Abstract

Motivation: Mathematical modelling is central to systems and synthetic biology. Using simulations to calculate statistics or to explore parameter space is a common means for analysing these models and can be computationally intensive. However, in many cases, the simulations are easily parallelizable. Graphics processing units (GPUs) are capable of efficiently running highly parallel programs and outperform CPUs in terms of raw computing power. Despite their computational advantages, their adoption by the systems biology community is relatively slow, since differences in hardware architecture between GPUs and CPUs complicate the porting of existing code.

Results: We present a Python package, cuda-sim, that provides highly parallelized algorithms for the repeated simulation of biochemical network models on NVIDIA CUDA GPUs. Algorithms are implemented for the three popular types of model formalisms: the LSODA algorithm for ODE integration, the Euler–Maruyama algorithm for SDE simulation and the Gillespie algorithm for MJP simulation. No knowledge of GPU computing is required from the user. Models can be specified in SBML format or provided as CUDA code. For running a large number of simulations in parallel, up to 360-fold decrease in simulation runtime is attained when compared to single CPU implementations.

Availability: http://cuda-sim.sourceforge.net/

Contact: christopher.barnes@imperial.ac.uk; m.stumpf@imperial.ac.uk

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

Mathematical modelling is an integral part of systems and synthetic biology. Ordinary differential equations (ODEs) are the most commonly used methodology, but due to increasing appreciation of the importance of stochasticity in biological processes, stochastic differential equations (SDEs) and Markov jump processes (MJPs) are also applied. Since most models are non-linear, they generally cannot be solved analytically and therefore require numerical treatment. Furthermore, in order to understand behaviour across high-dimensional parameter space or to perform simulation based inference (Liepe et al., 2010; Toni et al., 2009), a very large number of simulations is required, making analysis of even the simplest models extremely time consuming.

For computationally expensive calculations, graphics processing units (GPUs) can be used. GPUs are many core, multi-threaded chips that are capable of several hundred GFLOPS (Kirk and Hwu, 2010). In terms of raw computing power, a single GPU in a desktop PC is comparable to a CPU cluster, but is much cheaper. However, due to their single instruction multiple data (SIMD) architecture, only highly parallelized processes can be efficiently run on GPUs. Even though platforms for general purpose GPU computing like CUDA® (Compute Unified Device Architecture) from NVIDIA® which provides a CUDA API exist, it remains difficult and time consuming to port existing algorithms that were designed for execution on CPUs. There have been developments in porting biochemical network simulators to GPUs (reviewed in Dematté and Prandi, 2010) but there does not currently exist a general purpose simulation tool that integrates multiple algorithms within the same interface.

Here, we present a new Python package called cuda-sim which provides highly parallelized algorithms for large scale simulations of biochemical network models. It is compatible with all NVIDIA GPUs that support CUDA. Absolutely no knowledge of CUDA and GPU computing is needed for the user to access the simulation algorithms: (1) The integration of ODEs is carried out using a GPU implementation of LSODA (Hindmarsh, 1983), (2) SDE simulations are provided via the Euler-Maruyama algorithm (Kloeden and Platen, 1999) and (3) simulations from a MJP (or Master equation) are performed using the Gillespie algorithm (Gillespie, 1976). All functionality can be accessed via a Python interface that hides the implementation details.

2 IMPLEMENTATION

The cuda-sim package is implemented in Python using PyCUDA (Klöckner et al., 2009) to access the GPU. PyCUDA acts as a wrapper for the CUDA API and provides abstractions that facilitate programming. As an additional layer between code and hardware, PyCUDA can also accommodate future changes in GPU architecture and will help ensuring that cuda-sim remains compatible with newer GPU generations. The package is written in an object oriented manner with an abstract simulator base class such that there is a common interface for accessing the algorithms.

Two different pseudo random number generators (RNG) are used for the SDE and MJP simulations. In the MJP simulations, each thread carries out different numbers of simulation steps and therefore needs different numbers of random numbers that are provided by one Mersenne Twister RNG (Matsumoto and Nishimura, 1998) per thread. In the completely parallel SDE simulations, each thread requires the same number of random numbers at the same time. This fact is exploited by a binary linear operations RNG that is local to a group of threads known as a warp (Thomas et al., 2009).

The user accesses the package by specifying SBML models which are parsed in cuda-sim using libSBML (Bornstein et al., 2008) and then converted to CUDA code modules. These code modules are automatically incorporated into the GPU kernels and run from within cuda-sim. Using a provided Python script, the user can specify model parameters and run the simulations with cuda-sim. Alternatively, the algorithms can be called directly from Python, allowing incorporation into other software projects.

It is advisable to use dedicated general purpose GPUs like the Tesla C2050 that we used for our timing studies. GPUs that provide graphical output have a time limitation on the execution length of programs and therefore will not be compatible with larger simulations run with cuda-sim.

