Abstract

The aim of this study was to investigate the association of C-reactive protein (CRP) with the metabolic syndrome (MS) and its components, and their association with coronary artery disease (CAD) in African-Americans (AA) and European-Americans (EA). MS was defined using revised National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III criteria in 224 AA and 304 EA undergoing coronary angiography; CAD was defined as ≥50% stenosis in any segment or as a composite cardiovascular score (0–75). The relative frequency of MS and CAD was significantly higher among AA subjects with high (≥3 mg/L) vs. low (<3 mg/L) CRP levels (76% vs. 24%, P<0.001 for MS; 70% vs. 30%, P=0.001 for CAD). The composite score was higher in subjects with high (≥3 mg/L) vs. low (<3 mg/L) CRP levels in both AA (16.9 vs. 11.2, P=0.038) and EA (18.5 vs. 14.5, P=0.002). Further, in both ethnic groups the cardiovascular score was higher among subjects with MS, irrespective of CRP levels. Adjusting for other risk factors, multiple regression analysis demonstrated an association of MS, but not CRP, with CAD among EA, but not AA (r2=0.533, P<0.001). In conclusion, MS was independently associated with CAD in both EA and AA, whereas CRP did not add prognostic information beyond established cardiovascular risk factors in either ethnic group.

Keywords: CRP, Metabolic syndrome, Risk factors, Ethnicity

We have previously reported on the distribution of the metabolic syndrome (MS) components and their relation to coronary artery disease (CAD) in African-American and European-American subjects undergoing coronary angiography and noted a difference in the pattern of components between the 2 groups. 1 The purpose of this study was to investigate the potential role of C-reactive protein (CRP) in the assessment of CAD risk in 2 ethnic groups with varying frequency of MS components.

METHODS

Subjects were recruited from a patient population scheduled for diagnostic coronary arteriography either at Harlem Hospital Center in New York City or at the Mary Imogene Bassett Hospital in Cooperstown, NY. The study design and inclusion and exclusion criteria have been described previously. 1–3 Briefly, a total of 648 patients, self-identified as European-American (n=344), African-American (n=232) or Other (n=72) were enrolled. Of the 576 European American and African-American subjects, 48 subjects were excluded due to incomplete data. Exclusion criteria for this study included use of lipid lowering drugs. The present report is therefore based on the findings in 528 subjects (304 European-Americans, 224 African-Americans). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Harlem Hospital, the Mary Imogene Bassett Hospital, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, and University of California Davis, and informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Blood pressure was measured with a random-zero mercury sphygmomanometer. Fasting levels of triglycerides, total and HDL cholesterol and glucose were determined using standard enzymatic procedures, and LDL cholesterol levels were calculated. 4–7 High sensitivity CRP levels were measured as described. 8,9 Homeostasis model assessment – insulin resistance was calculated as described 10,11 We defined the MS using revised National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III criteria. 12

The coronary angiograms were read by 2 experienced readers blinded to patient identity, the clinical diagnosis, and laboratory results. The readers recorded the location and extent of luminal narrowing for 15 segments of the major coronary arteries. 13 In the present study, patients were classified as having CAD if a stenosis of ≥50% was found in at least one of the segments. Patients without CAD were defined as having <50% stenosis in all of the segments. Of the patients without CAD, the majority (80.5%) had <25% stenosis, and of the patients with CAD, 81% had >75% stenosis. A composite cardiovascular score (0–75) was calculated based on determination of presence of stenosis on a scale of 0–5 of the 15 predetermined coronary artery segments.

Analysis of data was done with SPSS statistical analysis software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Results were expressed as means ± SD. Triglyceride, insulin and homeostasis model assessment – insulin resistance levels and the cardiovascular score were logarithmically transformed to achieve normal distributions. Proportions were compared between groups using χ2 analysis, and Fisher exact test where appropriate. Group means were compared using Student’s t-test. CRP levels were dichotomized as high and low groups (CRP <3 vs. ≥3 mg/L) based on common practice from previous studies. 14,15 Age and gender adjusted Spearman partial correlation coefficients were calculated for CRP and MS components across ethnicity. General linear measurement (GLM) multivariate analyses for CRP groups and MS groups were used for cardiovascular composite score after adjustment for gender, and post hoc analyses were performed by Tukey’ honest significant difference test. Multiple linear regression analyses were applied to assess the association of CRP and MS components with the composite cardiovascular score, an integrated measure of the degree of stenosis of the 15 measured coronary artery segments. We compared effects of CRP and MS in African-Americans and European-Americans on CAD using regression models with interaction terms. All analyses were 2-tailed, and P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The clinical characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. For both African-Americans and European-Americans, subjects with high levels of CRP had significantly higher levels of BMI, systolic blood pressure, triglyceride, insulin, and homeostasis model assessment – insulin resistance compared to those with low levels of CRP. Among African-Americans, but not European-Americans, subjects with high levels of CRP had significantly higher levels of apolipoprotein B, and lower levels of HDL cholesterol and apolipoprotein A–I. The results were essentially identical when adjusting for gender.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of study population according to C-reactive protein concentrations.*

