in order to better familiarize the clinicians with this entity.

Case Reports

Case 1

A 10-year- old girl presented with a bluish red nodule located on the right upper back. The lesion had been present for approximately 18 months, It had gradually increased in size during the last one month. The patient complained of occasional burning and pain. Physical examination revealed a firm, movable nodule measuring 3x2 cm in size. This mass had a nodular texture and was tender. The overlying skin showed bluish red discoloration. Family history was unremarkable. The initial clinical diagnosis was of sebaceous cyst. The nodule was excised and sent for histopathological examination.

Case 2

A nine-year- old girl presented with a nodular mass on the left ear lobe. The lesion was first noticed by the patient one month back; it had gradually increased in size during the last 15 days. Physical examination revealed a cystic nodule measuring 1×1 cm in size. The overlying skin showed red discoloration with prominent vessels. The patient gave a history of ear piercing few months back. Family history was unremarkable. Fine needle aspiration was done. Aspirate comprised of blood and cheesy material only. In view of the cystic consistency, cheesy aspirate and the previous history of ear piercing the clinical diagnosis of inclusion dermoid cyst was made. Nodule was excised and sent for histopathological examination.

Grossly, the specimen from case 1 was a hard, irregular mass measuring 2×1.3×1.0 cm. A gritty sensation was felt while cutting the specimen. The cut surface of the nodule was variegated in appearance. Specimen from Case 2 comprised of a few irregular grayish brown firm tissue pieces with bits of flaky material together measuring 1.5 ×1.0 cm.

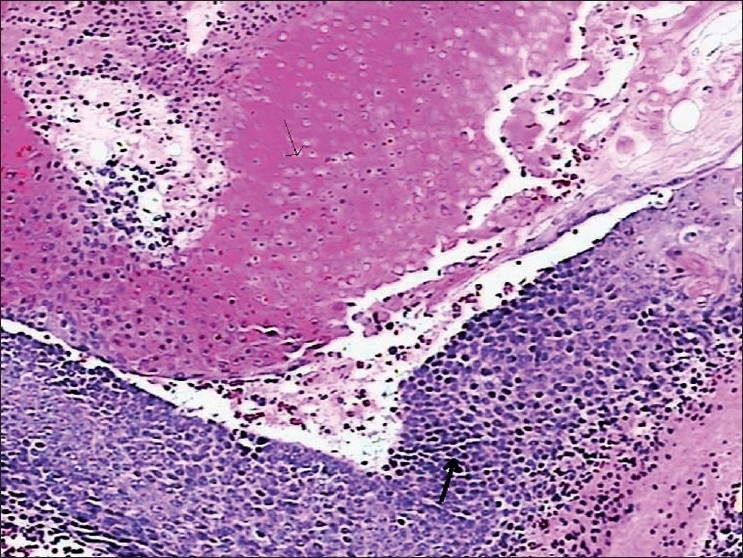

Histopathologically, the hematoxylin and eosin stained sections from both the specimens showed a tumor composed of an epithelial component exhibiting the typical population of basaloid and ghost cells [Figure 1] and a mesenchymal component showing fibroblastic proliferation. The basaloid cells were characterized by round to oval, hyperchromatic nuclei [Figure 1, thick arrow] and scanty cytoplasm. The ghost cells were eosinophilic with a central unstained shadow in the site of the lost nucleus [Figure 1, thin arrow]. In addition, in Case 1, a mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate with multinucleated giant cells, areas of calcification and metaplastic ossification were present. Based on these histopathological findings the masses were diagnosed as pilomatricoma.

Figure 1.

Photomicrograph of pilomatricoma showing the characteristic basaloid (thick arrow) and shadow cells (thin arrow) (H and E, ×100)

Discussion

Pilomatricoma is an asymptomatic slowly growing benign cutaneous tumor, differentiating towards the hair matrix of the hair follicle. It is covered by normal or hyperemic skin, and usually varies in size from 0.5 to 3 cm. It is found particularly on the head and neck region (over 50% of cases) with a female predominance.[5] Other locations include the upper extremity, trunk and lower extremity in decreasing order of frequency. No cases have been reported on the palms, soles or genital region.[6] Lymphadenopathy at the time of diagnosis has never been reported.

Though pilomatricoma can develop at any age, it demonstrates bimodal peak presentation during the first and sixth decades of life, however, 40% of cases occur in patients younger than 10 years of age and 60% of cases occur within the first two decades of life.[7]

Pilomatricomas usually are asymptomatic (pain appears only with associated inflammation and ulceration); deeply seated, firm, nontender subcutaneous masses adherent to the skin but not fixed to the underlying tissue. Stretching of the skin over the tumor shows the “tent sign” with multiple facets and angles, a pathognomonic sign for pilomatricoma.[8] In addition, pressing on one edge of the lesion causes the opposite edge to protrude from the skin like a “teeter- totter”. Both these “tent sign” and “teeter- totter sign” are the most helpful clinical clues to the diagnosis of pilomatricoma. Another characteristic feature of PMC is the blue red discoloration of the overlying skin which definitely excludes the possibility of epidermal inclusion or dermoid cyst. This characteristic clinical feature was overlooked in both these cases. Another feature overlooked in the first case was that the lesion was adherent to the skin but otherwise not fixed to the underlying tissues.