3 TIMING COMPARISONS

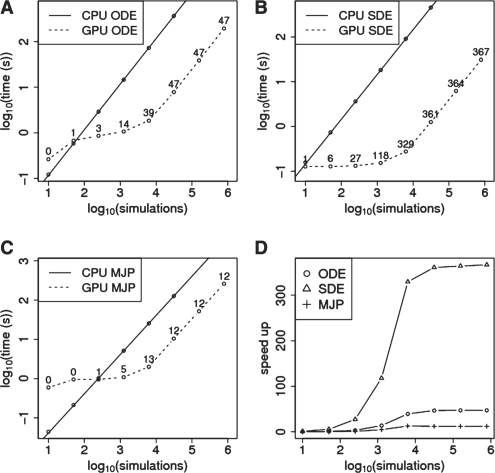

Using a model of p53-Mdm2 oscillations which contains 3 species, 6 reactions and 8 parameters (Geva-Zatorsky et al., 2006 and Supplementary Fig. S1) we simulated different numbers of time series of length 100 h and performed timing studies comparing the runtime on the GPU and the runtime on a single CPU (Fig. 1). For the ODE integrations to yield different results for each thread, instead of using fixed parameters, we drew parameters from uniform random distributions in the interval between 0 and 2.

Fig. 1.

Timing comparisons. (A–C) Time taken to simulate a given number of realisations for a single core of an Intel Core i7-975 Extreme Edition Processor 3.33 GHz (solid line) and one Tesla C2050 GPU (dashed line) for (A) the LSODA (B) the Euler–Maruyama and (C) the Gillespie algorithm, respectively. The relative speed-ups for given numbers of simulations are indicated next to the GPU simulation results. (D) Summary of the relative speed-up of the three different algorithms.

The CPU versions of the Gillespie and Euler–Maruyama algorithms were written in C++ and compiled with GCC using the -O3 optimization flag. For the LSODA algorithm comparisons, the CPU implementation in the SciPy Python module was used. The testing was done on an Intel Core i7-975 Extreme Edition Processor 3.33 GHz machine with 12 GB of RAM and one Tesla C2050 GPU. All points are averages over three runs. Since the CPU runtimes scale linearly, the total CPU time for large numbers of simulations can be extrapolated using a linear model.

For the LSODA, the Euler–Maruyama and the Gillespie algorithm, speed-ups of 47-fold, 367-fold and 12-fold are attained, respectively, for large numbers of simulations. Only for small numbers of simulations, are the CPU implementations of the three algorithms faster than the GPU versions (Fig. 1 A–C). This is due to the fact that the initialization on the GPU takes substantially longer than on the CPU. But since in most applications of these algorithms, either in order to explore the parameter space or to perform inference, at least thousands of simulations will be needed for which the GPU outperforms the CPU even for the rather simple p53-Mdm2 model.

We also compared the cuda-sim implementations of the LSODA and Gillespie algorithms with implementations in the Matlab package SBTOOLBOX2 (Schmidt and Jirstand, 2006) and our Euler–Maruyama implementation with the native sde function within Matlab. Since stochastic simulation in SBTOOLBOX2 supports only mass-action models, we used a model of enzyme kinetics (Supplementary Fig. S2). We obtained similar timing to the p53-Mdm2 model when using our CPU implementations (Supplementary Fig. S3) and speed-ups of between three and four orders of magnitude when compared to Matlab (Supplementary Fig. S4).

4 CONCLUSIONS

GPUs offer a powerful and cost-effective solution for parallel computing. cuda-sim provides a Python interface for biochemical network simulations using ODEs, SDEs and MJPs on NVIDIA CUDA GPUs and significantly reduces computation time. The package can be used as a standalone tool, or incorporated into other Python packages.

Funding: BBSRC (to C.B. and M.P.H.S.); Wellcome Trust (to J.L.); DAAD and Imperial College London (to Y.Z.); Kwoks' Foundation of Sun Hung Kai Properties. Royal Society Wolfson Research Merit Award (to M.P.H.S.).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- Bornstein BJ, et al. LibSBML: an API Library for SBML. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:880–881. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dematté L, Prandi D. GPU computing for systems biology. Brief Bioinform. 2010;11:323–333. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbq006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geva-Zatorsky N, et al. Oscillations and variability in the p53 system. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2006;2 doi: 10.1038/msb4100068. 2006.0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie DT. A general method for numerically simulating the stochastic time evolution of coupled chemical reactions. J. Comput. Phy. 1976;22:403–434. [Google Scholar]

- Hindmarsh AC. ODEPACK, A Systematized Collection of ODE Solvers, Scientific Computing. In: Stepleman RS, et al., editors. IMACS Transactions on Scientific Computation. Vol. 1. North-Holland: Amsterdam; 1983. pp. 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk DB, Hwu WW. Programming Massively Parallel Processors. Burlington: Morgan Kaufmann; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Klöckner A, et al. PyCUDA: GPU run-time code generation for high-performance computing. 2009 arXiv:0911.3456. [Google Scholar]

- Kloeden PE, Platen E. Numerical Solution of Stochastic Differential Equations. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Liepe J, et al. ABC-SysBio–approximate Bayesian computation in Python with GPU support. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1797–1799. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M, Nishimura T. Mersenne twister: a 623-dimensionally equidistributed uniform pseudo-random number generator. ACM Trans. Model. Comput. Simul. 1998;8:3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt H, Jirstand M. Systems Biology Toolbox for MATLAB: a computational platform for research in systems biology. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:514–515. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D, et al. Proceeding of the ACM/SIGDA international symposium on Field programmable gate arrays. New York: ACM; 2009. A comparison of CPUs, GPUs, FPGAs and massively parallel processor arrays for random number generation. [Google Scholar]

- Toni T, et al. Approximate Bayesian computation scheme for parameter inference and model selection in dynamical systems. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2009;6:187–202. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2008.0172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.