| Clinical characteristics | African-Americans (n=224) |

P-value | European-Americans (n=304) |

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRP<3mg/L | CRP≥3mg/L | CRP<3mg/L | CRP≥3mg/L | |||

| Men/Women | 51/33 | 75/65 | 120/41 | 75/68 | ||

| Smoker | 34 (41%) | 67 (48%) | NS | 30 (19%) | 43 (30%) | 0.017 |

| Postmenopausal | 22 (67%) | 42 (65%) | NS | 29 (71%) | 58 (85%) | NS |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.4±1.1 | 31.0±0.9 | 0.003 | 28.2±0.5 | 31.0±0.5 | <0.001 |

| Waist-hip ratio | 0.91±0.01 | 0.91±0.01 | NS | 0.95±0.01 | 0.98±0.01 | 0.005 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 124±3 | 132±2 | 0.024 | 124±1 | 128±2 | 0.035 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 77±2 | 80±2 | NS | 74±1 | 75±1 | NS |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 188±7 | 197±6 | NS | 195±3 | 203±3 | NS |

| Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dl) | 116±6 | 128±5 | NS | 123±3 | 126±3 | NS |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dl) | 52±3 | 44±2 | 0.038 | 41±1 | 41±1 | NS |

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) | 97 (73–130) | 109 (81–152) | NS | 140 (102–204) | 165 (116–231) | 0.012 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 126±8 | 117±7 | NS | 119±5 | 139±5 | 0.007 |

| Insulin (μU/ml) | 10.8 (7.2–17.0) | 15.8 (9.8–24.8) | 0.006 | 12.1 (7.9–20.6) | 16.8 (12.0–32.8) | <0.001 |

| HOMA-IR | 1.40 (1.00–2.30) | 2.00 (1.35–3.20) | 0.012 | 1.70 (1.10–2.90) | 2.20 (1.60–4.70) | <0.001 |

| ApoB (mg/dl) | 123±6 | 135±5 | NS | 134±3 | 141±3 | NS |

| ApoA-I (mg/dl) | 135±5 | 123±4 | NS | 123±2 | 121±2 | NS |

NS, not significant. Data are means ± SE, or for non-normally distributed variables as median (interquartile range). Group means were compared using Student’s t-test. Values for triglyceride, insulin and HOMA-IR were logarithmically transformed before analyses.

Adjusted for age and gender.

Spearman’s partial correlation coefficients between CRP levels and MS components adjusted for age and gender across ethnicity are shown in Table 2. For both African-Americans and European-Americans, CRP concentrations were positively correlated with triglyceride levels and with obesity as measured by waist circumference. Among African-Americans, but not European-Americans, CRP levels were negatively correlated with HDL cholesterol levels.

TABLE 2.

Spearman partial correlation coefficient between C-reactive protein and metabolic syndrome components across ethnicity.*

| Variable | African-Americans | P-value | European-Americans | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waist circumference (cm) | 0.349 | 0.001 | 0.274 | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 0.199 | NS | 0.019 | NS |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 0.105 | NS | 0.012 | NS |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dl) | −0.297 | 0.006 | −0.094 | NS |

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) | 0.218 | 0.045 | 0.114 | 0.048 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | −0.086 | NS | 0.065 | NS |

Adjusted for age and gender.