Despite the well described features, pilomatricomas, till date, are frequently misdiagnosed. Literature survey shows that the accuracy rate of the preoperative diagnosis of pilomatricoma ranges from 0% to 30%.[9] This may be attributable to the lack of familiarity with this tumor. Major factors contributing to misdiagnosis include: cystic lesions with varying consistency, punctum like appearance (due to skin tethering), atypical location and absence of clinically recognizable calcification. Another clinical dilemma encountered is the differentiation of this tumor from other benign masses, encountered in the clinical practice more frequently. These lesions include: epidermal inclusion cyst, dermoid cyst, brachial cleft remnants, preauricular sinuses, foreign body reaction, lipoma, degenerating fibroxanthoma, osteoma cutis, ossifying hematoma etc.[5]

To differentiate, inclusion cysts have a diffuse yellow color when filled with keratin and are softer and more palpable. They are rarely encountered in childhood.[10] In addition dermoid cysts are firmly attached to underlying tissue and show normal skin moving freely over the lesion. Neither exhibit irregular nodules on the skin whereas pilomatricoma does. Clinically, branchial cleft cysts present as a firm draining nodule.

Occasionally, there may be a history of previous trauma although this association is unusual. Finally pilomatricoma can be associated with other diseases such as myotonic dystrophy, Gardner syndrome, Steinert's disease, Turner syndrome and sarcoidosis.[11]

Radiologic imaging is of little diagnostic value for pilomatricoma. Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) may be helpful. However, the results of FNAC can be misleading if there are no ghost cells present in the aspirate attributing to the misdiagnosis of many cases.[12]

Histopathologically, pilomatricoma consists of lobules and nests of epithelial cells composed of two major cell types: basophilic cells and eosinophilic shadow cells. Early lesions show a predominance of basophilic cells grouped in islands at the tumor periphery. With tumor maturation, the basophilic cells acquire more cytoplasm and gradually lose their nuclei to become eosinophilic shadow cells. These latter cells constitute the central portion of the tumor and frequently calcify. Gradually this calcified foci increase imparting the bony hard consistency to the lesion.

Four distinct morphological stages of pilomatricoma are defined as: (a) early: small and cystic lesions, (b) fully developed: large and cystic, (c) early regressive: foci of basaloid cells, shadow cells and lymphocytic infiltrate with multinucleated giant cells, (d) late regressive: numerous shadow cells, absence of basaloid and inflammatory cells, calcification and ossification may be present. Based on these criteria both our cases fit in the early regressive stage.

Since spontaneous regression is never observed and malignant transformation is rare, the standard treatment of pilomatricoma is complete surgical excision. Recurrence after surgery is rare, with an incidence of 0% to 3%.[13] Malignant transformation to a pilomatrix carcinoma should be suspected in cases with repeated local recurrences.[13]

Conclusion

In conclusion, although there have been case reports in the literature describing the clinical features and addressing the main differential diagnoses and diagnostic pitfalls of pilomatricoma, this lesion continues to cause difficulty in clinical diagnosis. The main purpose of this article is to raise awareness among clinicians and illustrate the value of careful clinical screening, which can render definitive diagnosis of early, asymptomatic and clinically unsuspected cases of pilomatricoma.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Malherbe A, Chenanatis J. Note sur I’epithelioma calcifiedes glandes sebacees. Prog Med. 1880;8:826–37. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubreuilh W, Cazenave E. De I’ epithelioma calcifie: etude histolgique. Ann Dermatol Syphilol. 1922;3:257–68. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forbis R, Jr, Helwig EB. Pilomatrixoma (calcifying epithelioma) Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:606–17. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1961.01580100070009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnold HL. Pilomatricoma. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:1303. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yencha MW. Head and neck pilomatricoma in the pediatric age group: a retrospective study and literature review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2001;57:123–8. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(00)00449-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyd AS, Martin RW 3rd. Pathologic quiz case 1. Pilomatricoma (calcified epithelioma of Malherbe) with secondary ossification. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118:212–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moehlenbeck FW. Pilomatrixoma (calcifying epithelioma). A statistical study. Arch Dermatol. 1973;108:532–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham JL, Merwin CF. The tent sign of pilomatricoma. Cutis. 1978;22:577–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Julian CG, Bowers PW. A clinical review of 209 pilomatricomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:191–5. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orlando RG, Rogers GL, Bremer DL. Pilomatricoma in a pediatric hospital. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983;101:1209–10. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1983.01040020211008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barberio E, Nino M, Dente V, Delfino M. Guess what! Multiple pilomatricomas and Steiner disease. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:293–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agarwal RP, Handler SD, Matthews MR, Carpentieri D. Pilomatrixoma of the head and neck in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:510–515. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2001.117371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goufman DB, Murrell GL, Watkins DV. Pathology forum. Quiz case 2. Pilomatricoma (calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe) Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:218–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]