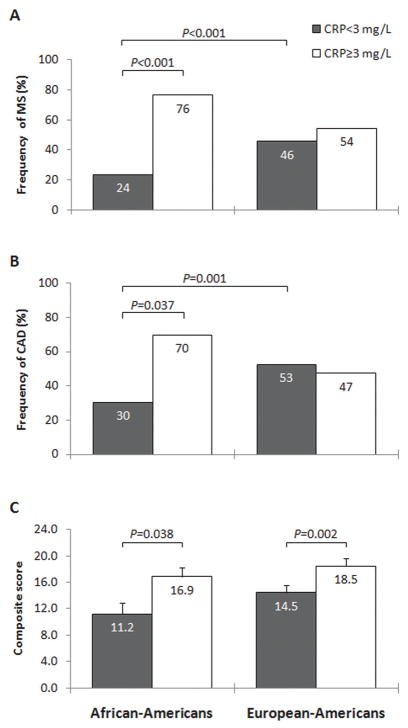

Next we analyzed the relative frequency of the MS, CAD and the composite cardiovascular score among subjects with low and high CRP levels (<3 vs. ≥3 mg/L). African-American subjects with high CRP levels had significantly higher frequency of the MS (76% vs. 24%, P<0.001, Figure 1A) and CAD (70% vs. 30%, P=0.037, Figure 1B) compared to those with low level of CRP. The gender adjusted composite score was higher among African-American subjects with high vs. low CRP levels (16.9 vs. 11.2, P=0.038, Figure 1C). Interestingly, European-American subjects with high CRP levels also had significantly higher gender adjusted composite score (18.5 vs. 14.5, P=0.002, Figure 1C), compared to those with low CRP levels. Among subjects with low CRP levels, African-Americans had significantly lower frequency of the MS (24% vs. 46%, χ2=14.1, P<0.001) and CAD (30% vs. 53%, χ2=9.6, P=0.001) compared to European-Americans (Figure 1A and 1B). Although the gender adjusted composite score was substantially lower among African-American compared to European-American subjects with low CRP levels (11.2±1.7 vs. 14.5±1.2) (Figure 1C), the difference did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 1.

Ethnicity-specific frequency of MS (A), frequency of CAD (B) in subjects with CRP levels greater than or less than 3.0 mg/L, and cardiovascular composite score (C) in subjects with CRP levels greater than or less than 3.0 mg/L. Proportions were compared between groups using χ2 analysis. P-values were calculated using General linear measurement (GLM) multivariate analyses for CRP groups after adjustment for gender, and post hoc analyses were performed by the Bonferroni test for two independent samples, and values for cardiovascular composite score were logarithmically transformed before analyses. The non-transformed values are shown in the graphs.

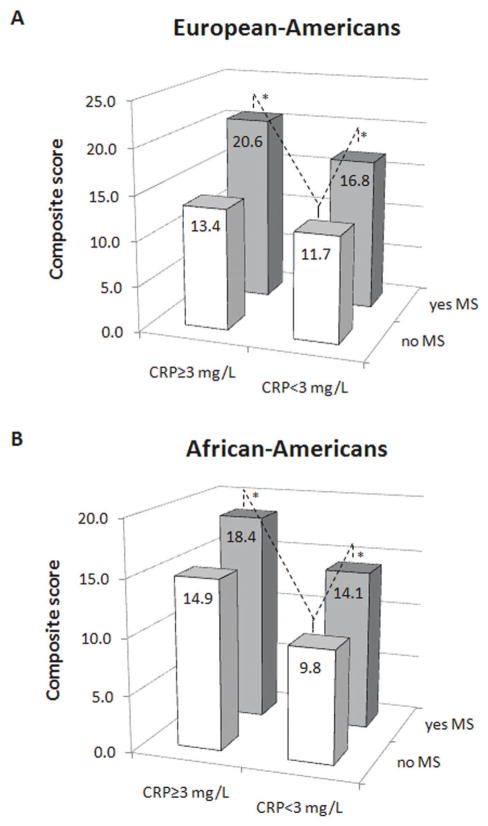

We then analyzed the combined association of inflammation and presence of the MS on the CAD magnitude in both groups, adjusting for gender. As seen in Figure 2A, among European-Americans, the cardiovascular score was significantly higher among subjects with the MS, irrespective of CRP group, compared to those without the MS and signs of inflammation (20.6 for high CRP, 16.8 for low CRP vs. 11.7, P<0.001 and P=0.014, respectively). Further, the composite cardiovascular score was similar in subjects with low vs. high CRP levels for subjects either with (16.8 vs. 20.6) or without (11.7 vs. 13.4) the MS (Figure 2A). Similar results were seen among African-Americans with a significant difference in the cardiovascular score among subjects with the MS, irrespective of CRP group, compared to those without the MS and signs of inflammation (18.4 for high CRP, 14.1 for low CRP vs. 9.8, P<0.001 and P=0.017, respectively) (Figure 2B). Taken together, these findings suggest that among both ethnic groups, presence of the MS to a higher degree than presence of high CRP levels constituted a risk factor for CAD.

Figure 2.

Cardiovascular composite score in European-Americans (A) and African-Americans (B) according to CRP levels greater than or less than 3.0 mg/L and according to the presence or absence of the MS. P-values were calculated using General linear measurement (GLM) multivariate analyses for CRP groups and MS groups after adjustment for gender, and post hoc analyses were performed by the Bonferroni test for two independent samples, and values for cardiovascular composite score were logarithmically transformed before analyses. The non-transformed values are shown in the graphs.

Finally, we performed multiple linear regression analysis to explore potential predictors of CAD as measured by the composite cardiovascular score. When MS and CRP were considered, only the MS components, but not CRP levels, were determinants of the cardiovascular score in European-Americans (r2=0.326, F=5.1, P<0.001). No significant associations were found for African-Americans. As we did not observe any significant association of MS with CAD in the later group, we performed an interaction test of MS in both ethnic groups using European-Americans without MS as a reference population. For both African-Americans and European-Americans, the presence of MS resulted in a significant increase in cardiovascular score (β =6.5; P<0.001). In African-Americans, the effect of MS on the cardiovascular score was less than in European-Americans, but the interethnic difference was not statistically significant (β =−1.2; NS). In the final regression models, when other established cardiovascular risk factors such as age, gender, smoking and LDL cholesterol were added to the model, the MS, age, gender, and smoking, but not CRP were associated with the cardiovascular score (r2=0.533, F=18.8, P<0.001). In African-Americans, significant associations were seen for age, smoking and LDL cholesterol, while the MS and CRP were not associated with the cardiovascular score in European-Americans (r2=0.430, F=8.1, P<0.001).

DISCUSSION

The main novel finding in our study was a role of CRP and MS as CAD risk factors in African-Americans and European-Americans. When only CRP and MS were considered, for both groups the MS was associated with a higher degree of cardiovascular disease irrespective of CRP levels. However, when other risk factors were taken into account, MS was independently associated with CAD in European-Americans but not in African-Americans, whereas CRP did not add prognostic information beyond established cardiovascular risk factors in both ethnic groups.

We have previously reported on the distribution of MS components and their relation to CAD in African-Americans and European-Americans. 1 In this study we investigated the potential role of CRP in the assessment of CAD risk in two ethnic groups with varying frequency of MS components. Inflammation plays a major role in the development of diabetes and is related to several components of the MS. Studies have shown that CRP levels correlate with individual components of MS such as elevated triglyceride levels, low HDL cholesterol, obesity, elevated blood pressure, and insulin resistance. 16,17 The relation with obesity is particularly well documented. 18 Our findings were also in agreement with previous studies as levels of CRP were strongly correlated with the obesity and lipid components of the MS in both European-Americans and African-Americans. As suggested by others, proinflammatory cytokines produced by adipose tissue (e.g. TNF-α and IL-6) might influence insulin resistance and glucose uptake,19,20 promote hepatic fatty acid synthesis, 21 and increase hepatic CRP production. 22

The study was cross sectional in nature. Subjects in our study were recruited from patients scheduled for coronary angiography and are likely more typical of a high-risk patient group than the healthy population at large. This may explain the relatively high levels of CRP among our subjects. However, none of the patients had a history of acute coronary symptoms or surgical intervention within 6 months, arguing against any secondary increase in inflammatory parameters due to an acute CAD. Further, clinical and laboratory parameters were in agreement with differences generally observed between healthy African-American and European-American populations from other studies.

Our finding has several clinically important implications. First, CRP did not add prognostic information beyond established cardiovascular risk factors in any of the ethnic groups. Second, a therapeutic targeting of the MS might be particularly important in reducing CAD risk, both in subjects with or without signs of inflammation. Although our findings need to be confirmed in larger population based studies they suggest that targeted individualized prevention strategies might be of value in the treatment of heterogeneous patient populations.

Acknowledgments

The project was supported by grants 49735 (Pearson, TA, PI) and 62705 (Berglund, L, PI) from National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. This work was supported in part by the UC Davis CTSC (RR 024146), and Dr. E. Anuurad is a recipient of an American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship (0725125Y).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Anuurad E, Chiem A, Pearson TA, Berglund L. Metabolic syndrome components in African-Americans and European-American patients and its relation to coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:830–834. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paultre F, Pearson TA, Weil HF, Tuck CH, Myerson M, Rubin J, Francis CK, Marx HF, Philbin EF, Reed RG, Berglund L. High levels of Lp(a) with a small apo(a) isoform are associated with coronary artery disease in African American and white men. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:2619–2624. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.12.2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anuurad E, Rubin J, Lu G, Pearson TA, Holleran S, Ramakrishnan R, Berglund L. Protective effect of apolipoprotein E2 on coronary artery disease in African Americans is mediated through lipoprotein cholesterol. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:2475–2481. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600288-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGowan MW, Artiss JD, Strandbergh DR, Zak B. A peroxidase-coupled method for the colorimetric determination of serum triglycerides. Clin Chem. 1983;29:538–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allain CC, Poon LS, Chan CS, Richmond W, Fu PC. Enzymatic determination of total serum cholesterol. Clin Chem. 1974;20:470–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warnick GR, Benderson J, Albers JJ. Dextran sulfate-Mg2+ precipitation procedure for quantitation of high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol. Clin Chem. 1982;28:1379–1388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macy EM, Hayes TE, Tracy RP. Variability in the measurement of C-reactive protein in healthy subjects: implications for reference intervals and epidemiological applications. Clin Chem. 1997;43:52–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ridker PM, Cushman M, Stampfer MJ, Tracy RP, Hennekens CH. Inflammation, aspirin, and the risk of cardiovascular disease in apparently healthy men. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:973–979. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704033361401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levy JC, Matthews DR, Hermans MP. Correct homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) evaluation uses the computer program. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:2191–2192. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.12.2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adler AI, Levy JC, Matthews DR, Stratton IM, Hines G, Holman RR. Insulin sensitivity at diagnosis of Type 2 diabetes is not associated with subsequent cardiovascular disease (UKPDS 67) Diabet Med. 2005;22:306–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, Gordon DJ, Krauss RM, Savage PJ, Smith SC, Jr, Spertus JA, Costa F. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–2752. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller M, Mead LA, Kwiterovich PO, Jr, Pearson TA. Dyslipidemias with desirable plasma total cholesterol levels and angiographically demonstrated coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1990;65:1–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90017-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ridker PM. Clinical application of C-reactive protein for cardiovascular disease detection and prevention. Circulation. 2003;107:363–369. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000053730.47739.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toss H, Lindahl B, Siegbahn A, Wallentin L. Prognostic influence of increased fibrinogen and C-reactive protein levels in unstable coronary artery disease. FRISC Study Group. Fragmin during Instability in Coronary Artery Disease. Circulation. 1997;96:4204–4210. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.12.4204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ridker PM, Buring JE, Cook NR, Rifai N. C-reactive protein, the metabolic syndrome, and risk of incident cardiovascular events: an 8-year follow-up of 14 719 initially healthy American women. Circulation. 2003;107:391–397. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000055014.62083.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Festa A, D’Agostino R, Jr, Howard G, Mykkanen L, Tracy RP, Haffner SM. Chronic subclinical inflammation as part of the insulin resistance syndrome: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study (IRAS) Circulation. 2000;102:42–47. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferrante AW., Jr Obesity-induced inflammation: a metabolic dialogue in the language of inflammation. J Intern Med. 2007;262:408–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hotamisligil GS, Budavari A, Murray D, Spiegelman BM. Reduced tyrosine kinase activity of the insulin receptor in obesity-diabetes. Central role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:1543–1549. doi: 10.1172/JCI117495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Youd JM, Rattigan S, Clark MG. Acute impairment of insulin-mediated capillary recruitment and glucose uptake in rat skeletal muscle in vivo by TNF-alpha. Diabetes. 2000;49:1904–1909. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.11.1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feingold KR, Grunfeld C. Role of cytokines in inducing hyperlipidemia. Diabetes. 1992;41 (Suppl 2):97–101. doi: 10.2337/diab.41.2.s97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kushner I. Regulation of the acute phase response by cytokines. Perspect Biol Med. 1993;36:611–622. doi: 10.1353/pbm.1993.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]